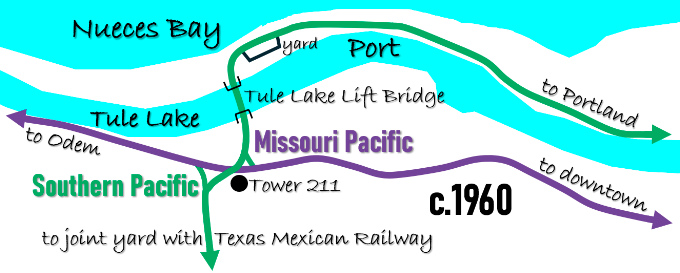

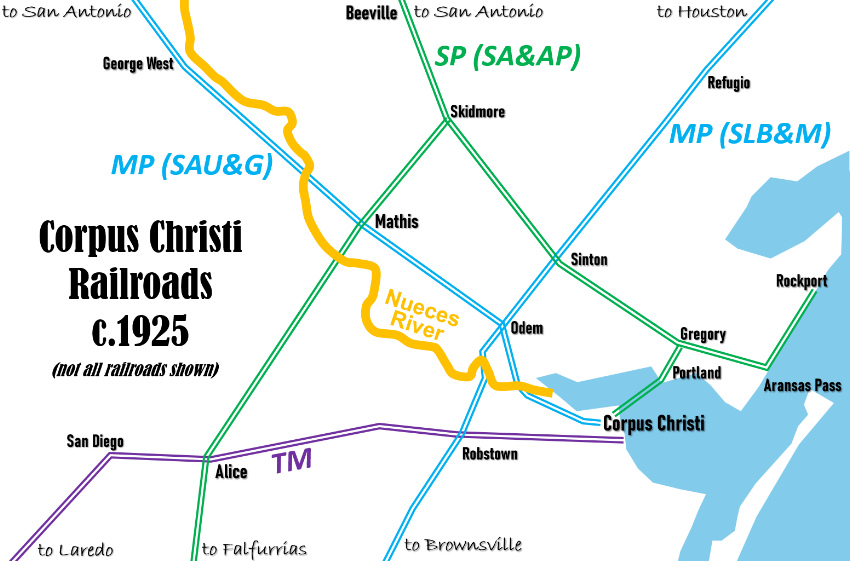

Crossings of the Missouri Pacific Railroad with the Texas & New Orleans Railroad (211) and the Texas Mexican Railway (197)

|

Left:

Carl Codney took this 1998 photo of the Tower 211 automatic interlocker

cabin in Corpus Christi; note the "211" barely legible on the black

placard at the roof's edge. Tower 211 was installed in 1959 about 0.4

miles south of the Tule Lake Lift Bridge which opened for rail and

vehicular traffic that October. Below:

The Southern Pacific (SP) and Missouri Pacific main lines between Corpus

Christi and San Antonio crossed at Tower 211. SP started using new

Port-owned tracks over the Tule Lake Lift Bridge when the SP line into

downtown across the entrance to the Port was removed to widen the ship

channel. |

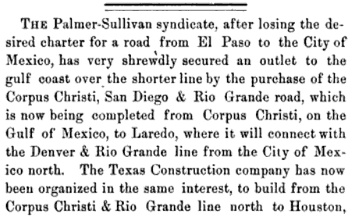

The earliest railroads in Texas were dependent on ports along the coast to receive construction materials, particularly rails from east coast mills. Wagon roads into the interior of the state were not suitable for hauling heavy cargo. Thus, the earliest railroads literally built out from ports hauling rails and other materials over newly laid tracks to forward construction teams using locomotives and railcars that had also been received through the port. One such railroad was the Corpus Christi, San Diego and Rio Grande (CCSD&RG) Narrow Gauge Railroad chartered in March, 1875 to build west from the port at Corpus Christi to the Rio Grande River. The destination was the border towns of Eagle Pass and Laredo by way of the community of San Diego. Corpus Christi did not have a deep water port, so the ships carrying iron rails for the CCSD&RG very likely tied up at offshore locations along Mustang Island and had their cargoes lightered into Corpus Christi in shallow draft boats. The CCSD&RG and the other railroads that followed helped to stimulate local commerce and grow Corpus Christi's population. Growth in turn led to the eventual construction of a deep water port; serving the port became a profitable business for the railroads.

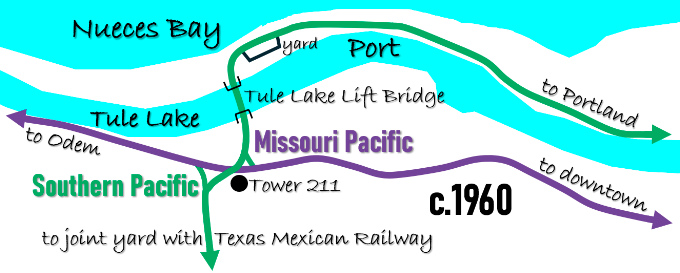

Right: The CCSD&RG was chartered in March, 1875.

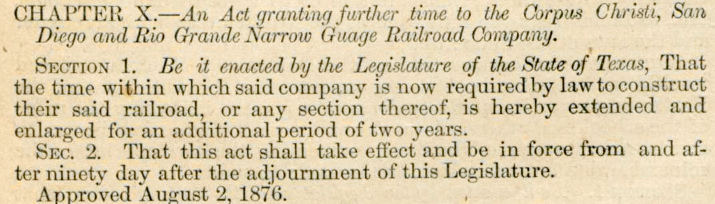

This item from the

Houston newspaper The Age

dated August 16, 1875 noted that the CCSD&RG had established its headquarters in Corpus

Christi, led by Uriah Lott. Lott was a native of New York who had made

his way to Corpus Christi at age 25 to get into the freight forwarding

business. He soon had his own company and by age 30 was earning his

fortune shipping wool and other commodities to New York on

vessels he chartered. Lott's interest in improving and expanding

the port at Corpus Christi led him to take on the task of building a railroad

from the port to the major Mexican trade gateways on the Rio Grande River. Though the project took several

years and its charter needed a time extension by the Legislature (below),

the railroad finally succeeded in reaching Laredo

in 1881 (but it was not extended to Eagle Pass.) from Special Laws of the State of Texas passed at the Session of the Fifteenth Legislature (Portal to Texas History) |

|

The CCSD&RG operated its first excursion train --

mostly for publicity to drum up additional investment -- on December 18, 1876.

