Texas Railroad History - Towers 6, 47, 66 and 196 - El Paso

Crossings of the Galveston, Harrisburg & San Antonio, the

Texas & Pacific, the El Paso & Southwestern and the El Paso & Northeastern

railroads

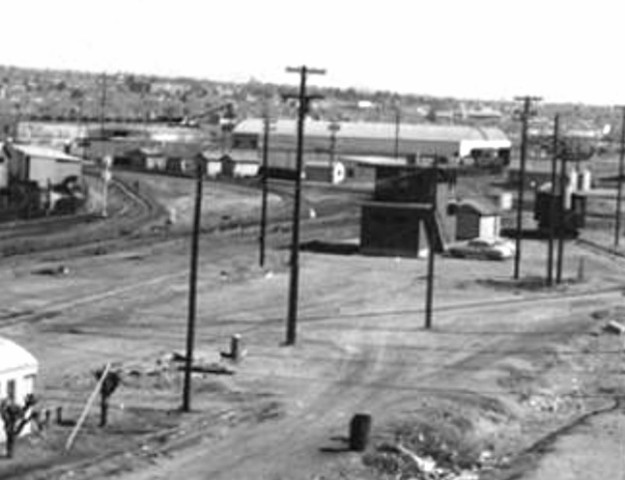

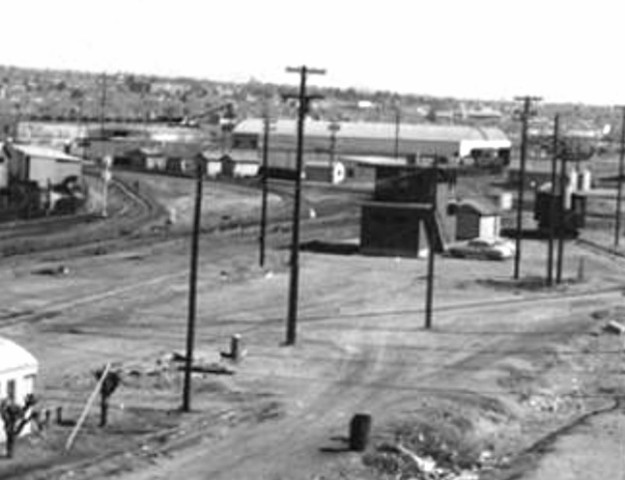

Above Left: The first

interlocking tower built in El Paso, Tower 6, is shown in this image extracted

from a photo taken by railroad executive John W. Barriger III in the 1930s.

Barriger was on the rear platform of his business car facing west as his train

is nearing El Paso Union Depot, taking a connection from El Paso & Southwestern tracks (left)

onto Texas & New Orleans (T&NO) tracks (right.) T&NO was owned by Southern Pacific (SP) and had become (in 1927) the operating

railroad for SP's Texas

& Louisiana lines, including these tracks of Galveston, Harrisburg & San Antonio

(GH&SA) Railway heritage. Above Right: El

Paso's second interlocking tower, Tower 47, is visible near the center of this photo taken by

Barriger on a different trip in the 1930s. His view is northeast along SP

(T&NO) tracks as

his train heads southwest toward Union Depot.

The tracks curving to Barriger's left belong to the El Paso & Northeastern and

they continue north as part of the Rock Island railroad's Golden State Route to

Chicago. It's fortunate that Barriger reflexively photographed every railroad

tower he saw because an earlier photo of Tower 47 he had taken was badly

overexposed. (both photos courtesy John W. Barriger National Railroad

Library)

Below Left:

This image of El Paso's Tower 66 comes from a larger photo taken by Walter H.

Horne in the 1910-1919 timeframe. In the foregound of that photo, the

Green Tree Hotel is visible at the southeast corner of the intersection of San Francisco St. and

what is now S. Coldwell St. (where a parking lot now sits), a location confirmed

by Sanborn Fire Insurance maps of El Paso. This establishes that Horne took the

photo facing east from the six-story high bell tower on the northeast corner of

El Paso Union Depot, directly across the street from the hotel. (photo courtesy DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University)

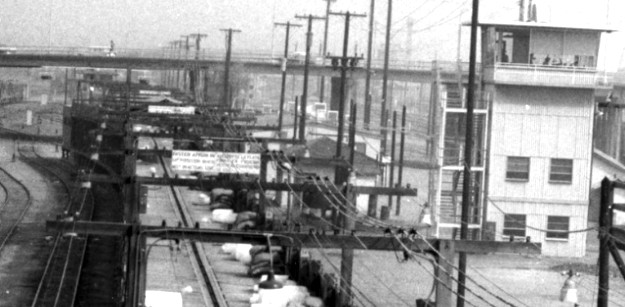

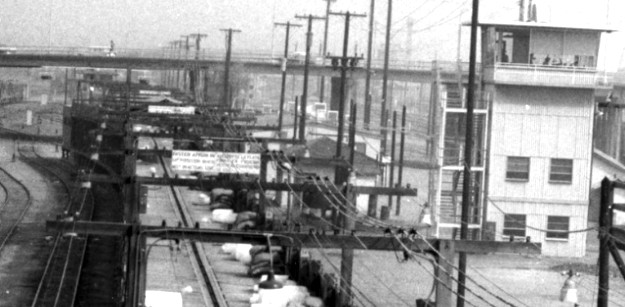

Below Right: In 1950, Tower

196 was built near El Paso Union Depot to replace Tower 6 for managing track

operations throughout the Union Depot's yards. (Daniel Walford photo)

Rails arrived in El Paso in May, 1881 as Southern

Pacific (SP) completed its tracks from California as part of a southern

transcontinental route, though not as originally envisioned. An 1871 Act of

Congress awarded a Federal railroad charter to the Texas & Pacific (T&P)

Railroad (changed to Railway in 1872) and gave

it the right to build from Marshall, Texas to San Diego, California. The Act

also authorized T&P to connect with SP at Yuma, Arizona. When SP's tracks reached Yuma

from Los Angeles in

1877, the T&P was nowhere to be found; its westward construction had

stopped at Fort Worth. The T&P lacked the financing

to lay hundreds of miles of track across the vast and unpopulated west Texas

landscape to reach El Paso, the

next town of any size. Taking advantage of T&P's financial

difficulty, SP continued

building east past Yuma using the right-of-way T&P had surveyed.

