Texas Railroad History - Tower 134 - Houston (Pierce

Junction)

A Crossing of the Galveston, Harrisburg & San Antonio Railway

and the International & Great Northern Railroad

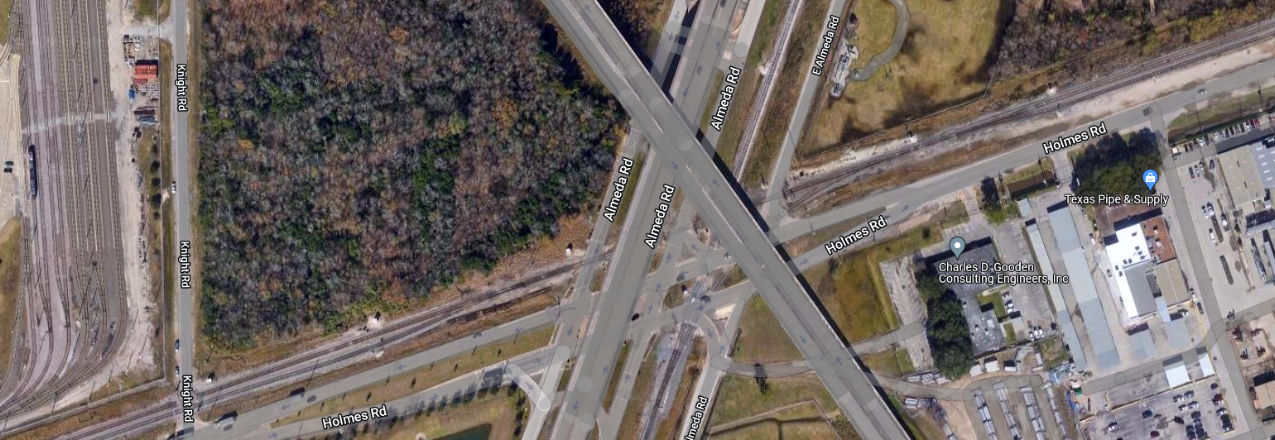

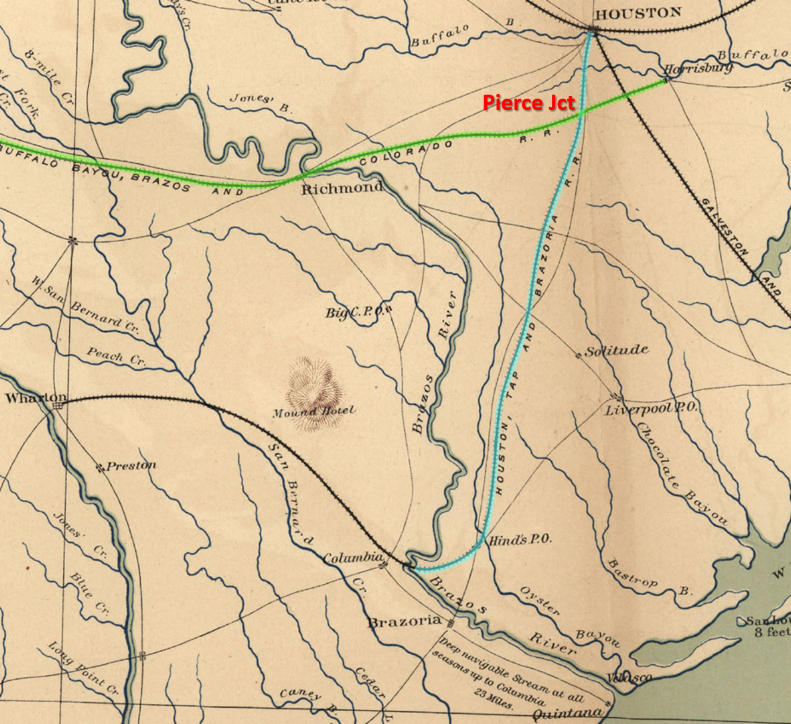

Above:

This image taken from an 1865 map has been annotated to highlight two railroads: the Houston Tap & Brazoria

Railway (HT&B, blue) and the Buffalo Bayou, Brazos & Colorado Railway

(BBB&C, green). The settlement that grew up around the crossing of the two

railroads became known as Pierce Junction. Although the HT&B charter planned for a crossing of the

Brazos River at Columbia, neither the bridge nor the extension to Wharton was

ever built. The HT&B terminated at East Columbia on the east bank of

the river, and the town of Columbia (the first capital of the Republic of Texas)

eventually became known as West Columbia. The close association of the HT&B with

this important river port led to the railroad being nicknamed "Columbia Tap", a

title that has persisted more than 150 years. (from the

Atlas to Accompany the Official

Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, DC: Govt. Print.

