Texas Railroad History - Tower 82 - San Angelo

A Crossing of the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe Railway and the

Kansas City, Mexico & Orient Railroad

Above: This undated photo of Tower 82 from the Robert E.

Pounds collection appears in the book The Orient,

by Robert E. Pounds, John B. McCall and John R. Signor, published in 2011 by the

Santa Fe Railway Historical & Modeling Society, Midwest City, OK (hat tip, Todd

Minsk.) The tower was located southeast of the diamond, and the camera is facing

generally in the direction of San Angelo. Sources differ on the precise

timeframe of construction, but it was sometime around 1910, and this photo could

easily be of railroad or construction management viewing the newly built tower.

|

Left:

This north-facing drone image shows the former crossing

of the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe (GC&SF) Railway and the Kansas City, Mexico &

Orient (KCM&O) Railway on the north side of San Angelo. The crossing was

interlocked as Tower 82 in the numbering system of the Railroad Commission of

Texas (RCT). There is no longer a diamond here; the north / south former KCM&O tracks

are continuous while the former GC&SF rails connect into it from the northeast and

southwest, but no longer cross.

The tracks to the north reach a yard and

a rail park, but are abandoned beyond E. 50th St., just over two miles from the junction. To the southwest,

the tracks end in a half mile, serving a business on the south side of Culwell

St. The other two directions from the crossing extend beyond San Angelo to

connect to the national rail network. To the northeast, the line connects to the

Burlington Northern Santa Fe main line at San Angelo Junction, five miles

southeast of Coleman. The line south turns southwest to Fort Stockton,

continuing to Alpine where it connects to Union Pacific's Sunset Route. (photo by Miguel O, 2017) |

The Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe (GC&SF) Railway started

construction in 1875 with a long term plan to reach New Mexico and Colorado.

After various financial issues were resolved with a brief bankruptcy in 1879,

their main line construction from Galveston reached Lampasas

in 1882. The end of track remained there for a couple of years while the company

did construction work elsewhere, mainly

branches off the main line into east Texas and Houston.

In 1885, construction resumed northwest from Lampasas, completing 71 miles to Brownwood in

December. The question on the minds of west Texans was...where precisely was this

northwestern main line headed?

The Taylor County News, June 5, 1885

The Taylor County News, June 19, 1885 |

The Taylor County News kept close

tabs on the GC&SF's northwest progress virtually every week in the

spring and summer of 1885, regurgitating rumors fed by passing travelers

claiming to have inside information about the GC&SF's plans. As an

Abilene weekly, every Friday's newspaper reflected bona fide hometown

optimism that the main line would be coming to

Abilene.

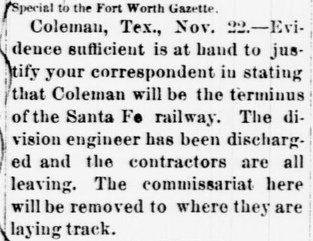

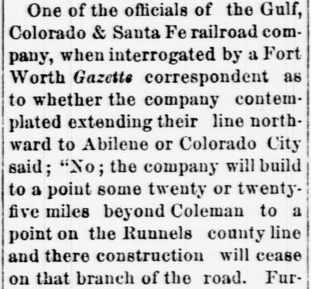

Left:

The Taylor County News of November

27, 1885, quotes a Fort Worth Gazette

report that the main line has terminated at Coleman, and that the

"commissariat" was being redeployed. The location "where they are laying

track" was a westward line that branched off the main track near

Coleman.

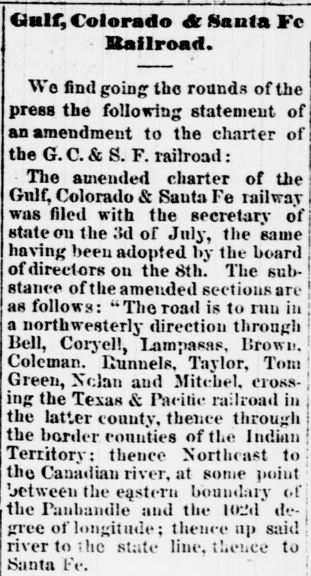

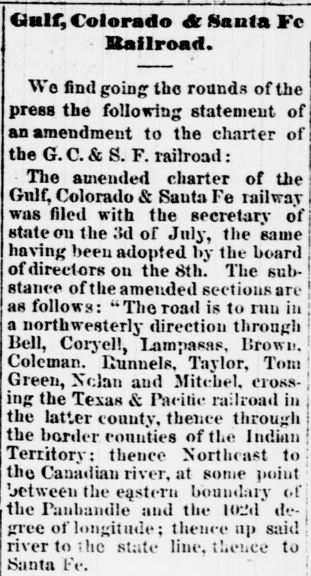

GC&SF historian William Osborn describes the charter amendment

that was filed by the GC&SF early in the summer of 1885.

...there was debate within the company regarding the best destination

for its westward terminus...[T]he charter was amended to provide for a

change of route west of Temple, routing through the counties of Bell,

Coryell, Lampasas, Brown, Coleman, Runnels, Taylor, Tom Green, Nolan and

Mitchell, forming a junction there with the Texas & Pacific Railway. Jay

Gould’s Texas & Pacific line between Fort Worth and El Paso had been

completed in 1881... |

The Taylor County News, June 25, 1885 |

The GC&SF amended their charter in the summer of 1885,

and it included a list of counties to which they expected to build. By July,

1885, the GC&SF had already built through Bell County (Temple, Belton, Killeen),

Coryell County (Copperas Cove) and Lampasas County (Lampasas.) From Lampasas,

they had continued into Brown County at Goldthwaite, a town that would become

the seat of Mills County when that county

was carved out of surrounding neighbors two years later. From Goldthwaite, tracks

would reach Brownwood in December, 1885. Beyond Brownwood, the details were

vague with six additional counties listed: Coleman (Coleman), Runnels

(Runnels City), Taylor (Abilene), Tom Green (San Angelo), Nolan (Sweetwater) and

Mitchell (Colorado City.) Three of these, Taylor, Nolan and Mitchell, were

east / west neighbors through which the Texas & Pacific (T&P) Railway passed, but

the T&P was about fifty miles north of Brownwood. The

charter amendment specifically cited Mitchell County as the crossing point of

the T&P, so listing all three counties left people wondering if the GC&SF

planned to parallel the T&P between Abilene and Colorado City, an idea that made

no sense. The

other three counties were east / west neighbors generally aligned with, and west

of, Brown County. Coleman County was due west of Brownwood and undoubtedly would

be next for construction. From the town of Coleman, there was an obvious route

north to Abilene in Taylor County and there was a feasible alternative through

Runnels County into Nolan and Mitchell counties. Tom Green County (San Angelo) was

the apparent outlier sitting mostly southwest of Runnels County. There was

literally no sane way to build to all of these counties without a branch line

somewhere. If a branch was being considered, the details were unknown,

or at least undisclosed.

There would indeed be a branch line that would

go west toward San Angelo. After it was

built, it was treated as the main line for more than two decades because the

"real" main line to the northwest had stopped at Coleman, five miles

beyond the branch point for San Angelo. With the future main

line merely a 5-mile stub to Coleman, the connection of the main and branch

lines became known as Coleman Junction. Santa Fe subsidiary Pecos &

Northern Texas (P&NT) finally completed the northwest main line between Coleman

and Slaton in 1911.

|

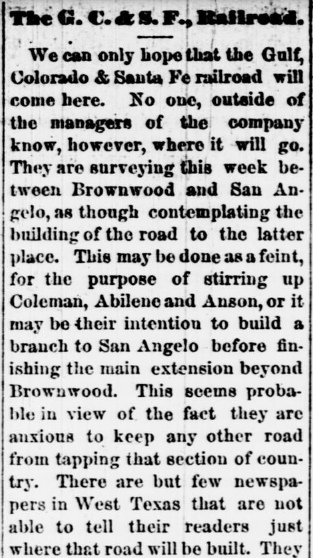

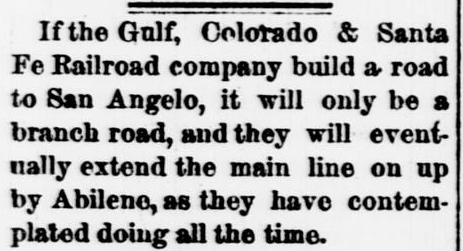

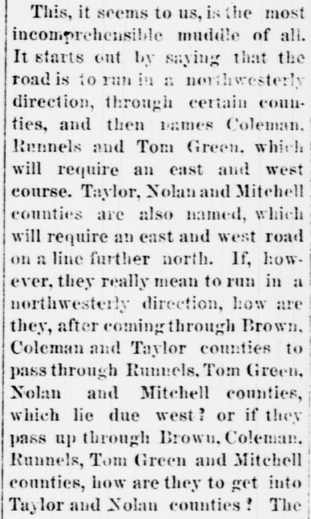

The Taylor County News of July 24, 1885 (left

and right) reported on the details of the amended

charter filed by the GC&SF, charitably calling it "the most

incomprehensible muddle of all." Earlier (below

left, July 3, 1885) the same newspaper had

hypothesized that if the GC&SF built to San Angelo, it would only be a

branch line, because, of course, the main line would still come to

Abilene! They were half right. The semi-official bad news soon arrived (below

right, The Taylor County News,

October 30, 1885); the

extension toward Abilene would stop a few miles beyond Coleman, at least for

a few years (and it would actually end within the town of

Coleman, not beyond it.)

