Texas Railroad History - Tower 23 - Milano

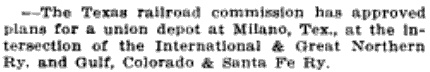

A Crossing of the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe Railway and the

International & Great Northern Railroad

|

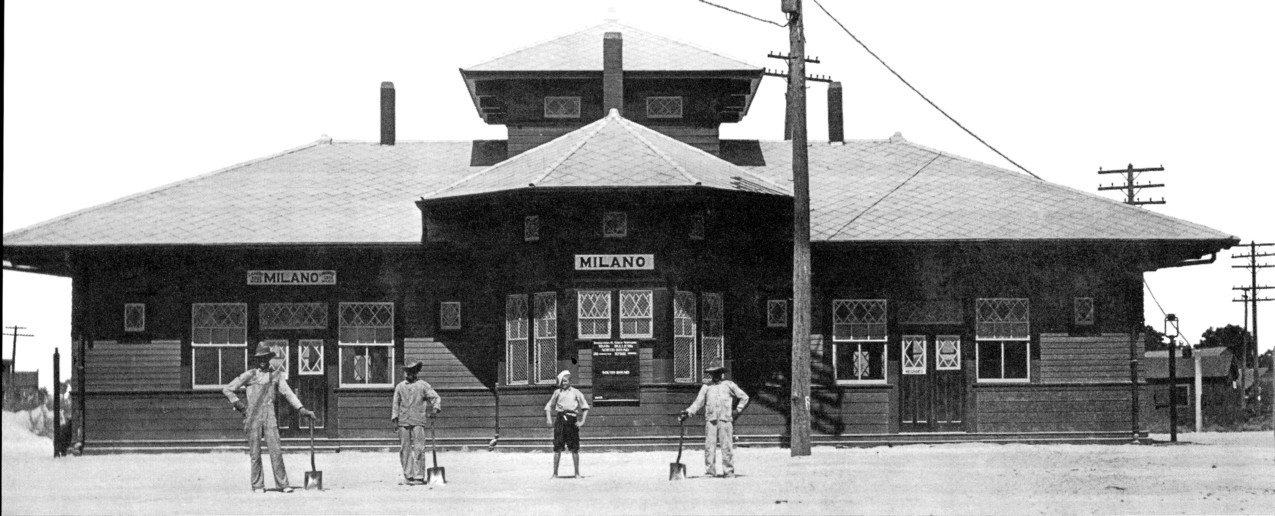

Left: In this

photo, Tower 23 sits diagonally across the diamond from the Union Depot

at Milano where the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe (GC&SF)

Railway had crossed the International & Great

Northern (I&GN) Railroad in 1880 creating a slightly flattened 'X' pattern.

In the south quadrant, Tower 23 was commissioned by the Railroad Commission of Texas (RCT)

on September 1, 1903, the same day Tower 24

at Temple, 44 miles northwest of Milano, was commissioned. Temple was a

regional base for

Santa Fe, which designed and staffed both towers, managed their

construction, and acquired the interlocking plants. Consistent with the

photo, the obtuse angles of the crossing were in the north and south

quadrants where the depot and tower, respectively, were located. |

|

The top photo faces generally northwest along the Santa Fe

tracks toward Temple, with the I&GN tracks crossing behind the tower

(left, southwest toward Rockdale) and in front of Union Depot (right,

northeast toward Hearne.) In the lower photo (left)

the camera faces east toward the

diamond. People are gathered on the depot platform beside a southbound Santa Fe train

arriving from Temple. Both photos show a semaphore signal near the

tower and a connecting track behind the depot with railcars

present.

Special thanks to Ken Stavinoha

for providing these photos, the only two photos of the original Tower 23

found so far. They are undated, but their timeframe can be narrowed by the

architecture of the depot. A new Union Depot (below)

opened in 1914 with Tower 23's functions integrated with the facility. This narrows the date range of these photos to 1903 - 1914. |

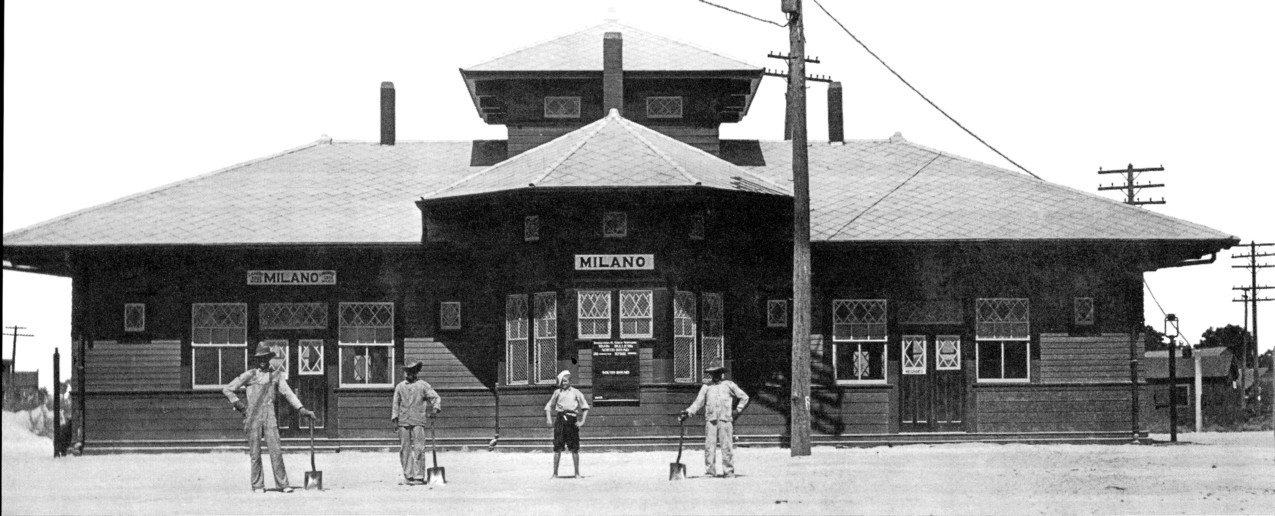

| Above:

This photo of the 1914 Milano Union Depot appears in Robert Pounds' book

Santa Fe Depots, Gulf, Colorado and

Santa Fe Railway (Santa Fe Railway Historical and Modeling

Society, 2012; photo R. L. Crump / Priest Collection.) Tower 23's operations floor and interlocker controls

were located in the tower-like structure atop the depot, which sat in

the west quadrant.

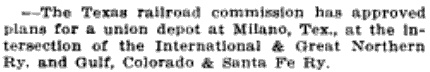

Right: The May 10, 1913 issue

of Railway and Engineering Review

announced RCT's approval of a new union depot at Milano. |

|

Below:

This 1914 plat of the Tower 23 crossing (courtesy Fred M. and Dale M.

Springer Archives and Library, hat tip Craig Ordner and Ken Stavinoha)

shows that the new 1914 depot was built in the west quadrant. The

original Tower 23 is depicted by the small rectangle in the south

quadrant. The 1899 Union Depot (seen in the photos top of page) was in

the north quadrant. A small portion of it was retained for use as a

temporary freight depot until a new one could be built from the salvaged wood.

New connecting tracks were built across the north quadrant space that became

available as the 1899 depot was dismantled.

|

Above: The 'X' pattern of the Milano crossing is readily

apparent in this 1934 aerial image ((c) historicaerials.com.) The Santa Fe line was on a NW / SE

heading and the I&GN line was on a NE / SW heading. The 1914 Union Depot

with integrated Tower 23 function sits in the west quadrant. The Tower 23

building in the south quadrant was razed (at an unknown date) prior to 1934. After the 1914

Union Depot opened, the 1899 Union Depot served as a temporary freight

depot and Railway Express office. It was then dismantled and the

salvaged wood was used to build a new Santa Fe freight depot, very

likely the building visible near the tracks northwest of the depot,

across from the north quadrant where the

1899 depot had been located. |

The International Railroad was chartered in 1870 to

build a line from Texarkana to the southern border via Austin and San Antonio.

The railroad had common investors with the Cairo & Fulton (C&F) Railroad

which was building across Arkansas to connect with the St.

Louis & Iron Mountain Railway at the Missouri border. The idea was to establish a route from St. Louis that

would extend deep into Mexico (hence the International name) by way of

connection to the Mexican National Railway at Laredo. The International's construction commenced in 1871 at two

locations: in a northeast direction from Hearne and

in a southwest direction from Longview. Tracks of the friendly Texas & Pacific

(T&P) Railway were expected to be available to fill the gap between Longview and Texarkana. The

two

International construction crews built simultaneously toward a planned meeting

point: the town of

Palestine. The Hearne crew arrived in July, 1872,

the Longview crew in January, 1873.

