Texas Railroad History - Tower 18 (Joint Track) and Tower 60 (North Fort

Worth)

Two Towers on the

North Side of Fort Worth

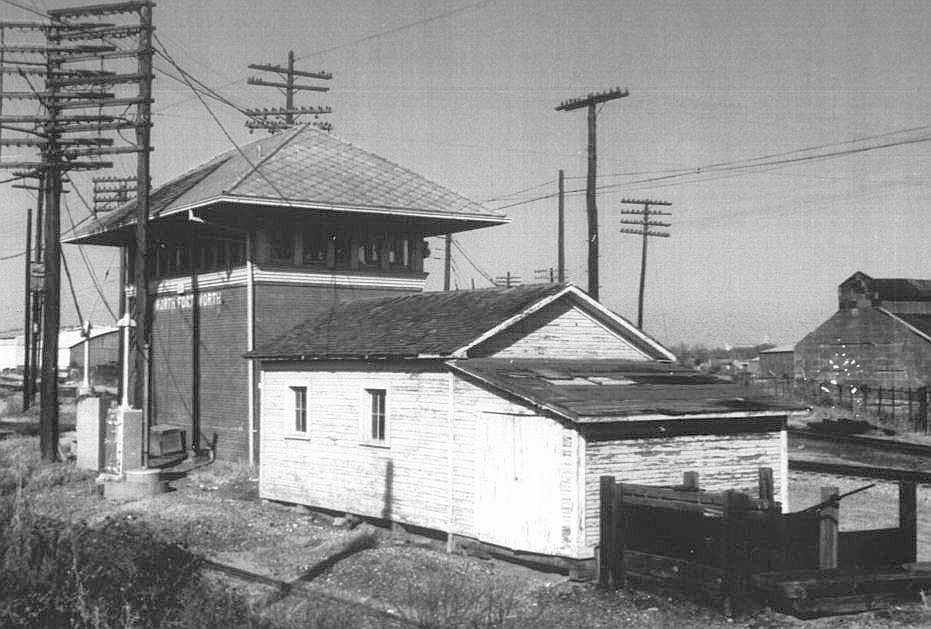

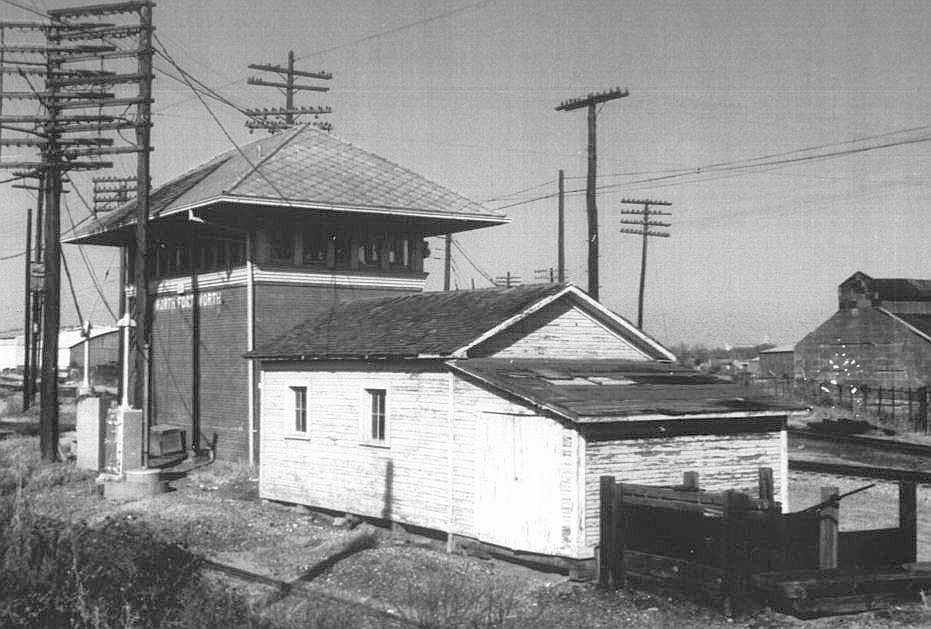

Above: When Tower 60 was

commissioned in 1905, it was probably not this building. Photographed by Gary

Morris in October, 1976, it

doesn't look seventy years old, but more significantly, its brick construction

would be substantially out of character for Santa Fe, the railroad that built

it. Other large towers built in Texas by Santa Fe used wood construction, e.g.

compare Tower 57, which opened in downtown Dallas

eight months before Tower 60, and Tower 19, which

opened two years earlier in south Dallas. Unfortunately, definitive

proof of what, if anything, may have preceded this structure (and if so, where,

precisely, it was

located) is lacking.

Tower 60 was identified by the Railroad Commission of Texas as "North Fort Worth", the town in which it was located.

The town didn't last long, but the tower's identity remained unchanged for the

duration of its existence.

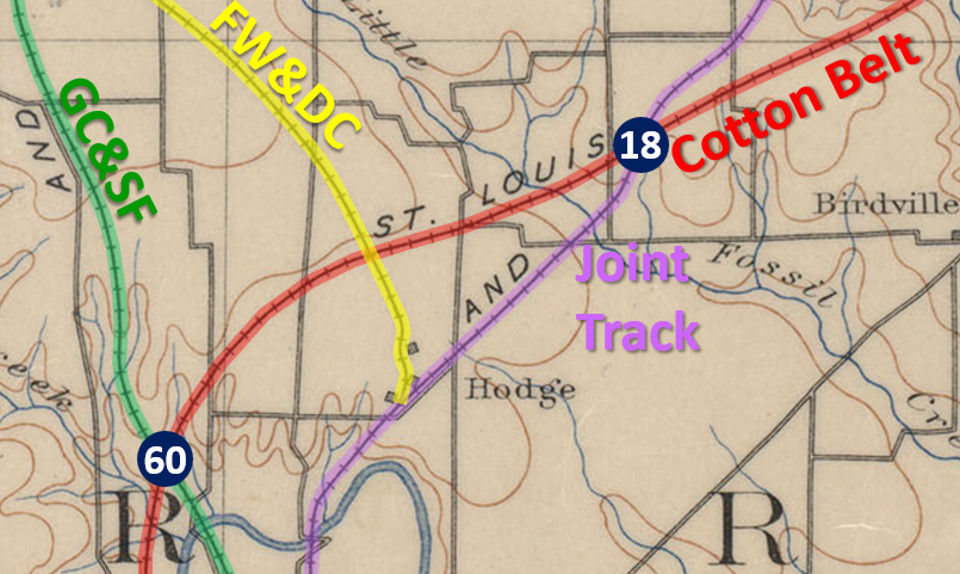

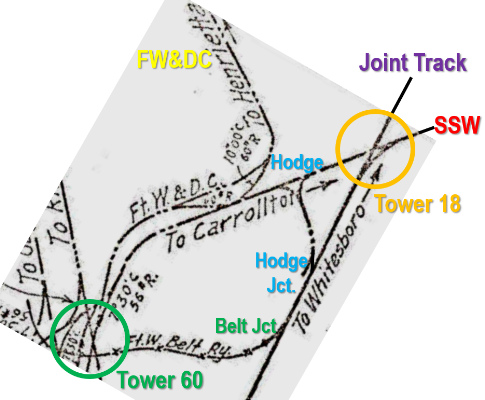

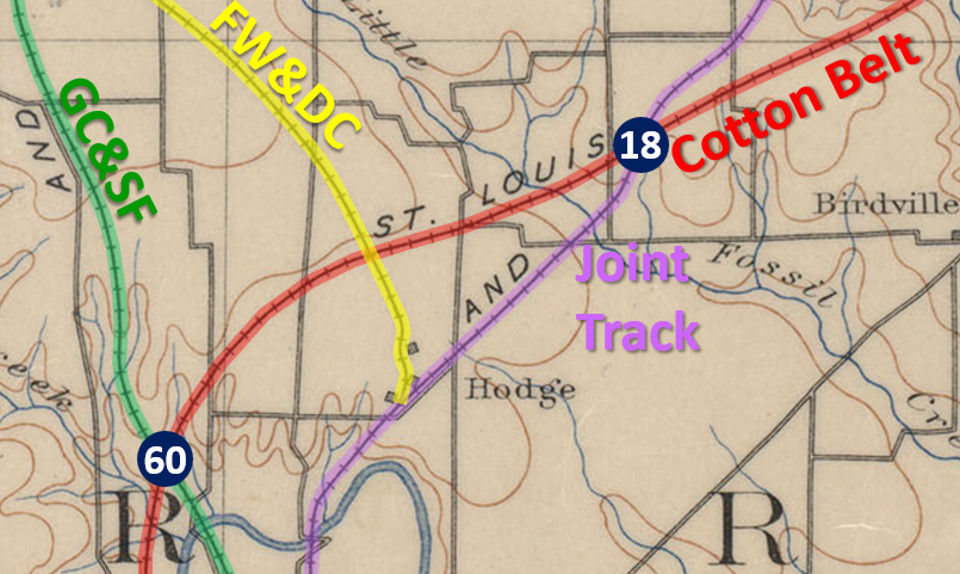

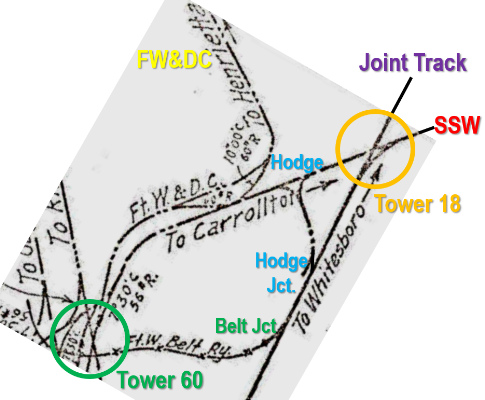

Below:

Annotations on this 1889 topographic map of Tarrant County show the (future)

locations of Tower 18 and Tower 60, approximately four miles apart. Although the

roads on the map suggest a semi-rural area, the towers were only about 3 - 4 miles

north of downtown Fort Worth. Four railroads had laid

tracks into the area: the Fort Worth & Denver City (FW&DC) Railway; the Gulf,

Colorado & Santa Fe (GC&SF) Railway; the St. Louis, Arkansas & Texas (SLA&T, "Cotton

Belt") Railway; and the "Joint Track" built by the Texas & Pacific Railway that

was shared with the Missouri, Kansas & Texas Railway under a long term rights agreement. When Tower 18 was commissioned in

1903, the annual interlocker summary report published by the Railroad Commission

of Texas

identified its location as "Joint Track". Its identity changed to

"North Fort Worth" in the report published at the end of 1923, and it was

re-identified as "North Fort Worth (Hodge)" at the end of 1927.

