Texas Railroad History - Tower 80 - Houston (Percival,

Belt Junction)

Crossing of the Houston Belt & Terminal

Railway and the

International & Great Northern Railroad

Photos from the John W Barriger III

National Railroad Library

Above: John W. Barriger III

took this photo from the rear platform of his business car in the early 1940s,

apparently having just spotted Tower 80 in the distance (magnified at

right.) His train had come

northbound onto the main line of the International & Great Northern (I-GN) Railroad

from the adjacent connecting track (note switch positioned

against the main track.) The signal post numerals show that Barriger was at

Milepost 145.9, one-tenth of a mile north of Tower 80's listed timetable location

of 146.0. (See purple arrow in the diagram below.)

Below Left: Moments

earlier, Barriger's train had passed over the East Belt tracks of the Houston,

Belt & Terminal (HB&T) Railway. At that diamond (in the foreground), Barriger

had a closer view of Tower 80 a hundred yards to his left sitting in the

northeast quadrant of the East Belt's crossing of the I-GN. Visible in the far

distance is HB&T's North Belt which Barriger's train exited using Belt

Junction's east

connector. The switch visible beyond the diamond controlled whether northbound trains

merged eastbound onto the East Belt or continued north to cross the East Belt

and merge onto the I-GN, as Barriger's train was doing when he snapped this

photo. (See green arrow in the diagram below.)

Below Right: A few seconds beforehand, Barriger took

this photo just as his train cleared the switch off the North Belt onto the east connector.

The North Belt was the "Passenger Main", the primary route for I-GN and other

passenger trains departing Union Station to the north. The opposite route at the

switch was the west connector that curved westbound onto the

main line of the Burlington - Rock Island Railroad to Dallas. Barriger's

destination was Palestine, as evidenced by additional photos in this

sequence from the John W. Barriger III National Railroad Library. (See blue

arrow in the diagram below.)

Above: Barriger was shooting south from the rear

platform as his train was moving north, from the bottom of the image to the top

along the dotted red line. His first photo (blue arrow) was taken where his

train left the North Belt (pink arrows) onto the east connector. He took the second photo (green arrow) shortly after his train

had taken the connecting track that crossed over the East Belt (orange arrows).

The switch visible in that photo is the continuation of the east connector ("A") that curved onto the East Belt near the tower. The last

photo (purple arrow) occurred immediately after coming onto the I-GN main line

(yellow arrows.) The car in that image ("B") is on Hardy Rd. immediately west of

the I-GN tracks. There was also a lead ("C") off the

East Belt into the Koppers creosote yard; the yard connected to the I-GN farther

north. This intersection of HB&T's East Belt and North Belt tracks was known as

Belt Junction. (1944 aerial image provided by the Texas General Land

Office and Google Earth)

The Houston & Great Northern (H&GN) Railroad

commenced construction in 1871

with a plan to build from Houston to the Canadian border. By the end of

1873, the east

Texas town of Palestine was the northern extent of

the tracks, about 150 miles from Houston. The International Railroad also had

tracks in Palestine as part of its plan for a main line between Fulton, Arkansas and Mexico.

The International had begun construction at Hearne, roughly the mid-point of its

route, and by 1873 had built northeast to Longview via Palestine.

With their goals and their tracks connecting in Palestine, the H&GN and the International joined

forces to create the International & Great Northern (I-GN) Railroad. The I-GN expanded to become

one of the major railroads in Texas, but not without enduring several

bankruptcies.

Fifty years later, the I-GN was coming out of a lengthy receivership in excellent shape physically and financially.

By then (1922), it served numerous major Texas cities and towns, among them Houston,

Galveston,

Fort Worth, Longview, Waco,

Bryan/College Station, Austin,

San Antonio and Laredo, a vast swath of Texas

commerce. Its new owners tried to sell it to the St. Louis San Francisco

Railroad ("Frisco"), but the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) withheld

approval. This potential sale alarmed the Missouri Pacific (MP) Railroad; it

wanted the I-GN as its entry into the Texas market. To prevent the I-GN from

falling into unfriendly hands, MP orchestrated the I-GN's acquisition by

the New Orleans, Texas & Mexico (NOT&M) Railway. The NOT&M was a collection of

railroads known more commonly as the "Gulf Coast Lines" (GCL), originally part

of Frisco but independent after Frisco's receivership in 1913. With I-GN safely

added to the GCL portfolio, MP bought the GCL in 1925 with ICC's approval,

gaining the I-GN and the rest of the GCL railroads. Among these were two, the

Beaumont, Sour Lake & Western (BSL&W) and the St. Louis, Brownsville & Mexico

(SLB&M), that each owned 25% of the Houston Belt & Terminal (HB&T) Railway.

Thus, acquiring the GCL in 1925 instantly gave MP half ownership of the HB&T,

and full ownership of three railroads in Houston: I-GN, BSL&W and SLB&M.

The HB&T had been chartered by four railroads twenty years earlier, the other

two being the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe Railway ("Santa Fe") and the Trinity &

Brazos Valley (T&BV) Railway. HB&T's chartered purpose was to construct

a Union Station for passengers and build additional

tracks and yards to facilitate freight interchange around Houston. This was a

rather bold plan considering that, at this time (1905), three

of the four railroads did not have tracks in Houston! Those three were controlled by B. F.

Yoakum, a native Texan who was CEO of the Frisco, and earlier that year had become Chairman of the

Executive Committee of the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad ("Rock

Island"). In those days, several years before its 1913 bankruptcy, Frisco owned the GCL.

The GCL had two railroads, the BSL&W

and the SLB&M, that were preparing to build into Houston. For logistical purposes (and

perhaps community credibility), HB&T needed an owner that was already

serving the city. Adding Santa Fe to the ownership group satisfied this need.

With Yoakum controlling a 75% stake, HB&T's real

purpose was to put track and facility infrastructure into Houston to become

the central hub of Yoakum's Texas railroad network.

What was in it for

Santa Fe? Yoakum had been an executive at Santa Fe a decade earlier, so he knew

them well. Santa Fe only had a branch line into Houston from Alvin, so it made

sense for them to join with Yoakum to compete in the Houston market against

Southern Pacific (SP), which already controlled four railroads in downtown

Houston. SP had a fifth railroad in downtown

Houston, but a lawsuit filed by the Railroad Commission of Texas (RCT)

successfully forced SP to divest the San Antonio & Aransas Pass (SA&AP) Railway

in 1904 (as explained for Tower 2.) SP Chairman E.

H. Harriman had

substantial enmity toward Yoakum, accusing him of using his personal

relationships with RCT commissioners to raise a legal issue more than a decade

after SP had acquired the SA&AP (and he was especially galled because Yoakum

had been the SA&AP's court-appointed Receiver at the time.) Yoakum's executive

career had started with SA&AP under the tutelage of its president Uriah Lott in

the mid 1880s. Lott regarded Yoakum so highly that he chose "Yoakum" as the name

of the south Texas town where SA&AP's shops were to be built. Yoakum returned

the favor in 1903 by naming Lott president of the SLB&M.