With construction underway, the

International's management became interested in the idea of a merger with the

Houston & Great Northern (H&GN) Railroad which had begun building from

Houston toward Palestine in December, 1870. An

agreement was reached to merge the two companies to become the International and

Great Northern Railroad (I&GN) Railroad. The proposed merger required

approval of the Texas Legislature, which would need to pass a new railroad

charter for the I&GN. In the interim, the railroads began operating under a

combined management scheme with Herbert Melville "Hub" Hoxie functioning as

General Superintendent of both railroads. This necessitated moving the

International's headquarters

from Hearne to Houston in December, 1872 so that Hoxie could run both railroads

while awaiting merger approval from the Texas Legislature. In May, 1873, the H&GN's track gang reached Palestine, 151

miles north of Houston, connecting to the International's tracks.

In the summer of 1873, still awaiting a new I&GN railroad charter from the

Legislature, the International resumed construction from Hearne toward Austin. About twenty miles southwest of Hearne, the community of

Milano sprang up on land mostly owned by the International, but the precise

date of the founding is lost to history.

Rockdale, about eight miles beyond Milano, enjoyed newspaper publicity with a sale of town lots on September 3, 1873, but

no evidence of a lot sale at Milano has been found. It may

simply have been a tiny way-station started by settlers who liked the

area and found the railroad willing to sell land (and it most likely was unnamed

until 1874.) Rails reached Rockdale on January 28,

1874, so the International's track-layers probably passed through the area that

would become Milano during the

prior week.

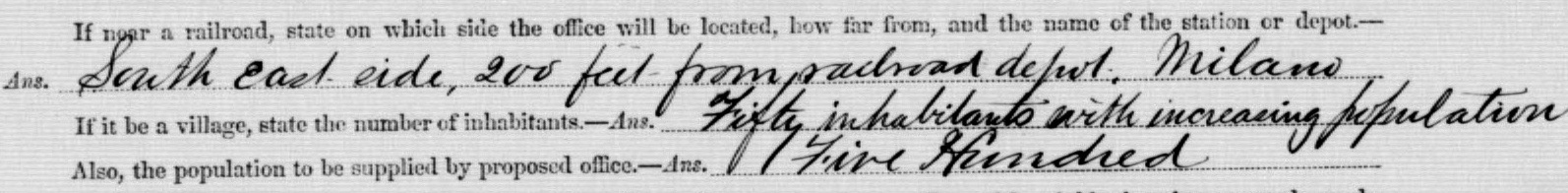

| There is no certainty as to how Milano

got its name. One theory says a proposed name, Milam City, was changed by the Post Office to Milano

because there was already a Milam, Texas (Milano is in Milam County.) Yet,

the name Milano was used

on a May 5, 1874 Post Office application in the same handwriting that

noted the town had "Fifty inhabitants with

increasing population." Evidence that the town was named for

Milano, Italy is also lacking. |

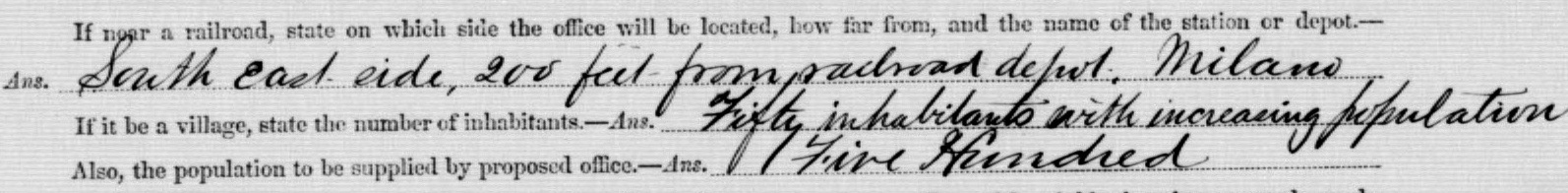

Above: This snippet of

Milano's May 5, 1874 Post Office application (National Archives)

optimistically anticipates 500 residents. With county residents, it

likely served that many at some point, but it is unknown whether Milano's town population ever reached 500. |

Milano's application for a Post Office

in May, 1874 also stated that the railroad passing through the town was

the I&GN, but this was inaccurate. The merger had not been consummated

because the International's request

for construction subsidy bonds to be issued by the State had not been

approved. Claiming

corruption, the Texas Comptroller had refused to countersign and

register the bonds despite the State engineer's report that the work

covered by the bonds was of high quality and met the requirements of the

International's charter. As legal proceedings moved slowly, a lengthy

debate raged statewide. Much ink was spilled as to whether the bond

issuance was in accordance with state law, or instead constituted a

demand by the International for an unconstitutional subsidy. Legislators

are usually responsive to their constituents, and those constituents

didn't care about bond arguments; they

wanted railroads now. This was

certainly true in Austin, which had only a single rail line toward

Houston, and in San

Antonio, which had no rail lines at all.

Right: The

Galveston Daily News

of March 26, 1875 reported that a compromise had been reached. The

merger was approved shortly thereafter by the Legislature with the

passing of a railroad charter bill for the I&GN that was signed into law

by Gov. Richard Coke.

Construction had been halted at

Rockdale while politicians and journalists debated the International's

bonds. It finally resumed on May 22, 1876, a year after the compromise

had been accepted. Rails reached Austin on December 16, 1876, but the

work stretched the I&GN's finances to the breaking point. On April 1,

1878, the company was forced into receivership and then sold at

foreclosure on November 1, 1879. The buyers formed a new I&GN company

under the original charter and management team. Construction was

restarted from Austin toward San Antonio on May 31, 1880 and the tracks

reached San Antonio on February 16, 1881. |

|

In May, 1874, the C&F and the St. Louis & Iron Mountain

had been reorganized and merged to create the St. Louis, Iron Mountain & Southern

(SLIM&S) Railway. The SLIM&S would eventually become part of rail baron

Jay Gould's Missouri Pacific (MP) Railroad. MP was the railroad through

which Gould planned to extend his rail

empire into Texas, but he needed the SLIM&S for a connection back to St. Louis

where MP was based. Gould recognized the value of the I&GN's planned

track network which would, via Longview, connect the SLIM&S at Texarkana with Mexico

and with three of Texas' most important cities: Houston, Austin and San Antonio.

Gould also wanted to extend the I&GN from Houston into Galveston,

Texas' major port and largest city. With this foresight, Gould developed a long term plan to capture control

of the I&GN, which was quickly becoming Texas' largest railroad.

|

Gould's plan involved

gaining leverage over the I&GN by controlling its access to Midwest markets. To

accomplish this, Gould needed both the T&P and the Missouri, Kansas & Texas (MK&T, "Katy") Railway

to be added to his empire. The Katy had bridged the Red River from Oklahoma into

Denison in 1872, providing a Texas gateway to

Oklahoma, Kansas and Missouri. Gould took over the Katy simply by being elected its

President in December, 1879. Although he had virtually no ownership in

Katy stock (the stock was far too diluted to attempt a financial takeover) Gould had planted many allies into its management ranks over a period

of several years, and they successfully engineered his election. Gould

inaugurated his tenure as Katy President by leasing the Katy to MP in late 1880.

The lease arrangement used accounting methods to siphon Katy profits into MP

where Gould could benefit from his stock ownership. This was to the severe detriment of Katy

stockholders, who eventually held him accountable. Capturing the T&P was easier;

Gould took financial control in April, 1881 by personally funding its

construction between Fort Worth and El Paso.

Gould's control of the

Texarkana (SLIM&S) and Denison (Katy) rail gateways to the Midwest gave him leverage over the

I&GN. [Other gateways to the north through Fort

Worth and Paris did not yet exist.]

Hemmed in by Gould railroads, the I&GN agreed to a swap for Katy stock

in June, 1881. This resulted in the Katy owning the

I&GN and Gould becoming I&GN President. The Katy was based in Kansas and

lacked a Texas railroad charter. The Legislature had (in 1870) simply granted the Katy permission to bridge the Red River into Texas under its

Kansas railroad charter. Fearing a lawsuit by the State for a potential

violation of Texas' restrictive railroad ownership laws, Gould did not

want the Katy's ownership of the I&GN known publicly. Gould finessed the

financial details, going so far as to place all of the I&GN stock

certificates secretly with a trusted party in Fort Worth so he could claim (if

forced to do so) that the I&GN's true owner was a resident of Texas. To

extract profits from the I&GN, Gould leased it to the Katy, ensuring

that money

flowed into MP (and Gould's pocket) through MP's lease of the

Katy.