Construction northwest of Coleman didn't resume until 1911 when the P&NT

built 183 miles to Slaton. There it connected with Santa Fe's network to

New Mexico and California. Eventually, the tracks through Coleman came

to be considered the main line, so Coleman Junction was renamed "San

Angelo Junction". The P&NT tracks passed no closer than eleven miles

from downtown Abilene, going through nearby Buffalo Gap instead. (Editor's Note: It is

not true that building through Buffalo Gap was intended to capitalize on passengers'

desire

to enjoy

the world's

greatest Jalapeno Cheesecake! ...hat tip, Jimmy Barlow. The purveyor,

Perini Ranch Steakhouse,

was not established until 1983, but your Editor can confirm that this

would have provided a legitimate reason to build through Buffalo Gap.)

|

|

|

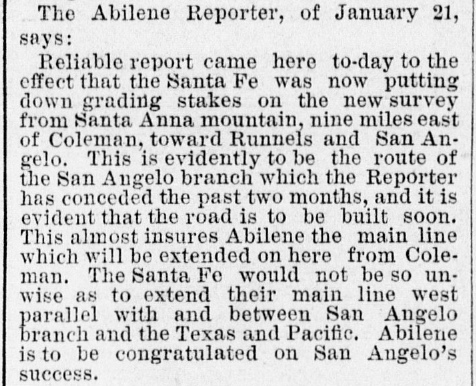

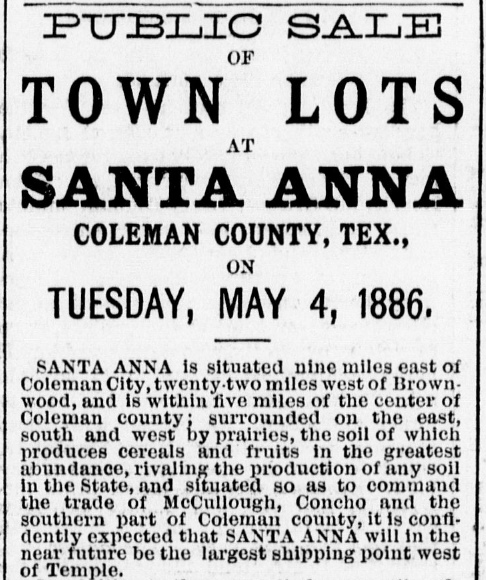

Left: The

Galveston Daily News of January 25, 1886 quotes a story from

the Abilene Reporter that

again was half right. There was indeed a branch line being planned

toward Runnels and San Angelo. The branch point off the main line would

be Coleman Junction five miles east of Coleman. The location "nine miles east"

of Coleman was where the new town of Santa Anna would be founded, as advertised in the Galveston Daily News of

April 19, 1886 (right). The optimism of the

Abilene Reporter ("This almost

insures Abilene the main line...") would not be rewarded, however,

despite their self-congratulation. When the extension was actually

built, it bypassed Abilene eleven miles southwest and crossed the T&P a few miles east of

Sweetwater in Nolan County, 33 miles west

of Abilene. The crossing was 34 miles east of Colorado City, seat of Mitchell

County where the junction had been projected in the GC&SF's amended charter.

Below:

The Taylor County News of

Friday, March 12, 1886 reported that the first passenger train into

Coleman had arrived on March 7th.

|

|

West of Coleman Junction, the surveyed GC&SF

right-of-way to San Angelo crossed the Colorado River five miles south of

Runnels City, the seat of Runnels County. Though they tried their best

(including a direct appeal to GC&SF management in a meeting at Galveston), the 250

residents of

Runnels City could not convince the GC&SF to build through their town. Instead,

on the north bank of the Colorado River, the GC&SF founded a new town,

Ballinger, named for prominent Galveston attorney

and GC&SF stockholder William Ballinger. The tracks reached Ballinger in May or

June, and a public sale of town lots was held on June 29, 1886. Ballinger

remained the western terminus of the GC&SF for more than two years as their construction focus turned elsewhere.

In March,

1886, negotiations led by GC&SF President George Sealy

resulted in an agreement under which the much larger Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe

(AT&SF) Railway would acquire the GC&SF on favorable terms if the GC&SF

quickly completed three

construction projects. The GC&SF was able to lay three hundred

miles of track in one year to finish all of the projects, but none of them pertained to the northwest

extension. The acquisition proceeded as planned in 1887 and the GC&SF began

operating as a wholly-owned subsidiary of the AT&SF.

Construction

west from Ballinger across the Colorado River toward San Angelo, 36 miles away,

commenced in late May, 1888. A story in the Austin Weekly Statesman

of May 31, 1888 noted that

San Angelo's railroad committee was "...having some annoyance in

securing right-of-way and depot grounds..." which had been promised to the

railroad. The situation was no better at Ballinger. On the San Angelo side of the

Colorado River "...right-of-way has been purchased at the rate of $150 per

acre...about two miles from town, which could not have been sold for more than

$5 or $10 per acre." The planned route of the railroad beyond Ballinger was

known, hence land prices nearby had

skyrocketed. The first construction train was reported into San Angelo on August

6th, and Santa Fe officially accepted the line from the contractors in early

September.

|

San Angelo had been founded only twenty years earlier

when Fort Concho was established to help protect the frontier. The town

was settled where the North, South and Middle Concho Rivers joined,

providing a good water supply. Along with plenty of suitable pasture

land, it became the center of a vast ranching area. Hauling livestock was a

significant business for railroads, and San Angelo became one of the biggest livestock shipping points in

the country.

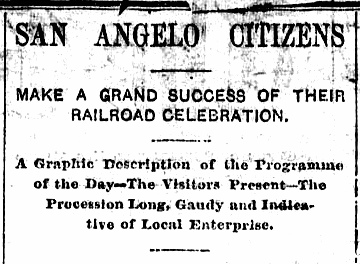

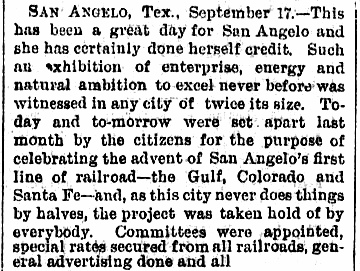

Left and

Right: San Angelo's citizens, perhaps all 2,000 of them,

celebrated the arrival of the GC&SF. The story conveys the "gaudy"

pageantry and palpable excitement of the residents of this isolated town upon finally

getting modern transportation to the outside world. (Galveston

Daily News, September 18, 1888) |

|

In 1891, the new town of Sterling City was founded

along the North Concho River about forty miles northwest of San Angelo. Despite

the distance, it was still in Tom Green County, so its citizens petitioned the

Legislature to carve out a new county so they could avoid the arduous eighty

mile round trip for county business. Although the Legislature granted the

request, San Angelo remained the major population center in the area, hence

Sterling City locals frequently needed to travel there for various goods and

services. In 1909, residents of Sterling City and elsewhere in the region

chartered the Concho, San Saba & Llano Valley (CSS&LV) Railroad. The plan was to

build in two directions out of San Angelo: northwest to Sterling City and

southeast to reach communities along the Concho River (Paint Rock), the San Saba River

(Menard) and the Llano River (Junction). The long term objective was to continue

beyond Sterling City to Lubbock.

Santa Fe agreed to finance the CSS&LV construction

and to provide trackage rights on the GC&SF between San Angelo and Miles, a

community midway between San Angelo and Ballinger. Miles became the branch

point for a 17-mile CSS&LV line to Paint Rock for which work began in

1909. Construction of a 43-mile line from San Angelo to Sterling City also

began in 1909.

Service commenced in August, 1910 and the CSS&LV was acquired by the AT&SF that

same month and leased to the GC&SF. There was no additional construction under

the CSS&LV charter. The Miles - Paint Rock branch lacked the revenue to sustain

it and was abandoned in 1937. The San Angelo - Sterling City segment lasted

longer, but was abandoned in 1959.

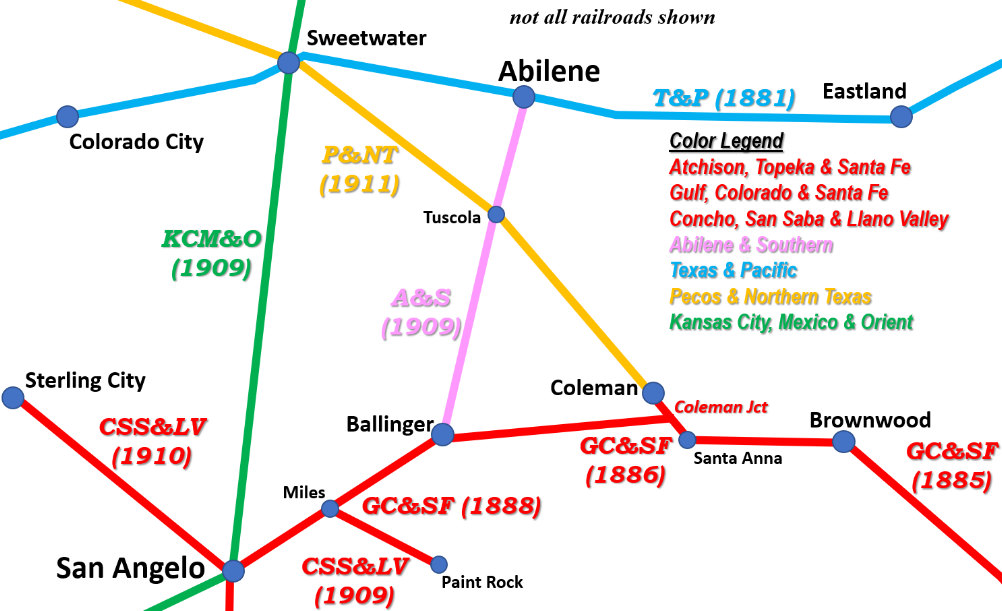

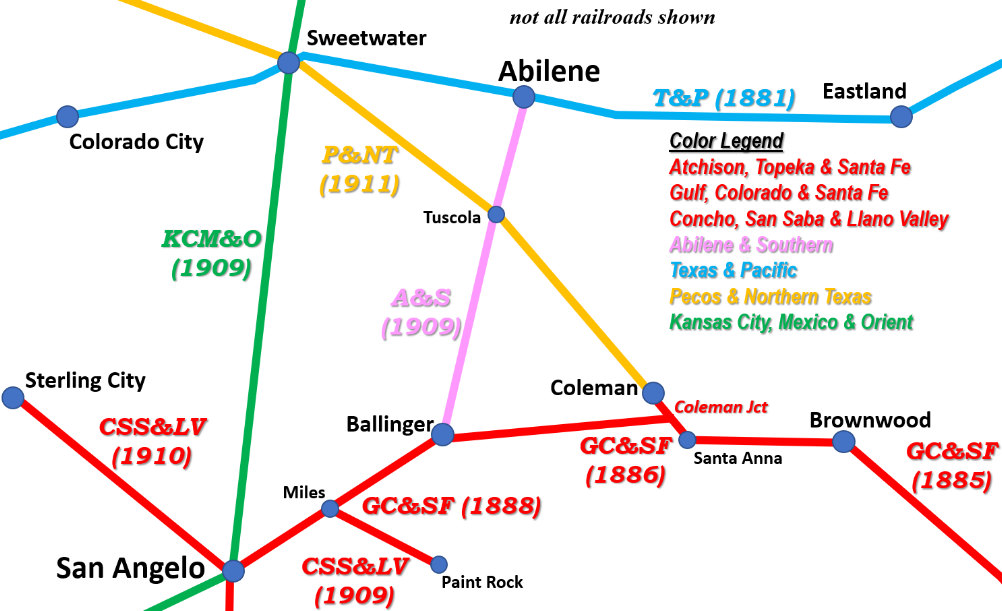

Right:

Railroads near San Angelo in the 1885 - 1912 timeframe

Texas & Pacific: The T&P served

Fort Worth and El Paso,

having built through Abilene in 1881.

