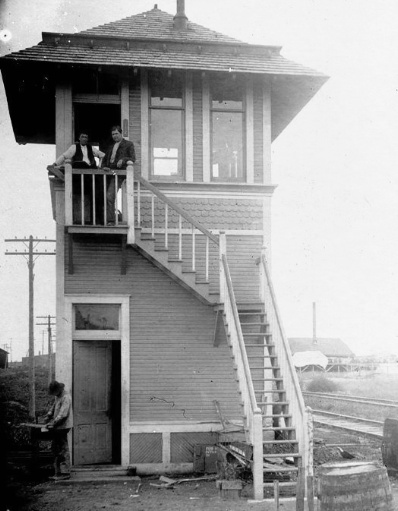

Among towers for which photos have not yet been found, this photo's history and the tower's appearance fits well with the limited details known about Tower 43, but it's only a guess until a verified photo of Tower 43 is located.

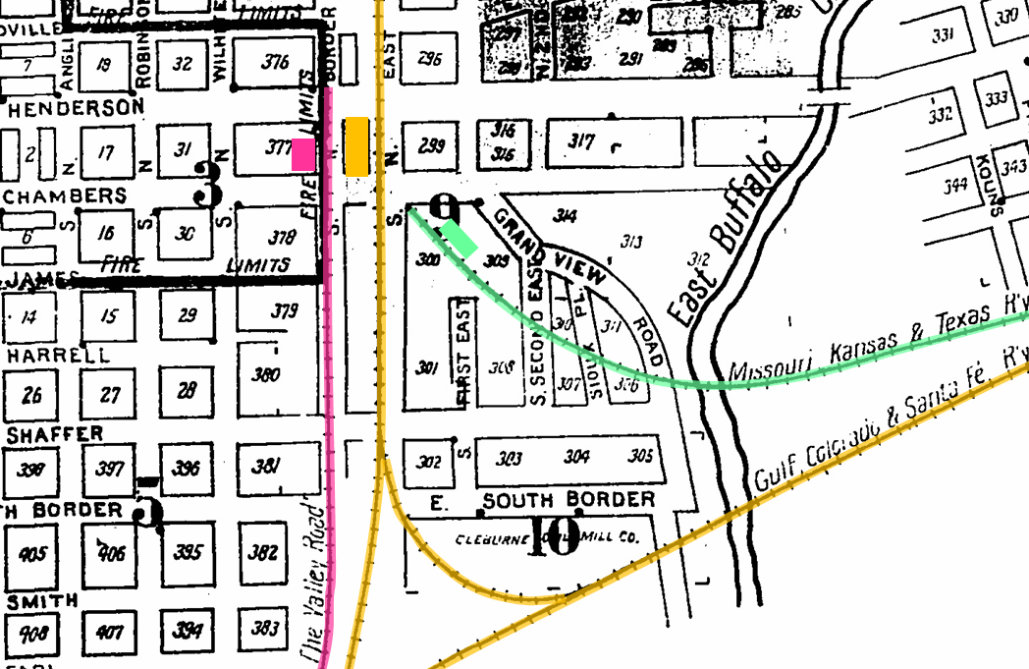

A Crossing of the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe Railway and the Trinity & Brazos Valley Railroad

|

Left:

Might this be Tower 43 near Cleburne? The photo (courtesy, Dillon Mcadams)

is from a collection of railroad items that belonged

to someone who worked for the Trinity & Brazos Valley (T&BV) or its successor,

the Burlington - Rock Island. Assuming it's associated with the T&BV,

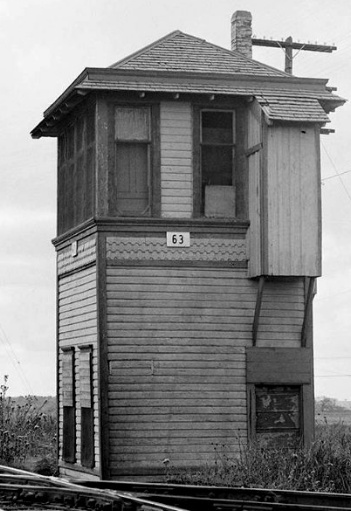

the acute angle fits Tower 43, but also Tower 63 at Mexia (below,

courtesy Tom Kline.)

Two photos of Tower 63 exist, and they show

features that do not appear in the photo at left. In particular, the

staircase at left rises perpendicular to the tower wall to reach the

initial landing in front of the building whereas the staircase below

rises parallel to the tower wall to reach the initial landing at the

corner of the building. The staircase at left faces the other railroad's main line while

the one below does not. Also, the rooflines are substantially different,

more easily seen in a higher resolution photo of

Tower 63. The tower at left is similar to

Tower 44 but wider and with different

surroundings. It can't be Towers 45 or

46, both of which had nearly right-angle crossings. Among towers for which photos have not yet been found, this photo's history and the tower's appearance fits well with the limited details known about Tower 43, but it's only a guess until a verified photo of Tower 43 is located. |

Soon after the Republic of Texas was admitted to the

United States in 1845, the U. S. Army began constructing a series of forts along

the Texas frontier. Fort Graham opened in the spring of 1849 along the east bank

of the Brazos River at the confluence of Little Bear Creek (the site is now

submerged by Lake Whitney.) In 1851, Fort Belknap opened north and west of Fort

Graham, more than a hundred miles distant. There was regular military traffic

between the two forts, and a frequent bivouac for troops was located about

twenty miles north of Fort Graham along Buffalo Creek, a site in Johnson County that had long been a crossing of trails and wagon roads. During

the Civil War, this crossroads became known as Camp Henderson. After Hood County

was created in 1866 from parts of western Johnson County, the community of

Buchanan, seat of Johnson County, no longer complied with state law requiring

seats to be within six miles of the geographic center of the county. Camp

Henderson was selected as the new seat and its name was changed to Cleburne to

honor Confederate General Patrick R. Cleburne.

The new county seat had a reputation as a

historic crossroads of commerce, so it is unsurprising that Cleburne's population tripled in the 1870s.

Investors became motivated to reach it by rail, and the first to do so was...a

more difficult answer than might be expected! The principal treatise on Texas railroad history is S. G.

Reed's 800-page reference, A History of the Texas

Railroads (St. Clair Publishing, 1941). Reed describes the initial effort

to build a railroad to Cleburne. It was...