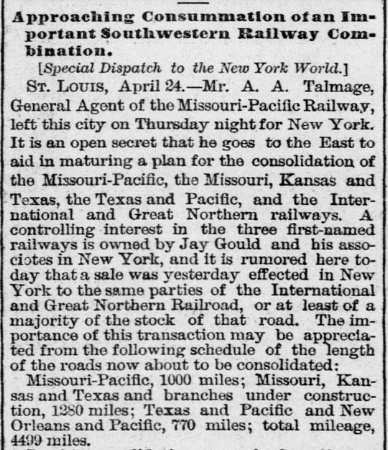

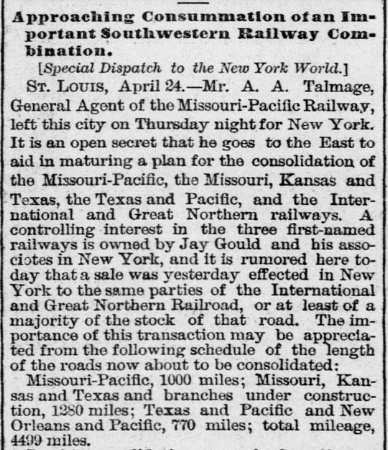

Left: A full month

before

his acquisition of the I&GN, the

Galveston Daily News

of April 30, 1881 reported speculation by New York papers that

discussions were being held to consolidate Gould's MP and Texas

railroads, including the I&GN. The article was incorrect regarding

Gould's ownership of the Katy. Gould

was Katy President, but he lacked financial control, a fact he would

experience firsthand when Katy's stockholders fired him in 1888.

Yet, the Katy was eventually forced by the Legislature to sell the

I&GN (in 1892) and Gould was the only bidder, attaining his original goal of

owning the I&GN. |

In the early 1880s, Gould initiated an ambitious plan

to build MP tracks from Denison southward through

Fort Worth and Waco,

eventually turning east toward Houston. This was

blatantly illegal since both MP and the Katy lacked Texas railroad charters, but

his efforts remained unchallenged for several years -- "everyone wanted

railroads." MP received the publicity and had its name on depots while the Katy

held the actual title to new

MP track construction. Gould did not seek his own Texas railroad charter; it

would have been opposed vigorously by all Texas railroads and their numerous

allies in the Legislature. Instead, Gould's theory of getting around the charter

requirement began with the fact that the Katy had a legal presence

in Texas (at Denison.) Gould claimed his MP / Katy construction southward toward Mexico was

consistent with the requirements of the Katy's Kansas charter (which described a

route to the Rio Grande) and that the Kansas charter arguably had

been "accepted" by the Legislature. This rationale ultimately held no sway; MP was completely evicted from Texas when the Katy lease was broken

by the Texas Supreme Court in 1890. Prior to that time however, the MP / Katy

construction enterprise marched southward aggressively.

Gould's takeover

of the I&GN gave him tracks in Houston that extended northward to the Texarkana

gateway via the T&P's line out of Longview. As Gould was planning to reach Houston

with Katy tracks in a couple of years, he personally bought the Galveston, Houston and Henderson (GH&H)

Railroad on August 1, 1882 which ran between Galveston and Houston over the

original rail bridge off Galveston Island. Although Gould easily could have moved the

GH&H into the I&GN, he instead sold it to the Katy and the Katy promptly leased

it to the I&GN. This gave the I&GN access to

Galveston and would facilitate Katy access whenever its tracks reached Houston.

By the time Gould acquired the GH&H, it no longer had the only rail bridge off

Galveston Island. The Gulf,

Colorado & Santa Fe (GC&SF) Railway had initiated construction out of

Galveston in 1875, ostensibly headed for Colorado. In

reality, the rail line was mostly intended to provide a route -- any route

-- into Galveston that did not go through Houston. Galveston-bound freight was

sometimes (for both credible and nefarious reasons) diverted away from the GH&H and

placed on barges to be sent down Buffalo Bayou directly to ships in Galveston's

harbor. This was Houston's method of fighting against dock policies of the

Galveston Wharf Co. that were heavily biased in favor of Galveston shippers.

Starting with a new bridge over Galveston Bay,

the GC&SF's construction went west-northwest, remaining well south of Houston.

It reached

Arcola in 1877 and crossed the Brazos River into Richmond in 1879.

Unable to meet its obligations, the GC&SF went through foreclosure and was purchased

by its Treasurer, George Sealy, who reorganized the company under its original

charter. Construction resumed in early 1880 at

Rosenberg heading northwest toward Brenham,

which it reached in April. After a brief pause, construction continued, reaching Milano (November) and

Cameron

(December) later that year. Santa Fe commenced service as far as Belton on March 18,

1881, eight miles beyond the major construction camp it had established at Temple

Junction, named for the railroad's chief engineer, Bernard Temple. From

Temple (the Post Office dropped Junction) Santa Fe

built 128 miles

north to

Fort Worth, the line opening for service on December 20,

1881.

Main lines radiated out from Temple in three directions: to Galveston, to Fort

Worth, and to the northwest through Belton, Lampasas (1882), Brownwood

(1885) and San Angelo (1888.) Temple became a major operations and maintenance center while the

company remained headquartered in Galveston. The GC&SF was acquired by the

much larger Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe (AT&SF) Railway in 1887, but continued to

operate under its own name.

Santa Fe's 1880 construction from Brenham to

Temple passed about a mile and a half east of the settlement of Milano and

crossed the I&GN at a site known as Milano Junction to which the town migrated

over the years. The former settlement became known as Old Milano; it

was soon a ghost town and disappeared. On June 15, 1885, the

Postmaster at Milano submitted an updated application to relocate the Milano

Post Office to the junction, noting that the new distance to Rockdale was now ten

miles instead of nine miles. Although it

appears from Census data that the population of Milano has never reached 500

persons, the town gained outsized publicity in the early years because of its

railroad junction. The I&GN / Santa Fe crossing developed into an important

transfer point for passengers because the two railroads' service areas were

highly complimentary. It did not take long for the railroads to begin making

this point to the public.

|

Left: Even as Santa Fe's tracks

had yet to reach Belton, stray one-liners began to appear in newspaper columns proclaiming Milano Junction as the new time-saver

for travel between Austin and Galveston, Texas' capital and Texas'

largest city, respectively. (Austin Weekly Democratic Statesman,

February 3, 1881) |

The above claim was simple: an Austin - Milano (I&GN)

and Milano - Galveston (Santa Fe) itinerary was faster than the

competing route on the Houston & Texas Central (H&TC) Railway,

which had a branch to Austin from the H&TC main line at Hempstead, northwest of

Houston. Taking the H&TC eastward out of Austin required a change of trains

at Hempstead followed by a change of railroads at Houston since the H&TC did not serve Galveston.

The above advertisement was published two years before Southern

Pacific (SP) acquired the

H&TC. SP was able to obtain trackage rights on the GH&H

into Galveston, but even then, the need to change trains twice out of

Austin would have remained the basic scenario for SP's route.

Santa Fe had the most to gain by advertising the

Milano Route. Though it was one of the major railroads in Texas, it did not

serve Austin, which generated passenger traffic greater than its size would

justify simply by being the state capital. Santa Fe did not serve San Antonio,

the second largest city in the state, nor did it reach the southern border for

connections into Mexico. The Milano Route

was important to Santa Fe markets north and west of Temple simply because the

I&GN route to Austin, San Antonio and Laredo was highly complementary to Santa Fe's network.

| Right: The

Galveston Daily News of June 12, 1881 reported the

construction of a "magnificent hotel" at Milano "immediately in the

junction." There are no Sanborn Fire Insurance maps of Milano to prove

the hotel was actually completed, but it was certainly an idea premised

on the growing success of the Milano Route. And this was six months

before Santa Fe's tracks reached Fort Worth. |

|

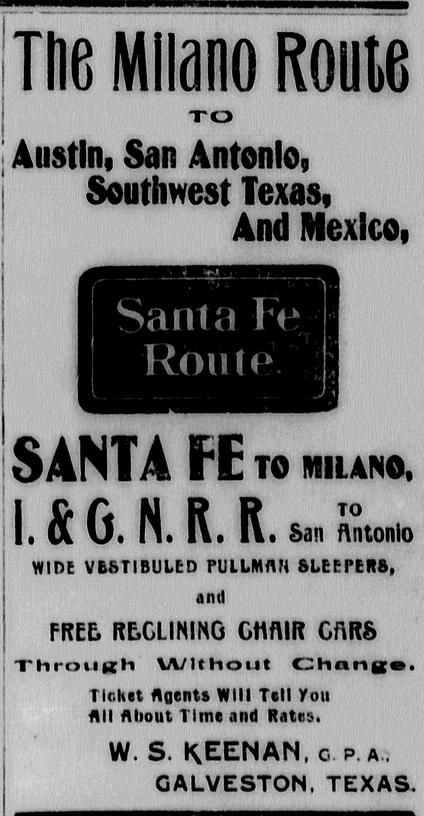

In the 1898 - 1902 timeframe, Santa Fe aggressively

marketed the Milano Route with a newspaper campaign. Countless

newspapers across the state carried advertisements on a daily or weekly basis.

