Texas Railroad History - Tower

81 - Houston (T&NO Jct.)

A Crossing of the Galveston, Harrisburg & San Antonio

Railway and the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe Railway

Above: John W.

Barriger III took this undated photo of Tower 81 facing north from the rear

platform of his private railcar. The photo undoubtedly dates from the 1933 -

1941 timeframe when Barriger served as the chief administrator for railroad

investments at the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. The photo is

from the International & Great Northern (I&GN) album in the John W. Barriger III National Railroad Library. Barriger's I&GN train is exercising

trackage rights on a branch line of the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe (GC&SF)

Railway. The rights belong to the I&GN's parent company, the New Orleans, Texas

& Mexico Railroad, a subsidiary of Missouri Pacific (MP). Barriger's train will proceed south to

Alvin, then take the GC&SF main line east to

Algoa where it will return to MP family rails for

the trip

south to the Rio Grande Valley. Barriger's car has just crossed Southern Pacific

(SP) tracks running east/west on the opposite side of the tower; this photo was

taken 80 to 90 years ago and the SP tracks had already been in place for

80 to 90 years! Note that the cattle guard directly in front of Barriger is duplicated on

the SP tracks at left; there were lots of

cows around! The two

semaphore signals in the distance mark the south end of

New South Yard through which Barriger's train has just passed. Barely

visible in front of those semaphores, a connecting track from the SP line comes

in from the left to enter the yard. North of the tower, the GC&SF tracks are leased to the Houston Belt & Terminal Railway all the way to Union Station

from which Barriger departed.

Below: Barriger's view is

vastly different today. (Google Street View, 2019)

The first railroad in Texas, the Buffalo Bayou, Brazos

and Colorado (BBB&C) Railway, began construction in 1851 at

Harrisburg, a small

port on Buffalo Bayou a few miles downstream from Houston.

The initial objective was to build west to the vicinity of the Colorado River,

and

the first track segment, twenty miles to Stafford's Point

(now the Houston suburb of Stafford), was completed in 1853. By the start of the Civil War, the tracks

had reached (but did not cross) the Colorado River near Columbus. The BBB&C

entered bankruptcy after the War, and in a judgment for non-payment, its

ownership was assigned to the contractor who built it, William Sledge.

In

1870, Sledge sold the BBB&C to a group led by Thomas W. Peirce (with the

unusual ei spelling.) Peirce was a wealthy Boston mercantile

businessman, lawyer and landowner (including a large sugar plantation near

Arcola.) He had done legal work for the BBB&C before the War, thus he was very

familiar with the railroad. Peirce spent a few years

rehabilitating the railroad and

improving its operations before resuming construction. The existing

BBB&C charter provided authority for the railroad to build along the Colorado

River from the vicinity of Columbus north and west to La Grange and

Austin, but Peirce preferred to continue building west to San Antonio.

He approached the Texas Legislature to ask them to modify the BBB&C

charter to allow him to build in that direction. He also requested an innocuous provision

to allow his

railroad to connect with any Pacific railroad. As the Legislature

amended the BBB&C's charter to grant the requested amendments, they also granted

one other request by Peirce: changing the railroad's name to the Galveston,

Harrisburg & San Antonio (GH&SA) Railway.

|

Left: The

Houston Evening Telegram of

September 9, 1870 reported that the "late Legislature" had changed the

name of the BBB&C to become the "Galveston, Harrisburg & San Antonio R.

R. Co.". The Legislature had acted earlier in the summer; the

Handbook of Texas claims July 27 as

the date. The article reports that the charter

amendment included "the right to extend a parallel line along the

Galveston road to that city." This authorized the GH&SA to lay tracks from Harrisburg to

Galveston, essentially parallel to the

existing Galveston, Houston & Henderson (GH&H) Railroad which had the

only line between Houston and Galveston. Despite this authorization, the

GH&SA never built its own line to Galveston, but eventually served it

using an acquired line. |

GH&SA construction reached San Antonio in 1877, a

couple of years after

Peirce had coined the well-known term Sunset Route to help advertise his

railroad's westward progress. Peirce completed a further extension from San

Antonio to El Paso in 1883 as part of an agreement

with Southern Pacific (SP) Chairman Collis P. Huntington, who was working to

establish a southern transcontinental rail line from California to New Orleans.

The GH&SA line provided SP with tracks from El Paso to Houston, and SP subsequently leased the GH&SA and then acquired it.