...chartered November 23, 1876, as the Dallas & Cleburne Railroad Co. to build a narrow gauge between those cities but local capital could not be raised nor foreign capital interested. Three years later, on July 11, 1879, they reorganized and changed the name to the Dallas, Cleburne & Rio Grande Railway Co., intending like nearly all railroad projects at that time to go to the Mexican border. They finally built the 53 miles to Cleburne and ran a freight and a passenger train over the track to collect a promised bonus. After one each of these was run, service was abandoned. Finally Alex Sanger, J. B. Simpson and A. F. Hardle got behind the enterprise, interested northern capital, and got Dallas to give a bonus of $50,000 for a standard gauge road to Cleburne. A new charter was taken out on September 16, 1880, under the name of the Chicago, Texas & Mexican Central Railway Co. As the Santa Fe, Ft. Worth Branch passed through Cleburne, it was decided to buy this road which was done on July 6, 1882..."

There is much to unpack in Reed's paragraph. His primary

assertion is that finally a 53-mile line was built by the Dallas, Cleburne & Rio Grande

(DC&RG) from Dallas to Cleburne and that two trains were run over it, after

which service was suspended. Reed never says

that the line was actually built as narrow gauge (nor does he state that it was built in

1879, a mistake the Handbook of Texas

makes.) Reed's other assertion is that finally new investors got behind

the enterprise, a $50,000 bonus was offered, and a new charter was taken out in

September, 1880 under a new name, the Chicago, Texas & Mexican Central (CT&MC).

Reed says that Alex Sanger, et. al. finally...got behind the enterprise,

but this statement appears

after the 53-mile line had finally been built,

implying it was later in time.

But if that's true, why would a $50,000 bonus be offered for a standard

gauge road to Cleburne that either already existed as standard gauge, or

merely needed a conversion from narrow gauge? Reed doesn't explain, and he abruptly

fast forwards into the summer of 1882 when the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe Railway

(GC&SF, "Santa Fe") bought the CT&MC. Reed's use of the word "finally" in neighboring

sentences seems like an oddity that may imply something other than poor editing.

Railroad news was always of major interest in newspapers of that era, yet

not a single 1879 newspaper in Texas discusses any construction of any kind on a

Dallas - Cleburne rail line, let alone actually finishing it and running two

trains. The Fort Worth Daily Democrat, June 24,

1879 reported on a meeting held in Dallas that discussed forming a company to

build the DC&RG rail line. There was an article in early September stating that

teams surveying the planned route of the DC&RG were within fifteen miles of Cleburne (Brenham Weekly Banner,

September 5, 1879.) But articles describing any sort of actual construction

progress on

a Dallas - Cleburne rail line simply do not exist in 1879. There are numerous

newspaper articles in 1880 regarding the effort to build a Dallas - Cleburne

rail line, but, other than a groundbreaking ceremony, no actual construction

work was reported. Newspaper evidence from 1881 and 1882 combined

with a careful analysis of Reed's paragraph suggest that some

of his sentences may have been typeset out of

order, or perhaps a simple editing mistake resulted in sentences being misplaced in the paragraph. With all of the same sentences as above but in

a slightly different order, the best guess as to how the entire paragraph should read

is...

...chartered November 23, 1876, as the Dallas & Cleburne Railroad Co. to build a narrow gauge between those cities but local capital could not be raised nor foreign capital interested. Three years later, on July 11, 1879, they reorganized and changed the name to the Dallas, Cleburne & Rio Grande Railway Co., intending like nearly all railroad projects at that time to go to the Mexican border. Finally Alex Sanger, J. B. Simpson and A. F. Hardle got behind the enterprise, interested northern capital, and got Dallas to give a bonus of $50,000 for a standard gauge road to Cleburne. A new charter was taken out on September 16, 1880, under the name of the Chicago, Texas & Mexican Central Railway Co. They finally built the 53 miles to Cleburne and ran a freight and a passenger train over the track to collect a promised bonus. After one each of these was run, service was abandoned. As the Santa Fe, Ft. Worth Branch passed through Cleburne, it was decided to buy this road which was done on July 6, 1882..."

Newspaper articles from 1879-1882 establish

conclusively that there was

only one construction effort from Dallas to Cleburne, and it was executed and

completed by the CT&MC before it was purchased by Santa Fe in the summer of 1882. The effort began

in the summer of 1879 when new investors changed the

original 1876 Dallas & Cleburne name to add "Rio Grande" and

began surveying a right-of-way (ROW). During the survey, management changed the plan to standard

gauge, deeming a narrow gauge line as inadequate for the expected commerce and

connections (as reported by the

Dallas Daily Herald, January 5, 1882, in an article looking back on the

ordeal of the DC&RG's construction.) As the calendar turned to 1880, the DC&RG had yet to move

any dirt at all, and DC&RG management soon became focused on joining forces with

the newly formed Texas Trunk Railroad, which had been chartered to build southeast from Dallas

to Sabine Pass. A story in the Dallas Daily Herald

of May 8, 1880, reported an agreement between the two railroads and announced... "Hereafter,

we are informed, there is to be an identity of interests and management of the

Texas Trunk and the Dallas, Cleburne & Rio Grande roads." The story also

claimed the railroads would put "three hundred men, with the necessary

teams, grading apparatus, camp outfits, etc. on the line next Wednesday, May

12th. Work on this first ten miles, and, in fact, the balance of the fifty miles

between Dallas and Cleburne, is to be rushed through as fast as men and means

can do it." To no one's real surprise, the "three hundred men" never materialized

and the joint management scheme was apparently never consummated.

Above: Newspapers statewide

had varying opinions about the efforts of Dallas investors to build to Cleburne,

and those opinions likely evolved over time...except for the Fort Worth

newspapers, which universally derided Dallas' efforts to build any railroad

anywhere,

especially to Cleburne. Left to right:

Fort Worth Daily Democrat, March 25, 1876,

responding to an editorial by the Dallas Herald

("the leading newspaper of Northwest Texas") which had accused a Cleburne

correspondent of falsely claiming that Dallas was denigrating Ft. Worth's

efforts to seek additional railroads (a significant aspect of this report is

that it clearly cites the existence of the Cleburne

Chronicle

newspaper in 1876, a newspaper that was strangely silent if a

rail line was actually built into its town in 1879); Ft. Worth Daily Democrat,

June 18, 1879, explaining the real purpose of a "railroad meeting" in Dallas;

Austin

Democratic Statesman, July 31, 1879, wondering why Dallas is having

difficulty raising funds for the rail line to Cleburne;

Ft. Worth Daily Democrat, December 21, 1879,

quoting the Cleburne Chronicle

wondering if the

railroad to Cleburne will ever be built.

