Texas Railroad History - Towers 114 (Sugar Land), 161 (Arcola

Junction) and 162

(Sugar Land Junction)

The Story of the Sugar Land Railway

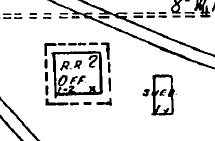

Above Left: This image

taken from a northwest-facing 1937 aerial photo of the Imperial Sugar Company in

Sugar Land shows Tower 114 in the center adjacent to office

buildings within the company's refinery and headquarters complex. The Sugar Land

Railway is visible from the lower left corner crossing the Southern

Pacific (SP) tracks and passing the west side of the tower before curving farther west off the top of the image. Although the buildings near the

tower have all been demolished, the one in the upper right corner (with

four tall windows on the left side wall) survived to at least 2013.

Above Right:

Imperial Sugar Co. provides

this 1932 street scene within their plant complex that happened to capture Tower

114 in the distant background (magnified inset at top.) The camera is facing

east-northeast, parallel to the SP main line

at right which appears to show a locomotive and several box cars.

Below: This March, 2017 Google

Street View shows tracks remain embedded in Kempner Street, which had recently

been closed. These were presumably Sugar Land Railway main line tracks based on

the angle of approach to the former SP main line at right. Tower 114 would have sat in the area of disturbed earth at the left edge

of the image.

Above: This December, 2012 Google Street View shows the

aforementioned building with the four tall windows. The tracks passed between

the smokestacks and the cylindrical tanks, both of which are on the other side

of Oyster Creek. The creek is 70 feet wide where the tracks crossed, and though

not readily apparent in this image, the rail bridge over Oyster Creek

remains in place near the tree in the center.

Below: In this April, 2022 Google Earth satellite image, Kempner

St. has been rerouted to a new intersection with Main St. The original roadway

is closed but the tracks remain visible in the pavement. At left, two Sugar Land

Railway bridges over Oyster Creek remain intact, but most of the buildings and

other structures in the Street View above have been removed. The smokestacks

remain standing as of March, 2025, off the image to the left.

|

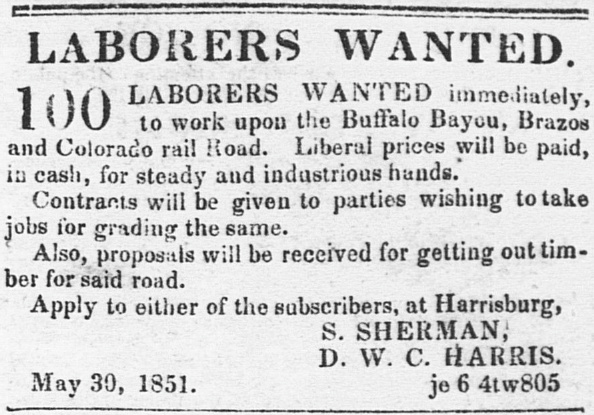

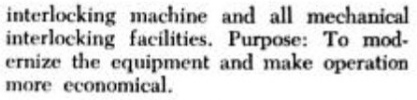

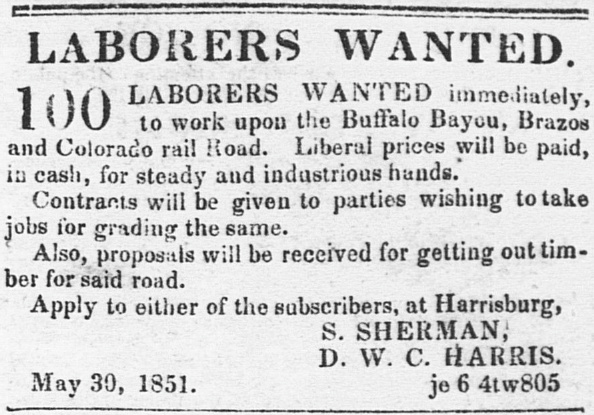

The Buffalo Bayou, Brazos and Colorado (BBB&C) Railway

was the first railroad in Texas. Although Railroad Commission of Texas

(RCT) records claim twenty miles of track was laid in 1853 to Stafford's

Point, the construction actually began in 1851. (RCT didn't exist until

1891, so its "records" were anecdotal, forty years later.) The BBB&C

charter had been granted in February, 1850, and track-laying began in

1851 at

Harrisburg, a river port on Buffalo Bayou southeast

of Houston from which steamboats could reach the Gulf of Mexico.

Left:

Houston Telegraph & Texas Register,

June 20, 1851

Stafford was reached by 1853. An advertisement

by the Superintendent of the BBB&C that was datelined "August

31, 1853, Harrisburg" but published periodically in the

Richmond Texas Sun and other newspapers provided a round-trip

schedule to Stafford.

Writing about land bonuses offered by the

state to railroads under construction, the

Austin State Gazette of November 10, 1855 wrote... "The

Buffalo Bayou, Brazos and Colorado Railroad Company will undoubtedly

complete its road as far as Richmond during the present year." A

huge public celebration for the arrival of the railroad in Richmond was

held in January, 1856. Building into Richmond required bridging the Brazos

River, a formidable obstacle. |

The coastal

prairie through which the BBB&C passed had been an area of sugar production

dating back to the 1820s. In the 1840s, the sugar cane crop had begun to expand

significantly, making sustained commercial sugar milling viable. Despite

excellent soil, sun and rainfall in the "Sugar Bowl" area of Texas, sugar cane

was not easy to grow. It required crop rotation and frequent replanting to

achieve good yields. The supply of locally grown cane was often insufficient for

the capacity of the area's mills, so the owners developed other

sources. Inbound shipments of sugar cane from distant plantations and outbound

shipments of processed sugar became ideal freight

for railroads.

If the BBB&C was planning on substantial sugar business,

it certainly helped that the grade between Stafford and Richmond went through the Oakland

Plantation, a large agricultural operation with sugar cane and other crops. The

plantation had been purchased by Benjamin F. Terry and William J. Kyle in 1853,

a partnership that just happened to have the BBB&C's track construction

contract! In 1858, a Post Office for Sugar Land (often misspelled

Sugarland) five miles west of Stafford (and eight miles east of Richmond) was established for the

plantation community that had settled near a large sugar mill built in 1843.

Jonathan Waters, a BBB&C investor and company officer, owned another nearby

sugar enterprise, the Arcola Plantation, a dozen miles south of Sugar Land. To

get rail service into the vicinity, Waters and other plantation owners farther

south needed a north / south railroad to connect with the BBB&C.

By

1856, merchants in Houston had noticed that much of the trade brought into

Harrisburg by the BBB&C's rails was going south on Buffalo Bayou to

Galveston

rather than north on the bayou to Houston. They proposed the BBB&C's charter be amended

by the Legislature to authorize the city of Houston to issue bonds for a branch

line 6.5 miles south from the city center to "tap" the BBB&C. After the branch was built --

Houstonians called it the Houston Tap -- plantation owners saw that extending

it

farther south into the heart of the Sugar Bowl would bring them the

rail service they desired. To this end, the Houston Tap & Brazoria (HT&B) Railway

was founded to acquire the Houston Tap and extend it to Columbia, a

port on the west bank of the Brazos River, about where the river became reliably

navigable some thirty miles from the Gulf of Mexico. The HT&B acquired the Houston Tap and proceeded to build south across the BBB&C.

This immediately created the first grade crossing of two railroads in Texas at Pierce Junction, named for

Thomas W. Peirce (with the unusual "ei" spelling, but the Post Office

forced the community that grew up around the junction to revert to the standard

spelling.) Peirce was a wealthy Bostonian attorney, railroad investor and

landowner who had sought his fortune in Texas. HT&B construction continued south

and reached the Brazos River in 1860. Columbia's name morphed into

West Columbia when people began using

East Columbia as the name of the community across the river where the

railroad ended. The rail line became

known as the Columbia Tap, a nickname that has persisted to the

present.

The Civil War caused the

physical deterioration and financial ruin of Texas railroads. Among many other

difficulties, the war prevented the HT&B from bridging the Brazos River into West Columbia (and

a bridge was never built.) After the war, the Columbia Tap was sold for $500 at a sheriff's sale due

to its substantial indebtedness to the State of Texas for construction loans. In

1873, the Columbia Tap was acquired by the Houston & Great Northern Railroad

which merged with the International Railroad later that year to form the

International and Great Northern (I&GN) Railroad. [Coming out of

bankruptcy in 1922, the corporate name became International - Great Northern,

"I-GN".] Under I&GN ownership, the Columbia Tap was repaired and service resumed

between Houston and East Columbia.

The BBB&C had a similar experience. After defaulting on its construction

financing, it was acquired in 1870 by an investor group with Thomas Peirce

becoming President. Peirce rehabilitated the BBB&C and renamed it the Galveston,

Harrisburg & San Antonio (GH&SA) Railway. The GH&SA resumed

building west, entering San Antonio in 1877. Due to its

westward trajectory, Peirce coined the nickname Sunset Route which

remains in common use. Within a year, Peirce was developing plans to extend the

GH&SA to El Paso to connect with

Southern

Pacific (SP) which was building east from California with plans to create a

southern transcontinental route. With SP financing, Peirce built simultaneously

eastward from El Paso and westward from San Antonio beginning in 1881. In

January, 1883, Peirce drove a Silver Spike where the two GH&SA construction

crews met near the Pecos River. As SP had reached El Paso by then, the spike

signified completion of the southern transcontinental rail line from California

to New Orleans. SP had obtained a financial interest in the GH&SA by financing

Peirce's

construction, and it eventually acquired the GH&SA outright.

The economic recovery in the immediate aftermath

of the Civil War did not extend to the Oakland Plantation, which

continued to decline. The owners, Kyle and Terry, had both died in the

early 1860s leaving a void at the plantation. Much of its land was sold to E. H. Cunningham of

San Antonio who built a large sugar refinery on the property in 1879. Although the Sugar Land

Post Office closed in 1886, the local economy stimulated by the Cunningham Sugar

Co. improved enough to justify a new post office in 1890. Immediately south of Cunningham's property,

the Arcola Plantation had rebounded from the Civil War. It had been

purchased by Thomas Peirce in 1872, but resold a week later to Thomas W. House.

House was a wealthy merchant, private banker, civic leader, former mayor of

Houston, and an active investor with interests ranging from railroads to natural

gas to cotton. He was also the first vendor of ice cream in Houston, which

might explain his interest in sugar (and perhaps his election as mayor!) House made substantial investments in

his plantation and began to produce excellent sugar. The mill was located at

"House's Sugar House", which became settled as the community of House. The

Columbia Tap ran along the eastern side of the plantation less than two

miles from House. Across the northern part of the property, a new railroad, the

Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe (GC&SF) Railway, was granted

a right-of-way (ROW) in 1877. Its tracks from

Galveston to Richmond crossed the Columbia Tap on plantation property at

what became known as Arcola Junction. The new line was a

consequential development for area commerce as the GC&SF evolved to

become a subsidiary of the Atchison, Topeka

& Santa Fe Railway, a major Midwest railroad, in 1887.

Although Santa Fe and I&GN

tracks were nearby, Cunningham's only rail outlet was with the GH&SA at Sugar Land. Convinced he was not getting

competitive shipping rates, Cunningham sought other options. Working

with Galveston investor G. B. Miller and others, Cunningham developed a

plan to build the Sugar Land Railway (SLRy.) It was

formally chartered

April 14, 1893, but the plan had leaked out well

before then. The Galveston Daily News

of March 23, 1893 quotes Mr. S. K. Wheeler, Santa Fe's superintendent of transportation,

saying "I do not see why Cunningham and Miller will build a road twenty-five

miles long to connect with the International and Great Northern when they can

reach the Santa Fe by building about eight miles. Our road can handle the sugar

from Galveston as cheaply as the Southern Pacific...".