When the SLB&M's

northward construction from the Rio Grande Valley

finally reached the community of Algoa in 1906, it

connected with the Santa Fe. Yoakum was able to negotiate rights to use their

tracks to Virginia Point where he had arranged to

use the I-GN tracks into Galveston, which were actually

owned by the Galveston, Houston & Henderson (GH&H) Railroad and leased to I-GN. He tried to negotiate rights to reach Houston via

Santa Fe's branch line at Alvin which was less than five miles west of Algoa,

but Santa Fe did not agree initially. Yoakum wanted to avoid

the expense of building his own line into the city and he didn't

want to duplicate Santa Fe's route; he needed their help in other areas (e.g.

operating

the HB&T and access to Galveston from Houston.) Although the SLB&M rail line

was complete between Brownsville and

Algoa by March, 1906 (as evidenced by contemporary newspaper reports), there

were significant problems with the bridges and ballast across the Brazos River

drainage between Bay City and Algoa. The issues were so severe that it took more

than a year to make the grade worthy of regular service. Occasional special

trains made the trip between Bay City and Algoa, but regular service from

Brownsville all the way to Houston via Algoa and Alvin did not commence until December 31, 1907.

Yoakum's

final agreement with Santa Fe for use of the branch line at Alvin is dated April 1, 1908

and remains in place today for the successor railroads.

The fourth HB&T

owner, the T&BV, also did not serve Houston; it wasn't even

building in that direction! But it became Yoakum's solution to a basic problem

he faced -- he did not have a railroad that operated between north and south Texas. The Frisco and Rock Island both

served Dallas/Ft. Worth, but they had no connection to his GCL railroads in

south Texas. Instead, Yoakum's companies delivered freight to other railroads,

primarily SP, when transfers

between Dallas/Ft. Worth and Houston were required. Yoakum wanted to keep this lengthy freight haul (~ 250 miles) within his

empire, so his solution was to buy a small, central Texas railroad, the T&BV,

and revise its charter for construction of a Houston - Dallas main line. Yoakum arranged for the Colorado & Southern (C&S)

Railway (where he was on the Board of Directors) to buy the T&BV and then sell

half of it to Rock Island. When this occurred on August 1, 1905, the

T&BV had just 79 miles of track, from Cleburne to

Mexia (where it passed within a mile of Yoakum's

birthplace, the tiny settlement of Tehuacana.)

Planning far ahead in his

typical bold fashion, Yoakum negotiated trackage rights for the T&BV between

Houston and Galveston, but there are conflicting answers as to which railroad

provided the tracks. The dean of Texas rail historians, S. G. Reed, states that

it was the Galveston, Harrisburg & San Antonio (GH&SA) Railway that initially provided

rights. RCT's 1913 Annual Report states that T&BV had rights on 46 miles of

Santa Fe tracks between Houston and Galveston. The mostly likely answer is

"both", i.e. GH&SA provided the initial rights, and T&BV switched to Santa Fe

rights

later. Since the GH&SA was legally independent in 1905, but functionally

controlled by SP, it would not be a surprise to find that SP management leaned

on the GH&SA to dissolve the T&BV agreement at some later time, and thus,

T&BV struck a deal with Santa Fe. Whatever the case, Yoakum chartered the

Galveston Terminal Railway (GTR) on August 29, 1905

and assigned its ownership to the T&BV, positioning him to influence freight

hauls through the port of Galveston. Two days later, the HB&T was chartered in

Houston with T&BV as a 25% owner. He then negotiated rights for the T&BV to use

Santa Fe's line between Ft. Worth and Cleburne. Yoakum

finished his busy 1905 by signing a contract with the C&S wherein he agreed

to oversee

revisions to the T&BV's charter and manage construction of the new main line.

|

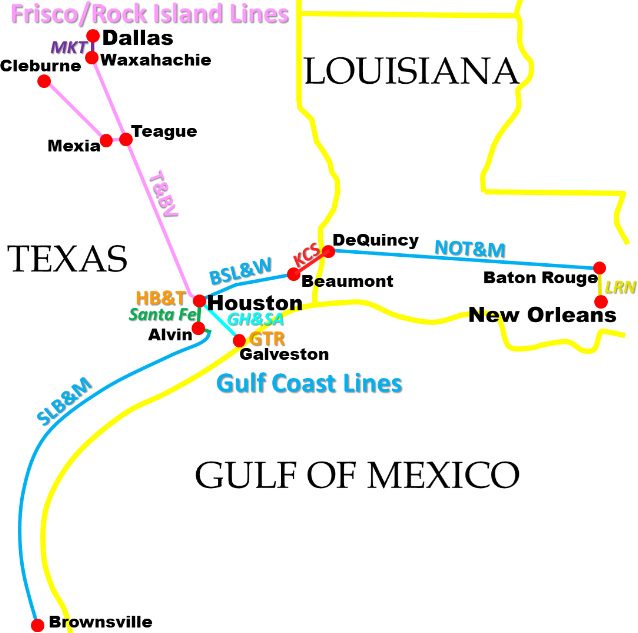

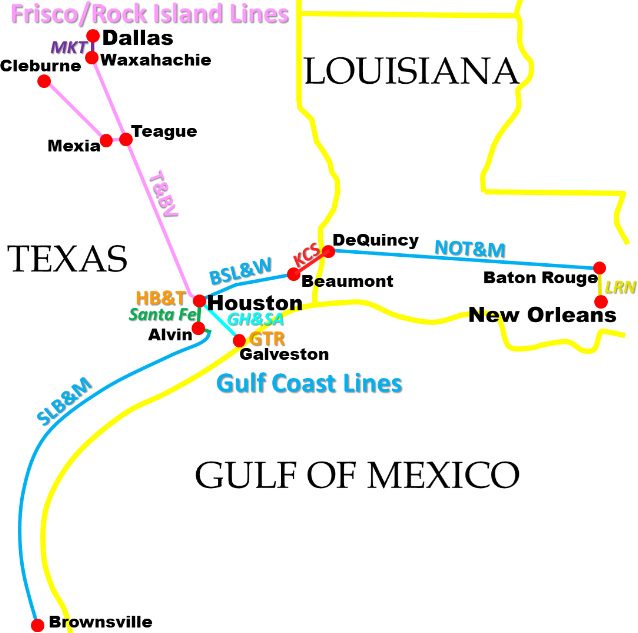

Left: Houston was to be the "Grand Central

Station" of Yoakum's rail empire in Texas and Louisiana. After becoming

Chairman of the Frisco in 1897, Yoakum began planning a major expansion

using Frisco backing of a financial syndicate managed by the St. Louis

Trust Company. The syndicate would build or buy railroads collectively

into the Gulf Coast Lines (GCL). After the Rock Island came under Yoakum

control in 1905, it was used to support his acquisition of the T&BV to

serve as his connecting railroad between his Frisco and Rock Island

lines in north Texas and his GCL lines in south Texas.