T&P objected to SP's move but was in no position to counter it. The Arizona and

New Mexico territorial governments were eager for rail service and they granted

SP permission to build across their states on T&P's planned route.

SP was building to El Paso; it did not, however, have a charter to build into Texas,

and obtaining one from the Texas Legislature was fraught with political peril. A

charter for SP would be opposed vigorously by every Texas railroad, and the

railroads knew exactly how to lobby Legislators with campaign funds. To address this problem, SP Chairman Collis Huntington initiated discussions with

Thomas Peirce (with the unusual ei spelling), President of the Galveston,

Harrisburg & San Antonio (GH&SA) Railway. In 1877, the GH&SA had finished building

to the inland city of San Antonio from Harrisburg, a port on Buffalo

Bayou south of Houston. Huntington wanted Peirce to extend his line westward

from San Antonio to

meet SP in El Paso. The GH&SA had an innocuous provision in its

charter granting permission to build wherever necessary to connect to any

Pacific road. This provision had been included with other GH&SA charter

amendments granted by the Legislature in 1874, a credit to Peirce's visionary

thinking.

Huntington's real objective was to create a transcontinental route closer to

both Mexico and various Gulf ports,

substantially south of T&P's route sanctioned by Congress through Fort

Worth and Dallas. SP planned to use

San Antonio,

Houston, Beaumont and

New Orleans as major waypoints. Huntington proposed to finance the GH&SA's

extension to El Paso knowing that the accumulated debt would later position him

to acquire the GH&SA and its route across Texas. By the summer of 1880, an

agreement with Peirce was in place and SP survey teams were in Texas mapping the

route between El Paso and San Antonio. Huntington also arranged for Peirce to

contract with SP construction forces to continue building east under the

GH&SA charter as soon as SP reached El Paso. Work began east from El Paso in

June, 1881, about the same time the GH&SA began building west from San

Antonio.

With the T&P stuck in Fort Worth for lack of capital, rail

magnate Jay Gould saw an opportunity. He established a syndicate to purchase the

stock of T&P President Thomas Scott for $3.5 million and then formed a

construction company that was hired by the T&P to build the

remainder of the rail line to El Paso. Gould's syndicate agreed to fund

the construction's cash flow in exchange for $20,000 in

T&P stocks and $20,000 in T&P bonds for each mile completed. Gould's

ownership increased with every new mile and he eventually controlled a majority

of T&P stock. In April, 1881, he

took financial control and was named T&P President. The

Dallas Daily Herald of April 27, 1881 reported

that the T&P tracks were "twelve miles west of Colorado City", about

375 miles from El Paso.

A month later on

May 26, Gould filed suit in a New Mexico territorial court claiming that SP had

illegally occupied the right-of-way that had been assigned to the T&P from the

surveys it made pursuant to its Federal charter. A temporary

restraining order was granted by the court to prevent SP from interfering with the T&P's use

of the right-of-way (on which SP track-laying was already complete!) and

preventing SP from claiming a New Mexico land grant promised to T&P by the Federal

government. Gould asked the New Mexico judge to place SP under temporary

receivership and the judge agreed to do so. Gould understood that SP's construction

under the GH&SA charter through El Paso and eastward into west Texas would

result in tracks a hundred miles east of El Paso by the time T&P's crews reached

the vicinity. But Gould also knew that he had a legitimate legal case despite issues

pertaining to T&P's failure to complete construction

in a timely manner. Gould's lawsuit gave

him just enough leverage

for negotiations.

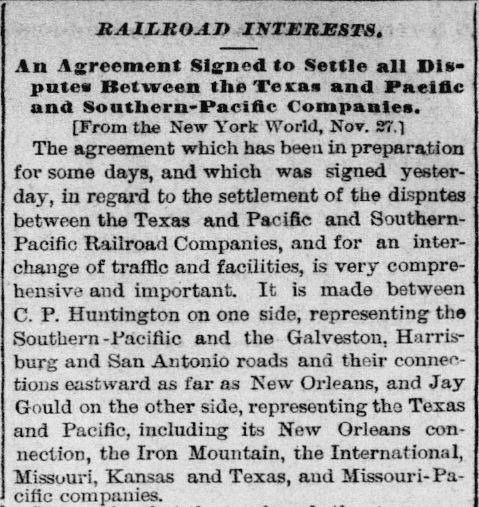

|

Left, Top:

The Galveston Daily News of

December 1, 1881 reported that a deal had been struck between Huntington

and Gould a few days earlier. Huntington gave the T&P rights on the GH&SA tracks into El

Paso in exchange for Gould giving SP all rights and franchises

T&P held west of El Paso. Gould also agreed not

to extend the T&P beyond El Paso.

Right, Top: The same article also announced that the meeting point for the two railroads

would be the new town of Sierra Blanca, 91 rail miles from El Paso. SP

construction crews had reached Sierra Blanca a few days earlier and the T&P rails arrived

on December 1. SP continued building east, reaching Marfa in January and

Sanderson in May. Completion by "June or July next" was overly

optimistic.

Right, Bottom:

The Galveston Daily News of

December 2, 1881 reported that the T&P / SP connection had been made in

Sierra Blanca the prior day. The headline cites "Frisco" as the west

coast destination, no doubt because its population of a quarter million

people

made it

ten times larger than the combined population of Los Angeles

and San Diego. The Sierra Blanca connection opened a new "snow-free"

transcontinental route to the west coast.

Left, Bottom:

The San Antonio Evening Light

of January 12, 1883 reported that SP and GH&SA construction teams

had met at the Pecos River, finishing the San Antonio - El Paso line.