Atchison,

Topeka & Santa Fe: The AT&SF acquired the GC&SF in 1887, and financed

the Concho, San Saba & Llano

Valley, buying it in 1910.

Abilene & Southern:

The original concept of an "Abilene & San Angelo" railroad was never

built. The A&S was built to Ballinger

in 1909 and became part of the T&P in 1926.

Pecos & Northern Texas: The P&NT was the

AT&SF subsidiary that built the northwest extension from

Coleman to Slaton in 1911. It crossed the A&S at Tuscola.

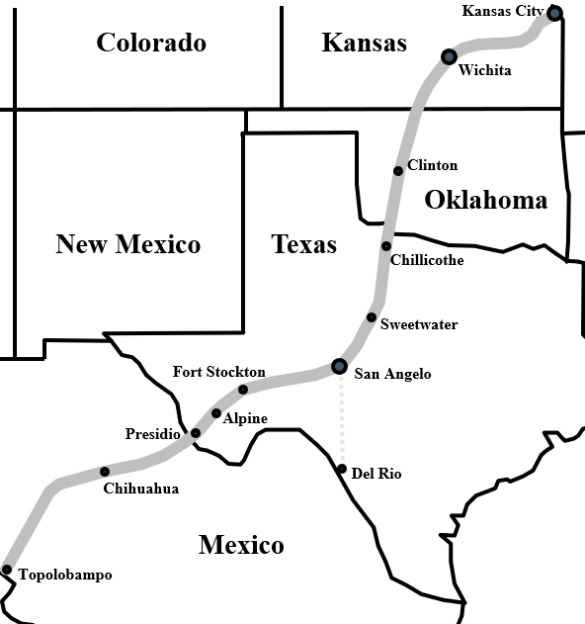

Kansas City, Mexico

& Orient: The KCM&O planned to build from Kansas City to Topolobampo,

Mexico on the Gulf of California as a short route to a Pacific

port. The line passed through San Angelo in 1909 - 1910. |

|

Santa Fe alone served San Angelo until a second

railroad arrived in 1909. It was the brainchild of Arthur Stilwell, a

New Yorker who had settled in Kansas City in 1886. As a railroad promoter,

Stilwell's concept for rails out of Kansas City was to find the shortest

route to the nearest deep water port. He first practiced this strategy when he founded the

Kansas City, Pittsburg and Gulf Railroad. The idea was simple; build due south

from Kansas City through Pittsburg (Kansas), Texarkana and

Beaumont to reach a

new port on the Gulf of Mexico that he named for himself,

Port Arthur, Texas.

The line commenced operation in late 1897, but when it went into foreclosure in

1899, Stilwell lost his investment and was booted off the management team. The company was financially

reorganized as the Kansas City Southern Railway, which remains a major railroad

today.

To say the least, Stilwell was unhappy with the banking interests that

had forced him out. His closest friends were concerned about his well-being, so to

cheer him up, they hosted a special dinner in his honor on February 10, 1900.

Stilwell gave a speech to the assembled guests, thanking them for the dinner and

their attendance. He then took the opportunity to unveil his newest plan: the

Kansas City, Mexico & Orient Railway.

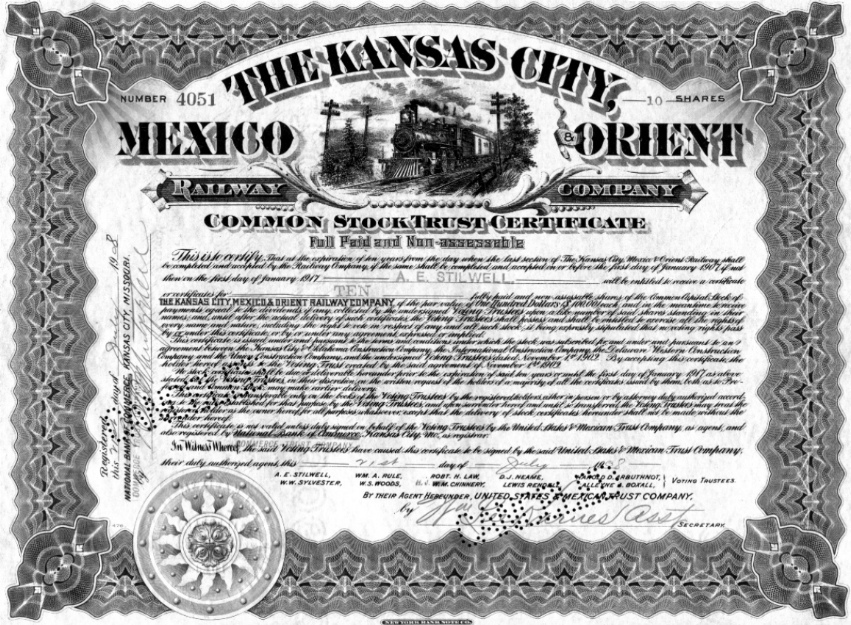

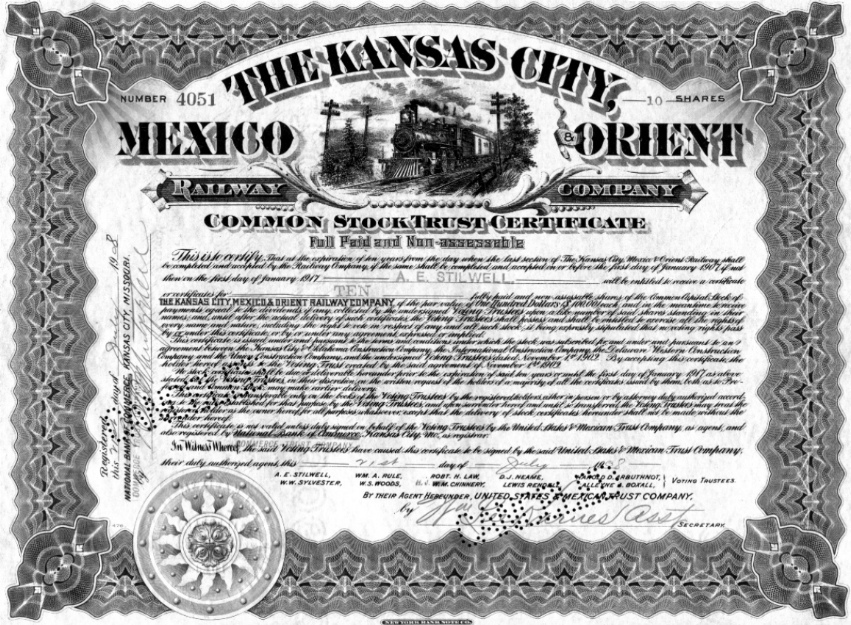

Above: KCM&O Railway ten share

common stock trust certificate issued to A. E. Stilwell on July 21, 1908

(Charles Alspach collection)

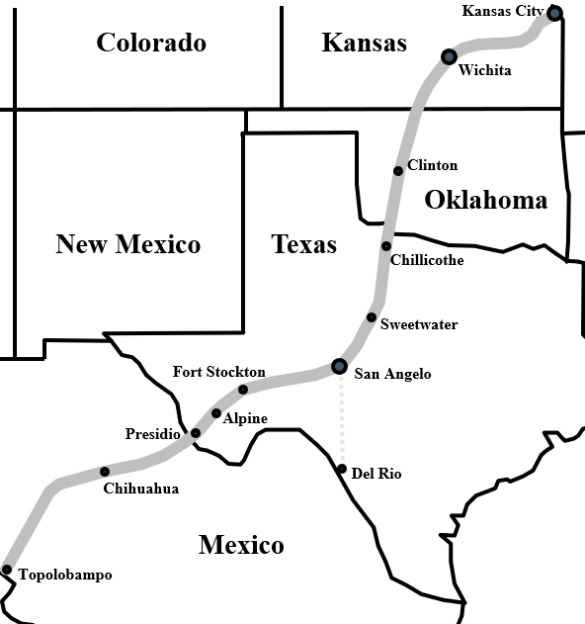

Left:

the route of the KCM&O from Kansas City to Topolobampo, Mexico

Turning his attention to the Pacific Ocean, Stilwell was following the same

script: build a rail line from Kansas City directly to the nearest deep water

port, which happened to be at Topolobampo, Mexico on the Gulf of California. The

estimated rail distance was approximately 400 miles shorter than the existing

route from Kansas City to California. Two months after the dinner, Stilwell

signed an agreement with the President of Mexico, Porfirio Diaz, wherein the

Mexican government agreed to subsidize the KCM&O's construction in that country

at the rate of $5,000 per mile. Diaz fully expected that the rail line's route through

an under-developed area of Mexico would facilitate access to

untapped mineral resources and timber lands.

Construction proceeded at

various locations in Mexico, Kansas and Oklahoma. In Kansas, Wichita became the north

end of the line instead of Kansas City until a connecting track segment could be

built. To comply with Texas' railroad laws, Stilwell would need a

separately chartered railroad headquartered in state. S. G. Reed, in his

definitive work A History of the Texas Railroads

(St. Clair Publishing, 1941), explains how Stilwell obtained one...

Stilwell, in a preliminary survey to determine the route through Texas,

discovered a little railroad which had been chartered in Texas on July 15, 1899,

as the Panhandle & Gulf Ry. to build from Sweetwater to San Angelo.

