Texas Railroad History - Tower 91 - West Point

A Crossing of the Missouri, Kansas & Texas Railway and the

San Antonio & Aransas Pass Railway

|

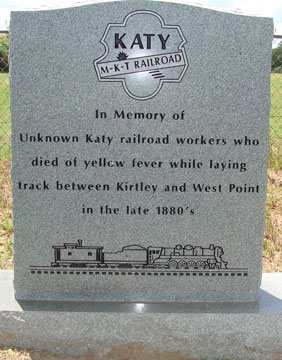

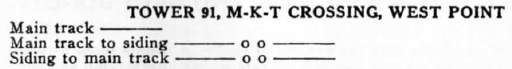

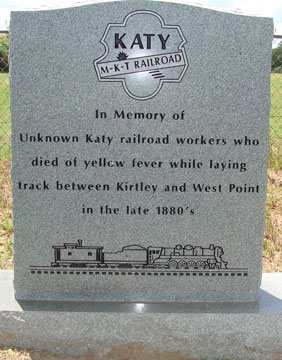

Left:

This marker stands in the Woods Prairie Cemetery near West Point memorializing

the Katy railroad workers who died of yellow fever in 1887 during construction

of the Missouri, Kansas & Texas (MK&T, "Katy") rail line between Taylor and La

Grange. This uncredited photo comes from an article in Footprints of

Fayette County by two railroad engineers, Larry Lutringer and

W. O. Wood, who write that the marker was...

...placed

there by Bobbie Robbins Stevens in 2013 and paid for by her mother, Susan Grace

Young Robbins. Susan had heard the story of the railroad workers all her life

and had helped her Aunt Molly (Mrs. Charles Young) tend the graves when she was

a child. It was Charles Young and his brother Zed (Bobbie Robbins Stevens'

grandfather) who gave the railroad foreman permission to bury the men in the

cemetery. The railroad workers who died earlier were buried in a field next to

the railroad tracks near Primm, which was later renamed Kirtley.

The yellow fever epidemic that killed the Katy railroad workers was small in

comparison to the one in nearby La Grange twenty years

earlier which

killed at least 20% of the town's population. The fatality rate was 90% for

those infected. The

New Orleans Crescent of September 26, 1867

carried a story describing the devastation one journalist saw in La

Grange...

"Those remaining of the citizens number barely 500 yet the interments have

reached as high as 24 in two days. ... Every house in the town is filled with

sickness and with death. Business has ceased entirely; the newspapers are no

longer published; the jail has been emptied of its inmates, who fled in terror

from the scene of desolation. In some cases there is no one to bury the

dead. Whole families have been swept away. ... The stores are all closed, and to

crown the misery of the unfortunate inhabitants, starvation is staring them in

the face. ...there were no provisions to be had in the town — not

even corn meal to make gruel with." |

According to Fayette County sources, West Point was

founded by William Young in 1840 and named after his hometown, West Point,

Mississippi. This was long before two railroads came through the area in 1887,

the first being the Taylor, Bastrop & Houston (TB&H) Railway. West Point's

location roughly midway between Smithville and La Grange placed it in the middle

of a TB&H track segment that was part of 79 miles

built between Taylor and La Grange that year. The tracks actually terminated eleven miles beyond

La Grange at Boggy Tank, a made-up name for the middle of nowhere. Why did construction stop? As was often the case for Texas railroads

in the post Civil War era, financial and legal issues halted the work.

The TB&H had come into existence because of Jay Gould, a notorious east coast rail baron,

who had begun to

expand his empire into Texas in 1879 through the Missouri Pacific (MP) Railroad

which he controlled. Gould was also President of the Missouri, Kansas & Texas (MK&T, "Katy") Railway

which had a multistate route network including tracks across the Red River into

Denison. The Katy was leased to MP,

and publicly, Gould made sure the new Katy construction he planned was reported in the press as MP activity. Track ownership, however,

would be titled to the Katy because MP was a

"foreign" railroad; it could not comply with Texas law requiring railroads in

Texas to be headquartered in state. It could, however, operate in Texas using a

Texas-based subsidiary or lease; the Katy lease served this purpose for Gould.

Ironically, the Katy was also a "foreign" railroad -- it had no Texas

railroad charter -- but it had been allowed by the Legislature to enter Texas in the early 1870s

under its Kansas charter for the purpose of bridging the Red River to connect

with the Houston & Texas Central (H&TC) Railway at Denison.