The trip went eighteen miles from Corpus Christi and returned. Additional grade

was ready and track laying soon reached 25 miles from Corpus Christi, enough

that Lott was able to inaugurate regular excursion trains on January 1, 1877 to the small community

of Banquete. Construction proceeded no further for all of 1877 due to inadequate funds.

The publicity (and tiny fares) from the excursions was not filling Lott's

coffers. He was finally able to resume construction in 1878 with the financial

assistance of Richard King and Mifflin Kenedy. King and Kenedy were experienced

steamboat pilots who had met in 1842 while handling riverboats for U.S. forces

during the Seminole Wars in Florida. They subsequently teamed up in Texas to form a

steamship company operating on the Rio Grande. Acquiring land with their

profits, they became active in ranching, with King founding the famous ranch

that bears his name and Kenedy acquiring the vast Laureles Ranch 22 miles south of Corpus

Christi. Knowledgeable of the need for improved inland transportation options in south

Texas, King and Kenedy helped to keep the CCSD&RG afloat, enabling Lott to complete 27

additional miles very slowly, finally reaching San Diego in September, 1879.

In the next 12 months, Lott completed 43 more miles to a place he called Mesquite (where the town of

Hebbronville was founded three years later.) At this point, 95 miles from Corpus

Christi, Lott elected to stop construction

in hopes of luring a bonus from the citizens of Laredo, pretending he had

other options for continuing his route. Laredo knew better; it had 3,500

residents -- vastly more populous than any other river town between Brownsville

and El Paso. It was also the

well-publicized destination for the International & Great Northern (I&GN)

Railroad, Texas' largest, which was being built south from

San Antonio by rail

baron Jay Gould.

With two railroads approaching, Laredo had begun to grow rapidly (its population

would more than triple between 1880 and 1890.) Adding to the growth in commerce,

Laredo had been named the Rio Grande River crossing location for the Mexican

National Railway to Mexico City to be built by the New York based Palmer -

Sullivan syndicate. The syndicate was led by General William Jackson Palmer, a

man with railroad credibility having been the surveyor for the Kansas Pacific

Railway, the President of the Denver & Rio Grande Railway, and recently named

President of the Mexican National Railway. Rather than relying on a bonus from Laredo that

would not be forthcoming, Lott, King and Kenedy decided to sell the CCSD&RG to the Palmer -

Sullivan syndicate. When they succeeded in doing so in the spring of 1881, the new

owners promptly changed the name to the Texas Mexican (TM) Railway. They completed the

remaining 59 miles

into Laredo in early September, 1881, three months before the I&GN reached town.

In November, a railroad bridge over the Rio Grande River opened to connect the

TM with the Mexican National Railway.

|

Left: Railway Age, December, 1881 With new owners, the TM had moved aggressively to announce great plans for expanding their narrow gauge network in south Texas. In response to these pronouncements, as early as May, 1881, the City of Galveston began trying to induce the TM to build there by offering various incentives. In an interview with Gen. Palmer in the Galveston Daily News of May 3, 1881, Palmer claimed already to be building a narrow gauge line between Houston and a TM junction at San Diego under the charter of the Houston East & West Texas (HE&WT) Railroad. The line would run "...from Houston to Richmond, thence to about six miles north of Wharton to Victoria, thence to Goliad, Beeville and San Diego." The HE&WT was a narrow gauge line that had commenced building from Houston toward Shreveport in 1877. According to Palmer, ... "In a very short space of time there will be a continuous line of narrow-gauge road from New York City to the City of Mexico." Connecting to the HE&WT on the north side of Houston would require a right-of-way through the city. The Galveston Daily News of September 21, 1881 reported that in response to a letter from TM's Chief Engineer, the Houston City Council passed an ordinance offering a detailed right-of-way through Houston along with specific terms and conditions regarding construction, maintenance and operation, requiring a first class narrow gauge railroad connecting to TM's existing Corpus Christi - Laredo line. But railroad talk was always big; none of the TM's ambitious plans ever proceeded beyond the planning stage. |

The "real" TM remained focused on the profitable

business of moving passengers and freight between Laredo and Corpus Christi. Not

only was business good, there was so little need to exchange cars with other

railroads that the TM didn't convert to standard gauge until 1902. Most other

narrow gauge lines in Texas (excepting lumber trams) had converted by the mid

1890s.

Benefitting financially from the sale of the railroad, Lott became a sheep

rancher and promptly lost all of his fortune. His next venture was to build a

railroad between the coast and San Antonio, Texas' second largest city (after

Galveston.) As S. G. Reed explains in his reference tome

A History of the Texas Railroads (St. Clair

Publishing, 1941), Lott expected financial...

"...support from San Antonio, also from Corpus

Christi, Rockport and Aransas Pass. These three towns on Corpus Christi Bay were

then vieing (sic)

with one another to secure Government aid as a deep water port, but they were

united in the need for a railroad to San Antonio."

By then, San Antonio had already experienced its first rail service

and wanted more. The

Galveston, Harrisburg & San Antonio Railway (GH&SA) had...

"...reached

there in 1877, but that city still wanted rail connection with a nearer port

than Galveston."

Prior to Lott's involvement, the effort had begun with

a committee of San Antonio citizens researching the "best" nearby Gulf port to

which a railroad could be built. The consensus quickly moved toward finding

a location near Aransas Pass, probably Rockport. That community had been established in 1868 when King, Kenedy and the Coleman - Fulton

Pasture Co. built a slaughterhouse there and contracted with the Morgan

Steamship Co. to ship tallow and hides on a regular basis. In this era before

electromechanical refrigeration, south Texas cattle ranchers had more cattle

than they could profitably sell, so they began processing excess cattle simply

for their tallow and hides, dumping the beef into the ocean or feeding it to

hogs. The Federal government had secured ten feet of water

depth at Aransas Pass and Congress had allocated another $100,000 which the

government's engineer claimed would be sufficient to extend the depth to 18 feet.

The committee also considered Corpus Christi and an area near Matagorda Bay

where Port O'Connor was eventually settled. Field trips were made and ultimately, a group of ten San

Antonio businessmen incorporated the San Antonio & Aransas Pass (SA&AP) Railway

to build from San Antonio to the coast. In his book

Uriah Lott (The Naylor Co., 1949), author J. L. Allhands describes a

nuance in the charter of the SA&AP. The charter called for construction of ...

