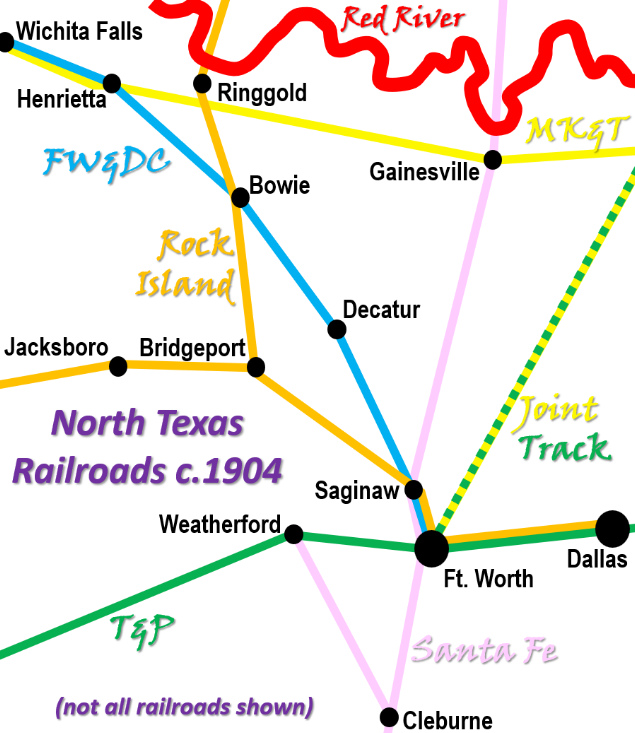

Texas Railroad History - Tower 29 - Saginaw

A Crossing of the Chicago, Rock Island &

Gulf, the Fort

Worth & Denver City, and the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe railroads