The origin of the name "Hodge" applied to an area

near the stockyards in north Fort Worth has not been determined. The earliest

newspaper reference found so far is from the Fort

Worth Daily Gazette of September 24, 1883 where Hodge is mentioned as a

locale "...about four miles north of this city.", a statement

made in the context of a community where someone lived. At the end of 1927, the Railroad Commission of Texas (RCT) reported Tower 18's

location as "North Fort Worth (Hodge)" even though Tower 18 was more than two miles away

from both of the places that traditionally had been referenced as "Hodge" by the

railroads. The first of those was

a switch on the Joint Track where the Fort

Worth & Denver City (FW&DC) Railway began building north toward Wichita Falls

on November 27, 1881. (In 1951, "City" was dropped, becoming simply the "FW&D".) At some point, the switch became known as "Hodge Junction",

but whether the general area was already referenced

as "Hodge" when construction began is undetermined. The other "Hodge" was about

a mile north of Hodge Junction

where tracks of the St. Louis, Arkansas & Texas (SLA&T, "Cotton Belt")

were built across the FW&DC in 1888. Northeast of both Hodge and Hodge Junction,

Tower 18 opened in 1903 where the Cotton

Belt crossed the Joint Track.

The first railroad to reach the future site of Tower 18 was the

Texas & Pacific (T&P) Railway, building from

Sherman to Fort Worth in 1881. By then, the T&P was controlled by rail magnate Jay Gould, who had established a

syndicate to purchase the stock of T&P President Thomas Scott for $3.5

million. Gould had formed a construction

company which the T&P had hired to build the remainder of the railroad to

El Paso and beyond. The T&P's effort to build a

transcontinental rail line from Texarkana to San Diego had begun in 1873 when

construction started on two parallel main lines west from Texarkana. The

northern route went via Paris to Sherman, 154 miles; the southern route went south to Marshall and then

west to Fort Worth, 248 miles. At those endpoints,

construction on both lines stopped in 1876, impacted by the

Panic of

1873 which had dried up railroad financing. Gould took over the T&P and

restarted construction in 1879 -- his syndicate would build the line from Fort

Worth to El Paso

in exchange for $20,000 in T&P stocks and $20,000 in T&P bonds for each mile

completed. As construction proceeded, Gould progressively gained financial

control of the T&P and was named President in April, 1881.

The T&P's track construction never reached El Paso, stopping instead at Sierra

Blanca where a deal between Gould and Southern Pacific (SP) Chairman C. P.

Huntington resulted in the T&P sharing SP's track into El Paso.

Towns on the T&P's northern route needed to be able to reach the line to El Paso, so Gould

laid tracks between Sherman and Fort Worth. He

elected to route due west from Sherman to Whitesboro and then proceed southwest to Fort Worth. In isolation, this would have been an odd

routing, but it was chosen to allow the Missouri, Kansas & Texas (MK&T, "Katy")

Railway to reach Fort Worth over the T&P's tracks.

Gould had become President of the Katy in 1879, and the

Katy already had a line from Denison to

Gainesville that passed through Whitesboro. With the T&P and MK&T both under Gould's control, the two

railroads signed a long term rights agreement to share the so-named Joint Track

between Whitesboro and Fort Worth. General Grenville M. Dodge had been on the

T&P's Board of Directors from the beginning, and with Gould's ascension, Dodge

had resumed his role as the T&P's Chief Engineer. Dodge was famous as the Chief Engineer for Union Pacific (UP) responsible for

the construction of the eastern part of the Transcontinental Railroad, completed

in 1869.

Gen. Dodge had spent significant time in Fort Worth over several

years and he was familiar with its numerous rail projects,

one of which was the FW&DC. It had been chartered on June 6, 1873 with a plan to

build through the Texas Panhandle to meet Colorado & Southern (C&S) rails coming

south from Denver. The Panic of 1873 along with other financial and

organizational obstacles had prevented the start of construction, hence the

stockholders were receptive when Dodge offered to build the FW&DC under the same stock and bonds arrangement Gould had used for the T&P

(and likewise, Dodge eventually became President of the FW&DC.) As this was

the FW&DC's initial construction, it did not

yet have tracks into downtown Fort Worth, and obtaining a right-of-way

would be time-consuming and expensive (Fort Worth already had 6,000 residents.) Instead, Dodge elected to use the Joint

Track as a means for FW&DC trains to reach downtown passenger facilities.

[Presumably Dodge had no difficulty negotiating the agreement to use the Joint Track;

he was still the T&P's Chief Engineer!]

Dodge chose a location on the Joint Track

about a mile and a half north

of the Trinity River to be the starting point for the FW&DC's construction

which commenced in

November, 1881. Whether the "Hodge" name had been applied to this area by then

is undetermined, but the location became known as "Hodge Junction". Dodge made

rapid progress; FW&DC trains were operating forty miles to Decatur by May, 1882.

The initial construction segment, 110 miles to Wichita Falls, was completed in

September, 1882. By April, 1888, the connection with the C&S had been

accomplished and trains were operating between Denver and Fort Worth. Just over a

mile north of Hodge Junction, the FW&DC built a freight yard that eventually was known as "North Yard."

By 1910, the FW&DC was owned by the C&S but continued to operate independently.

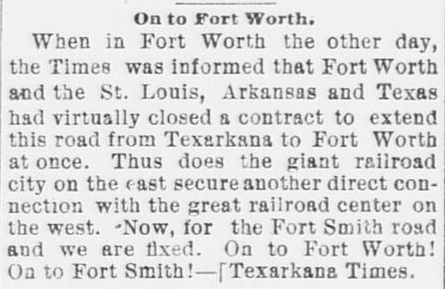

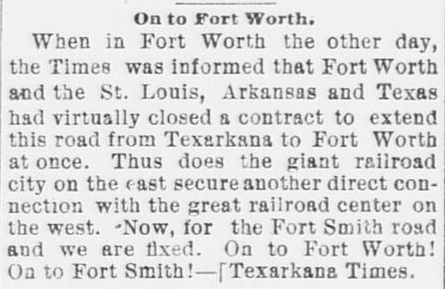

Below: The Fort Worth Daily Gazette of

June 4, 1887 quoted a recent news item from the Texarkana Times

announcing a contract to build an extension of the SLA&T west to Fort

Worth. The construction would be completed in less than a year.

|

In 1887, the SLA&T began building a branch line

west from Mt. Pleasant, a town between Texarkana and

Big Sandy on the main line that had been built in 1880 by

the Texas & St. Louis (T&SL) Railway. At Commerce, 57 miles west of Mt. Pleasant, the line split into two branches, one

of which went

to Sherman via Wolfe City and Whitewright (much of the right-of-way is

now Texas Highway 11)

The other branch went to

Greenville and Plano,

passed north of Dallas (where a spur was

later built into downtown), and continued west through

Carrollton. Entering Tarrant County, it

turned southwest toward Fort Worth, crossing the Joint Track

at the future site of Tower 18. A couple of miles farther west, the SLA&T crossed the FW&DC.

A rail yard known as "Hodge" was built at the crossing, which was just

under a mile north of Hodge

Junction.

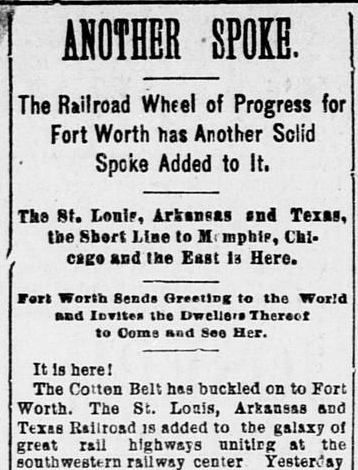

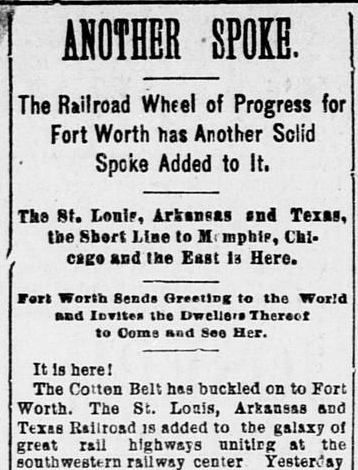

Right:

The Fort Worth Daily Gazette of

April 3, 1888 reported the arrival of the SLA&T into Fort Worth. Although

"Cotton Belt" became synonymous with the SLA&T's 1891

successor, the St. Louis Southwestern Railway, this news item shows that

the moniker had long been adopted by the SLA&T, inherited from its predecessor,

the T&SL. The newspaper greeted "the

World" on behalf of Fort Worth, but did any "Dwellers Thereof" accept the invitation to visit? |

|

Well prior to the SLA&T's construction into Fort Worth, Jay Gould

viewed the Cotton Belt as a threat to his

business. Gould had assembled a rail network under his Missouri Pacific (MP)

enterprise that operated into Texas from St. Louis via gateways at Texarkana and Denison,

and he had leased both the T&P and the Katy to MP as part of this effort. In direct competition

to MP, the T&SL had expanded rapidly. By 1883, it was operating from Bird's Point,

Missouri on the Mississippi River to Waco and

Gatesville via

Texarkana. This expansion overextended the T&SL, largely because it

lacked the passing sidings and rolling stock necessary to run a lengthy, single-track railroad efficiently.