In 1875, about the time Peirce was building through

Luling

toward San Antonio, the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe (GC&SF) Railway was starting

construction on its bridge over Galveston Bay. The GC&SF had been chartered by

Galveston businessmen in 1873 to build a rail line west from Galveston that

would eventually turn toward the Texas Panhandle and proceed

to Denver, which had access to the Transcontinental Railroad through nearby

Cheyenne. This was deemed by the

organizers a superior alternative to access the west coast rather than building

from Galveston to San Diego. The basic idea was the same as SP's: bring west coast freight

to the Port of Galveston for shipping on Gulf and Atlantic waters. The GC&SF

also wanted their main line to avoid Houston; they accused Houston officials of

interfering with Galveston trade by periodically interdicting cargo on the GH&H

under the guise of yellow fever quarantines.

The GC&SF's construction was

slow, and much of 1879 was spent reorganizing the company's finances. By the

start of 1880, their main line out of Galveston had crossed the Brazos River

five miles west of Arcola and reached a connection

with Peirce's GH&SA at the new settlement of Rosenberg,

about sixteen miles beyond the river. Service was

inaugurated farther north in early 1880 to Wallis and

Sealy (in January), and Brenham

(in April.) The new year of 1880 also brought a nagging issue into focus for

the GC&SF: they needed to serve Houston. The decision to bypass to the south was rational in 1873, but only seven years later, the

GC&SF could no longer ignore Houston's growth. They negotiated rights to use the "Columbia Tap" route

of the International & Great Northern (I&GN) Railway into Houston from their common junction at Arcola, commencing August 1, 1880. In May, 1883, the GC&SF built

its own line into Houston. Construction departed the main line at the tiny

community of Alvin and proceeded to downtown Houston, running perfectly straight for 25 miles on a heading 15

degrees west of due north. Nineteen miles north of Alvin, the GC&SF tracks

crossed the GH&SA tracks at grade three miles west of Harrisburg. Two miles north of this

crossing, the GC&SF built South Yard to handle Houston area freight operations.

The new branch from Alvin enabled the GC&SF to relinquish its 1880 rights on

the Columbia Tap from Arcola; they were, in essence, following a script the GH&SA had

already written. The GH&SA had earlier obtained rights to

Houston on the Columbia Tap, from

Pierce Junction thirteen miles north of Arcola. In

1880, at SP's urging, Peirce built his own line into Houston from Stella, a

thousand feet west of

Pierce Junction, relinquishing his rights on the Columbia Tap. SP eventually

defined the Sunset Route main line as the route north at Stella which went to SP's yards north of Buffalo Bayou.

From there, the Sunset Route continued east to New Orleans on SP's Texas & New

Orleans (T&NO) Railroad. The former GH&SA main line from Stella to Harrisburg

became a branch line.

From Brenham, the GC&SF had expanded north to

Ft. Worth and Dallas in 1881 while continuing to

build to the northwest, reaching Brownwood in 1885. But GC&SF

management recognized a significant problem; they were almost entirely dependent on local

traffic. To utilize the strategic advantage of their main line to Galveston, they needed a partner to generate Port traffic. The obvious

suitor was the much larger Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe (AT&SF) Railway which did

not yet have a Texas presence and which needed a Gulf port for agriculture

exports from the high plains. The GC&SF's lengthy main line from Ft. Worth to

Galveston would mesh well with AT&SF's network farther north if the two

railroads could establish an appropriate interchange point. Negotiations led to

an 1886 agreement under which the AT&SF would acquire the GC&SF on favorable

terms. The acquisition proceeded as planned in 1887

and the GC&SF began operating as a wholly-owned subsidiary of the AT&SF.

The GH&SA / GC&SF crossing on the Alvin branch line may have seen steady traffic, but it was

certainly not a junction of two main lines. The GH&SA tracks had become a branch

line between Stella and Harrisburg. In earlier days, GH&SA

traffic bound for Galveston from the west would have passed through the crossing to

be exchanged with the GH&H at Harrisburg. Now it was more likely to take the shorter GC&SF

main line connection to Galveston from Rosenberg. For the

GC&SF, their new branch into Houston primarily served to compete with the GH&H,

except it was longer! Yet, Houston's continuing growth meant that railroad

development in Houston was never static, and the changes that were coming would

profoundly affect the traffic through the GH&SA / GC&SF crossing.