Gould figured that was enough to make it a "Texas railroad"; courts would later

disagree, but no one challenged Gould as he built new MP tracks in Texas under

Katy ownership. [Everyone wanted more railroads!] Gould's control of the Katy,

however, was tenuous -- he owned very little Katy stock and he had been elected

its President

by allies who had infiltrated its Board of

Directors over several years. The lease enabled Gould to transfer Katy profits to MP where he had

more substantial ownership. Accounting-wise, the Katy broke even at best, to

the detriment of its stockholders. Gould's plan was to lay tracks for MP under

Katy ownership from

Fort Worth to Houston by going south through

Waco and Temple before

eventually turning east through Smithville and LaGrange. By the end of 1882, MP

(Katy) tracks had reached Taylor, between Temple and Smithville.

The end of track remained at Taylor for a time due to the

political climate in the Texas Legislature. In 1882, it had repealed the land

grant law and lowered authorized passenger fares, and there were additional railroad

regulations under consideration. By 1886, Gould was ready to proceed

and he directed MP to resume construction south out of Taylor. It did so by

soliciting a state charter for the Bastrop & Taylor Railway headed

up by associates of Gould. Work commenced in

1887 under a revised name, the Taylor, Bastrop & Houston (TB&H) Railway. After passing

through Bastrop and crossing the Colorado River, the route took a southeast

heading into Smithville. From there, it went east through West Point and continued toward Houston via La Grange (where it would cross the Colorado River a second

time.) Once again, the TB&H activity was publicly deemed to be MP's effort, but

upon completion, the Katy would acquire the TB&H and own

the route for MP's benefit. At least... that was the plan.

By late 1887, financial issues

had begun to mount for Gould as one of his Midwest railroads went bankrupt.

Meanwhile, legal issues in Texas began in December when another Gould railroad,

the International & Great Northern, was sued by the Texas Attorney General

for failing to live up to its charter, exhibiting poor service and crumbling

infrastructure. Work on the TB&H stopped immediately, eleven miles

east of La Grange; the site was christened Boggy Tank.

By 1889, Gould's control of the Katy had collapsed; Katy stockholders summoned a quorum and fired

him in May, 1888, and Texas courts broke the lease to MP, finding it unlawful. In

October, 1891, the Legislature passed a railroad charter bill to allow a new

Texas-based subsidiary of the Katy to build and operate tracks in Texas while

legalizing what the Katy had built under the MP lease. Construction eastward from Boggy Tank

resumed and the Katy reached Houston in 1893. In 1915, the Katy went into

bankruptcy and was operated by a court-appointed Receiver. In April, 1923, the

bankruptcy ended and the company was re-constituted as the Missouri - Kansas - Texas Railway,

but

everyone still called it the Katy.