The ads uniformly listed W. S. Keenan, General Passenger Agent for Santa Fe in

Galveston, as the sponsor / contact. Most of the time, the I&GN was also

mentioned since it was a key component of the Milano Route.

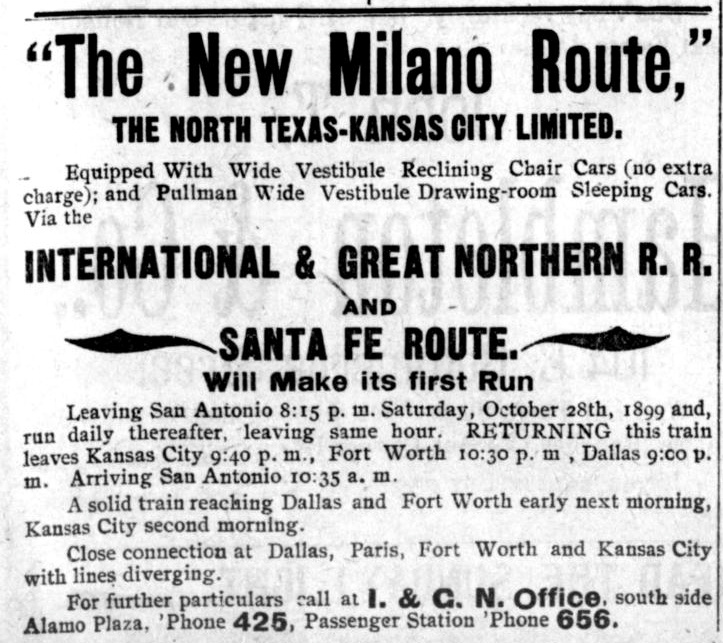

Above Left-to-Right:

Milano Route ad (Chino Chapa collection);

Caldwell News-Chronicle, November 24, 1899;

Goldthwaite Eagle, April 7, 1900;

Alpine Avalanche, January 17, 1902.

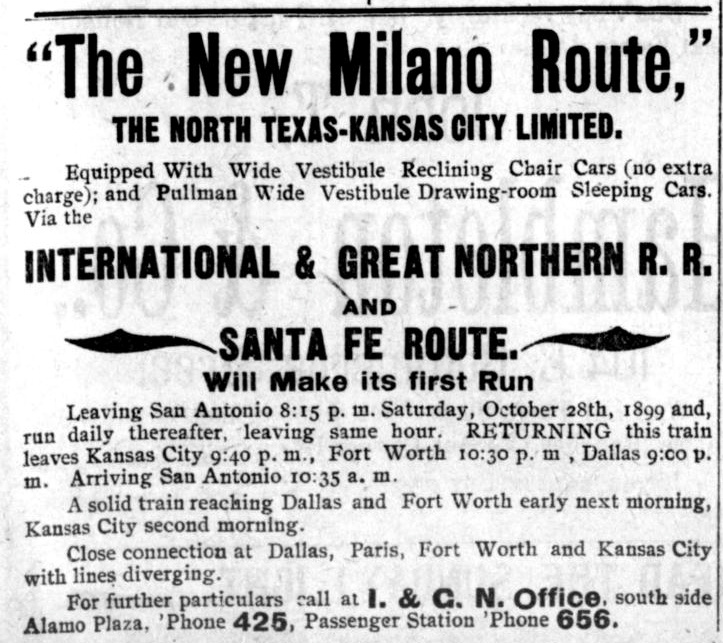

Below Left: The

San Antonio Daily Light of October 28, 1899

announced the start of single-train passenger service from San Antonio to Kansas

City via the "New Milano Route". The only "new" part was not needing to change

trains at Milano. Below Right:

Within a few months (San Antonio Daily Light,

April 24, 1900), the Milano Route was being advertised with

"Through Pullman Sleepers" and "No Change of Cars; No Transfers"

even though this had always been a feature for at least some schedules as evidenced by the ads above.

Single-train service likely persisted in

some markets (Kansas City) on particular schedules. St. Louis was now an

advertised service point which Santa Fe reached by way

of a Temple - Cleburne -

Dallas - Paris routing. At Paris, Santa Fe

connected with the St. Louis & San Francisco ("Frisco") Railway which in

1888 had opened a line

through eastern Oklahoma and northwest Arkansas to Frisco's main rail network at

Monett, Missouri. The Frisco and Santa Fe also collaborated on single-train

Dallas - St. Louis service accessible at Dallas by Milano Route passengers. The I&GN,

however, would have preferred

that San Antonio - St. Louis passengers take a San Antonio - Longview -

Texarkana - St. Louis routing (Gould railroads all the way) which was likely single-train service on at least a few schedules.

|

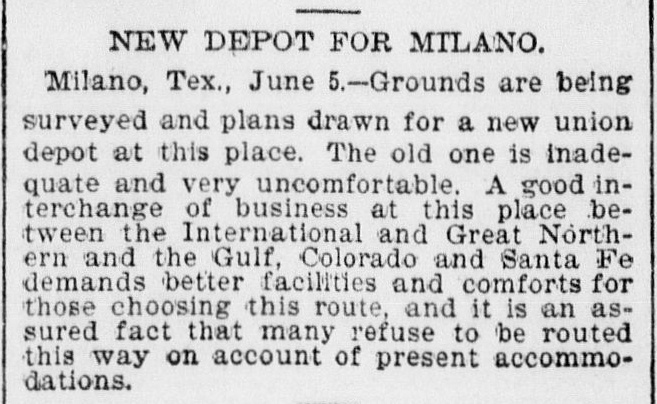

Left:

Galveston Daily News, June 6,

1895

The depot arrangement at Milano in the early

years is undetermined. The I&GN may have built a depot in the 1870s at what ultimately became Old Milano. The reference to Milano Junction

in advertisements for Austin - Galveston service a mere three months after

Santa Fe built through Milano implies that the railroads collaborated on an early

joint passenger station, or perhaps the I&GN began stopping at a Santa Fe depot

near the crossing. It is doubtful, however, that any early depot

could have been designed to anticipate Milano's rapid growth in transit passengers.

By the mid 1890s, the facilities at Milano had become

unsuitable for the volume of traffic being generated by the Milano

Route, so much so that passengers had begun to

"refuse to be routed" through Milano due to "present

accommodations". This no doubt caused alarm to both railroads,

and a new Milano Union Depot was planned and built, opening in 1899. This is undoubtedly the