The

syndicate chartered the SLB&M in 1903. Construction between Houston and

Brownsville commenced in 1904 starting at

Robstown. Service to Houston using Santa Fe rights from Algoa (near

Alvin) began in 1906. The BSL&W, owning only a 20-mile line from

Beaumont to

Grayburg, was acquired by the GCL in 1905. The GCL directed the

BSL&W to continue west from Grayburg to Houston, an extension

completed in 1908. Construction of the NOT&M commenced in 1905. Service

began in 1909 between DeQuincy and Anchorage (across the river from

Baton Rouge.) To avoid bridging the Mississippi River, Yoakum used a

ferry to reach Baton Rouge and trackage rights on the Louisiana Railway

& Navigation (LRN) Co. from there to New Orleans. Rights from

Beaumont to DeQuincy (via Mauriceville) on KCS

, and more critically, the use of KCS'

bridge over the Neches River in Beaumont,

gave the GCL a continuous line from Brownsville to New Orleans. Those

KCS rights remain in use today.

The T&BV was acquired in August,

1905. Construction to Teague was initiated in 1906, and from there, north

and south to Dallas and Houston, respectively. The main line was

completed in 1907. At Houston, HB&T construction began in 1906 or 1907,

with the North Belt finished in time for T&BV trains to use it. East

Belt construction met the BSL&W in 1908, and then continued around the

east side of Houston between 1910 and 1912. Besides the aforementioned

rights on other railroads, gaps were also filled by the Missouri-Kansas-Texas

[MKT] (Waxahachie to Dallas), the GH&SA (Houston to Galveston, where the Port of Galveston

was served by Yoakum's GTR), and the Santa Fe (Algoa to Alvin to

Houston, and, at least by 1913, Houston to Galveston). The T&BV also had Santa Fe trackage rights from Cleburne to

Ft. Worth (not depicted.)

Other Texas railroads in the GCL

portfolio prior to its acquisition by MP in 1925 included the

Orange & Northwestern, and the San Benito

and Rio Grande Valley. The Sugar Land Railway

near Houston was acquired by MP and assigned to the GCL in 1926. |

The newly chartered HB&T began planning to

build tracks in Houston. A line around the east side would serve the rapidly growing

industrial port along Buffalo Bayou east of downtown. This "East Belt", however,

was not nearly as important to Yoakum as construction of a line north from

downtown. The

T&BV and BSL&W would soon be arriving in Houston from the northwest (1907) and

northeast (1908), respectively, and Yoakum's priority was to build a

shared track, the "North Belt", so their trains could access the new

passenger station downtown and

continue farther south to HB&T's new yard. Santa Fe already had a spur (dating to 1896) that went north from

downtown to an interchange with the Houston East & West Texas (HE&WT) Railway

a mile north of Buffalo Bayou.

Starting there, HB&T built a half mile farther north and crossed the HE&WT, a

location that became interlocked as Tower 71. The North Belt

continued

two miles farther north where it ended, to await the arrival of the T&BV.

It is likely that HB&T curved the North Belt tracks to

the west and built an additional distance to meet the approaching T&BV.

Yoakum began T&BV construction in 1906, first

building 14 miles from Mexia east to the community of Brewer, which Yoakum

incorporated as Teague, his mother's maiden name. Teague

would become the T&BV's major yard between Dallas and Houston, and it

remains an important yard today. From

Teague, Yoakum built south, getting within 77 miles of Belt

Junction by the end of 1906. In 1907, Yoakum finished the main line

construction. He built north from Teague, stopping in Waxahachie

where

he was able to obtain rights to use the MKT tracks to cover the remaining distance

to Dallas. To the south, the T&BV entered Houston from the northwest and turned due east toward

Belt Junction where it met the HB&T to access the city. Service between

Dallas/Ft. Worth and Houston/Galveston began immediately over the new main line

which, due to its lower grades and fewer curves, was faster and less expensive

to operate than SP's competing route via Hearne. SP

retaliated by building a new line that literally paralleled T&BV's tracks for 42

miles (!), but that's another story...

The

BSL&W had also been bought by Yoakum in 1905 and had been assigned to the GCL. A year

earlier, the BSL&W had completed its only rail line, 20 miles from

Beaumont to

Grayburg, a settlement one mile south of the town of Sour Lake. The line's purpose

was to use Beaumont as the processing and shipping point for oil coming out of

the booming Sour Lake oil field, but Yoakum had other ideas for the BSL&W's

tracks; they already

covered a quarter of the distance from Beaumont to Houston, and he needed a

route east from Houston. At Beaumont, the

GCL negotiated trackage rights on the Kansas City Southern (KCS) to DeQuincy,

Louisiana, and from there, GCL was building its own NOT&M route to New

Orleans (which included a Mississippi River ferry at Baton Rouge and trackage

rights from there to New Orleans.) Completing the BSL&W's remaining

distance into Houston would eventually give Yoakum continuous service from

the Rio Grande Valley to Houston to New Orleans on the GCL, which was

accomplished by 1909.

To meet the BSL&W in

1908, a switch was added at the north end of the North Belt from which a track

curving to the east was built. This was essentially the northern terminus of what would

become the East Belt. Given HB&T's long range plans, it's likely that an

east/west "straight through" track was also built at this time. The resulting

triangle of tracks ultimately became known as Belt Junction. The track to the

east crossed both the I-GN, where Tower 80 would be installed, and the HE&WT, where

Tower 76 was commissioned in

late 1908. For the I-GN crossing, Tower 80 first appeared in RCT's tower list in

1910, but with no operational date. Tower 80 was finally approved on July 25,

1913 by RCT with a 14-function mechanical

interlocker. Since only 14 functions were required, it is likely that the Tower 80

interlocker controlled the HB&T/I-GN diamond and little else (the minimum

interlocker configuration for a simple crossing was generally twelve functions: four home signals,

four distant signals, and four derails.)