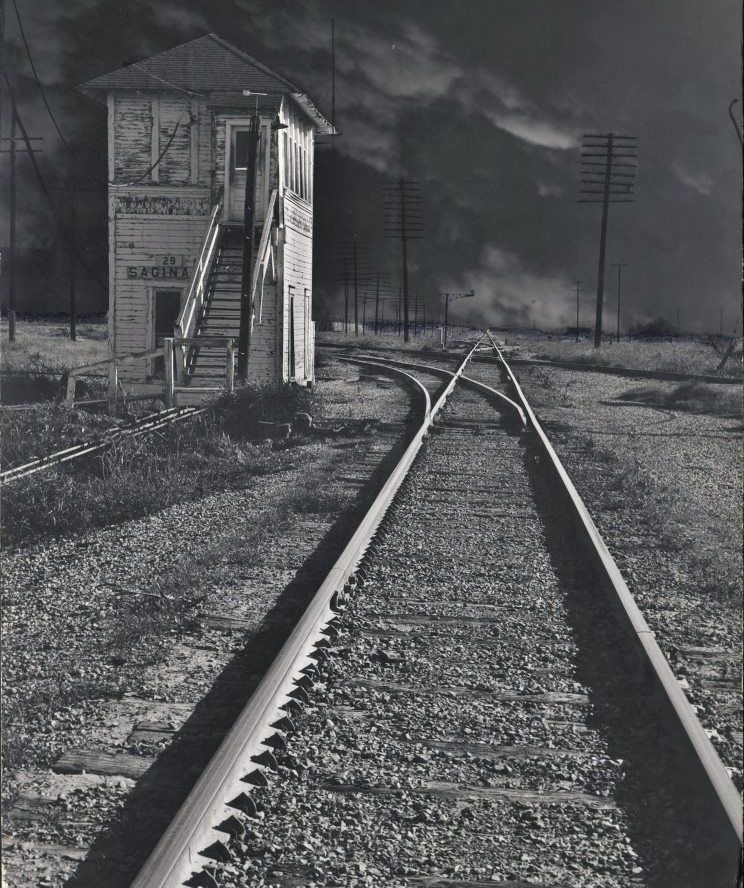

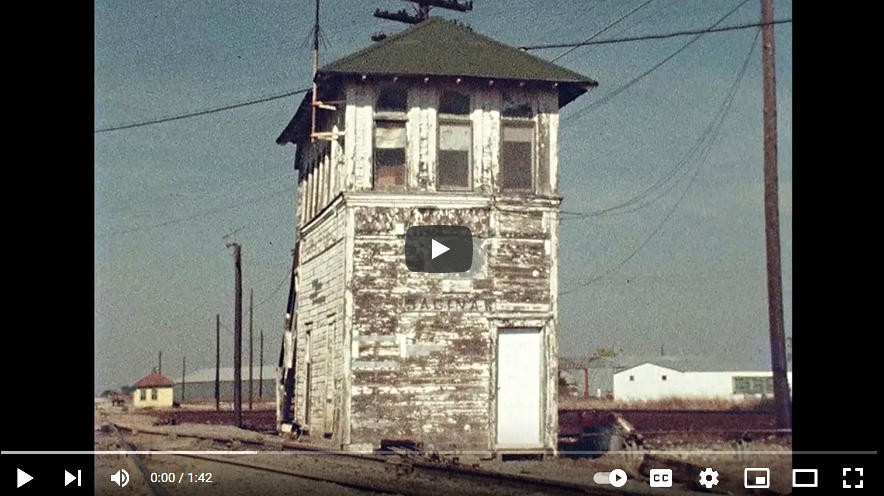

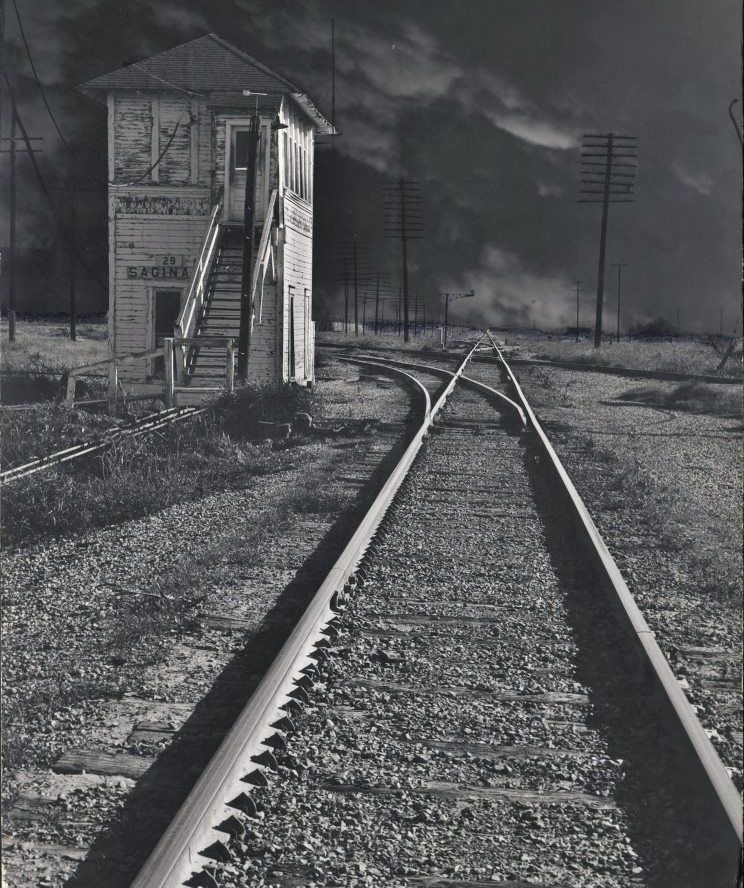

Above: Railroad executive John W. Barriger III took this photo of Tower 29 from

the rear platform of his northbound business car as his train sped through

Saginaw on Chicago, Rock Island & Gulf tracks. The date is unknown,

probably in the mid to late 1930s. Barriger's view is southeast

toward Ft. Worth, where his trip originated.

Below: Northbound Rock Island RDC-3 No. 9015 crosses the Santa Fe tracks at Tower 29 on April 11, 1962. (Tom Hughes photo,

from Down South on the Rock Island by

Steve Allen Goen, (c) Four Ways West Publications, 2002)

General Grenville M. Dodge gained fame and fortune as the Chief Engineer

for Union Pacific (UP) supervising the construction of its (eastern) portion of the nation's first

transcontinental railroad. With its completion in 1869, Dodge found his services

in demand for new projects. In 1872, he became the Chief Engineer of the Texas &

Pacific (T&P) Railway which had been chartered by Congress in

1871 to be the country's second transcontinental railroad, from

Texarkana to San Diego. The

Panic of 1873

disrupted construction progress at Dallas, and track-laying

ultimately stalled

for financial reasons at Ft. Worth in 1876. Dodge

returned to the T&P in 1879 when the work restarted and stayed with it even when it became clear that -- far from San Diego -- the T&P's western

extent would be limited to the

remote west Texas outpost of Sierra Blanca, thence sharing a Southern Pacific

track into

El Paso. While Dodge was leading the T&P westward,

his reputation and his presence in Ft.

Worth railroad society for several years enabled him to

approach the Fort Worth & Denver City (FW&DC) Railroad with an offer to build

its proposed rail line from Fort Worth to

Colorado. S. G. Reed, in his reference tome A

History of the Texas Railroads (St. Clair Publishing, 1941) explains the

offer:

"General Dodge offered to build,

furnish all material and to equip the road to Denver, Colo., or any other point

in Colorado ... for $20,000 a mile in stock and the same amount in bonds. The

stockholders of the F. W. & D. C. accepted his offer and the contract was signed

on April 29, 1881. He organized the ... Texas & Colorado improvement company of

which he was President and principal owner."

The FW&DC had been chartered nearly a decade earlier

(June 6, 1873) with a plan to build to the Texas Panhandle to meet Colorado &

Southern (C&S) rails coming south from Denver. Numerous financial and organizational obstacles had prevented

the start of construction, hence Dodge's offer found a receptive audience. In creating

his construction company to build the route

with mileage-based remuneration, Dodge mimicked the approach of rail magnate Jay

Gould, whose offer to build the T&P west from

Fort Worth under precisely the same arrangements was accepted by T&P

stockholders (with Dodge coming back to lead the effort in 1879.)

Needing a place to which FW&DC materials could

be shipped and stored, Dodge chose a location -- eventually called

Hodge Junction -- served by the T&P Joint Track, so named

because it was shared with the Missouri, Kansas & Texas (MK&T) Railroad under a

long term agreement. To the public, the MK&T was "Missouri

Pacific" (MP) because Gould, as President of the MK&T, had leased it to MP, a

Midwest railroad he controlled into which he was consolidating various rail

properties. Gould had also become President of the

T&P thanks in large part to Dodge's rapid construction success in west Texas, hence Dodge undoubtedly obtained favorable

arrangements from Gould at Hodge Junction. [...perhaps even more favorable than one might expect.

Indicative of their strong bond, when Gould acquired all of the stock of the International &

Great Northern (I&GN), Texas' largest railroad, in a June, 1881 stock swap for MK&T

securities, he

gave the I&GN certificates to Dodge, arguing in court that possession of them in Ft. Worth

made Dodge the I&GN's owner, thus constituting compliance with state law requiring Texas railroads to be owned and

headquartered in state, a provision that neither Gould nor the MK&T could

meet...but that's another story.]

In late 1881, Dodge was running multiple construction projects

simultaneously, finishing the T&P into Sierra Blanca while also building the New

Orleans & Pacific from Shreveport to New Orleans and the I&GN from San Antonio

to Laredo. He was also able to commence

FW&DC construction northward from Hodge Junction on November 27, 1881,

making arrangements to

use the

Joint Track to access passenger facilities downtown. (In

1890, the FW&DC would build its own line into downtown.) Dodge made rapid progress; trains

were operating forty miles to Decatur by May, 1882. Four miles

north of Hodge Junction, the FW&DC tracks passed east of the tiny community of Dido,

one of the earliest settlements in Tarrant County. Many of

its residents relocated to the railroad, and according to the

Handbook of Texas, the new town was named

Saginaw after the Michigan hometown of local landowner J. J. Green. (Although

Dido faded away, some folks say they still live there while others claim it

became a ghost town. The presence of Dido-Hicks Rd. and Morris-Dido-Newark

Rd. suggests that Dido may be gone, but it's not forgotten. The well-kept

Dido

Cemetery is the final resting place of famed Texas songwriter

Townes Van Zandt.)

|

Left: The next town beyond Decatur was

Bowie, which gained rail service in early June,

1882.

The stage service to Henrietta from Bowie was no longer needed when

FW&DC rails reached there several weeks

later. (Fort

Worth Democrat - Advance, June 7, 1882)

The initial segment of

FW&DC construction, 110 miles from Hodge

Junction to Wichita Falls, was completed in September, 1882. Work was

suspended for three years before continuing northwest in 1885, but only

34 miles of track (to Harrold) was laid that year. Restarting in

May, 1886, the FW&DC moved quickly, passing through the new and

future towns of

Quanah, Amarillo and

Dalhart. In the spring of 1888, rails

reached the new settlement of Texline on the

New Mexico border in the far northwest corner of the Texas Panhandle, meeting C&S rails that had been

laid south from Denver. In April, 1888, trains began operating between

Denver and Ft. Worth.