|

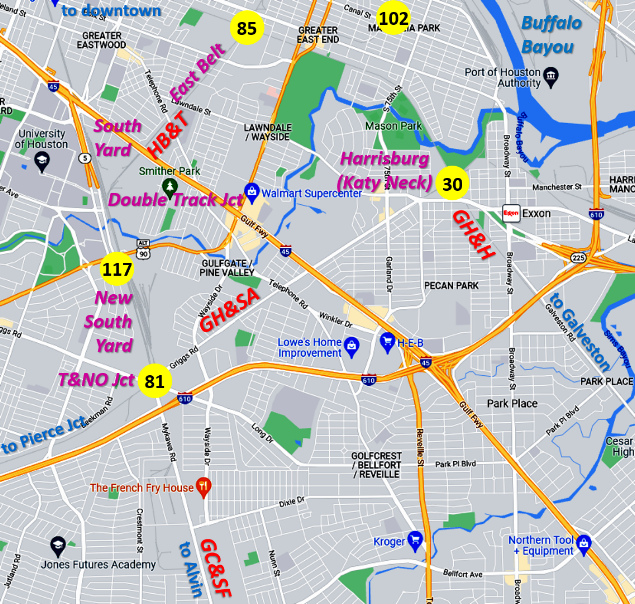

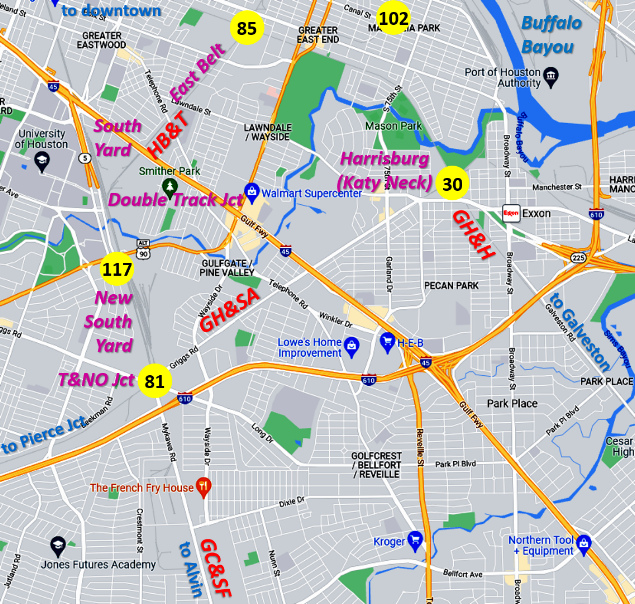

Left:

Historic designations (some of which are still in use!) have been

annotated onto a current Google Map of southeast Houston in the vicinity

of Tower 81. Tower 81 was authorized for

operation by the Railroad Commission of Texas (RCT) on February 25,

1910 to control the GH&SA/GC&SF crossing. RCT's list of active interlockers published at the end of the year

reported Tower 81 as a 12-function

mechanical plant at Harrisburg. The listing remained

unchanged until 1915

when the location became "Houston"; perhaps the city limits had reached

the vicinity. The function count increased to 16 in 1916 and to 17 in

1923, when the location was changed to "Houston (5 mi. S. W.)" In 1926,

RCT revised the date of authorized operation in 1910 to be May 7 instead

of February 25. Although

it became known as "T&NO

Junction" (and RCT descriptions sometimes incorporated such names), "T&NO

Junction" never appeared in RCT's lists because when SP merged the GH&SA into the T&NO in 1934,

RCT was no longer publishing an annual list of active interlockers. The

final one was

dated December 31, 1930.

Below: It's still

called T&NO JCT. (Google Street View, February, 2022)

|

In

1904, several years before the commissioning of Tower 81, the GC&SF joined with three other railroads (none of which yet served

Houston!) to charter the Houston Belt & Terminal (HB&T) Railway. The

four railroads shared ownership equally; the other three

were controlled by B. F. Yoakum, a native Texan who had risen from a

track gang on the I&GN to become Chairman

of the Board of Directors of the St. Louis San Francisco ("Frisco") Railway.

In 1905, he was additionally named Chairman of the Executive Committee of the

Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific ("Rock Island") Railroad, another major Midwest railroad.

Yoakum was considered a

marketing genius (pick up his

latest book on Amazon!), and he was very familiar with Texas railroading,

most recently as a Vice President of the GC&SF before moving to the Frisco in

1896.