"... a line of road between San Antonio and a terminus at some point on or near Aransas Bay in the County of Aransas. That charter was later amended to read: "into and through the County of Nueces to Aransas Pass."

The nuance in the amendment was that Nueces County and

its county seat of Corpus Christi sat entirely south of Nueces Bay while Aransas

County is well north of Nueces Bay, on the other side of San Patricio County

which forms the bay's northern border. Effectively, the amended charter called

for building through Corpus Christi to reach a mainland point across from

Aransas Pass, about 18 miles northeast of downtown Corpus Christi where the town

of Aransas Pass now sits (in San Patricio County.) This amendment would appear

to have Lott's fingerprints all over it. Lott was not an investor --

he had no money since his sheep ranch had gone bust -- but he had railroad

credibility from his work leading the CCSD&RG. Lott had been

involved in the planning and he would take the reigns as President of the SA&AP in March, 1885.

As he had done with the CCSD&RG, Lott organized an excursion as soon as it

was feasible. In January, 1886, a train carrying 800 (!) people went to

Floresville for a big celebration. Construction proceeded so quickly that by

June, work trains had reached Beeville, an established community and the county

seat of Bee County about 45 miles north-northwest of Corpus Christi. At that point, had Lott intended to build through the

County of Nueces to reach Aransas Pass, he would have adopted a nearly due

south heading to cross the Nueces River west of where it empties into Nueces

Bay. South of the river, the railroad would have turned southeast to enter

Corpus Christi and proceed into downtown. From there, it would turn northeast to cross Rincon Channel between Nueces

Bay and Corpus Christi Bay, heading for Rockport. Lott knew this was an

inefficient way to reach Rockport which was still a major consideration for the

SA&AP. Instead, he chose a 150-degree heading out of Beeville into San Patricio

County, turning slightly eastward to a 120-degree heading where the rails

crossed Chiltipin Creek (the future site of Sinton, now the county seat of San

Patricio County.)

This route placed the rail line north of Nueces Bay, on

the opposite side from Corpus Christi. The straight line 120-degree route past Chiltipin Creek brought the SA&AP

closer to the Nueces Bay shoreline as each rail was laid. After fifteen miles, the SA&AP was

about six miles inland from the narrowest part of Rincon Channel. This location was christened

Corpus Christi Junction from which Lott built a spur to the southwest across the

channel and into Corpus Christi in

October, 1886. The main line would continue on the same 120-degree heading out

of Corpus Christi

Junction for another seven miles and then make a 90-degree curve to the northeast to

reach Rockport fourteen miles away. The 21 miles to Rockport was completed two

years later but it was never the main line. Lott knew that the

burgeoning commerce in Corpus Christi would lead to demands for continued

improvements to its port leading to much greater traffic with San Antonio than

Rockport could ever deliver. By 1890, Corpus Christi had four times the

population of Rockport.

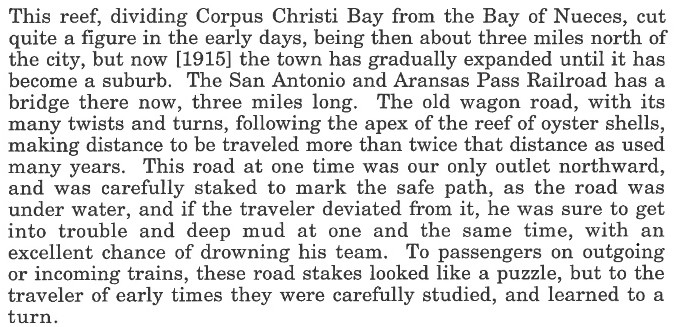

Lott and the Coleman - Fulton Pasture Co. agreed

to build a town surrounding Corpus Christi Junction, named for U.S. Attorney

General Thomas W. Gregory. With rails to Corpus Christi, Rockport and San

Antonio, Gregory prospered. The spur to Corpus Christi required a 90-degree

southwest turn from the SA&AP main line at Gregory. There was about six miles of

land and three miles of water to reach landfall in Nueces County. Lott knew that it was feasible to cross Rincon Channel with

a 3-mile trestle because it was

notoriously shallow water, so shallow that a winding

reef road

across the bay, known simply as "El Rincon" ("the reef"), had long been used by coastal

travelers following known beds of

oyster shells. During low tide, the water depth over the beds was typically less

than two feet, able to support horse and wagon travel ... but only for those

able to follow the beds. A 1997 study for the Corpus Christi Bay National

Estuary Program by the University of Texas Center for Research in Water

Resources included this 1915 quotation from a "Mrs. Sutherland"...

In 1891, land developers opened a new town on along the

SA&AP three miles southwest of Gregory. The town bordered both Corpus Christi

Bay to the southeast and Nueces Bay to the southwest, and became known as the

point of departure for the SA&AP's lengthy trestle across Rincon Channel. The

town was named Portland because one of the participants in the land development

was the Portland Harbor and Improvement Co., a company based in Kansas.

Having completed its line to Corpus Christi (and with the extension from

Gregory to Rockport in work), the SA&AP began building

additional lines in south Texas, including a line to

Houston and another toward Waco. Lott hired a young man, Benjamin Franklin Yoakum, to the position

of Chief Clerk for the SA&AP. Yoakum quickly advanced

to the ranks of senior management, becoming General Manager by 1888. The

new construction caused the SA&AP to become financially overextended, and it went into receivership in the summer of 1890. Yoakum was named to be one

its two Receivers by the bankruptcy court (the other Receiver was an I&GN

executive.) In 1892, Yoakum supported a plan by Southern Pacific (SP) to assist

the SA&AP in coming out of bankruptcy. SP had tracks from Los Angeles to San

Antonio and saw Corpus Christi as another Atlantic port option for west coast

commerce using the SA&AP's line to

reach it (railroads provided a land bridge for west coast imports and exports

because the Panama Canal wouldn't open for another twenty years.)