Wheeler

was mistaken; the SLRy planned to connect to the I&GN's Columbia Tap

at Arcola Junction, only a dozen miles from Sugar Land. Wheeler had

assumed that the SLRy planned to build to an I&GN

connection much farther south at Anchor (which would have

required crossing the Santa Fe anyway) but he was on to something. The

Port of Velasco had reopened in 1891 and the Velasco

Terminal Railway (VTR) had completed a line between Anchor and the port in

1892. The idea of importing sugar cane through Velasco

was a long-term possibility that Cunningham was considering.

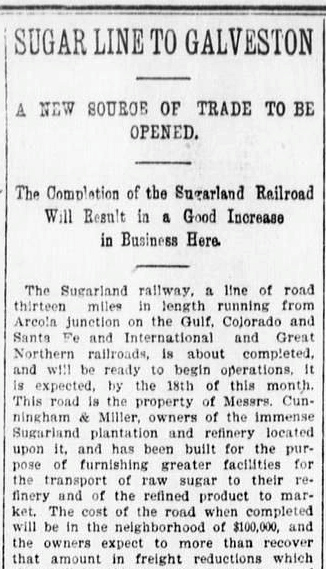

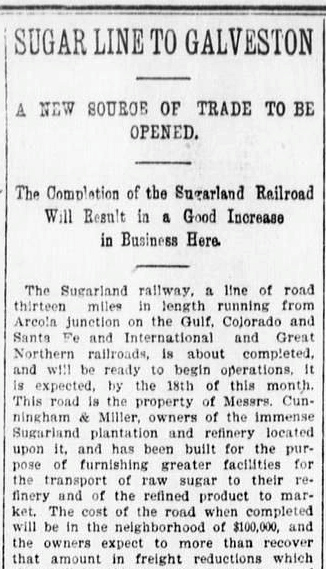

Right: Galveston

Daily News, October 14, 1893 |

|

Cunningham proceeded with his plan to seek alternate

carriers for his raw materials and products. RCT records show that the initial

construction of the SLRy was

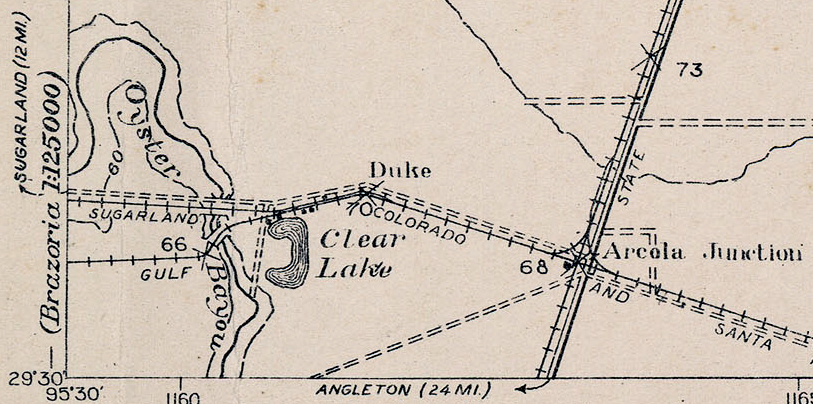

14.2 miles from Sugar Land to Arcola in 1894. Arcola was an ambiguous name; there were at least three communities that

used the name over a two-mile stretch of the Columbia Tap. In this case,

Arcola referred to Arcola

Junction where Santa Fe crossed the I&GN. The route passed through the

community of Duke located along the Santa Fe tracks a mile west of Arcola

Junction. The SLRy made connections with Santa Fe at Duke and with the I&GN at

Arcola Junction.

|

While the SLRy construction was underway, the

Galveston Daily News of August 6, 1893 reported

that "The International railway company is constructing a spur from Arcola

to the House plantation." This "Arcola" was a community on the

Columbia Tap that the railroads called Hawdon

to eliminate confusion with other uses of the Arcola name. Since the

plantation had its own private rail network, it is undetermined whether

this was entirely new construction or perhaps an existing private track

that I&GN was rebuilding to its standards. Whatever the case, the spur's

construction to House was never reported to RCT even though I&GN

officially advertised service to House's.

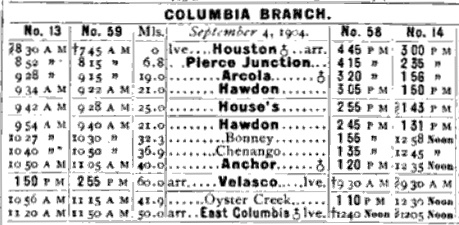

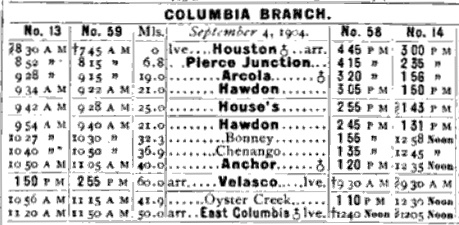

Left:

This timetable in the January, 1905

Official Railway Guide (ORG) shows that at least by

September, 1904, I&GN was advertising service to House ("House's")

over the spur from Hawdon.

The service to House does not appear in the November, 1898

ORG. The 4-mile distance between Hawdon (21.0) and House (25.0) is

inaccurate, apparently a doubling of the actual distance (~ two miles)

to indicate that service to House always required a round trip on the

spur. |

Cunningham was importing a large volume of sugar cane

and low grade sugar products from Cuba for his mills and refinery. Routing

through the Port of Velasco instead of Galveston remained an intriguing option.

Velasco was about the same rail distance from Sugar Land as a Galveston routing

via the Santa Fe at Arcola Jct, but it was closer than the Galveston route used

by SP. Galveston was one of the biggest ports in the U.S., hence dock congestion

sometimes delayed inbound shipments. Cane and other products arriving at Velasco could

be brought immediately to Anchor and transferred to the I&GN for the trip north to Arcola

Junction. There, the cane cars could be picked up by the SLRy and taken to Sugar

Land. It seems likely that Cunningham experimented with this routing, but direct

evidence of any sustained use has not been found. The VTR went into bankruptcy

in 1899, but by 1907, the Houston & Brazos Valley (H&BV) was

operating the Anchor - Velasco line successfully.

|

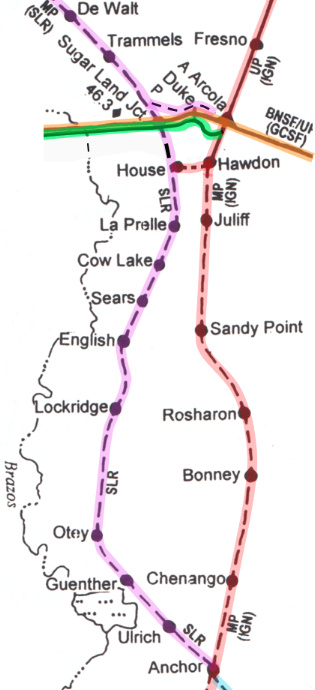

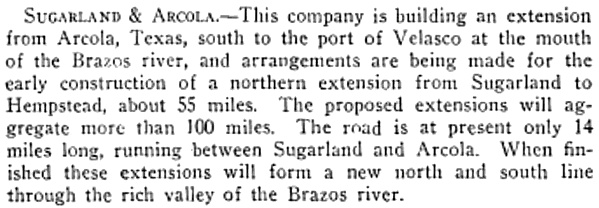

Left: overview

map (not all railroads depicted) showing the eventual extent of the

railroad construction south of Sugar Land

The SLRy advertised a connection with both I&GN and Santa Fe at Arcola Junction.

In his 1941 tome

A History of the Texas Railroads (St. Clair

Publishing, 1941) S. G. Reed

confirms that Cunningham extended the SLRy

"...to Arcola, connecting with

the Santa Fe...". There was a SLRy rail connection with the I&GN

at Arcola Junction -- it is visible on 1930 aerial imagery -- but it is

doubtful that there was a Santa Fe rail connection. More likely, the

"connection" was simply the ability of SLRy passengers to access both railroads. A

physical rail connection to the Santa Fe at Arcola Jct. would have duplicated the capability at Duke

only a mile away.

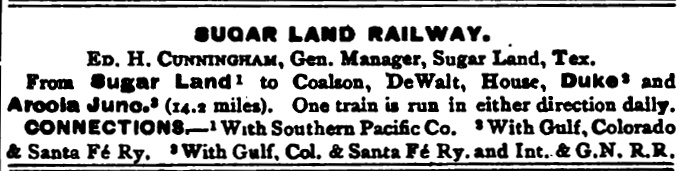

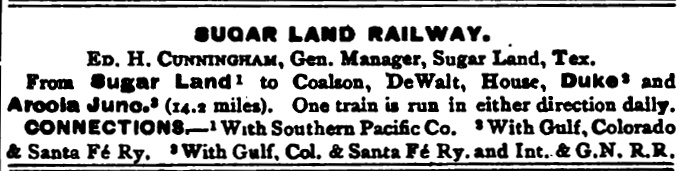

Above: In the

November, 1898 ORG, the SLRy advertised passenger connections with Santa Fe at

both Duke and Arcola Jct., and with the I&GN at Arcola Jct. Service to "House" was listed,

which would seem to imply

that

the SLRy had somehow built across the Santa

Fe to reach House, but that was not what the timetable was indicating. Cunningham

was merely advertising a stop on the SLRy at the closest point to House (which, as

listed above, was

between DeWalt and Duke) for a carriage ride south across the Santa Fe

tracks, either directly to House about three miles away, or to the

Arcola Plantation's private rails, about a half mile away. |

Above: To reach Arcola Junction, the SLRy's 1894

construction went southeast from Sugar Land, turning to a generally east heading

as it neared the Santa Fe tracks at Duke. It then paralleled the Santa Fe line

on the north side until it reached the vicinity of Arcola Jct. There, it curved

north in the northwest quadrant of the junction to connect with the I&GN main

line (or more likely, a siding.) There is conflicting evidence as to whether the

SLRy tracks to Duke were actually present in 1930; the ROW is clearly visible.

There's a question that pertains to the

pink arrow. A 1929 USGS topographic map depicts a Santa Fe - I&GN connecting

track in the northwest quadrant. Originally, the only such connection was in the

northeast quadrant (which is visible on this imagery.) As will be

explained later, 1929 was

after the SLRy's tracks to Arcola Jct. had been abandoned. It seems likely that

this new connection would have been built atop the previous SLRy curve in the

northwest quadrant, in which case it would likely have joined the Santa Fe main

line about where the pink arrow is located. In theory, it should be depicted on

this 1930 imagery. If so, the switch is most likely in the vicinity of the pink

arrow, but the image resolution is inadequate to make a determination. It

would only have permitted eastbound Santa Fe movements onto

the I-GN northbound, and southbound I-GN movements onto the Santa Fe westbound.

On the above composite image, the bright area along the

south side of the Santa Fe tracks immediately west of the I&GN diamond appears

to be where

Santa Fe's depot was located. Santa Fe documentation locates the east end of the

depot very close to the diamond but does not specify which side of

the tracks. It seems likely that Santa Fe and the I&GN would

have shared a depot -- for such a small outpost, it would be hard to justify

two depot buildings. A faint line between the depot area and the apex

of the SLRy's

curve in the northwest quadrant of the junction looks like a footpath, i.e.

suggesting

that the SLRy's passenger stop was on the curve.

There's also an obvious bright path parallel to the I&GN tracks leading south away from

the depot area at the diamond. It makes a right-angle turn to the east to cross over the I&GN and

the highway (now FM521.) It reaches the east side of the highway where there's another bright area; magnification shows a building of some

sort, perhaps a parking area with a restaurant, store or other facility? Suffice

to say that all three railroads had the means to support transiting passengers

at Arcola Jct., and there may have been local businesses interested in serving

these passengers.

The Eldridge Era and the Imperial Sugar Co.

In 1906, William Eldridge and Isaac Kempner formed a partnership to acquire

the Sartartia Plantation a few miles west of Sugar Land. It had been one of the

largest sugar plantations in the area, owned and developed by Captain L. A.