Below: More newspaper opinions...

Left to right:

Galveston Daily News, December 21, 1879,

reporting disgust among Cleburne citizens regarding the DC&RG;

Ft. Worth Daily Democrat, January 30, 1880,

advising Cleburne to forget Dallas and focus on Ft. Worth as a rail partner;

Ft. Worth Daily Democrat, September 29, 1880,

upping the snark in response to an editorial in the

Dallas Times; Ft. Worth Daily Democrat,

October 3, 1880, derisively commenting on the price of iron while mocking the

proclivity of the CT&MC (as the "CTRG&MC") to announce grand plans.

A review of the DC&RG's history published by the Dallas Daily Herald on January 5, 1882 explained that DC&RG management next approached Dallas investor Dr. F. A. Williams in the summer of 1880 with a proposition that if he could secure funding from his "Northern capitalists" friends, the DC&RG investors would transfer all of their rights to a new company capable of building a "first-class standard gauge road". Williams traveled to Washington and New York, and was able to bring in the Anglo-American Land & Claim Association, "a corporation that was handling large amounts of Scottish and European capital" as a major investor. Later that summer, the new CT&MC railroad was chartered and it secured a promissory bonus from the citizens of Dallas if fifty miles of track was completed toward Cleburne by the end of 1881. Beside the new name, a new charter was needed because the CT&MC wanted it to include both Paris and Mexico as authorized end points.

|

Although the CT&MC had not yet been chartered, the company that would

back it was being legally organized in July, as reported (top left) by the

Dallas Daily Herald on July 15, 1880.

The company needed to be established to be able to receive the transfer

of assets from

the DC&RG, which were mostly easements and rights-of-way already

negotiated. Although the new CT&MC charter was obtained in September, an article describing the groundbreaking ceremony held in downtown Dallas (top right, Dallas Daily Herald, September 10, 1880) used only the DC&RG name. This was because the vision of the CT&MC -- to create a rail line between Chicago and Mexico City -- necessarily included acquisition of existing railroads, not just new construction. To distant investors in Chicago and Europe, the CT&MC was promoting the idea that the DC&RG was one of the existing railroads to be incorporated into the grand plan, despite the fact that it did not exist and had yet to begin construction. Bottom Left: The Dallas Daily Herald of October 1, 1880 continued its regular cheerleading for Dallas railroads, hailing the CT&MC's effort to build from Chicago to Mexico City as equally important to that of the Texas & Pacific (T&P), which it described as "rapidly pushing through...toward the Pacific coast." At the time, the T&P tracks had just barely crossed the Brazos River west of Ft. Worth. It was another six months before the CT&MC began to advertise for contractors to do actual grading and track-laying (bottom right, Dallas Daily Herald, March 27, 1881.) Resurveying the entire route was the primary reason for the delay. The bonus for fifty miles of track required completion by the end of 1881, only nine months away. |

|

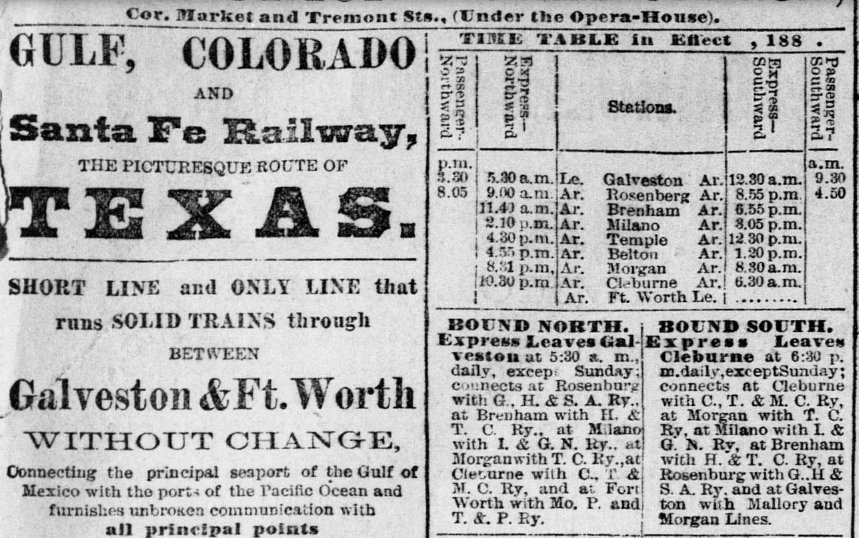

Returning to the original question, the GC&SF was the first

railroad to reach Cleburne, building north from Temple and arriving by late

October, 1881. Santa Fe advertised its timetable regularly in the

Galveston Daily News. The issue of October 23,

1881 listed Kopperl as the farthest station north on Santa Fe's line out of

Galveston. The November 1, 1881 issue listed Cleburne as the farthest station

north, noting that the timetable was "In Effect October 30, 1881". By

Thanksgiving, Santa Fe was "within six miles" of

Fort Worth and "...will

reach this place by December 1st." (Fort Worth

Daily Democrat, November 25, 1881.) Santa Fe was not, however, ready to

commence regular trains between Cleburne and Ft. Worth: "The Santa Fe road has so far

failed to run a regular train to Ft. Worth. Perhaps it is waiting for completion

of Chicago, Texas & Mexican Central to Cleburne (which will be done this week)

so that passenger trains to a city can be put on." (Fort Worth Daily

Democrat, January 1, 1882, in a strangely worded statement.) The CT&MC

completed its required fifty miles of track on the last day of 1881 and earned

its bonus, either $40,000 (one newspaper report) or $50,000 (another newspaper

report and Reed.) The remaining three miles into Cleburne was finished on January

7. Santa Fe service through Cleburne was underway by January 8, 1882 when Santa Fe advertising in the Ft. Worth Daily Democrat

began to list a connection "At CLEBURNE, with C. T. & M. C. Ry. for

Alvarado, Dallas and all points on that line." There were also reports that

the two railroads had agreed on railcar interchanges, mail routes, and other elements of

railroad cooperation.