SP preferred to buy the SA&AP, but the Texas Legislature would

never have granted permission

since SP controlled the GH&SA, a direct competitor to

the SA&AP in the San Antonio - Houston market. Unable to own the SA&AP, SP finessed the issue by

proposing that a real estate company affiliated with SP's founders purchase

80% of the SA&AP's stock. The remaining 20% would be held by Mifflin Kenedy, to

whom the SA&AP was substantially indebted. SP was also willing to back new

SA&AP construction bonds,

which would greatly improve the market for those bonds. The bankruptcy court signed

off on the plan which Yoakum had helped negotiate. The new Railroad Commission of

Texas (RCT) did not object to the plan. RCT had just been created by legislation in 1891, so it

was not ready to assert its executive authority despite some potentially

questionable aspects of the plan. As numerous "SP men"

moved into the ranks of SA&AP management, the SA&AP began operating -- de facto if not

de jure -- under SP's control. His Reciever job complete, Yoakum moved on

to become a Vice President of the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe Railway in Galveston

in April, 1893.

Ten years later, Yoakum became President and CEO of the St. Louis & San

Francisco ("Frisco") Railway, a major Midwest railroad based in St. Louis.

Soon thereafter, Yoakum began to focus on the Texas market he knew so well,

seeking export outlets for the Midwest commodities his railroad carried.

In 1903, Uriah Lott approached his former protege Yoakum with a plan for

building to the Rio Grande Valley, an area of growing agricultural production

that was yet to be connected to the national rail network. Yoakum was

sufficiently intrigued to charter the St. Louis, Brownsville & Mexico (SLB&M) Railway and

hire Lott to be its president. Although Corpus Christi and Laredo were

both connected by rail with the rest of Texas, the TM line between them was the

southern boundary of the national rail network. The few railroads that existed in the

Lower Rio Grande Valley operated solely within that area.

A race began with the

objective of connecting the Lower Rio Grande Valley to the national rail network.

The SLB&M was Yoakum's entry; SP's entry was a line that the SA&AP had begun

building south from Alice, a town served by both TM and the SA&AP about forty

miles west of Corpus Christi. The race ended quickly in 1904 when an

investigation by RCT determined that SP had illegally obtained direct possession

of a controlling interest in SA&AP stock. Though SP accused Yoakum of

fomenting the investigation through his close friendships with the

Commissioners, it nonetheless admitted guilt and agreed to sanctions

that included losing its SA&AP stock and being unable to back new SA&AP bonds. The SA&AP

construction stopped abruptly at Falfurrias, 67 miles shy of the Valley, and

remained there for

more than twenty years.

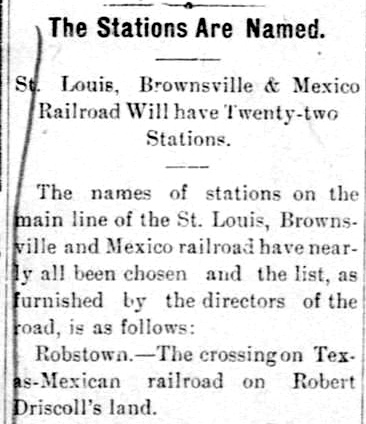

Left:

The

Brownsville Herald of July 2, 1903

published the names of the stations the SLB&M had recently announced

for the new line. The

first to be listed was Robstown, named for the landowner, Robert

Driscoll, where the SLB&M would cross the TM. Construction would

commence southward from Robstown because materials could be shipped there by rail.

Driscoll's son, Robert Driscoll, Jr., was a

Victoria native who had attended college at Princeton University and

had begun a law practice in New York. He was part of Yoakum's management

team that incorporated the SLB&M and he returned to the area in 1906 to

help his elderly father (died 1914) manage the family's sizeable landholdings

and other interests. Driscoll, Jr. became active in Corpus Christi

banking and he served as the Chairman of the Port of Corpus Christi

between 1926 and 1929. Left:

The

Brownsville Herald of July 2, 1903

published the names of the stations the SLB&M had recently announced

for the new line. The

first to be listed was Robstown, named for the landowner, Robert

Driscoll, where the SLB&M would cross the TM. Construction would

commence southward from Robstown because materials could be shipped there by rail.

Driscoll's son, Robert Driscoll, Jr., was a

Victoria native who had attended college at Princeton University and

had begun a law practice in New York. He was part of Yoakum's management

team that incorporated the SLB&M and he returned to the area in 1906 to

help his elderly father (died 1914) manage the family's sizeable landholdings

and other interests. Driscoll, Jr. became active in Corpus Christi

banking and he served as the Chairman of the Port of Corpus Christi

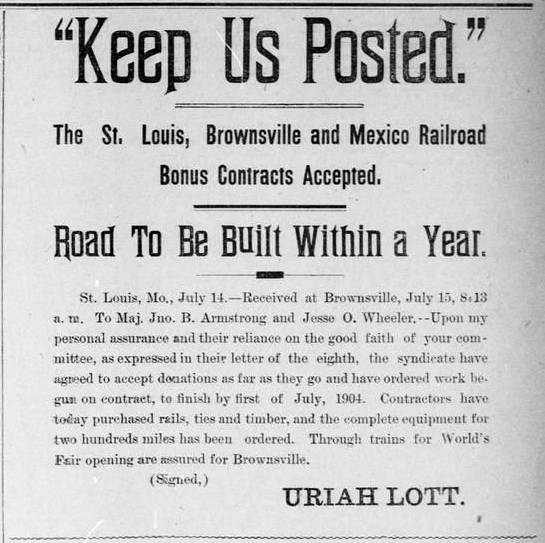

between 1926 and 1929.Right: Planning to build between Brownsville and Robstown, Lott posted this notice in the Brownsville Herald of July 15, 1903. With the SA&AP stalled at Falfurrias, the SLB&M provided the first connection from the Lower Rio Grande Valley to the national rail network when it completed its line between Brownsville and Robstown in 1904. From Robstown, TM's tracks both east and west led to SA&AP connections (at Corpus Christi and Alice, respectively) to San Antonio and elsewhere. The SLB&M's northward construction continued for several years, finally ending at Algoa (with trackage rights into Houston) in 1908. To serve Corpus Christi, the SLB&M asked the SA&AP for trackage rights from Sinton but was rebuffed. Instead, the SLB&M obtained rights into the city on TM's tracks from Robstown. SLB&M passenger trains began sharing the Union Depot at the original TM yard. The SLB&M operated profitably for many years but it never built tracks into Corpus Christi, its north / south main line remaining fourteen miles west of downtown. In 1925, the SLB&M came under the ownership of a major Midwest railroad, Missouri Pacific (MP). |