This little railroad had, also, been organized to take over another local

enterprise which had been chartered as the Colorado Valley Railroad Co.

to build between the same two cities, which already had seven miles completed

out of Sweetwater. Stilwell had the charter of the P. & G. amended on

March 3, 1900, to permit him to take it over under the name of the Kansas

City, Mexico & Orient Railway Co. of Texas and also to extend it to the Red

River on the north and the Rio Grande on the south.

This charter also

gave the right to build a branch line from San Angelo to Del Rio. As this road

would traverse a territory much of which was without railroad facilities and

would also strengthen those communities which already had them, such as

Sweetwater, San Angelo and Alpine, by enlarging their trade territory and

shortening the distance to markets, it was assisted by liberal donations. ...

The construction of the Texas line began at Sweetwater in 1904.

|

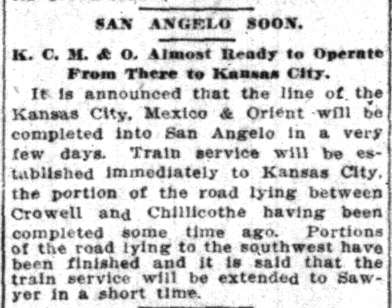

Building north from Sweetwater,

the KCM&O reached the Pease River in the fall of 1908. Crews working

south from Oklahoma crossed the Red River and reached the Pease shortly thereafter. Service between

Sweetwater and Wichita, Kansas began on January 31, 1909. Going south from Sweetwater, construction commenced in the spring of

1909 and reached San Angelo in September. The KCM&O was destined

for Alpine, so it made sense to build their San Angelo depot south of the

North Concho River, which ran through the middle of town. Santa Fe, with no plans to build farther south, had

erected their depot north of the

river.

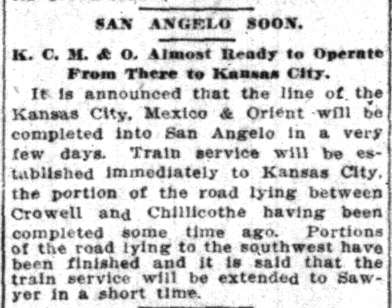

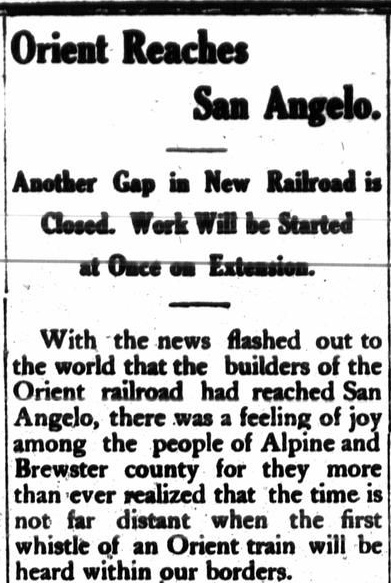

Left:

Fort Worth Record and Register,

Sept. 18, 1909 Right:

Alpine Avalanche, Sept.

23, 1909

Construction of the

KCM&O main line southwest from San Angelo toward Fort Stockton began in 1910;

the first 28 miles to Mertzon opened on March 31, 1911. A year later,

the KCM&O entered receivership and construction stopped until the

Receiver could take action. Work slowly resumed and the first passenger

train into Fort Stockton finally arrived in November, 1912. By then, most of the

grading to Alpine had been completed. Service to Alpine began in 1913

while the railroad remained in receivership. |

|

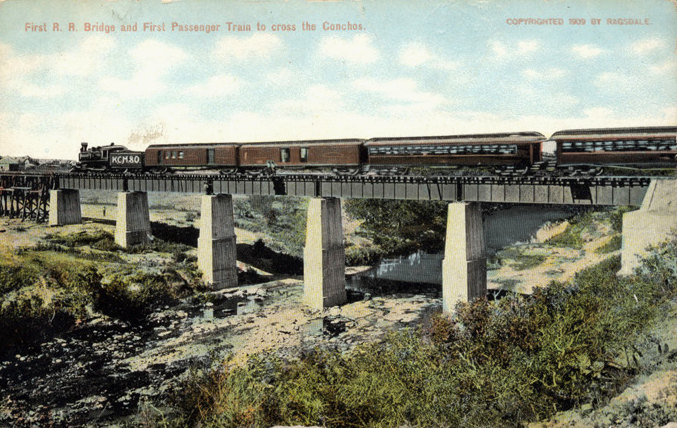

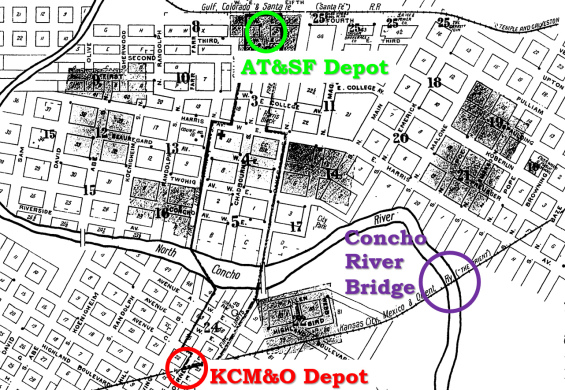

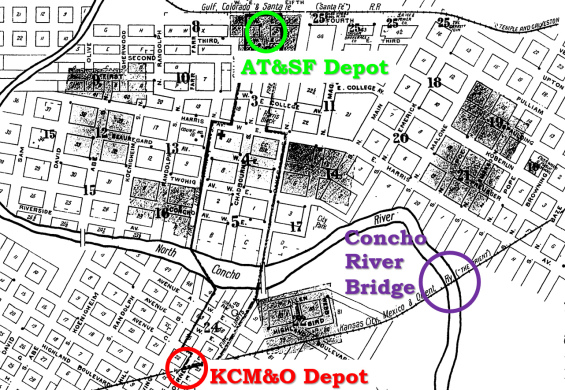

Above:

annotated Sanborn Fire Insurance Map of San Angelo, 1913

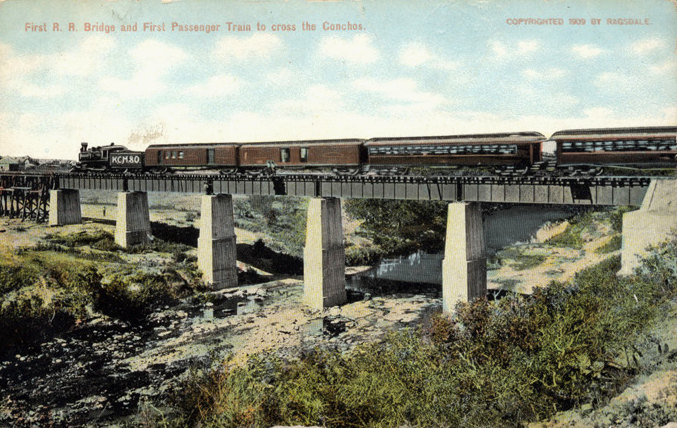

Left:

"First R. R. Bridge and First Passenger Train to cross the Conchos" ((c)

1909 M. C. Ragsdale, courtesy Texas Transportation Archive,

Murry Hammond

collection) |

|

The KCM&O's March, 1912 receivership is easily traced to a lack of local traffic

along the line. The KCM&O mostly ran through sparsely populated areas where

there simply wasn't enough commerce to sustain the enterprise. The original

idea of shipping from the Midwest to the Pacific port of Topolobampo could not

be executed until the track segment through Mexico was complete. Unfortunately

for the KCM&O, that would be in the distant future due to the difficulty of

building across Copper Canyon in Mexico.

Until there was a need for a rail bridge over the Rio Grande, the end of track

remained at Alpine where it connected into the Southern Pacific (SP) Sunset

Route. The Bankruptcy Court had authorized Receiver Certificates to fund the

remaining track-laying from Fort Stockton to Alpine under the theory that the SP

connection might generate sufficient traffic to bring the KCM&O into

profitability. The receivership ended in June, 1914, but the Alpine interchange

didn't make much of a difference in the railroad's overall financial situation,

and it went back into receivership in 1917.

|

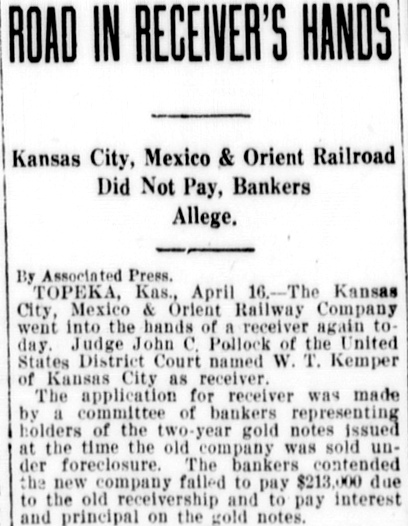

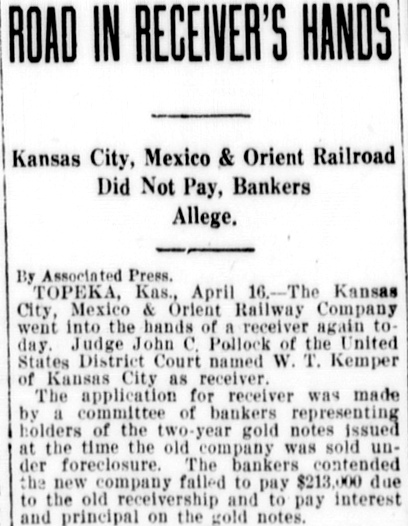

Left: The San

Antonio Express of April 17, 1917 reported that the KCM&O had

gone into receivership "again" with William T. Kemper, Sr. of Kansas

City named Receiver. Kemper was a well-known banker and the patriarch of

the Kemper family respected as major Kansas City benefactors.

Kemper signed a contract

with the U. S. Railroad Administration (USRA) in June, 1918, covering

KCM&O's participation in the USRA's national management of railroads

during World War I. Some creditors urged USRA to

cancel the contract so that Kemper could be forced to liquidate the

railroad's assets, but USRA refused. Even when control of the KCM&O

returned to Kemper after the War, he was able to keep the KCM&O alive just long enough to

get lucky; a major oil discovery in 1923 at Big Lake southwest of San

Angelo soon had the KCM&O shipping large quantities of crude oil.

But production was so substantial that pipelines were laid to the area and

oil shipments by rail dwindled.

