Texas Railroad History - Tower

132 - McNeil

A Crossing of the International - Great Northern Railroad

and the Houston & Texas Central Railway

|

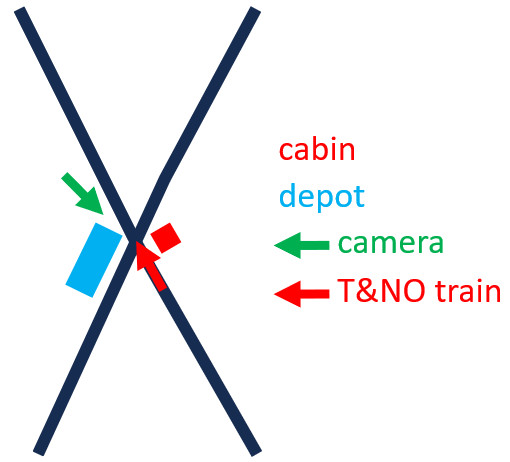

Left:

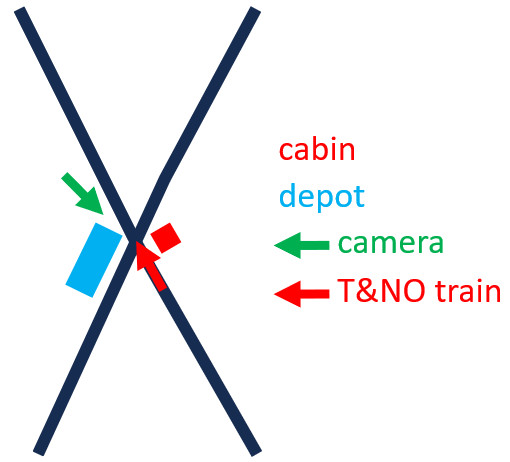

The two rail lines at McNeil crossed in an X-pattern, but with

slightly acute angles

north and south. The Tower 132 cabin sat in

the eastern quadrant of the diamond, and viewed from this angle, a utility

pole blocks most of the white "132" placard facing the camera. An identical placard is barely visible

beneath the roof overhang on the west (~ southwest) wall facing the tracks.

The

photo's timeframe is the mid 1960s and the

view is south-southeast along Southern Pacific (SP) tracks that date back to

the Austin & North Western Rail Road in 1881-82. In

the distance, Alco locomotive SP #6607 approaches the tower,

heading northwest with plans to proceed across the diamond and continue

to its final destination, perhaps the end of track at Llano. The rails

that SP #6607 will cross belong to Missouri Pacific, but the line was

originally built by the International & Great Northern (I&GN) Railroad in the latter half of 1876.

The mechanical interlocker at Tower 132 began operating in 1928. It was a

"cabin interlocker", typically a small, walk-in hut (often

called a "shanty" by railroaders) that housed the interlocking plant and

its manual controls. This cabin is presumably the original building, but

this is unconfirmed.

Note the exchange track behind

the cabin which doubles as a straight siding using the short connector

opposite the bicyclist.

(photos from the collection of Roger Shull, Crew Chief, Austin & Texas Central Railroad; thanks,

Roger!) |

The International & Great Northern (I&GN) Railroad

was created in 1873 by a

merger of the International Railroad and the Houston & Great Northern Railroad.

Although the companies merged, the railroad they were creating was delayed in

getting approved by the Texas Legislature because of the International's dispute

with the State over subsidy bonds that the Texas Comptroller refused to sign. A

compromise was finally reached in 1875, and a year later, the I&GN built

sixty-one miles of track from

Rockdale to Austin,

passing through this area (not yet known as McNeil) in late summer or early

fall. The track segment was part of a larger plan to build from Longview to the Mexican

border at Laredo (hence, the International part of the name.) From Longview, there was a favorable connection on the Texas &

Pacific Railway to Texarkana, where another

favorable connection led onward to St. Louis.