|

The next and final major rail line into Corpus Christi belonged to the San Antonio, Uvalde & Gulf Railroad (SAU&G, a.k.a "the Sausage".) The SAU&G had originated as the Crystal City & Uvalde Railroad in the far western reaches of south Texas, chartered in 1909 to build between those endpoints. Uvalde was a town on SP's Sunset Route west of San Antonio. Crystal City, 36 miles south of Uvalde, had been founded by wealthy land developers convinced it could be a "winter garden" for commercial vegetable production (and they weren't wrong; Crystal City still bills itself as the Spinach Capital of the World, complete with a statue of Popeye erected in 1937.) The initial success of the railroad brought ideas for expanding eastward from Crystal City to reach the I&GN tracks at Gardendale, the line built by Jay Gould between San Antonio and Laredo. The I&GN was a major Texas railroad, hence a connection would create competition for SP. Adopting the SAU&G name in 1912, the railroad continued building east beyond Gardendale to Pleasanton and then north to San Antonio in 1913. Unable to resist closing the 116-mile gap between Pleasanton and the Gulf coast, the SAU&G entered Corpus Christi in 1914, effectively creating a main line to San Antonio via Pleasanton.

|

Left: The

rapid expansion of the SAU&G in south Texas overextended its finances

and it went into receivership within six months of reaching Corpus

Christi. The receivership lasted until December, 1925 when the SAU&G

became owned by MP. MP then gave the SLB&M rights to use the SAU&G

tracks into Corpus Christi from their mutual crossing at Odem. The Transportation Act of 1920 terminated Federal control of the railroads which had been in place during the Great War. The Act mandated a study of the national rail network and it increased the power of the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to regulate railroads. Among many recommendations, the study called for the SA&AP to become part of SP's network. Despite State of Texas opposition, the ICC allowed SP to purchase the SA&AP in 1925, giving SP its own tracks into Corpus Christi. SP restarted the SA&AP's construction toward the Valley, reaching Edinburg in 1927. Throughout this timeframe, TM remained owned by the National Railways of Mexico. It continued to operate between Laredo and Corpus Christi, and it did not build additional tracks of any significance. |

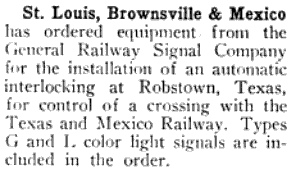

| As of 1925, RCT had yet to consider

requiring interlocking plants for any of the various rail crossings in

this region. The first to be installed was commissioned as Tower 159 in Mathis in 1929,

the last traditional manned, two-story interlocking tower built in Texas.

Much later, automatic interlockers at Sinton (Tower 193),

Robstown (Tower 197), and Corpus Christi (Tower 211) were installed, beginning

with Sinton in 1947. Right: The Signalman's Journal of March, 1951 carried this news item discussing the SLB&M's order of signals and equipment for an automatic interlocker to be installed at its crossing of the TM in Rosbstown. The crossings at Odem and Alice were gated, and Odem became fully interlocked in the early 2000s. |

|

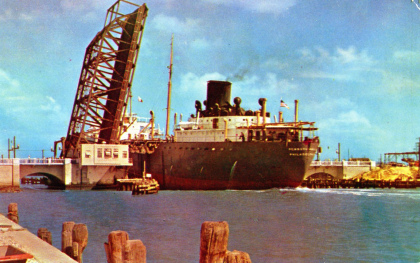

Recovery from the devastating

hurricane of

1919 motivated Corpus Christi civic leaders to seek development of a safe

harbor, deep water port. To do so, Nueces County voters authorized creation of

Nueces County Navigation District No. 1 in 1922 (renamed in 1981 as Port of Corpus Christi Authority of Nueces County, Texas,

more commonly just Port of Corpus Christi.) The new Port opened in

1926, carved out of

Halls Bayou which emptied into Corpus Christi Bay near downtown. The bayou was

small and had rail and street bridges over it, but the bridges were removed for

the widening of the bayou to

become the ship channel into the Port. To facilitate street

traffic and continued use of the SA&AP main line between downtown and the

trestle to Portland, the ship channel was spanned by a new bascule bridge (it was never given a formal name; everyone

knew it simply as "the bascule bridge".) The bridge was 52 feet wide

to carry both trains

and vehicles, and it was counterbalanced by a massive weight. The balancing was

so precise that the bridge could be rotated

to a height of 141 feet using two small electric motors.

A year after the

Port opened, SP began consolidating most of its Texas and Louisiana railroads

into its Texas & New Orleans (T&NO) Railroad subsidiary. The SA&AP was one of

the railroads to be consolidated. Under this plan, SP leased various railroads

to the T&NO in 1927 and then fully merged them in 1934 at which time the SA&AP

ceased to exist. As SP was preparing for the mergers into the T&NO, MP began a lengthy receivership

and

was operated under supervision of the bankruptcy court for more than two

decades. MP's receivership ended in 1956 at which time all of its Texas railroad

subsidiaries were merged into a single MP railroad including the SAU&G and the

SLB&M. SP took the same approach shortly thereafter, dissolving its T&NO

subsidiary in 1961 and merging the assets.

|

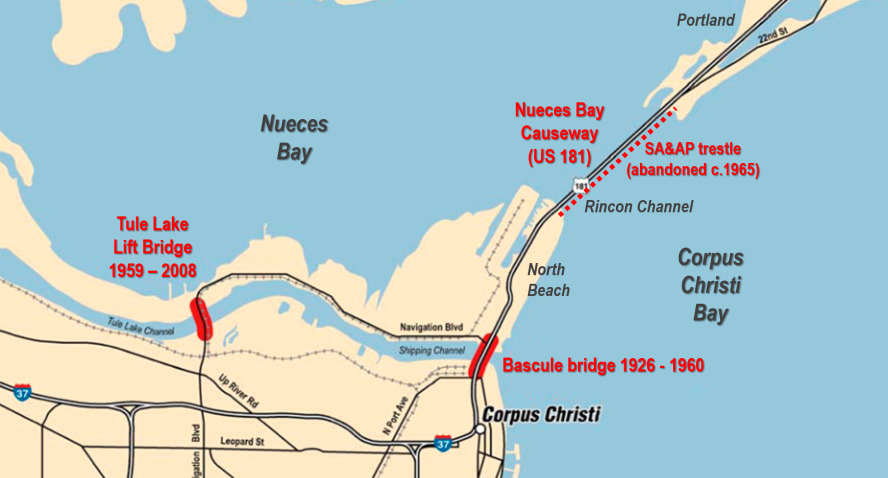

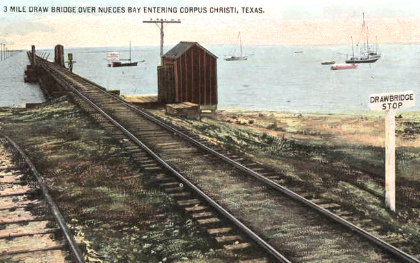

Right: Railroads into Corpus Christi have made

use of three major bridges. The SA&AP spur built into Corpus Christi in

1886 required a lengthy trestle with a draw bridge to cross Rincon Channel where Nueces Bay