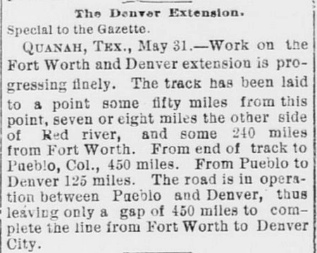

Right:

FW&DC progress reported by the

Fort Worth Daily Gazette, June

1, 1887 |

|

While Dodge was building north from Ft. Worth in

early 1882, tracks of the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe (GC&SF) Railway were

entering Ft. Worth from the south. This was a

rather remarkable accomplishment considering that at the end of 1880, the GC&SF

main line ran only from Galveston to

Brenham. In 1881, track-laying proceeded another

hundred miles to Temple, site of a major

construction camp, and continued west to Belton, ostensibly aiming for the Texas

Panhandle (consistent with the Colorado component of the railroad's

name.) The idea of building a branch line to north central Texas had been

included in the GC&SF's charter, and the decision was made to proceed

immediately with construction from Temple to Ft. Worth to ensure a share of the

north Texas railroad development

in progress. The work was accelerated and almost all of the 128

miles from Temple was completed in 1881 (totaling more than 200 miles from Brenham in twelve

months.)

This rapid expansion northward did

not solve the GC&SF's biggest problem -- it was almost entirely

dependent on local economies. The Port of Galveston

created traffic, simply too little of it. When Gould purchased the Galveston, Houston & Henderson

Railroad on August 1, 1882, he gained control of the only other

bridge

across Galveston Bay. Through Houston, this

gave Gould rail lines all the way from Galveston to St. Louis and beyond, whereas the GC&SF had no

captive market. Unless it could find a partner to stimulate

out-of-state traffic, it would remain ripe for an unwanted takeover. The Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe (AT&SF) Railway, a large, high plains and

southwestern railroad ranging from Kansas to California, did not have a Texas

presence, and Galveston was an attractive port for agriculture exports from the

Plains states. The GC&SF would mesh well with AT&SF's

network if the two railroads could establish an appropriate interchange point.

GC&SF President George Sealy

negotiated an agreement under which the AT&SF would acquire

the GC&SF on favorable terms if the GC&SF completed three construction

projects within a year. One of these projects was a line north from Ft.

Worth through Gainesville to the Canadian

River at Purcell, Indian Territory (Oklahoma) to meet

AT&SF crews building south from Kansas.

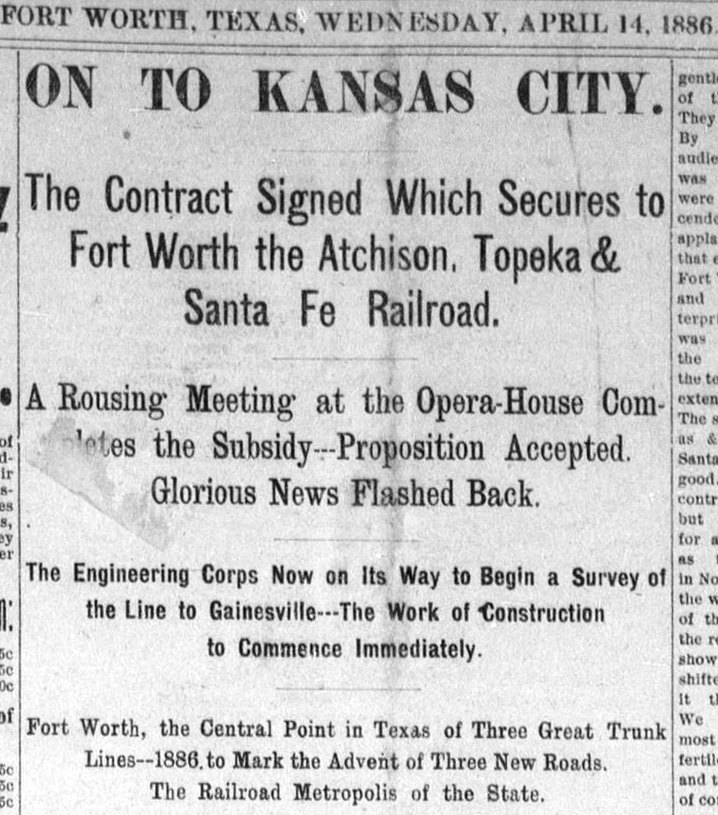

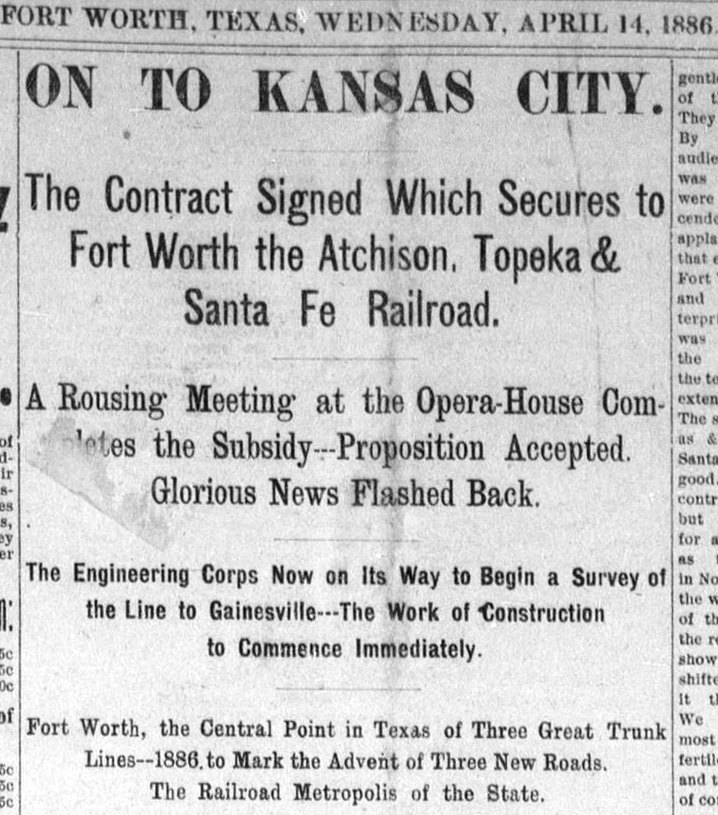

Right and Below:

The Santa Fe deal was BIG news. In the opinion of the Fort Worth Daily Gazette

(April 14, 1886), it made Fort Worth

"The Railroad Metropolis of the State" and

the "Queen City of the Southwest" !