Despite the oil bonanza, the

bankruptcy judge forced the KCM&O to be sold in 1924 to pay back

approximately $3 million in debt

owed to the U. S. Government. The high bid was made by Clifford Hister,

Kemper's chief counsel. The financial transactions that ensued were very complex

and subject to a

lengthy court battle that wasn't settled until March, 1927. In the

end, Kemper was the KCM&O's

President. He put the railroad up for sale and was able to secure Santa

Fe's bid buy it. The sale of the KCM&O to Santa Fe was approved by the

Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) on August 28, 1928. |

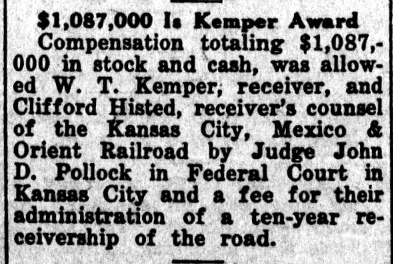

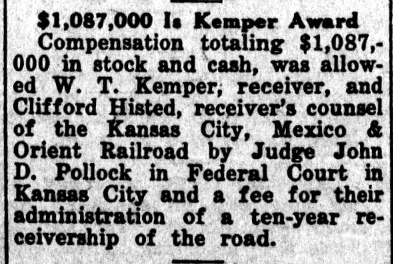

Above: The July 14,

1927 issue of the Paducah Post

reported that the Federal Judge overseeing the KCM&O's bankruptcy had

awarded Kemper and Hister nearly $1.1 million as a fee for managing the

receivership of the KCM&O for ten years. The award amount was

appealed, and the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals reduced it to $800,000

in June, 1928. |

Santa Fe bought the KCM&O along with its Mexican counterpart, the KCM&O of Mexico.

The KCM&O's operations

were quickly integrated with other Santa Fe components but the Mexican line was

sold; it still did not reach

Topolobampo and wouldn't until 1961. A line to the border at Presidio

was built that departed SP's Sunset Route

at Paisano Pass (west of Alpine, reached via trackage rights on SP.) The first

train arrived at Presidio on November 2, 1930. A bridge over the Rio Grande had

been constructed, so the train proceeded on a goodwill tour to Chihuahua,

Mexico. The entire event and tour was filmed by Fox Movietone (with sound!) Santa Fe also built the branch line from San Angelo to

Sonora that KCM&O had planned. The first train reached

Sonora in May, 1930.

Santa Fe bought the KCM&O along with its Mexican counterpart, the KCM&O of Mexico.

The KCM&O's operations

were quickly integrated with other Santa Fe components but the Mexican line was

sold; it still did not reach

Topolobampo and wouldn't until 1961. A line to the border at Presidio

was built that departed SP's Sunset Route

at Paisano Pass (west of Alpine, reached via trackage rights on SP.) The first

train arrived at Presidio on November 2, 1930. A bridge over the Rio Grande had

been constructed, so the train proceeded on a goodwill tour to Chihuahua,

Mexico. The entire event and tour was filmed by Fox Movietone (with sound!) Santa Fe also built the branch line from San Angelo to

Sonora that KCM&O had planned. The first train reached

Sonora in May, 1930.

Except for brief periods, the

KCM&O was never a paying railroad. The physical

dismantling of its route began

in 1977 when the branch to Sonora was scrapped. In 1982, 53 miles was abandoned

between the north side of San Angelo and the community of Maryneal, fifteen

miles south of Sweetwater. The KCM&O tracks from Maryneal to Cherokee,

Oklahoma were sold to the Texas & Oklahoma (T&O) Railroad in 1991. The T&O

abandoned the segment from Sweetwater

to Elmer, Oklahoma in 1995, but the tracks south of Sweetwater were retained,

and they

remain intact today to serve a large cement plant at Maryneal.

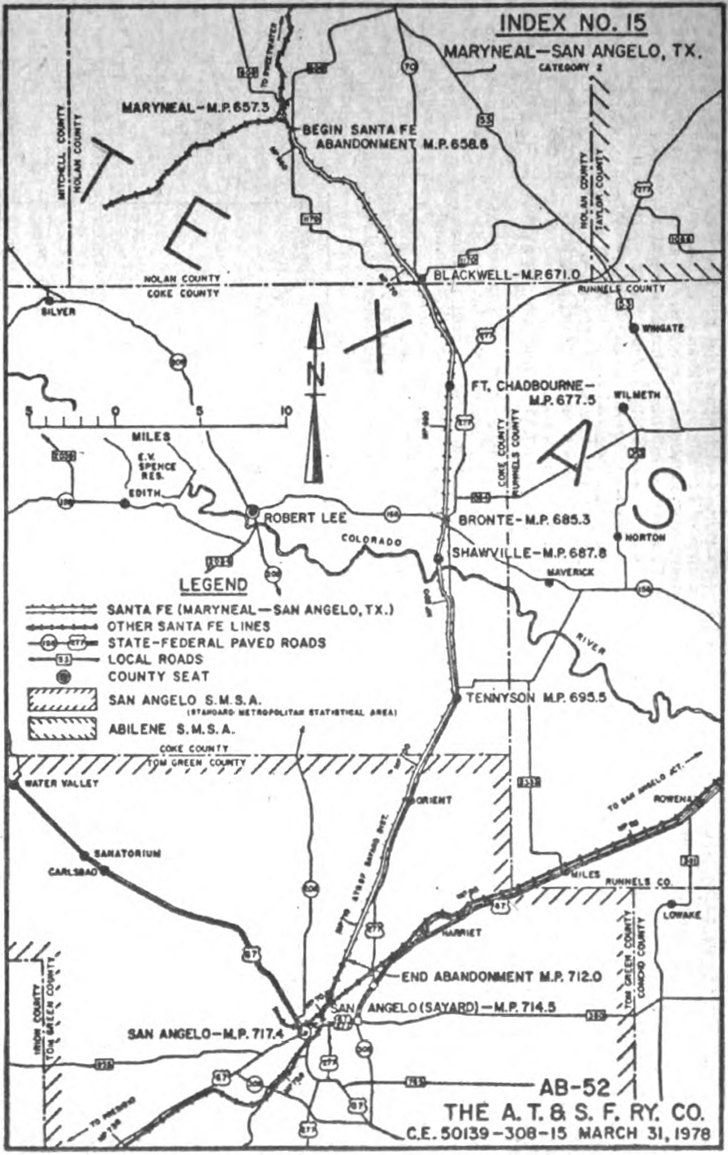

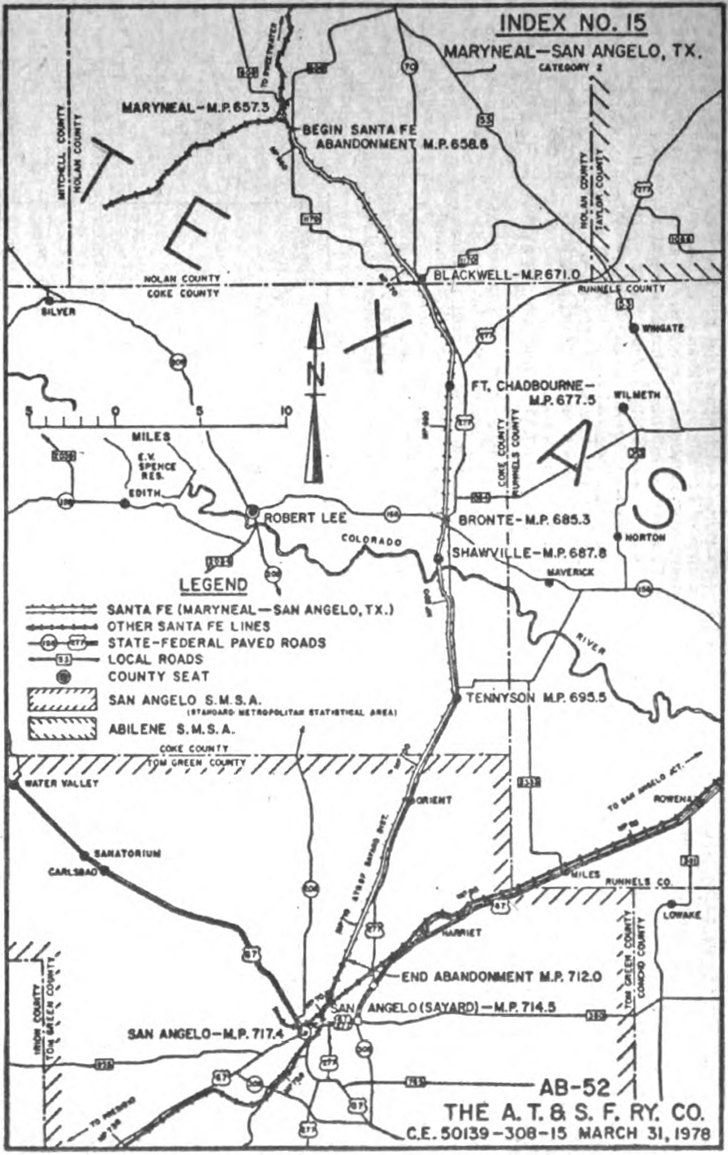

Right: On September 19, 1978, approximately

four years prior to the abandonment between Maryneal and San

Angelo, this map (dated March 31, 1978) was published in the

Federal Register to provide legal notice

that Santa Fe was studying "Maryneal to San Angelo, a 53.4 mile segment of the

Sayard District" for potential abandonment proceedings. Santa Fe timetables show

that at least since 1949 and probably earlier, Santa Fe had proclaimed the former

KCM&O from Hamlin to San Angelo to be the Sayard District of the Slaton Division

of the Panhandle & Santa Fe Railway, a subsidiary that

operated lines in the Texas Panhandle and other parts of northwest Texas. Sayard

was a yard a short distance north of the Tower 82 crossing, but there was no community

by that name. To have named a district for it, Sayard must have been a major yard for Santa Fe. [Was "Sayard" a concatenation of "S. A. Yard", i.e. "San Angelo

Yard", possibly renamed to avoid confusion with the small yard located near the

Santa Fe freight station closer to downtown San Angelo? Enquiring minds want to

know...]