flows into Corpus Christi Bay. The trestle was rebuilt after the hurricane of

1919. The present causeway (US 181) was built beside the trestle in 1950

and expanded to two parallel spans in 1963 for traffic in opposite

directions. Halls Bayou was widened and deepened to become the ship channel for the deep water port. The bascule bridge serving both vehicles and trains was installed at the entrance to the channel to facilitate continued use of the SA&AP tracks from North Beach into downtown. In the early 1930s, an expansion project extended the Port westward 1.5 miles. Another westerly extension to reach Tule Lake was authorized in 1938. On October 23, 1959, the Harbor Bridge opened serving vehicles only, literally overshadowing the bascule bridge. That same month, the Tule Lake Lift Bridge opened four miles to the west to connect the tracks to both sides of the Port. The Lift Bridge facilitated SP's access to its trestle to Portland since the bascule bridge (and the SP track over it) had to be removed to widen the ship channel. |

Above: Texas Dept. of Transportation Map, 2003, annotated |

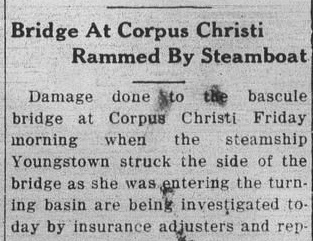

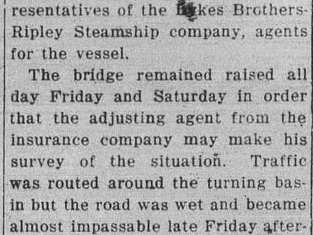

The impetus for the new Harbor Bridge was the "Bascule Bridge Bottleneck" that had fouled vehicular, rail and Port traffic for decades. Neither vehicles nor trains could cross while the bridge was raised (an average of 30 times per day!) hence slow-moving ships navigating the narrow channel could completely halt traffic for lengthy periods of time. The bridge foundation protruded into the channel, reducing the horizontal clearance for ships. This contributed to the problem of ships colliding with the bridge on many occasions, snarling traffic for lengthy periods.

| Right: The San Patricio County News (Sinton) of January 8, 1931 carried this story about the bascule bridge being damaged by a steamship. The bridge was out of commission for two full days while investigators and insurance agents surveyed the damage. Train and ship traffic was halted, and vehicular access between downtown and North Beach required a drive on an unpaved road around the Turning Basin. This drive became vastly longer as the Port was extended west several miles over the next two decades. |

|

|

|

The Port's published history explains the Bascule Bridge Bottleneck and the resolution of the problem...

No history of the Port would be complete without some detail of the Bascule Bridge and the removal of the "Bascule Bridge Bottleneck". When the Port was constructed in 1925, there was a small bayou at the entrance which was crossed by a two-lane highway bridge and the railroad bridge of the S.A & A. P. Railway (Southern Pacific). To permit the passage of large ships, a Bascule bridge was erected which had about 100 feet of horizontal width and 14 feet of vertical height above the water. This was adequate to handle the ships which were in use at that time. Fenders and timbers to protect the structures on the inside reduced it to about 98 feet in horizontal width. Of course, the bridge was "OPENED" when a ship approached. By the 1950's the volume of both ship and vehicular traffic had increased to such extent that there was an urgent need to break the "Bascule Bridge Bottleneck". Southern Pacific (SP) entered Corpus Christi from Portland via a trestle across the bay and via the Bascule bridge to/from its yard on the south side of the inner harbor channel. Incidental to removing the Bascule bridge two thing occurred: first the Tule Lake lift bridge was constructed to facilitate rail and highway access to/from the north side; second, the Savage Lane line was built to connect the Tex Mex yard on Agnes street to the north side via the Lift Bridge. Southern Pacific continued to operate to/from Portland and transited along the north side of the inner harbor channel to/from the Tex Mex yard. ... It wasn't until sometime in the 1970s that SP ceased accessing Corpus Christi from Portland. SP then worked out a deal for rights on Missouri Pacific (MP) to access Corpus Christi.

It appears that the Corpus Christi Terminal Association (CCTA), an entity created by the Port during the early years, was assigned the ownership of the track infrastructure built by the Port. The San Patricio County News story from 1931 cited above states that "Trains were rerouted on the Corpus Christi Terminal association tracks..." The Port's strategy was to maximize competition among the three major railroads serving Corpus Christi by allowing all of them to use Port-owned tracks as necessary. An agreement required each railroad to assume heavy switching duties for the Port tracks during a period of one year on a rotating basis. For the two years during which SP or TM had the responsibility, the companies elected to assign joint crews to perform the work, but how long this approach persisted is undetermined. The CCTA had its own yard office, clerks and trainmaster at the new interchange yard north of the Tule Lake Lift Bridge.

Above: This aerial photo

(c.1960, Carl Codney collection) shows the bascule bridge carrying a train beside the new Harbor Bridge.

The two bridges coexisted for thirteen months because of legal proceedings

attempting to prevent abandonment of SP's tracks over and near the bascule

bridge. The Harbor Bridge construction required removal of SP's yard and depot

downtown, yet, SP's rail line might otherwise have remained usable (perhaps

with track alterations) if not for

removal of the bascule bridge. In May, 1959, the railroads began negotiating

with employee unions regarding work rule changes necessary for use of the Tule

Lake Lift Bridge that was due to open in October. The Brotherhood of

Trainmen refused to accept a new agreement, and a year later in May, 1960, the railroads

gave thirty days' legal notice of their intent to impose new work rules. The

dispute was sent to mediation in June, but with no agreement by October, the railroads

petitioned the ICC for approval to begin using the new work rules and permission to abandon specific tracks

over and near the bascule bridge. The ICC granted the railroads' petition on

November 16, 1960, and the rails to the bascule bridge were cut two days later. The dispute continued, the

bascule bridge was dismantled, a strike

was threatened, Federal courts refused to intervene, and the railroads went

back to the ICC to request an order declaring the new work rules to be in

the "public interest" (so that a strike could be deemed illegal;

employees would then be on notice that a strike risked the reinstatement

protections of Federal law.) The

final ruling from the ICC did not occur until 1967!

