Texas Railroad History - Tower 17 - Rosenberg

A Crossing of the Galveston, Harrisburg & San

Antonio Railway and the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe Railway

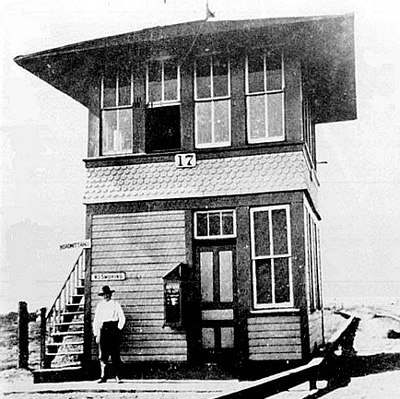

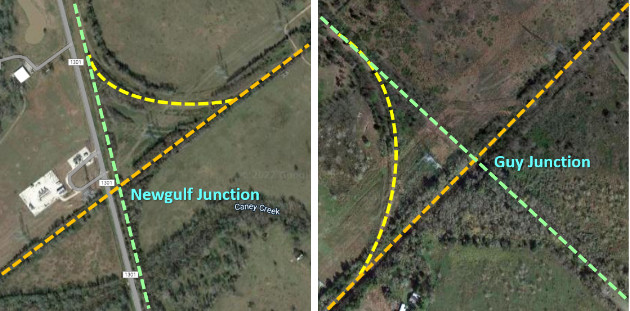

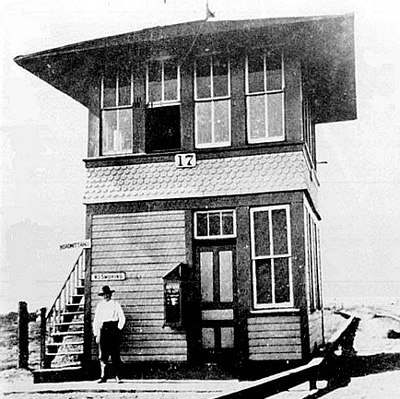

Above Left:

This photo shows the east face of the original Tower 17

as it appeared in 1907. The gentleman in the photo is C.C. Harris

who was employed as a towerman. (Rosenberg Railroad

Museum courtesy of Ken Stavinoha) Above

Right: Tower 17 was enlarged in the 1950's when additional

operators were moved from the Rosenberg depot to the tower. The ground floor

door and window on the east face remain in the same position as in the 1907

photo, but the tower has been expanded on the south side, necessitating removal

and redesign of the staircase. The Queen Anne style "fish scale" pattern between

the floors (common to SP towers, e.g. Tower 16) is

the same as in the 1907 photo but appears only beneath the original four

windows. (Jim King photo c.1997)

Above:

George Werner took this photo of an eastbound Southern Pacific train crossing

the diamond on January 4, 1969 (from Southern

Pacific's Eastern Lines 1946-1996, D. M. Bernstein, 2015)