Off., 1895, courtesy of the Texas Transportation Archive)

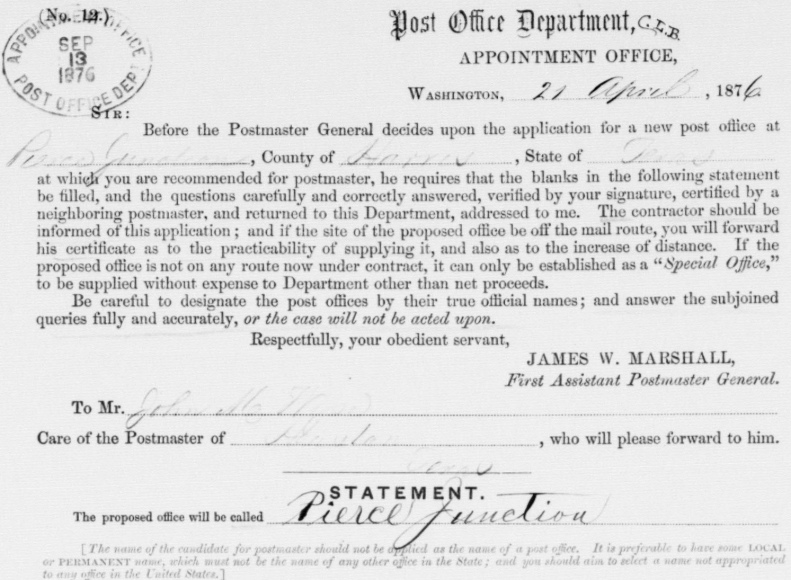

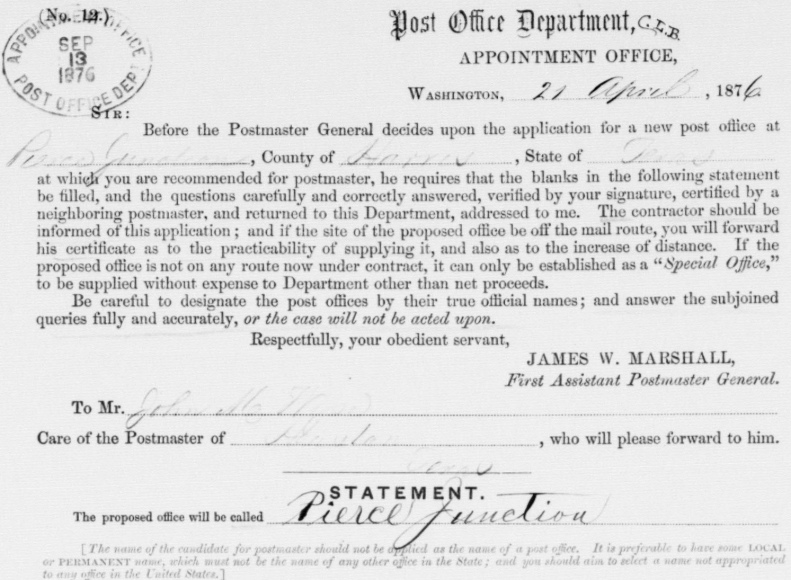

Below: The top portion of the

one page application for a post office at

Pierce Junction shows that it was initially filled out on April 21, 1876.

After the form was completed, certified and mailed to the Post Office

Department, its Appointment Office stamped its receipt of the application

on September 13, 1876. (National Archives)

The first railroad in Texas, the Buffalo Bayou, Brazos

and Colorado (BBB&C) Railway, began construction in 1851 at

Harrisburg, a small port on Buffalo Bayou

a few miles downstream from Houston. The objective

was to build west to the vicinity of the Colorado River near Columbus. From

there, the railroad would build north

and west,

following the river to La Grange and Austin but never crossing it. The endpoint for the first track segment

(completed in 1853) was Stafford's Point (now the Houston suburb of Stafford), approximately

twenty miles west of Harrisburg. By 1855, twelve additional miles had been built

to Richmond, the county seat of Fort Bend County, on the west bank of the

Brazos River. As traffic on the BBB&C increased, merchants in Houston noticed

that much of the trade brought into Harrisburg by rail was going south on

Buffalo Bayou to Galveston rather than north on the bayou to Houston. They

successfully pursued having the Legislature amend the BBB&C's charter to

authorize the City of Houston to issue bonds for a rail line to "tap" the BBB&C.

Funded by Houston's bond money, construction of the Houston Tap Railroad

commenced in April, 1856 and operations began in October. The

connecting point of the two railroads was 6.5 miles south of Houston, and was known

simply as "Junction", the first railroad junction in Texas.

Owners of the

vast sugar and cotton plantations south of Houston realized that an extension of the Houston Tap's

rails south from Junction would give them the transportation options they

sorely lacked. Thus, before the Houston Tap had even begun operations, the

Houston Tap & Brazoria (HT&B) Railway was granted a charter by the Legislature

authorizing it to acquire the Houston Tap and extend its rails south to

Columbia. Columbia was a major port on the Brazos River close enough to the Gulf

of Mexico (about 23 river-miles at the time) that navigation by ocean-going

steamships was generally feasible year round. The acquisition was consummated in

June, 1858 and

HT&B trains were operating to Bonney, 25 miles south of Junction, by the end of the

year. Rails reached East Columbia in 1860, about 45 miles south of

Junction. East Columbia was on the east bank of the Brazos River across from

Columbia, the first capital of the Republic of Texas. The close association of

the HT&B with Columbia resulted in the rail line's nickname, "Columbia Tap",

which has persisted to the present day. With rail service, East Columbia's

population and commerce grew, gradually causing Columbia to become identified as

West Columbia. In 1873, the HT&B was acquired by the International & Great

Northern (I&GN) Railroad, the largest railroad in Texas at the time, but the

rails never crossed the Brazos into West Columbia.