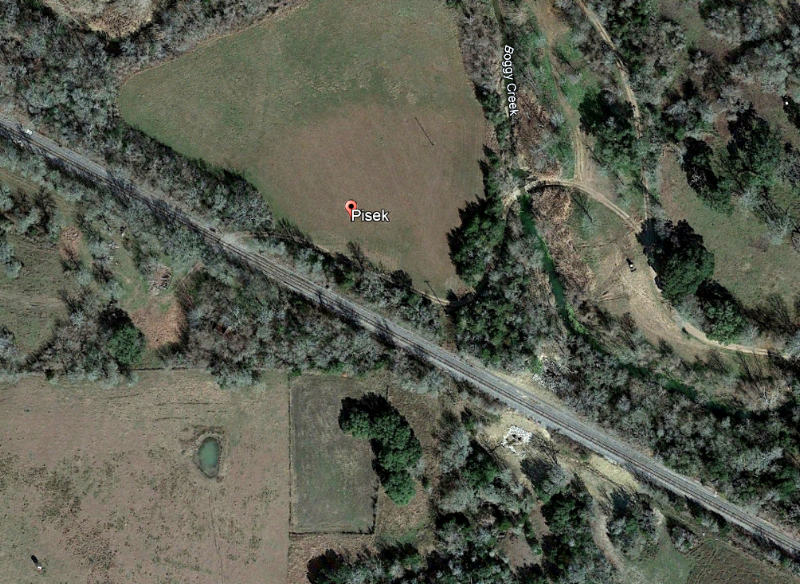

Where Was Boggy Tank? 29 55 N, 96 35 W

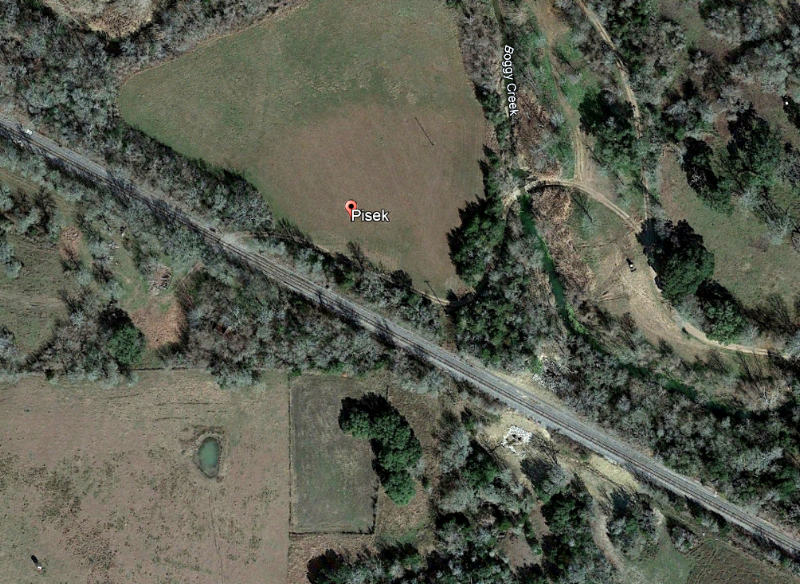

Right:

Referring to Boggy Creek, the Handbook of

Texas says...

"Boggy Tank was a swampy area that gave

the creek its current name. The railroad built a turntable there

to reverse trains for the run back up the track. The town of Pisek ...

moved one mile to the tracks. The railroad called the site Sandy Point,

but the name Pisek stuck. By 1896 the community became a shipping center

and had a post office and saloon..."

The Post Office closed in 1907. Since the turntable has been gone

for more than a century, it is not surprising that no visual evidence of

it is found on current satellite imagery.

Nearby, however, is something

curious ...(above)

which appeared on both sides of the tracks in recent years. (Google Earth, January, 2022) |

|

|

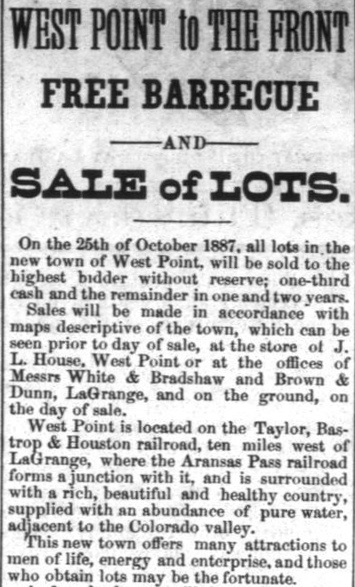

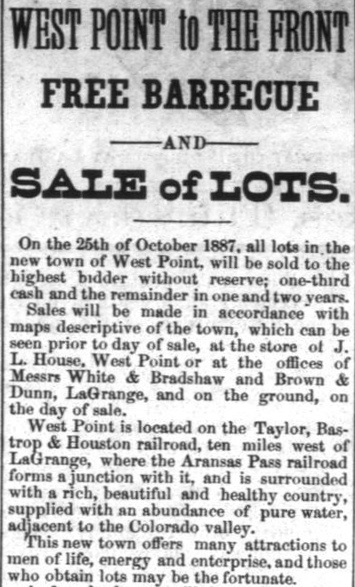

Left:

The La Grange Journal

of October 6, 1887

carried this advertisement (listed in its "New Ads" column) announcing

that all lots in West Point would be sold on October 25th to the highest bidder.

And who among Texans can resist free barbecue?

Although West Point had existed as a community since 1840, it was merely a rural

outpost with a handful of families at best. The arrival of the railroads in 1887

brought big changes. According to the La Grange

Journal, TB&H trains began operating through West Point in October.

The San Antonio & Aransas Pass (SA&AP) Railway was building

north

toward Waco on a surveyed route that would also pass

through West Point. Its trains were anticipated to reach town by

November 25th, but the precise date of the first train into

West Point for neither railroad has been determined.

The arrival of two railroads into West Point in the span of a month or two spurred

local real

estate promoters into action. The ad uses the present tense to assert that the "...Aransas Pass forms a

junction..." with the TB&H. This may imply that SA&AP work trains

had reached West Point by early October, but even if the rails were

still on the outskirts of town, it was rather amazing progress. The

SA&AP had completed its

original main line between San Antonio and

Corpus Christi only a year earlier before promptly

embarking on a massive construction program in 1887. One of the new

tracks

branched off the SA&AP main line at Kenedy and had been completed as far as Wallis, heading for Houston. A branch

from the Wallis line at

Yoakum was the one that went north through West Point, eventually to

reach Waco.