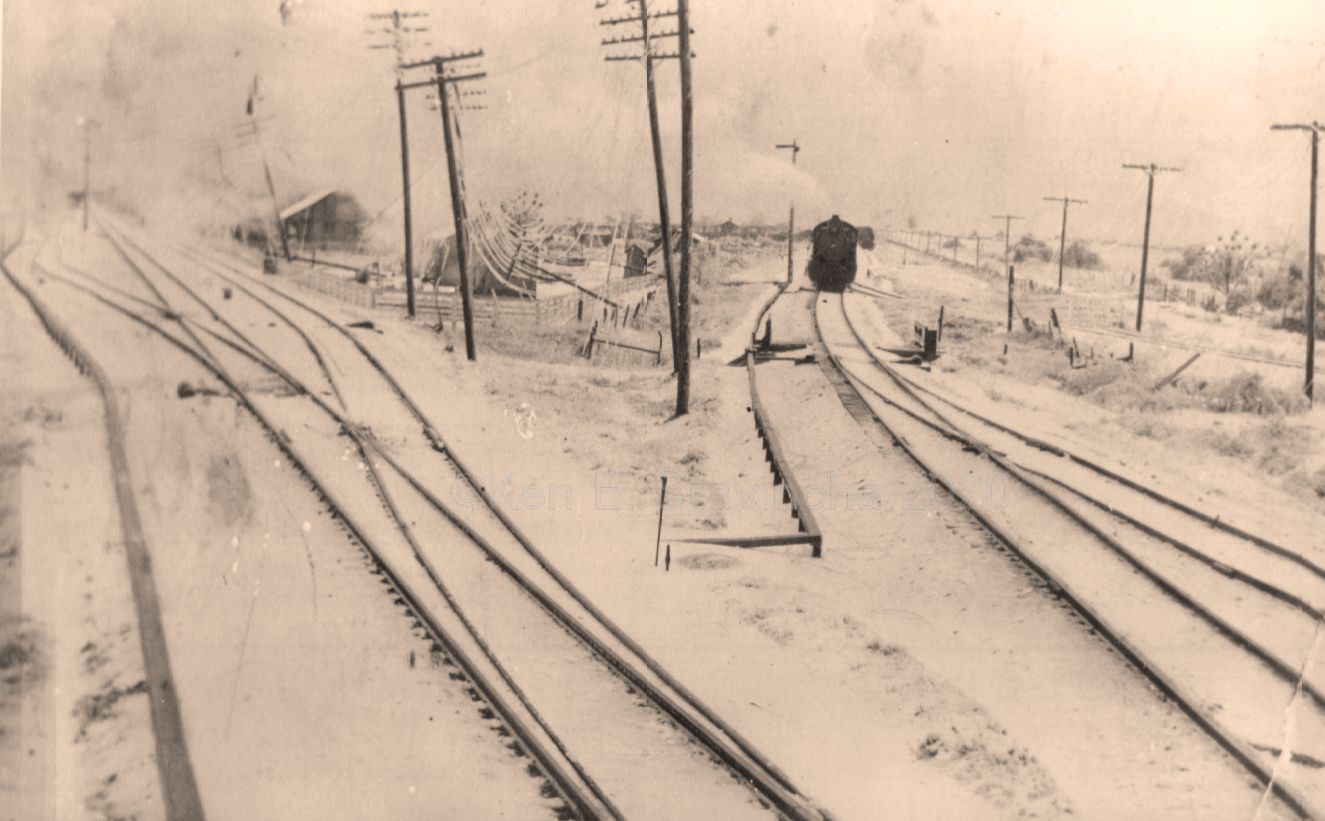

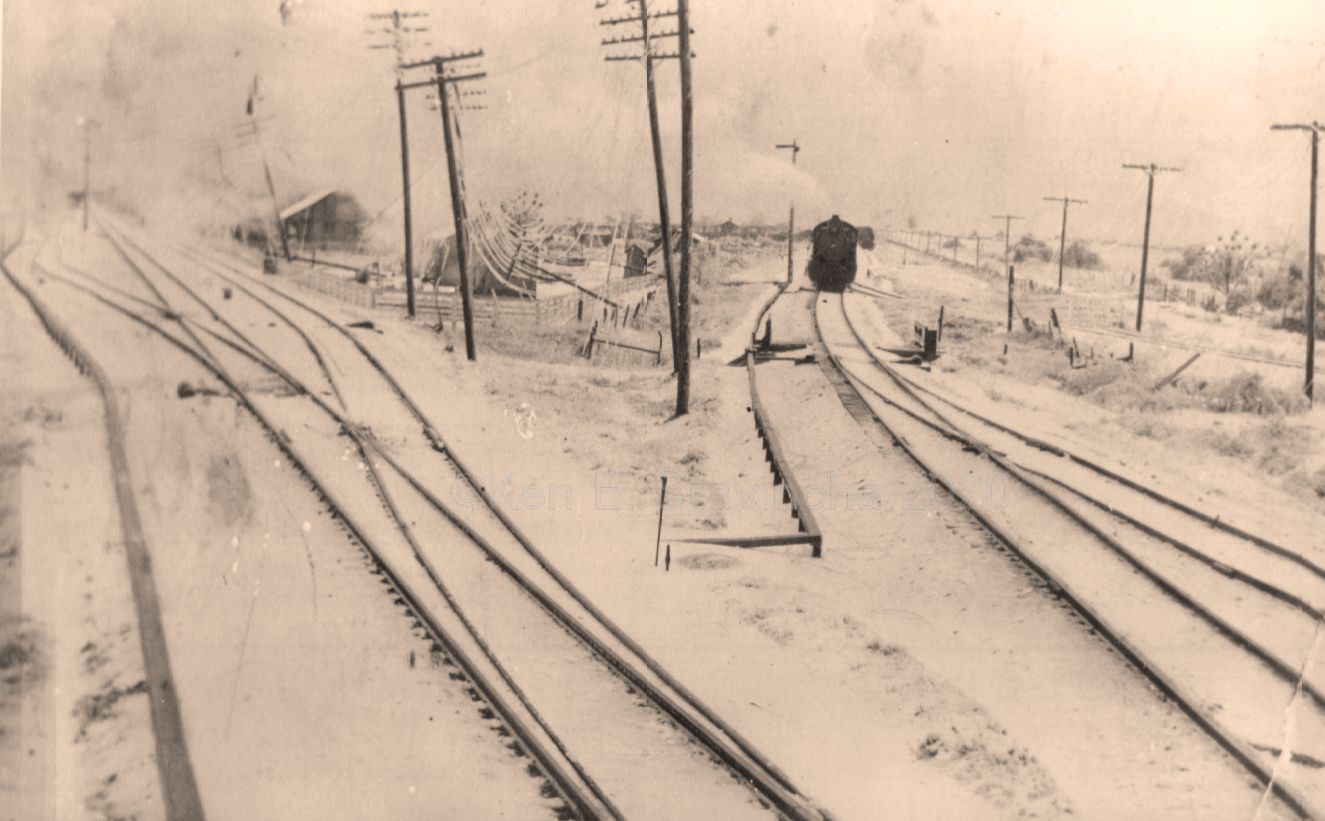

Below: This undated photo was

taken facing northwest from a window of Tower 17 during a rare winter storm.

Informed speculation suggests December, 1924 as a possible date. It shows a

southbound Santa Fe train waiting near a downed utility pole with ice-covered

wires. (Ken Stavinoha collection)

The town of Rosenberg was

founded when the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe (GC&SF) Railway built through

the coastal prairie southwest of Houston in 1879, crossing

the rail line of the Galveston, Harrisburg and San Antonio (GH&SA) Railway three

miles west of Richmond. The GH&SA tracks had been there for more than two

decades, originally as the Buffalo Bayou, Brazos

and Colorado (BBB&C) Railway, the first railroad in Texas, chartered several years before

the Civil War. The BBB&C had begun at

Harrisburg on Buffalo Bayou southeast

of Houston and had laid twenty miles of track west to Stafford's

Point in 1853. By 1855, twelve additional miles had been built to Richmond, the county

seat of Fort Bend County. Reaching Richmond, on the west bank of the Brazos

River, required the BBB&C's first major river crossing. By 1860, tracks

had been laid 48 miles farther west to the tiny community of Alleyton, three

miles east of the Colorado River, a river the BBB&C did not plan to cross.

Instead, the BBB&C charter called for the railroad to remain east of the

Colorado and

follow the river north to La Grange and Austin. Columbus, three miles farther west on the opposite bank of the river, was

determined to obtain railroad service given the proximity of the BBB&C tracks. Its citizens chartered

the Columbus Tap Railroad to build from Alleyton to the river and bridge it into Columbus, but the outbreak of the Civil War delayed those plans. After the

War, the tracks were built from Alleyton to the east bank of the river and a

ferry was used to move goods and passengers across it. In 1866, the Legislature

gave the BBB&C authorization to buy the Columbus Tap, but the Tap retained its

separate legal existence, likely due to the BBB&C's impending default. Post-war economic conditions

had left

the BBB&C unable to make payments on its construction contract. As a result,

an 1867 court

judgment awarded the BBB&C to the contractor, William Sledge.

Sledge

was stuck with the BBB&C so he tried to make something of it. A newspaper

article in the La Grange States Rights Democrat

of May 24, 1867 reports the details of a meeting Sledge attended six days

earlier to discuss the BBB&C's plans to resume construction toward La Grange.

The article notes "The cost of the bridge now being built at Columbus was an

affair undertaken by the people of Columbus and Colorado County, and the

building of the bridge above Columbus it was desirable should be undertaken by

the people of La Grange and Fayette County." The significance of this

article and this specific passage is that the Colorado River bridge for the

BBB&C was already in progress and was being funded by citizens of Columbus. The

backers were likely the same people who had chartered the Columbus Tap. Columbus

was the county seat of Colorado County, definitely worthy of rail service once

the bridge was finished. But rather than make it a "tap spur" from Alleyton as the

Columbus Tap had envisioned, the BBB&C preferred to operate through Columbus and

then turn north and cross the Colorado River again to get back to the surveyed

route to La Grange. This explains the need for a "...bridge above

Columbus...", hopefully to be funded by "...the citizens of La Grange

and Fayette County..." If Columbus was served by the BBB&C on a through

route, a second bridge over the Colorado would be required

somewhere because La Grange sits entirely on

the opposite bank of the river from Columbus.

Sledge

was stuck with the BBB&C so he tried to make something of it. A newspaper

article in the La Grange States Rights Democrat

of May 24, 1867 reports the details of a meeting Sledge attended six days

earlier to discuss the BBB&C's plans to resume construction toward La Grange.

The article notes "The cost of the bridge now being built at Columbus was an

affair undertaken by the people of Columbus and Colorado County, and the

building of the bridge above Columbus it was desirable should be undertaken by

the people of La Grange and Fayette County." The significance of this

article and this specific passage is that the Colorado River bridge for the

BBB&C was already in progress and was being funded by citizens of Columbus. The

backers were likely the same people who had chartered the Columbus Tap. Columbus

was the county seat of Colorado County, definitely worthy of rail service once

the bridge was finished. But rather than make it a "tap spur" from Alleyton as the

Columbus Tap had envisioned, the BBB&C preferred to operate through Columbus and

then turn north and cross the Colorado River again to get back to the surveyed

route to La Grange. This explains the need for a "...bridge above

Columbus...", hopefully to be funded by "...the citizens of La Grange

and Fayette County..." If Columbus was served by the BBB&C on a through

route, a second bridge over the Colorado would be required

somewhere because La Grange sits entirely on

the opposite bank of the river from Columbus.

