Texas Railroad History - Tower 85 (Baker Street) and

Tower 189 - Houston (Magnolia Jct.)

Two Crossings of the Houston Belt &

Terminal Railway South of Downtown Houston

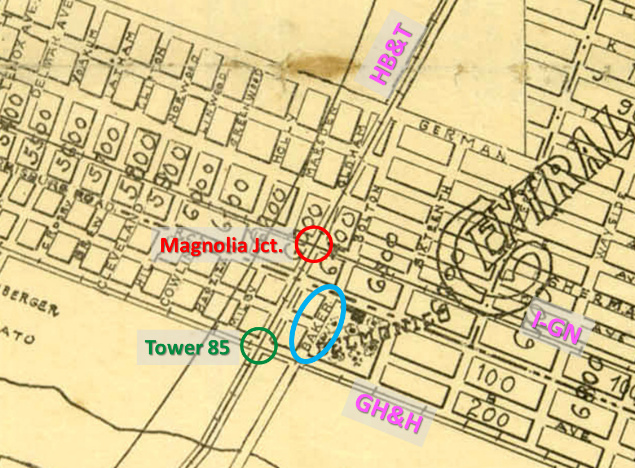

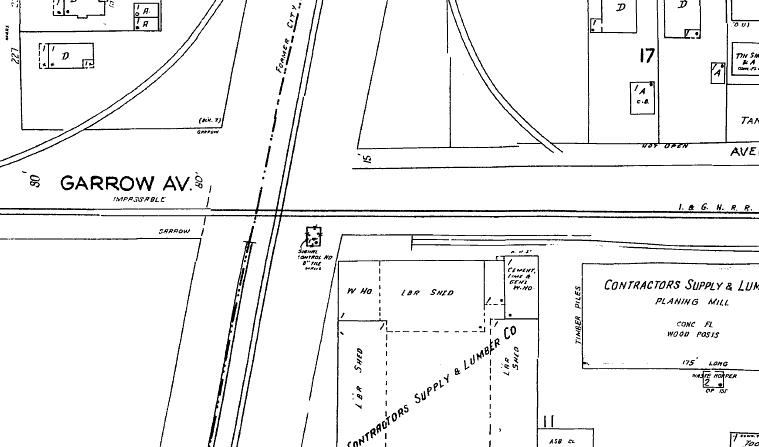

Above Left: Kenneth Anthony

took this photo of the Tower 85 crossing in 1986. The view is south along the

East Belt portion of the Houston Belt & Terminal (HB&T) Railway. Long before

the East Belt materialized, the crossing track was built by one of the early railroads in Texas,

the Galveston, Houston & Henderson

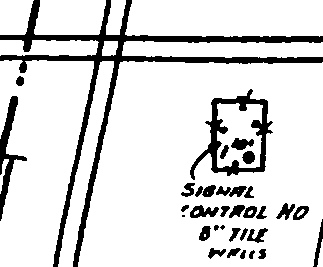

(GH&H) Railway. Above Right: The

reason the Railroad Commission of Texas began to list the location of Tower 85

(green circle) as "Houston (Baker St.)" in 1927 was to distinguish it

among all of the

towers generically assigned as "Houston". Tower 85 got the Baker Street

postscript because that was the closest street (blue oval) to the tower, as

illustrated by this annotated image from a 1913 Houston street map (courtesy,

Texas State Library & Archives.) Later, Baker St. was renamed 65th St.

and it no longer crosses the tracks (if it ever did - maps of this nature were

often prospective based on a town's plat.) Nearby Magnolia Junction (red circle)

was another crossing of the East Belt, where it intersected a branch line of the

International & Great Northern (I&GN) Railroad.

Tower 85 has controlled a major rail junction in

Houston for more than a century, a crossing of the

Houston Belt & Terminal (HB&T) Railway and the Galveston, Houston & Henderson

(GH&H) Railroad southeast of downtown. The GH&H was one

of the first railroads in Texas, chartered in 1853 to build between Houston and

Galveston, with plans to build north to Henderson in deep east Texas.

Construction was delayed but eventually began at

Virginia Point on the mainland; rails reached

Houston in 1859 (and never went further.) The two-mile long trestle from

Virginia Point onto Galveston Island was completed the following year, just in

time to be used by both sides during the Civil War. For a variety of reasons --

most especially yellow fever quarantines against Galveston Island -- freight

into Houston bound for

Galveston on the GH&H did not always reach the

Island. Sometimes it was off-loaded at Houston

and shipped by barge down Buffalo Bayou to Galveston Bay to be loaded directly

onto ships, bypassing the Galveston wharves. To be fair, Houston shippers were

trying to overcome restrictive policies practiced by the Galveston Wharf Company

that favored Galveston's shippers over Houston's.

As S. G. Reed explained

in his reference tome A History of the Texas Railroads

(St. Clair Publishing, 1941) Galveston's citizens were certain that Houston

was...

...inspired less by fear of the

plague than by a desire to hamper Galveston trade, as the quarantines were

established with regularity every fall when cotton was moving and trade was

best.