Peirce drove a silver spike signifying completion of a major part of

SP's southern transcontinental route. SP then leased the GH&SA for

several years and eventually acquired it. For its entire route from

California through Texas and beyond, SP

adopted the moniker "Sunset Route", a marketing name Peirce had coined in 1874

that's still in use today. |

|

About the time SP's construction had begun east from El

Paso, the town's second railroad, the Rio Grande & El Paso Railroad, was

completing twenty miles of track between El Paso and the New Mexico / Texas

border. The tracks were to become part of an Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway

line between El Paso and Albuquerque, a line that continues in service today

owned by successor Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF). While Santa Fe's route

to Albuquerque went northwest from El Paso, other investors were planning to

build rail lines northeast from El Paso toward Kansas City and Chicago. A series of

attempts to do so failed to make much progress until the El Paso & Northeastern

(EP&NE) Railroad was founded by Charles Eddy. Eddy's stated objective was to

build to coal fields in eastern New Mexico, 160 miles north of El Paso, but his larger vision was a

connection to the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad in northeastern New

Mexico. After the EP&NE reached the coal fields near Carrizozo in 1899, an additional 128

miles was built to Santa Rosa in 1902 to make a connection with the Rock Island.

This closed the final gap in a route between Chicago and El Paso. On November 2, 1902, Rock Island

and SP collaborated to inaugurate the Golden State Limited passenger

train between Chicago and Los Angeles via El Paso.

Coal was also a motivating factor for the last railroad to reach El Paso. The

investment firm Phelps Dodge had acquired interests in copper mining in Arizona,

an enterprise that required coal to produce coke as a fuel for smelting. Eddy

convinced Phelps Dodge that there was a source of higher grade coal for coking

near Dawson, New Mexico to which his EP&NE was already building tracks. Phelps

Dodge proceeded to buy coal mines near Dawson and began planning a rail route to

reach them from Arizona. Renaming their existing Arizona & South Eastern Railway

to become the El Paso & Southwestern (EP&SW), Phelps Dodge built a new line east from

Douglas, Arizona. It reached El Paso in early 1903 but it did not have a Texas

railroad charter and thus could not build into the state. Anticipating this

problem, the El Paso Terminal Railroad had been chartered in April, 1901. It

built from the Texas / New Mexico border at the Rio Grande River through

downtown El Paso (for passenger service) and continued northeast to central El Paso where EP&SW was building its maintenance shops.

On a

bridge over the Rio Grande, the EP&SW connected to the El Paso Terminal line as a means of entering

the city without a Texas railroad charter in its own name.

In 1901, a state law was passed

giving the Railroad Commission of Texas (RCT) the authority to direct

how crossings of two railroads should be accomplished. RCT held a

hearing in March, 1902 to decide how the El Paso Terminal Railroad would

cross the GH&SA near downtown.

Near Right:

Bryan Morning Eagle, June 3, 1902

Far Right:

Austin Statesman, January 11, 1903 |

|

|

RCT had been forced to decide how the EP&SW (acting through the El Paso Terminal

Railroad) would cross SP's GH&SA tracks west of downtown because the railroads

could not agree. EP&SW wanted a grade crossing with an interlocker while SP

preferred a grade-separated crossing. SP proposed to lower its existing track

ten feet with EP&SW required to build its track twelve feet higher on a bridge.

On April 29, 1902, RCT approved SP's plan for grade separation. Unfortunately for SP, it soon

discovered that the underground geology was much more difficult than expected,

making the estimated time to lower its existing GH&SA track substantially longer than

expected. There appeared to be no feasible way to build a temporary bypass, hence,

all Sunset Route traffic through El Paso would grind to a dead halt during the lengthy period of

construction at enormous cost to SP. The railroads must have approached RCT

immediately to request reconsideration because RCT's new order for an interlocked grade crossing

was issued only 34 days after the original order approving SP's grade separation

plan.

The EP&SW proceeded

to purchase the El Paso Terminal Railroad on February 9, 1903. Near its shops

northeast of downtown, the EP&SW

connected with the EP&NE and then leased it in 1905.

When copper mining took a severe downturn in the early 1920s, Phelps Dodge

leased the EP&SW tracks to SP; the lease did not include the EP&NE. The EP&SW

main line became SP's "South Line" between El Paso and Tucson. SP was able to

acquire the EP&NE in the late 1930s, and in 1955, it acquired all remaining

components of the EP&SW. In 1959, SP began abandonment proceedings for various

track segments including the South Line. It could no longer justify the expense of

maintaining two different routes between El Paso and Tucson.

|

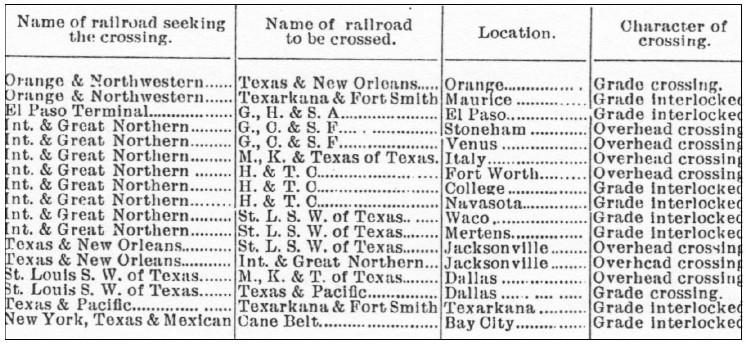

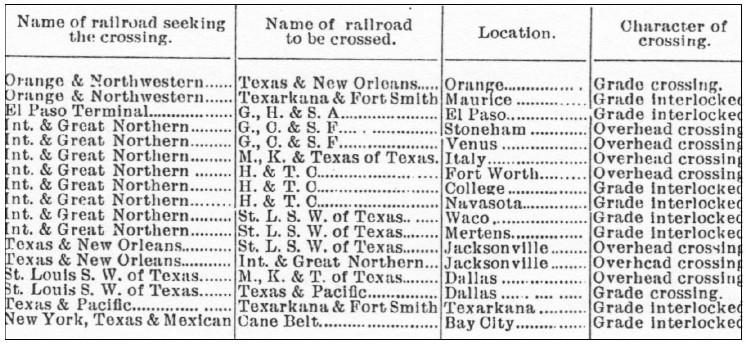

Left: In late

December, 1902, RCT published a table of priority rail crossings, presumably

those to be addressed by RCT in the near future. The table only projected

future activities; it did not include

the first five interlocking towers that had already been placed in

service during 1902 (identified as Tower 1

through Tower 5.) The El

Paso interlocker was included; it was already under construction to comply with RCT's

June order mandating

a grade crossing. The table is confusing; some

interlockers were approved quickly in 1903, e.g.

Waco, "College",

Navasota

and Orange, while others were delayed for many years, e.g.