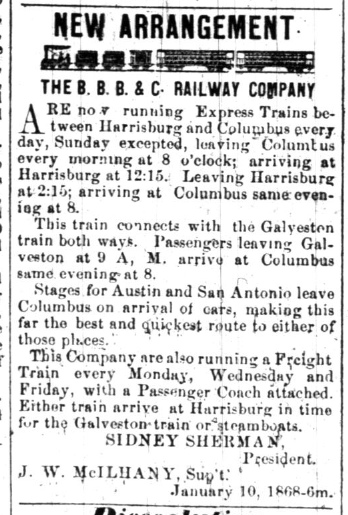

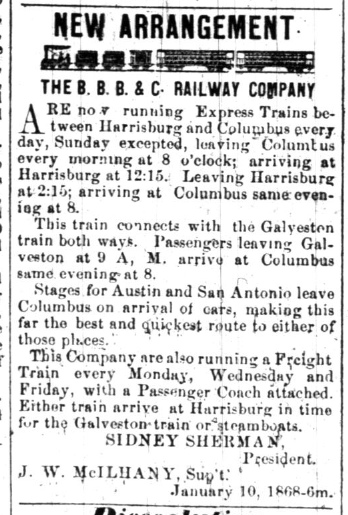

Left: The BBB&C bridge into

Columbus was apparently completed sometime later in 1867 because the

La Grange States Rights Democrat of January

10, 1868 carried this advertisement announcing new BBB&C Express Trains between

Harrisburg and Columbus. Note that "Stages for Austin and San Antonio leave

Columbus on arrival of cars..." Both of those towns lacked rail service, but a

western extension of the tracks at Brenham was

already being seriously contemplated for Austin, which would see its first train in December, 1871.

San Antonio also lacked rail service and, as the second largest city in Texas,

was desperate to obtain it. With the BBB&C committed to building north out of

Columbus to La Grange, there was extensive (but ultimately non-productive)

activity in San Antonio to sponsor a railroad to Columbus to intersect with the

BBB&C.

Although Sledge carried on and tried to generate revenue from

his railroad, Thomas Peirce had bigger and better ideas for it. Peirce (with the unusual ei spelling of his

last name) was a wealthy Boston businessman, lawyer and landowner (including a

large sugar plantation near Arcola.) He had done legal work for the BBB&C before

the War, so he was familiar with it. Peirce formed an investor group for the

purpose of acquiring the railroad from Sledge; Sledge agreed to the sale in

1870. The BBB&C was not in great shape, so Peirce rehabilitated it and improved

its operations. This was essential to set a reputation going forward. Peirce had

a vision of what he wanted to do, and like all wealthy businessmen, he planned

do it with other people's money. But investors would not sink money into his

larger vision if the railroad couldn't manage its existing operations.

Peirce and his investors eventually petitioned the

Legislature to modify the BBB&C's charter to authorize Peirce to implement

his plan,

which was...building to

San Antonio instead of to La Grange and Austin. The

citizens of La Grange protested, so the Legislature granted the request to build

to San Antonio but retained a requirement to build

a branch line to La Grange (which Peirce eventually fulfilled in 1881.) The

revised charter also allowed the railroad to connect with

any railroad to the Pacific (an innocuous provision that proved to have a

profound impact.) The railroad's name was also revised; it

would be the Galveston, Harrisburg and San Antonio (GH&SA) Railway. Peirce

bought out most of the other investors and initiated construction west from Columbus toward San Antonio,

reaching Luling, 71 miles from Columbus, by the end

of 1874. As part

of his efforts to

publicize his westward march toward San Antonio, Peirce coined the term "Sunset

Route", a name that remains familiar to every

railroader today, nearly 150 years later. As Columbus was roughly halfway

between Harrisburg and San Antonio, the GH&SA established a maintenance base on

the west outskirts of town in 1885. The community that grew up around it, known

as Glidden, remains unincorporated, but continues to provide the name for the

rail segment of the Sunset Route between San Antonio and Harrisburg, known as the Glidden

Subdivision, now operated by Union Pacific (UP).

The GH&SA's rails reached San Antonio

in 1877, and within a year, Peirce and Southern Pacific (SP) Chairman Collis

Huntington were discussing a potential partnership. SP was building east from

California to Yuma, Arizona. Huntington had decided they would continue past

Yuma all the way to El Paso, and he had obtained

permission from the territorial governments of Arizona and New Mexico to do so.

Huntington wanted to create a southern transcontinental route close to Mexico

via El Paso and San Antonio, while also serving Gulf ports at Houston and New

Orleans. This required building 800 miles across Texas, but SP did not have a

charter from the State of Texas. The chances of getting one anytime soon were

poor; the other major railroads in Texas would fight it vigorously in the

Legislature. Hence, Huntington's attention turned to the GH&SA for obvious

reasons. The GH&SA

did have a state charter that already authorized

construction to connect with any Pacific railroad, and it

did have a rail line covering part of the distance between El Paso and

Houston. It also had rights to operate into downtown Houston on the

International & Great Northern (I&GN) from Pierce Junction

(which had been Peirce Junction until the Post Office forced a spelling

change!) The GH&SA had everything Huntington needed except tracks between

San Antonio and El

Paso.

Building to El Paso would be a significant financial undertaking

for Peirce, but Huntington wanted to act fast; he needed to have a route between

El Paso and Houston in place by the time SP reached El Paso from Yuma. His

solution was to have SP finance the entire job for the GH&SA, with construction

teams building from both directions to meet in the middle. Both men understood

that by loaning the funds, SP would hold substantial GH&SA debt and be

well-positioned to acquire it outright, yet Peirce was agreeable. At age 60, he

had already surpassed life expectancy for that era, he couldn't run the GH&SA

forever, and he could ensure its long term viability by partnering with SP. By

the summer of 1880, an agreement between the two men was in place and SP survey

crews were sent to Texas to map the route. Peirce contracted with SP's Southern

Development Co. to field construction forces working east from El Paso. Their

work began in June, 1881 on behalf of the GH&SA while Peirce's own construction forces built west from San Antonio. After a

bit more than a year and a half, the two

railroads met at the Pecos River on January 12, 1883, where

Huntington and Peirce drove a Silver Spike signifying completion of a major

portion of a southern transcontinental

rail line. [It was not the southern transcontinental

rail line because the Texas & Pacific (T&P) Railway, controlled by rail

baron Jay Gould, was building west from Texarkana

to San Diego under a national charter granted by Congress. The T&P had been significantly delayed by financial issues;

construction had finally proceeded west of

Ft. Worth but it was still a long ways from El Paso. As SP began building east

from El Paso on behalf of the GH&SA, Gould realized he had little choice but to compromise with

Huntington.]

As SP trains began operating to Houston, SP leased the GH&SA for several years and ultimately acquired it.

Less than three years after the Silver Spike ceremony, Peirce died at age 67.

In 1875, as GH&SA construction was getting closer to San Antonio, the GC&SF was

just getting started out of Galveston. It had been

chartered in 1873 with a conceptual plan to build from Galveston to the Texas

Panhandle, continuing to Colorado. An unusual provision in the charter allowed the

Galveston County government to buy stock in the railroad, which they did, a half

million dollars worth! This was two-thirds of the issued stock, giving the

Galveston County Commissioners

controlling interest in the railroad should they choose to exercise it. The GC&SF's first step was to build a new

rail bridge from Galveston Island to the mainland at

Virginia Point; it was promptly damaged by a hurricane in September, 1875,

necessitating $25,000 in repairs. From Virginia Point, construction proceeded northwest toward

Richmond. The GH&SA would soon be serving San Antonio, hence the GC&SF envisioned

Richmond as a valuable interchange point for trade between San Antonio and

Galveston, the two largest cities in Texas. Beyond Richmond, the GC&SF would go

northwest, staying between the Brazos and San Bernard

Rivers where they converge to a separation of slightly under four miles at the

narrowest point.

GC&SF

construction from Virginia Point toward Richmond was slow; only

the first 42 miles to Arcola was complete by 1877. But having finally reached

"somewhere", Arcola was promoted as a significant milestone for the GC&SF

because it was also a stop on the I&GN line out of Houston. The GC&SF

decided to advertise its progress (as if reaching Arcola could be counted as

such!) by running a VIP excursion train out of Galveston that went to Arcola,

turned north on the I&GN to

Pierce Junction, and then headed west to Richmond on the GH&SA.