|

The GC&SF was founded and headquartered in

Galveston where the local newspaper, the

Galveston Daily News, was one of the largest in Texas. New Year's

Day, 1882 saw a typical multi-font GC&SF ad (left),

although the "in effect" date was blank. The ad also failed to

list arrival and departure times at Fort Worth, perhaps because Santa Fe

wasn't actually running trains there yet! That didn't deter the Marketing

Department, which was already crowing loudly about their

"Solid Trains" between Galveston and Fort Worth "Without Change". They

also list a connection with the CT&MC at Cleburne, though it would not

exist for another week. (No worries! Ticket

agents would give travelers the honest truth by the fares they were willing to

sell.) Of note, Santa Fe's new tag line was "The Picturesque Route of

Texas", replacing "Texas Midland Route" (below,

from three days earlier) that had been in use for at least a year (and

which was unrelated to the Texas Midland Railroad; it would not exist for

another decade.) |

The GC&SF's ultimate arrival in Ft. Worth surprised no one. In only a few years, it had evolved to become an important and reliable railroad in Texas. It had been founded in Galveston in 1873 to build a railroad off the island that would not go through Houston (which was quickly developing into a rival shipping center.) Starting with a new bridge over Galveston Bay, construction had proceeded west to Arcola in 1877, onward to Richmond and Rosenberg in 1879, and then northwest to Brenham in 1880. In 1881, the GC&SF completed 100 miles from Brenham to Belton, which was the major town of central Texas north of Austin. Near Belton, the tracks passed through Temple, a construction camp named for the railroad's chief engineer, Bernard Temple. From the camp, the 128-mile main line to Cleburne and Ft. Worth was built in 1881, though some of the work was begun in the latter part of 1880. As the tracks were also being extended westward beyond Belton to Lampasas (1882) and Brownwood (1885), Temple was morphing into a significant city at the center of the GC&SF network, with tracks radiating out in three directions. All three branches remain intact today, owned by Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF), Santa Fe's successor.

|

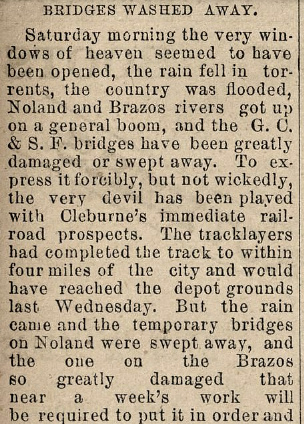

Compared to the financial issues of the Dallas - Cleburne effort during approximately the same timeframe, Santa Fe's rail line north from Temple was a snap to build, passing through (or near) various small communities, e.g. McGregor, Valley Mills, Meridian and Morgan en route. Valley Mills had "regular trains" before the end of June, 1881 (Brenham Daily Banner, June 24, 1881.) But north of Morgan, there was substantial difficulty in crossing the Brazos and Nolan rivers. Anticipating this, Santa Fe had commenced construction in late 1880 south out of Fort Worth: "...contracts for grading...were let, at Fort Worth, on the 19th..." (La Grange Journal, November 24, 1880.) Progress was swift: by late January, two-thirds of the distance to Cleburne had "...been graded, which is more than two-thirds of the work." (Fort Worth Daily Democrat, January 25, 1881.) A contract was let for grading from "...Cleburne to the Brazos River..." on February 1, 1881 (Fort Worth Daily Democrat, February 2, 1881.) Newspaper advertising was placed for quarrymen to work on the Brazos and Nolan River bridges: "Highest wages paid. Apply at Headquarters, Brazos River, 12 miles north of Morgan, Bosque county, Texas" (Galveston Daily News, March 27, 1881.) Fortunately, the engineers learned how vicious the floodwaters of the Brazos River could be before trains began operating over the new bridges. As reported by the Fort Worth Daily Democrat on October 11, 1881 (left and right, quoting the Cleburne Chronicle), an early October storm resulted in massive flooding that severely damaged the bridge over the Brazos and wiped out the temporary bridges over the Nolan River (there were three such bridges due to the twists and turns of the Nolan north of its confluence with the Brazos.) The bridge failures further delayed Santa Fe's arrival into Cleburne. Since they had graded the segment from Ft. Worth to Cleburne, they could have laid tracks and operated work trains over it, but they elected not to do so. The tracklayers finally reached Ft. Worth from the south around December 1, 1881. |

|

No evidence has been found to support Reed's claim that

precisely two trains were run from Dallas to Cleburne and then service was suspended.

With a dateline of Dallas, January 14, 1882, the Fort

Worth Democrat - Advocate of January 15, 1882 reported that "The

passenger train of the Chicago, Texas & Mexican Central railroad has arrived and

will be immediately put on the road between this point and Cleburne." (It

should be noted that the same article also reported a group of railroad men were

leaving that night for the east coast "...to try and perfect arrangements

for a consolidation of the interests of the Texas Trunk, the Chicago, Texas &

Mexican Central, and the new project known as the Gulf and Pacific railroad."

Nothing ever became of the Gulf & Pacific, and Reed does not mention it.) With a

new passenger train intact, the Dallas Weekly Herald of January 19, 1882

reported that the first CT&MC revenue passenger train from Dallas to Cleburne had

occurred the previous day and that it "...was

hailed by a crowd of Cleburnites, who had gathered at the terminus to welcome

it." The Dallas Daily Herald of

February 28, 1882 reported that "Tomorrow, passenger trains on the Chicago,

Texas & Mexican Central railroad will commence carrying the mails to and fro,

between this city and Cleburne." Mail as the newsworthy item tends to imply

that the trains were already carrying people, at least on a somewhat regular

basis.

Nevertheless, there is plenty of evidence indicating that the CT&MC was having severe financial,

physical and operational problems. The

Fort Worth Daily Democrat, March 11, 1882,

seemed happy to report... "The Chicago, Texas and Mexican railroad, which

has one end about two miles from Dallas and the other in the vicinity of

Cleburne, is not a railroad after all. The state inspector has passed over the

line twice, and each time he has declined to accept the road as completed."

