Texas Railroad History - Tower 100 - Elgin

A Crossing of the Houston & Texas Central Railway and the Missouri, Kansas

& Texas Railway

Above: Southern

Pacific #894 obscures the Elgin Union Depot in the background as it passes Tower 100 eastbound in this undated photo. (Bruce Wilson

collection) Below: John W.

Barriger III took this photo of Tower 100 from the rear platform of his business car

sometime in the 1930s or perhaps the early 1940s. His camera is facing north

as his train proceeds south on the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railway main line

toward

Smithville. The tower sat in the southeast quadrant of the crossing, diagonally across

from Elgin Union Depot. (John W Barriger III National Railroad Library)

The Galveston & Red River (G&RR) Railway was chartered

in 1848 with a grand plan to connect the port of Galveston with the Red River. Railroads from the Midwest were

anticipated to bridge the river and enter Texas from Indian Territory

(Oklahoma) creating an important export route for grain and other

commodities. Unable to raise

sufficient capital, the project languished until an unrelated opportunity arose:

farming interests in Chappell Hill needed better transportation to the

Houston market. Chappell Hill was only sixty miles

northwest of Houston but it was west of the flood-prone Brazos River, a wide and formidable obstacle.

A meeting was held in 1852 to discuss Chappell Hill's transportation issues;

Paul Bremond, one of the founders of the G&RR, attended. He suggested that in

exchange for financial backing from Chappell Hill investors, the G&RR could be

re-chartered to start construction in Houston and pass near Chappell Hill,

remaining east of the Brazos. A branch line would be needed since crossing

the Brazos was unnecessary for the G&RR to reach the Red River. Bremond's proposal was accepted and the

Legislature approved the change in 1853.

In 1856, the G&RR completed its first 25 miles

out of Houston to Cypress, arriving there just as the Legislature approved another

charter amendment granting the railroad a new name,

the Houston & Texas Central (H&TC) Railway. Much to the chagrin of

Chappell Hill's resident investors, the amendment prohibited H&TC from building branch lines until the

tracks to the Red River were completed. But the outlook was not completely bleak

for Chappell Hill because a plan was being developed by businessmen in the

nearby town of

Brenham to build a railroad to connect to the H&TC.

The Washington County Rail Road (WCRR) would pass through Chappell Hill as it

headed toward a bridge to be built over the Brazos River. The WCRR charter was granted

by the Legislature in February, 1856. By the end of

that year, the Hempstead Town Co. was being organized to sell lots at a town

site chosen to be the

connecting point for the WCRR.

|

In 1858, the H&TC reached Hempstead from Cypress and continued

construction north toward Navasota. The

WCRR began construction westward from Hempstead in June, 1858 --

starting there allowed construction materials to be shipped from

Galveston by rail on the H&TC. Seven miles of track reaching the east bank of the Brazos

River was in place by early 1859. Bridging the Brazos took two

years; the first train from Hempstead to Chappell Hill ran in

early 1861. The WCRR line was finished soon thereafter with service into Brenham in April, 1861.

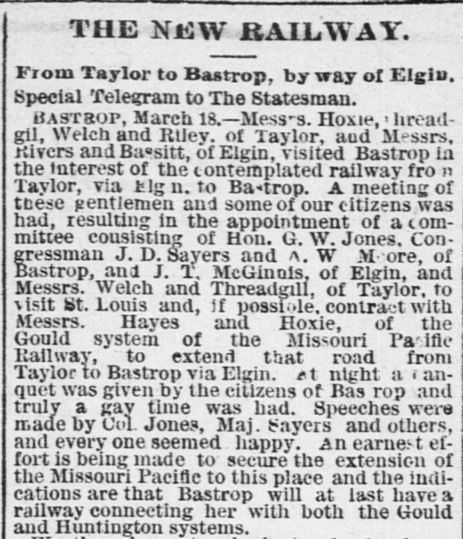

Left: Houston

Weekly Telegraph, February 5, 1861

As the Civil

War heated up, the H&TC terminated northward construction at Millican,

ten rail

miles north of Navasota. |

The WCRR continued operating during the War. Author S. G. Reed, in his classic reference

A History of the Texas Railroads (St. Clair

Publishing, 1941), explained that ultimately ...

"... it could not meet its

obligations and on June 2, 1868, was sold under foreclosure. The Sheriff

happened to be W. M. Sledge, the man who had built the road as a contractor, and

who owned three-fifths of the stock. He was the purchaser. The roadbed needed

repairs and the equipment was almost worn out, and the Washington County people

wanted it extended to the Capital at Austin. Sledge was not able to do so

himself, so on March 11, 1869, he sold it to the H. & T. C."

This was not Sledge's first rodeo ... railroad.

In 1867, he had been awarded the Buffalo Bayou, Brazos & Colorado (BBB&C)

Railway in

a court judgment for non-payment of his construction

contract (see Tower 17.) Sledge tried to operate the BBB&C before

selling it to Thomas Peirce in 1870. Peirce renamed it the Galveston,

Harrisburg & San Antonio (GH&SA) Railway and extended it to

San Antonio and

El Paso. Southern Pacific (SP) provided funding for the El Paso extension

and in 1883, leased and then acquired the GH&SA.

The WCRR had been supplying steady traffic at Hempstead, enough that the H&TC

had been willing to loan the WCRR $80,000 for repair work. Sledge extinguished this debt

by selling the WCRR. Although

the H&TC charter prevented the railroad from building branch lines until the main line to the Red River was

complete, the charter did not prevent the H&TC from investing in branch lines

being built under other railroad charters. The H&TC's

founders had long been projecting two major branch lines to the west, one of

which would go through

Austin continuing northwest to the Texas Panhandle. The purchase of the WCRR allowed the H&TC to get a head

start on this branch (which ultimately stopped at Llano and went no further.) The

construction to Austin began in 1870 when the H&TC built 42 miles from Brenham to

Hills (a community six miles west of Giddings.) The remaining 51

miles to Austin was built in 1871. The first train into

Austin arrived on Christmas Day, about a year before the H&TC's northward

construction reached Denison at the Red River.