"Maurice" (Mauriceville

in 1929) and

Mertens (c.1935).

At the end of 1903, RCT began publishing a comprehensive table of active interlockers (a

practice it would continue annually through the end of 1930.) These tables did not

include overhead crossings since no interlocker was required.

Interlockings under construction were included, but the tables did not

project future interlockers. In the December, 1903 table, RCT

listed the GH&SA / EP&SW crossing as

Tower 6 commissioned on January 23, 1903 with a

17-function / 17-lever mechanical interlocking plant built by Union Switch &

Signal Co. |

Above: This Barriger photo of Tower 6 was numbered by

him as SP1453, but it was not taken from the rear platform of his business car.

Barriger had numbered his earlier photo of Tower 6 (at

top of page) as SP1451, but his photo numbered SP1452 (below)

faces east, a direction he could not see from the rear platform of his eastbound

train. Barriger had apparently disembarked at Union Depot and then walked along

the track toward Tower 6, turning to take the photo (below) of El Paso Union

Depot before he took the above photo of Tower 6. The tracks visible beyond the

crossbuck at far left belong to Santa Fe, and they continue behind (and below)

Tower 6 to proceed north to Albuquerque. In the photo

below, note the bell tower on the northeast corner of Union Depot from which the

photo of Tower 66 (at top of page) was taken. Tower 66 had been decommissioned

in late 1928 and was no longer standing at the time of Barriger's trip.

| Right:

In January, 2022, Google Street View captured this view of El Paso Union

Depot and its bell tower taken from the east side of the station on San

Francisco Street, facing the opposite direction from Barriger's photo. The

fenced parking lot on the corner at left was home to the Green Tree

Hotel when Horne took his photo of Tower 66 some two decades before

Barriger's photo. It is apparent that the bell tower has been

substantially altered since Barriger's day. El Paso Union Depot remains

in use for passenger service by Amtrak. |

|

Explicit proof of which railroad took the lead in

designing Tower 6 has not been found, but it was undoubtedly SP. Tower 6

resembles Tower 3 built by SP which opened three

months earlier. Tower 6 may have been the last SP tower built in Texas that did

not have the distinctive fishscale pattern familiar in Queen Anne

architecture and common to SP's later towers, e.g. Tower 13,

Tower 16, Tower 17 and

Tower 21, all of which opened within seven months

of Tower 6 (plus many others that SP built in subsequent years.) It seems likely

that the El Paso Terminal Railroad's crossing at Tower 6 was not built until 1902,

after the 1901 state law granting RCT authority to mandate and approve

interlocker installations. As such, the law required the second railroad (here, the El

Paso Terminal) to pay the capital cost of the tower and its interlocking plant.

That rule did not, however, require the El Paso Terminal to take the lead for

design and construction of the tower; this was negotiated between the railroads. SP

had experience building interlocking towers and undoubtedly took the lead for procurement and installation

of the interlocking plant and associated signals, derails and switches, but with

capital funding provided by EP&SW through the El Paso Terminal's books. Had

this been a pre-1901 crossing, the capital

outlay would have been shared equally.

Once a tower was commissioned for operations by RCT, the recurring

expenses for materials, utlities and employee labor to staff operations and

maintenance (O&M) were shared by the railroads that crossed at the

interlocking, typically on a weighted function

basis (the precentage of an interlocker's total functions used by each railroad.) One

railroad would take the lead in providing O&M staffing and would bill the

other(s) on a periodic basis. RCT did not begin publicly identifying the lead

railroad for O&M staffing at each tower until it published its interlocker table dated October 31, 1916. That document listed the

GH&SA with the reponsibility for staffing Tower 6. In most cases, the company

with responsibility for staffing was the company that had taken the lead for design and

construction.

|

The El Paso Terminal Railroad track that EP&SW purchased went east

to downtown,

curved northeast and continued to the maintenance shops. It connected

nearby with the EP&NE which had its own line into downtown for passenger

service at SP's depot, particularly the Golden

State Limited. The end result was a junction about a mile and half

northeast of downtown through which each of these railroads passed. The

T&P was also there, sharing SP's line from the east but building tracks

from the junction to reach its own freight yard to the south plus

other connecting tracks and industry spurs. The

junction needed an interlocking plant which RCT authorized as

Tower 47.