The I&GN was acquired by

rail baron Jay Gould in 1880, but he lost control later that decade. He

reacquired the I&GN in 1891, and his son George ran it for the next 25 years.

During this time, it went into receivership in 1908 and again in 1914. The 1914

receivership lasted until 1922, and the reorganized railroad company took a new

name, dropping the and to become simply the International - Great Northern (I-GN). The I-GN was a large railroad

with 1,100 miles of track in Texas, but its recurring financial issues made it a

candidate for takeover by a larger railroad system. The St. Louis - San

Francisco ("Frisco") Railway, fresh out of its own receivership, tried to buy

the I-GN in 1922, but the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) voted to reject

the sale. Missouri Pacific (MP) tried to buy the I-GN in 1924 as a means of

gaining access to the Texas market, but again, the ICC nixed the sale.

MP,

however,

had a fallback strategy that involved the New Orleans, Texas & Mexico (NOT&M)

Railway. It had been incorporated in 1916 to be the "holding railroad" for three

primary Gulf Coast railroads and several smaller ones that collectively operated

as the Gulf Coast Lines (GCL). The GCL concept had been the brainchild of Frisco

Chairman B. F. Yoakum, a native Texan with a long history in Texas railroading.

Yoakum had formed a syndicate with financial backing by the St. Louis Trust Co

to piece together a competitor to SP for Gulf Coast traffic, calling it the GCL.

It was not a railroad corporation (more like a marketing brand), but that fact

was inevitably lost on the general public; the GCL was

just another railroad component of the Frisco. The individual GCL railroads were managed

collectively by Frisco executives and were profitable. Their financial structure went through the St. Louis Trust Co.,

not the Frisco, hence the individual GCL railroads were not

directly involved in the Frisco's 1914 receivership. The St. Louis Trust Co.

effectively owned them, so they chartered a new NOT&M

to establish a top layer of executive management and placed all of the GCL railroads under it. The

NOT&M had been one of the GCL railroads, but in 1916, the new

NOT&M became, in essence, "the GCL" as a corporation, owning the

previous NOT&M and all of the other GCL railroads.

Rebuffed by the ICC, MP convinced the NOT&M to buy the

I-GN, simply to keep it out of the hands of competitors. This time, the

ICC approved the sale in June, 1924. MP followed up by proposing to buy the

entire NOT&M, i.e. the I-GN and all of the GCL railroads. The ICC approved MP's plan in

late 1924 and MP's purchase of the NOT&M was executed on January 1, 1925.

The I-GN continued to operate under that name until 1956 when it was

operationally consolidated (as were the GCL railroads) into MP. MP was acquired

by Union Pacific (UP) in 1982, and became fully integrated into UP operations in

1997.

|

Left: This 1876 map of Texas railroads (from the

Texas General Land Office) anticipated two lengthy rail lines running

northwest into the Texas Panhandle. The lines were projected by the

Houston & Texas Central (H&TC) Railway, which had already completed a

main line from Houston to Denison (1873) with branch lines to Austin

(1871) and Waco (1872). The line northwest out of Austin (blue circle)

was expected to reach Oldham County on the New Mexico border. The line

out of Waco (red circle) would head for the Canadian River in Potter

County, near where Amarillo

would be founded a

decade after the map was drawn.

H&TC's investors expected

both branches eventually to connect to the Atlantic & Pacific (A&P) Railroad, a

company chartered by Congress to build a transcontinental route from

Springfield, Missouri to the Pacific Ocean, generally along the 35th

parallel. Eastern and western portions of the A&P were built, but they

were never connected. Its

western tracks became part of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway while its

eastern tracks became part of the Frisco.