The WCRR and the extension to Austin were

built at

state gauge,

5 ft. 6 in., as required by state law (narrow gauge, 3 ft., was

also permitted.) Many states (and the

Transcontinental Railroad) used standard gauge, 4 ft. 8.5 in.,

thus interstate traffic exchange was problematic for Texas railroads. In the early

1870s, state gauge fell into disfavor, and exceptions were already being permitted, e.g. the H&TC main line north of

Corsicana was built c.1871 at standard

gauge. By 1874, most Texas railroads were looking to switch to standard

gauge, and the law was changed in 1875.

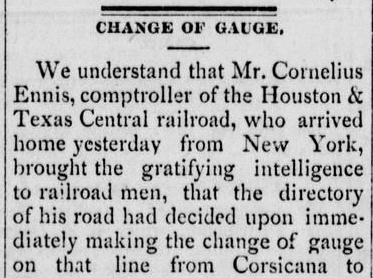

Right: The

Denison Daily News of September 9, 1874 quotes the Houston Telegraph

celebrating the news that the H&TC was changing the Corsicana -

Hearne tracks to standard gauge. The

Telegraph

also noted that the Hearne - Hempstead tracks needed to be changed. A "third rail"

from Hempstead to Houston would then allow operations at both gauges, i.e. for Austin trains

at state gauge and for trains north of Hempstead at standard gauge. H&TC's

branch to Austin was converted to standard gauge in 1877. |

|

|

As the H&TC had built toward Austin in 1871, a new

settlement, Glasscock, became a flag stop in Bastrop County. When the town was platted in 1872,

the name was changed to Elgin in honor of Robert Elgin, the land commissioner

and surveyor for the H&TC. Elgin was fifteen miles

north of the county seat, Bastrop, which did not have rail service despite years

of trying to interest investors in building a line to Austin. Elgin, like

most small towns in east central Texas, had an economy based

on farming. In 1884, a brick manufacturing facility opened and Elgin soon

became widely known as a brick-making center, an industry ideally served by rail

transportation. Elgin's economy was further stimulated

when a second railroad began construction at Elgin in June, 1886.

|

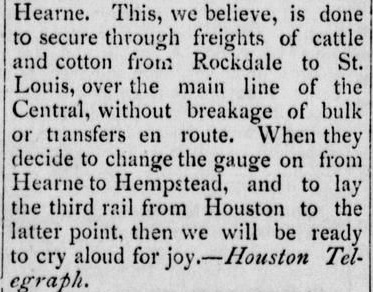

Left:

The Austin Weekly Statesman of

March 19, 1885 carried this story discussing a VIP meeting about a

potential railroad to run from Taylor to Bastrop, a 35-mile straight line with Elgin at the midpoint. The reporter

correctly surmised that the presence of Herbert M. "Hub" Hoxie, General

Superintendent of the International & Great Northern (I&GN) Railroad,

meant that rail baron Jay Gould was backing the plan. The "Huntington"

reference was to SP President C. P. Huntington. SP had acquired the H&TC

in 1883, making the line through Elgin part of SP's route network.

The Missouri, Kansas & Texas (MK&T, "Katy") Railroad

built a bridge over the Red

River and entered Denison in 1872. For several years it built no further, handing its traffic to the H&TC

for delivery to points south. In 1879, Jay Gould was elected President

of the Katy, an outcome attributable to loyalists sent by Gould to

infiltrate Katy management over a period of several years. Gould began a southward expansion

in 1880 by leasing the Katy to Missouri Pacific (MP), a major Midwest

railroad in which he had significant ownership. The lease had

onerous terms, siphoning Katy profits into MP for Gould's financial gain

while Katy stockholders fared poorly. MP did not have a Texas railroad

charter nor was it headquartered in state (as required by Texas law for

track ownership.) Thus, for legal reasons, Gould's

southward construction was credited officially to the Katy, but Gould

ensured that the press conveyed it to the public as an MP activity.

Going south from Denison via Fort Worth and

Waco, the MP / Katy line reached Taylor in

1882 and connected with tracks of the I&GN that ran from Longview to

Laredo via Austin and San Antonio. In 1881,

Gould had acquired the I&GN using Katy stock in a swap for I&GN stock.

Since the I&GN was well-known as

Texas' largest railroad, it was allowed to continue to operate under its

own name, even as Gould leased it to the Katy.

The plan was to

build to Houston, but Gould paused

the

MP / Katy construction at Taylor due to the political climate in the Texas Legislature.

In 1882, it had repealed the land grant law and lowered authorized

passenger fares while pondering additional railroad regulation. By 1885,

Gould had decided to resume construction out of Taylor. He would cross the H&TC tracks at

Elgin and continue farther south to Bastrop before turning southeast

toward Houston. The route would be comfortably south of SP's H&TC

(Austin - Houston) line but well north of SP's GH&SA (San Antonio - Houston) line. The new

railroad materialized as the Bastrop & Taylor (B&T) Railway, chartered in April,

1886. The charter was amended on October 27, 1886 to increase its

capitalization and change the name to the Taylor, Bastrop & Houston

(TB&H) Railway. Gould had sent his close associate Hub Hoxie to make

it all happen, but Hoxie's tenure as a TB&H Director was

brief; he died in New York less than a month later on November 23, 1886. |

The press in Austin was apoplectic about the prospect

of a Taylor - Houston route via Bastrop. Like Austin, Bastrop was on the

Colorado River, 28 miles southeast. It had no railroad but it was a

county seat with 2,000 residents and was a major cotton producing area. The anxiety

among Austin businessmen came from the realization that Gould's railroad would capture Bastrop commerce

for Elgin, Taylor and Houston, whereas Bastrop had long been dependent on Austin for many

commercial activities. As plans for a railroad into Bastrop solidified, the Bastrop Advertiser

roundly criticized the Austin Statesman

for suddenly promoting the idea of a Taylor - Bastrop - Austin alternative

routing after years of failing to advocate for an Austin

- Bastrop railroad. The Advertiser described the

Statesman as "...suddenly waking up from a long

Rip Van Winkle sleep ... and discern[ing] ... the thousands of bales of Bastrop

cotton and hundreds of thousands of dollars of Bastrop patronage which will be

annually lost to Austin..."