Ellis, but it had gone into receivership after Ellis' death. Eldridge was experienced in sugar production and railroads having assisted in

the construction of the Cane Belt Railroad through

Eagle Lake which had been acquired by Santa Fe in

1903. The partners soon incorporated the Imperial Sugar Co. to be the corporate

basis for their activities. The Cunningham Sugar Co. at Sugar Land had also gone

into bankruptcy, and both Kempner and Eldridge managed to be placed on its

receivership board. In 1908, they acquired the entire Cunningham operation,

which included large landholdings, substantial production facilities, and a

common carrier railroad, the SLRy. They continued to operate Cunningham

Sugar Co. separately until they merged it

into Imperial Sugar in 1917.

In 1907, Eldridge chartered the Imperial Valley Railway (IVR) to build a line from

Sugar Land to Hempstead (which it never reached.) Track-laying began at

Sartartia in November, 1907; five miles of track to reach plantation land at Cabell opened shortly thereafter. In 1912, Eldridge sold the IVR to the SLRy,

effectively an internal transfer of assets. Reed says that the

sale was "...twelve miles of trackage extending from Sugar Land to

Cabell...", so it may have included some temporary tracks serving cane

fields; Cabell is less than half that distance from Sugar Land. Although

the tracks had existed for several years, the IVR had never reported its

construction to RCT. SLRy filed a report with RCT in 1912 recording 4.9 miles of

construction from Sugar Land to Cabell, but this actually was the earlier

construction by the IVR. The SLRy expanded farther north with twelve miles

of track from Cabell to Hickey reported to RCT in 1931.

|

South Texas sugar cane production

was of interest to the Texas State Penitentiary. After the Civil

War, the State had begun leasing convicts to employers who needed low

cost labor. The State justified the program by the revenue generated and

by the fewer number of inmates it had to feed, clothe and house in its

overcrowded prisons; employers were responsible for the care and

security of the inmates they employed. In late 1877, Cunningham had

teamed with Captain Ellis on a five year lease for inmates to work their cane

fields at Sugar Land and Sartartia. The lease proved to be very profitable, so much

so that the Legislature began to question the entire structure of the

convict leasing system. Why couldn't theses profits be going to the

State?

The lease held by Cunningham and Ellis was not renewed in

1883. Instead, the State began to develop its own farms, for sugar cane

and for other crops. To this end, the State purchased the Harlem

Farm in 1885, a sugar cane producer and long time user of convict labor.

It was located a few miles northwest of Sugar Land where today, the

Jester Units of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice are located.

In January, 1908, the State made an

enormous acquisition of

cane field acreage from multiple plantations near Sugar Land, including all

5,900 acres of the Sartartia Plantation. The land would be worked by

prison inmates and the cane would be sold to sugar producers. The mills, refineries and

common carrier railroads owned by the sugar companies were not

part of the sale, but private tracks, locomotives and railcars were

included.

Convict

leasing for any purpose was phased out by the end of 1912 -- the State

itself would henceforth be the exclusive employer of inmates. |

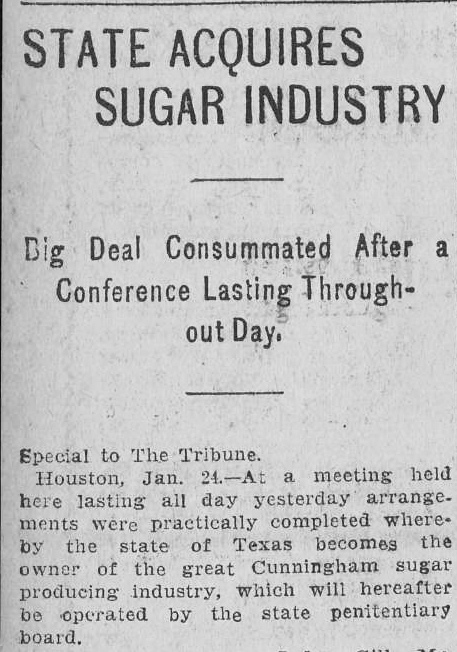

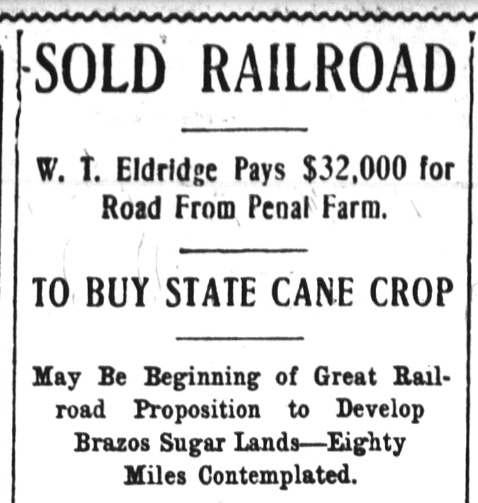

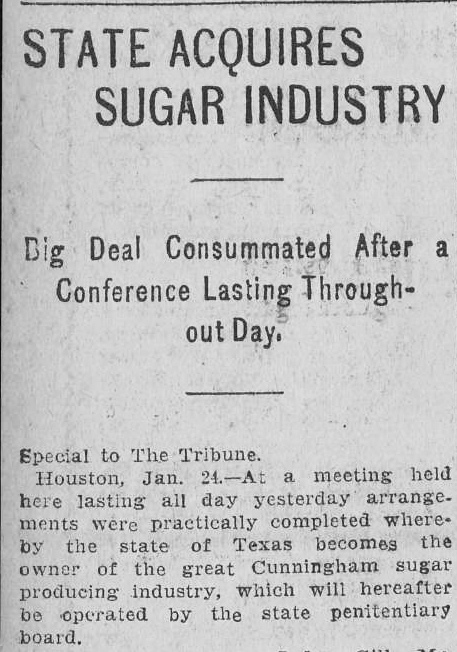

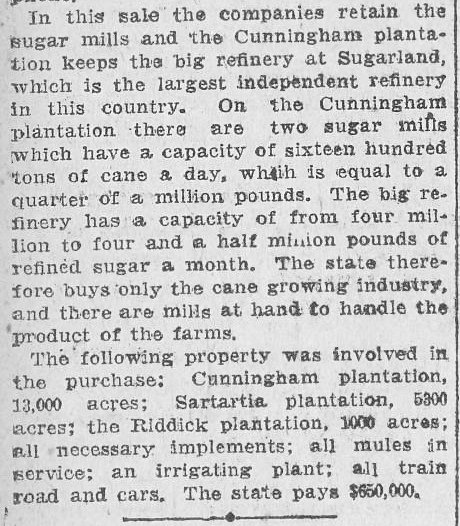

Far Left and Above:

These are the beginning and ending paragraphs of a lengthy story from the Galveston Tribune

of January 24, 1908. The State was increasing its capacity to produce

sugar cane, and the sugar companies agreed to buy the crop. |

|

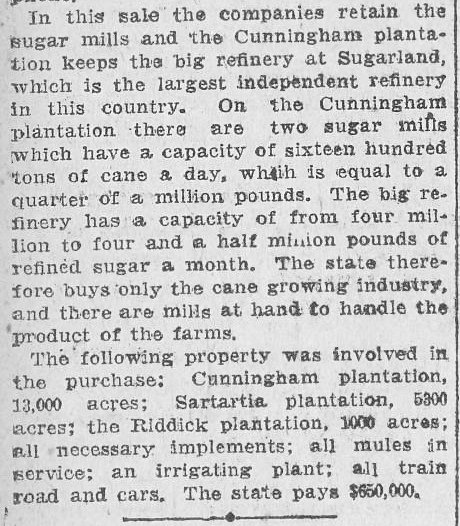

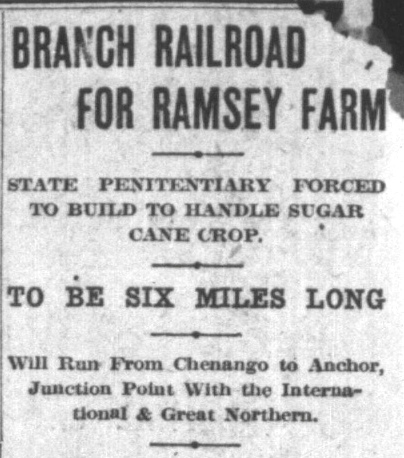

The State's land-buying binge continued later in 1908

as it

acquired the 7,700-acre Ramsey Farm, about twenty

miles south of Sugar Land. Eldridge offered to have the SLRy build a six-mile

rail line from Ramsey Farm to Anchor to give the State a rail outlet on

the I&GN.

Eldridge was already planning to extend the SLRy to Anchor; he would

simply build the last segment first. The State accepted the offer, but

the contract required Eldridge to pay the State $15,000 if he failed to

complete the project within the contract schedule. Eldridge agreed, but

soon had a change of heart. In July, 1908, he abruptly paid the State

the $15,000 penalty and notified them that the SLRy was no longer involved in the project.

Left:

When Eldridge backed out, the State decided to build its own rail line

to Anchor (Fort

Worth Record and Register, August 17, 1908)

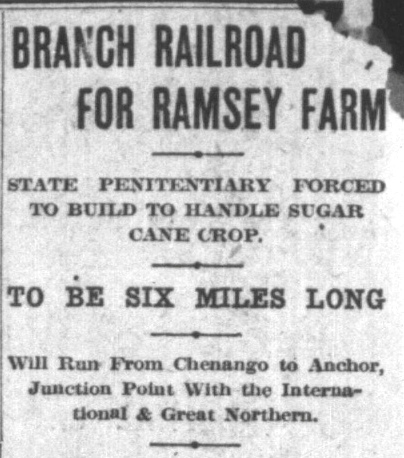

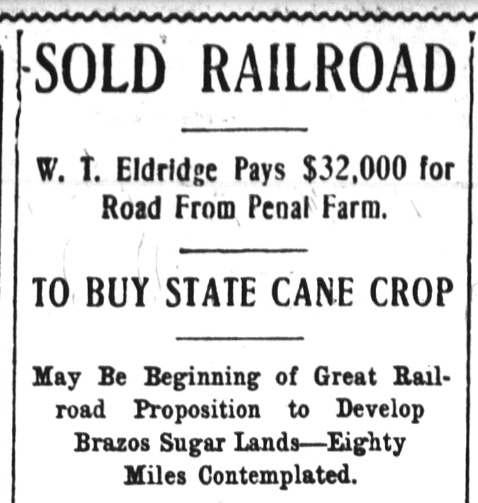

Right: With yet

another change of heart, Eldridge bought

the State's new rail line and agreed to buy the cane

crop produced at Ramsey Farm. Eldridge had decided to proceed with

building to Anchor to facilitate importing Cuban cane via the Port of

Velasco. He could also import Mexican cane through Angleton,

four miles from Anchor, which had a rail connection to Brownsville. (Houston

Post, September 7, 1909)

Today, Texas' Ramsey

Unit prison is located on land of the former Ramsey Farm. |

|

As Eldridge was engaged with the

Ramsey Farm project, the Arcola Sugar Plantation was placed on the

market in 1908 by the Trustee of the bankrupt estate of T. W. House. The

plantation's land, south of the Cunningham property and north of Ramsey Farm,

was owned by the Arcola Sugar Mills Co. which had been incorporated in 1903 when

the plantation was reorganized by the House family enterprise (House had died in

1880.) The bankruptcy stemmed from the collapse of the family's other

investments, so the sugar company was a valuable asset to be sold for the

benefit of the estate's creditors. To offer the plantation for sale, the estate

produced a prospectus (hat tip, John Walker)

that included a map of the

plantation. Among various details, the map showed that as of 1908, plantation tracks had not yet crossed the Santa Fe. The prospectus also noted that in addition to

I&GN, Santa Fe and SLRy tracks built on its property, the

plantation had three miles of standard gauge private tracks from its

headquarters at House to the vicinity of Santa Fe's tracks.