Although the T&SL entered receivership in 1884,

doing so helped keep the railroad from falling

into Gould's hands.

In February, 1886, the SLA&T was created by the

bankruptcy judge to become the new Cotton Belt, going against the advice of its

President, Sam Fordyce, who believed there were operational issues that would

inhibit profitability. Despite Fordyce's concerns, the receivership ended and within a year, the SLA&T

had decided to build the

new branch lines into north Texas hoping to compete with Gould on traffic from

Sherman and Fort Worth. This culminated in a secret agreement between Fordyce

and Gould

in 1888 for the Cotton Belt and MP to cooperate on traffic through Texarkana.

Through loans and stock purchases, Gould gained financial leverage over the

SLA&T, positioning him to guide its reorganization when it became insolvent in 1889. The new company created in 1891 was called the St. Louis Southwestern Railway

(SLSW or SSW, but always the "Cotton Belt", which Gould had wanted as its official name.) It was

headed by Gould's younger son, Edwin, who

remained the Cotton Belt's President until he retired in 1925. Subsequently, a series of ownership

changes resulted in the Cotton Belt becoming a subsidiary of SP in 1932.

|

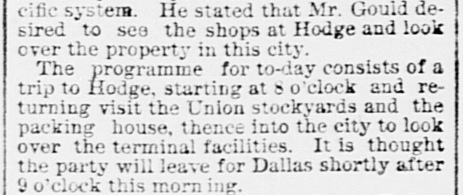

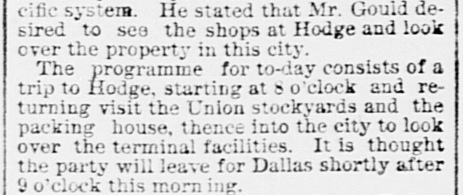

Left: Jay Gould visited Fort Worth in April,

1891 to view the stockyards and the Cotton Belt shops at Hodge. He died

from tuberculosis in New York in December, 1892. (Fort

Worth Gazette, April 11, 1891)

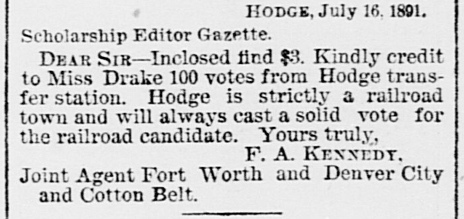

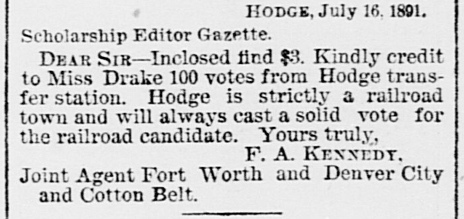

Right: Hodge was never

incorporated, but the residents viewed it as "a railroad town", in this

case, voting on who should receive a scholarship offered by the

newspaper. Note that a "Joint Agent" served both railroads, apparently

sharing a "transfer station" at Hodge. (Fort Worth

Gazette, July 18, 1891) |

|

The SLA&T's April, 1888 arrival into Hodge included

track-laying a couple of miles farther west to the

stockyards where cattle shipping had become a major source of traffic. To avoid the time and expense of obtaining a right-of-way to reach downtown

passenger stations, the Cotton Belt had two choices: negotiate an agreement with the GC&SF

for the use of their track from the stockyards, or use the Joint Track,

as the FW&DC had done. Presumably, Gould and Fordyce were already having the

discussions that would lead to their secret agreement, so it is unsurprising that the

Cotton Belt chose the Joint Track -- the Cotton Belt's use of T&P's

passenger station may have been part of the agreement. There were two ways for

the Cotton Belt to

access the Joint

Track: use the FW&DC track between Hodge and Hodge

Junction, or connect to the Joint Track at their mutual crossing, the

future site of Tower 18. Both routes appear to have been used at varying times,

and at least by 1913 (and probably much earlier), a connecting track was in place at Tower 18 to support Cotton Belt access to the Joint Track.

A 1913 SLSW

employee timetable (ETT) states: "S.L.S.W trains

occupying track between S.L.S.W. Crossing and T. &. P. Passenger Station at Ft.

Worth will be governed by rules and time table of the M. K. & T. and T. & P.

Joint Track." If it seems odd that the Cotton Belt ETT's name for the Tower 18

crossing was the

self-referential "S. L. S. W. Crossing", it served to make these

instructions consistent with the name used by the Joint Track ETT under

which trains operated to reach downtown.

|

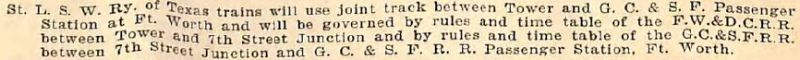

Left:

This snippet of a 1915 MK&T track chart (courtesy, Ed Chambers) has been

annotated and re-oriented so that North is up. The track diagram (not

drawn to scale) shows both routes for Cotton Belt passenger trains to

access the Joint Track: a connection in the southeast quadrant of

Tower 18, and the track between Hodge and

Hodge Junction. The "Ft. W. & D. C." label along the north track west of

Hodge shows where the FW&DC had built its own line into downtown c.1890

by curving through the northwest quadrant at Hodge and proceeding downtown via Tower 60. The track chart does not show a Cotton Belt /

FW&DC crossing at Hodge; the date this diamond was eliminated is undetermined, but it was likely soon after the FW&DC built its

line into downtown. After that time, there would have been little need

for the FW&DC to operate between North Yard and Hodge Junction. The

track between Hodge and Hodge Junction remained intact and appears to

have been used by the Joint Track railroads as a convenient means for

exchanging freight with the FW&DC and Cotton Belt. Note also the

"Ft. W. Belt Ry." label, identifying the Fort Worth Belt Railway that

connected to the Joint Track at Belt Junction.

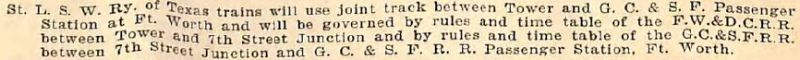

Above: With an

unfortunate reference to "joint track" that was

not the T&P/MK&T Joint Track, this 1927

Cotton Belt ETT explains that trains will share FW&DC and GC&SF tracks

south of "Tower" (Tower 60) to access the GC&SF Passenger Station

downtown. Previously, the T&P Passenger Station had been used, as noted

in the aforementioned 1913 Cotton Belt ETT. Precisely when the station change occurred is undetermined,

but a good guess might be the period under the supervision of the U. S.

Railroad Administration during World War I. |

The lifespan of the Joint Track connector at

Tower 18 is unknown, but it seems likely that it was retained after

the Cotton Belt shifted passenger operations to the Santa Fe station. The

connector provided an alternate route

into downtown Fort Worth for Cotton Belt passenger trains seeking to avoid

congestion at Hodge Yard or Tower 60. The connector does not, however,

appear on a 1952 aerial image. Unfortunately, neither Tower 18 nor Tower 60 are

covered by Sanborn Fire Insurance maps of the era.

In 2004, Chuck Harris provided

his recollections of Hodge:

Glad to help out with the SSW/T&P-MK&T crossing near

Hodge. The place was called Swestern on the Cotton Belt. It wasn't

very far from the SSW yard office at Hodge and the T&P-MKT

yard office at Hodge. The two railroads were about a mile or so

apart and made a gradual slant toward each other before crossing.

You could see the crossing of the two railroads from North Sylvania

Ave grade crossing which was at the east end of the SSW yard.

I would say a mile or so. Yes, there was a tower there, but probably

gone by 1925 or 26. A 1916 dispatcher's train sheet for the SSW

shows a telegraph call for that location which would indicate

it was occupied.

Chuck refers to the "T&P-MKT yard office at Hodge" which

would indicate that the Joint Track railroads took over the former

FW&DC track segment between Hodge Jct. and Hodge. This probably

occurred in 1891; the track was no longer needed by the FW&DC, and with

both the Cotton Belt and the T&P under Gould's control, it would make

sense to share the yard. [MP's lease of the Katy was voided by court

order in 1891, but the Joint Track agreement remained in place,

and the Katy would also have wanted access to the yard at Hodge.] The 1915 track chart

shows connections in both directions at Hodge, but in only one direction

at Hodge Junction.

Right: In

this 1952 aerial view of Hodge Junction ((c)historicaerials.com), the

Joint Track slants across the right side of the image at a 45-degree

angle. The original location of the FW&DC switch on the Joint Track is

at the bottom of the image, with the track to Hodge curving up and to the

left. Across the triangle from the switch, a right-of-way is plainly

visible, perhaps with its track still intact. This connector was added

at some point to permit southbound Joint Track movements to go north to

Hodge, or vice versa. It also gave the Joint Track railroads a wye.

Although the right-of-way -- and perhaps the track -- for this connector

survived long enough to be visible in this 1952 image, the

connector right-of-way does not appear on 1956 imagery.