GC&SF

construction from Virginia Point toward Richmond was slow; only

the first 42 miles to Arcola was complete by 1877. But having finally reached

"somewhere", Arcola was promoted as a significant milestone for the GC&SF

because it was also a stop on the I&GN line out of Houston. The GC&SF

decided to advertise its progress (as if reaching Arcola could be counted as

such!) by running a VIP excursion train out of Galveston that went to Arcola,

turned north on the I&GN to

Pierce Junction, and then headed west to Richmond on the GH&SA.

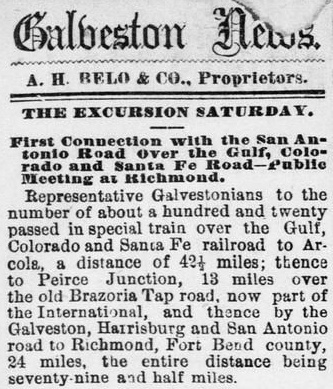

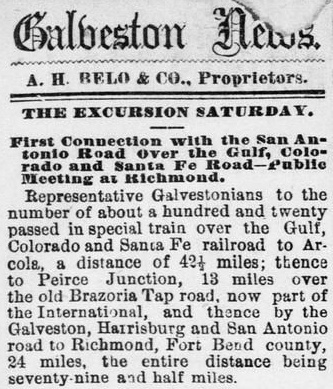

Right:

The lead story in the Galveston Daily News

of April 30, 1878 reported the first excursion train from Galveston to

Richmond via Arcola and Pierce Junction (which the reporter spelled "Peirce"

although the Post Office had changed it two years earlier.)

The

Brazos River was five miles west of Arcola, and bridging it became a significant

problem for the GC&SF, mostly for cash flow reasons. The major problem was that

Galveston County's majority ownership of the company raised novel legal

questions for investors assessing what would happen if the railroad defaulted on bond payments.

Suing the majority owner for

recovery would be impossible; Galveston County had sovereign immunity in both

state and Federal courts. This impacted investors' risk assessment and many banks and

lending institutions shied away from buying the company's bonds. By the fall of 1878, the

GC&SF lacked the

cash to finish the Brazos bridge which was the only remaining obstacle preventing service to

Richmond. To finish the bridge, the GC&SF advertised for proposals for a short-term loan of $250,000. They

only received one bid, from a private

syndicate led by GC&SF Treasurer George Sealy! The syndicate included several

other officers and members of the GC&SF Board of Directors, plus various

Galveston businessmen and companies. The loan would be for 90 days, and a key term of the syndicate's offer was that

the loan be secured by a Deed of Trust on the railroad's assets, overseen by an

independent Trustee.

GC&SF stockholders needed to approve taking the loan, but that issue was settled when the Galveston County Commissioners

approved. They had little choice since the railroad would otherwise go

bankrupt. The Commissioners subsequently agreed to sell the County's stock directly to Sealy's syndicate

for $10,000, literally pennies on the dollar compared to the $500,000 they paid for it. This eliminated the

legal uncertainties that had hampered the railroad's financial stability, but it

also ensured that company control remained in the hands of Galveston

businessmen whose interests were generally aligned with the County's. A

competitive stock sale -- or worse, a bankruptcy sale of the entire railroad --

could result in some other railroad acquiring control and then managing the

GC&SF (or dismantling it to eliminate competition) to the detriment of

Galveston's interests.

Despite the loan, the

GC&SF made little progress on the Brazos bridge; presumably much of the

funding went to pay outstanding construction bills. When the loan came due

after 90 days, the GC&SF was unable to make the required payment and went

into default. The Trustee forced a courthouse auction on April 15, 1879 which

was won for $200,000 by Sealy's syndicate. Since the syndicate owned two-thirds

of the outstanding shares of the GC&SF and most of its members were also private stockholders, the

syndicate effectively bought the railroad from itself (with the remaining

private stockholders getting nothing.) There was speculation that this had been

the plan all along, i.e. that GC&SF management had allowed the company to drift

into bankruptcy so the Directors could buy it at a greatly reduced price.

Regardless, the new GC&SF corporation was no longer encumbered by the prior

stock issue and was able to sell $540,000 in mortgage bonds. This provided the

cash to finish the Brazos bridge (in October, 1879) and fund additional construction to the

northwest.

In their initial route survey, the GC&SF had expected to serve downtown Richmond, likely sharing the

GH&SA depot for the convenience of connecting passengers. Coming out of

downtown, they planned a route that went west along the south side of the GH&SA

right-of-way (ROW). Three miles out of Richmond, the GC&SF would cross over the

GH&SA tracks and curve to the northwest toward Brenham.

This crossing, called San Antonio Junction for planning purposes, would also

host interchange tracks between the railroads. The major problem that remained

to be solved was actually getting a surveyed ROW into downtown. Richmond was on the

west bank of the Brazos and sat mostly south of the GH&SA ROW. The GC&SF's

Brazos River bridge was sixteen river-miles southeast of Richmond, hence they

were

approaching from the southeast; getting into downtown would

require a ROW through the heart of Richmond. The

GC&SF reportedly asked the city to provide the ROW, but city officials

declined. Perhaps it was due to the numerous residences and businesses that

would need to be bought out or condemned, an expensive and time-consuming

process. Or perhaps they were sufficiently satisfied with the rail service

they'd known for more than two decades that they didn't sense an urgency for the

GC&SF to serve downtown. Whatever the case, without a route

into downtown, the GC&SF had little choice but to pass south and west of Richmond,

approaching the GH&SA ROW nearly a mile west of the GH&SA depot, just

over two miles east of San Antonio Junction. [At this location, the railroads

might have considered adding a "depot track" to downtown, or perhaps a

connecting track to the GH&SA, either of which would have facilitated GC&SF

passenger trains going east to the depot and then backing out to return to the

GC&SF main line. No evidence has surfaced to indicate such an idea was ever

considered, which undoubtedly had its own set of issues.] The end result was

that the depot the GC&SF built to serve Richmond was a mile distant by city

streets from the GH&SA depot.

Foreseeing the difficulty for passengers to change trains at Richmond,

the railroads decided to establish scheduled connections at San Antonio

Junction where they had already agreed to have interchange tracks. Sharing a depot

there for connecting passengers allowed the railroads to help promote (and profit

from) the expected flow of passengers between Texas' two

largest cities, Galveston and San Antonio. Passengers originating or terminating

their trips at Richmond would simply use the depots in town. Before service began, the GC&SF renamed the crossing "Rosenberg Junction", in honor of former

GC&SF President Henry Rosenberg, a member of George Sealy's syndicate. It seems

unlikely that an isolated rail junction sitting out on the prairie three miles

from downtown Richmond would be named for a key member of

the GC&SF management team before service had even started unless the GC&SF

intended to develop a town around it. People began to settle in the vicinity of the

crossing, and by 1881, a Post Office had opened. The town's layout and

construction commenced in earnest in 1883 when the GC&SF bought 200 acres of

land adjacent to the crossing, much of it to the north between the tracks and

the river. At some point, "Junction" was dropped and the community simply became

Rosenberg.

