Texas Railroad History - Tower 121 - San Antonio (East

Yard)

A Three-Story Interlocking Tower at East Yard of the Galveston, Harrisburg & San

Antonio (GH&SA) Railway in San Antonio

Above: Art Fisher took these

photos of Tower 121 in 2002. The left photo faces the west side of the tower

showing a door and a walkway on the second story. The walkway likely connected to an access point

behind the tower where the staircase

up to the top floor was located. The right photo shows the east face of the tower with a

landing on the third floor, and the north side of the tower facing the tracks.

The staircase came up the back side of the tower and wrapped around to access

the third floor door along the east wall. The signs on the tower show that it

had become associated with Control Point SA208 in Union Pacific's network.

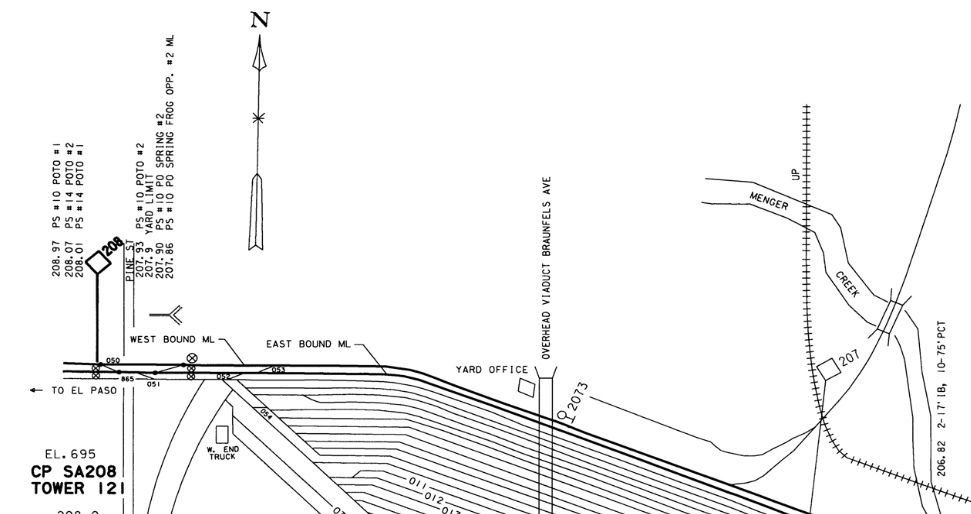

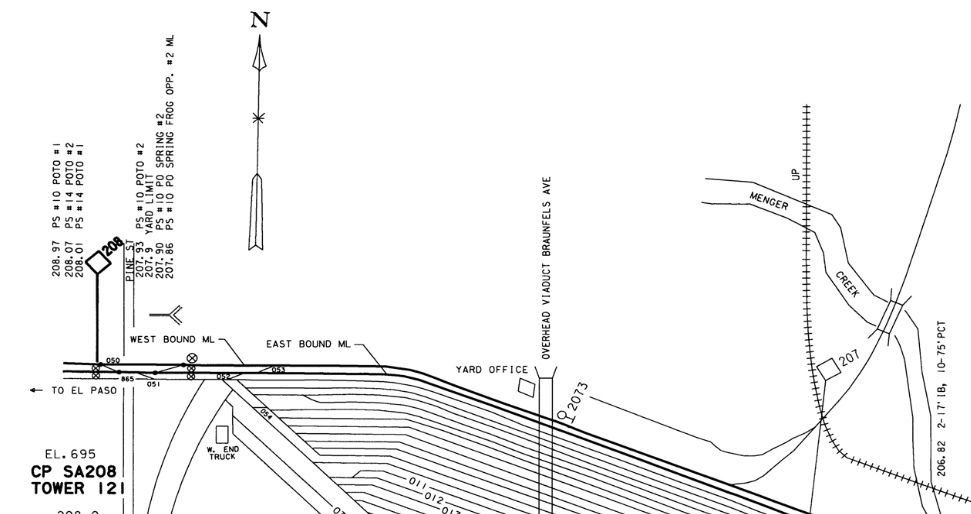

Below Left:

As shown by this map snippet from a 2008 study of San Antonio rail

freight by HNTB Corp. for the Texas Dept. of Transportation, the CP

SA208 control point remained associated with Tower 121 even though the

tower was long gone by then. The Union Pacific (UP) track that

comes in from the right and curves north was industrial trackage that no

longer existed in 2008. It was the remnant of the original Missouri,

Kansas & Texas (MKT, "Katy") line that came south from

Austin. When built, the Katy main line into

San Antonio had merged into East Yard and there was some limited ability

for the Katy to use the yard for its purposes. In later years, the Katy

bypassed East Yard as the main line was extended south to

Tower 112.

Below Right: undated photo of Tower 121 by Doug Woods

(from Southern Pacific's Eastern Lines 1946-1996

by David M. Bernstein, published by the North Texas Chapter, National Railway

Historical Society)

|

|

The Buffalo Bayou, Brazos and Colorado (BBB&C) Railway

was the first railroad in Texas, chartered several years before the Civil War.

The BBB&C began at Harrisburg on Buffalo Bayou

southeast of Houston and laid twenty miles of

track west to Stafford's Point in 1853. By 1855, twelve additional miles had

been built to Richmond, the county seat of Fort Bend County. By the time the

Civil War began in 1860, tracks had been laid 48 miles farther west to the tiny

community of Alleyton near the Colorado River. Instead of crossing the Colorado,

the BBB&C planned to remain east of it and follow the river north to La Grange and Austin. When economic conditions after the Civil

War left the BBB&C

unable to make payments on its construction contract, a court gave the

BBB&C's assets to the contractor, William Sledge.

Thomas Peirce had

done some legal work for the BBB&C, giving him insight and ideas for how to make

the BBB&C profitable. Peirce (with the unusual ei spelling of his last

name) was a wealthy Boston businessman, lawyer and landowner (including a large

sugar plantation near Arcola.) As

Sledge tried to make a go of it with the railroad he inherited, Peirce formed an

investor group in 1870 for the purpose of acquiring the railroad from Sledge.

Peirce and Sledge struck a deal, and the sale formally closed in 1874, by which

time

Peirce had rehabilitated the BBB&C. He had also petitioned the Legislature

to modify the BBB&C

charter to authorize building to San Antonio

instead of La Grange and Austin. As approved by the Legislature, the BBB&C's revised charter also allowed the railroad

to connect with any railroad to the Pacific (an innocuous provision

that proved to have a profound impact -- Peirce knew what he was doing.) The railroad's name

also was revised; it

would be the Galveston, Harrisburg and San Antonio (GH&SA) Railway.

Peirce resumed construction, heading west toward San Antonio and completing 71

miles to Luling by the end of 1874. Limited

construction was done in 1875 (15 miles) and 1876 (15 miles), with a final push

of 24 miles into San Antonio in 1877.

|

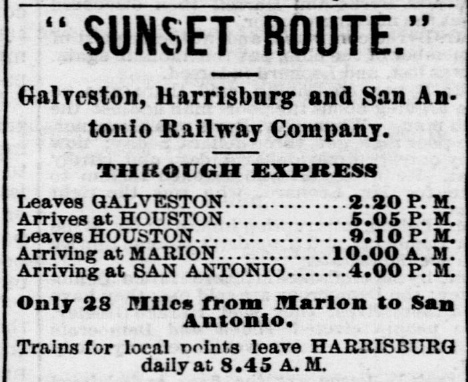

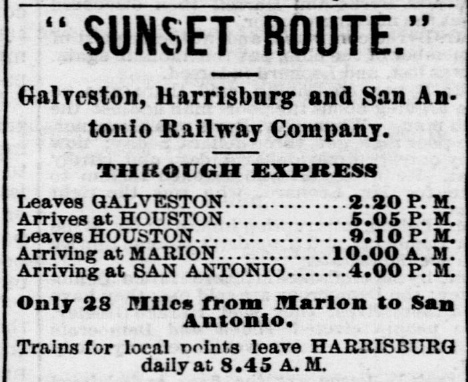

Left:

As Peirce built west in 1874, he claimed the marketing identity "Sunset

Route", which remains in common use today. This ad from the

Galveston Daily News of March

3, 1877 shows the GH&SA arrival into San Antonio at 4:00 pm after

a 10:00 am arrival at Marion. The odd note of "28 miles from Marion to

San Antonio" gives away the secret: the final segment was by stage

coach. Marion was a tiny settlement near the west bank of the Guadalupe

River that happened to be the end of track for the GH&SA for several

months in the fall of 1876 and the winter of 1877. In October, 1876,

newspapers reported that a contract by Peirce to build a branch line from Marion

to New Braunfels had been let, but no tracks were ever laid.

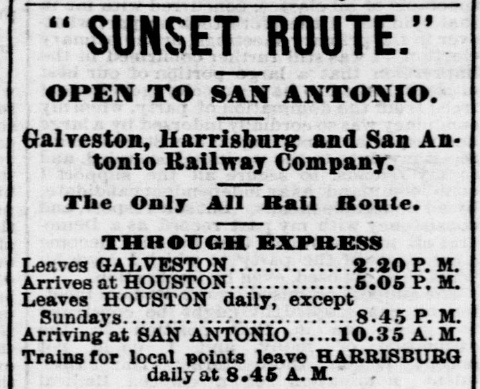

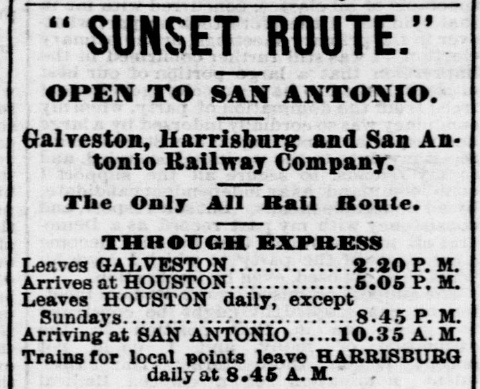

Right: The

following day, March 4, 1877, the ad in the

Galveston Daily News changed to

highlight "All Rail Route". Marion is no longer mentioned at all, and

the arrival into San Antonio was 10:35 am. The departure from Houston

was 25 minutes earlier at 8:45 pm. |

|

In the early 1870s, the dominant steamship line

operating in the Gulf of Mexico was owned by Charles Morgan. Morgan had

recognized the value of adding railroads to his industrial portfolio,

one of which was the Gulf, Western Texas & Pacific (GWT&P)

operating between Victoria and the port town of Indianola.

The

charter approval by the Legislature had required Morgan to build

additional tracks north of Victoria, so he extended the GWT&P from

Victoria to Cuero in 1873. As Peirce's line had begun to inch closer to

San Antonio, Morgan perceived a threat to his business. San Antonio was

the second largest city in Texas (after Galveston), and Peirce's line to

Houston would offer superior shipping options through Galveston, a

substantially larger port. Although Morgan

had major operations there, he did not own rail lines in the area. Since

tracks had not yet reached San Antonio, Morgan had his steamship line

avoid routing shipments to San Antonio via the various endpoints the

GH&SA (e.g. Marion), preferring

instead a route through Indianola on his GWT&P to Cuero, within 80 miles

of

San Antonio.

Right:

the Galveston Daily News,

January 3, 1877, quoting the San Antonio

Herald

The death of Charles Morgan in 1878 precipitated

the sale of his steamship line and railroads to Southern Pacific (SP) in

1883 as part of SP's grand plan for Texas and Louisiana. By then, Thomas

Peirce had already become an important component of the plan. |

|

Within a year of reaching San Antonio in 1877, Peirce and

SP Chairman Collis Huntington were discussing a potential

partnership. Given

Peirce's early 1870's request that the revision to the BBB&C charter include the right to

connect with any Pacific railroad, their discussions may have secretly

dated back much earlier. SP was building east from California to Yuma, Arizona. Huntington