Although Hodge Junction did

not develop an extensive yard, the image shows spur tracks adjacent to

the Joint Track main line. Whether these were used for a general purpose

or a specific business is undetermined. The rail yard a mile north at Hodge evolved and expanded over

the years, adding yard tracks and connectors to facilitate traffic exchange among the Cotton

Belt, the Joint Track railroads and the FW&DC. |

|

Gould owned a controlling interest in

the T&P, but he had very little ownership in the Katy, having been elected President through the efforts of his henchmen who had infiltrated the Katy's

executive ranks over several years. This left Gould vulnerable to the will of

the Katy's stockholders, and they had become very unhappy with the lopsided lease

terms that Gould had imposed on the Katy, essentially draining Katy profits

directly into MP's bottom line. Gould was fired from his position as Katy

President during a stockholders' meeting in May, 1888. By then, extensive legal

proceedings against the Katy were already underway by the Texas Attorney General. More legal proceedings ensued when the new management of the Katy

sought bankruptcy protection after firing Gould. [A major issue in all of

this legal wrangling was the disposition of the International & Great Northern,

Texas' largest railroad, which Gould had acquired and leased to the Katy -- a

story best told elsewhere.] In 1891, a court order

canceled MP's lease of the Katy, making it

independent, no longer legally or financially tied to Gould. Gould

died in late 1892, and his empire was taken over

by his son George, who remained President of the T&P until 1917.

Tower 18 was commissioned on July 25, 1903; at the time, the T&P and Cotton Belt were both headed by sons of Jay Gould,

George and Edwin, respectively. The crossing was at an acute angle, and the

tower was located in the obtuse southeast quadrant of the diamond. RCT's 1903 Annual Report

lists a

12-function / 12-lever Union Switch & Signal mechanical interlocker. Twelve functions was the minimum standard configuration for a

crossing of two railroads, consisting of a home signal, distant signal and derail

in each of the four directions. RCT documentation shows that the tower was operated by

T&P personnel which suggests that the tower had been built by the T&P.

The crossing existed before 1901, so RCT

regulations required the two railroads to split the capital cost of the tower and interlocking plant evenly. In this particular case, the recurring

operations and maintenance (O&M) expenses would also have been split evenly

because each railroad used half of the twelve functions. Although the Katy sent

substantial

traffic through Tower 18, RCT did not show it officially obligated for a share of O&M expenses because the Joint Track

was formally owned by the T&P. The T&P's share of recurring expenses would have been

split with the Katy under their trackage rights agreement.

Tower 18's

function count was unchanged from 1903 through 1929, but RCT's

interlocker table dated

December 31, 1930 (the last such table to be published) reported the function count reduced to eight and the interlocking plant converted to automatic. Most likely, the four functions eliminated were

the derails in each direction. Experience across the country had shown

that derails created more problems than

they solved when used as protection for crossing diamonds (they remained

valuable to prevent unplanned movements of railcars from industry spurs and yard tracks.) On March 31, 1930, RCT held a hearing to discuss two automatic

interlockers without derails that the FW&DC had proposed for

Lubbock and

Plainview. The proposal was accepted by RCT on May 1, 1930, hence

Tower 141

(Lubbock) and Tower 142 (Plainview) were the first

towers to get initial commissioning by RCT as

automatic interlockers. They were installed in

February and March, 1931, respectively, dates that somehow managed to be reported in a table dated December 1, 1930! That same table lists two other

interlockers as automatic: Tower 11 (West Orange) and Tower 18, both of

which had been listed as mechanical in the prior year's table. A letter

in the RCT interlocker archives at DeGolyer Library, Southern

Methodist University, states that Tower 11's conversion was actually completed

in June, 1931. The precise date of

Tower 18's conversion has not been determined, but it's possible that it was the

first operational automatic interlocker in Texas.

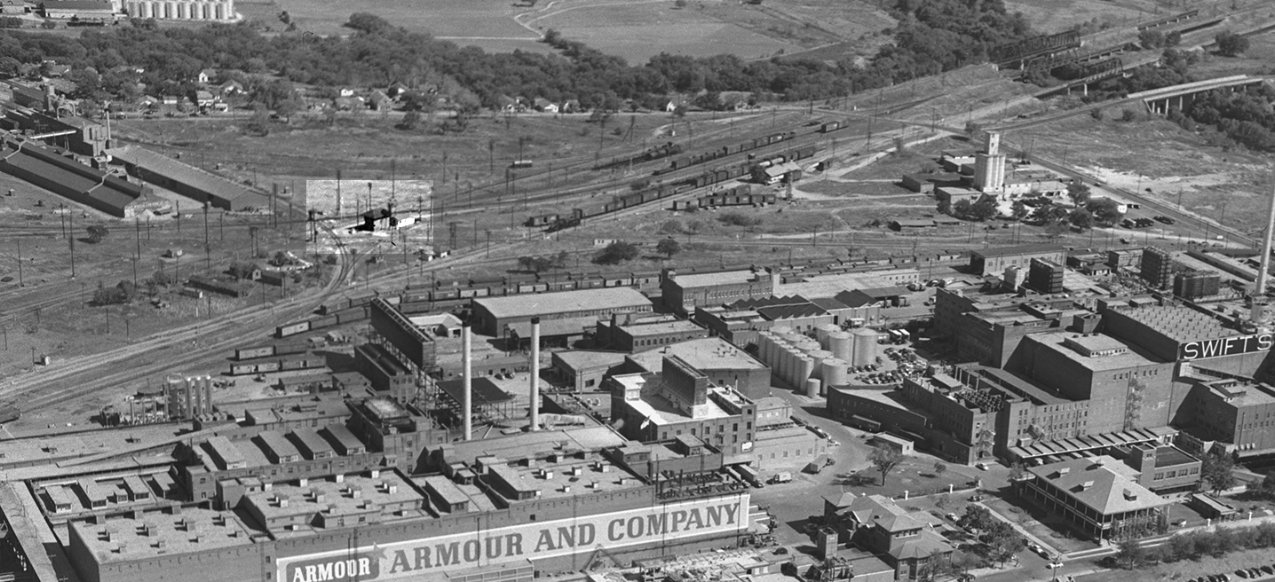

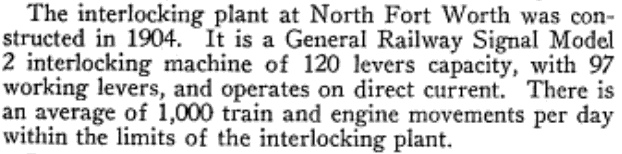

Above: The stockyards had evolved from a cattle shipping

location in the late 1880s to become a cattle processing and meat-packing center

by the mid 1890s. In 1895, the

Fort Worth Stockyards and Belt Railway was chartered to provide switching

services for the stockyards and associated processing plants. The following

year, "Stockyards" was dropped from the railroad's name, becoming simply the

Fort Worth Belt (FWB) Railway. By 1902, large processing and packing facilities

had been built by Armour and Swift, two national meat companies. This map of the

vicinity of Tower 60 was published by the Interstate Commerce Commission in its

1918 valuation report for the FWB, which connected with the Tower 60 railroads

and to the Joint Track railroads via Belt Junction. Frisco Jct. was where

the Cotton Belt intersected the St. Louis & San Francisco ("Frisco") Railway,

which had its major yard in south Fort Worth. For several years, Frisco operated

between Carrollton and Frisco Jct. using Cotton Belt trackage rights. The town of Niles City (light pink)

represented yet another attempt to incorporate the area around the stockyards to

prevent encroachment by the growing city of Fort Worth.

Less than two miles west of Hodge,

multiple railroads passed through an area adjacent to the Fort Worth Stockyards

that would eventually become the site of Tower 60.

The first was the GC&SF, laying tracks north from Fort Worth in 1886 toward

Purcell, Indian Territory (Oklahoma) where it would meet a construction crew of

the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe (AT&SF) building south from Kansas. The

connection of the two railroads was part of an agreement under which the

GC&SF would become a wholly-owned subsidiary of the AT&SF in 1887. The GC&SF had

been looking for ways to stimulate out-of-state import/export traffic through

the Port of

Galveston, the city where it was headquartered. At the

same time, the AT&SF was seeking an efficient export outlet for Midwest grain

and other agricultural

commodities. Becoming part of Santa Fe

strengthened the GC&SF, which grew to have a major presence in Texas railroading.

|

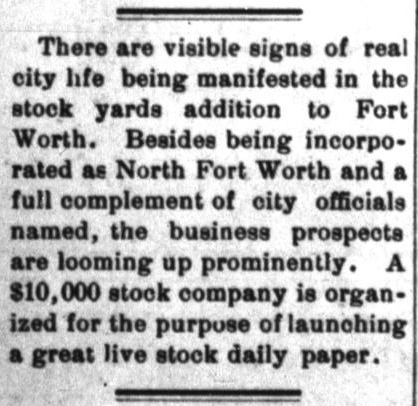

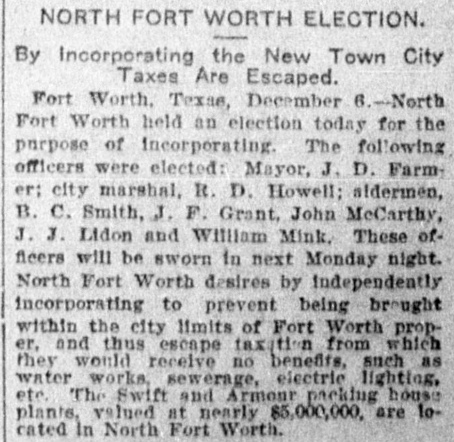

By the turn of the century, the

stockyards and meat-packing plants had grown to become a massive

economic engine for Fort Worth. To protect the area from taxation

by the City of Fort Worth, a new town was incorporated as North Fort

Worth in an election held in November, 1902. Reportedly, the vote was

170 - 1.