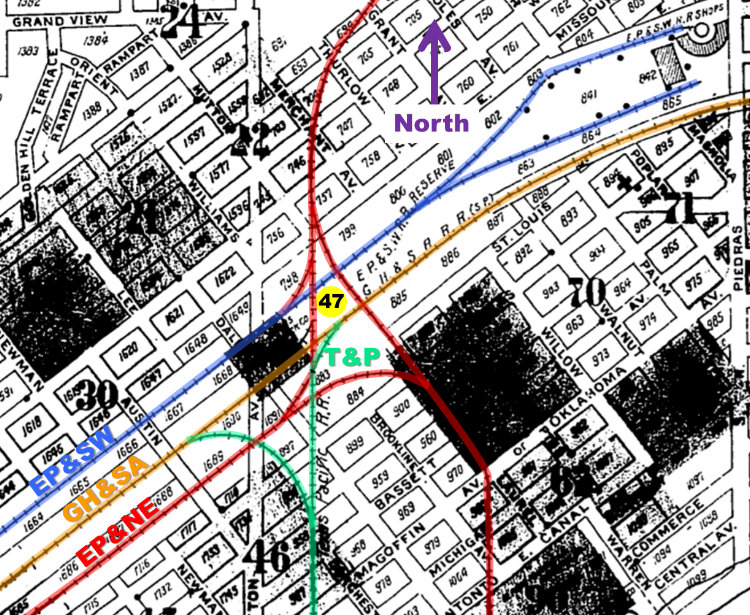

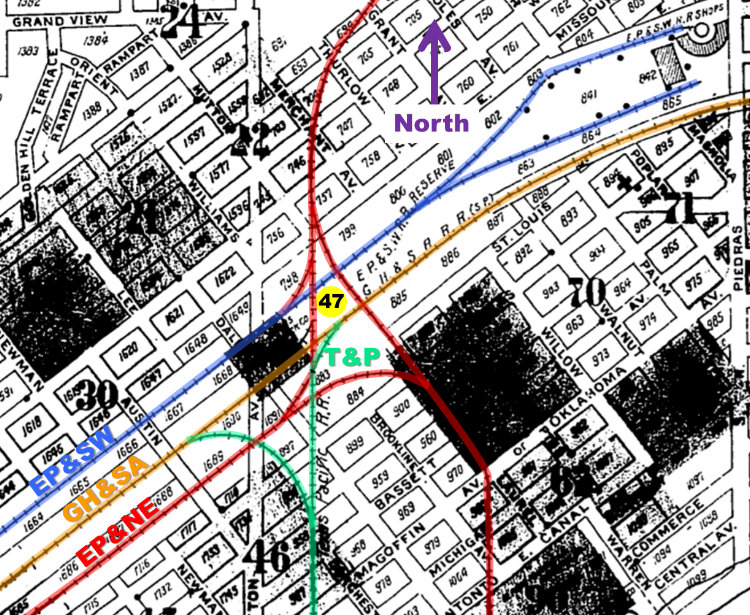

Left: This image from

the index of the 1908 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map of El Paso has been

annotated to show the rail junction where Tower 47 was located near

various freight yards a mile and a half northeast of downtown. It was

commissioned for operation by RCT on July 11, 1904 with

the participating railroads

being the GH&SA, the T&P and the EP&NE. By 1916, the interlocker

function count had increased from 25 to 31 functions. Another increase

to 60 functions is noted in the report for 1923. In 1927, EP&SW

officially replaced EP&NE as a contributing railroad, and by 1928, ten additional

functions had been added, bringing the total to 70. The EP&SW had

tracks past the tower and had leased the EP&NE in 1905, but it was not

listed by RCT at

Tower 47 until 1927. Perhaps its tower expense share had been merged

with EP&NE's since the lease was likely in work by the time Tower 47

opened.

Santa

Fe's tracks were mostly south of Tower 47, off the bottom of the

map near the Rio Grande River, so it was not formally involved with Tower 47. Santa

Fe's tracks were mostly south of Tower 47, off the bottom of the

map near the Rio Grande River, so it was not formally involved with Tower 47.

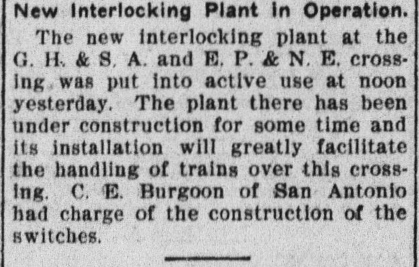

Left:

El Paso Sunday Times,

July 10,

1904 |

El Paso Union Depot opened in February, 1906 to

consolidate passenger operations for all railroads. Tower 6 was

effectively the west control point for trains entering and leaving the Union

Depot yards. At some point, Santa Fe began accessing the Union Depot on SP's tracks

through Tower 6 (per Santa Fe timetable dated June 6, 1926.) Traffic growth through Union Depot motivated construction of an

additional interlocking to control the east entrance to the yards and depot. On

April 23, 1906, a proposal was submitted to RCT to build a new tower for the "east

end of the El Paso Union Depot grounds". The proposal was accepted;

construction commenced and the

newly designated Tower 66 was placed in service on November 8, 1906.

Above Left: The

El Paso Daily Times of August 1, 1906

carried this item noting the beginning of construction of the new (Tower 66)

interlocker at the "...east end of the union station yards..."

Above Center: The

El Paso Daily Times of November 8, 1906

reported that the new tower was expected to be commissioned very soon (and in

fact, it occurred the same day the article appeared.) Unfortunately, the author

has the geographic directions reversed: the new tower controlled the

east end of the yards, not the

west.

Above

Right: Only nine days later, the

El Paso Daily Times of November 17, 1906 was already reporting that train crews

operating at night were grumbling about the inability of the Tower 66 operators to

recognize their signals. Whistle codes for locomotives operating at Tower 66

were established, but whether they were in place by this time (and if

so, how they contributed to the problem and its solution) is undetermined.

Unfortunately, Tower 66 initially created more problems

than it solved. After only six days of operation, Mr. H. J. Simmons, General

Manager of El Paso Union Depot, wrote a letter to RCT requesting modifications

to Tower 66, explaining that the Depot had "experienced great delays to train and

switching movement since the inauguration of the interlocking." This letter is

in the Tower 66 file in the RCT interlocker archives maintained at DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University, but there is no follow-on

correspondence to explain whether any changes were approved. When Tower 66

commenced service, the interlocking plant had

15 levers dedicated to 22 switches and 10 locks, 7 levers controlling 12 facing

point locks, and 15 train signals controlled by 15 levers, a total of 37 levers

with 3 spares available in the 40-lever frame.

|

|

Above Left: The 1908 Sanborn

Fire Insurance Map of El Paso shows Tower 66 as a rectangle (near the upper left

corner)

between the GH&SA tracks (lower) and the EP&SW tracks (upper.)

It was near the intersection of San Francisco St. and S. Durango St. Magnification

reveals it labeled by the cartograhper as a 2-story "S.P.

Signal Ho" (house). The crossing track to the right of the tower is the EP&SW

passenger lead, and there were numerous other Union Depot yard tracks not shown on the map.

The depot is a couple of blocks farther west (left) off the map. SP employee

timetables from the 1920s list Tower 6 at Milepost 830.9 and Tower 66 at

Milepost 830.4, placing Tower 66 approximately one-half mile east of Tower 6.