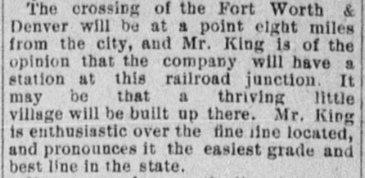

Left:

Santa Fe construction engineer "Mr. King" opines on the crossing of the FW&DC eight miles north

of Ft. Worth. The FW&DC had built through the area four years earlier,

but

if the vicinity had a name, it was not mentioned.

(Fort Worth Daily Gazette, May 25,

1886) |

|

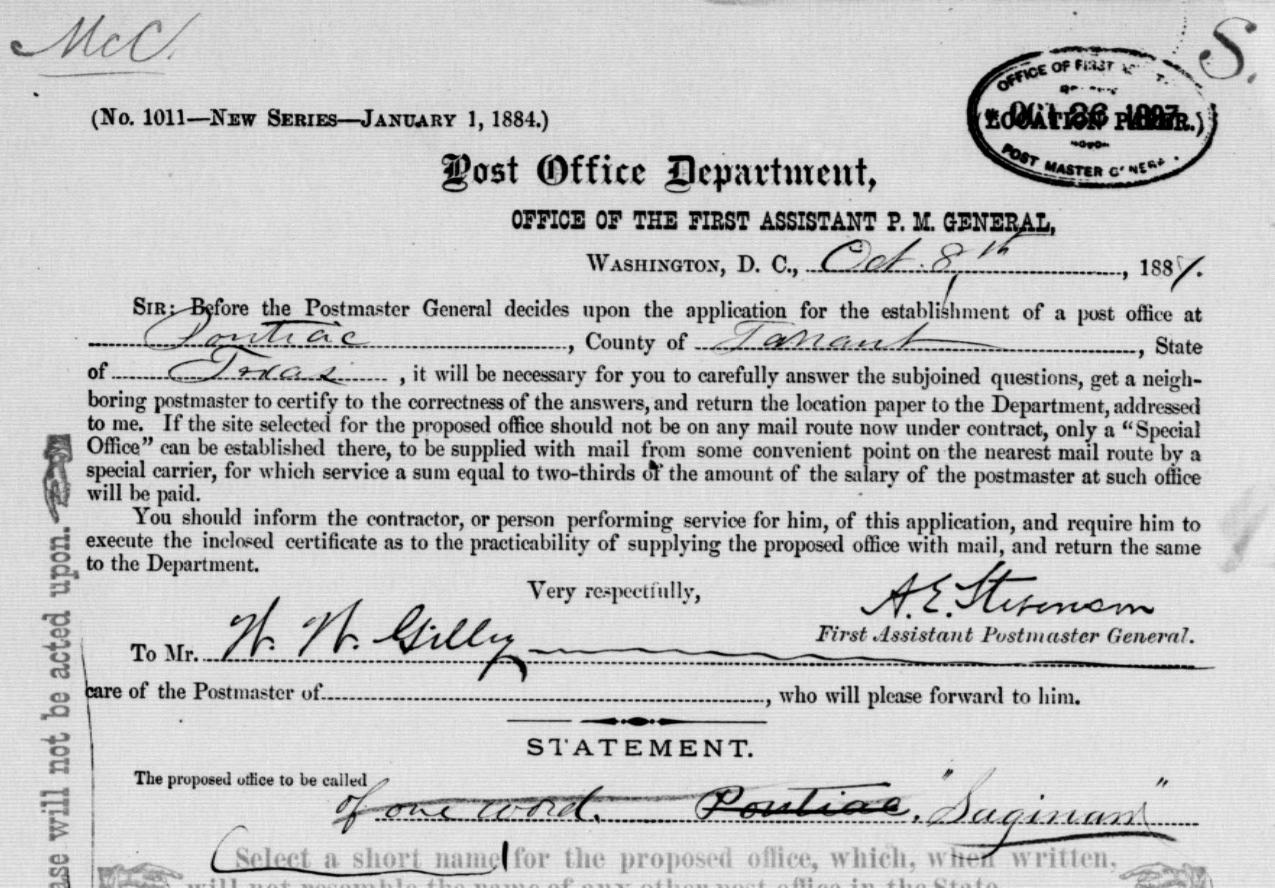

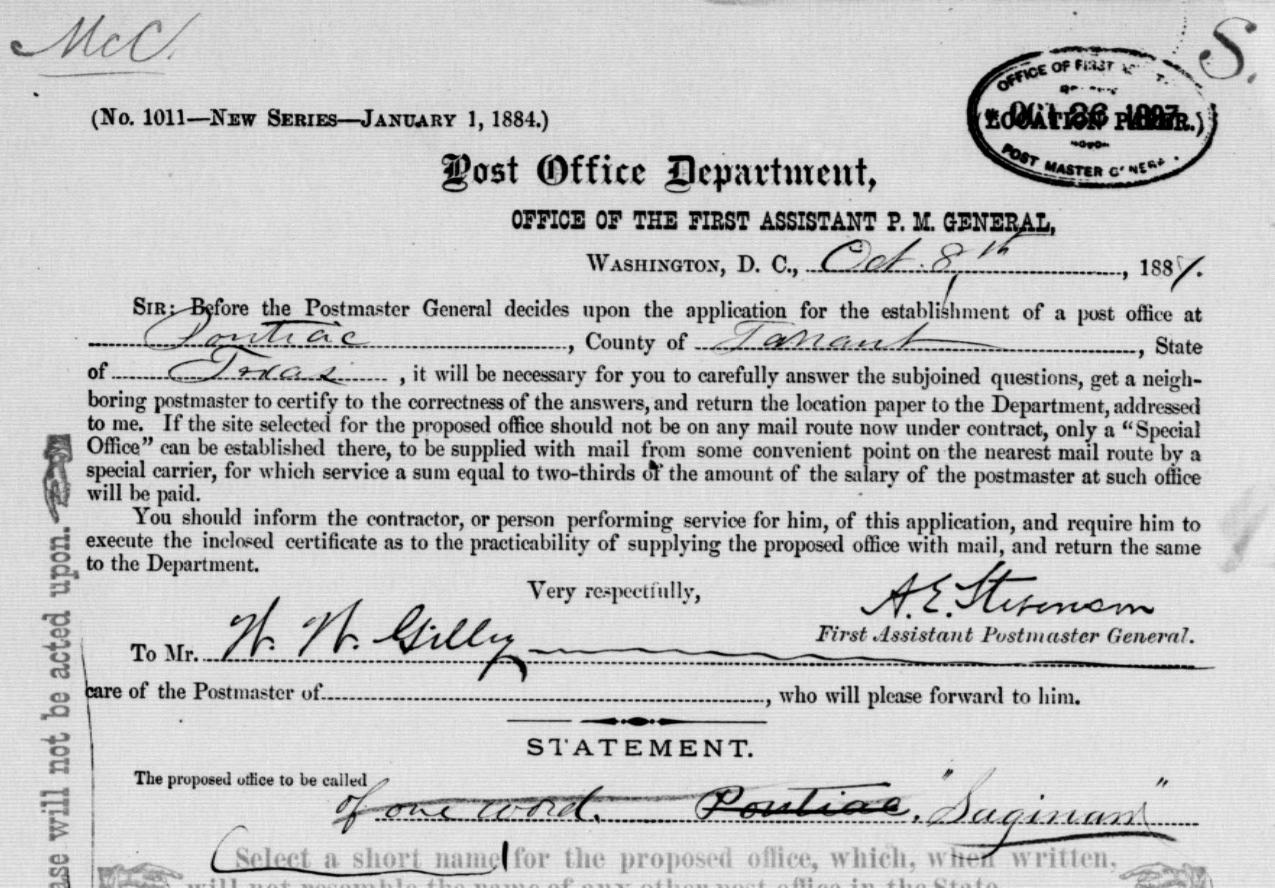

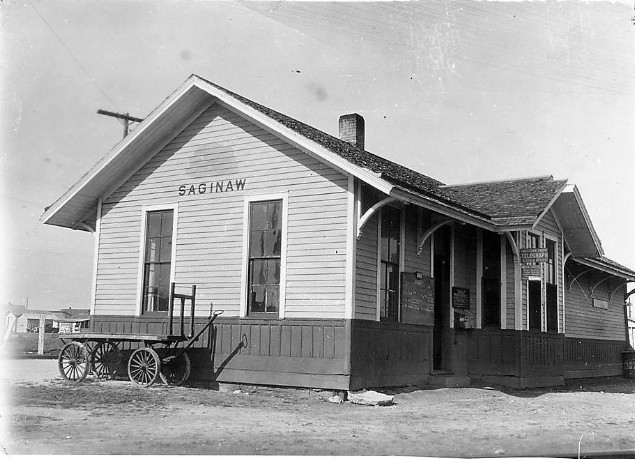

The Texas Historical

Commission asserts that Saginaw was named in 1882

for the Michigan hometown of landowner Jarvis J. Green. Post Office

records paint a more complex picture suggesting that if the 1882 date is

correct, the name Green chose had not been widely adopted. Oddly, it was a

different Michigan town -- "Pontiac" -- selected as the name of the first

Post Office in the area. The request was made to the Post Office Department in

Washington D. C. in late September or early October, 1887 to which officials

responded with an application dated October 8, 1887 (partial image

below.) The application was

filled out and signed on October 11th (mail service was much faster in those

days!) by W. W. Gilley, the proposed Postmaster for Pontiac. The

application states that mail trains were

already stopping at a passenger station

called "Kyley" west of the tracks, 200 ft. from the

proposed Post Office site. The Pontiac Post Office was granted on October 26, 1887,

but did it ever open? On September 6, 1889, a request to change the name to

"Saginaw" was received by the Post Office Department and they responded by

forwarding an application for "re"-establishment, adding a notation... "Send

selection of citizens for re-establishment". This may have been a request for assurances that the change to "Saginaw" was popularly supported by those who had

been using the

Pontiac Post Office, or it may imply that the Pontiac Post Office had gone

dormant or was never built. The application was

completed and signed by the proposed Postmaster, Mattie A. Keith, on

September 23rd. When the name change to Saginaw was granted on October 28th,