At Arcola, thirteen miles south of Junction, Thomas W. Peirce

owned a large sugar plantation. Peirce was a wealthy mercantile businessman and attorney from

Boston who used the uncommon ei spelling of his last name. The Columbia

Tap gave Peirce's plantation access to barges and steamboats at East Columbia,

and also provided a route to the port of Harrisburg via the connection with the

BBB&C at Junction. Since much of his wealth had been derived from exporting

Texas products, particularly cotton and sugar, Peirce had become interested in

the development of railroads in Texas. By 1857, he had become a director of the

Houston & Texas Central (H&TC) Railway and had also performed legal work for the

BBB&C.

Although

the BBB&C had built 48 miles beyond Richmond to the tiny community of Alleyton

three miles east of the Colorado River, economic malaise during Reconstruction

put the railroad into receivership. In a lawsuit for non-payment, the contractor that had

built it, William Sledge, acquired the BBB&C and then made a valiant attempt to continue

its operations and restart construction toward La Grange. Peirce saw an

opportunity, and in 1870, he formed a small investor group that purchased the

BBB&C from Sledge. He petitioned the Legislature to modify its charter to

authorize building to San Antonio instead of La

Grange. Although the charter retained a requirement to build a branch line

to La Grange (which Peirce fulfilled in 1881), the Legislature granted his

request to build to San Antonio. Peirce also asked that the

railroad's name be changed to the Galveston,

Harrisburg and San Antonio (GH&SA) Railway. Peirce bought out most of the other

investors and initiated construction westward. As part of his efforts to publicize his

railroad, Peirce coined the term "Sunset

Route", a name still in use today.

Newspapers

began referencing the GH&SA as "the Peirce Line"; the community

that grew up around Junction appears to have begun using the name "Peirce Junction"

as a result. The

earliest appearance of

"Peirce Junction" in the Galveston Daily News

("Circulation More Than Double That Of Any Paper In Texas") is September 8, 1874.

Both "Pierce Junction" and

"Pierce's Junction" (using the normal spelling) also began to appear in the

Galveston newspaper but not before July 3, 1875.

Newspapers

began referencing the GH&SA as "the Peirce Line"; the community

that grew up around Junction appears to have begun using the name "Peirce Junction"

as a result. The

earliest appearance of

"Peirce Junction" in the Galveston Daily News

("Circulation More Than Double That Of Any Paper In Texas") is September 8, 1874.

Both "Pierce Junction" and

"Pierce's Junction" (using the normal spelling) also began to appear in the

Galveston newspaper but not before July 3, 1875.

Left: The

Galveston Daily News of Sept. 21, 1875

reported on the aftermath of a storm at Pierce Junction.

The Peirce Junction name had probably been in use for only a couple of

years when John M. Wyse filled out the official application requesting a new

post office for "Pierce Junction". The handwriting is consistent

throughout the application, suggesting that

Wyse personally entered the normal spelling of "Pierce". Whether he did so of

his own volition or as a result of a community-wide decision is lost to history.

Wyse dated the application April 21, 1876 and answered a series of questions

pertaining to the location of the proposed post office and the populace it would

serve. Wyse was required to have the application certified by the postmaster at

the nearest post office, Houston, which was accomplished on September 8, 1876. It was mailed to the Post Office Department,

which stamped it as received by the Appointment Office on September 13. Among the details supplied by Wyse on the completed

application... the Contractor that operated the mail route was the GH&SA; the post

office would be located "north side 40 feet from RR track"; and the population

to be served numbered "about four hundred." The post office

was granted, but it lasted on a couple of years before being decommissioned,

presumably for insufficient activity.

|

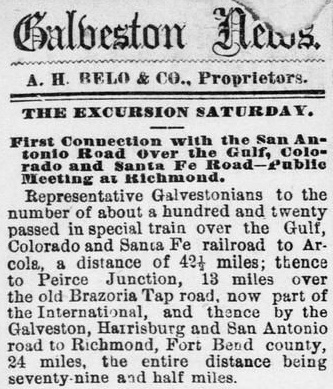

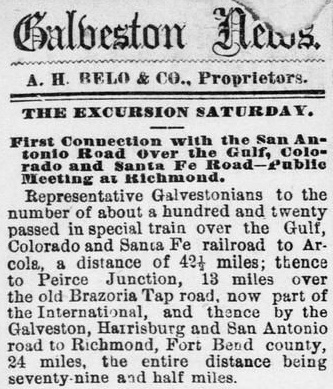

Left:

The author of this article in the Galveston Daily

News of April 30, 1878, didn't get the memo. A year and a half after

the Pierce Junction post office had been granted, the reporter still

used the "Peirce" spelling when describing the route of a special

excursion train out of Galveston. The Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe

(GC&SF) Railway had finally reached

Arcola, reason enough for 120 "Representative Galvestonians" to

celebrate with an excursion. The

reporter explains that the train turned north at Arcola, went

13 miles to "Peirce Junction", and then turned west and proceeded to

Richmond on the GH&SA, the terminus of the day's trip. At Arcola,

the GC&SF would eventually build across the Columbia Tap (called

"Brazoria Tap" in the article) and continue west to Richmond and beyond, founding

Rosenberg in the process.

