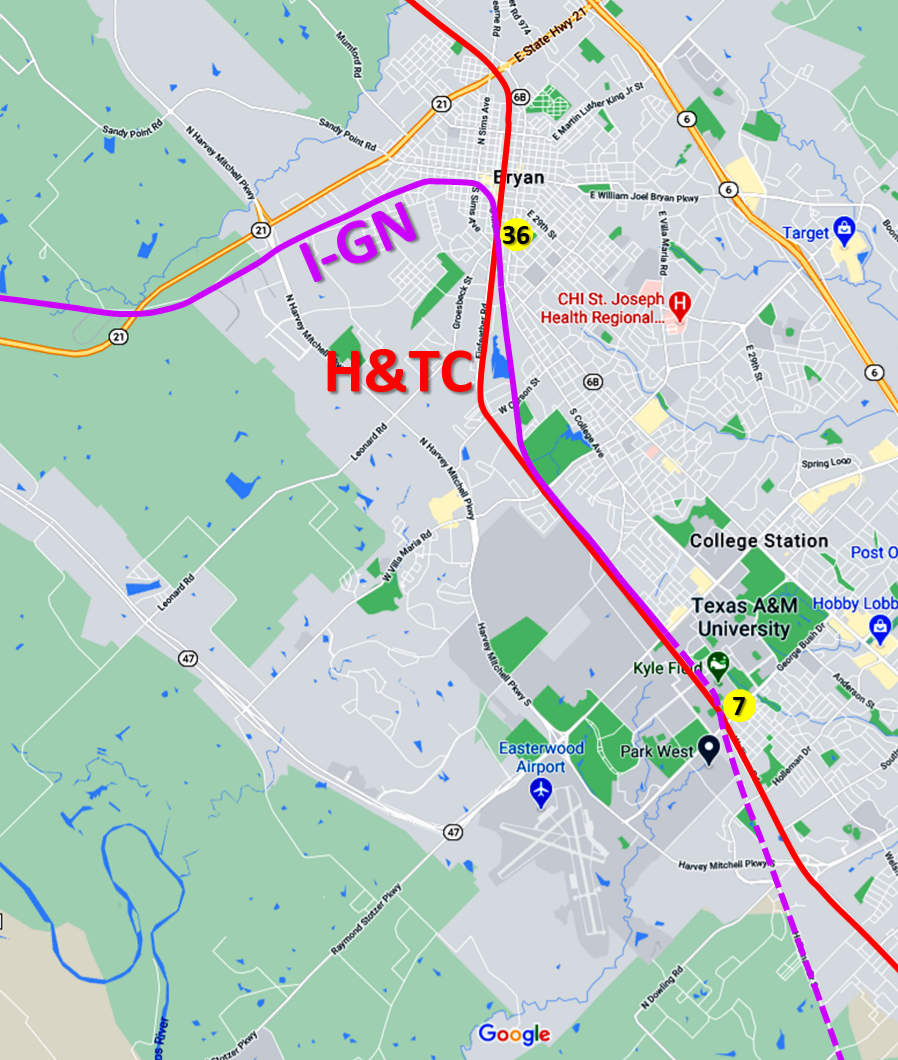

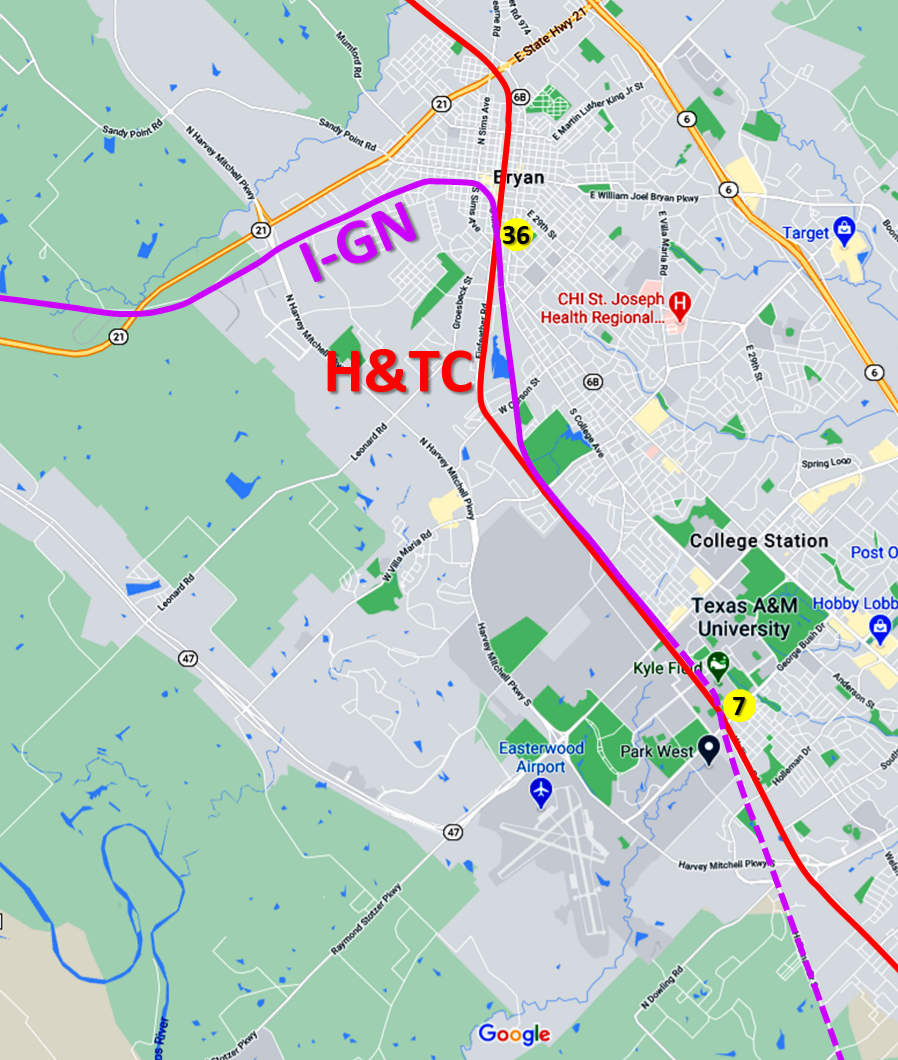

Texas Railroad History - Tower 7 (College Station) and Tower 36 (Bryan)

Two Crossings of the International & Great Northern Railroad

and the Houston & Texas Central Railway Five Miles Apart

Above Left: This snippet

of a larger 1929 aerial photo looking northeast at Kyle Field in College Station

shows Tower 7 at the bottom of the image, just across from the baseball grandstands.

The football game at the Kyle Field stadium explains the cars parked adjacent to the tower.

Above Center: Magnification confirms a staircase on the south side of the

tower. (Henry Mayo collection)