Post Office officials went back to the earlier application and wrote "Saginaw",

crossing out "Pontiac".

The impetus for the change from Pontiac to Saginaw, two Michigan towns 78 miles

apart, remains a mystery. Kyley was most likely a temporary name given

to a new passenger station (probably built by Santa Fe) at the crossing. No

Postal records have been found to indicate that Kyley was ever granted a Post Office, but there might have been procedures, formal or

informal, to drop off and accept mail during stops at stations that were not

served by a local Post Office. The

Texas Almanac reports

that Kyley was located in Tarrant County, but provides no additional

information, and no other references to Kyley have been found. (applications from microfilm, courtesy

National Archives)

In 1892, the Chicago, Rock Island &

Texas (CRI&T) Railway was chartered as a Texas-based subsidiary of the Chicago,

Rock Island & Pacific (CRI&P). Rock Island was a major carrier in the Midwest

and Plains states, and the CRI&T was needed for compliance with Texas' railroad

ownership law to take legal possession of tracks coming south from Indian

Territory. By charter, the CRI&T's original target was Weatherford, 27 miles

west of Fort Worth. The rails came south across the Red River near Ringgold,

Texas and proceeded generally

south, crossing the FW&DC at Bowie and continuing

to Bridgeport on a direct

heading to Weatherford, 32 miles beyond. The line to Weatherford

was never completed; instead, the charter was amended in 1893 to authorize

construction to Fort Worth. Track-laying out of Bridgeport proceeded southeast,

crossing the GC&SF at Saginaw but remaining parallel to the FW&DC. Rock Island tracks reached Fort Worth on August 1, 1893.

|

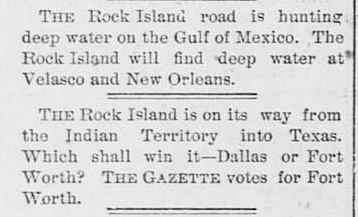

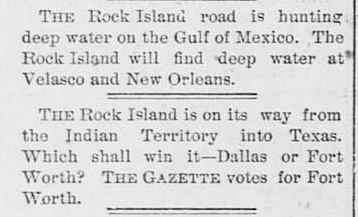

Left:

Cheerleading for their community, a prime responsibility of early Texas

newspapers, the Fort

Worth Gazette of March 5, 1892 speculated on the Rock

Island's plans, including the Texas port of

Velasco as a possible destination.