The branch line out of Waco (built by a related but separately chartered

railroad, the Texas Central) eventually reached Albany and stopped,

never building into the Panhandle. The H&TC did not proceed with

construction northwest out of Austin, but an unrelated railroad did. In

1882, the Austin & North Western Rail Road Co. completed sixty miles of

narrow gauge track to Burnet, but went no further. The plan was to build

to a connection with the Texas & Pacific at Abilene, but in 1883, the

railroad entered receivership. It was financially reorganized as the

Austin & Northwestern (A&NW) in 1888. It derived good business from granite quarries in the vicinity of Burnet and it carried all of

the granite used to build the state capitol in Austin. Tracks beyond

the quarries to Marble Falls were laid in 1889. The H&TC, under SP

control, bought the A&NW in 1891 and converted it to standard gauge. The

tracks were extended to Llano in 1892, but never went farther west. The

A&NW had crossed the I&GN at an unnamed rural location northwest of

Austin. The settlement that arose nearby became known as McNeil, named

for George McNeil, an A&NW section foreman. The A&NW continued operating

under its own name until it was fully merged into the H&TC in 1901. |

That year, 1901, was a significant one for Texas

railroads. A new state law commanded the Railroad Commission of Texas (RCT) to

begin regulating railroad crossing safety. State law already required all trains

to come to a complete stop before crossing another railroad's tracks at grade.

In addition to creating delay, the loss of physical momentum caused by the stop

increased the locomotive's fuel and water requirements as it accelerated beyond

the crossing. This was recognized as wasteful of time and fuel since the vast

majority of the time, a train approaching a crossing would find it unoccupied. The

new law was

focused primarily on the implementation of safety systems at crossings of two

(or more) railroads at grade that could eliminate the need for trains to stop,

saving time and fuel. [The law also included authority to regulate

grade-separated crossings, but early on, RCT concluded there was simply no

need.]

RCT began with a blanket order requiring swing gates to be installed immediately at all

crossings. This was somewhat odd; gates per se didn't qualify as the

kind of safety system that would permit a train to cross a diamond without

stopping. Thus, trains approaching a gate that was not positioned

against them still had to stop at the crossing

(whether they always did so is another question.) Much later, regulations were

enacted to allow trains to approach gated crossings at restricted speed, slow

enough to be able to stop comfortably short of the diamond if the gate was

"closed" against them but otherwise allowed to cross the diamond without

stopping if the gate was "open".

The state of the art in railroad grade crossing safety was based upon the

use of interlocker technology that had been developed and deployed in other

parts of the U.S. Such interlockers used a combination of home signals, distant

signals and derails to control how trains approached and crossed a diamond. RCT

began issuing orders periodically to require

railroads to adopt interlocker technology at specific crossings within a defined timeframe. RCT's

order dated June 18, 1903 required the I&GN and the H&TC to interlock the

crossing at McNeil by the middle of 1904, but that did not happen. The railroads

wanted to prioritize their capital investment to maximize the benefit of

interlocker installations by focusing on the busiest crossing locations, so it

is likely that they convinced RCT to rescind the requirement for an interlocker

at McNeil. Interlocking plants had to be operated by railroad employees, and at

crossings such as McNeil, the relatively limited amount of traffic over the

diamond could not justify the capital, labor and materials expense of

installing, operating and maintaining an interlocker. Sometimes, interlockers

were unnecessary because all trains stopped anyway at a nearby depot, close

enough to substitute for the required crossing stop. How the McNeil crossing was

handled in the early days has not been determined, but it is likely that a gate

was installed.

It was

not until 1928 that an interlocking plant was installed at McNeil. By this time,

H&TC had been leased (1927) to another SP subsidiary, the Texas & New Orleans

(T&NO) Railroad. RCT records

show that Tower 132 was commissioned there on July 13, 1928 with an 11-function

"mechanical cabin" interlocker, operated by H&TC. As 1928 was more than 25 years

after the first interlockers were installed in Texas in 1902, the technology had

evolved to address situations like McNeil where a busy line -- the I&GN --

crossed a line with limited traffic -- the H&TC. The expense of operating a

manned tower, particularly the labor costs, could not be justified at such

crossings. The tower operators would have very little work to do since the

signals would be set to allow virtually every approaching train on the busy line

to proceed across without stopping. Only rarely, when a train on the lightly

used track needed to cross, would the signals be set to warn an approaching

train on the busy line to prepare to stop. This condition would persist only

long enough for the crossing to complete, after which the signals would be

reset to allow continuous movements on the busy line.