Presumably well before then, some sort of agreement was reached because the Port

and the railroads serving it operated effectively through the 1960s.

It was no secret that the lengthy trestle across the bay to Portland could not be sustained indefinitely, but there was insufficient rail traffic to justify the expense of a rebuild. The Coast Guard viewed it as a safety hazard and had been hounding SP to make other arrangements for its main line into Corpus Christi. The Port's written history asserts the 1970s as the timeframe in which SP stopped using the trestle, but it was actually 1965. SP obtained rights on MP's tracks between Sinton, Odem and Corpus Christi on August 16, 1964. RCT records list SP as officially abandoning 6.08 miles between Corpus Christi and San Antonio in 1965; these were the tracks from North Beach across the trestle into downtown Portland. SP's last train to operate over the Rincon Channel trestle was April 15, 1965. SP began using the new rights on MP's tracks the next day.

Above: This notional railroad

map of Corpus Christi (from a sketch by Carl Codney; thanks, Carl!) shows the

tracks of the three major railroads that served the city. Historically, the

"interchange tracks" on Alameda and Staples streets near downtown owned by MP

and SP, respectively, were used for TM interchanges. By 1949, MP and TM had

built a joint line for new customers, but still handled their interchanges via

the Alameda Street tracks. The tracks on Alameda and Staples streets remained in

place into 1969 but then were taken up c.1970 as they could not survive the

construction of Interstate 37 into downtown. All of the T&NO tracks on the map

were owned by the Port and were used by the other railroads to a lesser extent.

TM used the Savage Lane line between the joint yard and the Port, and all three

railroads used the Tule Lake Lift Bridge and various tracks on the north side to

operate into the Port's new yard.

In 1997, the Port leased its tracks to the

Corpus Christi Terminal Railroad. In 2022, the lease changed to the Texas Coastal

Bend Railroad, a subsidiary of transportation services company Watco.

SP had to abandon its original SA&AP yard because the

property was needed for the south approach to the new Harbor Bridge. Since the

bascule bridge had to be removed to widen the ship channel, SP also had to

abandon the original SA&AP main track between North Beach and downtown (orange dashed line.) SP replaced its yard by teaming with TM to build a

new joint yard on TM's main line west of downtown along Agnes

Street. SP began operations there in November, 1960 once the ICC had ruled in

favor of the railroads regarding new work rules. Each railroad owned individual tracks, but the whole yard was used by

crews of both railroads. The railroads elected to use joint crews to perform yard switching

as it was more efficient, i.e. fewer crews operating simultaneously reduced yard

congestion, improving productivity. The use of joint crews was a major part of the

complaint filed by the Brotherhood of Trainmen who asserted that such crews cost the

union jobs by reducing the total number of employees needed to switch the yard.

The joint yard became connected to the Tule Lake

Lift Bridge when the Port opened the new Savage Lane tracks. Among

several alternatives, the route selected was

not the closest to Savage Lane, but the name

stuck. The tracks crossed MP's main line from Odem about 0.4 mile south

of the bridge. Tower 211, an automatic interlocker with a number assigned by RCT, was installed to manage the

crossing. The

location became known as MP Junction. The Port also had to build

a track to

connect the Tule Lake Lift Bridge to SP's existing line on North Beach leading to the

trestle to Portland, which would remain in use for five more years.

Like the Savage Lane line, this track was effectively part of SP's main line between

Corpus Christi and San Antonio, which undoubtedly factored into the Port's

decision to use SP

track standards for construction, as Carl Codney explains...

All of the new construction was built to SP standards with SP switch targets and SP mileposts markers. The right of way was owned by the Navigation District. Thus, the interlocker was built as a MP / T&NO crossing. A T&NO signal maintainer was responsible for the crossing interlocking and the lift bridge interlocking. A new interchange yard was built just north of the Tule Lake Lift bridge. This eliminated the need for street tracks downtown. The SP maintained the entire track from Savage Lane to the old SP main line on North Beach as their main track until the SP abandoned the trestle and re-routed trains via Sinton-Odem-MP Junction.

Competition and consolidation in the 1980s and 1990s greatly

affected railroad operations in Corpus Christi. In 1982, MP was acquired by

Union Pacific (UP) but was allowed to operate under the MP name. In 1996, UP merged

SP and soon thereafter, MP and SP became fully integrated into UP. Although historic aerial imagery shows

that at least by 1983, the Port had reached its current westward extent at the

Viola Turning Basin, nearly nine miles from the Harbor Bridge, the track

infrastructure did not exist that far west on the north side of the Port. A

lengthy track extension from the north side of the Tule Lake Lift

Bridge to UP's main line to Odem was built so that the Lift Bridge could be

removed due to structural issues. The Port infrastructure was improved with the

expansion to the west and the rail connection there to UP's main line was

superior to the route over the Lift Bridge.

The UP / SP merger created competition issues in Corpus Christi

because it merged the two largest railroads serving the city. The other major

system that had evolved in the western U.S. in the 1990s was Burlington Northern

Santa Fe (BNSF). Though it had no tracks south of Galveston, BNSF became

important with respect to the UP / SP merger as a means of supplying railroad

competition into the Corpus Christi market. Approval of the UP / SP merger by

the Surface Transportation Board (STB, effectively the successor to the ICC)

required agreements through which BNSF was granted rights to serve Corpus

Christi on UP's tracks. A year earlier, Kansas City Southern (KCS) had acquired

49% ownership in TM even though KCS' nearest tracks were at

Beaumont. This move

proved prescient when TM was also granted rights on some of UP's lines to

bolster competition in south Texas. KCS acquired controlling interest in TM in

2004, with STB approval granted in early 2005. Today, UP, KCS and BNSF all serve

Corpus Christi and the Port.