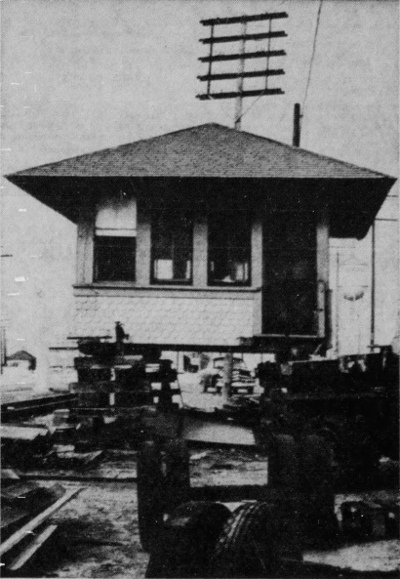

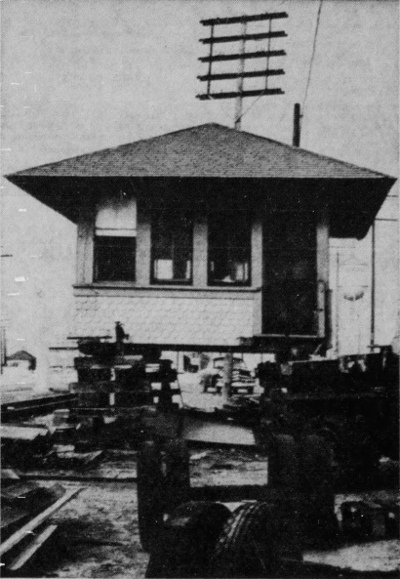

Above Right: The

Bryan Eagle of December 19, 1957 reported

on the dismantling of Tower 36 at Bryan so that it could be moved by its new

owner, Luther Cobb, to his property in College Station to be used as a

residence. Cobb was a claims agent for Southern Pacific (SP). The photo shows the upper story operations room isolated from the base floor. Clearly visible

is the traditional Queen Anne

architecture "fish scale" pattern used between the floors of virtually every SP interlocking tower in Texas (e.g.

Tower 17 and many others.) (hat tip, Henry Mayo) Below Left:

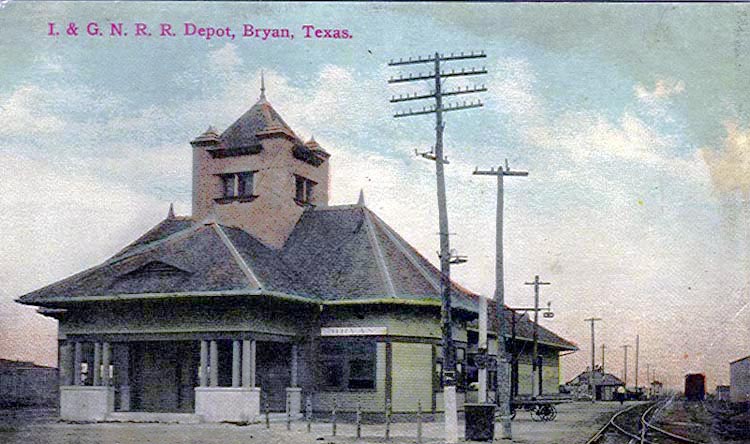

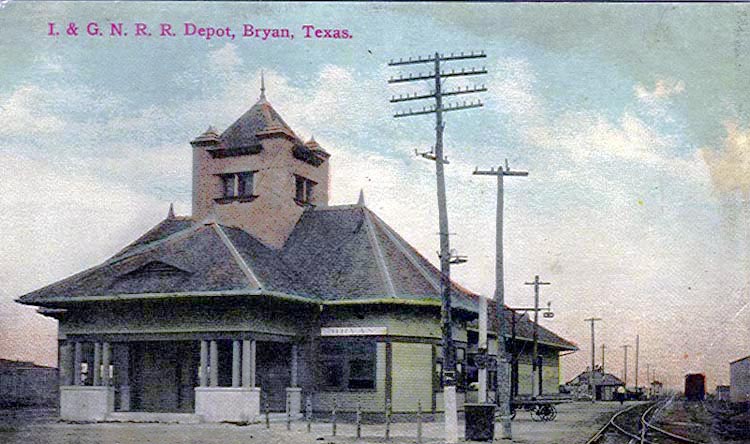

This postcard of the International & Great Northern passenger depot in Bryan

shows a faint view of Tower 36 beside the tracks in the distance.

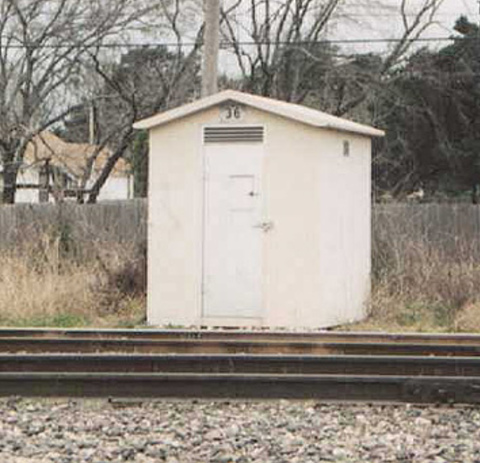

Below Right: The Tower 36

automatic interlocking cabin that replaced the manned tower in 1958 was still

standing forty years later (but has since been removed.) (Jim King photo c.1998)