Below: A yard remains in

operation at what is presumably the former location of Sayard a short distance north

of the Tower 82 crossing. (Google Earth 2021)

In

the early 1990s, Santa Fe attempted to sell its entire remaining route through San Angelo

to a company willing to buy it for the scrap value of the rails and other

components. Fearing the loss of a unique transportation corridor in an

underserved section of the state, the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT)

stepped in to acquire the right-of-way. The Legislature established the South

Orient Rural Rail Transportation District to acquire the track and other items

directly from Santa Fe. A new company, the South Orient Railroad, was founded to

acquire the operating rights and obligations for the line from Santa Fe. South

Orient operated the tracks from San Angelo Junction on the

Santa Fe main line to Presidio on the Rio Grande, a total of 376 miles. The

segment from San Angelo to Presidio was KCM&O heritage; the segment between San

Angelo and San Angelo Junction was GC&SF heritage.

In June, 1998, South

Orient applied to the Surface Transportation Board (STB) for permission to

abandon the line from San Angelo to Presidio. Instead, the Legislature funded TxDOT to acquire all of South Orient's interests and arrange to lease operation

of the entire rail line. A new company based in San Angelo,

Texas Pacifico Railroad, took the

lease. STB approved this arrangement on December 11, 2000, and

Texas Pacifico continues to operate the line today.

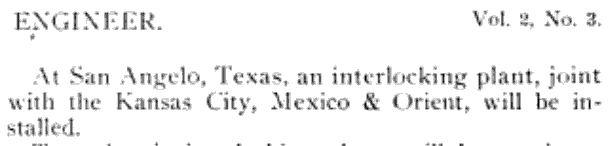

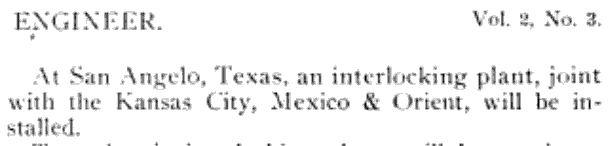

Above: In June, 1909,

The Signal Engineer had this item

in an article about Santa Fe's interlocking plans

for the year. |

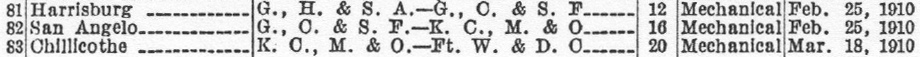

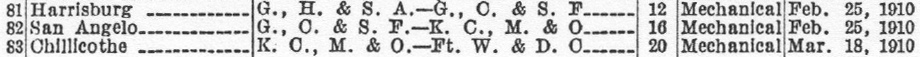

Above: The RCT interlocker list of October 31, 1910

shows that Tower 82

began operation on February 25, 1910.

Below: RCT's list of inactive interlockers dated December 31, 1930

included Tower 82, but reported its original commissioning date as December 28, 1910

instead of February 25, 1910. This was Tower 82's first appearance in

the list of inactive interlockers.

|

In the book The Orient, the authors assert that

Tower 82's construction began on September 1, 1910 and was completed on February

25, 1911. If so, RCT's originally published commissioning date was off by

exactly one year. The truth may lay somewhere in between, perhaps the revised

date of December 28, 1910. In RCT's interlocker list published at the end of

1916, Tower 82's commissioning date was left blank. Each annual list of active

interlockers continued with the blank commissioning date until the list dated

December 31, 1923 reinserted the original date. Even RCT was confused.

Tower 82 initially had sixteen functions; the minimum count for a basic crossing was twelve, consisting

of a home signal, distant signal and derail in each of the four directions. The

purpose of its four additional functions is undetermined,

but could indicate the presence of a connecting track (aerial imagery shows a

northeast quadrant connecting track present in 1954.) In RCT's published table of

active interlockers dated October 31, 1916, the function count increased to eighteen.

This was also the first RCT table that identified the railroad responsible for

operating and maintaining the interlocker; for Tower 82, it was the GC&SF. This

suggests that the GC&SF took the lead on designing the tower and interlocking system

because typically, the railroad that built the interlocker also handled

operations

and maintenance (O&M) staffing, at least at the outset. Under state law, KCM&O -- the railroad

that created the crossing when it built across the GC&SF -- would have been

responsible for funding the capital expense for the tower, interlocker and associated signals. (Had the crossing existed before 1901,

the capital expense would have been shared.) In most cases, the

railroad that funded the tower would also take the lead in building it, but it

is likely that by the time the tower was being planned for San Angelo, Santa Fe

already knew it would soon be building across the KCM&O at Sweetwater. There,

they would be the second railroad and thus would be obligated to fund the capital

expense for the tower in Sweetwater, eventually nomenclatured by RCT as Tower 88. Since

the KCM&O had

no experience in designing and building interlocking towers, and given that Santa

Fe would need to fund the capital outlay for the Sweetwater tower within a year

or so, it is likely that the two towers were identical designs (but

unfortunately, this is merely conjecture as no photo of the Sweetwater tower has

surfaced.)

The photo

of Tower 82 at the top of page shows a structure that resembles other GC&SF towers, but not

precisely (see Tower 23,

Tower 24 and Tower 52 for examples.) Like the

others, Tower 82 is constructed with narrow, horizontally mounted wood boards

and four upper floor windows, at least on the visible side. The far wall windows

that are visible through the near windows appear to be the correct distance for

a square floor plan, another common element of GC&SF towers. The roof overhang,

however, appears to be smaller, and there is no obvious accent paint scheme

(perhaps merely a function of when the photo was taken.)

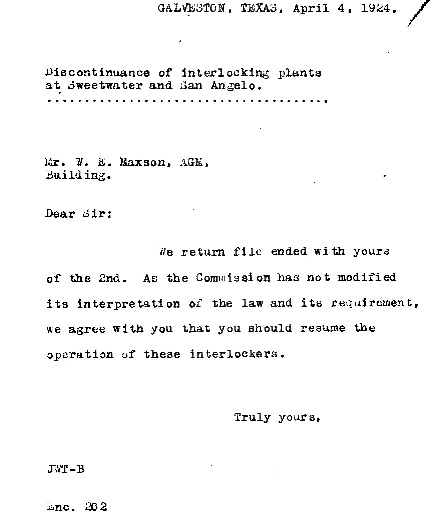

Left:

This letter was sent to W. E. Maxson, Assistant General

Manager ("AGM") of the GC&SF, in 1924. The best guess is that it was written by an attorney

at the GC&SF corporate office ("Galveston"), someone Maxson

recognized simply by the initials, and it was sent to Maxson's office in

the same location (addressed simply as "Building.") It suggests that Maxson had

requested a legal opinion regarding interlockers at Sweetwater

and San Angelo that had been taken out of service by Santa Fe at some unknown date. The author agreed with Maxson's position that Santa Fe

should resume operation of both interlockers. The "interpretation of the law" referenced in

the letter relates to legal issues that had been raised

regarding the extent of RCT's authority over interlockers. For example, since

Texas' interlocker law specifically referred to a crossing of "another company",

could RCT order an interlocker

installation for a junction where all of the tracks belonged to the same company?

Could RCT require a railroad to seek approval of an interlocker that the

railroad had voluntarily installed for its own purposes? Under what

circumstances (if any) did a railroad have an inherent right to stop operating

an interlocker (e.g. bankruptcy, merger?) Some of these issues had already surfaced with respect to

other interlockers (see

Tower 5, Tower 116 and Tower 121),

and the issue would come back to haunt Santa Fe when they voluntarily chose to install an interlocker at Canyon

in 1927. (Santa Fe Legal Archives, Houston Metropolitan Research Center. Thanks to Stephen Hesse

for finding this document.)

Left:

This letter was sent to W. E. Maxson, Assistant General

Manager ("AGM") of the GC&SF, in 1924. The best guess is that it was written by an attorney

at the GC&SF corporate office ("Galveston"), someone Maxson

recognized simply by the initials, and it was sent to Maxson's office in

the same location (addressed simply as "Building.") It suggests that Maxson had

requested a legal opinion regarding interlockers at Sweetwater

and San Angelo that had been taken out of service by Santa Fe at some unknown date. The author agreed with Maxson's position that Santa Fe

should resume operation of both interlockers. The "interpretation of the law" referenced in

the letter relates to legal issues that had been raised

regarding the extent of RCT's authority over interlockers. For example, since

Texas' interlocker law specifically referred to a crossing of "another company",

could RCT order an interlocker

installation for a junction where all of the tracks belonged to the same company?

Could RCT require a railroad to seek approval of an interlocker that the

railroad had voluntarily installed for its own purposes? Under what

circumstances (if any) did a railroad have an inherent right to stop operating

an interlocker (e.g. bankruptcy, merger?) Some of these issues had already surfaced with respect to

other interlockers (see

Tower 5, Tower 116 and Tower 121),

and the issue would come back to haunt Santa Fe when they voluntarily chose to install an interlocker at Canyon

in 1927. (Santa Fe Legal Archives, Houston Metropolitan Research Center. Thanks to Stephen Hesse

for finding this document.)

This letter is difficult to interpret

within the context of what is known about the interlockers at San Angelo and

Sweetwater. Both were operated by Santa Fe and both involved the KCM&O as the

other railroad (KCM&O also had an interlocker at

Chillicothe that did not involve Santa Fe.) At an unknown date the GC&SF

discontinued operating these interlockers, but Maxson had concluded that restarting

them might be required under RCT rules. Since KCM&O was paying half of the

interlockers' O&M expenses, had the railroads agreed to suspend operations so

KCM&O could save money when it reentered receivership in 1917? Was it

required by the bankruptcy Receiver? Did Santa

Fe do it on their own because KCM&O had stopped paying their share of tower

expenses, or because KCM&O's train count had dropped so low that a manned

interlocker made no sense? Had KCM&O complained to Santa Fe or to RCT about the

suspended interlockers? By 1924, KCM&O was shipping large quantities of Big Lake

crude eastward. Such trains would have been long and heavy, with no need to stop

in San Angelo, precisely the type of train that would be penalized the most by

being forced to stop before crossing the Santa Fe diamond if Tower 82 was inactive. Did

the San Angelo and Sweetwater interlockers have any other common factors that made

them candidates to be closed? Does the removal of the Tower 82 commissioning

date in RCT's annual lists from 1916 through 1922 pertain to this subject at

all? These are questions that require additional research through Santa Fe's

archives.

Tower 82 first appeared in RCT's annual list of

inactive interlockers at the end of 1930. This was the final

comprehensive list of active and inactive interlockers that RCT ever published.