RCT's October 31, 1913 list of approved

interlockers identified Tower 80's location as "Houston", with no additional

detail. A 1915 report changed the location to "Percival". Later reports also

cite the location as "Houston, Percival" and "Percival (Houston)." This

reference is associated with I-GN's Percival Yard (originally "Percival Avenue

Yard", the street no longer exists) located immediately

south of Tower 80. Although Belt Junction and Tower 80 were synonymous in later

years, it did not begin that way; RCT's published lists never used Belt Junction as a reference

for Tower 80's location. The connotation of Belt Junction was the intersection

of the East Belt and North Belt which initially was very close to, but entirely west of,

Tower 80.

|

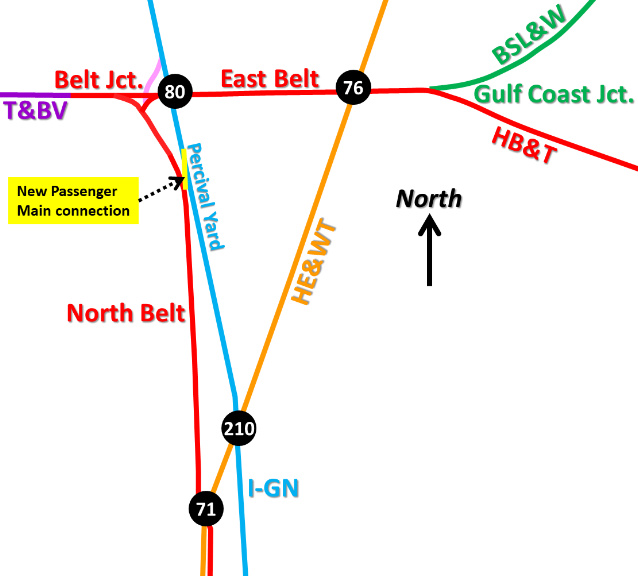

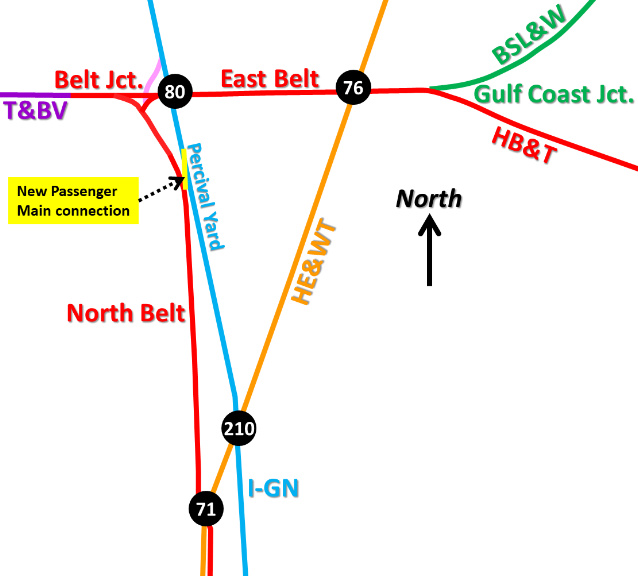

Left:

At the north end of the North Belt, it's likely that the HB&T curved

west to connect with the approaching T&BV in late 1907. To meet the

arriving BSL&W in 1908, the north part of the East Belt was built across

both the I-GN (Tower 80) and the HE&WT (Tower 76). The Passenger Main

connecting track (pink) for I-GN trains that crossed at Belt Jct. (the

route Barriger took) was likely built when the US Railroad

Administration moved I-GN's passenger services to Union Station during

World War I. It was an expedient solution to get I-GN passenger trains

to/from Union Station, but had the negative impact of a second diamond a

hundred yards west of Tower 80. It wasn't used for freight; HB&T had a

better I-GN freight connection south of downtown which included a

connection with the GH&H.

In 1926, RCT's published list shows that Tower 80's functions suddenly

increased to 23. In 1925, MP had taken ownership of I-GN and become

half-owner of HB&T, so this likely reflected expanded interlocker

controls desired by MP. By 1951, I-GN's Passenger Main connection (pink)

was gone, replaced by a new connection (yellow) at Percival Yard. It is likely that

new connectors were added in the northeast and southeast quadrants at

Tower 80 at the same time. This would allow HB&T switchers and intercity

I-GN freight trains to reach MP's new Settegast

Yard which had opened by the end of 1951. The North Belt then became

exclusively the Passenger Main to Union Station (industries would still

be served by HB&T switchers.) Aerial imagery from

1944 shows very little activity at Percival Yard despite a large number

of tracks. It was likely abandoned soon thereafter in favor

of Settegast Yard, ensuring that the new Passenger Main connection would not

have interference from freight yard operations.

When East Belt construction

resumed southeast from the BSL&W connection c.1910, the result was Gulf Coast Jct.,

named for the GCL trains that used the BSL&W tracks.

The East Belt curved south and ultimately southwest forming a

semi-circular route around the eastern part of the city.

Towers 86 and

87 along this path were commissioned in April, 1911, followed by

Tower

85 in May, 1911. The south end of the East Belt terminated at HB&T's New

South Yard (Tower 117) south of downtown.

At MP's request, Tower

80 took over remote control of Tower 76's

interlocker in 1930. |

|

|

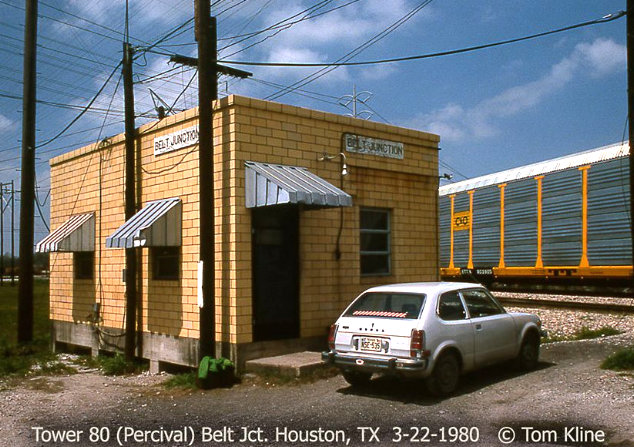

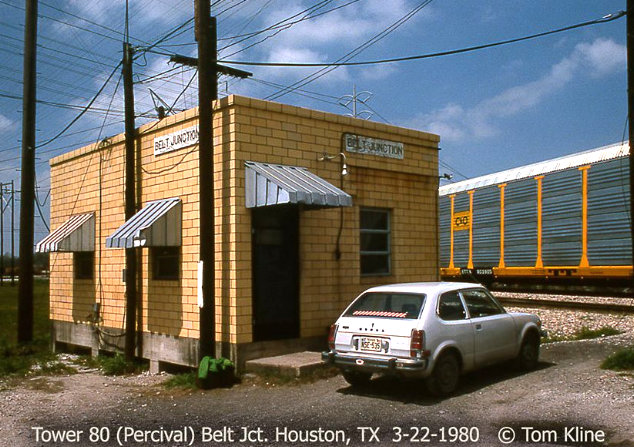

| Above:

Looking east at Tower 80 from Hardy Rd. in January, 1949 (courtesy, Greg Johnson) |