This was only a few days after the same newspaper had reported, on March

3rd,..."A force employed by the Western Union Telegraph Company, putting up

a line for the Chicago, Texas and Mexican Central Railroad Company, between

Dallas and Cleburne, quit work and refused to allow any more wire to be strung,

because they cannot get pay from the railroad company for work. The employees in

other capacities refuse to work for the same reason."

Fort Worth Daily Democrat, March 28, 1882 |

The CT&MC was in deep financial

difficulty (left),

with deputy sheriffs seizing the rolling stock and running the trains to

ensure that these assets did not disappear. Because of its state

charter, the CT&MC had to be certified by a state inspector, but his

approval was not forthcoming. (below,

Galveston Daily News, March 9, 1882) Right: A correspondent of the Fort Worth Daily Democrat met with a CT&MC executive to discuss the situation with the railroad. Notwithstanding flimsy excuses about the roadbed and the weather, the most significant comment was the certainty that the railroad would "...soon be relieved of its present embarrassment...", no doubt alluding to the rumors of its acquisition by Santa Fe. |

Fort Worth Daily Democrat, April 6, 1882 |

The Fort Worth Daily Democrat

of March 3, 1882 reported a well-spread rumor "...in railroad circles that the company proposes to clear

the road of debt, and that negotiations on that basis are going on with the

Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe for the Chicago, Texas and Mexican Central."

Rumors about the Santa Fe and the CT&MC, but with much greater intrigue, had

been around since mid-January. The

Dallas Weekly Herald of January 12, 1882 commented on a lengthy article

that had appeared in the

Ennis Review weaving a modicum of facts

with some rank speculation to allege a conspiracy among the GC&SF, the

Houston & Texas Central (H&TC), and the CT&MC to "out-flank" Jay Gould.

Gould controlled both the T&P, which had an east/west line through Dallas and

Ft. Worth, and the Missouri - Kansas - Texas ("Katy") Railroad, which

had a line to Ft. Worth from their bridge over the Red River near

Denison. Gould also controlled the International & Great Northern (I-GN),

a major north/south railroad connecting Laredo, Longview, Houston and Galveston.

Gould leased all three of these railroads to his Missouri Pacific

(MP) Railroad, which had tracks to St. Louis from

Texarkana. The rumored plot centered on building

a line to Paris to meet the St. Louis San Francisco ("Frisco") Railway which in

1880 had begun an extension of their network from Missouri southwest through Ft.

Smith, Arkansas toward Hugo, Oklahoma where they intended to

bridge the Red River into Paris.

With the Frisco connection, a line through Paris would provide a

shorter route to St. Louis from Dallas, Houston and Galveston compared to the

Katy's route crossing the Red River at Denison. The H&TC line from

Houston to Denison passed through Dallas,

so a branch from Dallas to Paris would allow H&TC's St. Louis and Kansas

City traffic to prefer

Paris over Denison, a possibility that alarmed the Gould syndicate. Santa Fe

didn't serve Dallas, a problem easily solved if it acquired the CT&MC to create

a Dallas branch from Cleburne that could be extended northeast to Paris. The

CT&MC charter specifically included authorization

to build between Cleburne and Paris, and that was the only thing that made it a player in this intrigue. For its part, the CT&MC

reportedly had begun surveying "...between

Dallas and Paris for the location of depots." (Dallas

Weekly Herald, December 29, 1881.) If this seems a bit suspicious for a

company known to be essentially bankrupt, a report in the

San Marcos Free Press of January 26, 1882

discussing the CT&MC added an even bigger

claim, that... "Five miles of grading from Dallas toward Paris are

completed, and the line is located as far as Farmersville -- forty-two miles.

Two hundred men are now employed on the the line northeast of Dallas, and in a

few days the company expects to have 1,200 men at work, and the road will be

rapidly pushed through to Paris where it is to form a junction with the St.

Louis & San Francisco road which will be extended south through the Choctaw

nation next summer." This construction activity attributed to the

CT&MC seems highly implausible...

...unless, of course, Santa Fe was

funding the effort, knowing that they would soon acquire the CT&MC. The

Ennis Review had claimed the existence of a secret agreement between Santa Fe and the CT&MC dating back a full year to the spring of 1881

in which the companies had agreed to

split the cost of building a line from Dallas to Paris. Both would have rights

to operate from Cleburne to Paris and they would share profits made over the line.

The agreement was apparently never finalized, reportedly because both Gould and

the Frisco got wind of it, but more likely because Santa Fe realized that the CT&MC didn't have the

finances to sustain itself for very long. Why make a long-term agreement with

the CT&MC when they can be bought instead? Since

Gould's T&P already served Paris on a line from Texarkana to

Ft. Worth via Sherman,

he had begun to examine the possibility of taking over the Frisco so

he could control the Paris gateway.

Meanwhile, H&TC investors decided they would start a branch from their main line

south of Dallas (near Ennis) to run northeast to Paris. They had already chartered the

Texas Central (TC) Railway in 1879 for the main purpose of building a northwest

branch into the Texas Panhandle. But with foresight of the Frisco's intention to

build through Oklahoma and bridge the Red River at Hugo, the TC charter included

rights to build a northeast branch to Paris.

Construction on this branch began in

1882 and reached Kaufman and

Terrell before the TC went into a lengthy

receivership. As part of the TC's reorganization, the branch toward Paris was

sold off and completed by the Texas Midland Railroad in the 1890s.

Santa Fe did,

indeed, buy the CT&MC, mainly to gain access to Dallas and the

right to build to Paris. The property officially transferred to Santa Fe on

August 1, 1882. While this was a good, strategic move for the GC&SF, it did

nothing to solve their biggest problem: they were entirely dependent on local

traffic. Unless the GC&SF could find a partner to stimulate traffic from

out-of-state markets, they were destined to become subservient to the big

railroads in Texas. The obvious suitor was the much larger

Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe (AT&SF) Railway. The AT&SF viewed Galveston as an attractive port for agriculture

exports from the high plains. The GC&SF's main line from Ft. Worth to Galveston

would be a boon to AT&SF's network if the two railroads could establish an

appropriate interchange point. Negotiations resulted in an 1886 agreement under

which the AT&SF would acquire the GC&SF on favorable terms if the GC&SF

completed three construction projects within a year, specifically, Ft. Worth to

Purcell, Oklahoma (where it would meet an AT&SF line building south);

Dallas to Paris (where

it would meet the Frisco); and

Cleburne to Weatherford

(where a connection with the T&P would establish a shortcut to west Texas,

bypassing Ft. Worth.) The GC&SF was able to lay 300 miles of track in one year

to complete all of these projects, a substantial amount by any measure. The

acquisition proceeded as planned in 1887 and the GC&SF began operating as a

wholly-owned subsidiary of the AT&SF.