Austin business leaders also feared

that the new line would reduce freight traffic through Austin. As long as the MP

/ Katy tracks terminated at Taylor, trains coming south through Waco and

Temple could only proceed

farther south via the I&GN through Austin. But Bastrop and Smithville were both

within fifty miles of San Marcos which was on the I&GN between Austin and San

Antonio. A branch to connect San Marcos with Bastrop or Smithville would be an

obvious move for Gould. Indeed, Smithville was ultimately selected for the

branch line based on where Gould chose to cross the Colorado River. Gould

freight between the Red River and San Antonio could opt to bypass the

tracks through downtown Austin by using a Taylor - Smithville - San Marcos - San

Antonio routing. As an added plus, a branch line between Smithville and San

Marcos would pass through Lockhart, the county seat of Caldwell County, another source of passengers and commerce.

|

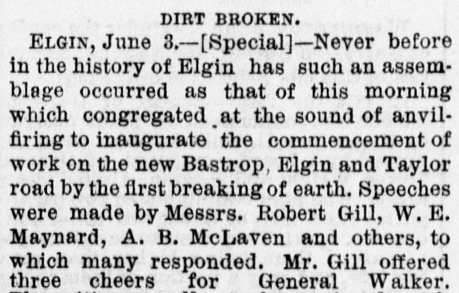

Left: The

Galveston Daily News of June 4, 1886 reported on a ceremony

at Elgin signifying the start of construction on the B&T. Elgin was

chosen because rail and other materials arriving at the Port of

Galveston could be shipped to Elgin on the H&TC. The article calls the railroad the "Bastrop,

Elgin and Taylor", perhaps an aspirational name but never an official

one. The TB&H name was formally adopted four months later when the

charter was amended.

Right:

The Fort Worth Daily Gazette

of June 17, 1887 reported completion of the Colorado River bridge at

Bastrop. As noted, Smithville got the branch line to Lockhart continuing to

San Marcos, but the San Antonio & Aransas Pass (SA&AP) was not involved.

By the end of 1887, the TB&H had been acquired by the Katy.

As rumored, the MP / Katy shops were built in Smithville. |

|

The TB&H construction had continued beyond

Bastrop during the remainder of 1887, reaching Smithville and La Grange. Gould

also initiated construction on the branch line between San Marcos

and Smithville. Track-laying started at San Marcos and went east to Lockhart, but

it stopped there, 36 miles shy of Smithville, as dark financial clouds

began to impair Gould's activities. One of his railroads, the Wabash, St. Louis

& Pacific Railway, had entered receivership. It was indirectly leased to MP

thereby

affecting MP's operations and cash flow. On top of his problems outside of

Texas, Gould was under attack by new Texas Attorney General James S. (Jim) Hogg.

Hogg had been elected in November, 1886 on a campaign to go after railroads for

poor service, poor facilities and price-fixing.

As all of this was

happening, Gould was trying to prevent Katy stockholders from summoning a

quorum for a stockholders' meeting where they would undoubtedly fire him for the

detrimental impact of MP's lease. Gould had very little ownership in the Katy;

its stock was widely diluted and there were few large blocks available for

private purchase. This left Gould vulnerable to Katy stockholders, but only if

they could gather a quorum for an official meeting. Combined with the Wabash

bankruptcy and multiple lawsuits filed by Hogg, the situation in 1887 evolved

to the point where Gould ordered all MP construction to cease immediately. The

San Marcos - Smithville branch stopped at Lockhart, and the TB&H tracks stopped

eleven miles east of La Grange, a location christened Boggy Tank.

A turntable and siding tracks were installed so that passenger trains could serve the small

population in the vicinity.

Katy

stockholders were finally able to hold an official meeting in May, 1888 and they

fired Gould for malfeasance associated with MP's lease. New Katy management

promptly sought bankruptcy protection and a declaration that MP's lease was

void. Eventually, the Texas Supreme Court terminated MP's lease of the Katy

while also declaring the Katy to be a "foreign" railroad because it lacked a

Texas charter and headquarters. An 1870 Texas law had granted the Katy

permission to build into Denison from Indian Territory under the

authority of its Kansas railroad charter. The Supreme Court concluded that

the Katy should not have built further into Texas without a Texas charter and a

Texas headquarters. The Katy would operate under a court-appointed Receiver

until a proper Texas charter could be granted by the Legislature.

Gould

wanted to prevent the Katy from being allowed to retain ownership of the I&GN.

He was, ironically, still President of the I&GN. He had taken a risk using the Katy for his expansion plans; it was no secret

that the Katy lacked a Texas charter and headquarters. Gould's argument was that the Kansas charter

accepted for building into Denison also called for

the Katy to build south to Mexico, a plan he was basically following.

Texas legislators looked the other way; they enjoyed giving speeches to constituents

when towns celebrated the arrival of new MP / Katy tracks. In receivership, Katy

management was in no position to evict Gould from the I&GN, and it would have

had difficulty proving its ownership anyway. Gould had been sufficiently

concerned about the Katy's "foreign railroad" status that he had finessed the

actual ownership of the I&GN. Having acquired all of its stock certificates

in the swap for Katy stock, he placed them with his

close friend, Gen. Grenville Dodge, ostensibly a Texas resident at the time (in

Fort Worth), hence the stock was held at a

Texas headquarters, if you could call it that. Dodge was currently the Chief

Engineer for the Texas & Pacific Railway of which Gould was President, but he

was most famously known as the Chief Engineer for the

Transcontinental Railroad. Since Gould was focused on retaining the I&GN, he

decided to admit

to Hogg that the Katy

really was the I&GN's owner. By law, a foreign railroad could

not own a Texas railroad directly; it had to use an in-state subsidiary which

the Katy had not done. Hogg took the bait and jumped into the legal fray to try

to force the Katy to divest

the I&GN.