The improper

"Peirce" spelling no longer appeared in the

Galveston Daily News after

September 25, 1888. |

The GH&SA's rails reached San Antonio in 1877, and

within a year, Peirce and Southern Pacific (SP) Chairman Collis Huntington were

discussing a potential partnership regarding the line SP was building east from California to

Yuma, Arizona. Huntington had decided that SP construction would continue past Yuma all the way

to El Paso, and he had obtained permission from the territorial governments of

Arizona and New Mexico to do so. Huntington wanted to create a southern

transcontinental route close to Mexico via El Paso and San Antonio that would also

serve Gulf ports at Houston and New Orleans. This required building 800 miles

across Texas, but SP did not have a charter from the State of Texas. The chances

of getting one were poor; the other major railroads in Texas would

fight it vigorously in the Legislature. Hence, Huntington's attention turned to

the GH&SA. The GH&SA had a Texas railroad charter, and due to an

innocuous provision added by Peirce when the charter was amended, the GH&SA was already authorized to

build as necessary to connect with any

Pacific railroad. The tracks to San Antonio covered 200 miles of the

distance between El Paso and Houston, and the GH&SA had rights to operate into downtown

on the Columbia Tap. Peirce had everything Huntington needed except

tracks between San Antonio and El Paso. Huntington and Peirce agreed that SP

would

loan the GH&SA the funds to build between those two points,

and that

Peirce would contract with SP's Southern Development Co. to field construction

forces working east from El Paso. Their work began in June, 1881 under the GH&SA

charter while Peirce's own construction forces built west from San Antonio.

After a bit more than a year and a half, the two railroads met at the Pecos

River on January 12, 1883 where Peirce drove a Silver Spike

signifying completion of a major portion of SP's southern transcontinental rail

line. SP leased the GH&SA for several years before acquiring it.

Huntington's plan for SP's southern transcontinental route across Texas had

ramifications for traffic at Pierce Junction. Huntington needed to transition

all the way across Houston to connect with the rails he was planning to acquire

that ran from Houston to Beaumont and beyond (the

Texas & New Orleans Railroad.) Before work on the San Antonio - El Paso segment

even began, Huntington convinced Peirce to build a GH&SA branch line directly

into Houston. This would eliminate dependence on the Columbia Tap, but more important, the route into Houston could be chosen

for maximum compatibility with the yards north of Buffalo Bayou where SP

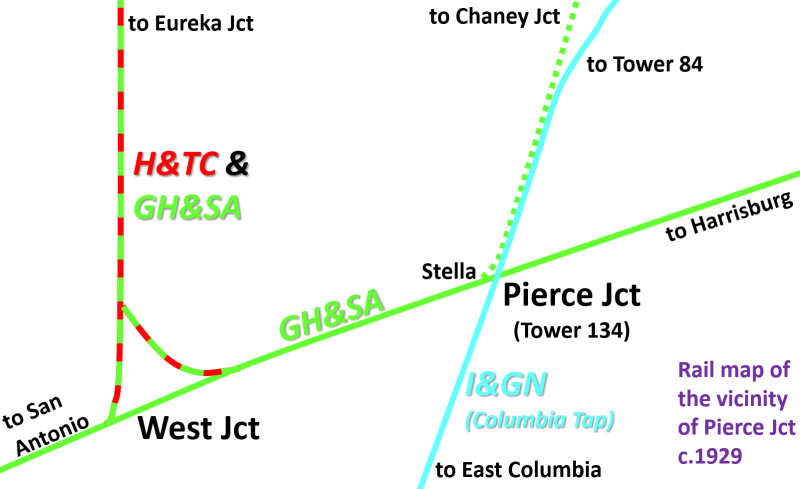

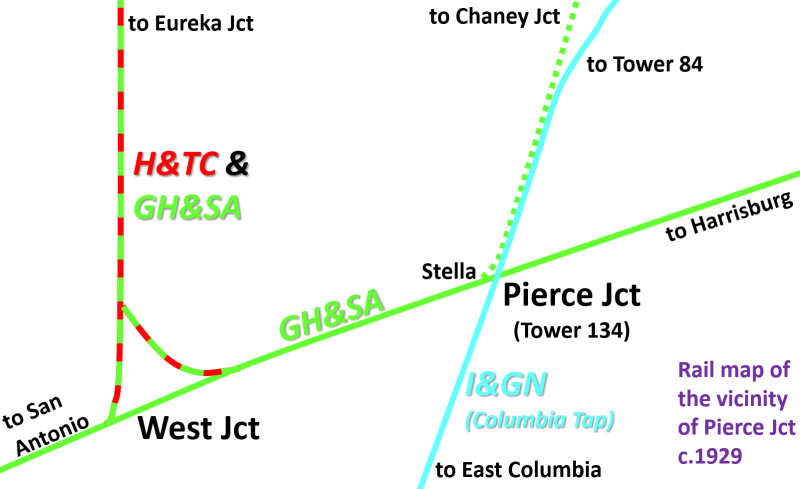

intended to base their southeast Texas operations. Thus, in 1880, the GH&SA

built its own line into Houston from a point immediately west of Pierce Junction

called "Stella". The line proceeded north parallel to the Columbia Tap and

maintained a straight, north-northeast heading for 3.6 miles before turning to a

north-northwest heading and crossing the San Antonio & Aransas Pass (SA&AP) Railroad at