Having acquired the CT&MC,

railroad operations through Cleburne for the next twenty years were the

exclusive province of Santa Fe. Other roads passed nearby -- the Katy, building south from

Ft. Worth, had passed 13 miles east of Cleburne near Alvarado

in the spring of 1881 and had been crossed there in the fall by the CT&MC. Santa

Fe, building its branch from Cleburne to Weatherford, and the Ft. Worth & Rio

Grande, building from Fort Worth to Brownwood, had crossed in Cresson, 20 miles

west of Cleburne, in 1887. Although the TC's northwest branch had reached

Whitney in 1879, a projected 30-mile tap line from

Cleburne was never built (contrary to the

assertion

by the Handbook of Texas.) And consistent

rumors that the Waxahachie Tap would build west to Weatherford via Cleburne

proved unfounded.

In the early 1890s, Santa Fe began to consider Cleburne

for the site of its Central Machine Shops. Temple and other Texas cities were also in the running, and

the decision-making process became highly politicized. It did not help that

citizens of Cleburne were beginning to perceive the disadvantage of being a

one-railroad town. "So low were the freight rates of the Missouri, Kansas &

Texas Railroad to Alvarado, that Cleburne merchants bought goods and had them

shipped to Alvarado, then paid for having them hauled to Cleburne from Alvarado."

Citizens of Cleburne were also "...unable to understand why the Santa Fe

could deliver coal in Dallas at the rate of one dollar per ton freight, while

Cleburne people were charged one dollar and seventy-five cents freight on each

ton delivered in Cleburne. The fact that the coal hauled into Dallas had to pass

through Cleburne first made the Cleburne people wonder why the company could

charge less for a longer haul than it could for a shorter one."

(G. H. Gay, The Early Development of Cleburne,

Masters Thesis, North Texas State College, August, 1950)

In 1897, Santa

Fe signed a contract with a committee representing Cleburne agreeing to locate

their machine shops there in exchange for land. G. H. Gay's Masters Thesis does

not state that Cleburne offered cash, whereas it does report sizable land and cash

donation offers from Dallas ($100,000), Ft. Worth ($75,000)

and Temple ($60,000). Notwithstanding whether there was cash involved,

the critical factor appears to have been the establishment of free flowing

artesian wells in Cleburne in the early 1890s. Cleburne had by far the best

water supply of all of the competitors, and vast quantities of water were

critically important to a mechanical shop focused on steam engines. (During a

drought in the mid-1890s, Cleburne emphasized their point by sending a tank car

full of water to Santa Fe's offices in Ft. Worth.) The shops became operational in 1899

and remained a major contributor to

Cleburne's economy until they closed on September 29, 1989. The clamor for rail competition

at Cleburne did not subside, however, and

it was heard by the Katy. In 1902, the Dallas, Cleburne & Southwestern

(DC&S) Railway

built a 10-mile spur from the Katy main line at Egan into Cleburne.

|

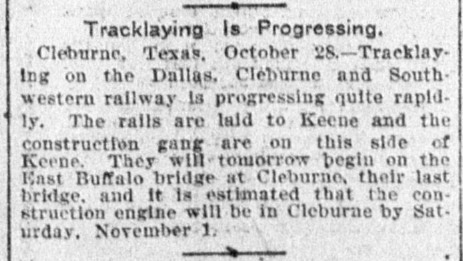

Left: The

Houston Daily Post of October 30, 1902 reported the tracks of the

DC&S had nearly reached Cleburne. Right: The Weatherford Weekly Herald of November 20, 1902 reported the first train into Cleburne on the DC&S. The article speculates on additional DC&S construction, but nothing further was ever built. Reed explains that the DC&S was "...financed by the parent Katy and was leased to the Texas Katy..." The spur was abandoned in 1924. |

|

Above: the Katy

depot in downtown Cleburne (from Images of

America, Cleburne by Mollie Mims)

The last railroad to reach Cleburne was the Trinity

& Brazos Valley (T&BV) Railroad in 1904. It had been chartered in 1902 by two Houston men who believed

there was room for another railroad between Ft. Worth and Houston. Although the

charter included connecting Cleburne with Beaumont, their initial effort was to

build between Cleburne and

Mexia, a southwesterly route across a major farming

region where they expected connections with other railroads would produce

adequate returns. They were, in essence, creating an east/west agricultural branch line that

would connect with three major north/south railroads at Cleburne (Santa Fe),

Hillsboro (the Katy) and Mexia (the H&TC.) Construction began with a segment

between Hillsboro and Hubbard in 1903, followed by

extensions west to Cleburne and east to Mexia that were completed in early 1904.

Revenue quickly proved to be inadequate, and the financial backers on the east

coast were unwilling to provide more funding. Just as the situation was turning

dire, the T&BV was acquired by the Colorado & Southern (C&S) Railway in 1905 as

part of a massive and unusual plan conceived by a member of the C&S Board of Directors, B.

F. Yoakum.

Yoakum was a native Texan with vast experience in Texas

railroading. He was born in 1859 in Tehuacana, a small community close to Mexia

(and only a mile from the new T&BV tracks.) In addition to being on the C&S

Board of Directors, Yoakum was, at age 46, the chief

executive of the Frisco and the Chairman of the Executive Committee of the

Board of Directors of the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad. He had previously been an executive

with the GC&SF. Yoakum had built or acquired some

railroad properties in south Texas, collectively known as the Gulf Coast Lines

(GCL.) Yoakum wanted to combine them into a railroad that could compete with

Southern Pacific (SP) in the coastal region of Texas and Louisiana. For his idea to be successful, Yoakum needed a connection

between his GCL lines in south Texas and his Frisco and Rock Island lines in north

Texas. SP's H&TC subsidiary owned the main route between Houston and Dallas, and

it was particularly galling to Yoakum that he had to give SP overhead traffic to bridge his own

railroads.