After a post-war foreclosure and restructuring, the GH&H

was acquired by rail baron Jay Gould in 1882 who quickly sold it to the

Missouri, Kansas & Texas (MK&T, "Katy") Railway of which he

was President. Since the Katy had no tracks near

Houston or Galveston at the time, Gould directed the Katy to lease the GH&H to the International & Great Northern (I&GN) Railroad, another company

he controlled. In 1888, Gould was fired by Katy stockholders, and five years

later, tracks of the newly independent Katy railroad reached

Houston. The Katy filed a lawsuit to revoke the lease

of the GH&H to

the I&GN. In a final settlement reached in 1895, the Katy sold a half interest

in the GH&H to the I&GN, with each having permanent, unlimited rights to use the GH&H

tracks.

When the I&GN came out of bankruptcy in 1922 free and clear of the Gould

family (and with a new name, the International - Great Northern,

"I-GN") it was soon acquired by Missouri Pacific (MP) and

became fully

merged into MP in 1956. In 1982, MP was acquired by Union Pacific

(UP) but continued to operate under the MP name. Six years later, UP

acquired the Katy and merged it into MP the following year. The GH&H was merged

at the same time because MP now owned all of it: the 50% share inherited from

the Katy and the 50% share it had acquired from the I-GN acquisition in 1925.

The other railroad at Tower 85 was the HB&T, formed in

1905 by four railroads to provide switching services around Houston, including

building tracks to facilitate interchange and erecting a union passenger station downtown. The

four railroads -- the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe

(GC&SF) Railway, the Trinity & Brazos Valley (T&BV) Railway,

the Beaumont, Sour Lake & Western Railway, and the St. Louis,

Brownsville & Mexico Railway -- each had a

quarter interest in the HB&T, and each contributed other assets, mostly trackage.

Although Santa Fe's main line

out of

Galveston (to Temple) had avoided a route through Houston

due to the aforementioned service disruptions, by

1883, the Houston economy had become so important that Santa Fe could no longer ignore

it. They built a 26-mile branch that year from their main line at Alvin into downtown

Houston. They also built a yard (eventually known as South Yard) along

this branch approximately two miles south of downtown. About 25 years later,

access to

HB&T's East Belt began near the south end of this yard. HB&T took over

yard operations from Santa Fe and then built New South Yard (Tower

117) directly south of the East Belt connection.

Railroad

Commission of Texas (RCT) records attribute two construction activities to

the HB&T: 8.13 miles in 1907 and 9.74 miles in 1912. This construction produced a

semi-circular belt line around the east side of Houston along with new tracks

north and south out of downtown. While RCT construction records do not provide

dates for specific track segments, RCT's interlocker records show that

Tower 76 was commissioned in 1908. This was a

crossing of the Houston East & West Texas (HE&WT) Railway and the

HB&T on the north side of Houston, implying that HB&T's 1907 construction

included the northern part of the belt line. The HB&T made

a direct connection into the T&BV which was building into Houston on the

northwest side of town in 1907. Nearing

Houston, the T&BV tracks curved due east, becoming HB&T tracks at some point

near (and west of) Tower 80. This completed the T&BV's

Dallas - Houston main line; it became an important link for overhead traffic but

it lacked the local

traffic necessary to become profitable. The T&BV commenced a long

receivership in 1914 that ended in 1930 when its assets were transferred to the newly organized

Burlington-Rock Island (B-RI) Railroad, a joint venture of the

Chicago, Burlington & Quincy (through its Ft. Worth & Denver

City subsidiary) and the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific railroads.