Left Top:

Dallas Southern Mercury, November

13, 1902

Left Bottom:

Mineral Wells Weekly Index,

November 14, 1902

Right: The new town

held its first municipal election in December, 1902 (Houston

Post, December 7, 1902)

State law allowed larger

cities to annex nearby incorporated areas of limited population. The

1909 Fort Worth City Charter officially abolished North Fort Worth and

took over its debts, but did not immediately incorporate the stockyards. In

February, 1911, a new town, Niles City, incorporated the stockyards

vicinity

with 508 residents. When a January, 1921 state law set a threshold of 2,000 residents

for towns to be able to prevent annexation, Niles City quickly expanded

its boundaries to reach that number. The Legislature responded six

months later by raising the threshold to 5,000 residents, and Niles City

soon met its demise, annexed by Fort Worth on August 1, 1923. |

|

After the FW&DC had passed near the stockyards when

building its own line into downtown in 1890, the Chicago, Rock Island & Texas

(CRI&T) became the fourth railroad to enter the vicinity. The CRI&T was a

Texas-based subsidiary of the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific (CRI&P), a major

Midwest railroad. The CRI&T had crossed the Red River into Texas near Ringgold

in 1892 and continued south, ostensibly heading toward Weatherford, a town on

the T&P's line west of Fort Worth. Having reached Bridgeport 32 miles shy of

Weatherford, Rock Island amended its charter and turned southeast to build to

Fort Worth. It arrived on August 1, 1893, passing

through Saginaw and the stockyards area en route to downtown. Ten years later, the CRI&P chartered the Chicago, Rock Island

and Gulf (CRI&G) to build from Fort Worth to Dallas and to absorb the CRI&T and

two other Texas-based subsidiaries of the CRI&P. State law required railroads

owning tracks in Texas to be headquartered in state, hence, the CRI&G was based

in Fort Worth and owned all of the CRI&P subsidiary tracks in Texas.

Rail service to the packing plants and the stockyards created a complex web of

tracks filled with switch engines plus main line freight and passenger trains

heading into and out of downtown Fort Worth. To manage this tangle of connecting tracks and

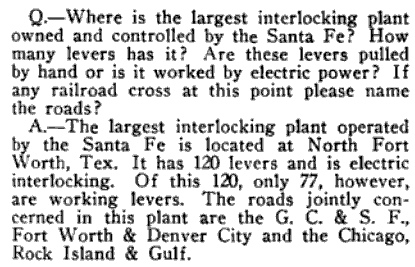

crossing diamonds, Tower 60 was commissioned by

RCT on July 1, 1905. The tower's location was identified as "North Fort Worth"

and its electrical interlocking plant had 83 functions, a huge number indicative of the complexity of the track

network. Among Texas interlocking plants, Tower 60's function

count was exceeded

only by the 122 functions in effect

at Tower 55 in downtown Fort Worth. Tower 60 would

fall to fourth place by the end of

1930, surpassed only by Tower

55, Tower 106 in Dallas and

Tower 26 in Houston.

Tower 60 was built by

Santa Fe, which was also responsible for staffing. Santa Fe shared the recurring

O&M expenses with the Cotton Belt, the FW&DC, the Rock Island and the Fort Worth

Belt on a "weighted function"

basis, i.e. the number of interlocking functions allocated to each individual railroad

compared to the total number of functions in the plant. Since all five railroads

had built through the area prior to 1901, the capital cost of the tower and its

interlocking plant would have been shared evenly among them.

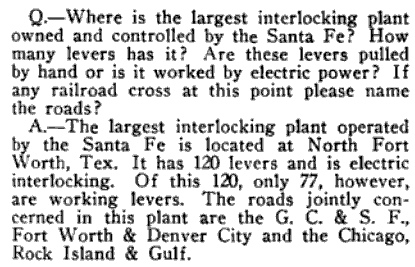

Left:

a question in the Q&A column of a 1914 edition of Santa Fe

Magazine

Another

railroad that operated through Tower 60 at various times was the St. Louis, San

Francisco & Texas, a subsidiary of the St. Louis & San Francisco ("Frisco")

Railway, a major Midwest railroad. In

the early 1900s, the Frisco and Rock

Island railroads were led jointly by B. F. Yoakum, a native Texan who had risen to

the top after executive stints with the San Antonio &

Aransas Pass Railway and the GC&SF. Yoakum was an expert in Texas

railroading, and he sought to expand the networks of the Frisco and Rock Island

in state. To compete against Santa Fe for livestock shipments from the vast

range southwest of Fort Worth, the Frisco purchased controlling interest in the Fort Worth & Rio Grande

(FW&RG) Railway in 1901. It had tracks from Brownwood to Fort Worth, a shorter,

direct line compared to Santa Fe's route from Brownwood via

Temple. The following year, a new Frisco

line entered Texas from Oklahoma. It shared the Katy's bridge over the Red

River, used SP trackage rights to reach Sherman, and then built a new line south to Carrollton. Yoakum negotiated trackage rights on

the Cotton Belt to allow Frisco trains to reach Fort Worth from Carrollton. The

connecting point in Fort Worth was Frisco Junction, about a half mile south of

Tower 60 where the Cotton Belt intersected a new 4.5-mile Frisco track that led

to a new yard in south Fort Worth that had been opened along the FW&RG main line.

Frisco Junction was very close to the stockyards, which Frisco served with

industry spurs.

Another

railroad that operated through Tower 60 at various times was the St. Louis, San

Francisco & Texas, a subsidiary of the St. Louis & San Francisco ("Frisco")

Railway, a major Midwest railroad. In

the early 1900s, the Frisco and Rock

Island railroads were led jointly by B. F. Yoakum, a native Texan who had risen to

the top after executive stints with the San Antonio &

Aransas Pass Railway and the GC&SF. Yoakum was an expert in Texas

railroading, and he sought to expand the networks of the Frisco and Rock Island

in state. To compete against Santa Fe for livestock shipments from the vast

range southwest of Fort Worth, the Frisco purchased controlling interest in the Fort Worth & Rio Grande

(FW&RG) Railway in 1901. It had tracks from Brownwood to Fort Worth, a shorter,

direct line compared to Santa Fe's route from Brownwood via

Temple. The following year, a new Frisco

line entered Texas from Oklahoma. It shared the Katy's bridge over the Red

River, used SP trackage rights to reach Sherman, and then built a new line south to Carrollton. Yoakum negotiated trackage rights on

the Cotton Belt to allow Frisco trains to reach Fort Worth from Carrollton. The

connecting point in Fort Worth was Frisco Junction, about a half mile south of

Tower 60 where the Cotton Belt intersected a new 4.5-mile Frisco track that led

to a new yard in south Fort Worth that had been opened along the FW&RG main line.

Frisco Junction was very close to the stockyards, which Frisco served with

industry spurs.

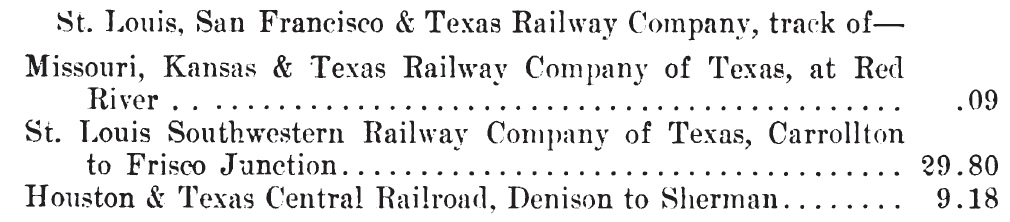

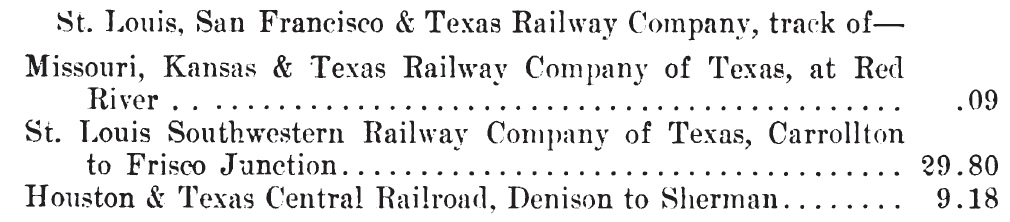

Above: RCT's 1907

Annual Report published at the end of the year listed Frisco's trackage rights,

all of which pertained to the line from the Red River to Fort Worth. All of

these rights had been in place since 1902.

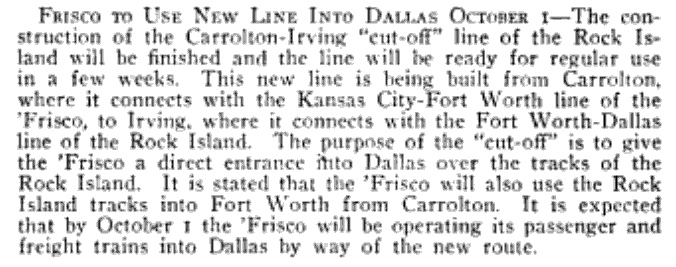

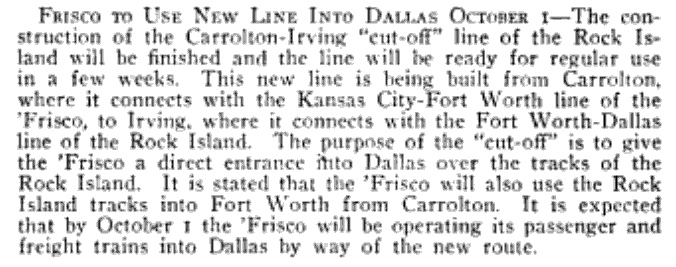

Yoakum's

strategic plan was to connect his Frisco and Rock Island operations in north

Texas with his Gulf Coast Lines network which was under development between New

Orleans and Brownsville. His next step was to have Rock Island

build a line from Fort Worth to Dallas; this was the genesis of the CRI&G

charter with a plan was to continue beyond

Dallas to reach the Gulf Coast Lines at

Houston. The track to

Dallas was laid in 1903, passing through Irving, eleven miles south

of Carrollton. After a four year delay, Rock Island built a "cut-off" between

Carrollton and Irving in late 1907 to allow Frisco trains at Carrollton to continue

south to Irving and proceed east to Dallas or west to Fort Worth on Rock

Island's tracks. This allowed Frisco to relinquish rights on the Cotton Belt from Carrollton to Frisco Junction.