|

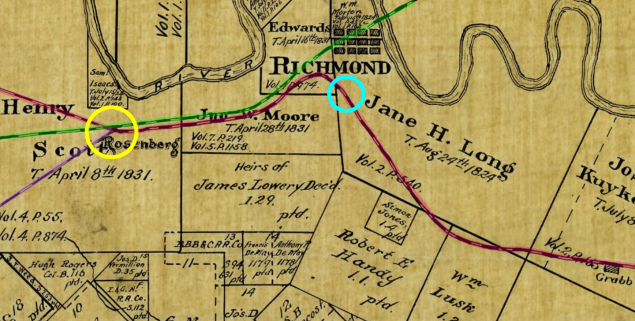

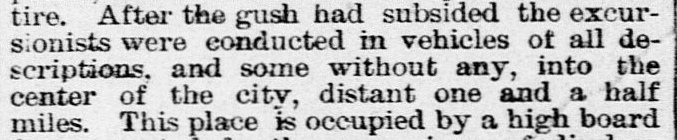

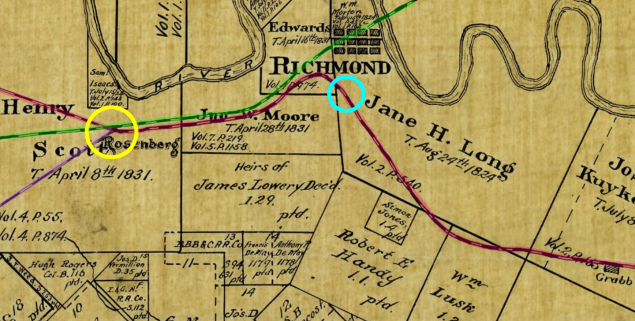

Left:

This 1892 Texas General Land Office map (hat tip, Ken Stavinoha) has been

annotated to show the GC&SF ROW (red highlight) crossing the GH&SA (green

highlight) at Rosenberg (yellow

circle.) By 1882,

Rosenberg had a true Union Depot serving the GC&SF, the GH&SA and the New York, Texas

& Mexican (NYT&M) Railway (purple highlight), which had completed a line from

Rosenberg to Victoria in 1882. The GC&SF depot for Richmond (blue circle) was

more than a mile from downtown, as mentioned (below) in this short excerpt taken from a

lengthy article published by the Galveston Daily

News

of October 19, 1879. The article was written by a correspondent on a special excursion train (of 600 people!) to Richmond that the GC&SF

operated from Galveston to promote its upcoming passenger service (which

commenced two months later.) The train had discharged its passengers at the

GC&SF station in Richmond, likely not much more than a simple platform as it had

only been a few days since the building materials arrived.

|

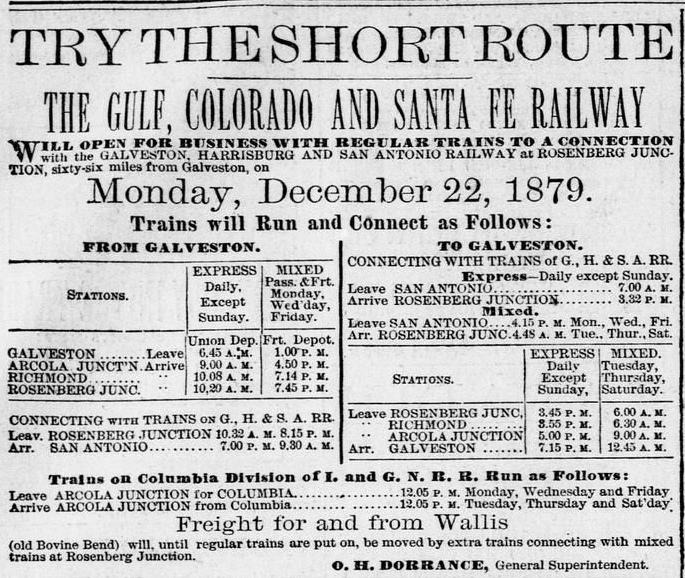

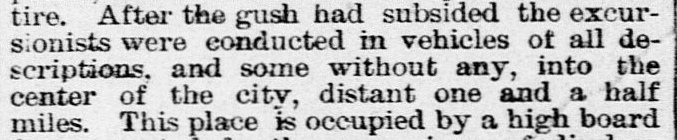

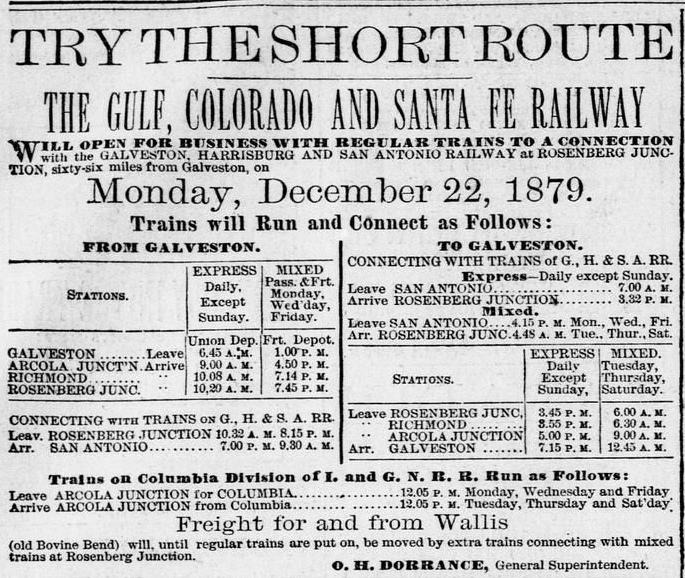

Right:

The

Galveston Daily News of December

21, 1879 carried this advertisement announcing GC&SF scheduled passenger service

to Richmond and Rosenberg Junction commencing the next day. Note the connections

for San Antonio via GH&SA trains at Rosenberg Junction, and the connections for

Columbia (not to be confused with Columbus) via I&GN trains at Arcola Junction.

Right:

The

Galveston Daily News of December

21, 1879 carried this advertisement announcing GC&SF scheduled passenger service

to Richmond and Rosenberg Junction commencing the next day. Note the connections

for San Antonio via GH&SA trains at Rosenberg Junction, and the connections for

Columbia (not to be confused with Columbus) via I&GN trains at Arcola Junction.

The ad mentions "Freight for and from

Wallis" to move by extra trains at Rosenberg. Wallis was the next town,

about sixteen miles northwest, in the narrow corridor between the Brazos and San

Bernard Rivers that had been identified by GC&SF route planners early on. It was named for GC&SF Director J. E. Wallis, who was also a member of Sealy's syndicate. As the ad makes clear, by the date of initial service to Rosenberg, tracks were already in service to Wallis for work trains. There was

an existing community there ("Bovine

Bend") with sufficient commerce potential that the GC&SF decided to show it as a viable service

point, even if not by regular trains.

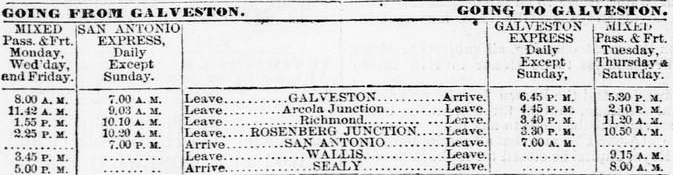

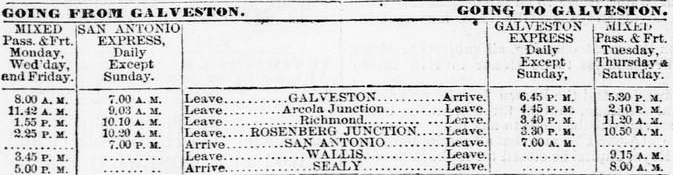

Below: Passenger service to Wallis and

Sealy, the next town farther north, commenced

January 16, 1880, less than a month after initial service to Richmond and

Rosenberg. This schedule in the

Galveston Daily News of January 15th

shows the GC&SF had begun using "Galveston Express" and "San

Antonio Express" to name its connecting service with the GH&SA.