depot that appears in the photos at top of page. Pounds' book

describes it as a "1899 22'x112' "L" frame

board & batten passenger depot" but the early photos show

the shape was more complex. Also incorrect (as the photos show) is the

book's assertion that an interlocking tower was built into the 1899 Union

Depot (it was the 1914 depot.) |

|

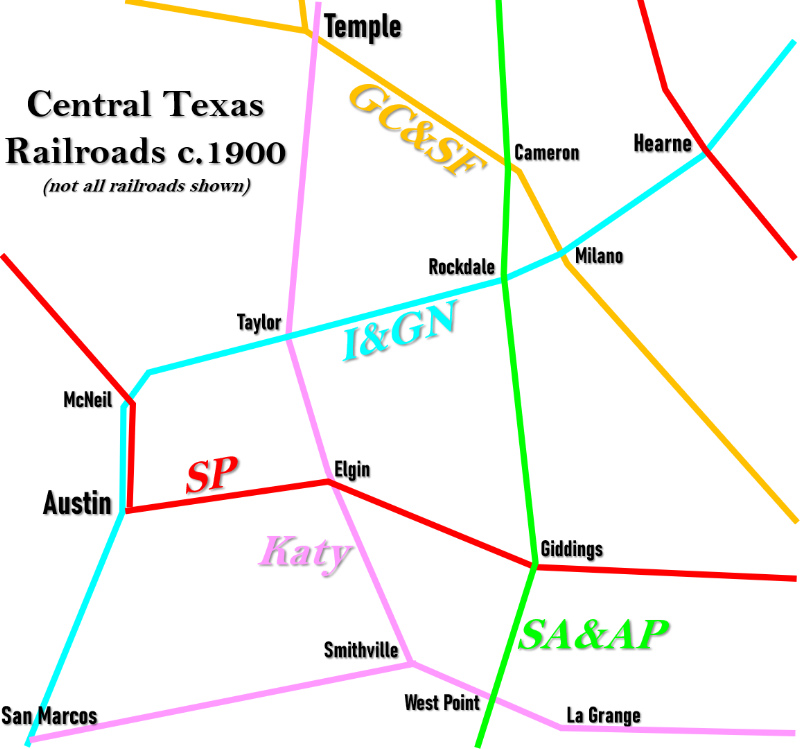

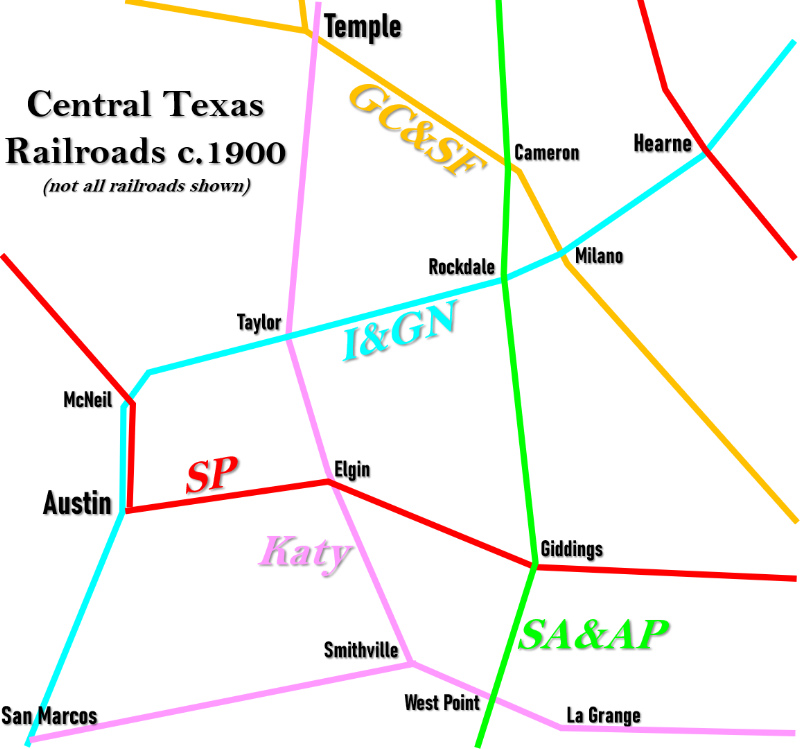

Left: This area map of rail lines c.1900 shows

that railroads in Central Texas formed a loose grid of

north / south and east / west railroads (and some that did both!) The first of

these rail lines to be built was the Houston & Texas Central (H&TC) Railway's

route into Austin in 1871. The H&TC became owned by Southern Pacific (SP) in

1883. To the east, the H&TC's tracks connected to its main line running north out of

Houston through Hearne to Dallas

and

Denison.

Another railroad closely affiliated with

SP, the San Antonio & Aransas Pass

(SA&AP) Railway, had a track network in south Texas serving San Antonio and

Corpus Christi. SA&AP opened a northward extension

from Yoakum to Waco in 1891, but by then, the

railroad was bankrupt. SP acquired a significant SA&AP stockholding and assisted

the SA&AP in emerging from receivership in 1892 by agreeing to back SA&AP

construction bonds. The two railroads worked together closely, but SP was not

permitted to acquire the SA&AP. They competed in several markets, hence

SP control would violate Texas' railroad competition laws. An RCT

investigation in 1903 forced SP to admit

to unlawful control of the SA&AP, and they were assessed a severe financial

sanction from RCT as a consequence.

In 1914, SP opened a new line between

Hearne and Giddings to facilitate a bypass of Houston for west coast traffic to /

from north Texas. The SA&AP tracks from Giddings through

West Point to

Flatonia formed the southern part of the bypass. SP

acquired the SA&AP legally in 1925.

SP's long

association with the SA&AP (both legal and illegal) may have contributed

to RCT's decision not to require an interlocker at Giddings. All of the

other crossings on this map involving two different

railroads were ultimately interlocked

with numbered towers commissioned by RCT, specifically:

Tower 15 (Hearne), Tower 23 (Milano), Tower

24 (Temple), Tower 34 (Taylor),

Tower 52 (Cameron),

Tower 54 (Rockdale),

Tower 91 (West Point),

Tower 100 (Elgin),

Tower 132 (McNeil), Tower 205 (Austin)

and Tower 206 (San Marcos). |

A new state law in 1901 gave RCT authority over all

crossings of two or more railroads, tasking it to address crossing safety while

improving railroad operations. By existing law, all trains had to stop before

crossing another railroad at grade, often creating unnecessary delay and

wasting train momentum (and thus fuel and water) since most

of the time, the crossing was not occupied by another train. RCT soon began

mandating interlocking plants with appropriate signals and derails at

major crossings. An interlocker might have prevented a crash at Milano on Christmas Day, 1898.

Right: Railway Gazette

January 18, 1899 |

|

A special order issued by RCT on June 5, 1902 required

the I&GN and GC&SF to interlock their crossing at Milano by June 30, 1903.

Santa Fe took the lead in managing the construction project, resulting in a

building that closely resembled Tower 24 at Temple, which opened the same day,

September 1, 1903.

Milano's new interlocking was commissioned for operation by RCT as Tower 23 with a 19-function electrical interlocking plant built by the

Taylor Signal Company. The functions were controlled using eighteen levers

operated by personnel in the upper floor of the two-story tower. The plant and

associated electronics were housed in the lower floor of the tower. Since a

typical minimum interlocker required twelve functions (a home signal, distant

signal and derail in each of the four directions) Tower 23's higher function

count points to the presence of the exchange track behind the depot, and there may

also have been connectors in other quadrants by 1903.

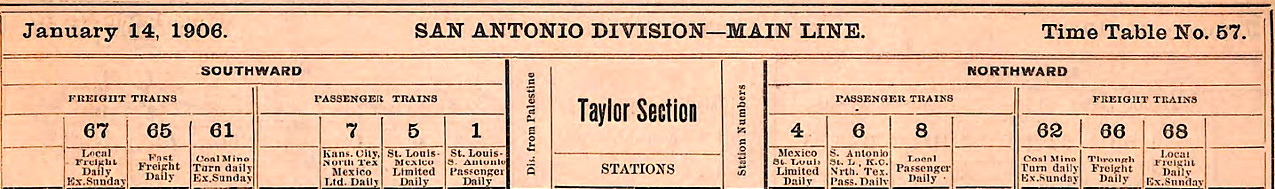

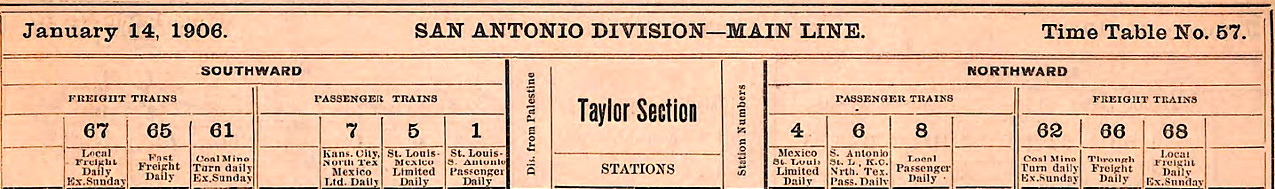

Above: An Employee Timetable (ETT) issued by the I&GN on

January 14, 1906 provides an interesting snapshot of the I&GN's passenger

service through Milano. By this date, the I&GN was no longer showing

single-train service to / from Kansas City via Milano. All I&GN trains through

Milano stayed on I&GN rails in both directions. The ETT shows three passenger

trains and three freight trains in each direction. The passenger train markets

were St. Louis - Mexico, St. Louis - San Antonio, and Kansas City / North Texas -

Mexico. The northern endpoint on I&GN rails for the Kansas City train was at Hearne, the implication being

that the northern segment for this market was handled by the H&TC (SP) from

Hearne to Denison, and by the Katy from Denison to Kansas City. This routing competed

with Santa Fe's Kansas City service through Temple, Fort Worth and

Oklahoma City. Below: In the 1908

Official Guide of the Railways, Santa Fe

published a full page dedicated to its Chicago - Mexico City service schedule.