had decided to continue beyond Yuma to El Paso, and

then onward to Houston and New Orleans. Peirce possessed what Huntington

desired: a Texas railroad charter that could be deemed to authorize construction

between San Antonio and El Paso to connect with SP at the New Mexico border --

SP certainly qualified as any Pacific railroad. The bonus was that

Peirce's GH&SA already covered 200 miles of the distance between El Paso and Houston. To accomplish

his plan, Huntington needed track construction between San Antonio and El Paso

to be performed under the GH&SA's charter, so he offered to finance the entire job

for Peirce. Both men understood that by loaning the funds, SP would hold

substantial GH&SA debt and be well-positioned to acquire it outright, yet Peirce

was agreeable. At age 60, he had already surpassed life expectancy for that era,

he couldn't run the GH&SA forever, and he could ensure its long term viability

by partnering with SP. Work began in

June, 1881 with construction forces building west from San Antonio and east from

El Paso. After a bit more than a year and a half, the construction crews met at

the Pecos River on January 12, 1883, where Huntington and Peirce drove a Silver

Spike signifying completion of a major portion of SP's southern transcontinental

rail line. SP leased the GH&SA for several years and ultimately acquired it.

Less than three years after the Silver Spike ceremony, Peirce died at age 67.

|

Left:

map of San Antonio rail lines showing the five interlocking towers that

have been commissioned in San Antonio.

Tower 2 was authorized for operation by the

Railroad Commission of Texas (RCT) on October 9, 1902 with a 10-function

mechanical interlocker. It controlled the grade crossing of the San

Antonio & Aransas Pass (SA&AP) with the GH&SA in south San Antonio. The

SA&AP line went south to Corpus Christi and

north to Kerrville.

It took nearly fourteen years for a second

interlocking tower to be commissioned in San Antonio.

Tower 105 commenced operations on April 29,

1916 at the GH&SA's crossing with the International & Great Northern

(I&GN). The crossing had existed since 1881 when the I&GN built through

San Antonio on its way to Laredo.

In 1912, the San Antonio Belt &

Terminal (SAB&T) Railway was chartered by investors associated with the

Missouri, Kansas & Texas (MK&T, "Katy") Railway to build terminal

facilities and switching tracks around San Antonio. Construction finally

began in 1916 and the SAB&T began operating in 1917 under a long term

lease to the Katy. On October 28, 1918, Tower

109 was commissioned at the crossing of the SAB&T and the SA&AP

south of downtown.

The SAB&T construction had crossed the GH&SA

at an acute angle about a half mile east of Tower 2. This location was

interlocked as Tower 112 on December 30,

1919. About 2.5 miles farther east, the SAB&T curved north and

proceeded through the east side of San Antonio to connect to the Katy's line to

New Braunfels, San Marcos, Smithville and

Houston, with access to

Austin and points north via the I&GN from

San Marcos.

The GH&SA opened a freight yard northeast of downtown

San Antonio known as East Yard. The timeframe in which it was built has

not been determined, but it is present on the 1904 Sanborn Fire

Insurance map of San Antonio (and it may have existed well before then;

Sanborn Maps prior to 1904 don't cover that area of northeast San

Antonio.) Tower 121 was commissioned by RCT on April 10, 1925 with a

26-function electrical interlocker. It was strictly for SP's use in

managing access to East Yard.

|

In 1893, the San Antonio & Gulf Shore was chartered

to build from San Antonio to the Port of Velasco near Angleton. With only 29 miles of track

laid out of San Antonio, it was sold in foreclosure in 1897 to the newly

chartered San Antonio & Gulf (SA&G). In 1905, the SA&G was acquired by

SP and merged into the GH&SA under a charter amendment requiring the line to be

extended southeast to Cuero from its current end-of-track at Stockdale. Under

the GH&SA charter, SP built 17 miles from Stockdale to Smiley in 1906, and the

remaining 27 miles to Cuero in 1907. The tracks to Cuero from San Antonio

departed the GH&SA main line about 2.5 miles east of East Yard, a location known

then as

Gulf Junction (presumably named by SA&G because it led to the GWT&P at Cuero.) Today, the connection is known

as Salado Junction, but the tracks extend only two miles southeast

to serve industry spurs. The tracks beyond San Antonio were abandoned to

Stockdale in 1959 and to Cuero in 1971.