The SA&AP's northward construction

stopped at West Point while a bridge over the Colorado River north of town was

contemplated. The bridge opened in 1889 and the line was extended north

to Lexington that year. A track segment from Waco south to Lott was also

completed in 1889. The SA&AP's receivership commenced in the summer of 1890,

but the final 58-mile segment between Lexington and Lott was completed

in 1891 during the bankruptcy. |

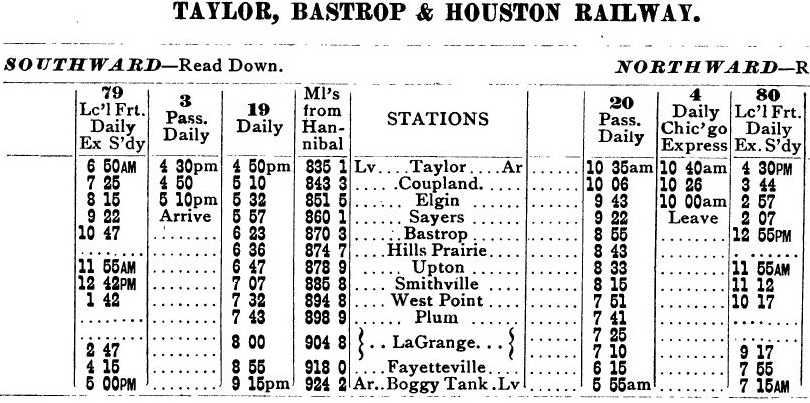

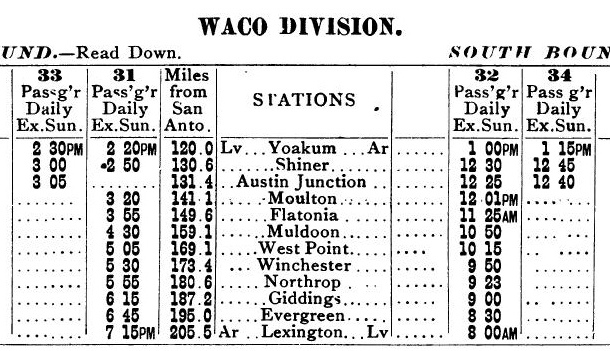

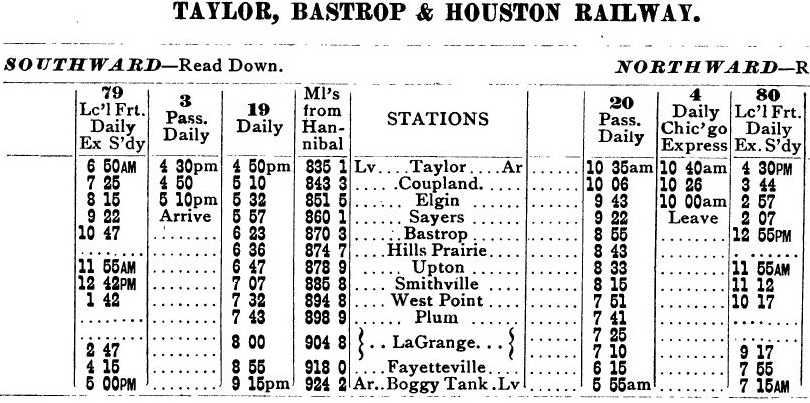

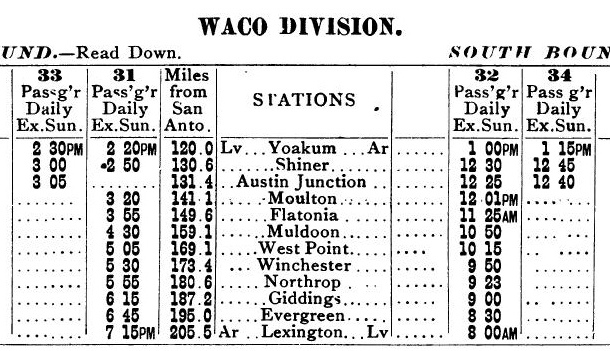

Above:

A marketing pamplet,

The Texas Spring Palace, was published in 1890 to proclaim the virtues of Texas living,

and it included a set of railroad timetables

for the entire state. These two showed the scheduled passenger service

through West Point for the TB&H (left) and

the SA&AP (right).

As of 1890, the TB&H terminated at Boggy Tank and the SA&AP terminated at Lexington. Note that the TB&H table includes a

"Miles from Hannibal" column. Hannibal was an important Missouri junction in Gould's MP

network.