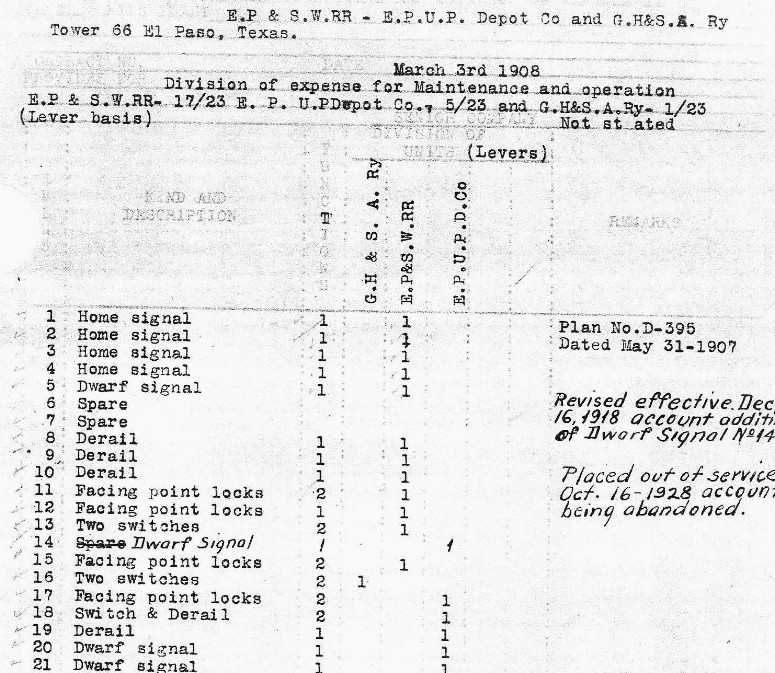

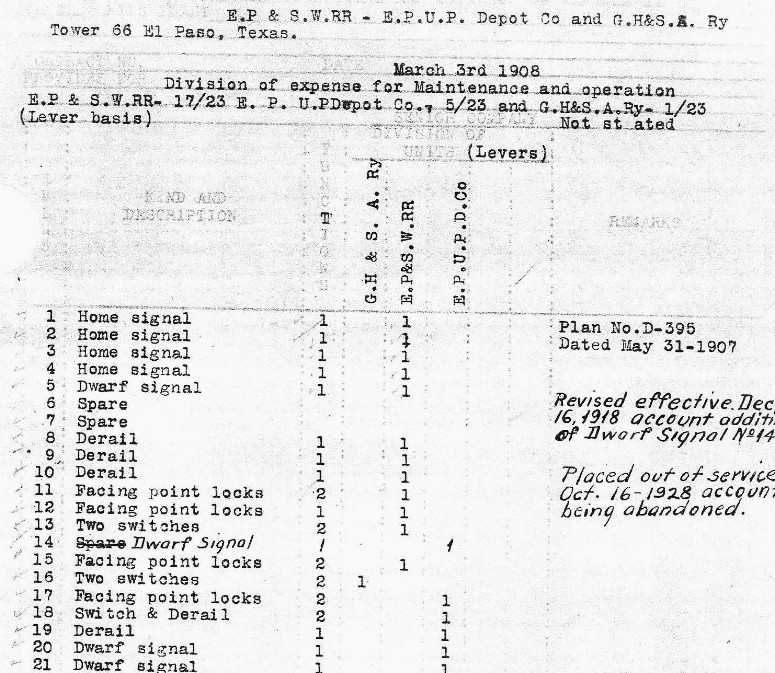

Above Right: This image is extracted from an SP document (Carl Codney collection) that recorded the division of expenses for Tower 66

among the EP&SW, the El Paso Union Depot Co. (which provided yard switching

services) and the GH&SA. Expenses were divided on the basis of the number of

levers applicable to each railroad out of the total of 23 levers in the

interlocking plant (which differs from the initial 37 levers documented in the

RCT interlocker archives.) The percentages were applied to all O&M expenses associated

with the tower. The document is based on a plan established in May, 1907 and it

was revised by hand in 1918 when Dwarf Signal No. 14 was added.

In a letter to RCT dated May 18, 1928, SP proposed changes to Tower 66's

interlocking plant including moving its controls into Tower 6. The changes were

approved by RCT and the work was accomplished over the summer, enabling Tower 66

to be abandoned on October 16, 1928. The fate of the Tower 66 building

is undetermined.

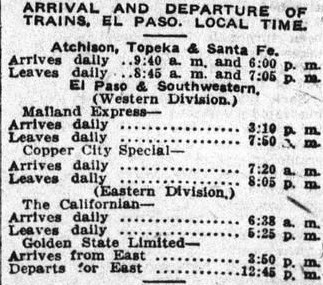

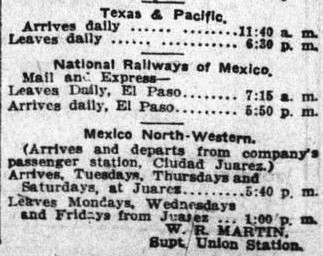

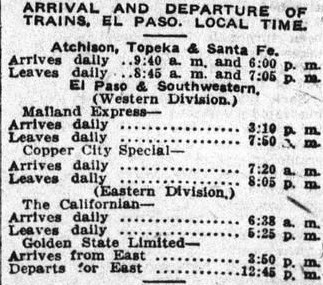

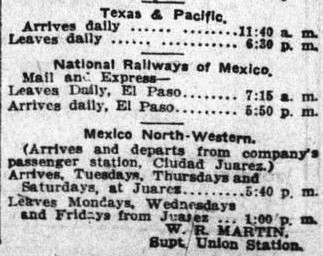

Right: This Union

Station Time Card from the June 11, 1912 issue of the

El Paso Morning Times provides a

glimpse of a typical day at Union Station. It is interesting that

although SP owned the GH&SA, their trains were listed separately as

GH&SA service only went east from El Paso. In addition to the single

daily train of the National Railways of Mexico that operated into Union

Station, the schedule also shows Mexico North-Western service at a

passenger station across the river in Ciudad Juarez. |

|

|

|

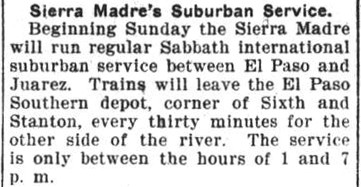

| Right: Prior to 1909, the

Mexico North-Western referenced in the Union Station Time Card had been known officially as the Rio