|

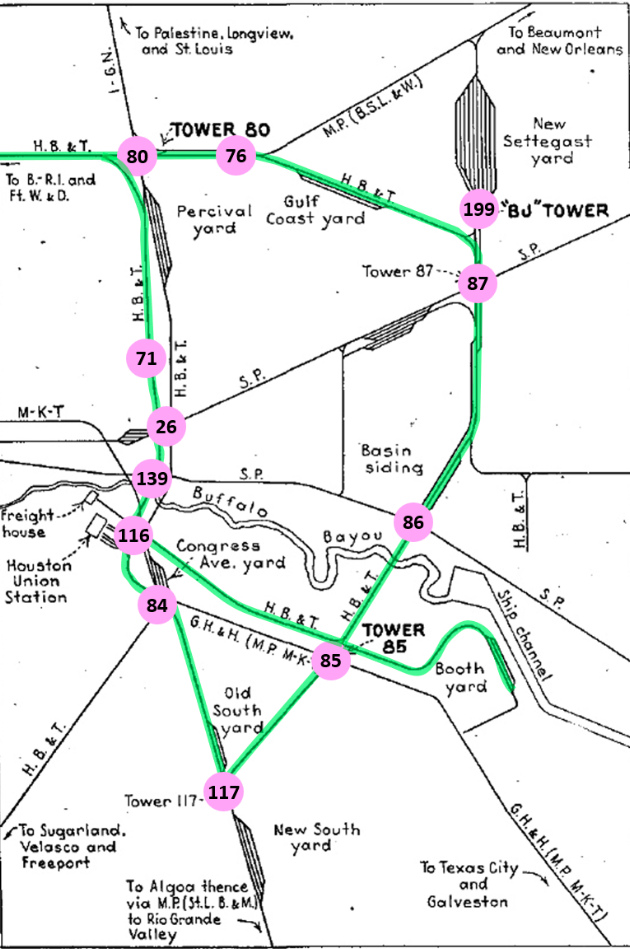

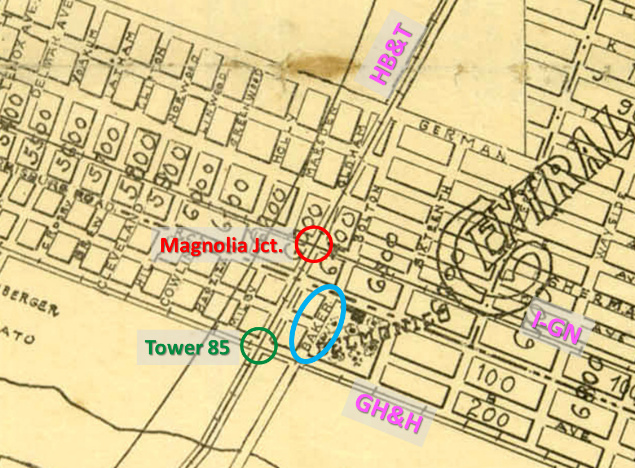

Left:

This map appeared in the March, 1952 edition of

Railway Signaling and Communications

in an article discussing recent interlocking changes in Houston. It has

been annotated to illustrate the belt line constructed by

the HB&T around the east side of Houston. Note that the published map

omitted some rail lines, e.g. the tracks of the HE&WT,

which crossed the HB&T at Towers 71 and 76.

Several towers

have been annotated that were omitted on the original map.

The following railroad abbreviations are used on the map:

B. - R. I. (Burlington - Rock Island)

B. S. L. &

W. (Beaumont, Sour Lake & Western)

Ft. W. &

D. (Fort Worth & Denver)

G. H. & H.

(Galveston, Houston & Henderson)

H. B. & T.

(Houston Belt & Terminal)

I - G. N.

(International - Great Northern)

M - K - T

(Missouri - Kansas - Texas)

M. P. (Missouri

Pacific)

S. P. (Southern Pacific)

St. L. B. & M. (St. Louis, Brownsville &

Mexico)

Below:

Tower 189 (Magnolia Jct.) isn't marked on the map at left; it is

located

at the top of the Tower 85 circle, a crossing of two HB&T lines. This

was originally the I-GN Magnolia

Branch, the rails being fully intact in 1952 but since abandoned from

Magnolia Jct. to downtown. As for the

Houston Electric streetcar line that formerly occupied Harrisburg Blvd., Houston's light rail METRORail Green Line now uses the right-of-way. The final step in opening

the Green Line was completion of a bridge over HB&T's East Belt. In the image

below, METRORail's shops and storage tracks can be seen above the light blue "GH&H" label.

(Google Earth image)

|

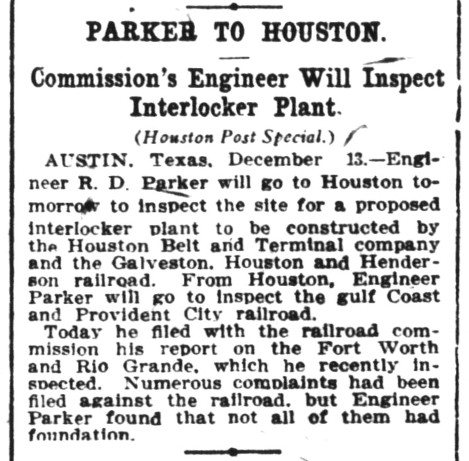

Documents in the RCT archives at DeGolyer

Library, Southern Methodist University, include a December 8, 1910

letter from HB&T to RCT submitting the Tower 85 proposal to protect "...the East Belt Line tracks of this company and the tracks of the

GH&H railroad at Baker Street, Houston." RCT engineer R. D. Parker had

serious concerns. He penned a memo four days later questioning whether the plan should be approved. His main issue was that the design

didn't account for the proximity of two additional HB&T crossings -- an

electric interurban and the I&GN's Magnolia Branch -- that were near the

GH&H crossing (see satellite image above.) Parker wrote ... "There is another steam

line that should be taken into the plant I think and an interurban line as

well."

Right:

In response to Parker's concerns, RCT dispatched him to visit the site, as reported in the

Houston Post of December 14, 1910.

[As a side note, Parker was then scheduled to inspect the Gulf Coast and

Provident City Railroad, a line planned for a town being built 26 miles southeast of Hallettsville in

southern Colorado County. Rail historian S. G. Reed reports the railroad's charter was granted on January 11, 1910.

Eleven months later, there would not be much

for Parker to inspect. The railroad never proceeded beyond some grading efforts, and Provident

City peaked at 500 people and then dissolved into ghost town status.]

Parker eventually signed off on the proposal. Notes

suggest that

the inclusion of spare levers for future

use in the interlocking plant was sufficient to overcome his objections.