Yoakum wanted to compete with SP for Gulf traffic using a coastal network

from New Orleans to Brownsville

centered on Houston. At Houston, Yoakum recognized that SP's rail network was not optimized to serve

the industrial base throughout the city. Multiple SP railroads shared a

passenger depot, but it was not favorably located, being north of Buffalo Bayou,

convenient neither to the heart of downtown nor the growing population base

south of the Bayou. Yoakum proposed to build a Union Passenger Station

downtown, south of Buffalo Bayou, and a belt railroad around Houston to facilitate industrial rail

service and interchange among the railroads.

The St. Louis, Brownsville & Mexico (SLB&M) Railway and the

Beaumont, Sour Lake & Western (BSL&W) Railway were two of Yoakum's three HB&T

railroads. Both were components of the Gulf Coast Lines (GCL), a collection of

railroads that Yoakum intended to weave into a coastal network that would

compete with SP. The other Yoakum railroad in

the HB&T was the Trinity & Brazos Valley (T&BV) Railroad, a company he had

hijacked -- strictly for its existing Texas railroad charter -- and redirected

with the help of the Colorado & Southern (C&S) Railroad (where Yoakum was a

Director.) The T&BV's role in Yoakum's scheme was to provide a bridge route

between his Frisco and Rock Island lines in Dallas and

Ft. Worth, and his GCL railroads in

Houston. Frisco and Rock Island traffic was being handed over to SP in north Texas

for movement to Houston, hence Yoakum needed his own route.

The HB&T's real purpose was to put track

and facility infrastructure into Houston so it could function as the central

hub of Yoakum's collective Gulf coast route structure. What was in it for the GC&SF? They only had the

branch line into Houston from Alvin, and, even with AT&SF backing, they had

limited opportunities in Houston; they were still a Galveston-focused railroad.

Joining with Yoakum at least gave them a chance to capture new traffic for

Galveston. And the GC&SF couldn't compete alone in the Houston market against

SP, which already controlled four railroads in

downtown Houston. There was a fifth SP railroad in

downtown Houston, but a lawsuit alleging unlawful acquisition had successfully

forced SP to divest it in 1904. The lawsuit had been filed by RCT in 1903,

mysteriously a full eleven years after the bankruptcy Receiver for the San Antonio &

Aransas Pass (SA&AP) Railway -- none other than B. F. Yoakum himself! -- had

approved SP's acquisition. SP blamed Yoakum.

The HB&T and more particularly, the SLB&M, eventually had a profound impact on traffic

through the GH&SA / GC&SF crossing, but it did not materialize as

quickly as expected. By 1906, the SLB&M had only built from

Brownsville to the tiny community of Algoa

on the GC&SF main line, still about 30 miles from Houston. Less than

five miles west of Algoa, the GC&SF branch at Alvin would give Yoakum

direct access to Houston, but no agreement to use

the Alvin line was forthcoming. The

GC&SF was driving a hard bargain, but Yoakum, a former GC&SF

executive, kept negotiating. His position was at odds with his financial backers

at the St. Louis Trust Co. whose management wanted him to forget the GC&SF

option and build eight miles farther north to Dickinson for a GH&H connection

into Houston. Newspaper articles repeatedly described behind-the-scenes intrigue

between Yoakum and his financiers, who wanted the immediate revenue

bonanza that would occur when single-train service became available between

Brownsville and Houston.

Yoakum had a much bigger goal in mind, so he was

adamantly opposed to extending the SLB&M tracks north from Algoa. A duplicate

route into Houston would damage his working relationship with the GC&SF. The HB&T was only a year into

existence and virtually all of its

asset base consisted of GC&SF tracks and infrastructure. More critically, Yoakum

needed to use the GC&SF branch from Alvin because it led directly into HB&T's new yard

under construction south of the GC&SF's South Yard (hence, it was

called New South Yard.)

Yoakum kept negotiating; the SLB&M tracks between Algoa and

Bay City were proving to have problematic drainage issues through the Brazos River bottom

lands, so he was in no position to start Brownsville -

Houston service anyway. A test train had reached Algoa from Brownsville in

March, 1906, but it took another 18 months to sort out the track problems. Scheduled service between Brownsville and Algoa commenced in

September, 1907, but with no agreement to use the Alvin branch, passengers had

to connect to GC&SF trains at Algoa to reach Houston.

|

When Yoakum was ready to deal, he made the deal. His agreement

with the GC&SF was dated April 1, 1908. It not only covered the SLB&M's

use of the Alvin branch (with scheduled single-train service between

Brownsville and Houston commencing April 19th), it also included the T&BV's use of the

Alvin branch and the GC&SF main line between Alvin

and Galveston.