Above:

the newer Tower 80 building, March 1980 (courtesy, Tom Kline) |

|

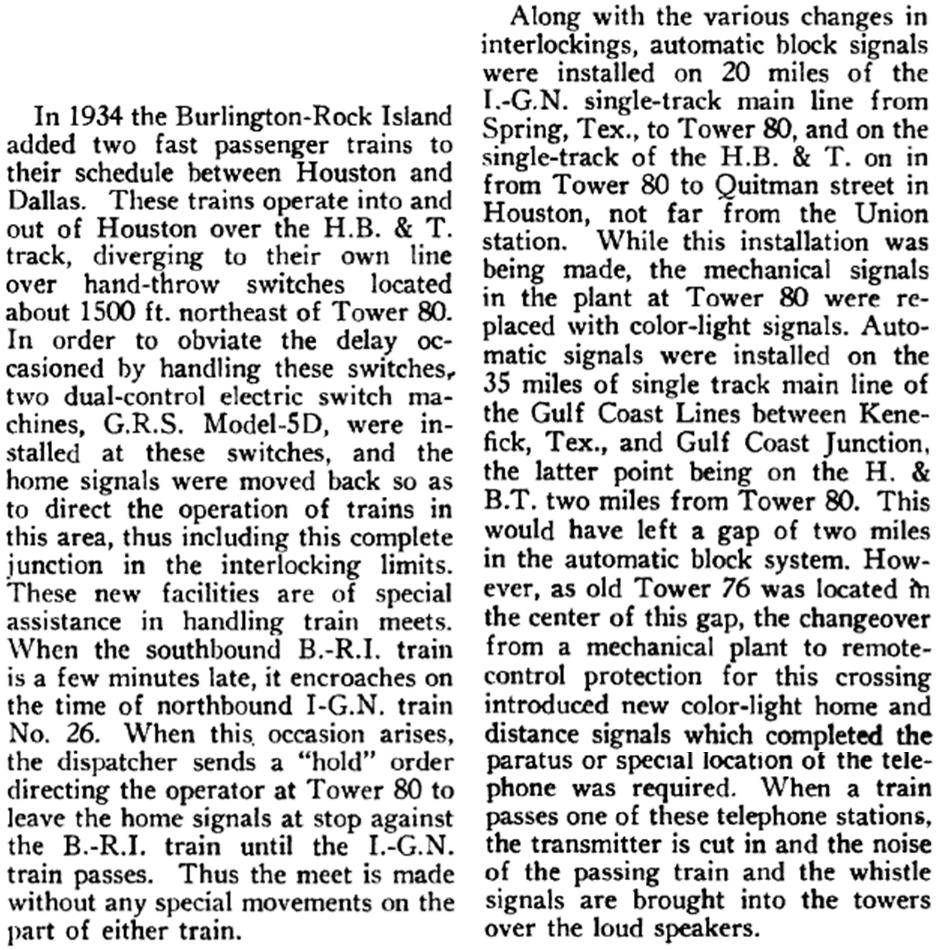

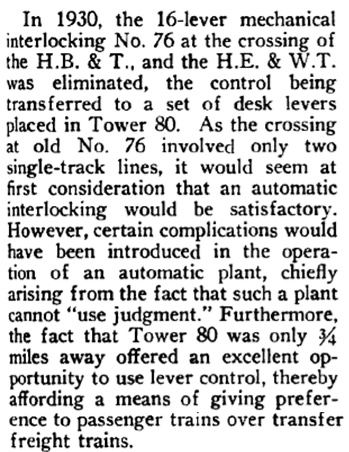

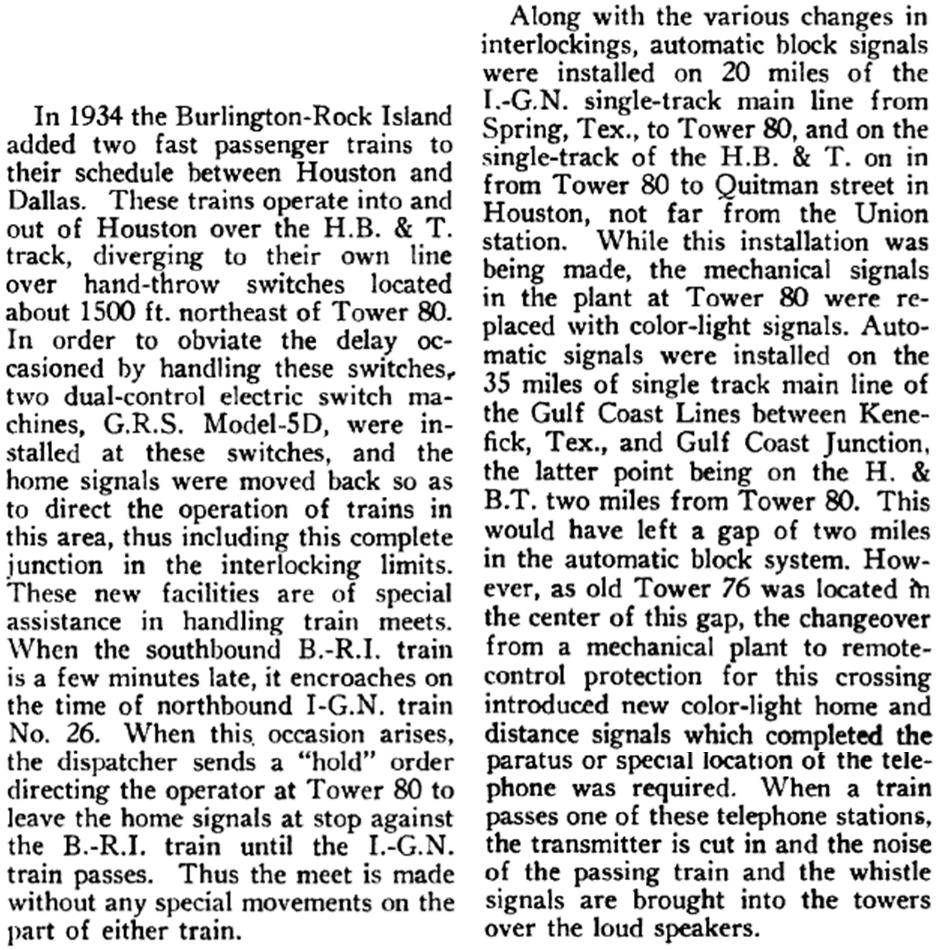

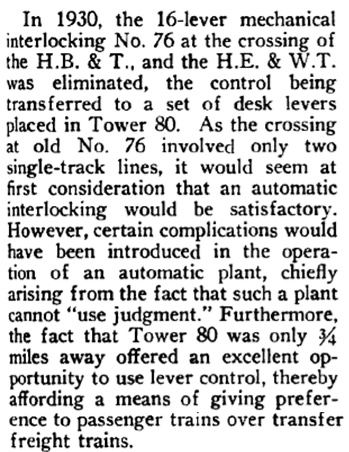

Left and Below: These excerpts are from an article in the

1935 edition of Railway Signaling and

Communications that was written by an MP signals engineer. The

article described the consolidation of interlockers that occurred in

north Houston beginning in 1928, and it explains why the controls for

Tower 76 were incorporated into Tower 80 rather than making Tower 76 an

automatic interlocker.

|

By 1914, Yoakum's takeover of the T&BV had proven to be

financially improvident. Outside of Houston and Dallas, neither the main line

nor the branch from Teague to Cleburne had much population, so there was little

local demand for freight or passenger service. And the few towns of even modest

size all had better rail alternatives: Mexia (SP), Hillsboro (MKT), Cleburne (Santa Fe), and

Corsicana (SP). This left the

T&BV almost entirely dependent on Houston - Dallas/Ft. Worth traffic which was insufficient since

SP, MP and Santa Fe also served the market. The T&BV went into bankruptcy, finally emerging in 1930 as a newly organized company, the Burlington - Rock Island

(B-RI) Railroad. The B-RI's ownership was split equally between Burlington,

which had bought the C&S in 1908, and Rock Island. Various shared operations and

management arrangements for the B-RI were used over the decades to the benefit of

both owners. Ultimately, the main line became part of Burlington Northern Santa

Fe (BNSF), which continues to operate it today (the Teague - Cleburne branch was

abandoned in stages between 1932 and 1976.)