Right:

On March 24, 1882, the Fort Worth Gazette

reported on Fort Worth businesses hired to perform grading

work for the Rock Island at Bowie, about sixty miles northwest of Fort

Worth. The newspaper comments that the route "...can't

long be kept from the public." The charter bill had already been passed

into law, but for competitive reasons, railroads didn't always specify

their complete plans in the charter, preferring to amend it once their construction

strategy was fully developed. |

|

Why was Weatherford the initial target? As noted by the

Fort Worth Gazette, Rock Island was "hunting

deep water on the Gulf of Mexico", and the GC&SF branch line from

Weatherford to Cleburne would potentially offer a

faster way to reach the GC&SF main line to Galveston compared to routing freight through the complex and

crowded rail network in Fort Worth. But Fort Worth was about five or six times

larger in population than Weatherford, and Dallas, more populous than Ft. Worth,

was farther east. Perhaps Rock Island simply hadn't decided on its final

strategy but wanted to get started with construction to avoid completely missing

out on Texas opportunities. In

A History of the Texas Railroads, Reed

acknowledges the plan to build to Weatherford and the subsequent decision to

redirect the line to Fort Worth, but he offers no insight on the underlying

rationale for either decision. It seems unlikely, but it is at least possible that Weatherford was

simply a

misdirection all along, for both competitive and financial (land acquisition) reasons. Allowing the entire route to be

publicly known would have given plenty of time for the other railroads to adjust

their development plans to counter Rock Island's entry into Ft. Worth.

|

|

To control the Saginaw crossing, Tower 29 was

authorized by the Railroad Commission of Texas (RCT) to commence

operations on October 21, 1903 (RCT had ordered an earlier completion

date, but an extension was granted in August.) The mechanical

interlocking plant was built by Union Switch & Signal Co. with 32

functions spread over 30 "armstrong" levers. The three railroads that

shared Tower 29's expenses were the FW&DC, the GC&SF, and a new

railroad, the Chicago, Rock Island & Gulf. It had been chartered 18

months earlier to build from Ft. Worth to Dallas, but the charter also

consolidated all of Rock Island's Texas subsidiaries (the CRI&T and two

others.) Because the rails at Saginaw predated the 1901 state law

authorizing RCT to regulate railroad crossings, the capital expense for

the tower and interlocking plant would have been shared equally by the

three railroads. The tower's recurring expenses for operation and

maintenance would have been split based on the percentage of the

interlocker's total functions allocated to each railroad; the allocation for Tower 29 has not been determined.

Left:

Tower 29 interior photos from 1981, courtesy of Con Sweet |

Information published by RCT in 1916 (and annually

thereafter) showed that Rock Island had been given responsibility for operating

and maintaining Tower 29. While this would imply, but not guarantee, that Rock

Island had also been responsible for the design and construction of the tower,

Rock Island left no doubt by advertising the tower's heritage with "Rock Island" painted on the

exterior, at least in later years. Former Rock Island locomotive engineer Joe Rayburn comments:

The sign on the south face of the tower has

either faded or been touched up, but there was a Rock Island emblem there. Being

a Rock Island tower, it was operated by RI personnel. I've been up in it many

times when being held there for congestion. The Operator that worked the tower

had phone access to all three Dispatchers ... RI, Santa Fe, and FWD ... and he

handled and delivered train orders to all three railroads.

RCT's annual interlocker summary

published at the end of 1916 reported Tower 29 having 30 total functions, and this value remained

steady through 1922. For the next four years, 1923 through 1926, RCT's published

data for Tower 29 looks suspicious, as if a typesetting error was inadvertently

propagated each year. The 1923 table showed Tower 29 with 37 functions, identical to the count for next tower in the list,

Tower 30 at Harrisburg (which had been listed with 33 functions in 1922.)

Towers 29 and 30 then remained in lock step with 37 functions in 1924 and 1925,

and 45 functions in 1926. In 1927, Tower 29 reverted to 37 functions but Tower

30 remained at 45 -- as if the error had been discovered, but with the

assumption that it had first occurred in 1926. In 1928, Tower 29 dropped again,

to 25 functions, while Tower 30 remained at 45. It's certainly possible that

this was random coincidence, but if so, then 35 function count changes were

implemented over a six year span at Tower 29. It seems more probable that the 37 and 45

counts were misprints associated with Tower 30's adjacent entry, i.e. Tower 29

most likely remained at 30 functions until the reduction to 25 occurred in 1928.

As the mechanical interlocking plant would have been 25 years old in 1928, it's

possible that the reduction to 25 functions stemmed from the installation of a

newer plant, with some functions being consolidated into single levers by the new design.

Tower 29 remained in service even as the railroads it served went

through changes. The FW&DC dropped "City" from its name in 1951,

becoming simply the FW&D, by then a wholly-owned subsidiary of the C&S.

The C&S was merged into Burlington Northern (BN) in 1981, and the FW&D

lost its separate identity in 1982, becoming a BN operation. When Rock

Island went out of business in the spring of 1980, its line from

Atchison, Kansas to Dallas via Saginaw and Ft. Worth began to be

operated by the Oklahoma, Kansas & Texas (OK&T) Railroad, a newly

chartered subsidiary of the Missouri - Kansas - Texas (MKT) Railroad

(the 1923 successor created to exit the bankruptcy of the former MK&T.)

When the OK&T was unable to agree on a purchase price with Rock Island's

bankruptcy trustee, it was forced to suspend service at the end of 1981.

A newly formed company, the North Central Texas Railway, began operating

the tracks between Dallas and Chico, Texas, seven miles north of

Bridgeport, where a rail-served

limestone quarry had long been in operation.

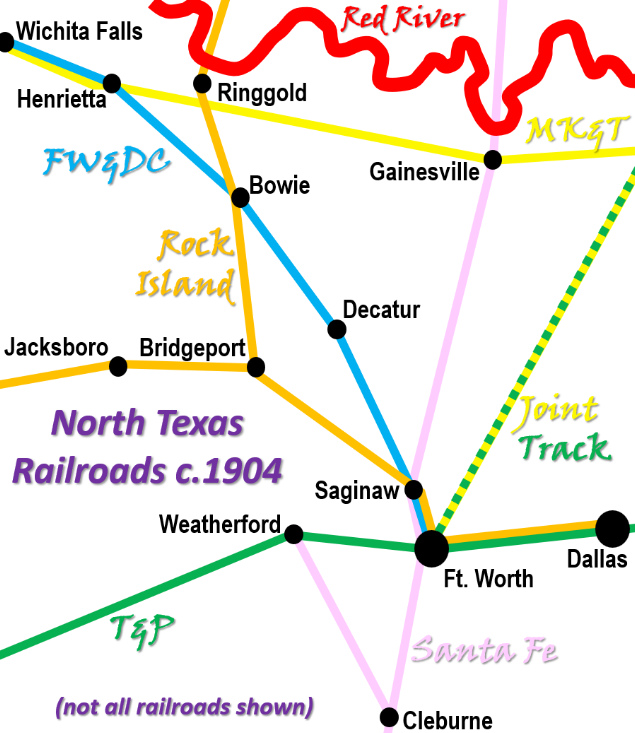

Right: area map of

North Texas Railroads c.1904 (not all railroads shown) For access to

the Port of Galveston using a Santa Fe exchange, the geography supported Rock

Island's potential interest in building straight south from the Red

River to Weatherford as an efficient route to Cleburne. Going

directly to Ft. Worth from the river would have essentially duplicated

much of the FW&DC route, creating a more competitive

situation for local traffic. Also, Bridgeport was able to serve as a Rock Island branch

point to the west where coal and other minerals were being mined,

eventually becoming a major oil producing region. Rock Island built 28

miles west from Bridgeport to Jacksboro in 1899, continuing 27 miles

farther west to Graham in 1903.