Blodgett Junction. Farther north, the GH&SA crossed

Buffalo Bayou and intersected with the H&TC at grade at "Chaney

Junction". From there, it curved east toward downtown where the GH&SA

was sharing the H&TC passenger depot. SP proceeded to acquire the H&TC

in 1883.

With the GH&SA no longer using the I&GN tracks to reach Houston,

the SP trains that passed through Pierce Junction were mostly those

coming from (or destined to) Harrisburg or Galveston. The massive hurricane of

1900 had wiped out two of the three rail bridges onto Galveston Island, seriously

impacting rail traffic for many years. In 1912, the

Galveston Island Causeway opened, carrying rails shared by several railroads including the GH&SA. As traffic increased to normal levels and

expanded, SP needed a bypass around Houston so that Galveston traffic on the H&TC main line to the

northwest (e.g. Waco, Dallas and Ft. Worth) could avoid transiting through

central Houston. To

satisfy this need, the H&TC built a

9-mile north/south spur about five miles west of downtown to connect the H&TC main line

with the GH&SA main line. The spur ran between

Eureka Junction on the H&TC (a crossing of the Missouri, Kansas & Texas Railroad

interlocked as

Tower 13) and a newly established connection on the

GH&SA known as West Junction.

The GH&SA began

using this new SP route between West Junction and Chaney Junction via Eureka Junction, eliminating

the need for the tracks into Houston from Stella. Except for a short spur at

Chaney Junction, the line into Houston from Stella was abandoned (Almeda Road, from just north

of Holmes Rd. to the intersection with Calumet St., is on the former GH&SA

right-of-way.) On November 17,

1915, SP wrote a short note to the Railroad Commission of Texas (RCT) stating "FYI,

we have removed crossing of the GH&SA Railway Co. and the H&TC Railroad Co. main

line at Chaney Junction and have discontinued operation of Interlocking Plant

#14." In 1918, a second track parallel to the H&TC line between West Junction and

Chaney Junction via Eureka Junction was built to connect with the GH&SA rails

into downtown that had remained intact at Chaney Junction. The traffic through

this corridor warranted an

additional track, and the GH&SA wanted rails into Houston, a claim they had lost

when their line from Stella was abandoned.

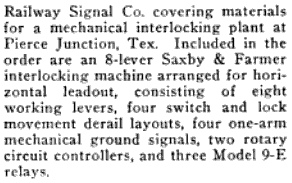

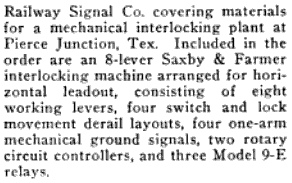

Above: Railway Signaling, May,

1928

Tower 134 was commissioned by RCT at Pierce Junction on March 27, 1929

as an 11-function cabin interlocker (reduced to ten functions shortly

thereafter.) A cabin interlocker was chosen because the Columbia Tap was

significantly less

busy than the GH&SA. I&GN trains would stop at the crossing

for a crewmember to enter the cabin to set the

signals to allow his train to pass; this also signaled trains on the GH&SA that the crossing was occupied. A crewmember would return the

signals to normal (for unrestricted movements on the GH&SA) as

soon as the I&GN train had completely crossed the diamond. The ten functions of

the interlocker would have been four derails, four home signals and two distant

signals. Distant signals weren't needed on the Columbia Tap since all I&GN

trains stopped

to operate the interlocker controls in the cabin.

By the time of the interlocker installation, the

reduction in operations on the Columbia Tap could be attributed to various factors

beyond the loss of GH&SA traffic nearly fifty years earlier. These included

the GC&SF's expansion of service on their shortcut to Galveston from Arcola, a substantial decline in sugarcane and sugar

production around 1923, the rapid loss of population at East Columbia when oil was discovered

in West Columbia in 1918, the development of the port of Freeport after 1912,

and the completion of the St. Louis, Brownsville and Mexico Railway between

Brownsville and the southern outskirts of Houston in 1907.

A salt dome

with an oil and gas field was discovered in the vicinity of Pierce Junction in

1906, but drilling by famed wildcatter Hugh Roy Cullen in 1921 proved that the field was much larger than expected. This

led to an increase in the Pierce Junction population as the oil companies

created housing camps for their employees near the drilling sites. Through 1984,

the field had

produced nearly 90 million barrels of oil.

Robert Martin explains...