For safety purposes, the Railroad Commission of Texas

(RCT) began regulating crossings of two or more railroads, both "at grade" and

"grade-separated", under new authority granted by the Texas Legislature in 1901.

Grade-separated crossings presented few safety issues, but RCT had the authority

to resolve disputes between railroads over whether a crossing should be at grade

or grade-separated (as it did in one

notable case in El Paso.) Under its new authority, RCT

released an order dated November 8, 1901 that mandated the installation of swing

gates at all railroad diamonds, pending further orders to install interlocking

plants. The presence of a gate did not affect the state law that required all

trains to stop at a non-interlocked diamond before proceeding. Thus, gates

accomplished little beyond displaying a STOP sign (in the middle of the gate)

positioned against one track.

Eventually, trains were authorized to approach gated crossings at restricted

speed, slow enough to come to a complete stop if the gate was closed but

otherwise permitted to continue across the diamond.

The Katy /

SA&AP crossing at West Point was likely gated relatively soon after RCT's

1901 order was issued. It was not, however, prioritized for an

interlocker. RCT wanted to "spread out" the timing of interlocking tower

projects so its limited engineering staff could take the time to review and

approve each plan prior to construction. The staff also had to inspect and

approve each installation prior to authorizing it to become operational. Under

its own priority determinations, RCT issued orders for railroads to interlock

specific crossings, but railroads could also solicit RCT's permission to begin

designing an interlocking system for any particular location. No evidence has

been found to indicate that the railroads requested RCT permission for an

interlocker at West Point, nor was there a good reason

why West Point should be prioritized. The crossing was near the town's depots,

hence most trains were stopping anyway. Moving slowly in or out of a depot meant

that an additional brief stop at the crossing created relatively little penalty,

i.e. there was no significant delay and only a limited loss of momentum.

Preserving momentum was a key benefit of interlockers. Slowing a train from

track speed down to zero and then reaccelerating to track speed cost significant

fuel and water for steam locomotives, and added delays. At interlocked

crossings, this was an avoidable penalty in the vast majority of cases since the

diamond was usually unoccupied.

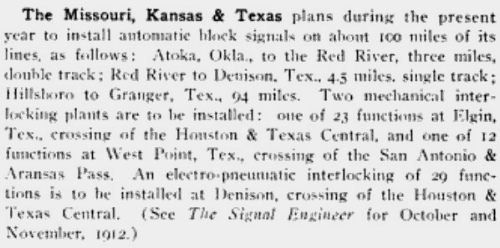

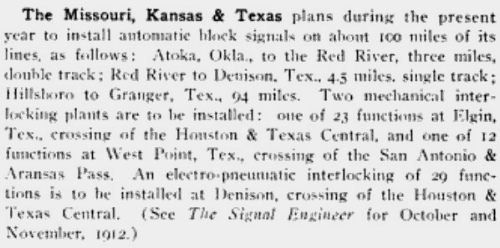

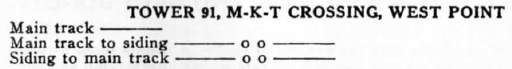

Right:

The January, 1913 issue of The Signal Engineer

identified West Point as a location for a planned interlocker

installation by the Katy. No order from RCT mandating a West Point

interlocker has been found, so this may have resulted from a request to

RCT by the railroads based on current

traffic levels. The plan was executed and RCT's published table of active

interlockers dated October 31, 1913 showed that Tower 91 at West Point

had been commissioned for operation twelve days earlier.

As the article projected, Tower 91 had a 12-function mechanical

plant, a basic design for a crossing of two railroads consisting of a

home signal, distant signal and derail in each of the four directions.

It was undoubtedly a two-story tower, but no photos have been found.

The article attributed the plan to the Katy, so it is unsurprising that

RCT records show the tower staffed and maintained by Katy personnel.