Since Santa Fe owned both rail lines, it made sense to seek RCT permission to decommission Tower 82

(which RCT apparently granted, given Tower 82's inclusion in the list of retired

interlockers.) Based

on the suspension referenced in the letter to Maxson, Santa Fe had presumably

for several years held the belief that Tower 82 was not cost-effective for their

operations through San Angelo. Apparently there would be few trains materially

impacted by the need to come to a complete stop before crossing the diamond,

whereas the cost of staffing and maintaining the interlocking tower would be

significant. Given Tower 82's relatively early demise and its location on the

north outskirts of San Angelo (far from town back in the 1920s), it is perhaps

not surprising that no reports

have surfaced regarding the dismantling and disposition of the tower.

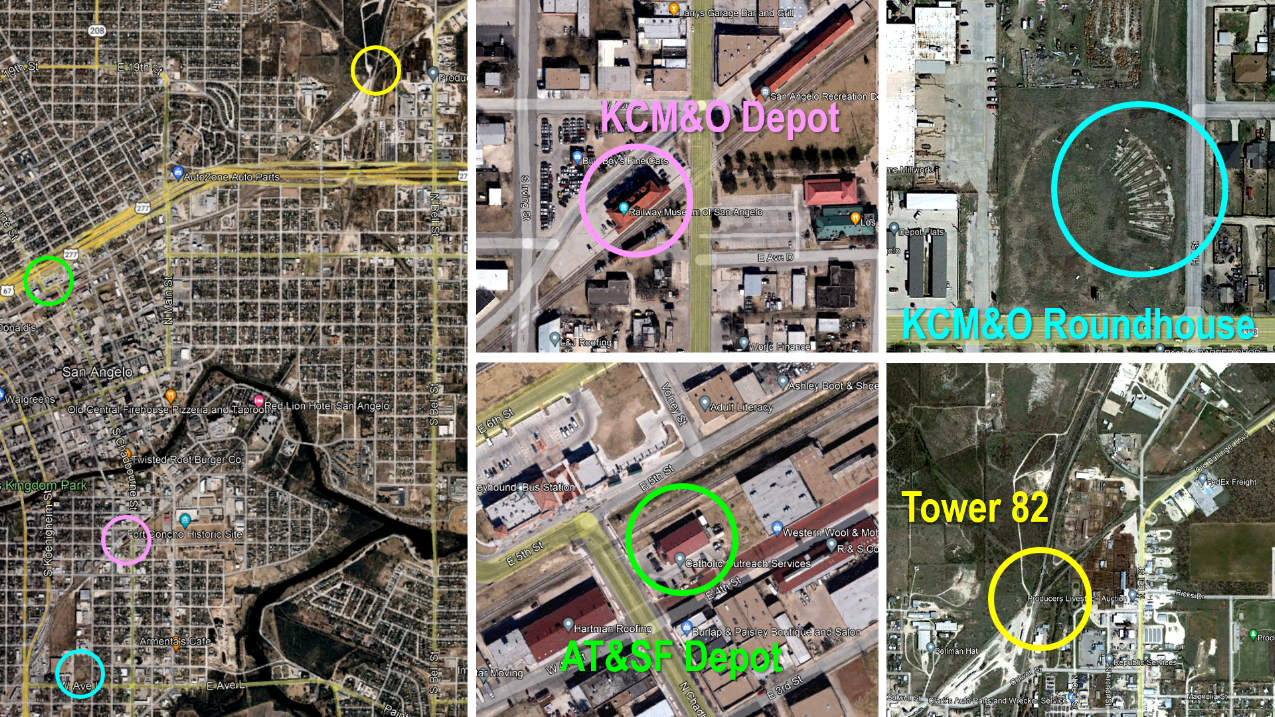

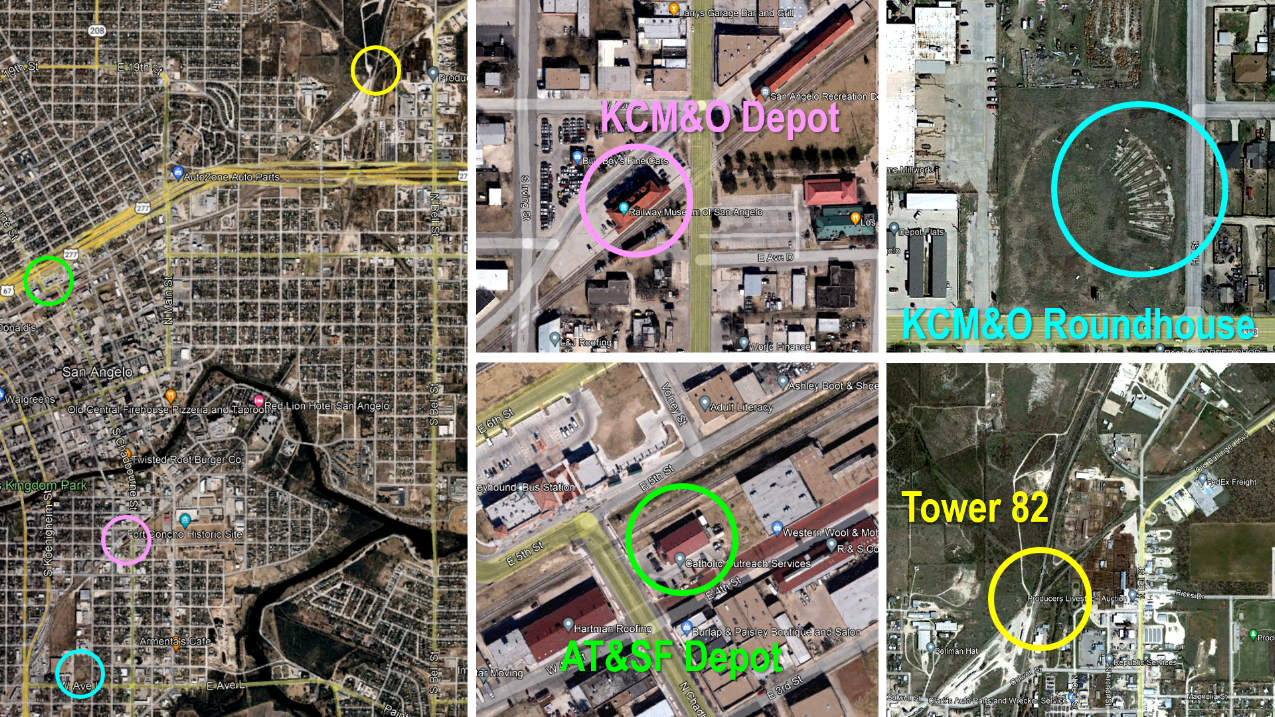

Above: These March, 2021

Google Earth images are annotated with key locations in San Angelo railroad

history:

Although the name "Alvery Junction" has come to be

associated with the area near the Tower 82 crossing, Santa Fe timetables always referred to Tower 82 as

"Alvey Junction." The source of this discrepancy has not been determined. South of the

junction, the GC&SF tracks

were severed when the US 277 expressway opened in the mid-1990s. A connection

between the KCM&O tracks and the GC&SF tracks was built parallel to and

south of the freeway to retain access to industries located along the GC&SF

tracks in north San Angelo. North of Alvey Junction, the connecting

track visible in the image has existed since at least 1954. Does this interchange track date back to when Tower 82

was erected? RCT reported the

interlocker having four functions beyond the minimum, e.g. perhaps a switch and

a signal at each end of the connector? Farther north (but not on these images), the former Sayard

facility

is still in use, and a new San Angelo Rail

Park is under construction as of June, 2022.

Timetables show that at least

by 1945 (and probably many years earlier), Santa Fe had

relocated its passenger operations to the KCM&O depot. This required

passenger trains on the San Angelo District

(east to San Angelo Junction or west to Sterling City) to detour 2.2

miles on the Sayard District south from Alvey Junction to reach the depot.

The Santa Fe

depot (dating to 1908 or earlier) remains standing as a facility for Catholic Outreach Services.

West of the depot, the tracks end just beyond W. 19th St. on the former route to

Sterling City. Remnants of the KCM&O roundhouse

are visible in a large field at the

intersection of Hill St. and W. Ave. L.

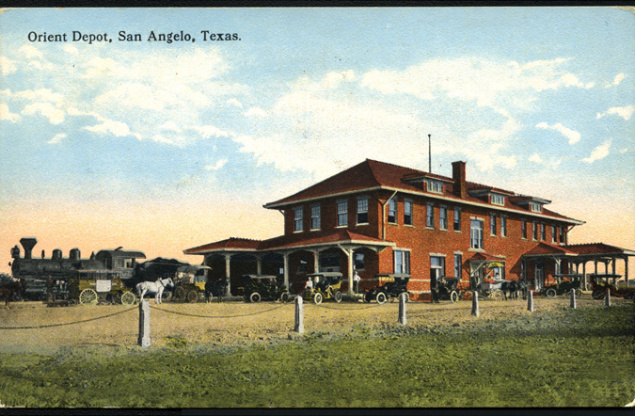

Above:

the Santa Fe passenger depot in San Angelo:

left,

Margay Welch collection, 1908; right, a Catholic Outreach Services facility -- Google Street View,

2012

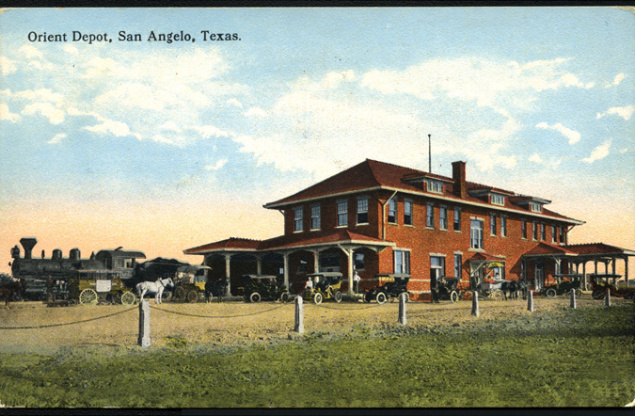

Above Left: the KCM&O depot,

(c) M. C. Ragsdale c.1910 (courtesy of the Texas Transportation Archive, Murry

Hammond collection) Above Right: The

Railway Museum of San Angelo

was established in 1996 housed in the former KCM&O depot. At some point, Santa

Fe moved all of their passenger operations to this depot. The last regularly scheduled passenger train departed the depot on June 20,