"PJ [Pierce

Junction] covered about four square miles roughly defined by Holmes Road on

the north side with Almeda Road running north to south through the center.

Drilling for oil around a salt dome was the reason for development of the

community.

Since Houston was such a long distance away, numerous oil producers built

housing for their employees. There was little infrastructure in this

unincorporated community. The discovery oil well, Taylor #2, was completed on

February 19, 1921 at a depth of 3,490 feet by Gulf Production Company. By

the end of that year over 1.4 million barrels of oil had been produced. By 1938

over 32 million barrels had been produced from 77 wells. ...

Any significant

grocery shopping was done in Houston with the nearest "super market" being on

Main Street and Holman. The only concentration of homes was in the Gulf and

Humble camps with over twenty homes together. The remainder of the homes were

scattered throughout the oil field. At some point the Almeda schools were

consolidated with the Houston schools and the older Almeda children rode busses

with the PJ children."

In 1925, Missouri Pacific

(MP) acquired the I&GN, but both railroads went into a lengthy receivership when

the Great Depression hit in the early 1930s. Coming out of receivership in 1956,

MP fully merged the I&GN and abandoned several unproductive routes including the

southernmost ten miles of the Columbia Tap between East Columbia and Anchor. MP

owned a 4-mile branch line from Angleton to Anchor that was abandoned in 1962

along with nine miles of the Columbia Tap between Anchor and Rosharon. In 1982,

Union Pacific (UP) acquired MP and, five years later, proceeded to abandon 7.5

miles of the Columbia Tap from Rosharon to Hawdon.

Finally, in 1999 UP abandoned three

miles from Hawdon to a point just south of the grade crossing of the Burlington Northern Santa Fe

(BNSF) Railway at Arcola. This was around the time

that UP rehabilitated the Columbia Tap between Pierce Junction and Arcola to be

able to carry coal trains for the Smithers Lake power plant. The Columbia Tap now

terminates immediately south of the BNSF crossing as it makes a sweeping curve

back to the northwest

to reach a switch for a sand and gravel operation while continuing west to Smithers Lake. Although, UP's plan to compete for coal deliveries to Smithers

Lake did not fare well, the Columbia Tap tracks remain intact between Arcola and

Pierce Junction serving various industries. North of Pierce Junction, the tracks

continue 2.5 miles to Holcombe Blvd. and terminate there, serving as an industrial spur but no longer reaching

downtown Houston. North of Holcombe, portions of the right-of-way have been

preserved by the City of Houston to create the

Columbia Tap Rail-Trail. As for the former GH&SA tracks through Pierce Junction, they

remain operational, now owned by UP which acquired them when it merged with SP

in 1996.