Under RCT's rules, the capital outlay for the tower and its interlocking

system would have been shared equally by the two railroads because the

crossing existed prior to the 1901 law. Recurring staffing, utilities

and maintenance expenses would have been split evenly between the two

railroads because they each used

half of the interlocker functions. |

|

|

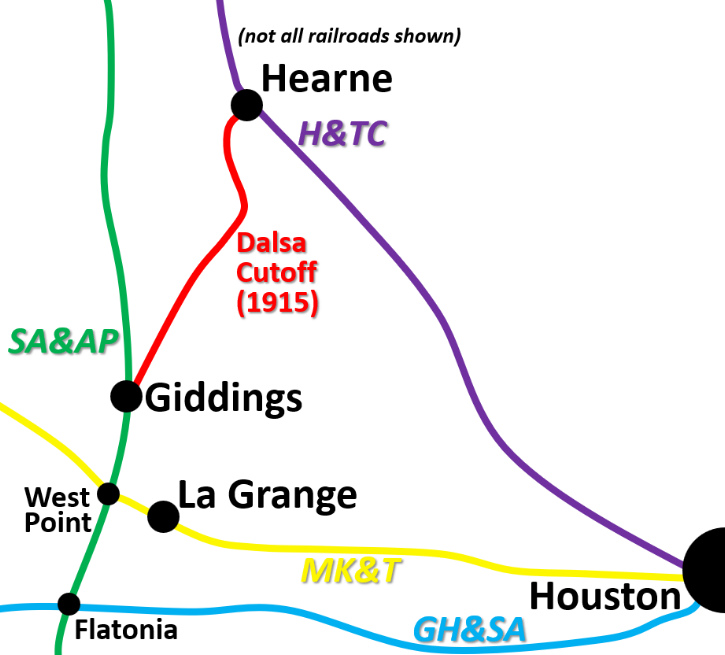

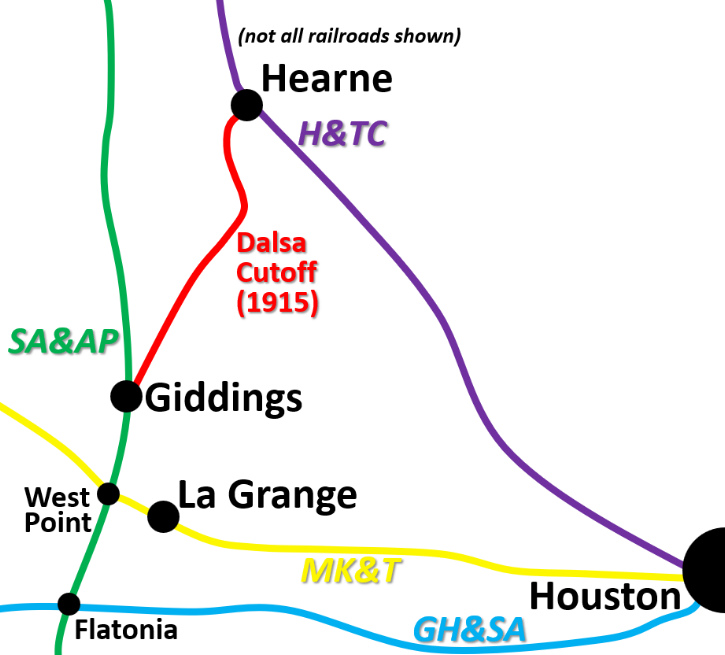

Left:

area map (not all railroads shown)

The installation of the interlocker at West Point seems to have been well-timed. Traffic

across the diamond increased substantially a little over a year later when

Southern

Pacific (SP) opened the Dalsa Cutoff between Giddings and

Hearne. SP owned the H&TC which went north to

Dallas and Denison, and it owned the Galveston, Harrisburg & San Antonio (GH&SA) Railway

which went west to San Antonio,

El Paso and the west coast. SP

traffic between points west on the GH&SA and points north on the H&TC had to

pass through Houston, incurring

significant delays due to track congestion. In 1915, SP opened the Dalsa Cutoff

and negotiated

trackage rights on the SA&AP

between Giddings and Flatonia. SP trains

from the west could turn north at Flatonia and take the Cutoff

at Giddings to proceed to Dallas via Hearne. The new

route was shorter and faster between Dallas and San Antonio (hence, the "Dal-SA"

name) because it bypassed Houston. Work on the Cutoff commenced in 1914

and it opened in March, 1915. Whether a

new tower at West Point had been part of SP's original plan for the

Cutoff has not been determined.

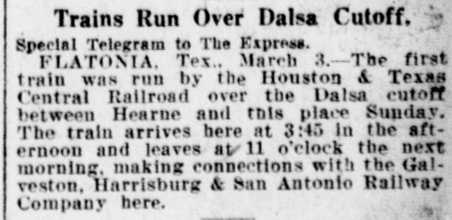

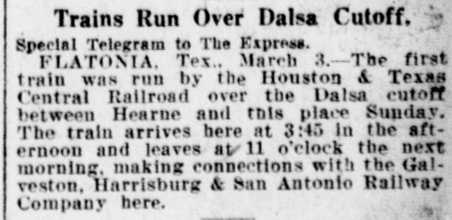

Below:

The San Antonio Express of Thursday, March 4,

1915 carried this news item reporting that the first train to operate over the Dalsa