|

|

With assistance from the State of Oklahoma, the OK&T was

finally able to complete the purchase of the Rock Island tracks as far north as

Salina, Kansas and resume service in November, 1982. Precisely how Tower 29's

operations were sustained during Rock Island's bankruptcy has not been

determined, but it appears likely that BN took over the responsibility. BN and

Rock Island had worked together for decades sharing a main track between Dallas

and Houston, and with Rock Island's demise, BN took over full operation of that line. Regardless

of how it was staffed and maintained, Tower 29 didn't last much longer; it was razed in early 1986. Willie Kirby

recalls...

"I had the job of removing the equipment in Tower 29.

The Order board on the Rock Island went to the Texas State Railroad

and I have the two order board levers with "North"

& "South" marked on them. The Texas State RR got a lot of

the equipment. When I finished the removal part, the Burlington

Northern Railroad sent a person out to burn the tower down. Somebody

beat me to the "scissor phone". It was about 1985 or

1986 when I completed the job."

In 1988, Union Pacific (UP) was authorized by the

Interstate Commerce Commission to acquire the MKT, and it was merged into UP's

Missouri Pacific (MP) subsidiary in late 1989. UP consolidated its various

railroad subsidiaries under the UP name at the beginning of 1997, and UP trains

continue to operate through Saginaw on what is now known as UP's Duncan

Subdivision. At the end of 1996, BN merged with AT&SF to create Burlington

Northern Santa Fe (BNSF), accounting for the other two rail lines through

Saginaw. Trains on BNSF's Fort Worth Subdivision (former AT&SF) and Wichita

Falls Subdivision (former FW&D) continue to operate through Saginaw. In the summer of 2023, UP and BNSF restructured the track topology at

Saginaw to eliminate the crossing diamonds, replacing them with multiple

switches.

Right: This 1963 aerial image ((c)

historicaerials.com) of Tower 29 and its immediate vicinity has been

annotated to identify the main lines. The Rock Island (orange

arrows) and FW&D (blue arrows) tracks remained generally parallel past

Tower 29 (orange rectangle.) The Santa Fe main line (pink arrows) crossed these two

railroads at diamonds approximately 250 ft. apart. The north diamond

(yellow circle) was the FW&D crossing; the south diamond (green circle)

was the Rock Island crossing. Note the railcars sitting on connecting

tracks and industry spurs nearby. In the 1980s, the FW&D was double-tracked

past the tower, adding yet a third diamond to the topology.

Below: close-up of the

Tower 29 diamonds from December, 2019 (Google Earth)

|

|

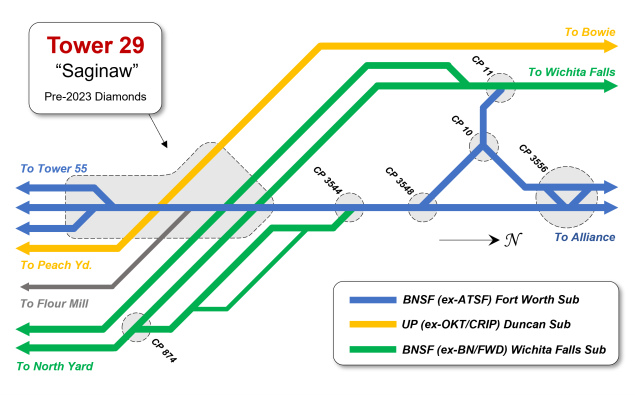

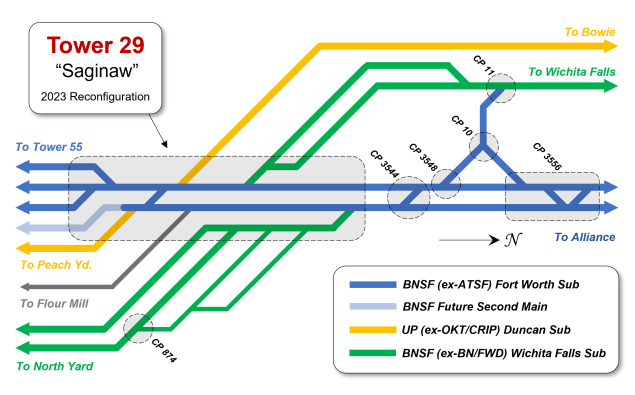

Summer 2023 Construction at Tower 29

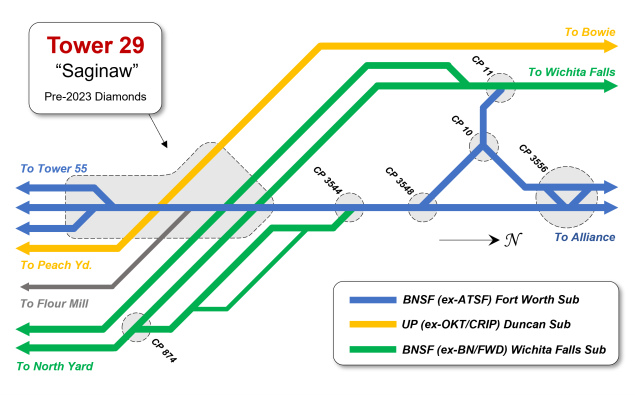

Above Left:

This track chart (with North to the right) illustrates the traditional track topology at Tower 29

("traditional" in the recent sense because it shows the double track on the

BNSF Wichita Falls Subdivision, an extra track that the "original" FW&DC did not have

at the time Tower 29 was commissioned.) The reference to

"Alliance" is for Alliance Yard, a major BNSF yard in southern Denton

County opened by AT&SF in 1994, shortly before the BNSF merger.

Tower 55 is the original major rail

junction in Ft. Worth, near downtown. Bowie

is the site of Tower 1, where the Rock Island crossed the FW&DC between Ft. Worth and Wichita

Falls. Peach Yard is a former Rock Island yard a mile north of

Purina Jct. North Yard is the original FW&DC yard immediately north

of Hodge. The Flour Mill track

leads to Saginaw Mill, now a facility of Ardent Mills. It was opened in 1932 by Burrus Mill and Elevator Co., the sponsor and

broadcast location for the

Light

Crust Doughboys, a popular western swing band on Texas radio in the

1930s that helped launch the career of Texas music legend

Bob Wills.