Yoakum's

strategic plan was to connect his Frisco and Rock Island operations in north

Texas with his Gulf Coast Lines network which was under development between New

Orleans and Brownsville. His next step was to have Rock Island

build a line from Fort Worth to Dallas; this was the genesis of the CRI&G

charter with a plan was to continue beyond

Dallas to reach the Gulf Coast Lines at

Houston. The track to

Dallas was laid in 1903, passing through Irving, eleven miles south

of Carrollton. After a four year delay, Rock Island built a "cut-off" between

Carrollton and Irving in late 1907 to allow Frisco trains at Carrollton to continue

south to Irving and proceed east to Dallas or west to Fort Worth on Rock

Island's tracks. This allowed Frisco to relinquish rights on the Cotton Belt from Carrollton to Frisco Junction.

Right:

Railway World, August 23, 1907

Frisco trains entering Fort Worth from the east on Rock Island tracks curved

into downtown and connected into the T&P. This allowed trains to serve

passenger operations at the T&P Station, or proceed to the FW&RG tracks farther

west which led to the Frisco's freight yard. RCT's 1911 Annual Report lists Rock Island

with 0.36 miles of trackage rights on the T&P to effect this connection.

In 1937, Frisco sold the FW&RG to Santa Fe, but

retained the tracks going north from their main yard in south Fort Worth to

Frisco Junction. This allowed them to continue serving the stockyards. They also

retained the line between the yard and the T&P connection to facilitate

continued access via Rock Island's line from Irving. Although the line to Frisco

Junction crossed the T&P, it was not at grade and there were no connecting

tracks, hence the track between the yard and the T&P connection was critical.

At some undetermined date, this track was abandoned, leaving the line

to Frisco Junction as the only means for trains to reach Frisco's yard. Frisco

trains from Irving would enter

Fort Worth near downtown, but there was no direct route to the Frisco yard. Going north to Tower 60 was not a solution because

there was no simple way to turn the train around to go back south to Frisco Junction.

To solve this problem, a connecting track between the Rock Island and Cotton Belt

tracks was built south of Tower 60, barely north of their respective rail

bridges over the West Fork of the Trinity River. This required the Frisco to

obtain Cotton Belt rights over a short section of track.

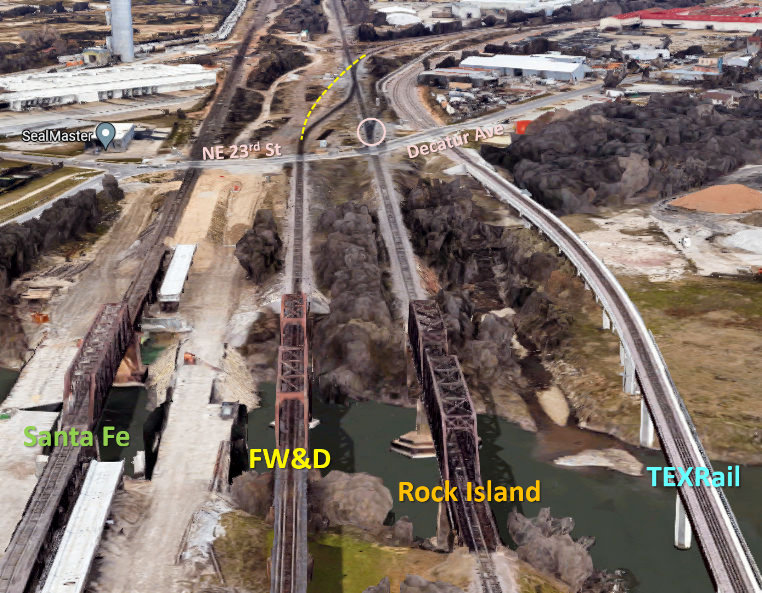

Below: In these two

north-facing aerial images ((c)historicaerials.com), the first four numbered

bridges, all of which cross the West Fork of the Trinity River, are: (1) Samuels

Ave. street bridge; (2) GC&SF rail bridge; (3) FW&D rail bridge; and (4) Rock

Island rail bridge. Bridge (5) is the Cotton Belt rail bridge over Marine Creek.

The rail connector (yellow arrows) that was added between 1952 and 1956 provided

a connection between the Cotton Belt track (green circle) and the Rock Island

(red circle). Frisco Junction was located about 700 ft. south of the Cotton Belt

bridge (5). Due to its proximity, Tower 60 would most likely have managed the

signals and switches for this connecting track. The red-dashed roadway is NE

23rd St. / Decatur Ave. which crossed the three main tracks at grade.

Below: Lines in the Samuels Ave. pavement mark its grade

crossing of the former Frisco connecting track; it was removed sometime between

1981 and 1990. Note also the swing gate to the right.

The switch off the Cotton Belt remains intact, but the track now ends inside the

fenced yard of the unidentified business to the right. (Google Street View 2013)

Below: The brick Tower

60 was razed

in the 1980s. (undated photo, Museum of the American

Railroad collection)

|

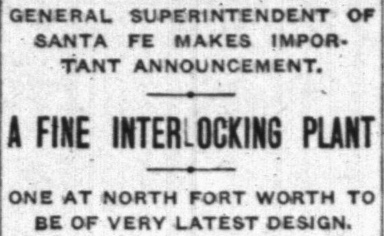

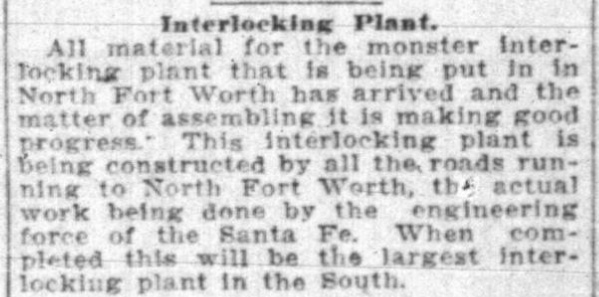

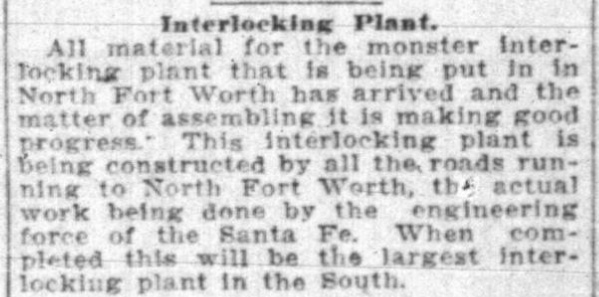

Fort Worth Record & Register,

February 8, 1904

Who wouldn't want to see a "monster interlocking plant"?