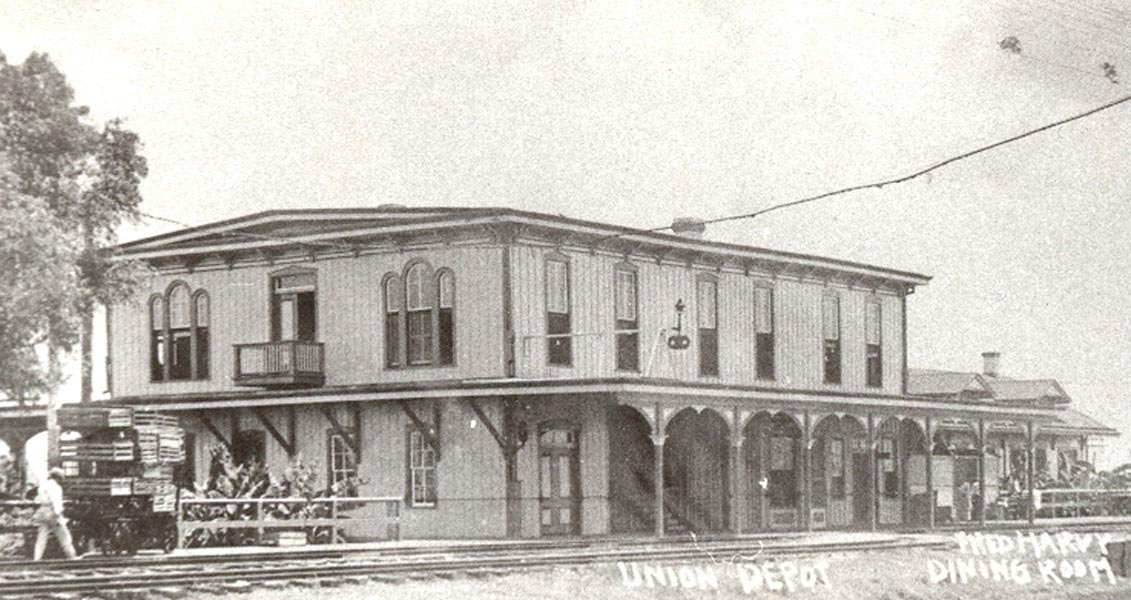

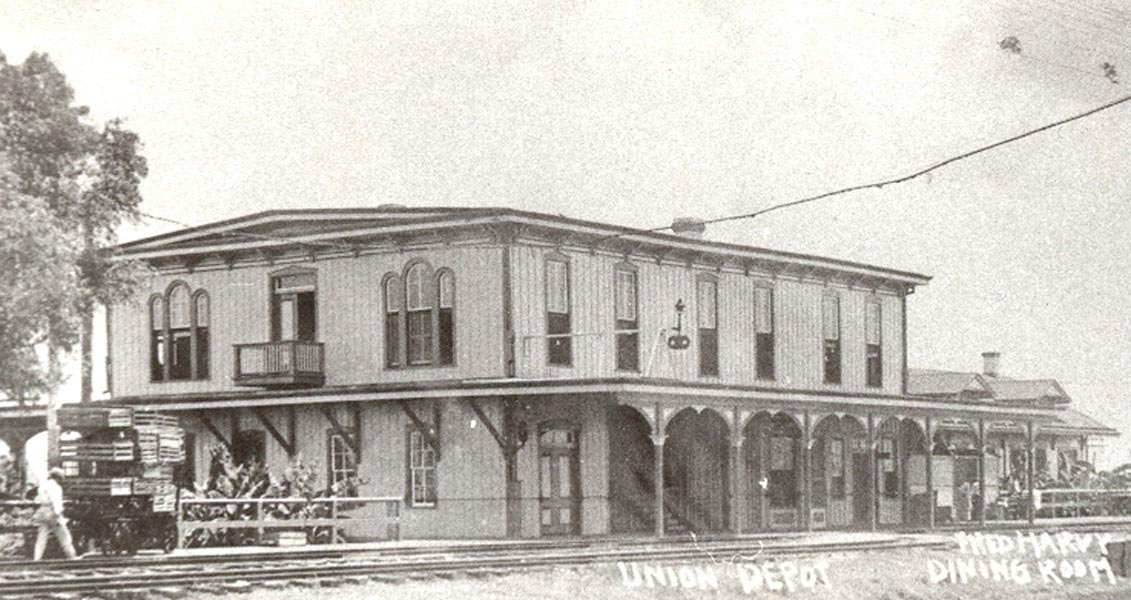

Above: This undated photo of Rosenberg

Union Station (Ken Stavinoa collection) faces northeast showing the southwest

corner of the depot. The tracks in the foreground and the train order signal

belong to the GC&SF, with Tower 17 roughly a quarter mile to the left (west).

The GH&SA tracks are on the other (north) side of the station. The Harvey House

restaurant that opened in 1899 is visible to the right of the station. The

street adjacent to the Harvey House on its far side (east) was 5th St., at least

in those days -- due to street renumbering several decades later, it is now 3rd

St. On the east side of that street, a new joint depot opened in 1917 and Union

Station was closed. The Harvey House appears to have continued operating until

closing c.1923.

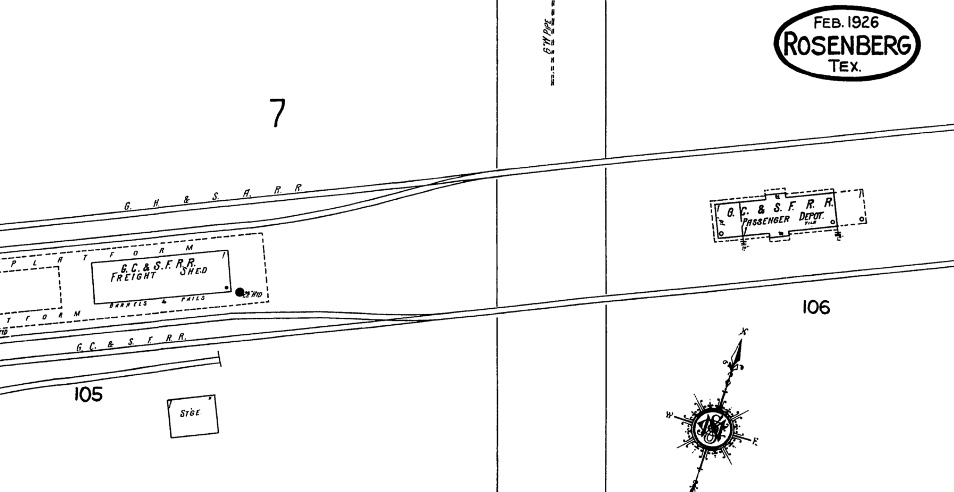

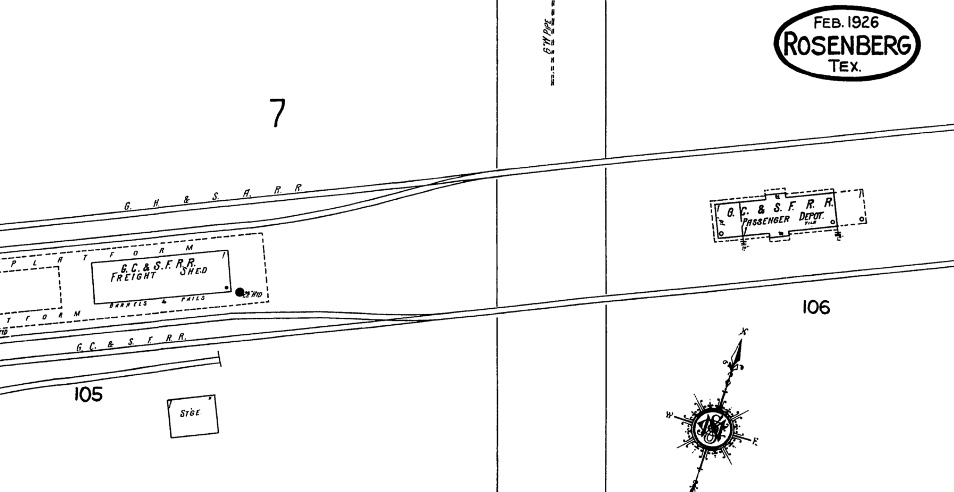

Below: This image from the 1926 Sanborn Fire

Insurance Co. map of Rosenberg shows the 1917 passenger depot sitting east of

5th St. (present day 3rd St.) between the GH&SA and GC&SF tracks. Although the cartographer

identifies it as the GC&SF depot, it served both railroads.