Yoakum obtained a state railroad charter authorizing

construction from Fort Worth to Galveston via Dallas and Houston. He had the

Rock Island lay tracks to Dallas but did not build the southward extension.

Instead, he negotiated a massive contract with SP to route Frisco and Rock

Island traffic exclusively on SP lines to the Gulf, but the contract was

rejected by RCT. Rather than proceed with building the Rock Island extension

south from Dallas, he teamed with the C&S to acquire the T&BV (with Rock

Island gaining half ownership.) The T&BV

served Yoakum's purposes, especially since its existing tracks and charter

rights were

located midway between Houston and Dallas. After building east from Mexia to Brewer

(which became Teague, Yoakum's mother's maiden name), the T&BV built a

north/south main line through Teague between Houston and

Waxahachie, with rights on the Katy's tracks from

Waxahachie into Dallas. Yoakum also negotiated rights for the T&BV to use Santa

Fe's line between Ft. Worth and Cleburne. The T&BV chose not to make

intermediate stops along the route to Fort Worth, but RCT ruled that this

violated their state charter. On December 16, 1907, RCT ordered the T&BV to

begin serving intermediate points along Santa Fe's tracks to Ft. Worth with both

freight and passenger service. By the end of 1907, the T&BV served

Houston, Dallas and (despite RCT's ire) Ft. Worth. At Cleburne, the T&BV tracks crossed the

Santa Fe a little over two miles south of downtown. To control the crossing in

accordance with the new interlocker law that had become effective in 1901, Tower

43 was authorized to commence operation on July 7, 1904 by the Railroad

Commission of Texas (RCT).

Tower 43's first appearance in a published RCT

Annual Report was in a table dated October 31, 1904. Tower 43 is listed as a 12-function mechanical interlocker located "South of

Cleburne". In the 1906 list, the location became "Cleburne" and the function

count remained unchanged. The 1906 list also included a comprehensive set of

statistics which indicated an average of 20 trains per day had passed Tower 43

over the prior year. The 12-function interlocker implies a simple crossing

consisting of a home signal, a distant signal and a derail in each of the four

directions. There are no indications of any exchange tracks at Tower 43, nor

should there have been given that the two railroads could more easily exchange traffic in

downtown Cleburne only two miles away. RCT documentation archived at DeGolyer

Library, Southern Methodist University describes Tower 43 as a 45-degree

crossing at Santa Fe milepost 315.2 located 2.35 miles south of Cleburne.

In 1916, RCT began to publish

information for each tower identifying the railroad responsible for operations.

While Santa Fe was listed as being responsible for staffing Tower 43, that does

not necessarily imply that it was always that way. The T&BV's receivership in

1914 would have been a major concern for Santa Fe if the T&BV was in charge of

staffing Tower 43. This was Santa Fe's main line; they could not afford any

disruption to operations that could easily occur if maintenance or operations staffing

issues arose for the T&BV (particularly the

ability locate replacements on short notice, and the ability to keep trained employees

who might opt for a more reliable employer.)

Since the

crossing did not exist when the new interlocker law took effect in 1901, the

second railroad (the T&BV) would have been responsible for the capital

outlay for the tower. Typically, but not always, the company responsible for the capital outlay

led the design and construction, and also took responsibility for operations and

maintenance staffing. RCT's regulations required recurring expenses (labor and

materials) to be shared

between the railroads on a weighted function basis, hence 50/50 for Tower 43

since each railroad had half of the twelve functions. Since Santa Fe had

by far the most operations past the tower, they had a critical interest in

keeping Tower 43 fully operational. Thus far, no information has surfaced to

show definitively which railroad staffed the tower at the outset, nor, for that

matter, which railroad led the tower design and construction. RCT's information

establishes that at least by 1916, Santa Fe had the staffing responsibility.

Serving Houston, Dallas and Ft. Worth and carrying all of the Frisco and Rock

Island overhead traffic with the GCL, the T&BV competed aggressively with H&TC's

north/south line. Eventually, however, Yoakum's entire rail conglomerate failed,

splintering into separate components. The T&BV remained operational during a

lengthy receivership that began in 1914 and ended in 1930. Coming out of

bankruptcy, a new entity, the Burlington - Rock Island (B-RI) Railroad, was

established to take over the T&BV. Except for the T&BV's north/south main line

(which continues in active use under BNSF ownership), the interim growth of the

rail network along with substantial improvements to rural highways (making it

easier and quicker to truck products to the nearest major shipping point) had rendered much of the T&BV unnecessary.

The B-RI commenced abandonment proceedings; the 30 miles between Cleburne

and Hillsboro was the first segment removed, in 1932. This also eliminated

the need for the Tower 43 interlocker, which was abandoned on October 11, 1932.

The other railroad into Cleburne was the Northern Texas Traction (NTT)

Company electric interurban railway from Ft. Worth. It was built in 1912 by an

NTT subsidiary, the Fort Worth Southern Traction Company, and was subsequently

reorganized into the Tarrant County Traction Company, a component of the NTT.

Interurban service to Cleburne terminated in May, 1931.

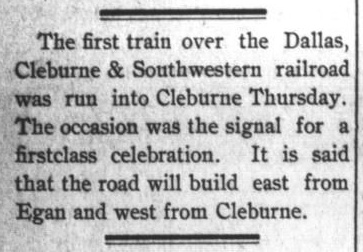

Above Left: historic steam

railroads near Cleburne; solid line tracks are still intact

Above Right: Trinity & Brazos

Valley (left) and Santa Fe (right) depots in Cleburne c.1910. The Santa Fe depot

incorporated a Harvey House restaurant above it which closed in 1931.

Below: The entire Santa Fe

depot structure was modified into a single story facility in 1942. This

structure remained intact until it was demolished as part of the construction of

an overpass on U.S. Highway 67 in 1994. It was still being used by Amtrak at the time,

but Santa Fe no longer had any offices there. (undated photo, courtesy Cleburne

Railroad Museum.)