1965. Santa Fe deeded the facility to the city of San Angelo in 1989 and it was

restored over several years. (William Fischer, 2014)

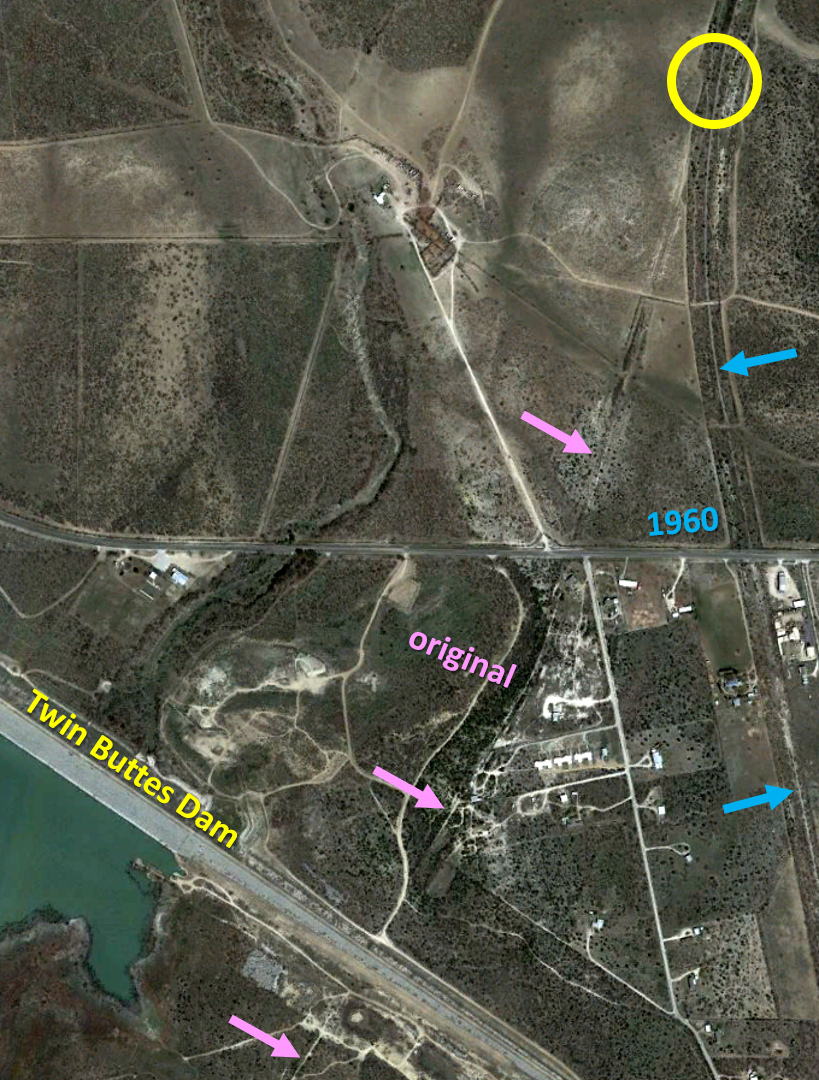

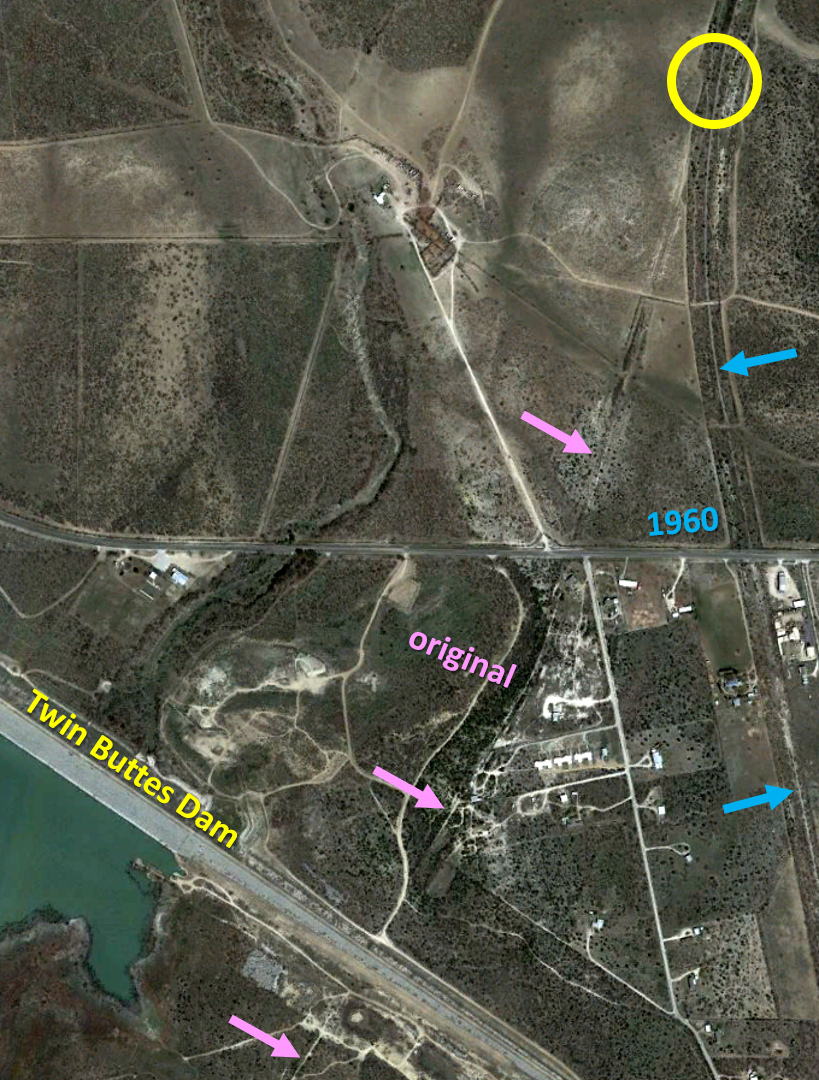

Above: In 1960, construction

of the Twin Buttes Dam began for the purpose of impounding Twin Buttes

Reservoir southwest of downtown San Angelo. Santa Fe's tracks to Fort Stockton

passed through the middle of it, so they were realigned to go around the north

side. The red solid lines are the unaffected parts of the right-of-way leading

to the east junction (orange circle) and west junction (green circle.)

Left:

The Twin Buttes Dam is an unusual design that

separately dams both the Middle and South Concho Rivers with a rolled earthfill

embankment nearly eight miles long. In addition to requiring a relocation of

Santa Fe's tracks to Fort Stockton, the south end of the dam also crossed Santa Fe's tracks to Sonora, requiring a relatively short realignment. The new

right-of-way (blue arrows) began at the yellow circle (at coordinates 31 19 38

N, 100 28 27 W) and rejoined the original right-of-way (pink arrows) about three

miles farther south (at 31 15 59 N, 100 29 40 W).

Left:

The Twin Buttes Dam is an unusual design that

separately dams both the Middle and South Concho Rivers with a rolled earthfill

embankment nearly eight miles long. In addition to requiring a relocation of

Santa Fe's tracks to Fort Stockton, the south end of the dam also crossed Santa Fe's tracks to Sonora, requiring a relatively short realignment. The new

right-of-way (blue arrows) began at the yellow circle (at coordinates 31 19 38

N, 100 28 27 W) and rejoined the original right-of-way (pink arrows) about three

miles farther south (at 31 15 59 N, 100 29 40 W).

In hearings held in

1957 before the U. S. House of Representatives Interior and Insular Affairs Committee,

witness Robert W. Jennings of the Bureau of Reclamation stated... "Twin Buttes

Dam would span both the Middle and South Concho Rivers just upstream from Lake Nasworthy and the municipal airport, Mathis Field."

Nevertheless, the dam was more frequently called the "Three Rivers Dam" by San

Angelo civic leaders, particularly Houston Harte, the Publisher of the

San Angelo Standard (and co-founder of the

major communications company,

Harte Hanks.)

The outflow from Twin Buttes Reservoir flows into Lake Nasworthy, a small lake

built in 1930 as a municipal water supply for San Angelo.

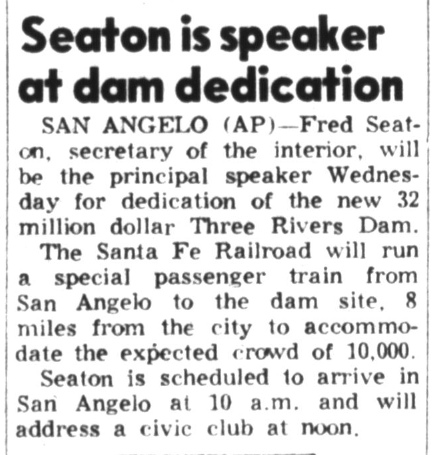

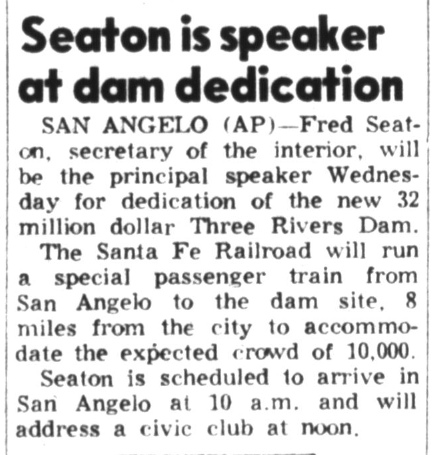

Below: The

Levelland Daily Sun News of June 21, 1960

noted that Santa Fe was running a special train to "Three Rivers Dam" for

its dedication at which Secretary of the Interior Fred Seaton would

be the principal speaker. The Twin Buttes name eventually won out, perhaps to

avoid conflict with a dam built near Three Rivers, Texas for Choke Canyon

Reservoir.

Santa Fe bought the KCM&O along with its Mexican counterpart, the KCM&O of Mexico.

The KCM&O's operations

were quickly integrated with other Santa Fe components but the Mexican line was

sold; i

Santa Fe bought the KCM&O along with its Mexican counterpart, the KCM&O of Mexico.

The KCM&O's operations

were quickly integrated with other Santa Fe components but the Mexican line was

sold; i