Instead of paying a

team of tower operators to do very little actual work (potentially on a 24/7/365

basis), RCT approved the use of cabin interlockers. The cabin was typically a

small walk-in hut

that would house the interlocking plant and its manual

controls. Trains on the lightly used track would

always stop at the crossing. A member of the train crew would disembark

his train, enter the cabin and set the signals to allow his train to cross while

warning trains (if any approached) on the busy line that they would need to stop. When his train had

finished crossing, the crewmember would reset the signals to permit

uninterrupted crossings by trains on the busy line. He would then re-board his train

to continue its journey. Thus, cabin interlockers were actually operated by

train service employees of the less busy railroad.

Right: This excerpt

from a labor union's submittal to the National Railroad Adjustment Board

explains that there was an "employee covered by the agreement" that

operated the McNeil interlocker. The agreement specified this position

as an "agent-telegrapher-leverman" employed by MP (I-GN) to operate the

McNeil tower as a "joint agency" serving both railroads. The Union

disputed whether T&NO train crews could operate the interlocker on

Saturdays when, due to the new "40-hour work week", the tower was not

staffed. The response from I-GN (below)

states that train crews had always operated the interlocker when the

tower was not staffed.

|

|

The above labor dispute (in which NRAB ruled in favor

of the Union in 1953) provides some valuable insight into the operations at Tower 132.

The Union's submittal explains that as of September 1, 1949, T&NO operated only

two trains daily through McNeil six days per week (no trains on Sunday.) This is

a classic example of a lightly used rail line that would motivate the

implementation of a cabin interlocker for the benefit of the busier line (I-GN).

Second, and more significant, I-GN's response states that T&NO train crew

operated the levers "...outside the assigned tour of duty of the Agent."

This passage isn't precisely worded, but it could be interpreted to assert that

there has been an Agent at the tower "...ever since the T&NO cabin

interlocking was placed in service..." in July, 1928. The fact that the

Agent had telegraphy duties implies that the tower was being used to convey

orders to passing trains. Most likely, this was already being done by a

telegrapher at the I-GN depot across the diamond, hence the telegrapher simply

relocated to the new facility and took on the additional duties of leverman, moving the interlocker

controls four times per day (twice for each passage of a T&NO

train.) The fact that the agent was an MP (I-GN) employee does not call into

question RCT officially listing the H&TC as the railroad that operated the

cabin. H&TC (actually, T&NO) train crews were ultimately responsible for

operating the controls, but the duty was handled for them by the agent when he

was on duty. That the railroads chose to incorporate an "agent-telegrapher-leverman"

employed by I-GN was not an RCT requirement for the commissioning of Tower 132.

Many manned towers were not staffed

24/7/365. During unstaffed periods, the signals were left positioned to grant

"Proceed" indications on the busier line. Train

crews on the other line encountering an unstaffed tower would either summon the

tower operator by telephone to operate the controls (e.g.

Tower 33), or they would enter the tower and

operate the controls themselves (e.g. Tower 62,

where the railroads converted a manned tower into a cabin interlocker simply by

declaring it so and eliminating its staffing.) As a cabin interlocker, the default position of the signals at McNeil was to allow unrestricted movement

on the I-GN line, but unlike most cabin interlockers, Tower 132 was staffed

during the day six days per week and closed on Sundays. The reason the Union

won its case at McNeil was because the railroads' existing agreement required

the use of a Union employee six days per week. The Federal law that lowered the

standard work week for "non-operating" railroad employees from 48 hours to 40

hours on September 1, 1949 did not affect the agreement since it could still be

honored by hiring additional employees.