Did the T&BV build

all the way to Belt Junction in 1907, or did it meet HB&T somewhere west of Belt Junction?

If it was west of Belt Jct., there might have been historical

switching rights resulting from the actual meeting point of the T&BV and the

HB&T. Tom Kline reports that a 1973

Rock Island track chart in his collection shows the B-RI ending 3.4 miles west

of Tower 80 at B-RI milepost 60.65, with the remaining distance to Tower 80

marked as "HB&T". Tom explains:

"Operationally

speaking, the tower was where the terminal began and ended for the B-RI. ... As

to a distinct line of demarcation to where the T&BV stopped, it was always

referred to generally as North Shepherd Drive by the B-RI guys. On the days I

did work on the North Houston Switcher out of the North Houston Yard at West

Little York Road, they [B-RI] never worked any customer farther south than Oak

Forrest Drive. There were several spurs between Shepherd and Yale Streets

feeding local shippers and HB&T served them so I guess those were historical

switching rights."

At least in recent times, there do not appear to have

been any spurs between Oak Forrest Dr. and North Shepherd Dr., a distance of ~

1.5 miles. So, if the switching rights related to the original construction, the

T&BV and the HB&T would have met somewhere in this vicinity, with North Shepherd

Dr. being about 3.5 miles west of Belt Junction, consistent with the 3.4 mile

distance on Tom's Rock Island track chart.

|

Left: This

aerial image from 1953 ((c) historicaerials.com) shows two new

tracks added to the junction after 1944: a double track in the NE

quadrant and a single track in the SE quadrant. The original tower is not apparent and

was probably gone. Belt Jct. operations had been moved to a new Tower 80

(red circle) located north of the East Belt tracks, about 125 yards east

of the I-GN/HB&T diamond (green circle). This new building is shown in

Tom Kline's photo above. Personnel reached it on a dirt road (light

blue arrow) that came from a residential street to the south. Tom discusses the new tower building...

"...the location was referred to as 'Tower NX' at one time...a holdover from the telegraph days. NX was the call sign of

the

interlocker. We never called it that but some of the old heads did. The

tower was razed in 1985, and video cameras were put in at

the east switch of the

plant to OS and record car numbers of passing trains."

The

lead into the Koppers creosote yard remained intact in 1953, as it did until the

site was abandoned in the 1980s. Across from it, coming off the east

connector to the East Belt, a remnant of the grade of the original

Passenger Main connector for I-GN (that Barriger used) is visible (yellow). That

connector (and its diamond with the East Belt) had been removed when the

new Passenger Main connector at Percival Yard was installed, at least by

1951 and probably earlier. The Belt Jct. east connector was still intact

even though it had been rendered obsolete by the new SE connector. The

Belt Jct. west connector was still needed for B-RI passenger trains.

In the late 50s or early 60s, a new SW connector was installed

closer to the diamond, and the east and west Belt Jct. connectors were

removed, the last of the original Belt Jct. connecting tracks. This

freed up most of the original Belt Jct. real estate as the junction was

effectively merged into Tower 80. The new SW connector preserved B-RI

access to the Passenger Main and was substantially closer to the new

tower.

|

MP had opened Settegast Yard at least by the end of

1951 to be its primary Houston freight yard. It was located four miles east of

Tower 80, sitting between MP's ex-BSL&W tracks and the East Belt. Intercity MP

trains using the I-GN tracks would take the northeast connector behind the new

Tower 80 building when accessing Settegast Yard. The southeast connector would

facilitate access by HB&T switchers serving industries along the I-GN line. An

HB&T map from 1974 labels the former I-GN line south of Belt Junction through

Tower 210, Tower 26

and the I-GN bridge over Buffalo Bayou as the "Freight Subdivision", distinguished

from the North Belt Subdivision via Towers 71, 26

and 139.

In the late 50s or early 60s, the

original east and west connectors at Belt Jct. were removed. The east connector

had been obsoleted several years earlier by the southeast connector, but the

west connector was still in use for B-RI passenger trains. It was replaced by a

new southwest quadrant connector so B-RI passenger trains could retain Passenger

Main access. The abandonment freed up significant real estate and allowed removal of the

west connector switch from

the Passenger Main near the former Percival Yard. The new southwest connector was also much closer to the

new Tower 80. The Hardy Toll Rd. was built in the mid 1980s along the former

I-GN right-of-way (ROW) south of Spring. Part of the former west connector ROW

was used to allow the road to swing west to avoid passing directly over Belt

Jct./Tower 80.

Tom Kline recalls Tower 80 operations from the early

1980s:

The southeast connector was used by trains off the I-GN Freight Main, usually

stuff coming out of downtown (Congress Yard, off the GH&H from Galveston,

transfers, etc.) or traffic going into downtown, but it never saw the frequency

of movements that the dual connectors did on the northeast quadrant. A few

trains would roll straight north or south on the old I-GN Palestine Sub, but not

many as I remember. The MPís main artery was the east-west line to Settegast,

then diverting onto the Palestine Sub which seemed to get all the traffic.

Tom reports that Tower 80 records show 18 passenger

trains per day in 1952; some undetermined number of these were B-RI trains using

the southwest connector. With the demise of passenger trains when Amtrak was

created in 1971, the southwest connector became virtually abandoned. It now

appears to have been rejuvenated somewhat, most likely as a result of a

restructuring of HB&T's north/south traffic flow. In the early 1990s, HB&T's

former North Belt (Passenger Main) between Tower 71 and Belt Jct. was abandoned,

replaced by a double track routed from Tower 71 to Tower 210 and then back onto

the original I-GN ROW to Tower 80.

The southwest connector off the HB&TĎs B-RI connecting western line was for

passenger trains to get to Union Station. I remember it being in place but

darned near abandoned and never used. There was another leg [the east

connector at Belt Jct.] off this connector going back to the HB&T to form a

wye (which was pulled up after passenger service) and I recall one of the old

B-RI guys telling me they wyed passenger trains there at Tower 80 and backed

into Union Station. Not sure if that was Std. Operating Procedure or occasional.