The giant title block at the top of the page listed Milano among the vastly

larger and more famous cities of Chicago, Mexico City, San Antonio and Laredo.

This was a recognition of the success Santa Fe had achieved in promoting the

Milano Route for Midwest service to / from Austin, San Antonio, Laredo and Mexico.

The Mexico City route was not single-train service -- Santa Fe's southbound

train continued to Houston and Galveston but transferred sleepers and other

passenger cars to the I&GN. Milano was tiny, but it was enjoying national fame thanks

to the railroads; travelers to and from Texas knew about Milano.

Within a decade of opening the 1899 Milano Union Depot, the facility was already beginning to show signs of strain due to the

high numbers of passengers transiting the Milano Route. By 1913, the

citizens of Milano were pushing for an even larger and more modern depot, and

the railroads had agreed that yet another new union depot would be required. At

a hearing held by RCT in February, 1913, the railroads submitted their plans for

a new union depot that would include an integrated tower to replace Tower 23.

The Tower 23 structure was less than ten years old, and it is unknown whether

specific problems with the building motivated the change. It's possible that the

railroads were taking a long-term view of the interlocking from an operations

and maintenance (O&M) efficiency standpoint. At minimum, it was cheaper to

maintain one building than two. Also, in a combined

facility, a single telegraph operator could easily serve depot operations and

the general public while handling train-related communications for the

tower. Santa Fe had already built

depots with integrated interlocking towers in 1904 at Morgan

and McGregor. Both had electronic plants as did Tower 23, which Santa Fe preferred. It was much less

expensive to re-engineer an electric interlocking compared to a mechanical

interlocking because new wiring was inexpensive and could be connected to

existing signals, switches and derails with ease.

|

Left Top: A report in the

San Antonio

Express of February 18, 1913 stated that the railroads' plans

for a new union depot at Milano were ordered by RCT to be submitted "to

the citizens of that place" for approval. Other news stories suggest

that it was the citizens of Milano that had initially petitioned RCT to

order the railroads to build a new union depot. However it transpired,

the railroads proceeded to develop architectural plans

which were the subject of the hearing.

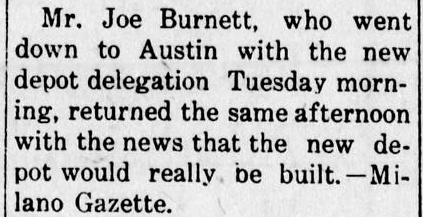

Left Bottom:

The

Rockdale Reporter and Messenger

of Thursday, February 20, 1913, quoted good news reported by the

Milano Gazette. That it would

"really" be built suggests that doubt had been circulating among the

citizens as to whether their push for a new depot would be successful.

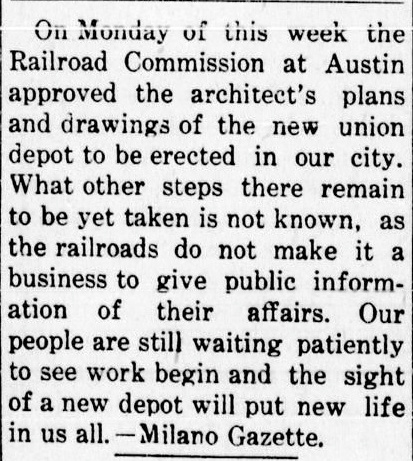

Right:

The

Rockdale Reporter and Messenger of May

15, 1913 quoted a Milano Gazette

report that the plans for the new union depot had been approved by RCT,

presumably with concurrence by Milano's citizens. |

|

Above Left and Center: The

Cameron Herald of July 30, 1914

quoted the Milano Gazette when

it announced that the new Milano Union Depot would likely open a couple of days

later on August 1. The report also states that the old depot would be repurposed as

a temporary freight depot and a Railway Express office. Above Right:

Robert Pounds' book includes this 1930 photo of the back of the 1914 Union Depot.

From the 1934 aerial image and the details evident from the photo (top of page) showing a

straight-on view from the front, it is apparent that the depot had a "+" shape.

The depot appears to have been repainted using

Santa Fe's common yellow with green trim paint scheme, retaining the white window frames. The original primary color was mineral brown.

| Right:

A new freight depot was built from the salvaged wood of the 1899 Union

Depot. The article references "truck shipping sheds." This

was a reference to "truck farms" from which table-ready vegetables were

harvested and brought to the depot by truck. This was big business for

Milano area farmers. (Rockdale

Reporter and Messenger, November 16, 1916) |

|

|

Left:

1915 Katy track chart of Milano (Ed Chambers collection)

After the Texas Supreme Court broke MP's lease of the Katy, the Texas

Legislature re-chartered the Katy in 1891, authorizing a subsidiary

headquartered in state (at Denison) as required by

Texas' railroad laws. By 1915, its Chief Engineer's office had relocated

to Dallas and undertaken a

project to draw track charts for junctions throughout Texas, even those

like Milano that did not involve the Katy. This chart shows that by 1915, exchange

tracks were present in all quadrants except the east quadrant, and there

were several sidings. The 1914 Union Station

is depicted

in the west quadrant. The partly legible writing in the upper right corner says

"To

Valley J'ct'n & Palestine." Valley Junction

was near Hearne where the I&GN main line crossed another I&GN line that opened between Fort Worth and Spring (near

Houston) in 1902. This line plus the original

Palestine - Houston line explains generally why there was no east connector at

Milano. From points east of Milano, the I&GN had its own routes to

Houston / Galveston; it did not need to interchange with Santa Fe.

While Milano's west connector is known to have handled single-train

service between San Antonio and Kansas City, it was undoubtedly used

frequently for railcar interchange, both passenger cars (sleepers, etc.)

and freight. The other two connectors were for freight operations,

particularly the south quadrant which led to the Port of Galveston and

was used for exports from points west of Milano. Locally, Milano became

a major shipping point for vegetables from area truck farms. Quoting the

Milano Gazette, the

Rockdale Reporter and Messenger of June

6, 1912 discussed how northbound and eastbound trains at Milano were being

"greatly delayed" by the extra time needed to load "immense shipments" of

crops. In addition to the usual vegetables, "...berries and fruits of

all kinds are now being shipped." |

|

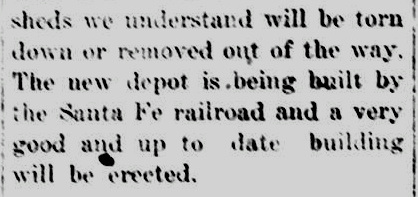

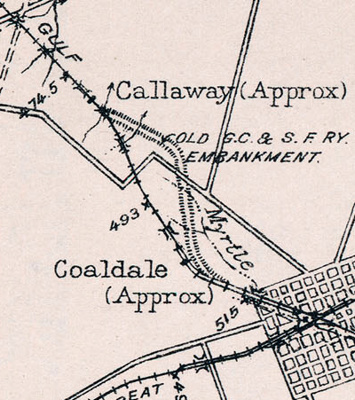

Left:

The "Old G. C. & S. F. Ry. Embankment" on this 1919 topographic map of

the northwest outskirts of Milano shows that by then, Santa Fe had

rebuilt the grade to straighten the tracks, replacing two sharp curves

over the span of 1.2 miles. The date this reconstruction occurred has

not been determined. The line change improved arrival and departure

schedules for Santa Fe trains.

Right: This 1960

aerial image ((c) historicaerials.com) clearly shows the former grade at

least four decades after the line change. |

|

By the

end of 1923, Tower 23's function count had increased to 22. RCT's Annual

Report issued at the end of 1928 reported 20 functions for Tower 23, and the function

count remained at that number through the end of 1930 (after which RCT

stopped reporting interlocker parameters annually.) RCT documentation

from 1916 confirms, as expected, that Santa Fe was responsible for staffing Tower

23. The recurring O&M expenses were shared

between Santa Fe and the I&GN, but the split has not been

determined (likely close to 50/50.) Because the crossing existed long

before the 1901 law that gave RCT authority over crossing safety, the railroads

would have been required to split the capital expense for Tower 23 evenly.