Cutoff had run the prior Sunday, which was February 28, 1915.

|

SP's close association with the SA&AP dated back to

1892. To help the SA&AP exit receivership, SP had offered to back SA&AP construction

bonds for any new lines it built. SP was prevented from buying the SA&AP by

state railroad competition laws, but it wanted the railroad to be successful

because its south Texas track network was complementary to SP's and there was

anticipation of significant interchange traffic. The bankruptcy court

approved the offer, and it worked well for both railroads until RCT began an

investigation in the spring of 1903. RCT believed that SP illegally held a

controlling interest in SA&AP stock, and they were able to prove it. SP

admitted malfeasance and RCT imposed a penalty that ordered cancelation of all

SA&AP stock held by SP, a loss of roughly four million dollars. More

than two decades later, SP was finally able to buy the SA&AP in 1925 by seeking

approval from the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC.) Authority granted to ICC

in the Transportation Act of 1920 preempted RCT's authority in railroad mergers and acquisitions,

regardless of Texas law. In 1934, SP

consolidated most of its Texas and Louisiana railroads, including the SA&AP,

into a single operating entity, the Texas & New Orleans (T&NO) Railroad. At that

point, the SA&AP corporation ceased to exist and ownership of its lines was transferred

to the T&NO.

|

Left: A 1940

T&NO employee timetable shows Tower 91 with "Continuous" staffing.

It has these whistle codes for trains to signal the tower

operator to line signals and switches for specific movements. RCT's

final comprehensive interlocker report published at the end of 1930

listed Tower 91 with twenty functions. The increase from the

original dozen was associated with signals, derails and switches

for sidings and connecting tracks. |

Above Left: With

North to the right, this West Point track chart dated

December 12, 1924 (Stuart Schroeder collection) shows connecting tracks in both of the eastern quadrants of

the diamond. The rectangle immediately northeast of the diamond is labeled "Intlr.

Tower" (presumably "Interlocker Tower".)

Above Right: This photo (Jim

King, c.1999) facing east along the former Katy tracks shows the equipment cabin

that housed the automatic interlocking plant at West Point after the Tower 91

manned structure was retired. The cabin is sitting trackside in the northeast

quadrant of the crossing where the tower once stood. The date of the tower's

retirement is undetermined. By 1959 (per a T&NO employee timetable)

the

crossing had been converted to an automatic interlocking.

Above: This undated photo

(Chino Chapa collection) shows a passenger train at the Katy depot in West Point. The view is

to the west and the train is headed for Smithville. Bruce Blalock notes that

"...there are teams and buggies but no automobiles, so I'm thinking this would

be around 1900." A smaller Katy depot that presumably replaced this one is

reported to have been relocated to the Smithville Railroad Park, refurbished and

relabeled as Smithville's Katy depot.