Grande, Sierra Madre & Pacific Railway, but locals simply called it the

"Sierra Madre". It operated "suburban services" between El Paso and

Ciudad Juarez through its subsidiary, the El Paso Southern (EPS) Railway

chartered in 1897. This item from the El Paso

International Daily Times of December 6, 1901 announced new

Sunday suburban service every half hour between 1:00 pm and 7:00 pm. The

implication is that the suburban service did not normally operate on

Sundays, but the railroad had decided to begin offering it for Sunday

worship. Electric streetcars began operating between the two cities in

1902. |

|

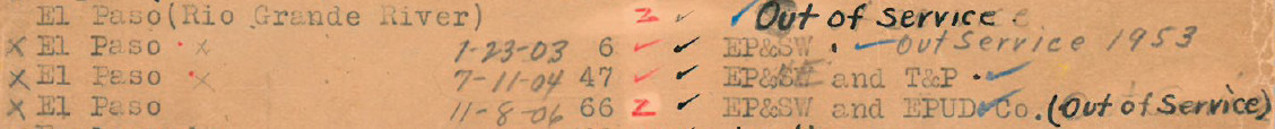

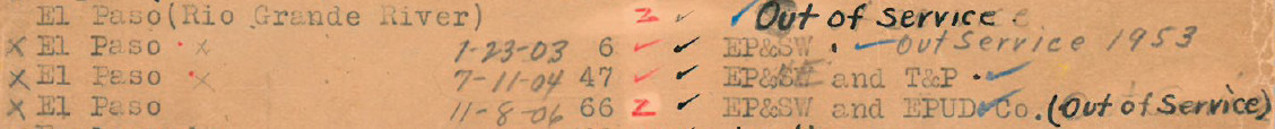

The

El Paso Daily Times article of August 1,

1906 (referenced further above) mentions the Santa Fe and the Mexican Central railroads, stating...

"It is said that the union depot company will soon build an interlocking

plant to handle the trains of the latter two companies." This statement is

significant in light of the image snippet

below which comes from a 3-page SP document

(Carl Codney collection) that lists all of the interlocking plants in Texas (by

alphabetical location) with which SP had some involvement. The document was originally

created sometime prior to December 17, 1930 because that date appears on the

first page in a handwritten legend explaining the meaning of various red marks

(relevant here, 'z' meant "out of service" and a red check meant "operated by

T&NO".) The blue checkmarks are associated with a handwritten date, "10-20-48",

apparently the date a status update for each interlocker was made on the

document. The black check marks and the penciled 'x' marks are undefined. The

penciled dates identify when interlockers were commissioned for service by RCT.

This snippet clearly

implies that an unnumbered and undated interlocker at El Paso existed at some

point in time near the Rio Grande River and that SP was involved (else it would

not have appeared on this list.) Among the seventeen entries in this document

that do not have RCT tower numbers, this is the only one that lists neither a

special purpose (e.g. "drawbridge", "junction", "passing track") nor the

involvement of any other railroad. It merely says "Out of Service" (as do the

stray pencil marks beneath it.) The lack of a special purpose could imply that

it was simply a basic interlocker, albeit an unnumbered one without an

identified crossing railroad. Note also that while Tower 196 is not listed on this snippet, it

was handwritten elsewhere on the document with

a date of "11-1-50".

This snippet clearly

implies that an unnumbered and undated interlocker at El Paso existed at some

point in time near the Rio Grande River and that SP was involved (else it would

not have appeared on this list.) Among the seventeen entries in this document

that do not have RCT tower numbers, this is the only one that lists neither a

special purpose (e.g. "drawbridge", "junction", "passing track") nor the

involvement of any other railroad. It merely says "Out of Service" (as do the

stray pencil marks beneath it.) The lack of a special purpose could imply that

it was simply a basic interlocker, albeit an unnumbered one without an

identified crossing railroad. Note also that while Tower 196 is not listed on this snippet, it

was handwritten elsewhere on the document with

a date of "11-1-50".

The existence of this Rio Grande River interlocking

fits well with the reference to a plant expected to

handle Santa Fe and Mexican Central trains for which the construction work was

to begin "within a few days" of the August 1, 1906 publication

date of the article. The Mexican Central operated across an international rail

bridge (the 1905 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map of El Paso shows two such bridges)

to access Union Depot. Santa Fe may also have crossed into Mexico on occasion,

and SP is known to have used an international bridge through its association

with the EPS, which owned two miles of track crossing the river. At some point,

SP began providing EPS with switching services. EPS was acquired by EP&SW in

1954 and then merged into SP in 1961. Perhaps the interlocker was an EPS

crossing of Santa Fe's tracks near the river and had been incorporated on this document's

initial version (it is typewritten) due to SP's involvement with the EPS. This

might have been maintenance support for the interlocker or some other

relationship. Such a crossing is evident on Sanborn index maps,

but there are others that could have been candidates for

an interlocker near the river. Unfortunately, Sanborn did not draw detailed maps in these

areas so there is no direct evidence of any tower or cabin structure. No other

specific references to the Rio Grande River interlocking have been

found.

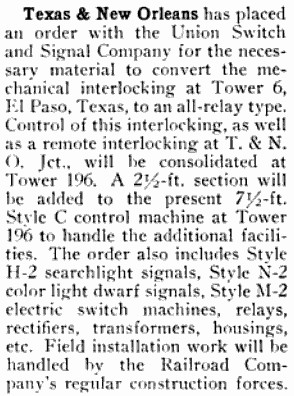

|

Left: This

entry in a table titled "Interlocking Plants Completed in 1921" was

published in Railway Age,

January 7, 1922. Might it pertain to the Rio Grande River interlocker?

The numbers are counts of mechanical levers and the footnotes mean

"approach, detector and/or route locking". RCT records list no new

numbered interlockers completed in El Paso in 1921. |

Why was the Rio Grande River interlocker

not assigned a number by RCT? The article says

that it will be built by "the union depot company ... soon", and in the early years of

interlocker deployment, railroads did not always notify RCT of interlockers they

installed for their own purposes within their

own yard limits, particularly if no other railroad was involved. This issue first

arose with RCT in the context of the approval of Tower

116 at Houston Union Station wherein the Houston Belt & Terminal Railroad

argued that since it owned all of the tracks at Union Station, there simply was no other

railroad involved (and thus, by their interpretation of state law, no jursidiction for RCT)

although the tracks were used by other railroads. This

argument was nixed permanently in the mid-1920s when RCT required Santa Fe to

request approval of its yard interlocker at Canyon

where there were no other railroads involved, neither as track owners nor

visiting trains.

|

Union Depot yard tracks remained under the control

of Tower 6, but by 1950, the tower's wooden

structure was nearly fifty years old. No evidence has been found to

suggest that it had ever been rebuilt. As the El Paso Union Depot

facility and yards continued to see increasing traffic, the decision to rebuild Tower 6 was made with the idea of

relocating it closer to Union Depot. This led to construction of Tower

196 to house the interlocking plant and its operational controls. The

new tower number was assigned because the two facilities overlapped

operationally for perhaps a year after Tower 196 opened on November 1,

1950. The site selected near Union Depot was about halfway between Tower

6 and the former site of Tower 66.