Tower 85 was commissioned by RCT on May 3, 1911 with a 12-function

mechanical plant. RCT's list of interlockers dated December 31, 1923

reduced the number of functions to 11, and, suspiciously, changed the

commissioning date to May 3, 1919. This error was corrected three years

later; the number of interlocker functions increased to 19 and the date

reverted to 1911. This was merely a swap of the 2-digit year and the

number of interlocker functions, i.e. the original error was just a

typesetting mistake. RCT's list dated December 31, 1927 inexplicably

changed the commissioning date to February 10, 1911. A year later, the

number of functions increased to 21 and the commissioning date reverted

to May 3, 1911. |

|

An expert on Houston's electric lines, Steve Baron, explains that Parker was

slightly mistaken...

"The electric line on Harrisburg Road was a

streetcar line, not an interurban. The steam road people may have referred to it

as an interurban but it was just a long suburban streetcar line, built and

operated by the Houston Electric Co. which was the local streetcar

operator. This track was used by two routes, the Harrisburg line and the Central

Park (later called Port Houston) line. Service on the Harrisburg line ended in

1928 and on the Port Houston line in 1936, at which point the crossing was most

likely removed. As was the case with virtually all crossings between city

streetcars and steam roads, the crossing was uncontrolled and the railroad

trains had priority."

As the annotated satellite image above shows, Parker's concerns were well-founded. The

diamond at Tower 85 was only about 700 ft. from the streetcar crossing at

Harrisburg Blvd, and the I&GN's Magnolia Branch was approximately 300 ft. beyond. All trains stopped at

the uncontrolled Magnolia Branch diamond; this was the law for uncontrolled

crossings of two railroads at grade and it was also explicitly stated on a 1934

drawing of the Tower 85 interlocking plant. Although Tower 85 benefitted GH&H

trains by allowing them to maintain track speed if the diamond was unoccupied, HB&T trains passing through

Tower 85 were either slowing down (northbound) for the stop at Magnolia

Jct., or attempting to gain speed (southbound) from having stopped there already.

Tower 85 would never maximize operational benefits for HB&T until the Magnolia

Jct. diamond was interlocked. RCT held a hearing on October 30, 1942 to approve

an automatic interlocker for the Magnolia Jct. crossing and the plant was commissioned as Tower 189 shortly thereafter.