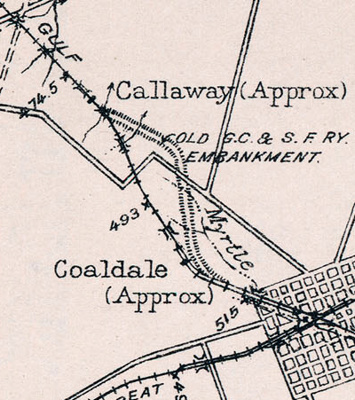

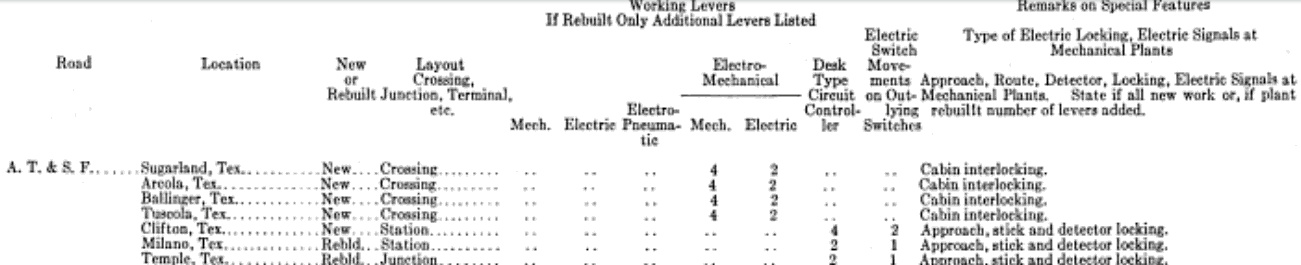

Above: This excerpt from a

table published in the January, 1926 edition of

Railway Signaling and Communications reveals that at least a portion

of the Milano interlocking was rebuilt in 1925. The interlocking layout was

designated as "Station" type since the tower was part of Milano Union Depot. How

the changes incorporated by this rebuild related to the overall function of the

plant is undetermined. Into the 1920s, RCT had kept a tight reign on interlocker

changes, but the Federal Transportation Act of 1920 gave wide authority to the

Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to manage all aspects of railroading (since

all major railroads operated interstate.) Railroads began to seek ICC approval

for most interlocking changes because they were within the ICC's jurisdiction. RCT became dependent upon the railroads for updates to the

parameters of each interlocking plant, and this occurred annually near the end

of the year. It was not uncommon to find that a railroad's office that

handled

this reporting to RCT did not always stay up to date on changed information at all of

the company's interlocked crossings nor maintain accurate records thereof. There's a

chance that this 1925 rebuild accounted

for the reduction to 20 functions reported in 1928.

|

Far Left: An

update to the Milano interlocking was reported in the June, 1941 edition

of Railway Signaling. The

changes included removal of two main track derails "to conform to ...

recommended practice." Studies had shown that main track derails caused

more problems than they prevented, and RCT stopped requiring them in

1930.

Near Left: The

January, 1959 issue of Railway Signaling

and Communications contained this table showing that Milano's

interlocking had been rebuilt in 1958. Four of the six home signals

would have been for the main tracks. The other two probably related to

the west connector. |

Jay Gould died in 1892 and his son George became

President of the I&GN and the T&P. Ten years later, the I&GN opened the

aforementioned route between Fort Worth and Spring through Valley Junction. Fort

Worth had become a major gateway for freight from the Plains and Mountain West

states heading for export at Galveston. The I&GN wanted to compete with

Santa Fe and SP, each of which already provided service in the Fort Worth -

Galveston market. The I&GN used rapid construction techniques for the new line

which proved to be poorly executed resulting

in a frequency of major accidents that rose to unacceptable levels. Poor

signaling was also to blame. This drew

the ire of RCT and ultimately helped send the I&GN into bankruptcy in 1908. In

1911, a new I&GN company was organized to take over the assets and operations of

the old company, with the Gould family still in charge. In early 1914, the I&GN

again returned to receivership. Another new company, slightly renamed as the

International - Great Northern (I-GN) Railroad, was formed in 1922 to acquire the

I&GN out of foreclosure, at which point the Gould family was no longer involved.

MP and the T&P likewise gained independence from the Gould family, in 1917.

Freed from Gould control, MP wanted to acquire both the I&GN and the T&P as a means of re-entering the Texas market through the

Texarkana connection. In 1918, MP began to purchase T&P stock on the open market

with an eye toward acquiring a controlling interest. By 1930, MP owned a majority stock interest in the T&P but

did not take operational control. When the I-GN came out of receivership in

1922, MP tried to buy it, but the

sale was nixed by the ICC. Undeterred, MP

helped the New Orleans, Texas & Mexico (NOT&M) Railway buy the I-GN

simply to keep it out of the hands of adversarial railroads.

The ICC approved the NOT&M's purchase of the I-GN in 1924, and then allowed MP to

buy the NOT&M on January 1, 1925. This gave MP the I-GN plus several

railroads that comprised the NOT&M -- a sudden and massive presence for MP in

Texas, particularly along the Gulf Coast centered at Houston where the NOT&M

railroads had been competing with SP's line between Houston and New Orleans.

In 1933, MP went into a lengthy receivership which also compelled receivership for the I-GN. Operating for more than two decades under court

supervision, MP finally emerged from bankruptcy in 1956. MP dissolved the I-GN

at that time and integrated its operations under the MP name. All this time, the T&P and MP

had cooperated extensively in a relationship that remained essentially unchanged into

the 1970s. In 1976, MP finally exercised its ownership control over the T&P by

dissolving the company and merging its assets into MP.

|

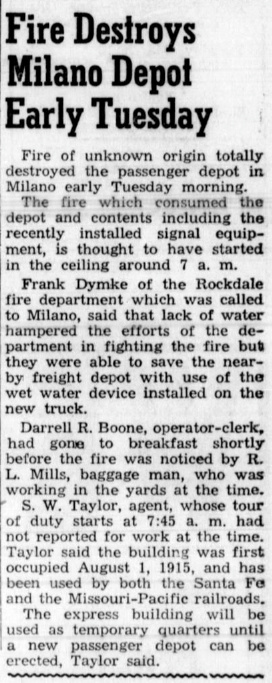

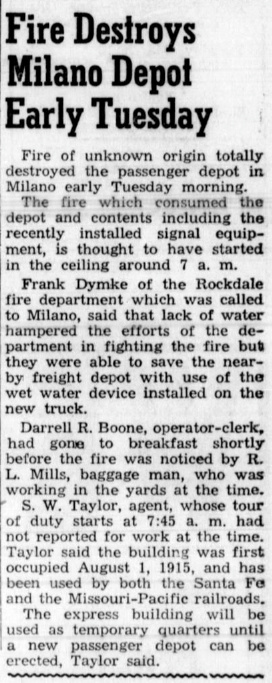

Left: The

Rockdale Reporter and Messenger

of Thursday, March 13, 1952 reported that Milano Union Depot had been

totally destroyed by fire two days earlier. Presumably the "recently

installed signal equipment" that was consumed by the fire pertained to

the interlocker and related communications. The fate of the Tower 23

interlocking plant, any residual functional capability, and how the

crossing was managed in the immediate aftermath of the fire has not been

determined. The story incorrectly reported that the depot opened in 1915

instead of 1914.

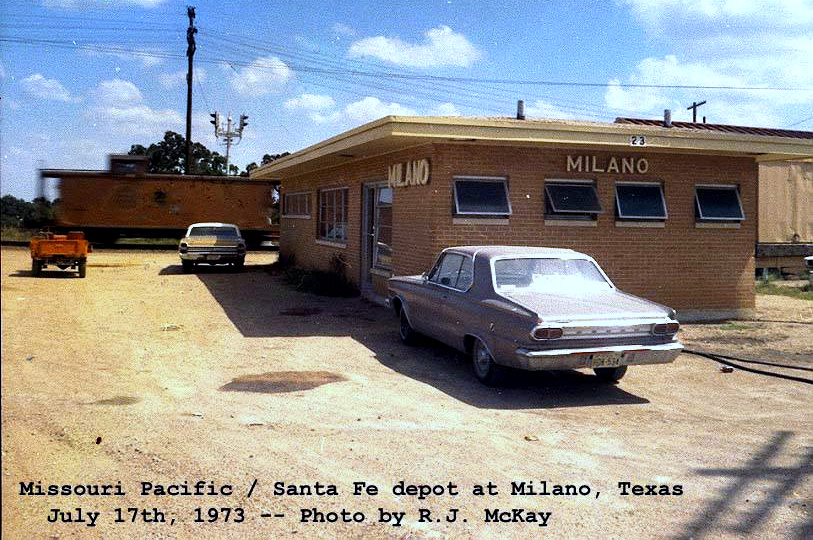

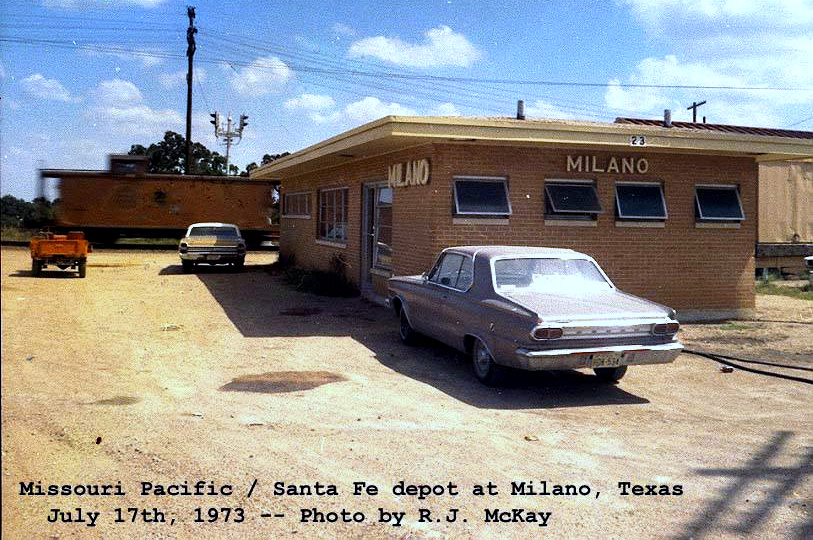

Above Left: In 1954, a new brick passenger depot (R. J.