|

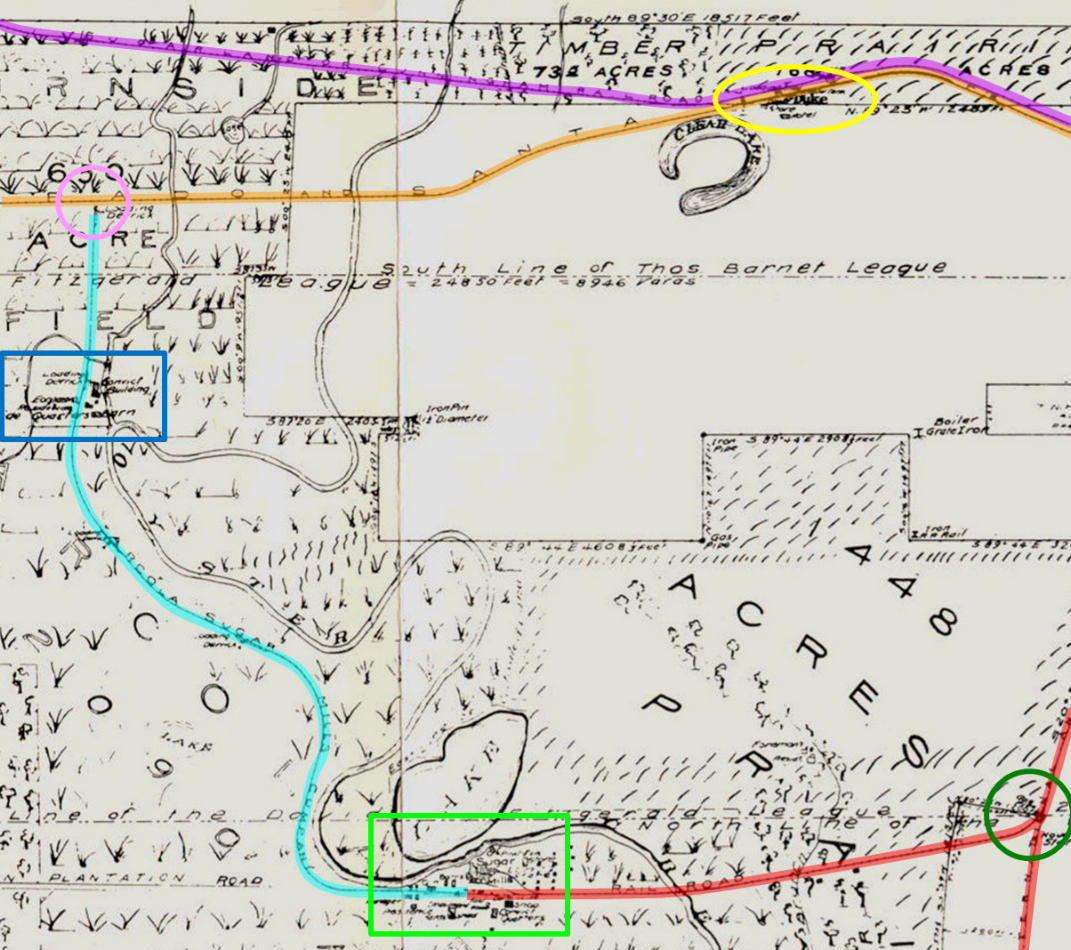

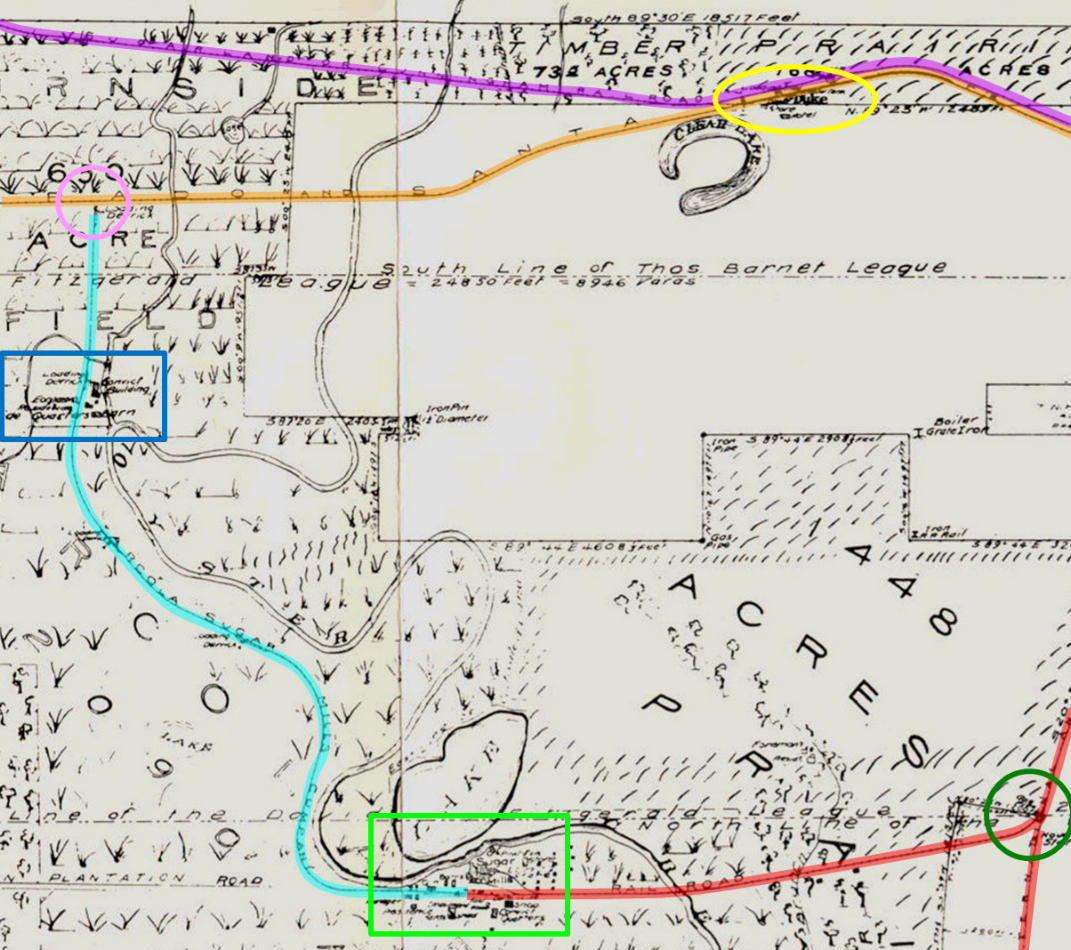

Left: This image snippet is from a 1908 map

included in the prospectus of the Arcola Sugar Plantation, adapted from

an earlier map drawn by the surveyor of Fort Bend County in 1890.

Purple Line: SLRy

tracks to Duke, continuing east to Arcola Junction

Orange

Line: Santa Fe tracks from Galveston through Arcola Junction to Duke,

continuing west to Richmond

Pink Circle: future site of Sugar Land Junction

(Tower 162)

Light Blue Line: private tracks of the Arcola Sugar Mills Co.; note that the tracks reach but do

not cross Santa Fe's tracks

Green Rectangle: House's Sugar House, the

plantation headquarters and main sugar refinery

Blue Rectangle: another sugar house on the

property

Yellow Oval: the community of Duke

Green Circle: Hawdon (also known as "Arcola"), the

House spur's junction with the

Columbia Tap

Red Line:

The I&GN Columbia Tap and the spur west from Hawdon to House's Sugar House |

|

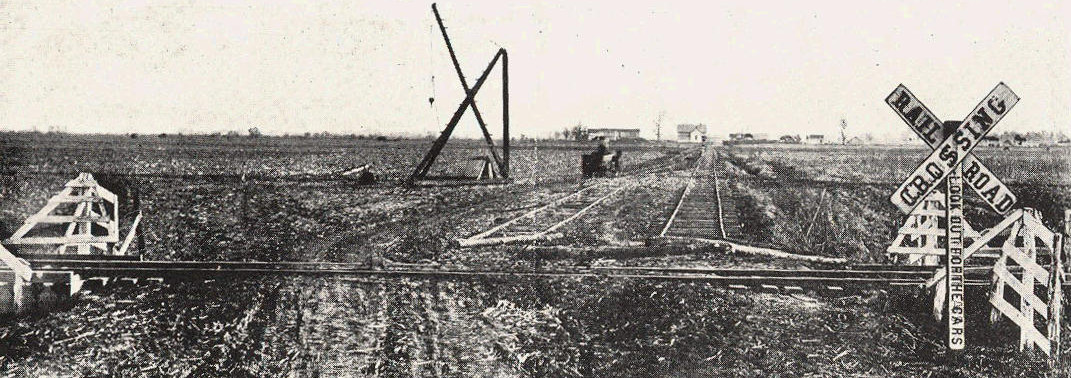

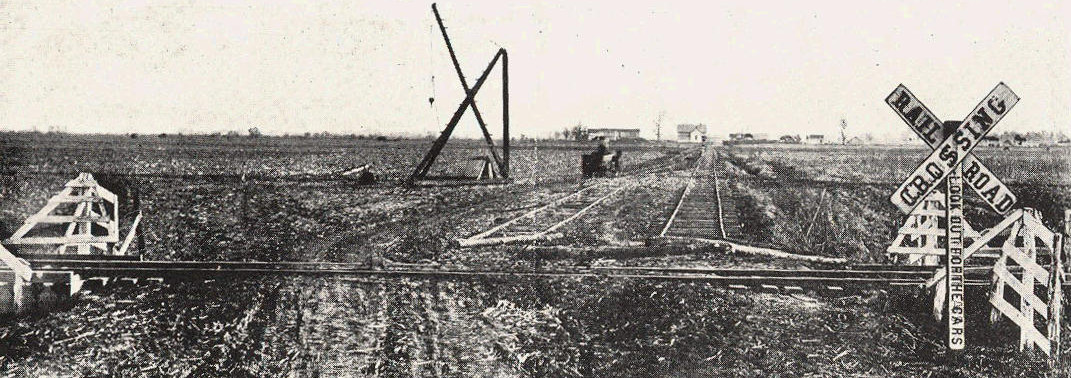

Right: This photo in

the prospectus faces south, looking across the Santa Fe tracks where the

future Sugar Land Junction (pink circle above) would be located. The

prospectus states that its private tracks

run to within "a few feet of the Santa Fe track". Literally. |

|

|

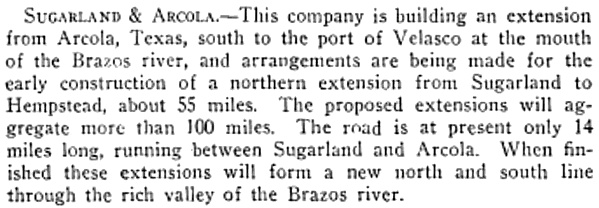

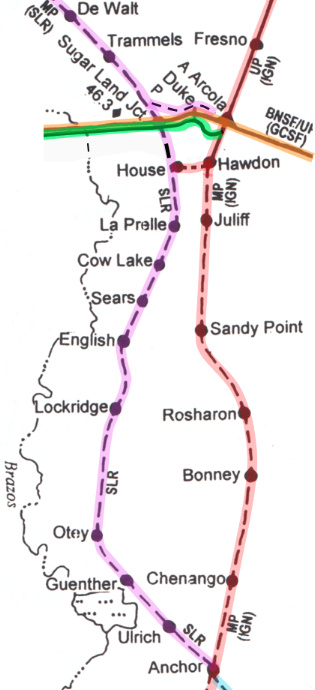

Left:

The Railway Age Gazette of

March 24, 1911 carried this news item regarding the plans of the

Sugarland Railway to build south to Velasco and north to Hempstead.