If it was simply a bridge route

from Dallas and Ft. Worth to Houston, why did the T&BV need to serve Galveston?

In his grand scheme, Yoakum assigned Galveston service to the T&BV instead of

to a GCL railroad because the T&BV was half-owned by the C&S (the other

half-owner was the Rock Island, which Yoakum controlled.) Through its

subsidiaries, the C&S already had a direct route from Denver to

Fort Worth. With the

new GC&SF rights, the T&BV now had a direct route between Ft. Worth and Galveston,

albeit using GC&SF rails at both ends. (The T&BV's tracks from

Houston to Ft. Worth didn't go all the way; rights on

the GC&SF from Cleburne to Ft. Worth filled the gap.) Yoakum gave Galveston

service to the T&BV simply to enable the C&S to

offer single-train service between Denver and Galveston (with connections to

Brownsville at Algoa), service that no other railroad could claim to

provide.

While the SLB&M added traffic to the underutilized Alvin branch, it did

not impinge on the GC&SF. There was no industry and few passengers at

Algoa, and the SLB&M didn't stop elsewhere on GC&SF rails.

It is apparent that Yoakum's lengthy negotiations with the GC&SF pertained to his

plan for the C&S to offer single-train service between Denver and

Galveston. That service would be feasible only if the T&BV had rights to

serve passengers on the Ft. Worth - Galveston route, a critical market

for the GC&SF! That Yoakum ever reached an agreement with the GC&SF is testimony to his business savvy.