Iím not sure what the last train was to use the Passenger Main to

Union Station since, just before Amtrak, the only passenger trains running were

the ATSF and SP on (mostly) their own tracks. ... Currently for Amtrakís

operation of the Sunset Ltd., all trains use the Sunset Route to the west of

Houston and depending on traffic levels use either the BSL&W route east or the

old SP Sunset Route to Beaumont. Right now it seems the BSL&W sees the most

trains in both directions but it varies. The BNSF and KCS use the ex-SP line to

Beaumont the most in both directions while UP favors the BSL&W for through

movements, but it all depends on congestion in and between the two terminals.

I-GN continued to operate under its own name and it

subsequently incurred yet another lengthy receivership (as did other components

of MP's system.) When the bankruptcy finally settled, MP was reorganized and the

I-GN was merged into it in 1956. From the early 1980s through the 1990s, there

were substantial ownership, track and roadway changes that affected Belt Jct.

Union Pacific (UP) took over MP, becoming a half-owner of HB&T. The other half

owner is Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF), successor to Santa Fe and

Burlington Northern, each of which owned 25%.

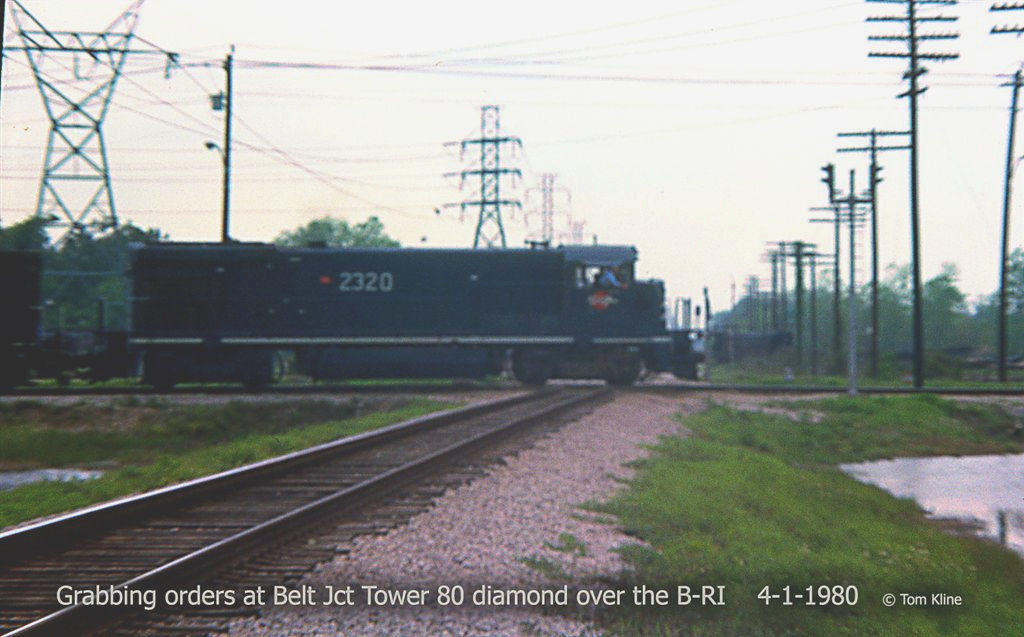

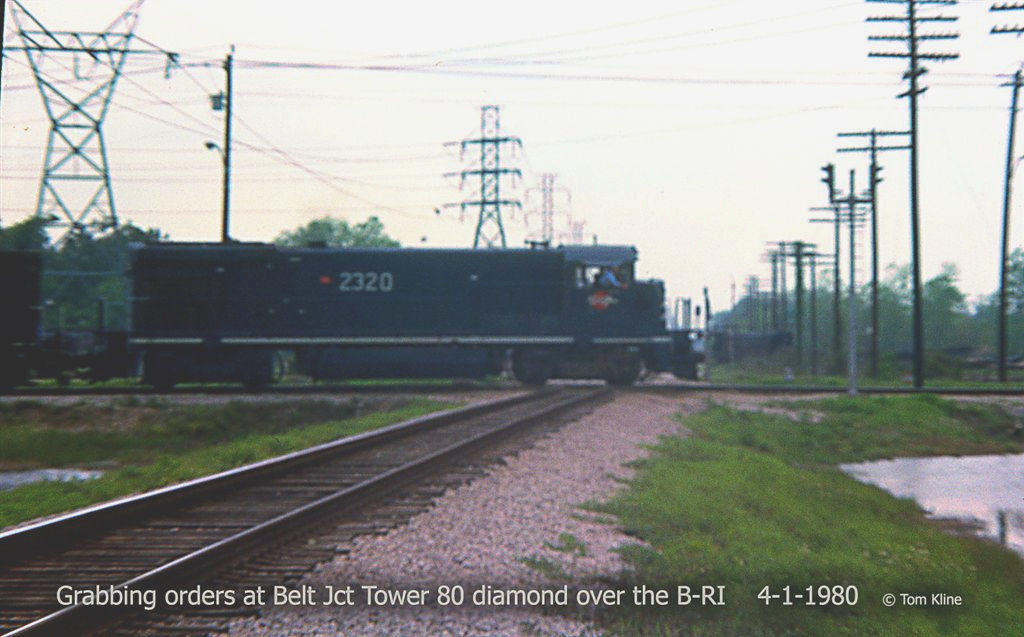

Additional Photos by Tom Kline

|

Tom writes: "A northbound MP freight waits for

a clearance card to be written up at the TO office on one of the

connector tracks in the northeast quadrant of the junction leading to

the Palestine Sub. Notice this connector is double track.

Also notice the homemade order stand under the floodlight on the

engineer's side of the loco. There were three of these in this

area next to the office. They could hold a total of four train

order forks each." |

|

Tom writes: "A horribly blurry shot looking west from the train order office

down the HB&T/B-RI main of a MP freight grabbing orders while headed north off

the "Passenger Main" - now the West Belt - and onto the Palestine Sub. This is

a short telephoto shot and as you can see, the office was a good ways away from

the diamond. I ran down to hang these orders and shot this view out the

west window of the office. Notice the train order signal by the diamond for the

north-south main. In the distance is a bulkhead flat car sitting on the

lead into the Koppers creosote plant which occupied the northwest corner of the

crossing."