Gould engineered additional legal delay by putting the I&GN into bankruptcy over

a minor debt owed to himself that, as I&GN President, he had refused to

repay! Gould was ruthless but brilliant...

|

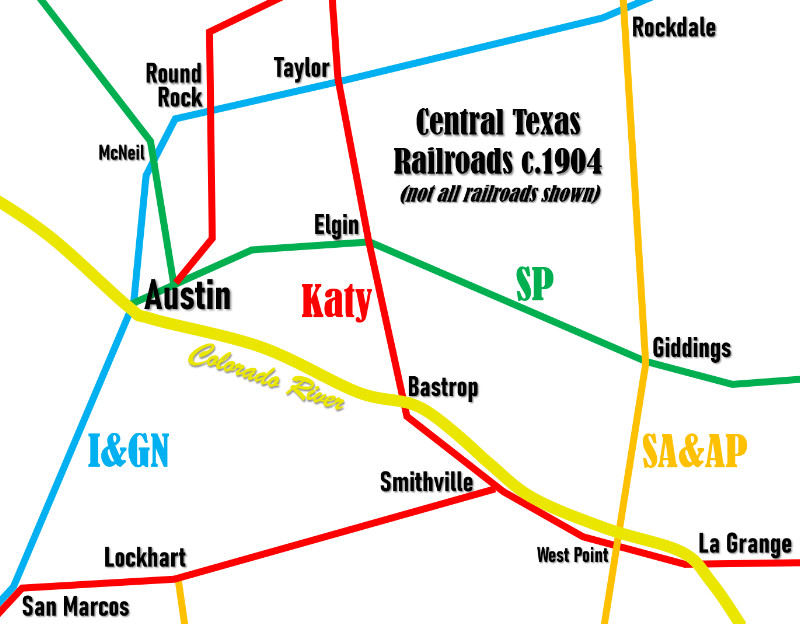

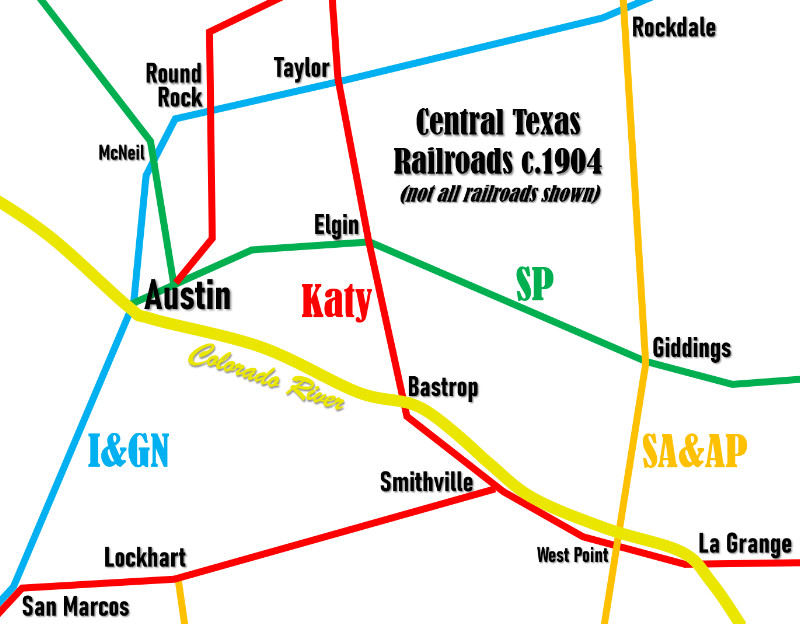

Left: This

overview map shows the railroads in the vicinity of Elgin c.1904.

It is apparent

that Gould's initial TB&H planning included the branch to San Marcos

because he otherwise could have avoided the expense of bridging the

Colorado River twice. Remaining north

of the river straight

from Bastrop to La Grange was a simpler alternative. Both town centers

were east and north of the river, hence no river crossing was needed to

proceed to Houston. The tracks would have passed along the river bank

across from Smithville and would likely have induced residents to shift

the town center to the north side of the river (it's only a quarter mile

south of the river today.) But crossing the Colorado River once --

necessary for a branch to San Marcos -- meant crossing it twice --

because the river turns south at La Grange.

Ultimately, there were numbered

interlocking plants at Elgin, Austin,

San Marcos, West

Point, Taylor,

Rockdale and McNeil. Giddings never had

a numbered interlocker despite gaining an additional rail line in 1914

when SP built the "Dalsa Cutoff" northeast from Giddings to Hearne.

There was no interlocker at Round Rock because the I&GN / Katy crossing

there was grade separated. |

The Legislature passed

the Katy charter law on October 28, 1891 granting rights to the Missouri, Kansas

& Texas Railway of Texas, a newly created subsidiary of the parent Katy corporation.

It would be headquartered

in Denison and would own most of the Katy's current Texas rail lines, but not

the I&GN; Gould's delaying tactics had worked. The Legislature had soured on the idea of allowing the

out-of-state Katy corporation to own Texas' largest

railroad through an artificial Texas subsidiary that existed solely on paper. The Katy had little choice but to sell the I&GN back to Gould

for a paltry sum. The

end result was that Gould had financial control of the I&GN but no

involvement with the Katy. Unfortunately, Gould did not have much time to adjust

to this new reality; he died in New York in December, 1892. His son George

replaced him as President of the I&GN.

Newly freed from MP's

yoke, the Katy resumed construction east from Boggy Tank in 1892 and

reached Houston in 1893. There, it filed suit against the I&GN, claiming

ownership of the Galveston, Houston & Henderson (GH&H) Railroad which had the

shortest and most direct rail line

between Houston and Galveston. Gould had bought the GH&H in 1882 and assigned it to the I&GN

since the two railroads had worked cooperatively in Houston for more than a

decade. The

Katy argued that since it had owned the I&GN at the time, it was the rightful

owner of the GH&H. George Gould negotiated a settlement wherein the Katy and the

I&GN would each have 50% ownership of the GH&H and unlimited rights to operate

over it.

The Katy also completed the San Marcos - Smithville branch line

in 1892 by finishing the 36-mile track segment between Lockhart and Smithville.

Since the Katy was no longer a Gould railroad, it had to negotiate a trackage

rights agreement with the I&GN south from San Marcos to reach San Antonio, a

major population center the Katy wanted to serve. Several years later, the Katy

was forced by the Legislature to build its own set of tracks between San Marcos

and San Antonio. Legislators wanted to improve rail competition in the San

Antonio market so they added this construction requirement when the Katy sought

an unrelated charter amendment in 1899; the new track segment was completed in 1901.