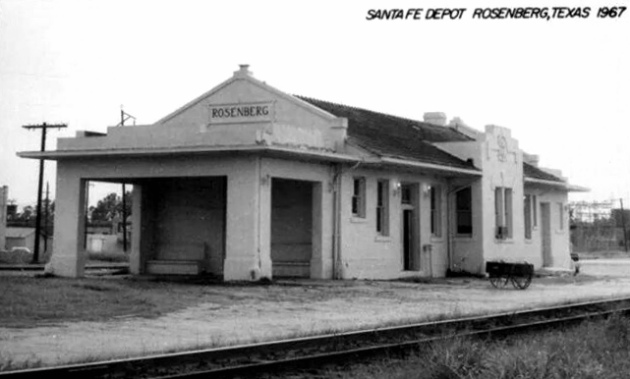

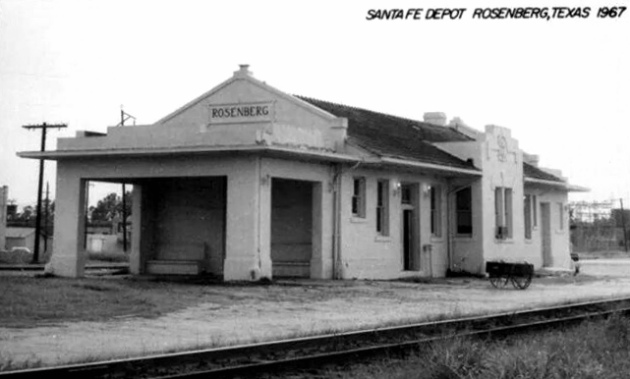

Above Left: The new joint

passenger station for Rosenberg opened in 1917 and survived

until 1980. (H. D. Connor Collection, 1967)

Above Right: The 1917 joint passenger station sits

amidst the palm trees (a tropical style park built by the GC&SF) in this undated photo of Rosenberg. Note

what appears to be a semaphore

signal rising above the trees. The white building in the foreground is the

Express Agency for shipping packages by train.

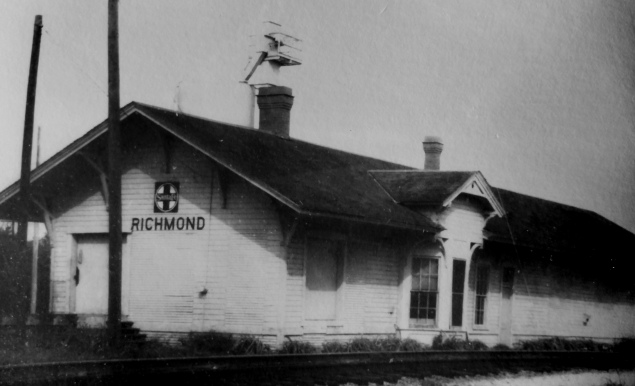

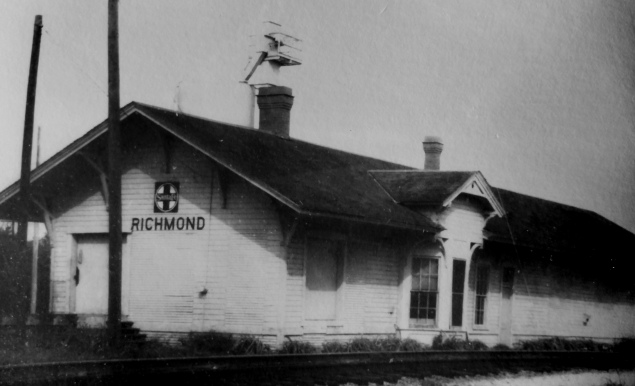

Above Left: The GC&SF eventually built a

standard depot at Richmond, apparently at or very close to the location that had

hosted the original 1879 structure.

Sometime between 1958 and 1970, this depot was removed. (Ken Stavinoha

collection) Above Right: The

depot foundation remains visible in this 1970 aerial image. The road that

crosses the tracks to the left of the foundation is Austin St., a grade

crossing that remains intact on the west edge of Richmond. ((c) historicaerials.com)

The third railroad at Rosenberg was the New York, Texas

& Mexican (NYT&M) Railway, chartered in 1881 as part of a grand

plan to build a railroad from New York City to Mexico City. The enterprise was

organized by Italian financier Count Joseph Telferner. Work

began in Texas with construction of a 91-mile line from Rosenberg through

Wharton to Victoria.

It was completed in 1882, mostly built by laborers brought in from Italy (and

thus nicknamed "the Macaroni Line".) The NYT&M's plan was curtailed when

the railroad was acquired by SP in 1885, although it continued to operate under

its own name. In 1900, an NYT&M branch

line was built south from Wharton to Van Vleck to serve the rich agricultural

area of the lower Colorado River valley. In 1905, SP fully merged the NYT&M into

the GH&SA. Because the Macaroni Line branched off the Sunset Route a short

distance west of Rosenberg, the NYT&M was not officially associated with the

Tower 17 interlocker when it was authorized for operation by the Railroad Commission of Texas

(RCT) on July 23, 1903. The interlocker was a 27-function electric plant

manufactured by

the Taylor Signal Company.

The diamond at Tower 17 continues to see heavy traffic. The GH&SA

Sunset Route is now owned

by Union Pacific (UP) while the GC&SF line is part of Burlington Northern

Santa Fe (BNSF). During the UP/SP merger in the 1990s, Kansas City

Southern (KCS) obtained rights to operate on UP tracks between Beaumont and

Robstown, a vast distance that enabled KCS to

connect its Port Arthur - Kansas City main line with the Texas Mexican Railway

(of which KCS had controlling ownership) at Robstown. KCS' authorized route

through Rosenberg required its southbound trains coming out of Houston to continue west to Flatonia on UP's Sunset Route.

There, KCS trains turned south to Victoria and continued to Robstown

via Placedo. The Macaroni Line presented a route 61 miles shorter between Rosenberg and Victoria, but the

tracks had been out of service since 1986

(with 85 miles from Victoria to McHattie, near Rosenberg, formally abandoned in

1993-95.) In 2000, KCS was given the right to reestablish service over the

Macaroni Line if desired. After a 2004 study of the feasibility of

rehabilitating the route, construction commenced in 2007. Operations over the rebuilt line began in 2009 and continue today.

Tower 17 was the last traditional

manned interlocking tower in Texas. Tower 16 in Sherman and

Tower

47 in El Paso both closed in 2001 leaving Tower 17 as the last holdout until

it closed on February 10, 2004. Albeit somewhat non-traditional, the last

operational interlocking tower in Texas controls the lift bridge over Galveston Bay

(although it appears that this control system may no longer be referenced as

Tower 97.) Thanks to the Rosenberg Railroad Museum,

Tower 17 did not suffer the demise of so many such towers in Texas. It was

relocated to their museum site, just a few blocks from its historic home.