While both of those destinations were "goals", neither of them was

particularly concrete. Railroads were notorious for announcing grand

plans that were rarely fulfilled. The evidence shows that after Eldridge

acquired the tracks between Ramsey Farm and Anchor, he worked diligently

to establish a new main line between Sugar Land and Anchor. This news

item was undoubtedly in response to a press release from Eldridge, but

why issue one at this particular time? This was around the time that the

SLRy applied to RCT to abandon the last 3.5 miles of track into Duke and

Arcola Jct. The RCT commissioners surely read

Railway Age Gazette so Eldridge may

have wanted them to be aware that he had a grand plan for which a key

step was to avoid the expense of maintaining unnecessary tracks to

Duke and Arcola Jct. |

Determining the means and timing by which Eldridge

accomplished his goal of completing a new main line between Sugar Land and

Anchor is not straightforward because the construction reports submitted to RCT

are inconsistent with other evidence of how Eldridge's plan was executed. The

baseline knowledge, as the prospectus shows, is that in 1908, there were no

tracks crossing the Santa Fe line on the Arcola Plantation except for the I&GN

at Arcola Junction. The passage below from an article in the

Handbook of Texas about the SLRy helps to

explain the most likely scenario of how Eldridge accomplished his goal of

building across the Santa Fe line and continuing far enough south to reach the

tracks he had bought from the State between Ramsey Farm and Anchor.

In 1912 the railroad purchased seventeen miles of private track,

from mile post 10.74 to Rotchford, from the Cunningham Sugar Company. This gave

the Sugar Land Railway Company a new connection with the International and Great

Northern, and the four miles between mile post 10.74 and Arcola were abandoned.

First and foremost, the passage states that the buyer

of "seventeen miles of private track" was "the railroad" (SLRy) and the seller of the

private track was "the Cunningham Sugar Company." Both of those

companies were owned by the Eldridge / Kempner partnership and managed by Eldridge, hence this was effectively an

internal accounting transfer within Eldridge's sugar enterprise. It also had

some legal ramifications because SLRy was a common carrier railroad.

This meant that whatever shipping rates it offered to the Cunningham or Imperial

companies over the newly acquired tracks, it also had to offer to the Arcola Plantation and any other

businesses or passengers it served.

There's no doubt that the citation

to 1912 comes from a construction report submitted to RCT by the SLRy. Since the

SLRy had "...purchased seventeen miles of private track...",

it presumed an obligation to report the tracks to RCT (but whether this was an

actual RCT requirement is undetermined.) As private tracks, the

construction had not been reported, but they were now under the SLRy's common

carrier ownership. The SLRy chose to make the report in 1912, but that doesn't

imply that the purchase actually occurred in 1912 nor does it say anything about

how long the SLRy had been using the tracks. The purchase was an internal

accounting transfer within the Eldridge sugar enterprise, and it is doubtful

that submitting a construction report to RCT was an administrative priority. [For instance, it was not until

1916 that the tracks Eldridge had bought from the State in 1909 (between Ramsey

Farm and Anchor) were reported by the SLRy, even though they constituted part of

this new main line!] The evidence suggests that the SLRy was operating the

seventeen miles at least by early 1911. In the spring of 1911, the SLRy requested permission from RCT to abandon the last 3.5 miles of track to Duke and

Arcola Jct. This request would not have been made unless well before then, the

SLRy had established alternate interchange points for Santa Fe and the I&GN (and

was using them!)

Right: area map, SPV 2001, Mike Walker

In the upper left corner of

the prospectus map (further above) the SLRy passed through the Burnside

production area of the Arcola Plantation, hence the large letters "R N S I D E"

appear on the map cropped from the original, larger map. A short

distance south of the Burnside convict camp at a point where

the SLRy tracks shifted to a 95-degree east heading (toward Duke) the

SLRy established a stop for House passengers where a dirt road led

three miles south to House. The stop became christened Burnside Switch

when a switch was installed for construction of a new track going south

across the Santa Fe to connect with the Arcola Plantation's private

rails. A timetable for the SLRy shows Burnside 10.7 rail miles from

Sugar Land, hence Burnside Switch was "mile post 10.74"

cited twice in the Handbook article.

Beginning at Burnside Switch, Eldridge built tracks that crossed the Santa Fe line in the first mile. This eventually became Sugarland Junction, the site of

the SLRy's new interchange track with Santa Fe. It was also where

Eldridge connected to the three miles of private track to House

Junction. The I&GN spur from Hawdon ended at House Jct., which

became the starting point for the tracks Eldridge built south to Rotchford,

cited in the article. Presumably, Rotchford was at, or near, the north end of the tracks

Eldridge had bought from the State in 1909. An SLRy timetable shows

Rotchford 0.7 miles

south of Otey, a little less than six miles from Anchor, but it

does not appear on Mike Walker's map at right (nor does Burnside

Switch.)

All of this track construction (plus the three miles of existing

private track) was assigned by Eldridge to Cunningham Sugar. The distance from Burnside Switch to House

Jct.

was a little over three miles and the total purchase was seventeen miles, hence the distance from House

Jct. to Rotchford should have been a little less than

fourteen miles. The aforementioned 1912 construction record submitted to RCT

lists a 13.62-mile segment between Arcola and Ratchford

(a slightly different spelling) that fits the expected distance.

Arcola was the original name for the plantation headquarters (House

had been adopted during the T. W. House era.)

A Joint Facilities

Record for Sugarland Junction dated June 1, 1975 (hat tip, Santa Fe

Railway Historical and Modeling Society) states that a contract between

Santa Fe and the SLRy covering an interchange track in the northeast

quadrant is dated October 16, 1911. This is consistent with the

proposition

that the SLRy had been operating over the Cunningham Sugar tracks in

1911, and probably earlier. The October, 1911 contract was simply documenting

the SLRy's new

ownership (again, an argument for the "purchase" being before 1912.)

Presumably, Santa Fe had an earlier interchange agreement with

Cunningham Sugar, and this was a revision to update the track ownership.

Summarizing, Eldridge bought three miles of private track on the Arcola Plantation

that ran between Sugarland Jct and House Jct.

He built new tracks from Burnside Switch to Sugarland Jct. and new

tracks from House

Jct. to Rotchford, probably in 1910. The tracks were assigned to

Cunningham Sugar, but SLRy operated over them through some kind of internal

arrangement (e.g. a contract to operate them for Cunningham Sugar, or

perhaps a lease.) At some point, probably in 1911 or 1912, the SLRy

officially bought the tracks from Cunningham Sugar and declared Anchor

to be the new endpoint of its main line from Sugar Land. The SLRy sought RCT permission to abandon the tracks between Burnside Switch and Arcola Jct., and was

sued by the State in July, 1911 for removing those tracks. |

|

The October, 1913 issue of

Railway Age

Gazette (hat tip, Bill Willits) reported the outcome of the

lawsuit against the SLRy for abandoning the tracks to Arcola Junction.

“The State of Texas has lost

its case against the Sugarland Railway Company for penalties amounting to $5,000

and a mandatory injunction to compel the road to rebuild a short branch which

had been torn up and which the railroad claims would have cost $40,000 to

construct and $10,000 annually to maintain, with practically no revenue. The

case was filed in July, 1911, shortly before the company had extended its line

from a point three miles from Arcola Junction to a point eighteen miles south of

the connecting point of the International & Great Northern and the Santa Fe,

leaving a spur 3 1/2 miles long from the point of divergence of the extension to

Arcola Junction. Permission was granted by the Railroad Commission to tear up

the spur, but later the order was revoked, and the company was ordered to

rebuild the track.”

Breaking down this news item... the

"...spur 3 1/2 miles long from the point of divergence of the extension to

Arcola Junction" is the SLRy's original main track

to Duke and Arcola Junction. It was never an extension, and was not a spur until SLRy began using

the line from Burnside Switch ("the point of divergence") to House

and Anchor as

its main line. Since Burnside Switch was approximately mile post 10.7 and the total

distance to Arcola Junction was 14.2 miles, the article is correct that the length of the spur was 3.5 miles. That the tracks to Duke and Arcola Junction had become

relegated to spur status and were seeing so little traffic that the SLRy wanted to (and

actually did!) remove them implies that the service through Sugar Land Junction

to House Jct. must have begun at least some

reasonable period of time (e.g. 1910) before the spur's removal in 1911. The

SLRy would not have abandoned its Santa Fe and I&GN interchange points unless it

had established (procedurally and contractually) new connections with those

railroads. RCT's permission "...to tear up the spur..."

was granted on June 24, 1911. Wasting no time, the SLRy accomplished the

task prior to July 3, 1911 when RCT rescinded the permission.

The article confusingly (but accurately!) states that the SLRy "...had

extended its line from a point three miles from Arcola Junction to a point

eighteen miles south of the connecting point of the International and Great

Northern and the Santa Fe..." That "connecting point"

was Arcola Jct., i.e. the sentence could have

been written "...from a point three miles from Arcola Junction to a point

eighteen miles south of Arcola Junction..." Unless the subject was

the Columbia Tap, such a sentence would appear to make little

sense. But the article doesn't say that the SLRy

built eighteen miles, only that it terminated

at "a point eighteen miles south of..." Arcola Junction. And that was,

in fact, where the SLRy terminated -- at Anchor --

eighteen miles south of Arcola Jct. Once the private track purchase

had been consummated, the result was a continuous line -- the new SLRy main line -- from Sugar Land

to Anchor. The reference to "three miles from Arcola Jct."

was a round off of the distance to Burnside Switch. The Handbook of Texas

rounded up stating "...the four

miles between mile post 10.74 and Arcola were abandoned...". The

Handbook article was almost certainly

sourced from a statement in Reed's book ..."In 1912, about four

miles of trackage, from Arcola north, was abandoned." It was 1911, not

1912, and the north reference meant "toward Sugar Land" which was

northwest of Arcola Junction.

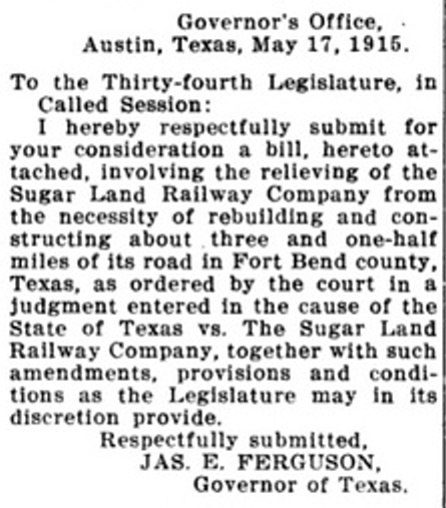

The State of Texas appealed the court ruling. In 1914, the

appellate court reversed the trial court and ruled in favor of the State. The

legal theory was that RCT had no power to abrogate an element of a railroad's

state law charter

which in this case required SLRy to have a line to Arcola Jct. (it was the only

rail line identified in the SLRy charter.) Evidence in court showed that the line to Duke and Arcola

was seeing so

little use that "...its ties had rotted, and its rails rusted...",

but the ORG says the

line had been in use in 1908. Service likely continued for

at least a couple of years while the new SLRy main line via House Jct. was

established. Eldridge planned to abandon the tracks to Arcola Jct. so he

had merely deferred maintenance. The SLRy claimed the "...abandoned line served only one person..." who

still had rail service from the adjacent Santa

Fe line! Yet, the ruling went against the SLRy, so it immediately began

working the political angle to have the Legislature overturn the court's

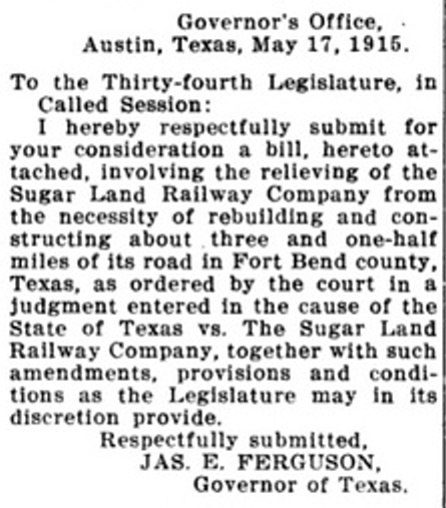

decision. No evidence has been found to indicate that the law proposed by Governor Ferguson (right)

ever passed.