Three years later, the Katy built a line into Austin that departed its main at Granger,

eleven miles north of Taylor, and proceeded southwest through Georgetown and

Round Rock. The Katy negotiated rights to use the I&GN main line from Austin to

San Marcos where it connected with the Katy's Smithville branch and the new

tracks to San Antonio.

Above: In 1903, the two

railroads collaborated to build Elgin Union Depot in the northwest quadrant of

the crossing, replacing an earlier wood structure. After passenger service to

Elgin ended in 1957, the depot sat vacant and then was converted for use by the

Elgin Police Department for thirty years ending in 1990. After another vacant

period, the building reopened in 2002 hosting the

Elgin Depot Museum

operated by the Elgin Historical Association. This view looks north along the

Katy. (Dave Ingles photo, 2012)

|

The 1886-1887 TB&H construction at

Elgin had crossed the H&TC at grade. By law, all trains were required to

stop before proceeding over any crossing diamond. This didn't have much

impact on trains through Elgin since the passenger and freight depots

were located close to the crossing, i.e. virtually all trains would be

stopping anyway. In 1901, a new law tasked the Railroad Commission of

Texas (RCT) to begin regulating safety systems for crossings of two or

more railroads. RCT had been created ten years earlier at the insistence

of the new Governor, Jim Hogg! Jay Gould's nemesis had been elected to a

higher office in 1890. Regulations issued pursuant to the 1901 law required railroads to

employ RCT-approved interlocking systems at crossings so that trains

could operate safely while avoiding unnecessary stops. On June 5, 1902,

RCT ordered 57 specific crossings to be interlocked within a year, but

Elgin was not among them.

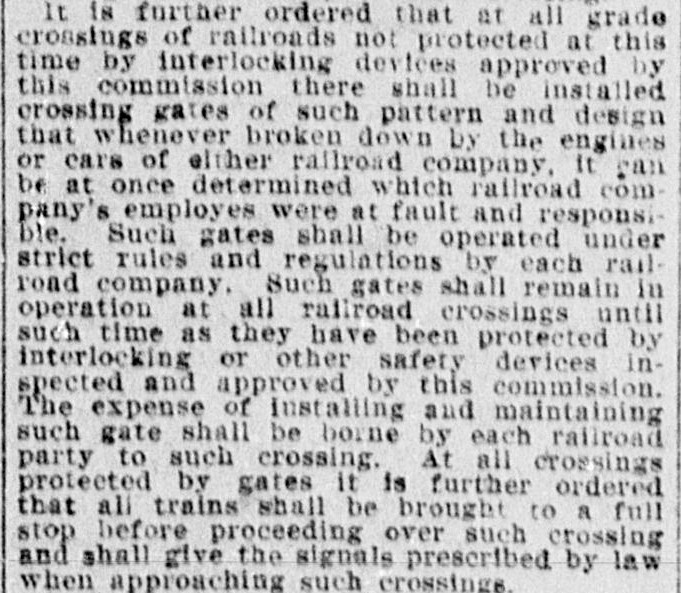

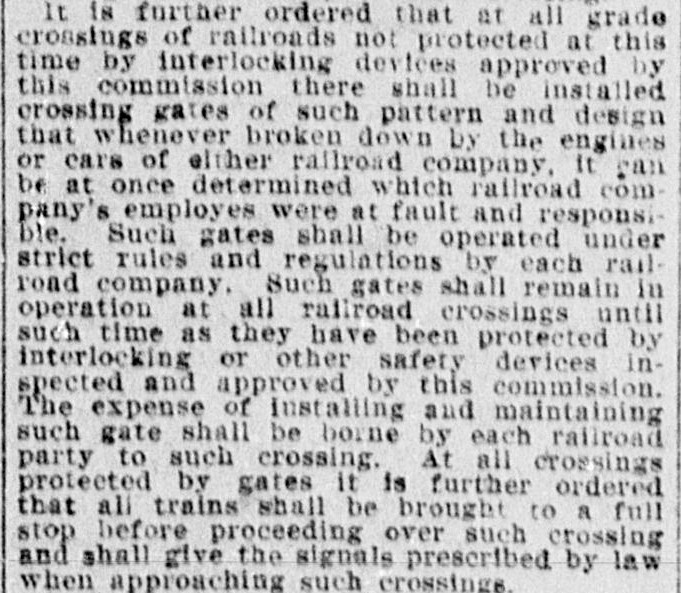

Left: The Houston Daily

Post of June 6, 1902 carried RCT's order in full, including

this paragraph requiring gates installed at all grade crossings. Oddly, the

order instructs that gates were to be designed primarily as a tool for investigating which

railroad crashed into a gate! The order plainly required that, despite

the presence of gates, "...all trains shall be brought to a full stop

before proceeding..." Hence, there was little incentive for railroads to

spend money to install gates other than fear of RCT action for

non-compliance. Since all trains stopped anyway, gates had limited

positive impact on crossing safety. Railroads complied, albeit slowly in

many cases. When necessary, train crewmembers would disembark to swing a

gate across the other track and latch it to the opposite gatepost. Where

a track with infrequent traffic crossed a busy one, the gate would be

opened to allow passage and then returned to its normal position against

the lightly used line. At some point, trains began to approach gated

crossings at restricted speeds such that a full stop could be made if a

gate was observed to be closed, but the train could otherwise proceed

without stopping. It is unclear whether RCT ever authorized

"restricted speed" approaches. Permission may have evolved after the Interstate

Commerce Commission (ICC) gained greater responsibility for railroad

regulation in 1920. |

The objective of the 1901 law was to foster widespread

deployment of electromechanical interlocking technology incorporating trackside

signals and derails, devices that had long been used in other states. The new

regulations required RCT approval of the interlocking design at each

crossing, including a final inspection by RCT before the installed system could

become operational. RCT decided to adopt a numbering scheme for interlocking plants.