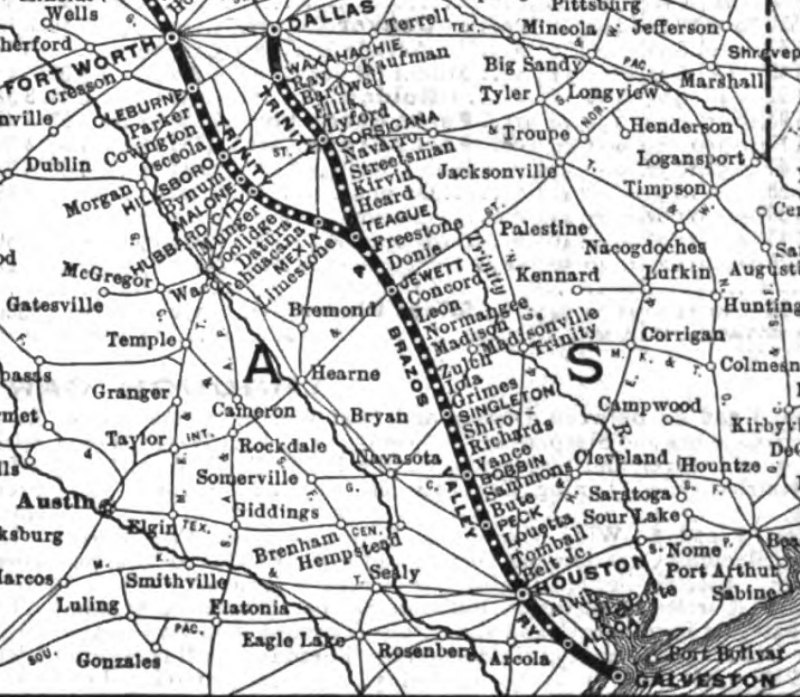

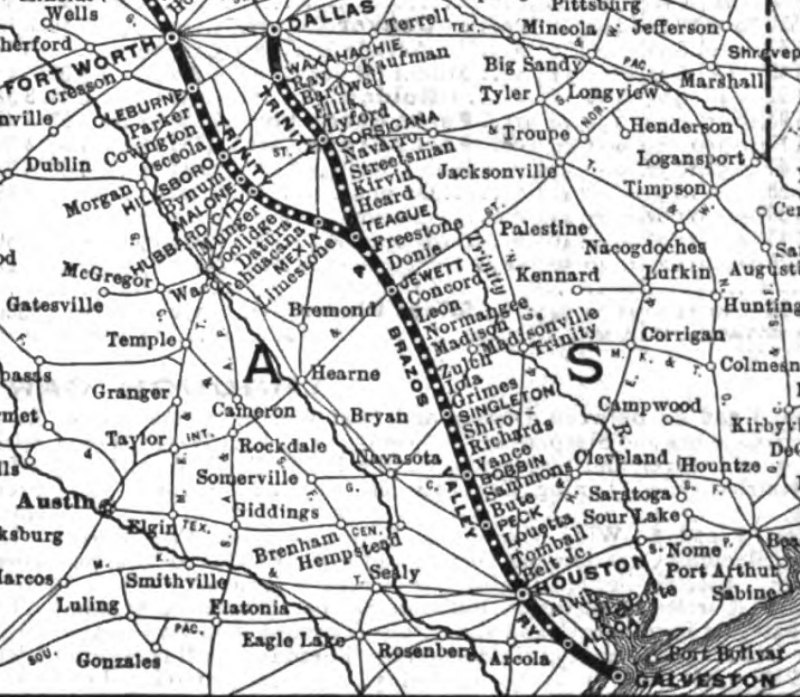

Left: This is the

bottom half of a C&S map

showing a direct line from Denver to Galveston via Ft. Worth taken from the

1908 Official Railway Guide. Between Cleburne and Algoa, the GC&SF's

competing route went to Morgan,

McGregor, Temple,

Cameron, Somerville,

Brenham, Sealy,

Rosenberg and

Arcola.

|

By late 1908, the HB&T, the SLB&M and the T&BV

had combined to increase

traffic through the GH&SA / GC&SF crossing. This may have helped justify

the Tower 81 interlocker, but realistically, HB&T had already committed to a

plan to interlock all of its crossings with other railroads (RCT would have

required it sooner or later.) The GC&SF's lease of tracks and infrastructure to

HB&T included the tracks north from the GH&SA crossing, so HB&T treated it as

just another of its many junctions. By the end of 1908, HB&T had already built

its first two interlocking towers, Towers 71 and 76,

companion towers governing two crossings of SP's Houston East & West Texas

Railroad on the north side of town. Soon thereafter, as HB&T's various belt

lines were extended and completed, HB&T opened Towers 81,

84, 85,

86 and 87 over the

span of twelve months beginning May, 1910. The planning for

Tower 80 (Belt Jct.) on the north side of Houston

had been initiated around the same time, or slightly before, Tower 81, but it's

commissioning date was delayed until July, 1913. The other two HB&T towers,

Tower 116 at Union Station and

Tower 117 at New South Yard, ended up being special

cases, hence the higher tower numbers, but they were always in HB&T's plans.

It didn't take long, less than a decade, for Yoakum's takeover and

redirection of the T&BV to prove to be financially improvident. It went into

bankruptcy in 1914 and emerged in 1930 as a newly organized company, the

Burlington - Rock Island (B-RI) Railroad, with ownership split equally

between Burlington, which had bought the C&S in 1908, and Rock Island. Ownership

of the B-RI ultimately fell to Burlington Northern (BN) when Rock Island went

bankrupt in 1980. BN merged with the AT&SF in 1995, creating Burlington

Northern Santa Fe (BNSF), which continues to operate the ex-T&BV main line

between Houston and Waxahachie. (The Teague -

Cleburne branch was abandoned in stages between 1932 and 1976.) AT&SF had owned the GC&SF since

1887, hence BNSF ended up as a half-owner of the HB&T through its inheritance of

the assets of the T&BV and the GC&SF.

Like the T&BV, the Frisco also entered

receivership, in 1913, creating havoc for the GCL which was controlled, but not owned, by the Frisco.

The GCL

railroads had various levels of ownership commonality through the St. Louis

Trust Co., but they were managed by Frisco executives as agents for

the syndicate. As the St. Louis Trust Co. was involved in the Frisco's

bankruptcy, the Court decided a reorganization was necessary so that a single

entity could own and operate all of the GCL railroads. A new parent company, the

New Orleans, Texas & Mexico (NOT&M) Railway, was incorporated in 1916 to

take over the GCL, and it proceeded to operate independently into the 1920s. In 1924,

the NOT&M bought the I&GN at the behest of Missouri Pacific (MP), whose attempt

to buy the I&GN earlier that year had been rejected by the Interstate Commerce

Commission (ICC). The ICC allowed the NOT&M to buy the I&GN in June, 1924,

and MP was then allowed to buy the NOT&M on January 1, 1925. Thus, MP acquired

its target I&GN along with all of the GCL railroads. This instantly gave MP half

ownership of the HB&T through the SLB&M

and the BSL&W, two of the component railroads of the GCL. MP was acquired by Union Pacific (UP) in 1982 and became fully

merged into UP in 1997. UP acquired SP in a 1996 merger. Several years later, UP

and BNSF agreed to dissolve the HB&T, divide its assets appropriately, and

operate in the Houston area through a mutual grant of reciprocal rights.