Tower 121 housed an interlocking

plant at East

Yard for SP's use; it was

not a typical tower at a junction of two or more railroads.

Arguably, state law did not grant RCT jurisdiction over the tower because there was only one railroad involved;

state law authorized RCT to manage crossings of two or

more railroads.

A similar issue had been presented in 1924 with the eventual commissioning of

the yard tower

at New South Yard in Houston. The Houston Belt & Terminal (HB&T) Railroad built New

South Yard and its yard tower at the same time (c.1910) it was building Houston

Union Station and an interlocking tower to control station ingress and egress. HB&T did not request RCT approval for

either

tower under the assumption that the law gave them an exemption from doing so,

i.e. HB&T owned all of the tracks at Union Station and New South Yard so there were no other

railroads involved.

More than a decade

later, an expansion of the Union Station tower coupled with policy changes at RCT

led to the decision by HB&T to seek formal RCT authorization (whether there was

any coercion to do so is undetermined.) The interlocker at Union Station was

commissioned as Tower 116 by RCT, and the one at

New South Yard was commissioned as Tower 117 on the same day,

March 14, 1924. This clearly set a precedent for yard

towers that undoubtedly affected Tower 121 as well as RCT's later decision to require Santa Fe to seek approval for their yard

interlocker at Canyon. The RCT

interlocker archives held by DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University,

have a letter to RCT from Southern

Pacific dated April 8, 1925 requesting interlocker design

approval and a tower number assignment for their East Yard tower. The letter states "This plant does not

serve railroad crossings at grade but is being constructed for our convenience

and improvement in operation." Approval for Tower 121 was granted

two days later without inspection. SP clearly

understood that RCT had established a precedent for yard towers with Tower 117.

Above Left: The 1951

update to the 1912 Sanborn Fire Insurance map of San Antonio shows Tower 121 as

a 3-story structure adjacent to SP's tracks at East Yard. The meaning of the

annotation below "R R Tower" has not been determined. The map shows

the major part of the

staircase located behind the building. Photos show a landing with a door on the

second floor on the west side of the building, and a landing and a door on the

third floor on the east side of the building. The third floor landing on the

east side appears to be depicted on the map whereas the second floor landing is

not shown on the west side. Perhaps it was added after 1951. On the 1951 map,

the building behind the tower is elsewhere labeled "Sears".

Above Center: This aerial

image ((c)historicaerials.com) was taken in 1966 showing the roof of Tower 121

as a small, light-colored square (yellow arrow.) The adjacent street west

of the tower is Olive, and in those days, it went over the tracks on a bridge

(pink arrow). Above Right:

This 2023 image from Google Earth shows that both the tower and the bridge

over the tracks have been removed. Below:

These four undated photos of Tower 121 were

taken by Carl Codney (left) and Myron Malone (the other three.)

All were taken prior to the installation of the control point signs visible in

Art Fisher's 2002 photos.

Stuart Schroeder provides his recollection of working

at Tower 121 in the early 1980s.

My experience working at Tower 121

for Southern Pacific in San Antonio began on April 26, 1982 when I was “bumped”

off my job at SP RTC (Rail Traffic Control, formerly

Tower 87) in Houston. I learned quickly that there were no other jobs I

could hold with my seniority on my entire clerical seniority district. Southern

Pacific had four clerical seniority districts on the Texas & Louisiana Lines

during the 1980s. District I covered jobs in the Houston headquarters building

on Franklin St. District II covered clerical jobs on the Lafayette Division.

District III was my district. It covered jobs primarily on the Houston Division

and including the former Houston & Texas Central line between Houston and

Denison. District IV covered the San Antonio

Division including the El Paso terminal to

Rosenberg (Sunset Route) and the former

Victoria Division including the

Rio Grande Valley.

My seniority was only good in

District III. However, if a clerical job went “no bid” in another district it

was bulletined in the other seniority districts before a new employee was hired.