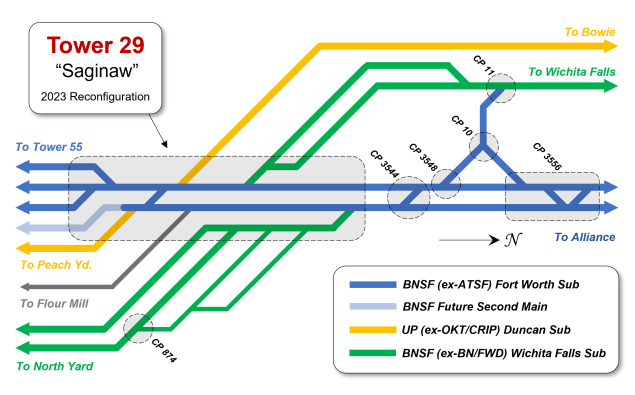

Above Right: This track

chart (with North to the right) shows the changes that were implemented in the

summer of 2023. The double-tracking of BNSF's Fort Worth Subdivision motivated

the decision to restructure the junction to eliminate the crossing diamonds.

From the south, the UP Duncan Subdivision merges into the new (east)

double-track on the Fort Worth Subdivision; a crossover carries UP trains

to the west track and a switch that leads to UP's line to Bowie. BNSF's Wichita

Falls Subdivision is now split by the removal of the diamonds. Instead of

crossing over, southbound movements merge onto the west track of the Fort Worth

Subdivision while northbound movements merge onto the new east track. A crossover between the east and west tracks

at CP 3544 facilitates

movements to and from the Wichita Falls Subdivision via CP 10 / CP 11. Special

thanks to BNSF Engineer Jeff Ford for producing these track charts! Jeff adds

these comments regarding potential operational changes...

The route between North Yard

and Wichita Falls has been via the wye connection (CP 10/11). They've

deliberately installed turnouts to support 30 mph through such a route. I'm not

sure how much traffic they're sending in/out of North Yard via Wichita Falls

these days, so a "shift" in traffic is probably a fair statement. Also, by the

same token, coal trains will no longer need to route via the wye, so they

actually can glide on/off the old FW&D and off/on the Santa Fe at the

interlocker with a less roundabout routing.

Above Left: This view looks north along BNSF's Fort

Worth Subdivision where the double-track Wichita Falls Subdivision now switches

off (left) to the northwest. Previously, the Wichita Falls Subdivision crossed

here. Above Right: Looking

southeast along the Wichita Falls Subdivision from McElroy Blvd., the tracks no

longer cross the Fort Worth Subdivision. Instead, they curve south and merge

onto it. Below Left: This

image faces north from E. Industrial Ave. along UP's Duncan Subdivision. In the

distance, the

track previously made a slight curve to the northwest (left) to cross the Fort Worth

Subdivision. Now, a more abrupt curve is implemented to bring UP's tracks

westward (left) to merge onto the Fort Worth Subdivision.

Below Right: From the opposite

direction, facing southeast at McElroy Blvd., UP's Duncan Subdivision previously

crossed BNSF's Fort Worth Subdivision straight ahead and then curved south. Now,

the crossing is eliminated and UP's tracks curve south to merge onto the Fort Worth

Subdivision. Southbound UP trains will then take a crossover and a new switch

that will move them back onto the Duncan Subdivision. (all four photos by Mike

Murray, July/August 2023)

As the town grew, railroads were an ever-present component of

life in Saginaw. The mills and elevators, served by rail, employed many

townspeople. As the main highway through town evolved to become U.S. Highway

287, it provided direct views of rail operations for miles, serving as a virtual

boundary dividing Saginaw into industrial and residential zones (though that is

no longer the case; Saginaw "jumped the tracks" and began developing east of the

railroads as Ft. Worth residents spilled out into the suburbs in ever-increasing

numbers.) The proximity of the tracks to U.S. 287 and the wide

open views of railroading from the highway made Tower 29 a frequent target for

photographers. It could easily be the most photographed among all Texas

interlocking towers.

Right:

In 2000, the former Houston & Texas Central Railway passenger depot from

Kosse was placed trackside along U.S. 287, very close to the former site

of Tower 29. The depot now houses the Saginaw Chamber of Commerce, and

the adjacent parking lot has become a popular location for watching

trains.

The North Texas Chapter of the National Railway

Historical Society hosts an annual train-watching event each May, "24

Hours at Saginaw", at the Chamber of Commerce facility. What would

have been the 17th annual event in 2023 was cancelled due to the rail

traffic impact of the aforementioned construction activities removing

the Tower 29 crossing diamonds. An alternate event was planned for

September at Big Sandy. (Bob King photo,

January, 2016) |

|

Above Left: east

face of the tower in April, 1983

Above Right: west

face of the tower in November, 1978 (both photos by Myron Malone)

Below Left:

undated photo, collection of

Mark Nerren Below Right:

Tom Hoffman collection, June, 1969 (hat tip, Chino Chapa)

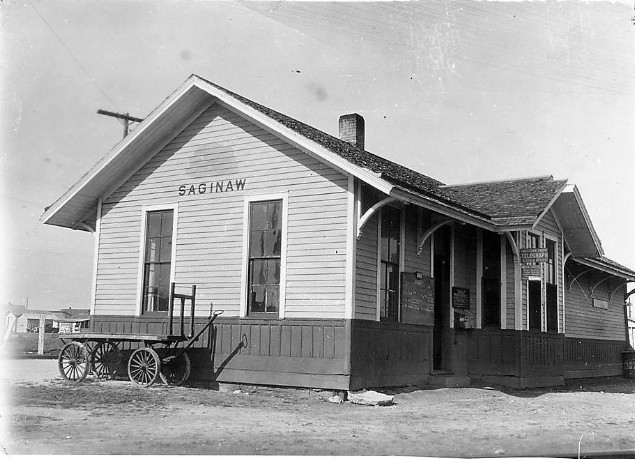

Above Left: Union Depot at

Saginaw, 1931 (Kansas State Historical Society, hat tip Chino Chapa)

Above Right: Tower 29 c. 1982

(Michael North photo)

Above Left: A northbound Rock

Island freight passes Tower 29 as a Santa Fe freight waits in the distance.

(photo by J. Parker Lamb, August, 1964, (c)2016, Center for Railroad Photography

and Art) Above Right: There

are ominous clouds to the south in this view down the Santa Fe tracks from the

1970s (J. F. Shelton photo) Below:

two photos of the abandoned tower taken by Robert Carter on January 4, 1986

Above: This local news video from

1976 discusses operations at Tower 29 as the last manually operated interlocker

in Texas.