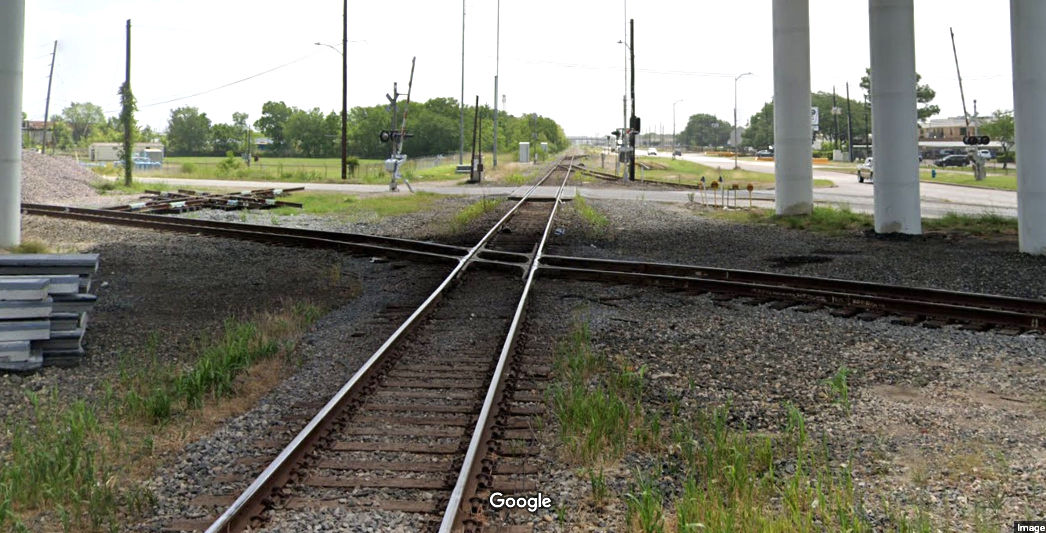

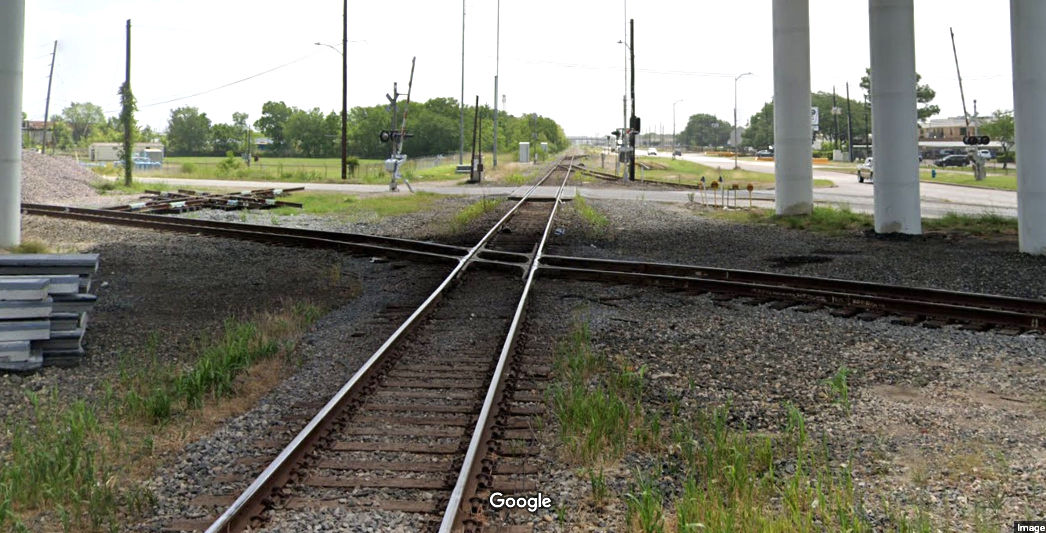

Above: Looking east at Pierce Junction in June, 2022, it appears that construction work

involving a new diamond is underway. Note the southeast quadrant connecting track

partly visible in the distance. Whether this connector has been sustained for

the entire history of Pierce Junction is undetermined, but it certainly existed

at the outset, providing the rail connection to Galveston and Harrisburg needed

by the plantations to the south.

Below: Looking west from the west side of Pierce

Junction in March, 2021, a train approaches Control Point Stella which sits

beneath the overpass for Almeda Road. The street visible in the distance

crossing the two tracks is Knight Rd. which is approximately the location of the

switch at Stella for the GH&SA line to Chaney Junction. According to a 1912

GH&SA timetable, Stella was 0.2 miles west of the I&GN crossing at

Pierce Junction. (Google Street

Views)