Above Left: Tower 81 in 1936, looking west on the

SP tracks (Greg Johnson collection)

Above Right:

a northbound caboose

passes Tower 81 in July, 1948

For crossings that existed prior to 1901, RCT rules

anticipated that when constructing an interlocking tower, an equal split of the

capital outlay would be levied among the railroads that benefitted from the

interlocker. One railroad would oversee the project, handling the procurement of

the interlocking plant and the design and construction of the tower (with

associated signals, derails, etc.) The other railroad(s) involved with the

crossing would then reimburse an appropriate share of the capital investment.

Once operational, the railroads typically would share the tower's recurring

operating and maintenance expenses (e.g. staffing, materials and utilities) on a

"weighted-function" basis, i.e. railroads paid by the ratio of the number of

interlocker functions dedicated to their rails compared to the interlocker's

total functionality. They could, however, make other agreements on cost-sharing.

In most cases, one railroad would staff the tower and handle all maintenance,

billing the other(s) periodically, a role that was almost inevitably assigned, at

least initially, to the railroad that built the tower.

Tower 81 was built

by SP, and the capital outlay would have been shared at least with the GC&SF,

and perhaps also with the HB&T which leased the GC&SF tracks north of the

crossing. It is essentially identical in appearance to numerous other SP towers (e.g. Tower 26,

Tower 21, Tower 16, among many others.) Prior

to 1959, Tower 81 was manned by SP employees dating all the way back to its

commissioning, as would be expected for the railroad that built the tower. On

January 1, 1959, SP and HB&T implemented an agreement they had signed on

November 18, 1958 to swap management of Tower 81 and

Tower 87. SP began staffing and maintaining Tower 87, which was located at

the eastern edge of SP's Englewood Yard north of Buffalo Bayou. HB&T

began staffing and maintaining Tower 81 at the south end of its New South Yard.

Four years later, HB&T issued 1963 Bulletin No. 1 which announced that Tower

81 would be closed on January 31, 1963, with the interlocker becoming remotely

controlled from Tower 117. At the time, Tower 81 was the only remaining HB&T

tower that had pipe-connected switches and derails controlled by mechanical

"armstrong levers" in the tower. All other HB&T towers had been modernized to

use power-assisted devices. An update to power-assisted functionality was

obviously overdue, so making the interlocker remote-controlled as a consequence

of the upgrade made sense and eliminated the recurring staffing expense. The

tower's closing was

approved by the ICC on June 23, 1962 from a formal request made by SP and HB&T

dated April 12, 1962. Tower 81 most likely remained intact only long enough for

the new equipment to be installed in trackside cabinets. The tower

structure's fate has not been determined, but historic aerial imagery suggests

that it had been removed by 1964.

Above Left: Looking north along the former GC&SF main line

into New South Yard from the Griggs Rd. grade crossing, the connecting track coming in from the left goes west to the

UP (ex-GH&SA) tracks on

which BNSF has rights. Old South Yard and New South Yard function as BNSF's main

yard in Houston (sometimes simply called "South Yard".) The UP/SP merger and the

BNSF merger resulted in mutual grants of trackage rights throughout the Houston area.

Traffic departing South Yard can take the connecting track to go west to

Rosenberg (Tower 17) to get on BNSF's main line to

Temple and beyond.

And as a consequence of MP's acquisition of the GCL railroads in 1925, UP

ultimately inherited the rights on the Alvin branch and portions of the GC&SF

main line that had been negotiated by B. F. Yoakum in 1908.

(Google Street View, Feb. 2022)

Above Right: This Google Earth

satellite image of the Tower 81 crossing shows the equipment cabinet at Control

Point T&NO JCT. The aforementioned connecting

track is prominent in the northwest quadrant. There are hardly any cars on the

roadways; everyone knows to avoid the numerous grade crossings in this area!

A live camera monitoring train traffic at the Tower 81

crossing can be found at

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XJRnxHb4AgU