|

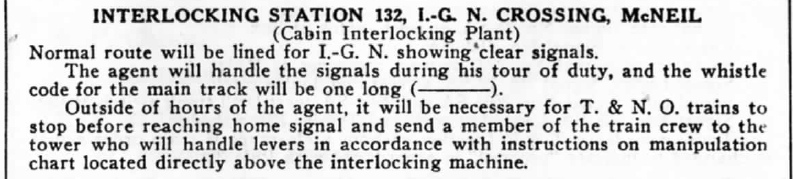

Left:

These instructions from a June, 1940 T&NO Employee Timetable explain to

train crews that they will need to operate the Tower 132 interlocker

when the agent is not on duty. Elsewhere, the timetable lists the duty

hours for the agent at Tower 132 as 8:00 am to 5:00 pm "Daily Except

Sundays and Holidays" and "8:00 am to 10:00 am" on Legal Holidays. The

tower was closed on Sundays. These instructions remained unchanged in a

Special Instructions supplement issued by T&NO in December, 1959.

Historic aerial imagery shows both the cabin and the depot removed

between 1967 and 1973. |

Above Left: Returning to the

scene in the photo at the top of page, SP #6607 has

almost reached the tower. Above Right:

SP #6607 crosses the diamond adjacent to the MP depot. The depot sat in the west

quadrant, diagonally across from tower. Note the corner of the tower's roof

barely protruding into the image from the left edge. (both photos, Roger Schull

collection)

Four mid 60s photos courtesy Roger Shull

collection:

Above Left:

A southbound MP locomotive crosses the diamond while SP's train waits in the

siding. Above Right: a

northeast view along the MP tracks Below

Left: In this south view of the crossing, the Tower 132 cabin at

left is mostly obscured by electrical cabinets.

Below Right: Facing northwest along the SP tracks, a

northbound Texas Eagle passenger train speeds across the diamond past Tower 132.

Above:

This photo, credited to Jim Hickey from the David M. Bernstein collection,

appeared in the Summer 2019 edition of S P

Trainline. The caption was:

"Operating as Extra 162 West,

a train of empty cars for rock loading is crossing the Missouri Pacific diamond

at McNeil. The station was owned, maintained and operated by the MP. A joint

agency was maintained by the railroads by agreement effective November 1, 1911,

with each company paying 50% of the building maintenance and T&NO paying

one-third of the operating costs. The small building to the left is Interlocking

No. 132 which was owned, operated and maintained by the T&NO. This was a cabin

interlocking normally lined for Missouri Pacific movement. When on duty, the

agent handled the interlocking signals, otherwise T&NO trains were required to

stop before passing the interlocking signal and send a crewman ahead to operate

the interlocking for their route using a manipulation chart displayed above the

interlocking machine. After completing their move the T&NO crew would restore

the route for the Missouri Pacific."

The photo is undated, but it

certainly appears to have been taken in the mid 1960s. The view is similar to

the photo of SP #6607 crossing the diamond except that here, the camera is west

of the T&NO tracks instead of east. In both photos, the T&NO train is northbound out of Austin. That the

agreement between the railroads dated back to 1911 lends credence to the idea

that the joint agency telegrapher handling train orders at the station moved to

the new cabin when it was erected in 1928 and took on additional duties as the leverman.

Above: These two images from

1966 (left) and 1965 (right)

show operations at the McNeil crossing. In June, 1966, two crewmen on a

northbound MP freight are leaning out to catch train orders as they pass the

station. In August, 1965, this SP local freight is finally crossing the diamond

northbound after a lengthy delay during which MP's southbound Texas Eagle

passenger train was waiting in the distance. (both photos (c) J. Parker Lamb,

2016, Center for Railroad Photography and Art)

The H&TC was fully merged into the T&NO in 1934. The T&NO lasted

until 1961 when it was fully merged into SP. In 1986, SP sold the former A&NW route to the City of Austin which

wanted to preserve the right-of-way for potential commuter or light rail use.