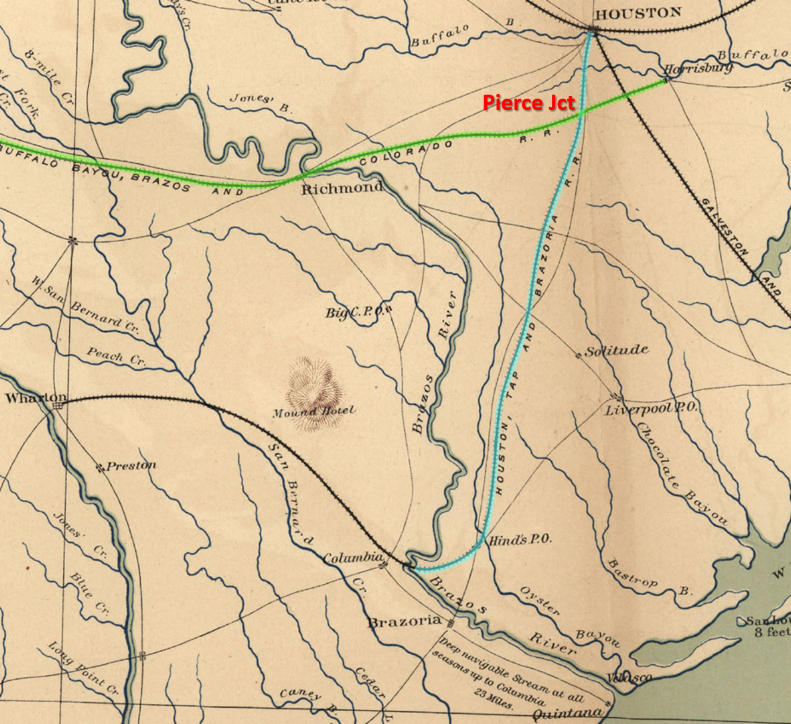

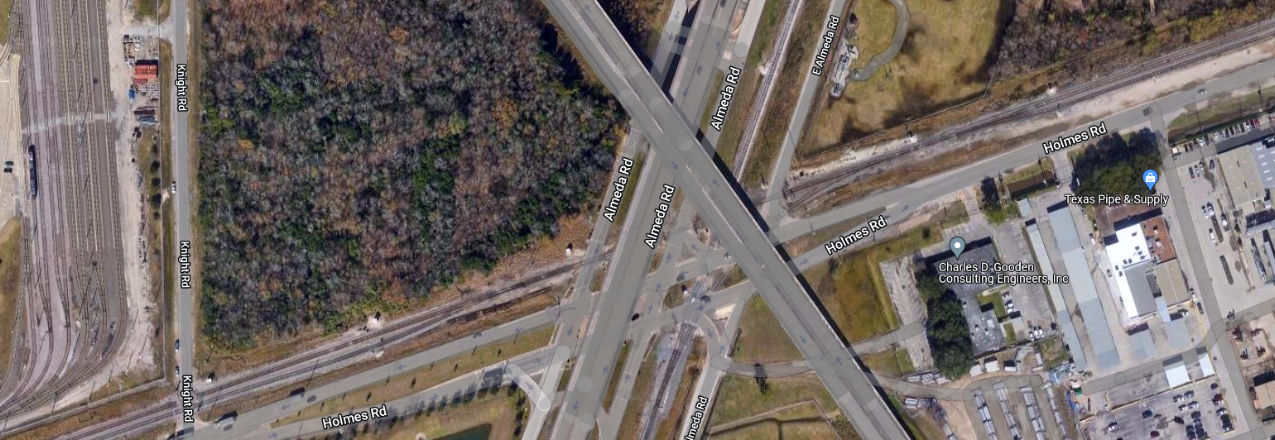

Above: This Google Maps satellite view of Pierce

Junction shows that Holmes Rd. is parallel to the former GH&SA line. The diamond

sits directly beneath the Belfort Ave. overpass which crosses over both Almeda

Rd. and Holmes Rd. The main artery of Almeda Rd. is also elevated over Holmes

Rd. and the tracks, but two frontage roads for Almeda Rd. cross at

grade, as does E. Almeda Rd. Since Holmes Rd. is not elevated, it crosses the

Columbia Tap at grade. The collection of

tracks at left is a maintenance and operations facility for Houston's METRO

Rail. The adjacent street, Knight Rd., marks the location of the switch at

Stella for the tracks to Chaney Junction. [If you use your imagination,

you can see a hint of a tree line that curves north, marking the right-of-way as

it approaches its alignment onto Almeda Rd.]

The timetable shows that at least by 1912 (and probably much earlier), the

route north from Stella was listed as the GH&SA main line and the

track through Pierce Junction to Harrisburg was considered a branch line. Below Left: the Columbia Tap

looking north from the diamond in June, 2022 (Google Street View)

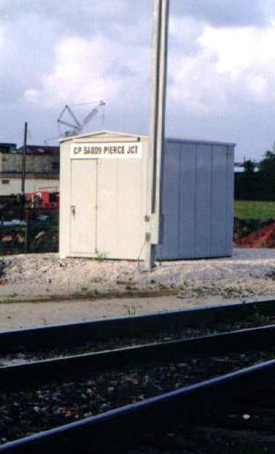

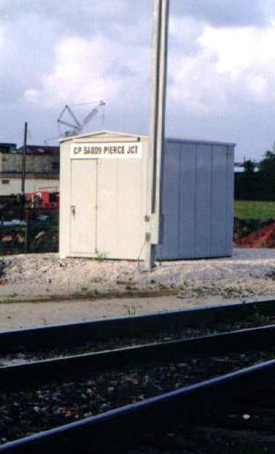

Below Right: This 2005 image

shows that UP had a control point named "Pierce Jct"; it no longer exists.

(Jim King photo)

|

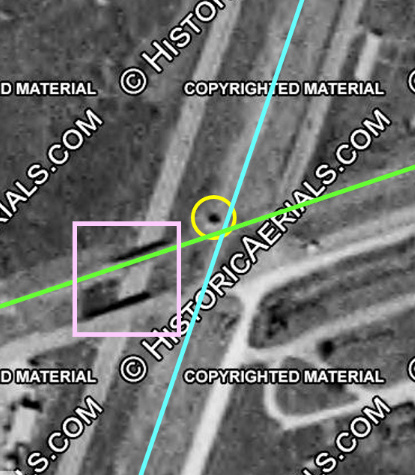

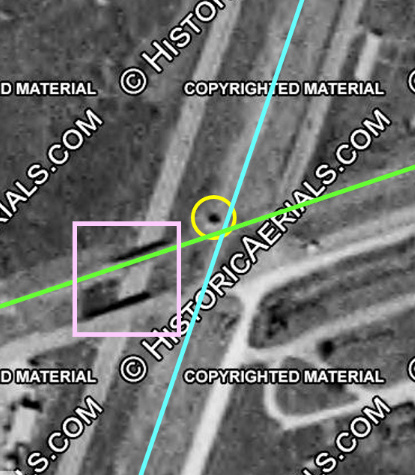

Left:

This 1953 aerial image ((c)historicaerials.com) shows a shadow being cast to the

north (yellow circle), presumably by the interlocker cabin adjacent to

the Pierce Junction diamond. The cabin was north of the SP

(GH&SA) tracks (green) and west of the MP (I&GN) tracks (blue).

Two bridges

casting shadows to the north (pink rectangle) show that in those days, both

Holmes Rd. and the SP tracks went over Almeda

Rd., a situation that is now reversed. Historic aerials show that the

Holmes Rd. bridge survived to at least 1973, and the SP bridge survived

until at least 1983. |

Newspapers

began referencing the GH&SA as "the Peirce Line"; the community

that grew up around Junction appears to have begun using the name "Peirce Junction"

as a result. The

earliest appearance of

"Peirce Junction" in the

Newspapers

began referencing the GH&SA as "the Peirce Line"; the community

that grew up around Junction appears to have begun using the name "Peirce Junction"

as a result. The

earliest appearance of

"Peirce Junction" in the