|

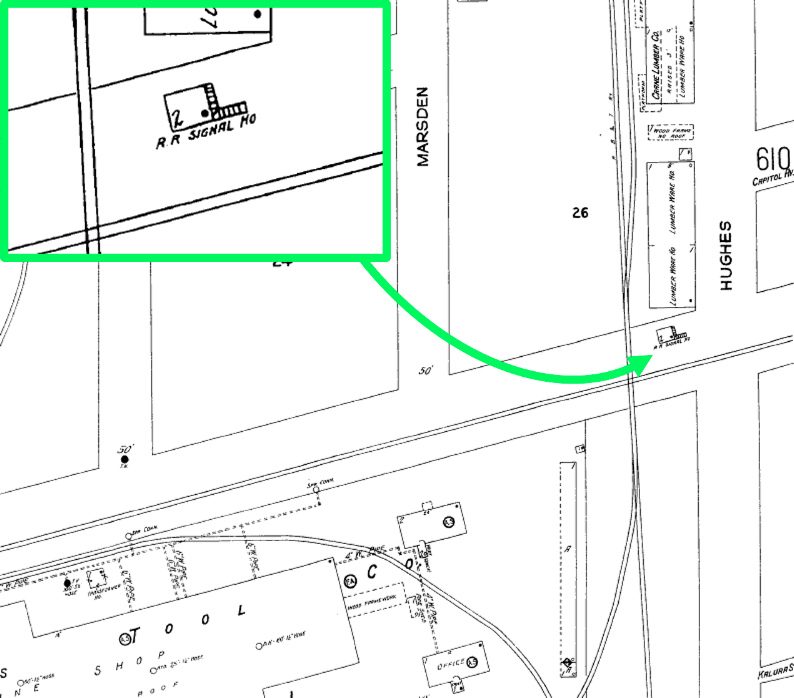

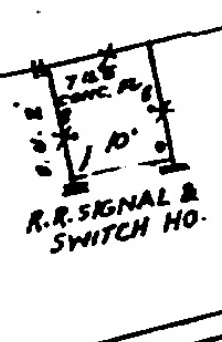

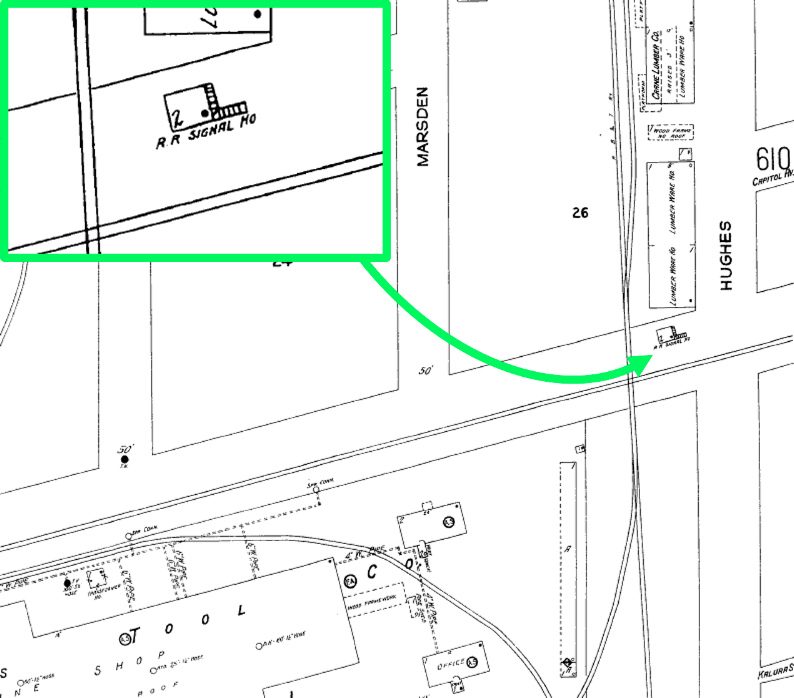

Left: The 1925 Sanborn Fire Insurance map of

Houston shows the precise location of Tower 85 in the northeast quadrant

of the diamond west of Hughes St. Magnification (inset at upper left)

identifies it as a two-story "R R Signal Ho" (railroad signal house) with an external staircase on the

east side that incorporated a right angle turn. The landing at the top

level was at the opposite end from the door (black dot.)

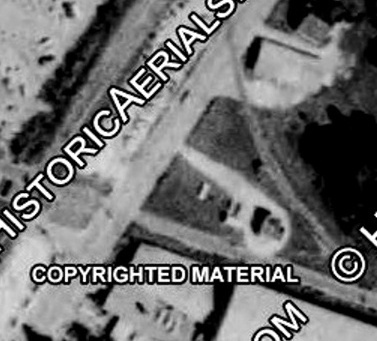

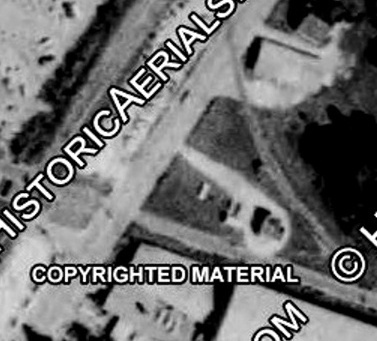

Above: ((c) historicaerials.com)

The dark black square in the middle of this 1930 image is the roof and

shadow of Tower 85. The tower is in the northeast quadrant of the

diamond, roughly equidistant between the HB&T tracks (to the west) and

the Hughes St. roadway (to the east.)

Below: ((c) historicaerials.com) The tower is

not present in this 1947 image, replaced by what appears to be a

trackside equipment cabinet.

|

RCT initially listed Tower 85's location simply as "Houston", but beginning

with the 1928 RCT Annual Report issued in January of that year, the site was

renamed Houston (Baker St.) Files at DeGolyer Library contain RCT correspondence

dated March 16, 1934 authorizing the Tower 85 interlocker to be remotely

controlled from Tower 86. This presumably led to the demise of the Tower 85

structure and likely explains why no photos of it have been located. However, there is documented evidence (below) that some sort of Tower 85 structure was reestablished

in later years.

|

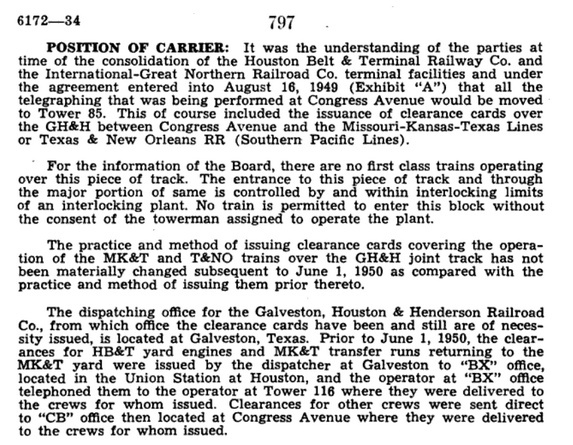

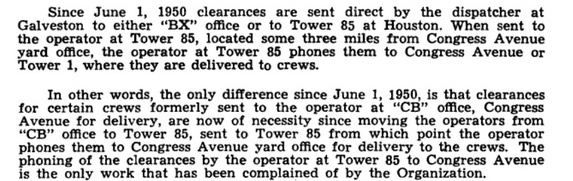

Left and Above:

A case published in 1953 from the National Railroad Adjustment Board

involved a union complaint about loss of telegraph operator jobs due to

a terminal consolidation agreement between the I-GN and HB&T. The

agreement specified that "telegraphing that was being performed at Congress

Avenue would be moved to Tower 85." Clearly,

some kind of manned Tower 85 structure

existed when the agreement was made in 1949. The passage states that

Tower 85 was "three miles from Congress Ave. yard office" which is

reasonably close to the actual distance, i.e. presumably this new Tower 85

was at the traditional Tower 85 junction. Was there a reason that

operations personnel needed to be at this specific location? Or...was it merely convenient real estate

owned by HB&T, i.e. a place to put a building (or use an existing

one) that could just as easily have been

located somewhere else? The answer has not been determined.