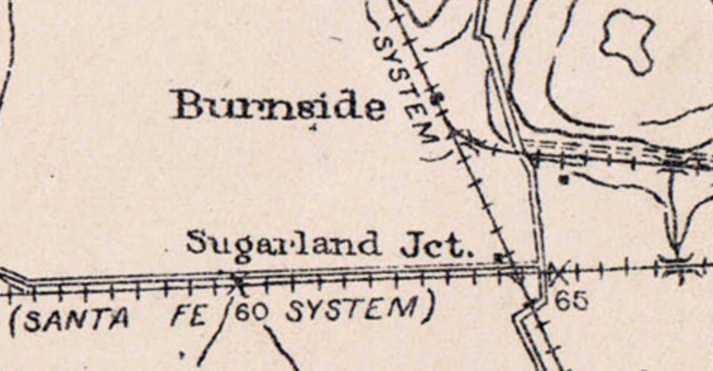

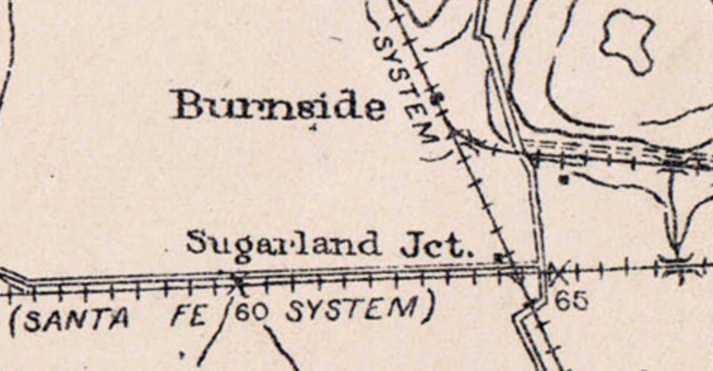

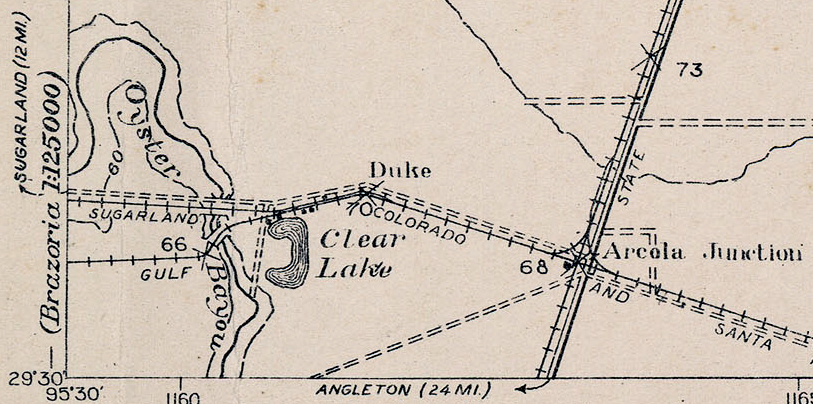

Below Left: Sugarland Junction

appears on this 1929 "redraw" of a 1915 USGS topo map. The "System"

label near Burnside comes from "Missouri Pacific System", which in 1925

had acquired the SLRy (proving this was a map update, not simply a

redraw.) The map does not show any

connections at Sugarland Junction, yet one is known to have existed in

1911 and is documented in a 1915 Santa Fe

Mileage Statement.

Below Right:

The 1929 "Pearland" quadrant topo map shows the SLRy tracks intact to

Duke but they do not extend to Arcola Junction.

There is, however, a new northwest connector at Arcola Jct. between the

Santa Fe and I-GN. It's likely that SLRy negotiated trackage rights between the connector and Duke

to satisfy its charter requirement to serve Arcola Jct. (Perry-Castaneda

Map Collection, University of Texas)

The gist of these maps is that at some point prior to 1929, the SLRy line to Duke had been

rebuilt, but did not continue to Arcola Jct. That no connecting track is shown at Sugarland Jct. suggests

that it

had been removed as duplicative of the reinstated connection at Duke. A

1932 MP timetable shows SLRy service through House Jct. to Anchor, but

does not show service to Duke. |

|

|

|

|

Left:

(1930 aerial imagery, (c)historicaerials.com) Coming south from

Sugar Land Jct., the original private track to House (yellow arrows)

curved west to avoid Oyster Creek. It then looped back east, staying

south of the creek to reach the sugar mill at House and (in 1894) a

direct connection into the I&GN spur from Hawdon. It seems likely that

wye tracks (red arrows) were built so that trains on the spur from

Hawdon could turn around. This became House Jct. (pink circle) from

which the track southward to Anchor departed. At some point, a new track

(green arrows) and switch (blue arrow) were built north of the wye.

Perhaps SLRy wanted a straight line in this area instead of multiple

curves for its trains serving Anchor. Due to the lack of north side

connectors at House Jct., the straight track did not directly support

southbound service to House and Hawdon.

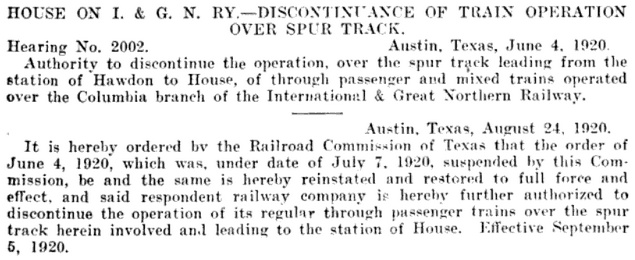

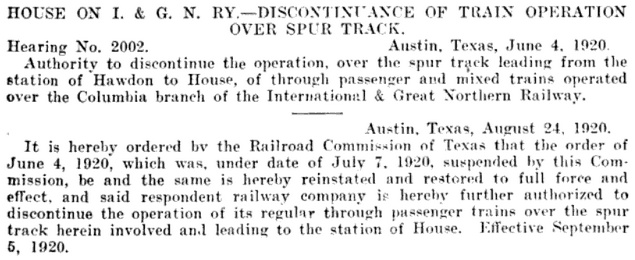

Above: In June, 1920,

RCT granted permission for I&GN to stop passenger and mixed train

service over the spur from Hawdon to House. The permission was suspended

in July but reinstated in September covering "...regular through

passenger trains...". I&GN had been making the 1.9 mile run from Hawdon

to House with various passenger and mixed trains since 1894. RCT granted

the permission because SLRy served House and Hawdon.

In 1924,

Missouri Pacific (MP) tried to buy the I-GN but the sale was denied

by the

Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC.) Instead, the I-GN was bought

by the

New Orleans, Texas & Mexico (NOT&M) Railway, a sale vigorously and

publicly opposed by Eldridge. The NOT&M had been re-chartered to be the

parent company of the Gulf Coast Lines (GCL), a collection of

coastal railroads that

had been owned by the much larger St. Louis & San Francisco

("Frisco") Railway

prior to its bankruptcy in 1913. In purchasing the I-GN, the NOT&M was

acting as a proxy for MP. In 1925, the ICC allowed MP to acquire the NOT&M

and all of its subsidiary railroads including the I-GN. MP then acquired the

H&BV (1925) and the SLRy (1926.) All of these railroads were

dissolved and merged into the MP system in 1956. MP was acquired by

Union Pacific (UP) in 1982 and fully merged in 1997. |

A March, 1925 SLRy timetable advertised mixed train

service from Sugar Land to House that continued through Hawdon to Houston using I&GN

trackage rights. By 1927, both railroads were owned by MP, and the service

changed so that the SLRy no

longer operated into Houston. Instead,

the SLRy timed its Hawdon arrivals and departures to

coincide with I-GN trains to and from Houston. Reed's book states that

as of January, 1940, the SLRy "...has a trackage contract with the I. &

G. N. under which it may operate trains to Houston...", but it

does not appear to have been exercising those rights.

Eldridge built the

line to Anchor to

realize the benefit of a direct connection with the H&BV for Cuban sugar cane

imports through Velasco. But Anchor was only four miles from Angleton where a

connection could be made with the St.

Louis, Brownsville and Mexico (SLB&M) Railway, one of the GCL railroads.

The SLB&M line south from Angleton went to Brownsville, which had a rail bridge

into Mexico. Thus, importing Mexican sugar cane was also part of Eldridge's

plan. The June, 1911 issue of the American

Sugar Industry and Beet Sugar Gazette reported that the SLRy had amended

its charter to extend its tracks from Anchor to Angleton for a direct connection

with the SLB&M (to eliminate the 4-mile H&BV haul) but the extension was never built. And

once the railroads at Anchor were under common MP ownership, cane shipments from

Mexico (via Angleton) or Cuba (via the Port of Velasco) did not need to take the

SLRy tracks from Anchor through Otey and House Jct. to reach Sugar Land. The cane cars could be

taken north from Anchor on regular I-GN freight trains to be left at Hawdon for

SLRy trains to take to Sugar Land. Thus, there was no need to retain the SLRy tracks

between Anchor and House, and they were formally abandoned in 1932. Since those

tracks passed through Ramsey Farm, it's possible that a portion of the line was

retained by the State prison system.

The State's 1908 construction of the tracks from Ramsey Farm to Anchor had

never been reported to RCT, so SLRy did so in 1916 (although it had bought the

tracks in 1909.) This is one example of why construction reports submitted to

RCT have inaccuracies,

for a variety of reasons. Since RCT did not exist until 1891, there was no reporting requirement

until then. The reports RCT has from earlier years were compiled by

its staff using historical resources, no doubt full of errors and omissions.

Even after 1891, railroads sometimes failed to submit reports, or submitted inaccurate information. One common

error was to attribute construction to a particular year, even if most of the

work was done in prior years. Some railroads didn't report until a major segment

was complete regardless of the years involved. Others reported yearly progress

by milepost.

The SLRy construction reports compiled by RCT (of which the

post-1956 actions were executed by MP) are as follows:

1894 Sugar Land to Arcola Jct

14.2 miles

1912 Sugar Land to Cabell

4.9 miles

1912 Arcola to Ratchford

13.62 miles

1916 Otey to Anchor

6.22 miles

1931 Cabell to Hickey

11.94 miles

1932 Anchor to House

21.13 miles abandoned

1942 Cabell to Hickey

11.66 miles abandoned

1952 Cabell to Pryor

3.51 miles abandoned

1981 Hawdon to Herbert

12.1 miles abandoned

1985 Sugar Land to Pryor

0.95 miles abandoned

In the mid 1920s, SP decided to make its Texas &

New Orleans (T&NO) Railroad subsidiary the principal operating company

for SP lines in Texas and Louisiana, hence the GH&SA was leased to the T&NO in

1927. GH&SA employees were gradually transferred to T&NO, and the GH&SA

locomotives and rolling stock were eventually converted to the T&NO paint and

numbering scheme. The GH&SA was merged formally into the T&NO in 1934 and the GH&SA name

was retired.

|

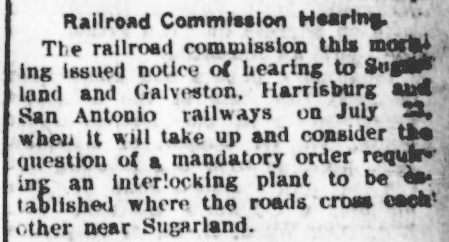

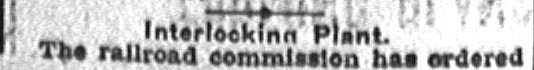

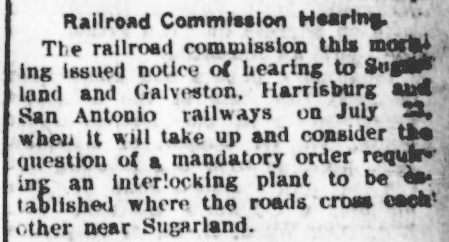

Left: The San

Antonio Daily Light of July 17, 1903 reported that a hearing

had been scheduled by RCT to consider whether to order an interlocking

plant for the SP / SLRy crossing at Sugarland.