|

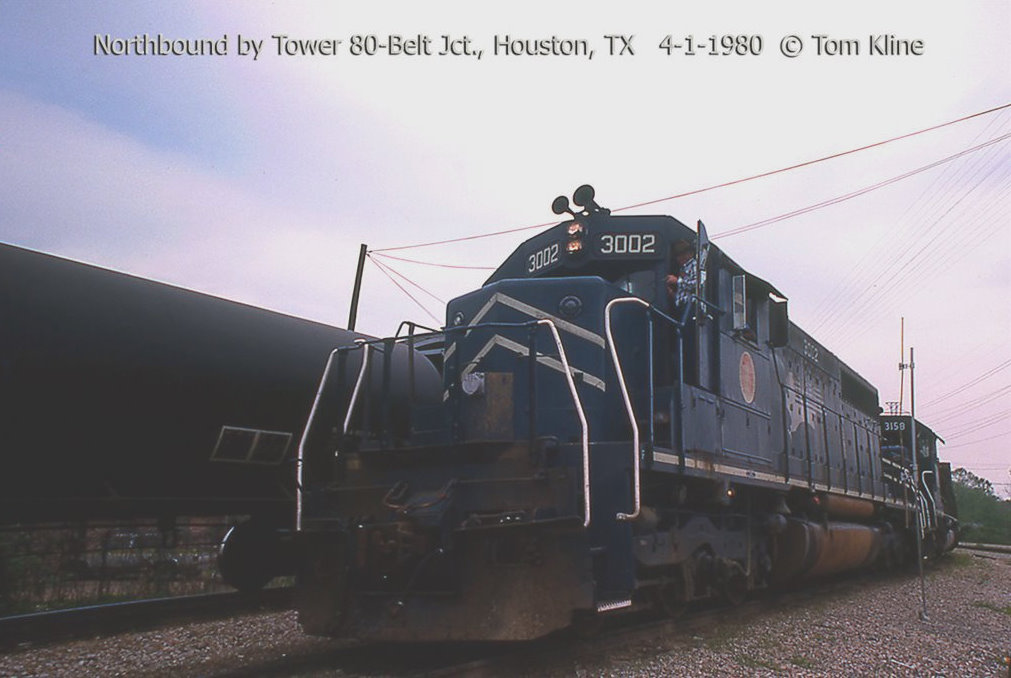

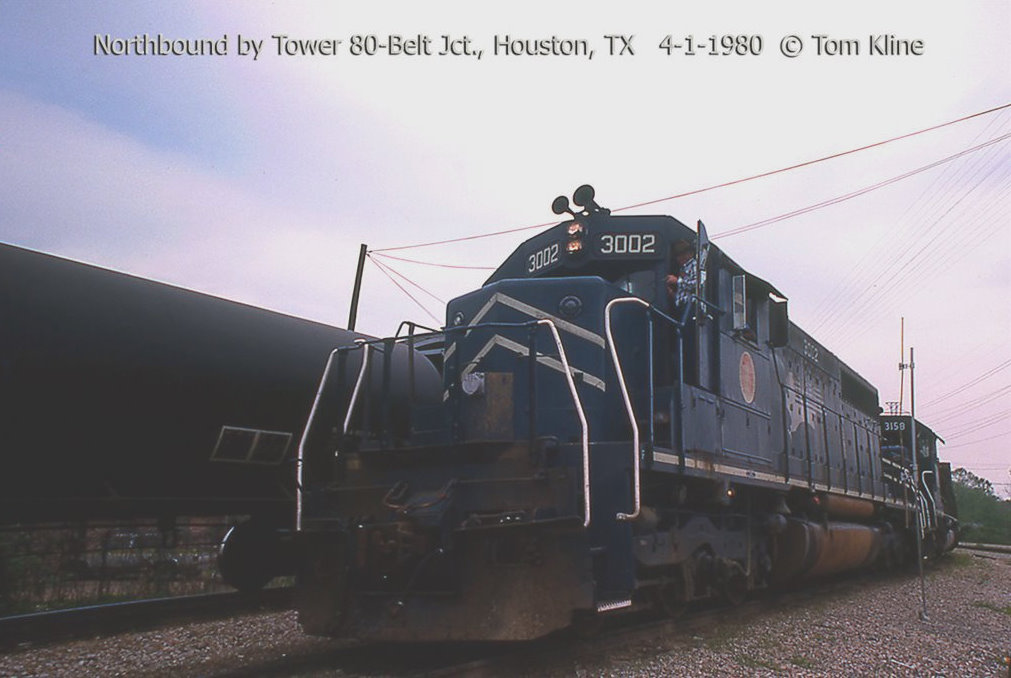

|

Tom writes: "That's me handing up wheel reports

to the conductor of a Teague-bound train on the B-RI passing the Tower

80 office. Notice the connector track in the background, occupying the

southeast quadrant of the plant." |

|

Tom writes: "On the inside of the two connector

tracks to the Palestine Sub a northbound eases past after grabbing

orders. Notice the High-Speeder order post to the right which replaced

the home made stand seen in the night photo above." |

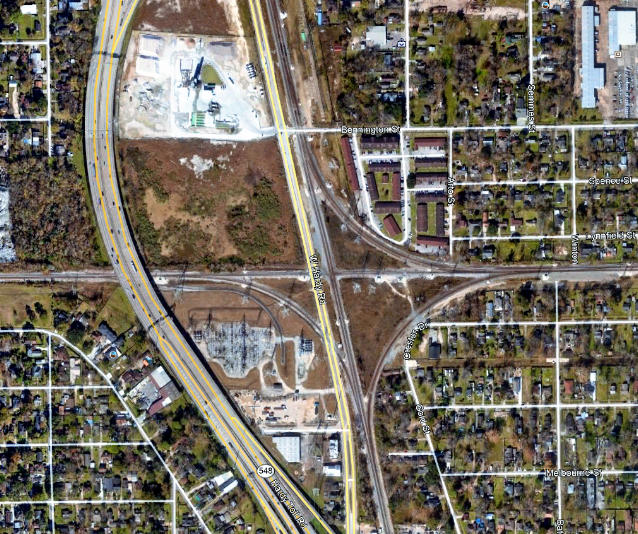

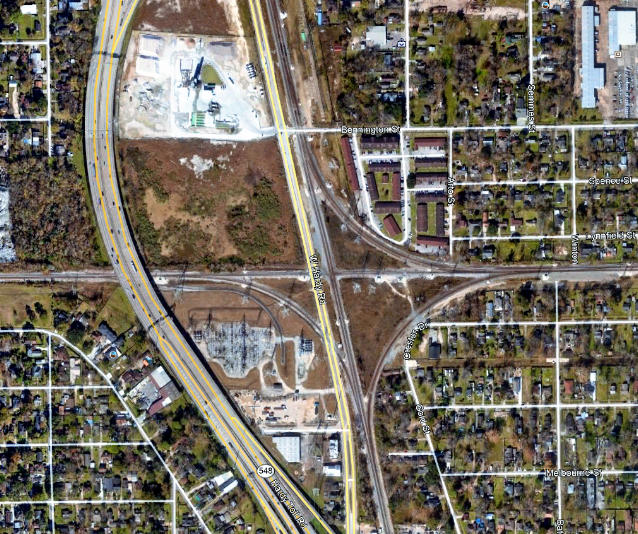

Above Left: 2018 satellite

image of Belt Jct. Above

Right: This 2019 Google Street View looks up the dirt road that

led to the brick building at Belt Jct. The building was across the tracks from

the green cabinet. Below: 2019

elevated Google Street View east toward Belt Jct. from the Hardy Toll Rd.

Two 2019 views from the Hardy Rd. grade crossing at Belt Jct.: west (above)

and east (below) (Google

Street View)