The

passage above also has a mysterious reference to "Tower

1", apparently some sort of Houston-area control point, not the

Tower 1 located in Bowie, Texas. |

|

|

|

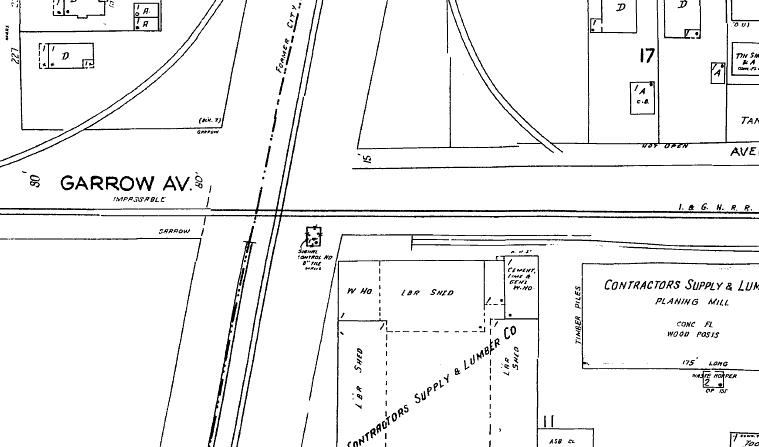

Far Left: The March, 1950 update to the Sanborn Fire Insurance

maps of Houston shows a one-story "Railroad Signal & Switch House"

located in the northeast quadrant of the Tower 85 crossing. This

concrete ("Conc.") structure was east of Hughes St. whereas the original

tower was west of Hughes St.

Middle: ((c) historicaerials.com)

This 1966 aerial photo of the Tower 85 crossing shows a building in the

northeast quadrant consistent with the structure shown on the Sanborn

map. A light gravel parking area surrounds the building and connects to

Hughes St.

Near Left: A Tower 85 equipment cabinet remains intact

east of Hughes St.

as of December, 2019. (Google Street View.) |

Tower 85 Site Photos by Tom Kline (click to enlarge)

Magnolia Junction

(Tower 189)

In 1890, John T. Brady established the

Magnolia Park community on 1,374 acres he owned

east of Houston along the south bank of Buffalo Bayou. He promptly built a large amusement area

on the waterfront, and to ferry passengers there from downtown Houston, Brady chartered the Houston Belt & Magnolia Park (HB&MP) Railway.

He also planned to develop industries along his waterfront, to be served by his

railroad. The HB&MP lasted only a year before

entering receivership, but it managed to stay afloat during the 1890s by leasing

some of its tracks to other railroads. The HB&MP was sold to Herbert F. Fuller

in November, 1898, and six months later, Fuller transferred the property to the

newly chartered Houston, Oak Lawn & Magnolia Park (HOL&MP) Railway. Shortly

thereafter, the HOL&MP was sold to the I&GN. Plans for the Houston Ship Channel

were in work and the I&GN had the same vision that motivated Brady to charter the

HB∓ ocean-going ships would soon traverse Buffalo Bayou and industries would

populate the waterfront. The City of Houston owned some of this land and

established the Port of Houston, served by the I&GN. When HB&T's East Belt was

constructed, it crossed the I&GN Magnolia Branch a thousand feet north of the

Tower 85 crossing. Aerial imagery from 1930 shows a connecting track had been

added in the northwest quadrant, and the crossing was interlocked in 1942 as Tower

189. At some point after 1950, ownership of the branch was

conveyed to the HB&T.