A number typically was assigned when a railroad began corresponding with RCT

during the design phase. Thus, interlocker numbers generally followed the

chronology of when tower plans were instigated, but they do not precisely

reflect the timing of when interlockers were commissioned for operation; some

towers simply took longer to implement. The first

to follow this process, Tower 1 at Bowie, was

commissioned for operation on April 17, 1902.

|

Over the years, RCT continued to order specific

crossings interlocked. Railroads could request a hearing to discuss or

dispute the need and offer pertinent testimony. Railroads sometimes solicited permission to interlock a crossing, but they often just waited

for RCT to act.

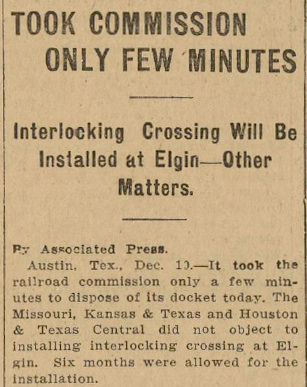

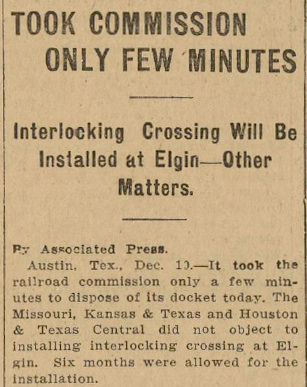

Left: RCT's order for an

interlocker at Elgin was announced verbally at a morning hearing on December 10, 1912

and reported that same evening in the

Galveston Tribune.

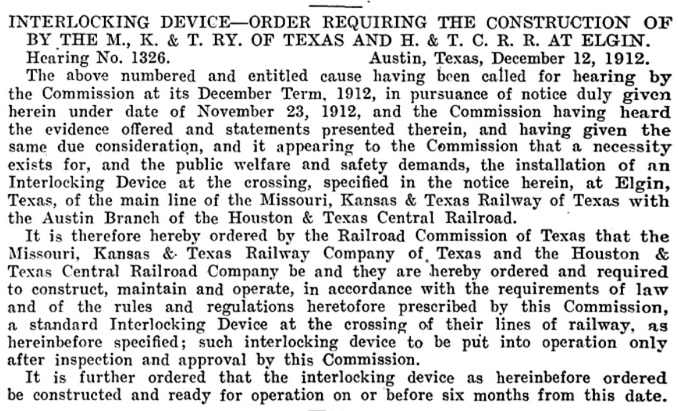

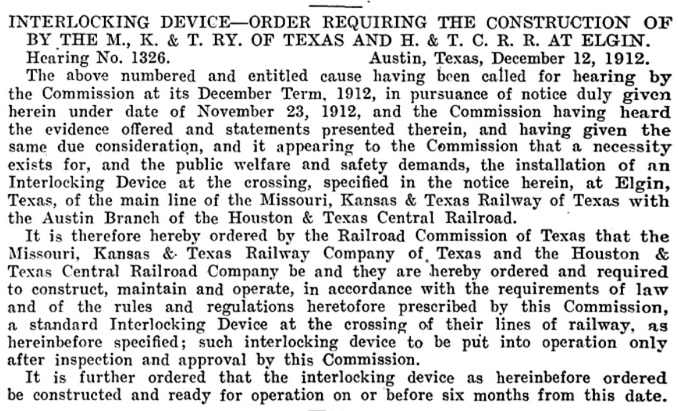

Right: RCT's order (issued 12-12-12) allowed six months for the interlocker

at Elgin to be installed.

It ultimately took fourteen months for

Tower 100 to open, on February 7, 1914. (RCT 1913 Annual Report) |

|

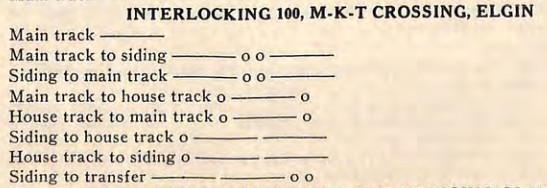

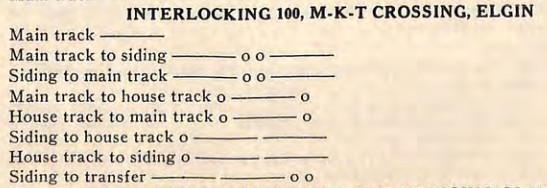

According to a table published annually by RCT, the

interlocking plant at Tower 100 was a mechanical type that initially hosted 29 functions.

This was substantially more than the normal minimum (twelve functions) indicating that the tower controlled

additional signals, derails and switches

for sidings and exchange tracks. The number of functions implemented by the

Tower 100 interlocker varied somewhat over the years, culminating with a function

count of 35 in the table published at the end of 1930 (after which RCT ceased

publishing an annual comprehensive interlocker table.) Beginning in 1915 (and in

subsequent years), RCT's table reported that SP

had the responsibility for operating Tower 100. SP probably had the additional responsibility

for tower and interlocker maintenance, as this was commonly coupled with

operational staffing. Recurring operations and maintenance (O&M) costs, e.g.

labor, materials and utilities, would

have been shared with the Katy using an agreed formula, typically the ratio of each railroad's

assigned interlocker functions compared to the total function count. At simple

crossings, this was usually 50 / 50, but an interlocker with 29 functions was

not simple; the precise expense split for Tower 100 is undetermined. It did not

take long for Elgin residents to learn which company employed the tower operators,

hence it was known as "the SP tower" around town. The Elgin Courier

of May 28, 1942 reported on the opening of a new Western Union office downtown

by reminding its readers that ... "After

5:30 pm each day messages are taken at the S. P. tower as here-to-fore."