Fort Worth Record & Register,

September 2, 1904

|

|

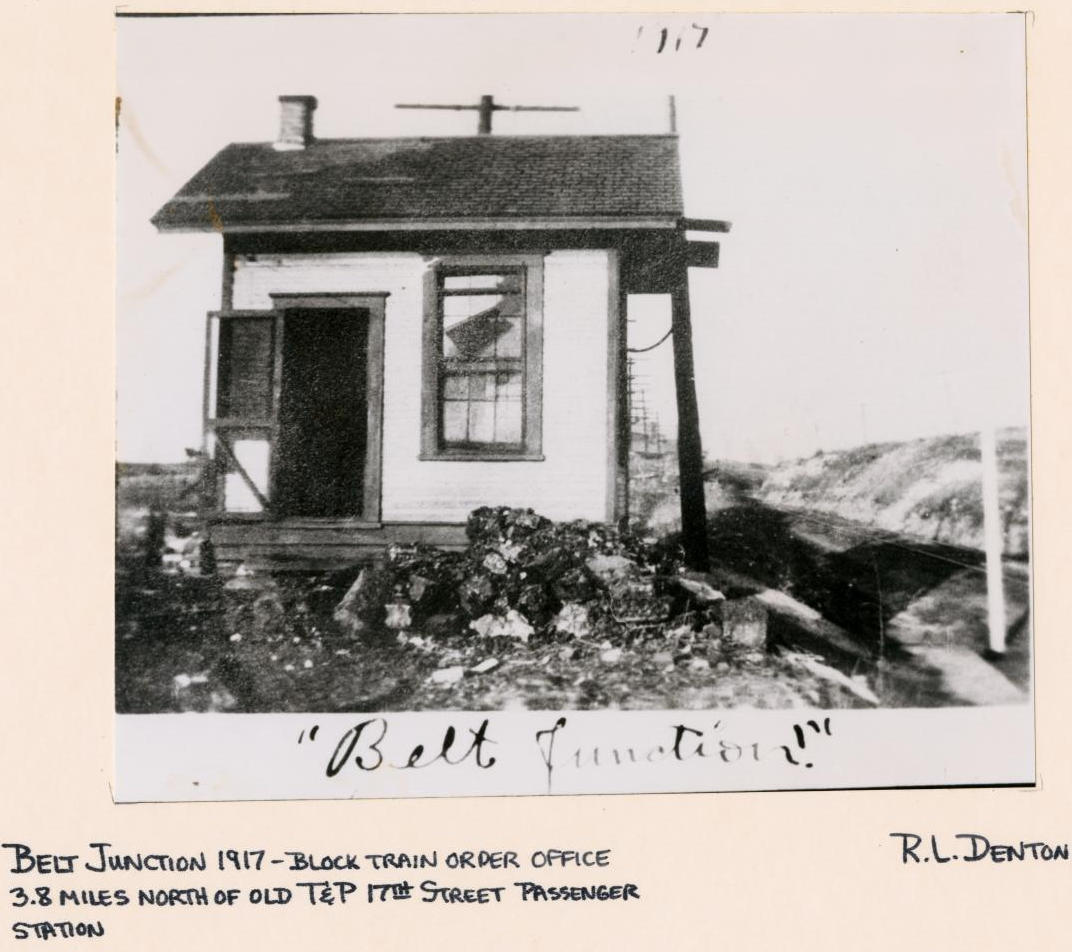

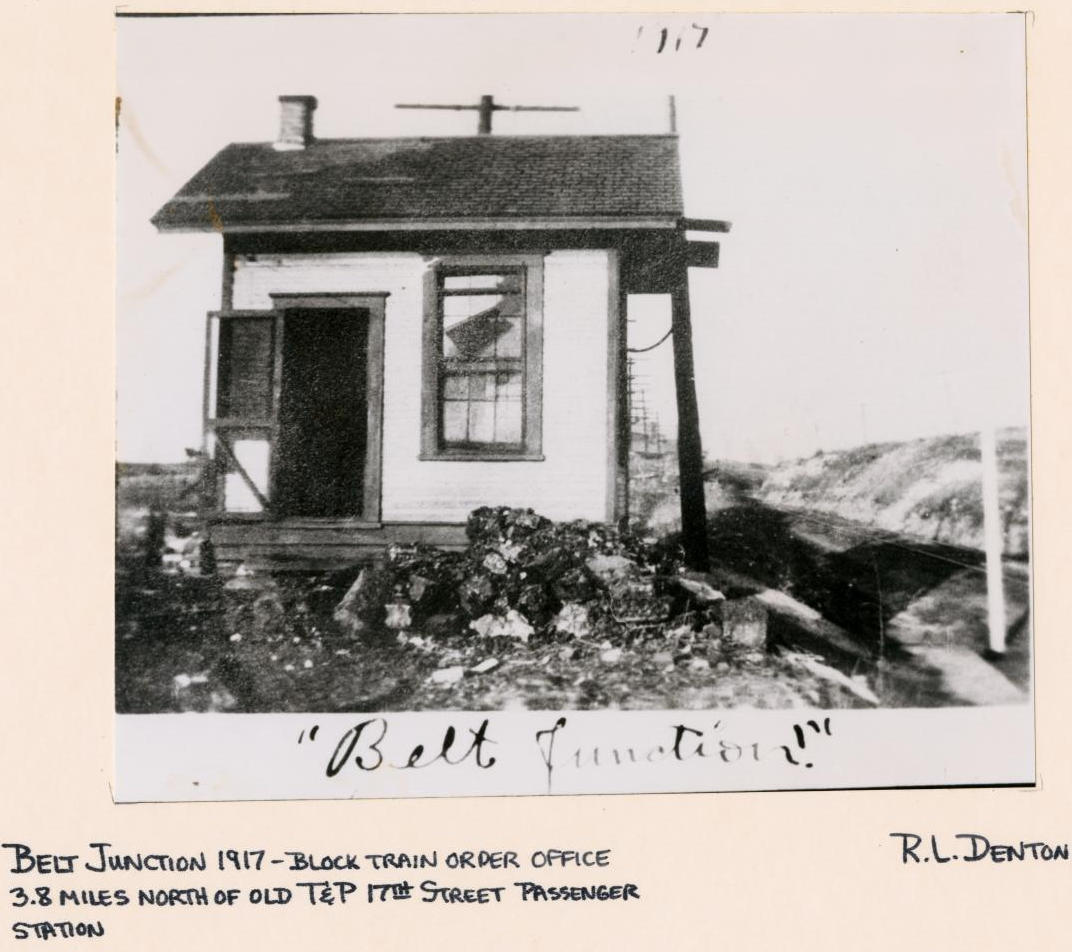

Left:

A train order office, presumably operated by the Fort Worth Belt, was

located at Belt Junction. (1917 photograph by R. L. Denton, courtesy the Grace

Museum, Cleburne, and The Portal to Texas History, hat tip, Dennis Hogan)

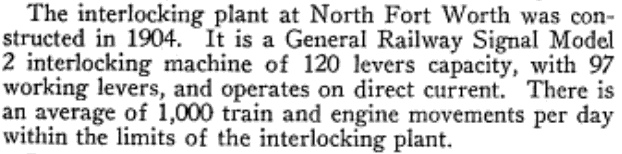

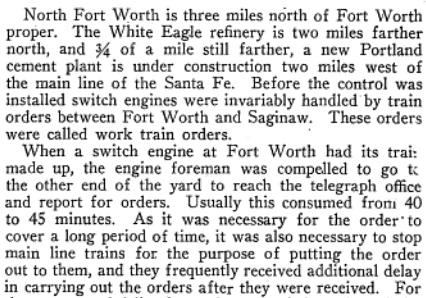

Right: These passages are excerpted from the June

6, 1925 issue of

Railway Review which published a

paper presented in March of that year by Santa Fe Signal Engineer, E. Hanson, at a Chicago gathering of the Signal Section of the American

Railway Association. The paper was titled Train Operation By Signal

Indication Only, describing a comprehensive control system that had

been installed

by Santa Fe between downtown Fort Worth and Saginaw, a distance of eight

miles. The control system allowed switch engines to operate without

train orders and was managed primarily by operators at Tower 60, near

the midpoint of the system. The paper notes "...an average of 1,000

train and engine movements per day..." through the Tower 60

interlocking. Wow! |

|

At the end of 1923, RCT's annual report changed

Tower 18's location from Joint Track to "North Fort Worth"

which had always been the location listed for Tower 60. While this

change

could

indicate that the Tower 18 controls were

remoted to Tower 60, T&P's 1925 List of Stations reported a telegraph at "StLSW

crossing" implying that Tower 18 was still manned. RCT had been known to change

tower location identity (e.g. Tower 28, which

started out at "Sulphur" and successively became "South of Texarkana",

"Texarkana, 2 miles west" and "West of Texarkana"), but such

descriptive changes usually occurred relatively soon after initial commissioning. The incentive to

change

Tower 18's location twenty years after commissioning isn't apparent unless it pertained to

operations, but using "North Fort Worth" had the downside of potential confusion

with Tower 60. RCT's interlocker list published December 31, 1927 changed Tower 18's

location again, this time to "North Fort Worth (Hodge)". This could imply that the interlocker controls were relocated to an office at Hodge

Yard, as the name would otherwise appear inapplicable to a crossing two miles

distant from both of the places known to railroaders as "Hodge". Certainly Hodge

Yard needed close coordination with movements through Tower 18, but whether

this entailed remote control of the interlocker (a technology becoming more

widespread

in the 1920s, see Tower 25) has not been determined. If the

controls were remoted to Hodge Yard in 1927, the interlocking plant was

presumably moved to an equipment cabinet so the tower could be closed.

Undoubtedly it was closed by the time the new automatic

interlocking plant was installed in 1931. The timing of Tower 18's demise and

the ultimate disposition of its building remains undetermined,

and no photo of the tower has been found.

Above: In this snippet from an undated (~ 1930s/40s)

aerial view of the meat-packing plants facing southeast, Tower 60 is highlighted left of center.

While the illuminated side of the tower certainly appears brighter than the

darker brick in more recent photos, and the respective brightness levels of the

roof and the tower's long side show a substantial difference compared to later years, this

could be simply a function of the sun's position and the angle of the light

reflected to the camera. Without more, whether this was an

earlier version of Tower 60 can't be established. Also, note the linear offset of the tower with

respect to the (white) outbuilding beside it. The exact same offset appears in

the image below left. It seems implausible that the new

brick tower would have been built in precisely the same spot as an older one

given the need to maintain operations during construction. It also seems likely

that if there was a consensus that the original tower needed to be replaced, the

effort to do so would have occurred sooner than perhaps 40 years after it opened.

There are numerous historic aerial images of the stockyards area showing Tower

60. Unfortunately, none of the ones found thus far provide sufficient resolution

to convey an unmistakable glimpse of a tower that preceded the brick structure

of later years. While there is valid speculation that the brick building was not

the first Tower 60, evidence of a prior tower remains elusive. Note also

that the NE 23rd St. / Decatur Ave. roadway is visible crossing all three tracks

at grade at upper right. The four bridges (Samuels Ave. plus the three rail lines) over

the West Fork of the Trinity River are visible beyond the road crossing, and the

Frisco connecting track does not yet exist. (image courtesy Bennett.Partners)

Above Left: This view looks northwest along the Rock

Island tracks passing beside the east face of Tower 60. The FW&DC crosses in the foreground

and the Fort Worth Belt is visible behind the tower. Above Right:

This southwest view down the Cotton Belt shows

southbound Santa Fe locomotives about to pass the west side of the tower. The near diamond is the Rock Island

crossing the Cotton Belt, and the Fort Worth Belt crosses the Cotton Belt just beyond it.