|

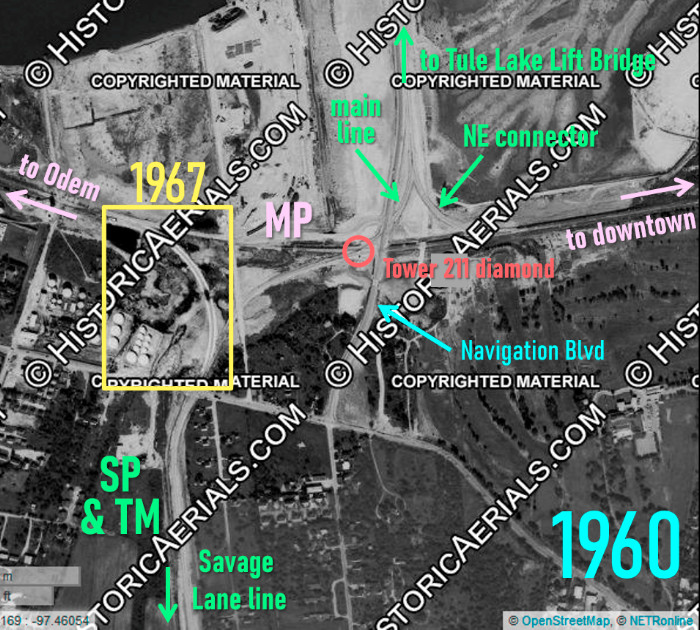

Left:

This annotated 1960 image ((c)historicaerials.com) has been overlaid

with a snippet from a 1967 aerial image (yellow rectangle) to show the

addition of the southwest quadrant connecting track at the Tower 211

crossing. When the crossing was originally built in 1959, neither SP nor

TM had trackage rights on MP's tracks to Odem. Since there was no

reason for MP trains from Odem to go south on the Port's Savage Lane line toward

the joint TM / SP yard, a southwest quadrant connector was not included

in the crossing topology. When SP began using MP tracks in 1965, a

major change in traffic flow occurred. SP's main line to San Antonio began

routing

between the joint yard and Sinton via Tower 211 and Odem, and the southwest

quadrant connector was needed to facilitate this routing. The MP tracks are generally east / west in this area, and from Tower 211, the Port tracks run north to the Tule Lake Lift Bridge and south toward the joint yard along the Savage Lane route. Yet, the Tower 211 diamond was not close to being a right-angle crossing. The displacement of the Savage Lane line approximately 1,500 ft. west of the Tule Lake bridge alignment resulted in the need for curves on both sides of the crossing and a 26.5-degree angle at the diamond. Thus, what looks like a northwest quadrant connector at first glance is actually the main line curving to intersect the diamond. On the two oblique angle sides of the diamond, short connecting tracks in the northwest and southeast quadrants were incorporated into the crossing layout. They are not annotated on the image as they are very short and sit mostly within the red circle. Note the tiny black dot visible on the south side of the tracks inside the red circle. This is the Tower 211 cabin casting a short shadow from a midday sun. Navigation Blvd. shared the Tule Lake Lift Bridge with the Port tracks and runs parallel to the Port on the north side toward North Beach. It originally curved around the west end of the Turning Basin to connect with city roads but had to be rerouted farther west as the Port expanded. The Lift Bridge was its final location. It continues south from the Port area nearly four miles. |

| Right:

When Google Street View began capturing street-level imagery in 2007,

the Tule Lake Lift Bridge was still operational, at least to a limited

extent. This image captured in

November, 2007 shows the bridge lifted for the passing of a ship. The

view looks north along Navigation Blvd a short distance north of the UP

grade crossing. Why did the Lift Bridge have to be

dismantled? Applied Science International, a company that assisted in

developing the demolition plan, explains... Cracks in the bridge’s shafts and sheaves, part of the pulley system, had forced the port to ban car traffic and allow only rail traffic since September 2006. Structural cracking along the bridge’s lifting system has doubled [since then], making it a hazard not only to port and railroad employees, but also to daily business. |

|

|

Left: A

connector track at the Tower 197 crossing in Robstown allows traffic

from Laredo to proceed north on UP's route to Houston, and southbound

traffic from Houston to go west on the TM to Laredo. This was built when

KCS acquired the TM; KCS has trackage rights on UP from Victoria south

to Robstown via Bloomington. (Google Earth

image) Below: This snippet from a 1922 Sanborn Fire Insurance map of Robstown shows connecting tracks in both of the south quadrants. The southeast connector facilitated service between Brownsville and Corpus Christi. The southwest connector most likely had been used for Brownsville - San Antonio traffic when the SLB&M first opened, avoiding the circuitous TM / SA&AP route through Corpus Christi and Gregory in favor of the TM / SA&AP route west via Alice. Both routes went through Skidmore but the west route would have been less congested.  |

|

Left: This Google Street View image in Robstown looks south along UP's main track to Harlingen. In the foreground, the TM crosses the Tower 197 diamonds. Just beyond the equipment cabinets near the center of the image, the connector for traffic to Laredo is visible as it begins to curve to the right toward its connection with the TM about 0.4 miles west. |

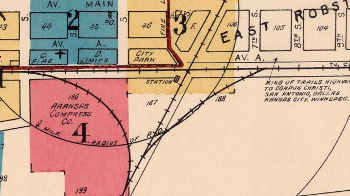

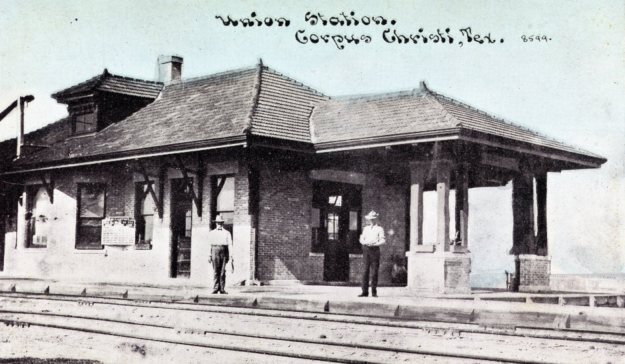

Above Left: 1955 view of SP's

SA&AP-heritage passenger depot downtown, removed for construction of the Harbor

Bridge (Corpus Christi Caller-Times photo)

Above Right: the TM Union Depot

(Carl Codney collection) Below Left: trackside view of MP's SAU&G-heritage passenger

depot in 1949 (H D Connor Collection)

Below Right: the SAU&G depot, still in use as offices by UP

(Sean Wray photo, 2015)

Special thanks to Carl Codney for his substantial contributions to this page.