|

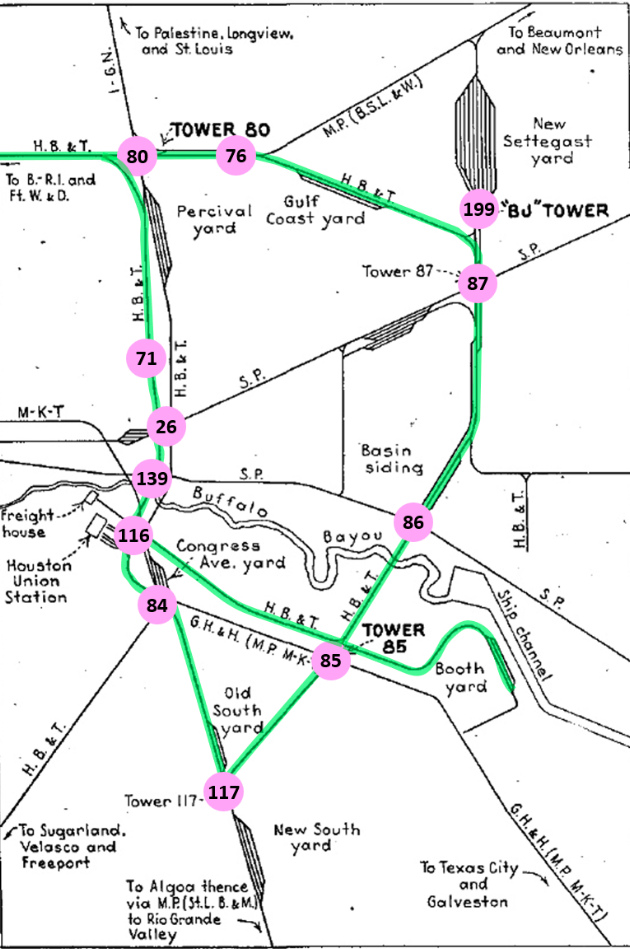

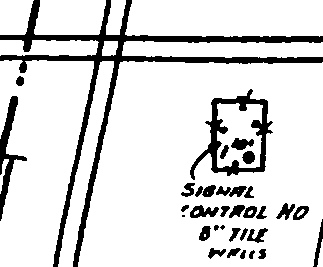

Left:

The 1950 update to the 1925 Sanborn map shows an equipment cabinet

located at Magnolia Junction.

Below: Magnification

reveals a one-story "Signal Control House" with 8-inch tile walls,

presumably an equipment cabin that housed the automatic interlocker. A

door on the south side provided access for maintenance personnel.

|

Above Left: This view is to the west-northwest

toward Magnolia Junction from 65th St. Whereas the tracks originally continued

straight ahead into downtown, sometime prior to 1984, the Magnolia

Branch

tracks west of the East Belt were abandoned. (Google Street View, 2017)

Above Right: Kenneth Anthony

explains this 1991 photo he took looking west on Avenue C, the street where he

lived as a kid:

"In the 1950s into the 1990s, SW diesel switchers were seen on

nearly all HB&T jobs. All were black when I was kid, then black with yellow

tiger safety stripes on the corners, and finally yellow. This HBT switcher is

going south on the East Belt line, with the Magnolia Junction northeast quadrant

curve in the foreground." The northeast quadrant curve

that Kenneth references is the right-hand track in the image above left.

Kenneth Anthony grew up in a house located on the

southwest corner of Avenue C and 65th St., literally a stone's throw from Magnolia

Junction. Below are some of Kenneth's recollections of Magnolia Junction and the

trains that passed through it:

A little about Magnolia Junction in

Houston, where I grew up. In the baby book my mom kept for me, she recorded that

the 9th word I spoke was "choo choo." My childhood bedroom had a window about

100 feet from the former Houston Belt & Magnolia Park Railway, a branch line of

the Houston Belt & Terminal, and 500 feet from the East Belt of the Houston Belt

& Terminal. ... I didn't know it as an infant, but there was a connection on the

northwest quadrant of the crossing of the East Belt and the Magnolia Branch. No

connections existed then on the other quadrants. There were major railroad

changes “in my backyard” when I was three years old, about 1947. The railroad

bought and tore down two houses at the west end of Avenue C, to clear

right-of-way to build a curve to connect the East Belt and the Magnolia line on

the north-EAST quadrant of the crossing. This formed a wye which allowed turning

locomotives or short cuts of cars. It also allowed continuous running between

the north end of East Belt with either west or east on the Magnolia Branch.

Whenever a train went around curve nearest my house, the wheels went

SKREEEEEEEE! ...

An incident

from before I started taking pictures of railroads. It was between 1953

and 1956 because those were the years I walked home afternoons from Burnet

Elementary School on Canal Street. A train derailed at Sherman Street,

right at the turnout where the northeast interchange curve from Magnolia Branch

connects to HB&T East Belt. A boxcar overturned and went through the side

of a house. I saw the aftermath. The house, south side of Sherman

and just east of HB&T East Belt was torn down and the property remains vacant

to this day.

I never saw any passenger trains as such on

the Magnolia Branch or the East Belt of the HB&T, but I

clearly remember one unusual sighting from my back driveway when I was three

years old, just after the new curve was laid on the back side of the block where

I lived. The squeal of a train around the curve got my attention in time to see

a flat car with seats mounted on it for people to ride. There weren’t any

riders, but it was so unusual I remembered it clearly. Never saw it again until

FIFTY YEARS LATER when I found archived copies of a Port of Houston promotional

magazine, and there was a photo of that car. The issue was dated May 1948, the

year I was 3 years old. An article said there had been an inspection train for

officials to view new railroad facilities at the port. The observation flatcar

may have been on a “shakedown cruise” or “dry run” before the bigwigs took their

tour when I saw it crossing 65th Street. The new curve built at Magnolia

Junction may have been one of the new railroad facilities to serve the port. It

was some two miles from the port, but it certainly made the south side of the

port more accessible to traffic on the HB&T.

As for everyday trains: I regularly

saw 2 or 3 short trains a day on the Magnolia Branch. Just about the time of the

curve construction, the locomotives changed from steam (“choo choo”) to diesel.