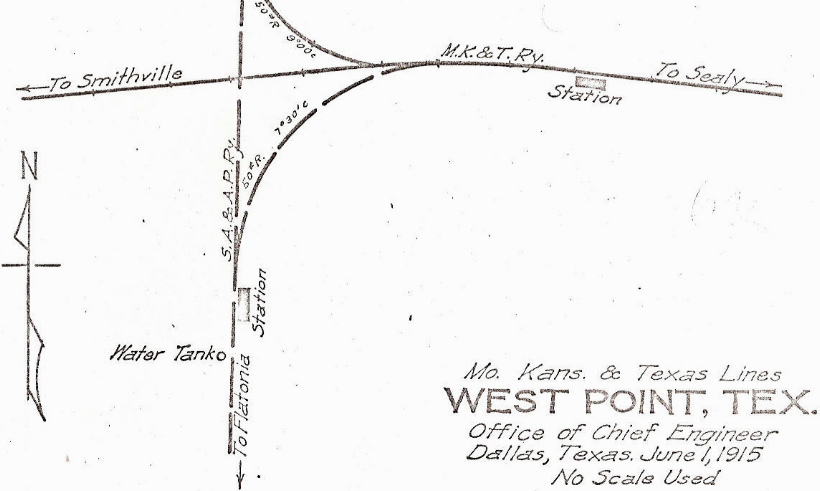

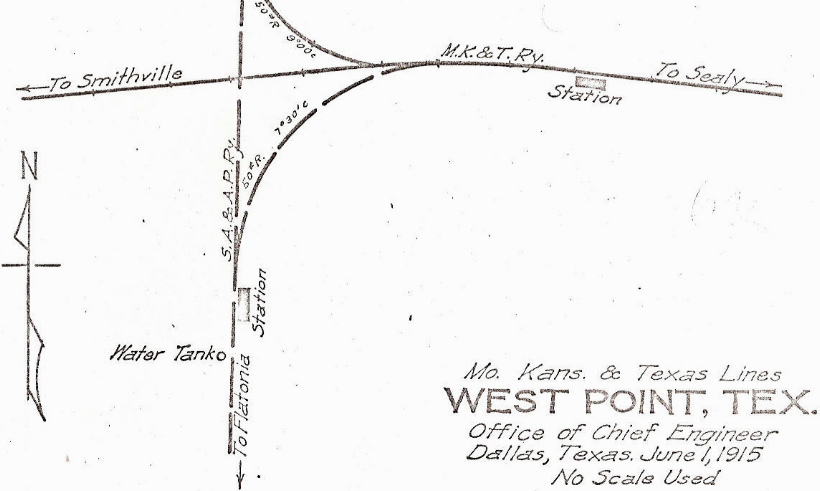

Right: This 1915 track chart (Ed

Chambers collection) shows the relative locations of the two stations at West

Point, and indicates that the connecting tracks present in the 1924

track chart were already in place by 1915.

Below: undated photo of the Katy depot (William Wessels collection)

During World War I when railroads were governed by the U. S.

Railroad Administration (USRA), the two railroads at West Point applied

to RCT for permission to build a joint station, noting that the USRA

district director concurred with their request. RCT granted the

application, but no evidence has surfaced to indicate that a Union

Station at West Point was actually built. |

|

Union Pacific (UP) acquired MP in 1982, but MP

continued to operate under its own name. UP then acquired the Katy in 1988 and

merged it into MP, reuniting the railroads a century after MP's lease of the

Katy had been broken by Texas courts. In 1996, UP acquired and merged SP, and the

following year, MP became fully merged into UP. As a result, both

tracks at West Point are now owned and operated by UP. The former Katy

line remains active in both directions, although it no longer continues all the

way to Houston, terminating 22 miles east of Sealy in the town of Katy. The Dalsa Cutoff

remains very active through West Point, but the former SA&AP tracks north of Giddings

(to Cameron and Waco) were mostly abandoned in 1959

except for a lengthy track segment north from Cameron that became an industrial spur.

South of West Point, the former SA&AP tracks remain operational through

Flatonia all the way to the

original branch point at Yoakum.

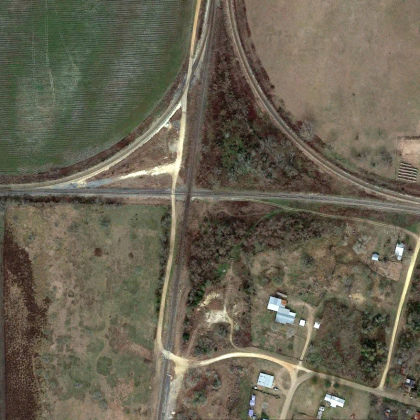

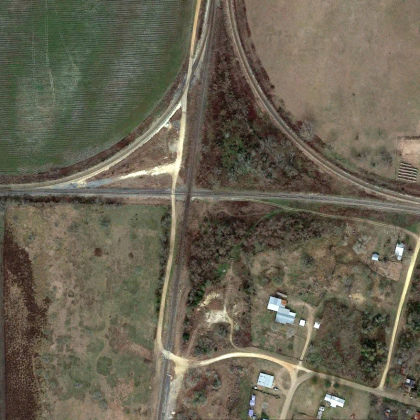

Above: The

presence of connecting tracks at West Point has changed considerably in recent

years, no doubt a manifestation of UP's ownership of both main lines. These Google Earth

satellite images (left to right,

2001, 2018 and 2022) show the gradual addition of connectors in three of the

four quadrants. The 2001 image shows that by then, the previous connecting

tracks depicted on the early track charts had been removed long enough to give

very little evidence that they had ever existed. Historic aerial imagery

suggests that those tracks had been removed by 1974 and likely earlier.

New connectors in the two north quadrants were in place by 2018, and a connector

in the southeast quadrant was added between 2018 and 2022.

Below Left: These Google Street View

images from May, 2011 show rail cars on the northeast quadrant connector, which

obviously dated back to at least that year. The

sign on the equipment cabin identifies the connector as "LCRA Jct", suggesting that

the movement of coal trains to and from the Lower

Colorado River Authority (LCRA) coal-fired power plant seven miles east

of La Grange was the impetus for building it. Below Right: In

this closer view of the railcars, the West Point crossing diamond is barely

visible in the distance.