Fortunately, there were three “no-bid” guaranteed extra board jobs from East

Yard on the bid list at that time. I drove to San Antonio and talked with the

clerical supervisor at East Yard about the jobs. I also informed him that I was

a qualified interlocking tower operator. The supervisor was quite pleased when I

mentioned that and he told me that he had a challenging time getting people to

work in the towers. I told him that I would submit bids on all three positions.

I personally turned in my bids at the superintendent’s office and waited to see

if I would be awarded one of the jobs. I was assigned to one of the jobs and

began training at Tower 121 on May 4, 1982. I was force assigned to a temporary

vacancy on third trick at Tower 121 on May 21, 1982. I worked this shift until

June 25, 1982 when I was relieved by the regular assigned employee. I

immediately began training at Tower 112 until I qualified on July 16, 1982.

Following that, I occasionally worked both towers from the extra board while

learning various clerical jobs at East Yard.

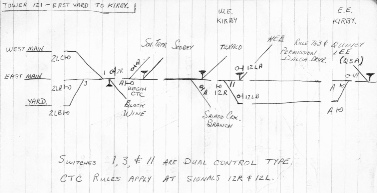

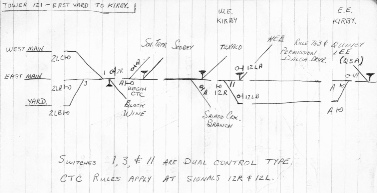

Tower 121 was interesting to

me in that it consisted of main track railroading, yard engine movements and

roundhouse moves from the diesel shop located on Hackberry Street. Three

distinct and separate machines were used to control traffic movements. The

original pistol-grip lever plant controlled the main track from just west of

Hackberry Street to the west end of East Yard. A home-built (in the SP signal

shop) push button CTC machine controlled the interlocking at the east end of

East Yard as well as the CTC between East Yard and the west end of Kirby. A

third push button machine controlled the interlocking and power switches into

the diesel shop. The hostlers frequently made “roundhouse moves” between the

various tracks in the shop often needing the main track for headroom. The

most fascinating part of working at Tower 121 were the manual crossing gates at

Hackberry Street and Pine Street controlled from a small box on the operator’s

desk with toggle switches. There were several annunciators that warned the

operator when to lower the gates in sufficient time to protect the crossing from

an approaching train. This was the most challenging part of the job. I wanted to

ensure that the motorists were protected from rail movements.

In early

1984 I was the successful applicant for the second trick position at Tower 121

and worked this shift until November 15, 1984. Following this, I worked at both

Tower 121 and Tower 112 from the extra board until I began training as a train

dispatcher in the San Antonio office on January 30, 1985.

Stuart recalls the former Katy track that had

originally connected into East Yard...

The MKT connecting track was still

partially in place when I first began working at East Yard in 1982. I seem to

recall that it was no longer connected to the SP. It had been out of service for

a number of years prior to my arrival at East Yard. The track that remained was

overgrown with brush. I'm not sure if it was still connected to the MKT down the

hill or not. That's all that I can remember. Interchange between SP and MKT

occurred at Yoakum Bend yard at the beginning of the Kerrville Branch near Tower

112. In fact, some of the tracks at Yoakum Bend were owned by MKT and the

remainder were SP. I recall that the track nearest the San Antonio River was

called the "river track". That track was owned by the MKT and I remember that

the Sloan yard engine worked the industry located there. I cannot remember what

the industry was, however.

Stuart provides these Tower 121

sketches that he made during his time in San Antonio. (click to enlarge)

Tower 121 officially closed on February 26, 2001 at 9:00 am. At that time,

the tower's control functions

were shifted to the Union Pacific (UP) Dispatching Center in Spring,

Texas; UP had acquired and merged SP in 1996. Beginning around December 20, 2002, the building began to suffer

severe damage from vandals. Corrugated siding was removed from

the tower and two fires of suspicious origin were set but did not burn it to the ground. On the night of January 16, 2003, the tower burned to the ground

from a fire probably set by vandals. The next day, a contractor

for UP removed the charred remains. The lever controls for the tower were

reported to have been preserved by a San Antonio

historical group well prior to the fire.

Last Revised: 2/29/2024 JGK - Contact the Texas

Interlocking Towers website