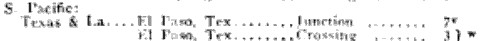

Left: This news item from

The Signalman's Journal of March,

1951 discusses SP's plans (through its T&NO operating railroad) to

convert the Tower 6 interlocking plant to an electric relay system. Its

controls (and presumably its new eletric interlocking plant) were to be

integrated into Tower 196. The article states that Tower 6's current

interlocking plant is mechanical and it also states that there is a

"7-1/2 ft. Style C control machine at Tower 196". The implication is

that when Tower 66 was closed in 1928, its existing mechanical

interlocking plant was eventually replaced by a new electric plant

installed at Tower 6 to cover the Tower 66 functions. That plant (with

updates over the years) was then relocated to Tower 196 to control the

functions previously managed by Tower 66. This allowed Tower 196 to

commence operations while the planning proceeded for an electric

interlocker to replace Tower 6's mechanical plant.

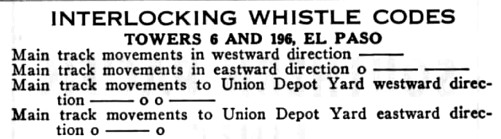

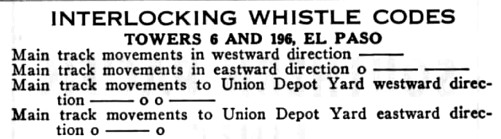

Left: This December 1,

1951 T&NO San Antonio Division Special Instruction shows

whistle codes common to both towers. This likely indicates that the

operational demise of Tower 6 was anticipated in the near future, prior

to the next timetable publication, hence the codes would apply to Tower

196 once Tower 6 was no longer operational. |

Below: Jimmy Barlow notes

that Google Street View shows Tower 196's ultimate demise occurred sometime

between September, 2015 (below left) and

April, 2017 (below right).

Above: The tower in this Barriger photo

can be confirmed as Tower 47 by the nearby "Consumers Ice & Fuel Co." building to the right, a

business that now operates as "Reddy-Ice" in El Paso. This view is looking south

on the El Paso & Northeastern with the El Paso & Southwestern crossing in the immediate

foreground, and the boxcars in the distance (to the left of the tower) probably

on the GH&SA tracks behind the tower. (John W Barriger III National Railroad

Library)

|

Left:

This

Consumers Ice & Fuel Co. facility (blue dashes) was captured by Barriger

in the above photo of Tower 47. |

|

Left: The ice

facility still stands, now doing business as "Reddy Ice". On the front of the building

beneath the peaked roof, the faded original painted sign

remains visible. Tower 47 was roughly a thousand feet

north-northeast of the ice facility. (Google

Street View, February, 2020) |

Above: Facing northeast, this

Barriger photo shows Tower 47 sitting beyond the Cotton Ave. grade crossing

(which is guarded by a crossing control tower at right.) Cotton Ave. is now an

overpass that appears to track the original roadway alignment. The Consumer's

Ice & Fuel facility is about 500 ft. to Barriger's right. (John W Barriger

III National Railroad Library)

Above: Like Tower 6, Tower 47 eventually needed to be rebuilt.

Unlike Tower 6, the new brick Tower 47 was built

adjacent to the original tower, keeping the same tower

number. These images were extracted from photos taken from the Cotton Ave. overpass in March, 1960 by Ernest Hoppock. The

brick tower dates to sometime in the 1950s. (Special

Collections, University of Texas El Paso)

Below: These two photos of the brick Tower 47 were taken by

Ernie Leggett in 2006. The Cotton Ave. overpass is visible in the image below

right.

Google Street View

narrows the timeframe in which the brick Tower 47 was removed to between August,

2015 (above) and April, 2017 (below).

Above Left: This map from a 1954

"re-print" (incorporating numerous updates) of the 1908 Sanborn Fire

Insurance map set of El Paso shows a rectangle along the left edge of the image

labeled as a 4-story "Switch Tower". This is undoubtedly the

same yard tower seen in the image above right

derived from a photo

taken in 1960 with the Cotton Ave. overpass in the background. This yard tower

was not included in RCT's tower numbering system; most yard towers weren't

although a

few were (e.g. Tower 117,

Tower 121, Tower 199.) The tower probably had switch and

signal controls for the yard but no interlocker. Tower 47 is very likely the rectangle at the right edge of the

Sanborn map,

but the label is illegible. (photo courtesy Cornell University

Library.)

Santa

Fe's tracks were mostly south of Tower 47, off the bottom of the

map near the Rio Grande River, so it was not formally involved with Tower 47.

Santa

Fe's tracks were mostly south of Tower 47, off the bottom of the

map near the Rio Grande River, so it was not formally involved with Tower 47.

This snippet clearly

implies that an unnumbered and undated interlocker at El Paso existed at some

point in time near the Rio Grande River and that SP was involved (else it would

not have appeared on this list.) Among the seventeen entries in this document

that do not have RCT tower numbers, this is the only one that lists neither a

special purpose (e.g. "drawbridge", "junction", "passing track") nor the

involvement of any other railroad. It merely says "Out of Service" (as do the

stray pencil marks beneath it.) The lack of a special purpose could imply that

it was simply a basic interlocker, albeit an unnumbered one without an

identified crossing railroad. Note also that while Tower 196 is not listed on this snippet, it

This snippet clearly

implies that an unnumbered and undated interlocker at El Paso existed at some

point in time near the Rio Grande River and that SP was involved (else it would

not have appeared on this list.) Among the seventeen entries in this document

that do not have RCT tower numbers, this is the only one that lists neither a

special purpose (e.g. "drawbridge", "junction", "passing track") nor the

involvement of any other railroad. It merely says "Out of Service" (as do the

stray pencil marks beneath it.) The lack of a special purpose could imply that

it was simply a basic interlocker, albeit an unnumbered one without an

identified crossing railroad. Note also that while Tower 196 is not listed on this snippet, it