Right: Mistakenly citing "Brazoria

county" instead of "Sugar Land" (in Fort Bend County) the September 5, 1903

Austin Statesman reported the unusual news that RCT had

mandated a cabin interlocking plant for the SP /

SLRy crossing. |

|

Notwithstanding the report of the

Austin Statesman above, RCT's order for a Sugar

Land cabin interlocking was never executed; presumably the order was rescinded

at the behest of the railroads. This was the first known order by RCT to require

a cabin interlocking. The first actual cabin interlocking installation would not

occur for another dozen years, at Magnolia Park in

1915, and it was not until the 1920s that cabin interlockers became common in

Texas. Cabin interlockers were useful for rail intersections where a

light-traffic line (here, the SLRy) crossed a busy line (the GH&SA.) Cabin

interlockers were popular with

railroads because they saved money by eliminating the need to staff a tower --

the labor to operate cabin interlockers was supplied by train crews on the lightly used line.

Every train on that line would stop at the diamond and a crewmember would enter

the cabin to change the signals and derails to permit his train to cross the

busier line. Once the crossing was complete, the crewmember would reverse the

controls to allow unrestricted movements on the busier line and then return to

his train. Trains on the busier line would never see a STOP signal unless

they happened to approach the crossing while it was in use by the other railroad.

Prior to the installation of an interlocker, it is likely that the Sugar Land

crossing was gated, with the gate normally positioned against the SLRy.

Despite RCTs early interest in the Sugar Land crossing, it did not

return to that subject until 1922 when it authorized plans for a manned, 2-story

interlocking tower. Tower 114 was commissioned

for operation at Sugar Land on April 30, 1923 with an 11-function electrical

plant located on Imperial Sugar Company property. It was

undoubtedly built by SP, and RCT's annual interlocker summary notes that the

tower was operated by GH&SA employees. Despite the camera distance in the aerial view at top of page, the tower

resembles other SP towers in Texas (e.g. Tower

115 at Eagle Lake which opened the following year.) In the vast majority of

cases, the company that staffed and maintained a manned tower was also the one

that had built it.

|

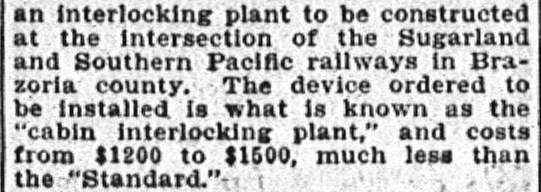

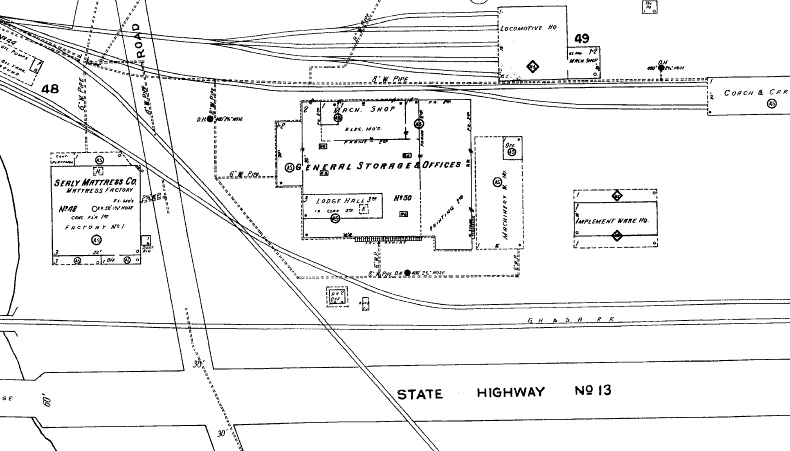

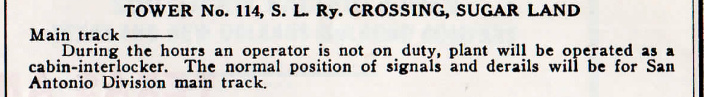

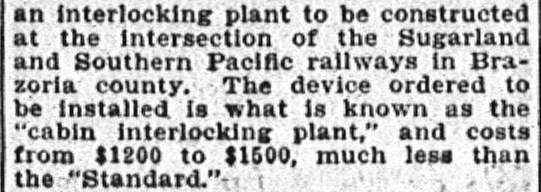

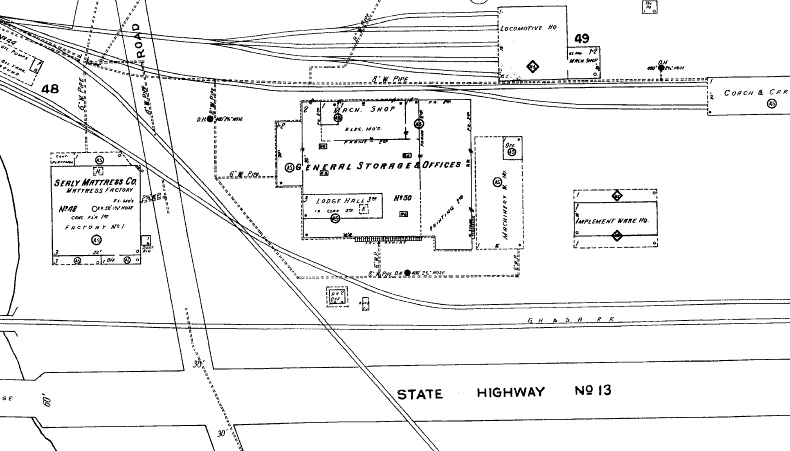

Left:

The 1926 Sanborn Fire Insurance map of Sugar Land shows Tower 114 at the

GH&SA / SLRy crossing.

It also shows a lengthy connecting track that "behind" the tower, i.e.

on the opposite side of the windows facing the diamond.

Above: Magnification

shows the cartographer documented the tower as a 2-story "R.R. Off."

(railroad office) with a door

(x) on the southeast corner and an internal staircase (1-2) in the

southwest corner. The dashed line surrounding the tower indicates an enlarged roof overhang. A storage shed for maintenance

supplies and equipment was located adjacent to the tower. |

|

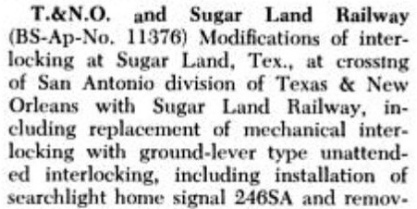

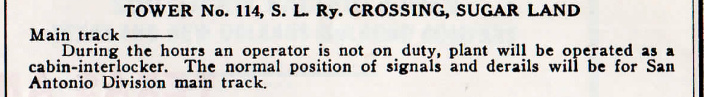

Right: This excerpt from a 1939 T&NO employee

timetable (ETT) notes that when the tower was not staffed, the crossing

would be treated as a cabin interlocker, i.e. the last operator on duty

would set the controls for unrestricted SP movements. At such times,

whether MP crewmembers entered the tower

to operate the controls or called a standby operator to do so is

undetermined. |

|

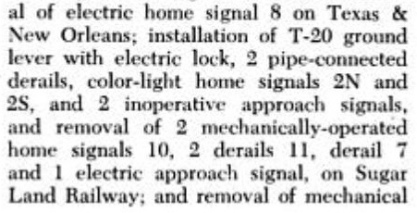

Above: Plans to modify the

Tower 114 interlocker were advertised in the September, 1950 issue of Railway Signaling and

Communications. Among the changes were the replacement of the

mechanical interlocking with a "ground-lever type unattended interlocking" along

with numerous signal and derail modifications.

A note from 1951 in Vol. 68 of Trains-Communicator

(a

newsletter of the tower operators union) states... "The gang is at Sugarland

putting in the automatic crossing which means the end of Tower 114 and probably

a couple operators." The fate of the tower building is undetermined.

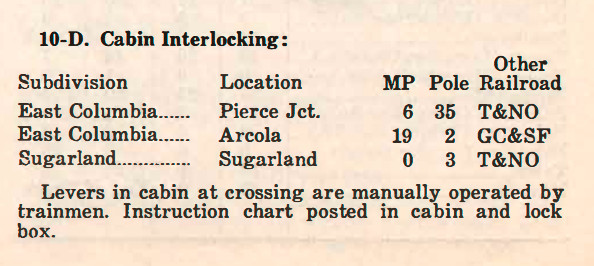

In 1930 on July 16 and 22, respectively, cabin

interlockers were commissioned at Arcola Jct. (Tower 161) and Sugarland Jct.

(Tower 162.) The mechanical plant at Arcola Jct. had twelve functions, a typical

minimal interlocking with a home signal, distant signal and derail in each of

the four directions. Switches for the connecting track(s) at Arcola Jct. were

not part of the interlocking plant. RCT listed Sugarland Jct. with 26

functions and a "Mechanical - Electrical" plant. The substantially

larger function count pertained to switches, signals and derails for the

interchange track and the main line siding to which it connected. The

final publication of RCT's annual summary of active interlocking towers in Texas

was dated December 31, 1930. Tower 162 was the last entry in the list for

which a commissioning date was also provided. The remaining interlockers in

that list (Tower 163 at Sealy through

Tower 170 at Conroe) were shown as "Under

Construction." The interlocking tower count had reached

215 by the time RCT stopped managing

interlocking plants in Texas in the 1960s.

Above Left: Looking east, BNSF

crosses the Columbia Tap at Tower 161 and then crosses Farm Road 521 in quick

succession. (R. J. McKay photo)

Above Right: This

Tom Kline photo shows an unlocked and opened Tower 161 override control box

and its posted instructions. The original cabin is no longer present and the

interlocking plant is now fully electronic with override controls mounted on

posts at the crossing. Below: With evidence

of a rare snowfall, this January, 2025 Google Street View shows the

override controls mounted on two side-by-side posts, one for each railroad. The

interlocking is automatic; the override controls are used to "fix" the

signals when necessary. The equipment cabin houses the interlocking plant, but

access is only for maintenance personnel.

Below Left: This photo was taken along

the SLRy ROW during or shortly after the abandonment of the Tower 162 crossing.

A block signal is visible in the distance (John Treadgold collection.)

Below Right: This aerial image

from 2009 shows the remnant of the Tower 162 interlocker equipment adjacent to

the Santa Fe tracks which cross horizontally in the middle of the image. The SLRy ROW

continues to be used for utility lines.

The track at the bottom of the image is the spur to Smithers Lake built in the

late 1990s (see below.)

|

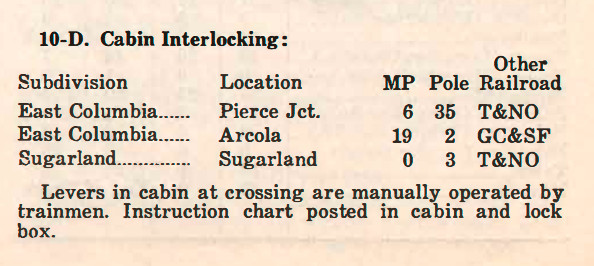

Left: A

Special Instructions bulletin issued on September 15, 1952 by MP for its

I-GN Palestine Division carried this paragraph noting a total of three

cabin interlockers in the Division, all of them in the vicinity of

Sugar Land. Cabins at Arcola (Tower 161) and

Sugar Land (Tower 114, which was converted around this time to a ground-lever

plant) are both listed, and Pierce Jct was

nearby where the Columbia Tap crossed SP's line east of Tower 114. Sugar Land

Junction (Tower 162) is not listed

though it is reported elsewhere in the bulletin as interlocked (but not

automatic.)

It was probably an electronic plant with controls mounted on a post.