Above Left: The T&BV depot at

Cleburne closed as a railroad station in 1932, but was repurposed at various

times over many decades. Fire damaged the structure and a demolition order was

issued by the city on April 17, 1996. Attempts to preserve the building were

ultimately unsuccessful and it was razed in 2002. (Texas Historical Commission

photo, August 1, 1974) Above Right: Santa Fe

passenger station and Harvey House restaurant at Cleburne, built in 1894; by

the time this photo was taken in 1937, the Harvey House had been closed for six years (J F Curry photo, Dane Williams collection)

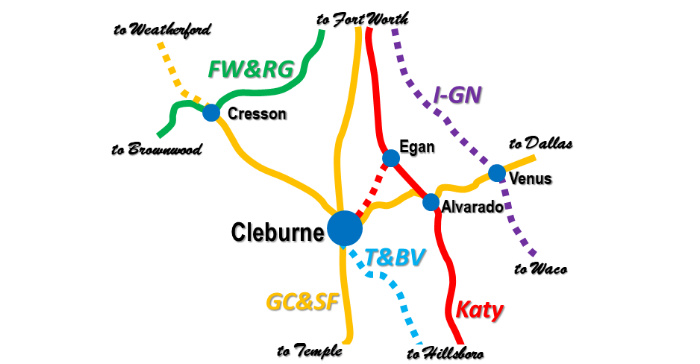

Above: Overhead imagery from 1956

((c)historicaerials.com) and a Sanborn Fire Insurance map from 1918 correlate

the locations of the three passenger stations in downtown Cleburne. Though the Katy

(green) had been out of service since 1923 and the T&BV (pink) since 1932, both

stations remained standing in 1956. The Santa Fe depot (orange) was still in use

in 1956. Below: Using the same

color scheme as above, this snippet from the 1918 Sanborn Fire Insurance index

map of Cleburne has been annotated to show the larger perspective of where the

depots were located relative to the tracks entering Cleburne. The T&BV and Santa

Fe depots were on the northwest and northeast corners, respectively, of the

intersection of Chambers St. and Border St. The Katy depot was on the southeast

corner of the intersection of Chambers St. with East St., now called Front St.

Above Left: Looking southeast from the corner of

Chambers and Front streets where the Katy depot sat, the track in the

pavement would have passed in front of the station. Above Right:

Looking north along Border St. at its intersection with Chambers St., the T&BV

depot was to the left, the Santa Fe depot to the right. (Google Street View

images November, 2019.)

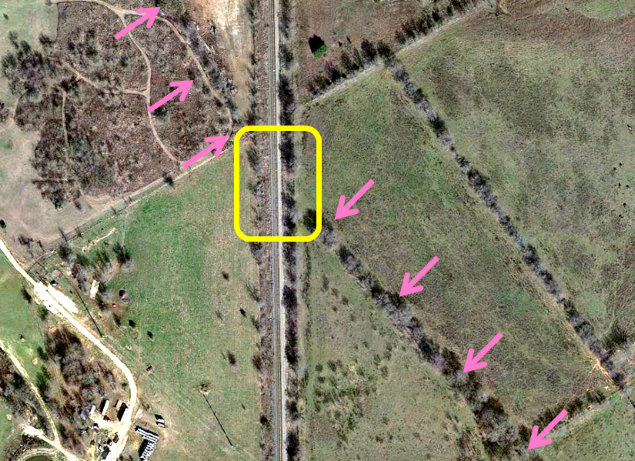

Above: A birds eye view (left, c.2008) and a satellite

view (right, c.2019) both show a tree line (pink arrows) as the marker for the

path of the T&BV at the Tower 43 crossing (somewhere in the yellow rectangle.)

The site is on private property, and after 90 years, it would likely take some digging

to find any trace of the foundation of Tower 43.

Above Left: The photo at the top of the page (courtesy

Dillon Mcadams) shows an unidentified tower, reproduced here with

magnification. The source of that photo makes it likely that it depicts a tower

that controlled a T&BV crossing. As such, the angle of the crossing limits the

tower most likely to

either Tower 63 at Mexia (above

right, DeGolyer Library photo) or Tower 43 south of Cleburne,

of which no confirmed photo has been located. Of

all of the tower photos in the collection of this website, the one that most closely resembles

the tower at left is the one

above center, Tower 44 in

Hillsboro (Ken Stavinoha collection) which controlled a crossing of the T&BV, the

Cotton Belt and the Katy. Tower 44 was commissioned by RCT on the

same day as Tower 43, July 7, 1904. Two of the other three towers that served

the T&BV, Tower 45 in Malone, a crossing of the

I-GN, and

Tower 46 in Hubbard, a crossing of the Cotton Belt, were also commissioned that

day. This cannot be sheer coincidence; the T&BV was apparently working to get all of its towers

activated simultaneously, presumably to make it simpler for its staff to adjust

to the new interlocker procedures across the entire main line (recall

that in 1904, the T&BV's endpoints were Cleburne and Mexia.) Tower 63 at Mexia did not commence operations for another two years, on April 26, 1906,

but that is simply because the T&BV rails did not cross the H&TC south of Mexia

until Yoakum began construction of the eastward extension to Teague in late

1905.

Towers 44 and 63 share the "fish scale" pattern between the

floors and have similar roof features. Like Towers 43, 45 and 46, they are also known to be tower locations where the T&BV,

as the last railroad to reach the crossing, would have been responsible

for the capital outlay and thus likely to be responsible for the tower design

and construction (and since Towers 43 and 44 were obviously being built simultaneously, commonality of architectural features is a reasonable

expectation.)

Tower 44 and the tower on the left share a staircase layout that was not

uncommon in Texas (e.g. Tower 9, and several

others.) The point is...the staircase design alone does not prove a T&BV

heritage for the tower at left (nor Tower 44, for that matter.) Unfortunately, the image at left lacks sufficient clarity to

determine whether the "fish scale" pattern is present, but it

definitely does not share the roofline of Tower 63. Given the design and location of the Tower 63 staircase that appears

in the photo at the top of this page, and considering the roof line details of Tower 63 that do not appear in the tower image at left,

it seems unlikely that the photo at left is Tower 63. The acute angle of

the crossing then makes it most likely that the photo at left is Tower 43.

Positive identification awaits discovery of a verified photo of Tower 43.

Honoring Cleburne's

railroad heritage, the newly reformed Cleburne Railroaders of the American Association of

Professional Baseball began playing their home games in 2017 at The Depot at

Cleburne Station. The Railroaders were a Texas League team in the early 1900s

for which future Hall of Fame centerfielder Tris Speaker played. (Above,

Astroturf.com; Below,

Monica Faram)