My dad described the diesels as going “boogedy boogedy boogedy” instead of “choo

choo.” Black switchers with white lettering, what I now know as Roman font,

pulling five or ten cars. And never a caboose on the Belt. As I grew a little

older and began looking farther, I saw quite a bit more traffic going up and

down the East Belt. Usually Belt switchers with a few cars. But sometimes

Missouri Pacific trains with blue F-units and blue GEEPs.

I was not sure

from childhood memory when the southeast curve was laid at Magnolia Junction,

but I found a photo and document which showed it had been done by 1953. The new curve

connected with the east track of the East Belt just short of Harrisburg

Boulevard and allowed direct runs of trains from the south on the East Belt

(such as from New South Yard) to the south side of the Port of Houston. Because

the crossing is not at right angles but at 72 degrees, the northeast curves and

southeast curves are not the same length, though apparently both are of about

the same radius (sharp!) The southeast curve only has to turn 72 degrees and can

do it in less distance from the crossing, than the northeast curve which has to

navigate 108 degrees of curvature, which puts its east end switch frog right in

the east edge of 65th Street. Laying the southeast curve required taking land

from the Contractor’s Supply lumberyard. The older lumber sheds at the west end

of the site, open to a central courtyard, were torn down and replaced with

fully-enclosed cabinetwork and millwork buildings, their walls truncated to fit

within the new railroad curve. The west end of the lumberyard’s industrial spur

was also re-laid to fit on the inside of the junction connection curve. The lumberyard needed more room for outside lumber storage. But

where? The southeast curve left only a sliver of room in a triangle between the

curve, the Magnolia Branch and the East Belt. The geometry of the 72 degree

diamond crossing of the two rail lines created a somewhat larger triangle of

land inside the northeast quadrant, one made unsuitable for residential use by

the heavier rail traffic, and cut off from the adjacent neighborhood by the

raised grade of the track. Some kind of arrangement was made for the lumberyard

to use the area. Fill dirt was trucked in to bring the area up to rail top level

to allow an easy private crossing from the lumberyard across the southeast curve

and the Magnolia line. It would be used by forklifts carrying long loads of 2x4

studs, some 16 and 18 feet long, so a fairly smooth crossing was needed. During

the time before the fill dirt was graded and asphalted over, neighborhood kids

played in this area when no construction workers were present. Explored, built

forts, etc. That was the occasion in March

1955 for my shooting a picture of my little brother Shelley, neighbor girl

Beverly and a “fort” built of scrap lumber. (This photo,

below left, was on

the first roll of film I ever photographed, at age 10.) In the background beyond

the track, the 3 houses on the south side of Avenue C were left after the

railroad condemned and demolished two houses for the curve. The nearest house

has a horse stable and chicken coops, laid out to fit in the irregular back of

the property left after a portion was cut off by the railroad. Farther back, the

barn-shaped building is my father’s sheet metal fabrication shop on the ground

floor, with a Lionel train layout on the upper floor.

In this photo from 1991 (below right),

the “Brady” sign referred to the crossover, located in the

block south of Brady Street. Before 1970 or so, the East Belt was mostly single

track, but a siding went off to the east of the single main track between

Sherman and Brady, and the north-east quadrant of the Magnolia connection was

accessed through that siding. The siding rejoined the main track just north of

Tower 85, and the siding also accessed the curve from the East Belt to GH&H.

Another siding diverged from the HB&T East Belt main track on the west side

between Sherman and Brady, paralleling the East Belt northward to provide access

to Esperson industrial district between Canal and Navigation. An HB&T

system map from a 1974 Zone Track Spot book seems to label that siding as

“Burris.” The Burris siding and the siding to Magnolia Branch overlapped each

other. Then when the East Belt was doubled tracked, with a second track

continuing the alignment of the Magnolia access siding, it created a crossover,

to which the Brady name apparently refers.

Eventually, the crossing of the East Belt and Magnolia Branch was completely eliminated.

Crossing pulled up and Magnolia Branch west to downtown abandoned and

pulled up. Now a hike and bike

trail. The photo (above left)

is taken standing right in the middle of where the Magnolia Branch tracks USED

to be, and looking straight west down the alignment of the former track.

This photo (above

right) was taken in August 1990

from just south of the dead-end of Avenue C. looking west and it shows what

the northeast quadrant connecting curve looked like for most of the period from

1955 to 2005. Contractor's Supply and Lumber Co. had outside lumber storage in the

open area inside the wye. In the photo, some kind of track alignment check

is being made.

I do not

remember ever seeing any traditional manned 2-story tower at Tower 85, but it

would have been on the east side of Hughes Street. I almost always walked right

along the railroad and saw the tracks and the crossing, and a guardhouse for

entering Hughes Tool. It could have been there and I just missed it. I also

missed ever seeing the MoPac Galveston section of the Texas Eagle passenger

train, even though it was running barely 4 blocks from my home. One thing I DID

see, late 1950s or early 60s… crashed diesel locomotives

from what looked like two trains that got to the crossing at the same time, one

eastbound on GH&H and one southbound on HB&T East Belt. One diesel turned

over on its side, and one standing ON END. At least, that’s my memory as

an early teen...

Thanks for the memories, Kenneth!