McKay photo, 1973) opened at Milano, much smaller than the depot that burned. By

the early 1950s, commercial air travel had begun to impact railroad passenger

traffic, and Milano surely experienced this decline. Milano had a tiny

population, hence the passenger depot had always been sized for connecting

passengers. Such traffic had fallen as airlines provided a faster way to travel

between the Midwest and Austin / San Antonio / Laredo / Mexico City. Note the white placard

with black letters "23" present on the roofline showing that the interlocking had been reconstituted

inside the new depot.

Above Right:

This 1989 photo by Tom Kline shows that a white "23" placard was also attached to a

different side of the roofline of Milano's brick passenger depot. The depot closed

in 1982, by which time the interlocking had been converted to an automatic

plant. |

In the early 1970s, Amtrak

passenger trains began to pass through Milano. Amtrak was created to take over inter-city passenger service from most

U.S. railroads. In 1973, Amtrak began running the Inter-American between Fort Worth and Laredo,

extending it the following year

with a St. Louis - Fort Worth segment using the T&P's Texarkana - Fort Worth

tracks. South from Fort Worth, the Inter-American

went to Temple on Santa Fe's main line, but Cleburne

was the only town of any size on this route. The obvious path out of Fort Worth with

a vastly

larger population would

have been to use the Katy's tracks from Fort Worth to Temple via

Hillsboro and Waco, but Amtrak refused to

do so. The Katy tracks were in poor shape, not suitable for passenger

service, and Amtrak did not want to pay for the required upgrades which the Katy

had insisted.

At

Temple, the normal route would be to

go south to Taylor on the Katy's tracks and turn southwest on MP's I-GN route from Taylor to Laredo. Again, Amtrak determined the Katy tracks

were unacceptable. Even though Amtrak would be paying a

recurring fee for the rights to use this 39-mile segment, the Katy had insisted that Amtrak pay

for the track upgrades required for passenger service, including construction of

a connecting track at Temple to facilitate transitioning between the Santa Fe

and Katy rail

lines.

Amtrak refused to spend the money, opting instead to stay on Santa Fe's tracks

to Milano and then turn west toward Taylor on MP's tracks at Tower 23 (via the

west quadrant connecting track.) A Texas Monthly article in August,

1974 did not have good things to say about Amtrak's route choice for the

Inter-American ...

Austin lies southwest of Temple,

but the baffled, homeless Inter-American proceeds southeast toward

Galveston for 44 miles until it finally hits the MoPac tracks about an hour

later at Milano (pop. 380). At this point it is exactly four miles closer to

Austin than it had been in Temple. Reaching Milano it creeps and jerks

indecisively through high grass and empty fields. Said one passenger: “If you

didn’t know the damn thing was on tracks, you’d think it had gotten lost.”

Milano was not a scheduled passenger stop for Amtrak,

but the Inter-American passing regularly through the east connecting track

controlled by Tower 23 may have provided the impetus to automate the interlocker;

this appears to have occurred in 1973. Santa Fe's June, 1973 Employee

Timetable (ETT) gives no indication that Tower 23 had been automated, but the

October, 1973 ETT has an asterisk next to the Milano entry in a table of

Speed Regulations - Railroad Crossings At Grade. The asterisk leads to the

following notation:

At Brenham and Milano, if

controlled signal governing movement over railroad crossing is in stop position,

communicate with control station. If authorized to pass stop signal, before

proceeding a member of crew must go to control box at crossing and follow

instructions therein.

Automatic interlockers usually have a pair of control

boxes to enable a train crewmember from either railroad to override the signal

that's restricting his train's movement, as this notation describes. In an ETT dated January, 1975, Santa Fe began explicitly

describing the interlocker at Milano as Automatic. The interlocking upgrade was

surely appropriate; by this time there were

numerous automated plants in use at Santa Fe crossings around the state. Amtrak and the Katy

continued negotiating, and with the help of local governments, reached an agreement for Amtrak to upgrade and

use the line from Temple to Taylor. On October 26, 1975, the

Inter-American began using the Katy's tracks between Temple and Taylor, no longer passing through

Milano.

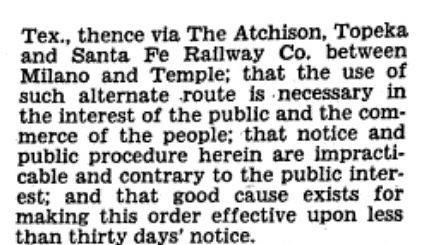

Left

and Above:

This ICC order issued June 5, 1978 authorized Amtrak to use the west

quadrant exchange track at Milano to reroute its passenger trains

between Temple and Taylor. The Katy tracks between the two towns were

temporarily out of service due to a major derailment. Left

and Above:

This ICC order issued June 5, 1978 authorized Amtrak to use the west

quadrant exchange track at Milano to reroute its passenger trains

between Temple and Taylor. The Katy tracks between the two towns were

temporarily out of service due to a major derailment. |

Below: This equipment

cabinet at the Milano crossing was lettered for its contents, the

automatic interlocking plant that replaced Tower 23's manually-operated

plant. (Jim King photo, 2005)

|

Above Left: Ken Stavinoha

provides this photo of the 1916 Santa Fe freight depot. Ken explains... "It would have been located WNW of the joint

passenger depot on the 1915 Katy Diagram somewhere along the siding shown. Image

is undated, but is probably from the 1930-era inventory that Santa Fe

performed." Above Right:

Another photo provided by Ken shows the inside of the Santa Fe manual override

box for the automatic interlocking with operating instructions posted at the

top. The box is now owned by the Eagle Lake Depot Museum.

In October, 1979, the Inter-American began

carrying the remnants of Amtrak's Lone Star, which had been a Chicago -

Houston route. At Temple, Houston-bound cars were separated from the

Inter-American and pulled to Houston by an Amtrak locomotive via Milano,

Brenham and Rosenberg. In October, 1981, the

Inter-American name was retired, the train becoming the Texas

Eagle. The Temple - Houston and San Antonio - Laredo segments were

eliminated, hence Milano ceased to see Amtrak trains except for the rare reroute

caused by track disruptions.

Above Left: In

August, 1975, Gary Morris photographed a southbound Inter-American

moving onto the west connecting track toward the MP rails to Taylor.

Above

Right: Google Earth satellite

imagery from 2024 shows that none of the connecting tracks remain intact

at Milano.

The diamond at Milano continues to see

substantial traffic, the two railroads being Union Pacific (UP) and

Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF.) MP was acquired by UP in 1982 and was

merged fully into UP in 1997. The former I-GN route through Milano is now part

of a UP

main line between St. Louis and Laredo, just as originally envisioned. In 1965,

the GC&SF became fully merged into AT&SF, and thirty years later, AT&SF merged with Burlington Northern

to form BNSF. The former GC&SF route through Milano is now a BNSF main line

between Galveston and Temple, extending northward through Fort Worth and

Oklahoma City into Kansas.

Above Left: Milano's automatic

interlocking cabinet is seen in full sitting to the left of the cabin it

replaced, which likely dates to the original conversion in the early 1970s. The

utility pole near the center of the image hosted the control manual override

boxes for the interlocker. The view is to

the south; the cabins are in the south quadrant of the diamond where Tower 23

stood originally.

Above Right: This photo was

taken from the west quadrant at Milano showing BNSF #4329 leading ATSF #8712

southeast toward Caldwell and Brenham. (both photos, Jim King, 2005)