The bulletin also has Sugar Land Jct. in a table of Yard Limits with a

total span of two

miles (!) but the reason is undetermined (particularly for such a

lengthy distance.) Aerial

imagery from the 1950s does not show a yard, only a single exchange

track. The interlocker would normally be set to grant unrestricted

movements to Santa Fe, and would have been operated by SLRy train crews

when they needed to cross, i.e. it was a cabin interlocker without the

cabin! A 1951 timetable shows only a single local

freight daily (except Sunday) round trip from Sugar Land to Hawdon. |

The SLRy's northward extension from Cabell to Hickey

was abandoned back to Cabell in 1942. Another three miles south from Cabell to

Pryor was abandoned in 1952. The tracks to Pryor lasted until 1985. The

tracks from Sugar Land to Hawdon via Tower 162 remained intact until 1981 when

MP abandoned the segment between Hawdon and Herbert, which was just over

three rail miles south of the Tower 114 crossing. The former SP main line remains busy, now owned by UP

which acquired and merged SP in 1996. The Santa Fe line remains intact, operated by successor Burlington

Northern Santa Fe (BNSF). The Columbia Tap south of Arcola Junction

was abandoned in stages by MP: south of Anchor in 1956, south of Rosharon in

1962, south of Hawdon in 1987, and (by UP) south of Arcola in 1999.

Smithers Lake

In 1956, Houston Lighting & Power (HL&P) began

construction of a gas-fired power generation plant southeast of Richmond along Dry Creek. The plant

required a source for cooling water, so a new reservoir, Smithers Lake, was

impounded in 1957, increasing the capacity of an existing small lake. There was

already a rail line adjacent to the plant site because in 1930-31, Santa Fe

(through its Cane Belt subsidiary) had built a branch line that

departed the Santa Fe main at the community of Thompsons and went southwest

for 33 miles to a junction with an existing Cane Belt line to serve the massive sulfur deposit at

Newgulf. Reaching it required

crossing an SP line

at Guy that had been built in 1918 to access mineral deposits at Damon Mound.

The Cane Belt / SP crossing was lightly used and never interlocked.

When Smithers Lake added a coal-burning power generation unit in the late

1970s, the branch line gave Santa Fe an advantage in supplying coal to the power

plant. Santa Fe's arrangement with Burlington Northern (BN) had BN bringing coal

trains from Wyoming to Fort Worth where Santa Fe would take over and bring them

to Smithers Lake. Empty trains were sent back to Fort Worth and handed over to BN. The target

round-trip cycle time to Smithers Lake from Ft. Worth was 44 hours, including 4 hours

to unload.

HL&P fought for better rates on coal deliveries through

proceedings with the ICC in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Ultimately HL&P signed long term contracts to use BN and Santa Fe trains to

deliver most of the coal they needed, but they also put out periodic open bids

for additional coal. UP teamed with Chicago & Northwestern to bid successfully

on many of these short term contracts. Since Santa Fe had the only tracks

into Smithers Lake, UP trains were interchanged with Santa Fe at Ft. Worth for

the round trip to Smithers Lake. That HL&P was getting better rates on these

short term deliveries was a major factor in their opposition to the BN / Santa

Fe merger that created BNSF in the mid 1990s. If the merger was to be approved,

they requested overhead trackage rights from Sealy and Rosenberg

to Smithers Lake so that coal trains of competitor railroads could deliver directly to

the plant. It appears that this request was denied because after the merger,

HL&P worked with UP to build a line directly into Smithers Lake from Arcola

Junction, avoiding the need to use BNSF tracks.

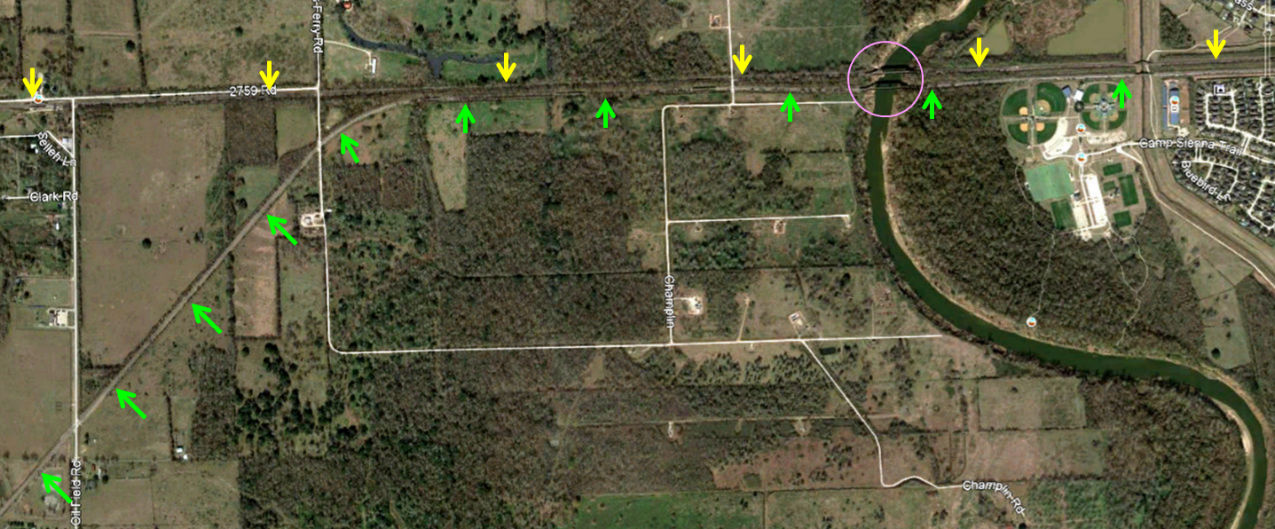

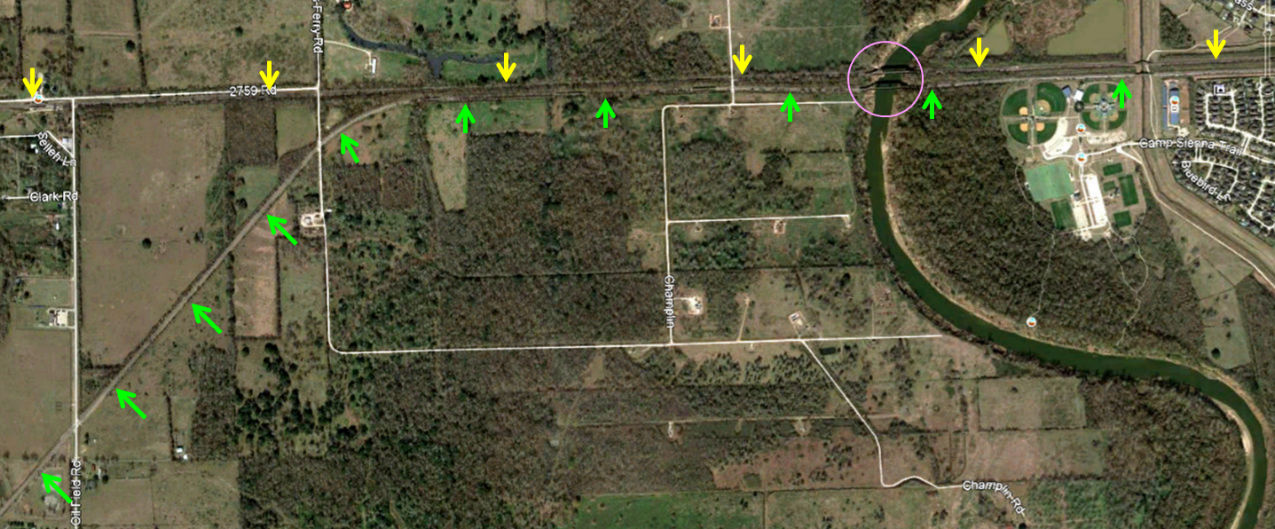

Above:

This annotated Google Maps image shows the HL&P tracks in the vicinity of Arcola Jct.

The balloon track (red loop) off of the Columbia Tap is a more recent addition

(c.2018) to serve a Cemex aggregates yard and ready-mix plant.

The map above shows how UP and HL&P built a new line to Smithers Lake to avoid the

need to use BNSF's tracks. UP rehabilitated the Columbia Tap from the north (red)

down to Tower 161 to be able to carry coal trains, and then added a

sweeping 90-degree curve to the northwest immediately south of the crossing

(while abandoning the remaining Columbia Tap south of the curve.) New tracks

(green) reached the ROW of the BNSF main line (yellow) and continued to the

community of Thompsons (off the map to the left) 4.5 miles west of the former

Sugar Land Jct. The new track then curved southwest to reach Smithers Lake. HL&P

owned the new line and gave UP contracts for coal deliveries. [Deregulation of

the Texas retail electricity market in 2002 resulted in significant breakup and

restructuring of corporate utilities including HL&P; it appears that NRG,

through its subsidiary Reliant Energy, now owns this track.] Ultimately, the

plan did not provide effective competition because UP's routing required coal

trains to transit though Houston to reach the Columbia

Tap, creating delivery

uncertainties and raising costs. By contrast, BNSF coal trains arrived via Fort

Worth, Temple and Rosenberg, completely avoiding Houston. Eventually, BNSF

decided to add their own 180-degree connector to access HL&P's track. This benefited

BNSF by allowing multiple coal trains to be queued over the spur's

10-mile length, keeping parked trains out of the busy main line sidings. Empty

coal trains would continue to depart Smithers Lake using BNSF's tracks directly

to the main line near Thompsons where they turned west toward Rosenberg.

Above: UP's Columbia Tap line (purple arrows) no longer

proceeds south of Tower 161 (pink circle) except for an immediate sweeping curve

that connects (via the red arrow switch) to both the Smithers Lake spur (green

arrows) and the balloon track (blue arrows) serving the Cemex aggregates operation

(built in 2018-2019.) The balloon track makes a tight

loop back to a connection with itself (pink arrow.) The Smithers

Lake spur (built sometime between January, 1995 and April, 2002) reaches the

BNSF ROW (yellow arrows) and follows it west to Thompsons. Satellite imagery shows that by January, 2009, BNSF

had begun building its own

connector from the main line to the spur which required a 180 degree semicircle (orange arrows) to

bring it onto the correct alignment. BNSF's loaded coal trains arrive eastbound

on the main and take this

loop to access the spur. Since the spur is ten miles long, multiple loaded

coal trains can be queued on it, freeing up valuable siding space on the main

line and improving delivery reliability. (Google Earth, December, 2019)

Below: The tracks for the Cemex

facility are between the pavement and the tree line, viewed here from the

entrance on Fenn Rd. The switch for the HL&P tracks (red arrow) is a short

distance off the map to the right. (Google Street View, July, 2022)

Above: West of Sugar Land Jct. the Smithers Lake spur (green arrows) and the BNSF main (yellow arrows) remain

parallel across the Brazos River (pink circle) which required a new bridge for

the spur. Near the community of Thompsons, the spur curves away from the BNSF

main and slants southwest toward the Smithers Lake plant. A

BNSF equipment cabinet at the Oilfield Rd. grade crossing (lower left corner)

implies that BNSF maintains the spur. (Google Earth, December, 2019)

Below:

The spur tracks (green arrows) slant southwest from Thompsons and then curve due

west onto a utility ROW for the final 1.5 miles into the plant. The spur track

merges (at red arrow switch) into the existing plant tracks (blue arrows.) Empty

BNSF trains proceed northeast through the switch on a track (yellow arrows) to

the main line at Thompsons where they proceed west. Thus, there is no conflict

with inbound coal trains. UP's empty coal trains had to depart back to the

Columbia Tap, preventing UP from having any other train on the spur. Graphical maps of this area

have been found showing the utility ROW hosting UP's spur from

Smithers Lake all the way back east to the Columbia Tap, but they are incorrect. UP rails

have never existed on the utility ROW east of the slant track curve. (Google

Earth, December, 2019)

Above Left: The W T Byler Co. supplies this

northeast-facing aerial image of their construction of the BNSF connector loop

(inner loop.)

The outer curved track is the access to the Smithers Lake spur from the Columbia

Tap.

Above Right: With an

impressive number of power lines in view, John Treadgold took this photo of the

Smithers Lake spur's connection to the Smithers Lake plant tracks on July 13, 2020.