The City

subsequently leased the line for freight operations to RailTex. Under RailTex,

a new Austin & Northwestern was created to be the operating railroad. In 1996,

the Longhorn Railroad took over operations on the line with freight service

beginning May 6th. Yet another operating change was made in April, 2000 when the

City leased the line to the Austin Area Terminal Railroad (AUAR reporting marks). Still owned by the

City, the line has been operated by the Austin &

Western Railroad (AWRR), a subsidiary of transportation services company Watco,

since October 1, 2007.

|

Left:

When the cabin was removed (late 60s or early 70s), the

interlocker controls were moved to a post-mounted box.

Brakeman Jon Pederson has opened the cover door and is preparing to

unlock the derail switch handle. The target in front indicates the

derail position (open). The silver interlock is linked to UP's traffic

dispatcher. When UP has a train in the block, a small semaphore

indicator on top of the control stand is in the 'up' position. After the AUAR train goes through,

the interlock is reset to pass UP traffic. The instruction board has

"Southern Pacific" scratched out in several locations, i.e. it was

most likely the same arrangement when control box was installed. (John A. Pearce,

January 7, 2005)

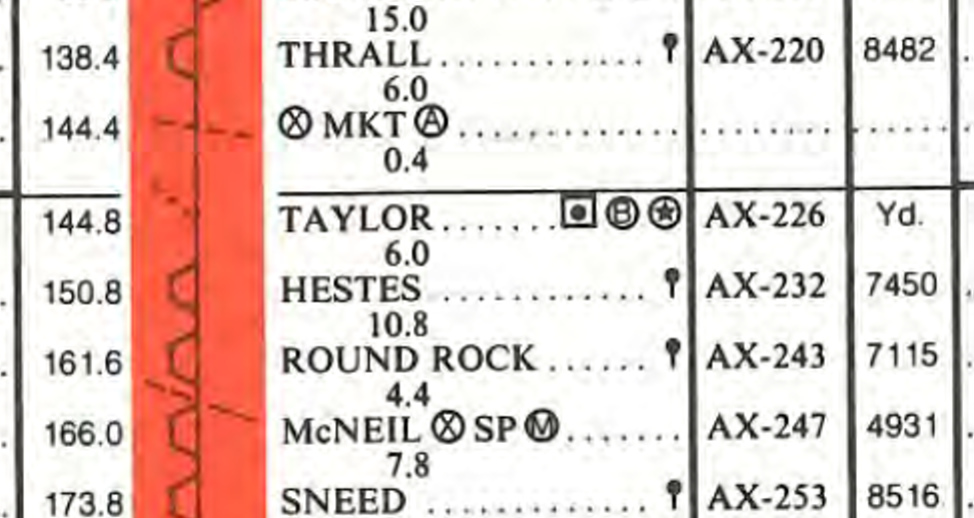

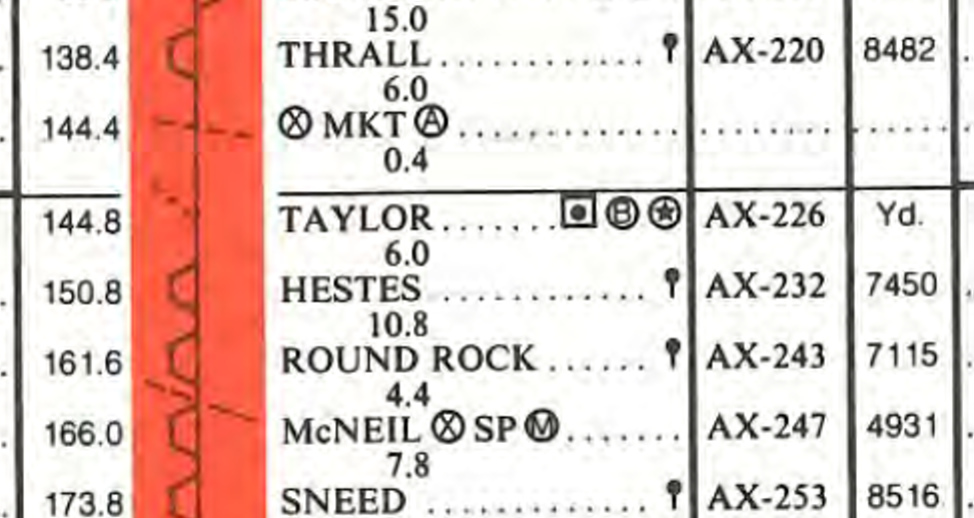

Below:

This 1985 MP employee timetable shows the SP crossing at McNeil with a

circled M to indicate a mechanical interlocker. Compare with the MKT

crossing 0.4 miles east of Taylor, which shows a circled A, for an

automatic interlocker.

|

Control posts such as this one were commonly used

as replacements for cabin interlocker huts. With the box only able to be opened

by authorized train service personnel, huts could be eliminated, with the

controls moved to a post and the interlocking electronics moved to a trackside

cabinet. For other examples, see Tower 103,

Tower 70 and Tower 64.

At Tower 127, the control boxes were mounted on the

side of the interlocker cabinet instead of a post.

Four photos taken January, 2005 by John A.

Pearce; thanks, John! Above Left:

Austin Area Terminal Railroad locomotive AUAR 190 is switching the UP

interchange track. Unit numbers 190 and 191 are a pair of GP-40s that had been

recently acquired by AUAR. The conductor on the rear of the locomotive is Eric

Hamilton. Above Right: Looking

west, the grass covered cement rectangle is the old foundation for the Tower 132

cabin. The UP mainline is in the foreground, with north to the right, crossing

McNeil Store Rd. In the background is the company store for the Austin White

Lime Co. Their limestone products plant has been located in the north quadrant

of the McNeil diamond since 1888, and may have had rail service from the very

beginning.

Below Left: A southbound UP

light engine hop passes Austin White Lime led by an old Cotton Belt engine.

Below Right:

Austin White Lime had a front loader with a railroad coupler attached to the rear,

known to all as "the McNeil Switcher". They routinely used it to push covered hoppers into place from

their UP interchange track.

Clifton Jones provides the following details about the interlocker at McNeil.

The interlocking device was

usually operated by an SP trainman (later A&NW, Longhorn, Austin Terminal, etc.)

There was a locked box, that once it was opened would set off a timer, and an

unlocking device for the derail, and also set the home and distant signals for

the MP (UP) approaching the interlocking. After a period of about 9 minutes, the

timer on the cabinet would unlock the derail and the trainman could throw the

split derail switch for the train on the SP to proceed. It set the home signal

for the SP to ‘lunar’ so the train could proceed at restricted speed. Once the

entire train had cleared the interlocking limits, the derail could be restored

to derail position and the lock box on interlocking device was closed and

locked.

Austin's plan to use the A&NW right-of-way for commuter transit evolved into Capital MetroRail, a commuter rail system that

began operating in 2010 between Leander and downtown

Austin, sharing the freight tracks along much of the

route. At McNeil (above left), commuter

trains pass over the

UP tracks on a bridge whereas AWRR freight trains continue to

cross UP at grade at the Tower 132 site. (photo by Rickey Green/CapMetro)

Above Right: Looking south from the McNeil Rd. grade

crossing, the right track elevates onto the bridge that carries Cap Metro

commuter trains over UP's tracks at McNeil. The left track is used by AWRR

freight operations to cross UP's tracks at grade at the former Tower 132 site.

In 1988, the

Austin Steam Train Association

(ASTA) was formed as a non-profit organization to rebuild SP #786, a

steam locomotive that had been donated to the City of Austin in 1956. The

rebuilt engine pulled its first excursion train northwest of

McNeil between Cedar Park and Burnet on July 25, 1992. Operating as

the Austin & Texas Central Railroad, the ASTA continues to offer

excursions to the public. While SP#786 is undergoing a complete rebuild,

diesel locomotives provide substitute power.