That SP had staffing responsibility is no surprise because in the vast majority

of cases, the company that took the lead on designing and erecting a tower

also took responsibility for O&M staffing. And there is no doubt that Tower 100

was designed by SP. The exterior architecture matches that of virtually all

SP-designed towers in Texas, e.g. Tower 81,

Tower 95, Tower 115

and many others. A railroad would typically stay with a common architecture and

interior arrangement for the towers it designed. This reduced non-recurring

design expense by reusing specific features, with the added bonus that tower familiarity facilitated

easier movement of personnel among multiple sites for temporary staffing support. Since the tracks at Elgin

existed prior to 1901, RCT regulations required the two railroads to share

equally the capital cost of the tower and its interlocking plant.

|

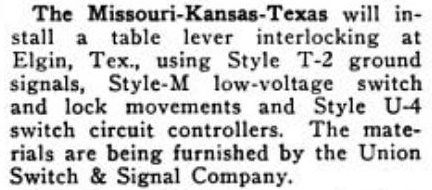

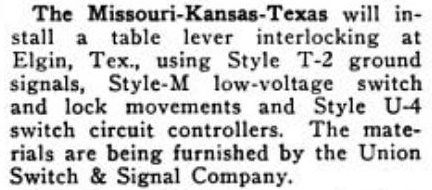

Right: The January, 1928 edition of

Railway Signaling reported the Katy's plan to install a

"table lever interlocking" at Elgin. This type of interlocker

was based entirely on electric relays,

avoiding the need for large "armstrong" levers that mechanical interlockers

used for manipulating trackside devices. The frame for the control

machine would be small enough to be installed on a table where the

operator sat. The Katy taking the lead for this modification may

indicate that it had instigated the upgrade or ... perhaps the Katy was

responsible for Tower 100 maintenance and

engineering, at least as of 1928. RCT listed SP as responsible for tower operations

through its final report in 1930, but a split arrangement to staff operations and maintenance was certainly allowable, though

uncommon. |

|

|

Left: SP's

employee timetable for its Dallas and Austin Divisions dated September

3, 1944 contained this table of whistle codes applicable to Tower 100.

Whistle codes provided a means for locomotives to signal the

tower to request specific switch and signal alignments.

The July 20, 1958 Katy employee timetable lists the Tower 100 interlocker as automatic, but the preceding March 1, 1957 Katy timetable

does not. This suggests that the conversion to an automatic interlocker occurred between those dates.

Manual override controls for the Elgin automatic interlocker are located

in the boxes atop the white trackside post to the far right in the Union Depot

photo above. |

This excerpt from an article by Lisa Johnson (hat tip Ann Helgeson)

in the Bastrop County Times of May 4, 1978

recounts an interview with

Mrs. W. M. Griffin of Elgin who provided her recollections of tower operations.

Her family had moved to Elgin in 1908 and she recalled seeing gates at the crossing as a young

child.

Mrs. W M Griffin, wife of the telegraph operator Bill Griffin,

remembers those early days. "We moved into town when I was a

little girl, in 1908, and I remember the big red depot as being

brand new. My father was with the cotton oil mill, and like a

lot of families, we moved to Elgin because the railroads made

it a center of activity and business." Mrs. Griffin's late husband operated the semaphore for the

Southern Pacific out of the little telegraph tower which was

moved to Avenue F from its original site adjacent to the Union

Station. She remembers that before the telegraph came, crossing

gates were used to regulate the trains where the KATY and SP lines

crossed. There were always three shifts or "tricks" for the

telegraph operators so that someone was always looking there

to give signals to the switchmen and avoid a collision. Griffin

was first trick (7 am to 3 pm), H G Davis whose wife, Sadie Bell

still lives in Elgin, was second trick (3-11 pm) and N R Radtke

was third trick, the night shift (11 pm - 7 am). Radtke started

with the SP in 1930 as a telegraph operator and retired in 1963

as a freight agent, a job that he took in 1957. "When I first

came to Elgin we had a switching tower and we worked for both

trains. During the War years, there was a great shortage of men

who could do the job that had to be done, so we trained young

men who hadn't gone to the service as telegraph operators. I guess I must've trained 50 or so during that time." Radtke said that for most of his working years, it was a

"...24-hour

job, seven days a week. There was not time off, someone always

had to be there." When Radtke started, there were no diesels.

He remembered the changeover. "It was a gradual transition

to diesel about 30 years ago. I remember General Electric, out

of Philadelphia, loaned the Katy two diesels, and they wore them

slap-dab out running them so much."

Asked if he had ever experienced a train wreck in his years with

the railroad he indicated there were many collisions for a variety

of reasons. Once a freight train coming south and an empty train coming

north from Camp Swift collided. Another particularly bad wreck

he remembered occurred between some gravel cars that had rolled

three miles out of a side track onto the main track. The engineer

of the oncoming train and his son were killed. Radtke estimated

he has seen 50 or more wrecks.

In 1915, the Katy entered a receivership that lasted

until 1923. It emerged from bankruptcy with a slight name change, the Missouri - Kansas - Texas Railroad,

hence M-K-T, MKT and MK&T have all been used as acronyms for the Katy. The Katy

remained independent into the 1980s, but by then it had been struggling to

sustain its existence for many years. In 1989, it was acquired by Union Pacific

(UP) and merged into MP which had become a UP subsidiary in 1982. The merger of

the Katy into MP was one hundred years after MP's lease of the Katy had been

terminated by the Texas Supreme Court. And as before, all operations were

conducted under the MP name.

| Right:

The Union Depot is clearly visible in this 1959 image ((c)historicaerials.com),

but is the tower located across from it? The photo at the top of the

page and another below shows that the tower was located close to the

diamond and that there were no structures on its east side. But this

image shows what appears to be a light color equipment cabinet casting a shadow to the north

located a short distance east of the crossing. It's unclear precisely what is

visible at the east corner of the

diamond. Perhaps it's the tower in a state of being dismantled for

relocation? An automatic interlocker was installed to replace the tower sometime between

March, 1957 and July, 1958. |

|

In August, 1961, SP requested permission from the

ICC to abandon the tracks between Hempstead and Brenham

knowing that the Brazos River bridge would not survive the next flood and that rail

traffic on the line was insufficient to justify rebuilding it. The tracks were embargoed the following month due to floodwaters caused by Hurricane Carla

and then officially abandoned between Hempstead and Brenham in 1962. The next

phase of abandonment was between Brenham and

Giddings in 1979. ICC approved the request as there was no traffic moving regularly

over the tracks and both endpoints retained rail service on other lines. In

1986, SP sold the tracks between Giddings and Llano to the City of Austin which

wanted to preserve the right-of-way for a potential commuter or light rail line.