(both photos by Gary Morris, October, 1976)

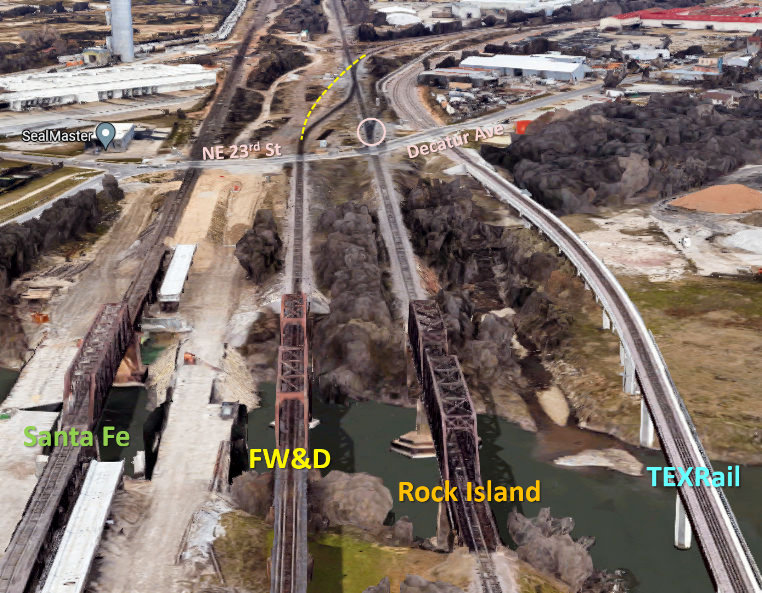

These recent Google Maps

simulated 3-D images of the Tower 60 junction have annotations showing the legacy

railroads.

Above: This view is northwest along

UP's ex-Rock Island right-of-way, similar to

the previous photo above left. Historic aerial images indicate that the "road" visible to

the left of the tower's foundation was originally a spur or connecting track. Aerial imagery shows that the Fort Worth Belt tracks were removed at

some undetermined time between 1981 and 2001.

Below: This image shows a southwest view along the former Cotton Belt tracks.

Majority ownership of the Fort Worth Belt was obtained

by the T&P in 1932, but the FWB continued to operate under its own name. In the

1970s, the FWB and T&P were merged into MP.

It had owned a majority share

of the T&P's stock since the 1930s, but did not effect control until 1976. MP

was acquired by UP in 1982 but it continued to operate under the MP name and it

proceeded to acquire and merge the Katy in 1988. SP had owned the Cotton Belt since 1932 and it

integrated the Cotton Belt operationally in 1992. In 1996, UP acquired SP and in

1997, all of its component railroads were integrated under the UP name.

In 1965,

the GC&SF was operationally merged into the parent AT&SF and the GC&SF name was

retired. In 1981, the C&S was merged into Burlington Northern (BN), taking with

it the FW&D, which ceased operations under that name. AT&SF and BN merged to

become Burlington Northern

Santa Fe (BNSF) in 1996.

The original track segment between Hodge Junction and Hodge remains in place with a few spurs into various trackside businesses.

It is owned and operated by

the Fort Worth & Western (FWW) Railroad, a Class III short-line railroad founded

in 1988 that also operates the yard at Hodge. Among various expansions, the FWW took

over operation of the former Cotton Belt line between Carrollton and Fort Worth.

Above: In these photos taken c.2002, a walk-in hut

located within the acute angle southwest of the diamond houses the automatic interlocker

at the Tower 18 crossing. The post in

front of the door holds manual override controls for UP and FWW to allow train

crews to override the signals when necessary. The odd curves on the FWW

(ex-Cotton Belt) track near the diamond resulted from the use of a

replacement crossing diamond that did not have the proper angle. This was

subsequently corrected. (Jim King photos.)

Above: This 2022 Google Earth image of the Tower 18

crossing shows a connecting track in the northwest quadrant. It also shows a

rail bridge passing over Old Denton Rd. and the former Joint Track.

TEXRail, a commuter rail system between downtown

Fort Worth and DFW airport, was constructed sharing portions of the former Cotton

Belt tracks and right-of-way. The FWW freight tracks are visible parallel to the

bridge, still crossing the former Joint Track (now UP) at grade. Just over a

mile to the east, the commuter and freight tracks merge into a single

ground-level track. Proceeding east to Grapevine and DFW Airport, they

periodically re-divide into separate commuter and freight tracks in the vicinity

of passenger stations. To the west, the commuter tracks remain isolated all the

way into downtown, and much of the right-of-way is grade-separated.

Kal Silverberg explains the

connecting track... (Sept. 22, 2004)

"Tower 18 now has a connection in place in the northwest quadrant so southbound

trains on the former T&P can go west on the former SSW through Hodge Yard. There

is a new track along the north side of Hodge Yard and it has CTC signals at the

east end of Hodge Yard (by Sylvania St. crossing) waiting to be turned on. The

new track ties into the former FW&D line just east of Deen Road. It is my

understanding that UP will run directionally between Towers 18 and 55."

Kal Silverberg discusses the commuter rail bridge... (June 4, 2020)

"TEXRail to DFW Airport from the T&P station in downtown Fort Worth began

operations in January, 2019. Construction probably started in 2017 so that's

when the bridge over Tower 18 went in. TEXRail is completely separated from the

railroad network from north of Tower 18 to the former 6th Street Jct. in Fort

Worth, with the exception of one crossover at the north (east) end of Hodge Yard

to enable equipment to get to and from the TEXRail maintenance base."

Above:

Facing east-northeast along the former Cotton Belt right-of-way, this February

2019 Google Street View shows the Tower 18 crossing site. The former

Joint Track, now a UP main line, crosses in the foreground, and UP's 2004 connector track in the northwest quadrant is

visible at far left.

Overhead, the TEXRail bridge provides grade separation for commuter rail trains

to/from DFW airport. The freight rails and the commuter rails join into a single

ground-level track just over a mile distant, but they periodically separate at

commuter stations as the line proceeds to DFW Airport.

Below:

This simulated Google Maps 3-D aerial view of Hodge Yard shows how the Cotton Belt would

have crossed the FW&DC main line

from Hodge Jct. prior to the FW&DC's construction of a separate line into downtown (curved line

at far left). Now, the

track coming up from Hodge Jct. splits into east and west connector tracks, the

west track showing a pair of UP locomotives. The blue arrows mark the elevated

line for TEXRail commuter trains which returns to ground level to pass beneath

Interstate 35.

|

Left:

Looking north toward the former Tower 60 crossing, this Google Maps simulated 3-D image

shows that the traditional "Three Sisters" rail bridges over the West Fork of the Trinity River

have been joined by a fourth at far right carrying TEXRail commuter trains.

Where the FW&DC (now BNSF) previously curved northeast (yellow

dashes) to cross the Rock Island (now UP), the diamond has been removed,

replaced by two switches and a short track segment on the Rock Island.

Taking the north switch, the track immediately crosses over the Cotton

Belt (now FWW) with no connection. Instead, a switch (pink circle) off

the Rock Island just beyond the Decatur Ave. grade crossing leads to the Cotton Belt tracks,

which proceed northeast into Hodge. Although the Cotton Belt and FW&DC

tracks are generally parallel between Tower 60 and Hodge, there is no crossover

between them until reaching the west end of the yard.

Above: The former

Joint Track (now UP) bridge over the West Fork of the Trinity River is

0.6 miles east of the "Three Sisters".

(Google Street View, January, 2023) |

Another

railroad that operated through Tower 60 at various times was the St. Louis, San

Francisco & Texas, a subsidiary of the St. Louis & San Francisco ("Frisco")

Railway, a major Midwest railroad. In

the early 1900s, the Frisco and Rock

Island railroads were led jointly by B. F. Yoakum, a native Texan who had risen to

the top after executive stints with the San Antonio &

Aransas Pass Railway and the GC&SF. Yoakum was an expert in Texas

railroading, and he sought to expand the networks of the Frisco and Rock Island

in state. To compete against Santa Fe for livestock shipments from the vast

range southwest of Fort Worth, the Frisco purchased controlling interest in the Fort Worth & Rio Grande

(FW&RG) Railway in 1901. It had tracks from Brownwood to Fort Worth, a shorter,

direct line compared to Santa Fe's route from Brownwood via

Another

railroad that operated through Tower 60 at various times was the St. Louis, San

Francisco & Texas, a subsidiary of the St. Louis & San Francisco ("Frisco")

Railway, a major Midwest railroad. In

the early 1900s, the Frisco and Rock

Island railroads were led jointly by B. F. Yoakum, a native Texan who had risen to

the top after executive stints with the San Antonio &

Aransas Pass Railway and the GC&SF. Yoakum was an expert in Texas

railroading, and he sought to expand the networks of the Frisco and Rock Island

in state. To compete against Santa Fe for livestock shipments from the vast

range southwest of Fort Worth, the Frisco purchased controlling interest in the Fort Worth & Rio Grande

(FW&RG) Railway in 1901. It had tracks from Brownwood to Fort Worth, a shorter,

direct line compared to Santa Fe's route from Brownwood via

Yoakum's

strategic plan was to connect his Frisco and Rock Island operations in north

Texas with his Gulf Coast Lines network which was under development between New

Orleans and Brownsville. His next step was to have Rock Island

build a line from Fort Worth to Dallas; this was the genesis of the CRI&G

charter with a plan was t

Yoakum's

strategic plan was to connect his Frisco and Rock Island operations in north

Texas with his Gulf Coast Lines network which was under development between New

Orleans and Brownsville. His next step was to have Rock Island

build a line from Fort Worth to Dallas; this was the genesis of the CRI&G

charter with a plan was t