Above Left: James Starkey from Templeton, MA visited Tower 17

on November 30, 2000 and took this photograph of BNSF 722

in Warbonnet

paint rolling past the tower. Above Right: interior photo of Tower 17 (James Starkey photo)

Below: Tower 17 now sits at the Rosenberg Railroad Museum (Jim King photo,

November 2012)

|

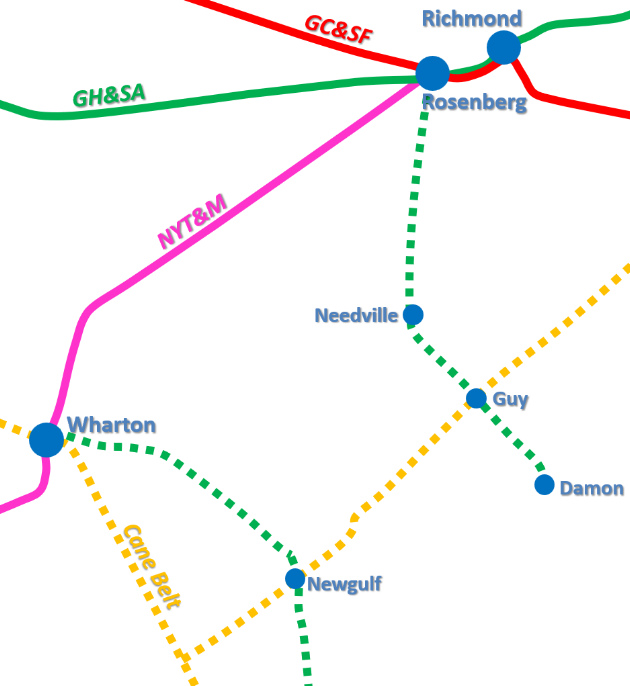

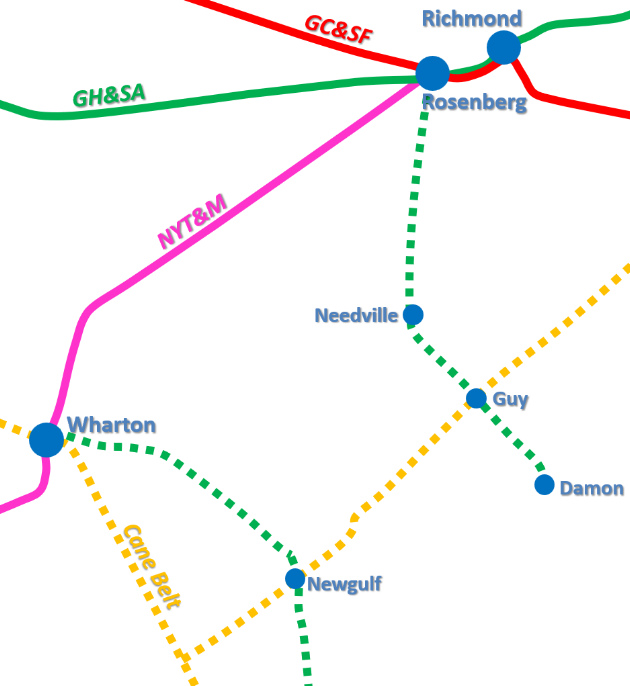

Above: In addition to the main lines built by the GH&SA, the GC&SF and the NYT&M, the GH&SA also built south from Rosenberg in 1918 to

serve mineral extraction at Damon Mound. Left:

The line to Damon came off the ex-NYT&M line, went eleven miles south to Needville,

then southeast five miles to cross the Cane Belt Railroad (a GC&SF property) at Guy, then six additional

miles to Damon. After SP abandoned the short Guy - Damon segment in 1944, the branch became known as the Guy Subdivision

and it survived another 42 years as an alternate

route to Victoria. This was feasible because SP's ex-NYT&M branch from Wharton to

Van Vleck passed through Newgulf, a town which had Cane Belt tracks from Guy.

Hence it was

feasible for SP trains coming east from Victoria on the ex-NYT&M to turn south at Wharton,

proceed to Newgulf, turn east on the Cane Belt to Guy, and turn back north on the Guy

Subdivision to Rosenberg. In both directions, this alternate route was valuable to SP whenever tracks between Rosenberg and Wharton were congested or blocked (e.g. a

derailment, or, as in 1950, when a bridge burned.) This alternate route was specifically identified in a

1936 agreement between SP and the Order of Railway Conductors which stated

"Movement over the Wharton Branch, Damon Branch, and over the Santa Fe will be

made only as the exigencies of the service require."

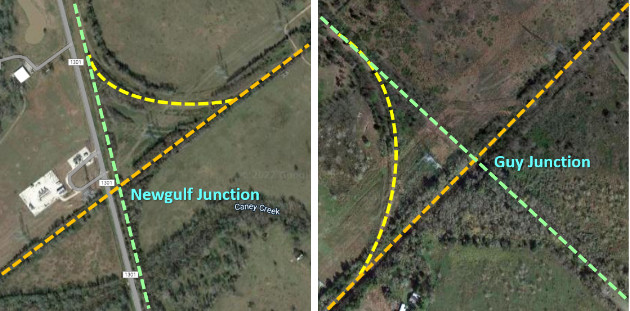

Below: The tracks

are

gone, but the junctions at Newgulf and Guy can be discerned from the tree

lines. Neither was interlocked.

|

Historic Tower 17 to close in January

2004!

Bill Waldrop, Houston, 11/9/2003

I went to UP Tower 17 (Rosenberg)

today, and what we have long feared has happened. UP signal crews

are now installing a new interlocker control building that will

replace Tower 17, the last remaining operating tower in Texas.

The small metal control building is in, a microwave link is set-up,

and they are working quickly running wires, etc. According to a UP official I spoke with

about this, he stated the tentative date for the changeover is

the first week of January, 2004. The signal guys are going to have to

replace all switches (and possibly the signals as well) that are

controlled by the manned tower because they are not compatible

with the current computer control system. The tower will come under the direct

control of UP's Glidden Sub Dispatcher based in Spring. We are

not sure how the BNSF will have any control of their line crossing

UP at this tower, but I know their dispatcher sits very close

to the UP dispatcher in the Spring Dispatch Center, so I'm sure

it will be easily coordinated. The good news out of all this is the

fact that the tower will NOT be torn down! In fact, UP will be

moving it a few blocks east to the Rosenberg Railroad Museum,

where they have already measured for the concrete base, etc. I've heard different accounts about how

old this tower is and how long it has been in service...anywhere

from the late 1800's to the early 1900's. It still uses the original

equipment to control the switches and signals (manually pulled

levers by the operator on duty). We all knew this was coming for many

years, but reality has hit in the fact that it will happen very

soon. I hope everyone has their pictures of this last operating

tower in Texas, it's surely a classic, and it will be sorely missed.

It's the end of an era.

Above: Looking west from

Rosenberg down UP's Sunset Route toward Eagle Lake, the Tower 17 crossing is

just above the center of the image with white equipment cabinets and vehicles

sitting on the former tower site to the left of the diamond. The BNSF main line from Galveston enters the image at lower left and crosses the

UP tracks at the diamond, disappearing into the northwest horizon at upper right toward Wallis. Just beyond the diamond, a

lengthy siding begins along the Sunset

Route to the right of the main line. The KCS line to Victoria then splits off to the left, disappearing

into the southwestern horizon at upper left. (Abel Garcia photo, 2020)

Special thanks to Ken Stavinoha for his assistance

with material and research for the Tower 17 page!

Sledge

was stuck with the BBB&C so he tried to make something of it. A newspaper

article in the

Sledge

was stuck with the BBB&C so he tried to make something of it. A newspaper

article in the  GC&SF

construction from Virginia Point

GC&SF

construction from Virginia Point

Right

Right