The City leased the line for continued freight operations to RailTex, which established a new Austin & Northwestern to be the

operating railroad. In 1996, the Longhorn Railroad took over operations on the

line with freight service beginning May 6th. Yet another operating change was

made in April, 2000 when the City leased the line to the Austin Area Terminal

Railroad. The line has been

operated since October 1, 2007 by the Austin & Western Railroad (AWRR), a

subsidiary of transportation services company Watco. East of Austin, AWRR serves businesses in Manor, Elgin and Giddings.

Elsewhere, SP had maintained a robust presence throughout Texas,

continuing into the 1990s. Industry-wide consolidations forced SP to acquiesce

to a merger with UP in 1996. Within a couple of years, all operations in the UP

system were being conducted under the UP name; operationally, MP and SP ceased

to exist.

|

Left:

undated photo of Tower 100 and Elgin Union Depot (James E. Hassell collection)

Below:

Tower 100 was relocated to Avenue F near Booker T. Washington Elementary

School, not far from the Katy tracks and within a half mile of the

crossing. Unfortunately, it was allowed to fall into complete disrepair

and was ultimately razed, probably in the late 1980s. This photo at its Avenue F location

appeared in the Bastrop

County Times on May 4, 1978. (courtesy Ann Helgeson, Elgin Historical

Association and Elgin Union Depot Museum)

|

Above: two photos

of Tower 100 at its Avenue F location (Con Sweet photos, March, 1984) |

Above: Tower 100's

foundation (Ann Helgeson photo) |

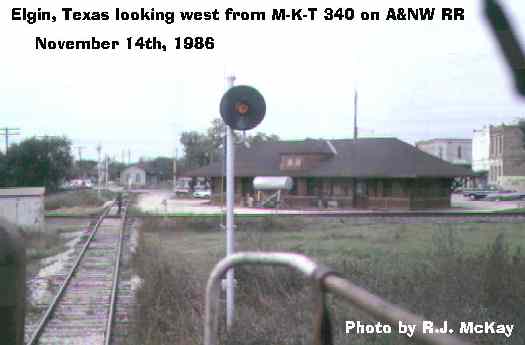

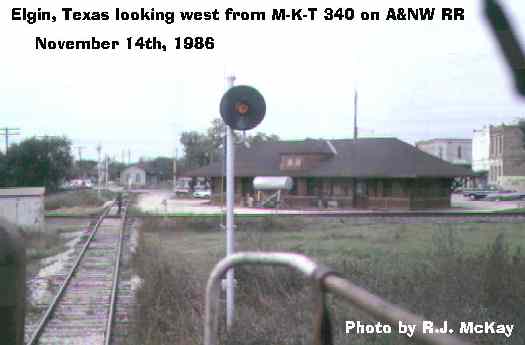

Right: R.J. McKay writes:

"Well, here's a latter

day picture of Elgin from when I worked on the Austin and Northwestern

Railroad.

I was the Engineer and Lanny Farley was the Conductor, both known

as TranSpecs, or Transportation Specialists on the RailTex properties.

Tower 100 was replaced with a signal box and on the opposite

side of the track are the time release boxes, one for the AUNW

and one for the Katy. Old H&TC Freight depot on the

left in the background and the Union Depot on the right." |

|

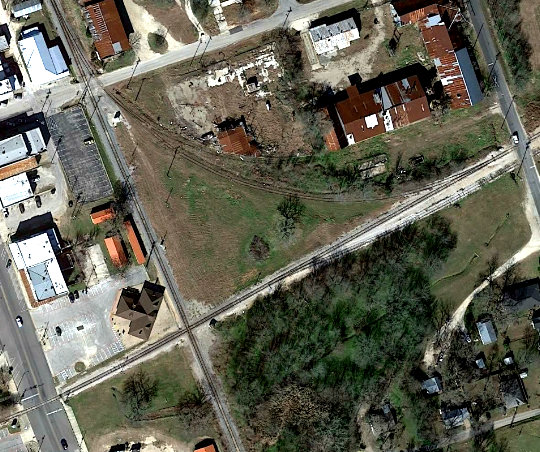

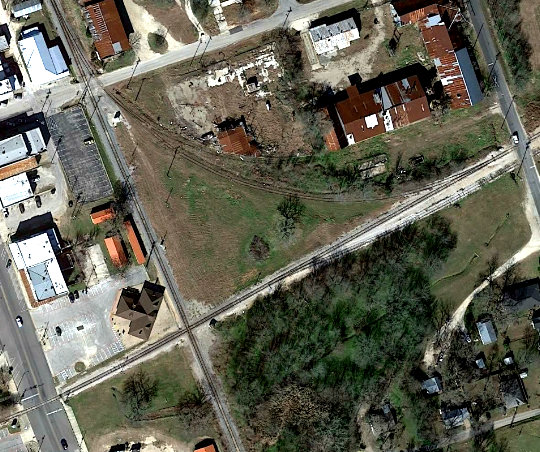

Above Left: This Google

Street View image from June 2016 shows an automatic interlocker cabin in the southeast quadrant of the diamond

where Tower 100 once stood. The interlocker

override controls are on the post across from it in the northeast quadrant. Above Right:

The Tower 100 crossing is near the center of Elgin on the southeast corner of

downtown. This 2022 Google Earth satellite view shows the former Katy tracks

intact generally north / south and the former SP tracks intact generally east /

west, with a connecting track in the northeast quadrant. A track chart of Elgin c.1920

produced by SP (hat tip, Stuart

Schroeder) shows there was also a connecting track in the southeast quadrant,

but there is no evidence of it in the satellite image above. While both rail lines remain active, Federal Railroad Administration

grade crossing records show that in 2019, UP was operating an average of only two

trains daily on the former Katy tracks through Elgin which had been relegated to

secondary status. Grade crossing information from October, 2023 reported an

average of two trains per week on the AWRR through Elgin.

Although UP / AWRR traffic exchange is feasible at Elgin, the primary

interchange is at McNeil.

Below: These photos of a Tower 100

model built by Jim Zwernemann were taken at the

Katy House Bed & Breakfast in Smithville in August, 2006. Credit to Bruce Blalock for making the

arrangements. Thanks, Bruce! (Jim King photos)

Last Revised: 7/23/2024 - Contact the Texas

Interlocking Towers website.