The town of Bryan was founded in 1859 by the Houston &

Texas Central (H&TC) Railway as it built north through the area. It was named

for William J. Bryan, the landowner who donated the property for a townsite. He

was a nephew of Texas' founding statesman Stephen F. Austin. Construction

stopped south of Bryan at the community of Millican during the

Civil War. In 1867, the railroad finally reached Bryan and continued building north, completing tracks to

Denison near the Red River in 1873. At Denison, the

H&TC connected with the Missouri, Kansas & Texas Railway (MK&T, but commonly

known as "the Katy".) The Katy had built south from Kansas and

Missouri through Indian

Territory and bridged the Red River into Texas. Soon, the Katy and the H&TC were

collaborating on single train passenger service between Houston and St. Louis. The railroads exchanged freight at

Denison, creating a major route for exporting Midwest grain commodities through

the port of Galveston. In the early 1880s, the H&TC was

acquired by Southern Pacific (SP).

|

On

October 4, 1876, Texas Agricultural and Mechanical College (now Texas

A&M University) opened on 2,400 acres of land about five miles south of Bryan.

At least by 1878, the name College Station had been adopted for

the community, named for the railroad station adjacent to campus. As

there was literally nothing else in the vicinity and many Texans were

unfamiliar with the new school, the college ran advertisements in major

statewide newspapers periodically to announce upcoming semesters. The

college had no street address; it was simply "Railway Depot and Postoffice, College Station, Texas."

Left:

Galveston Daily News, August 10,

1880 |

The International & Great Northern (I&GN) Railroad had

been part of railroad magnate Jay Gould's vast collection of railroads since

1881, and he had named himself President of the I&GN. At the time,

it was the largest railroad in Texas. Upon his death in 1892,

his son George took over as President and began managing the I&GN and the rest

of the Gould empire. Like many other rail executives, George Gould preferred to do

new construction under a separate charter to isolate the main railroad from

any financial problems that might ensue. Thus, he chartered the Calvert, Waco and Brazos Valley

(CW&BV) Railroad to handle the construction of a new line he wanted to build, ostensibly

from the I&GN main line at Valley Junction north to

Waco and Fort Worth. Gould also

planned to extend this new line south from Valley Junction to

Houston but this was not reflected in the initial CW&BV charter. The charter was revised on

May 6, 1900 to make Bryan the southern terminus instead of Valley Junction, but

Gould quickly realized this would serve little purpose. From Bryan, a trackage

rights agreement with the H&TC would be needed to reach Houston, but there was

little possibility that a deal could be made as this would be against H&TC's

self-interest. The charter was revised again in December, 1900 to move the south

endpoint to Spring, just north of Houston on the

I&GN main line between Houston and Palestine.

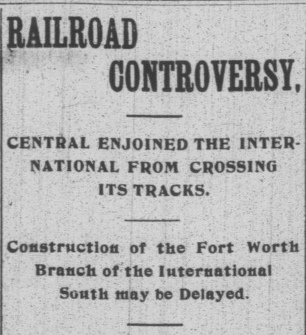

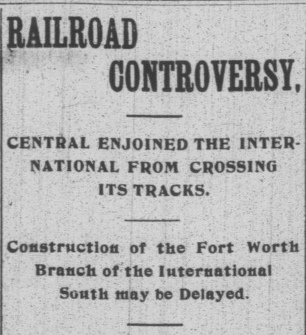

Right: The CW&BV construction commenced in 1901

and went as far south as Bryan, but it quickly ran into problems with

the H&TC. An article under this

headline in the Navasota Daily Examiner

of September 3, 1901 discussed a restraining order the H&TC had obtained

against "the International" to prevent additional crossings of its

tracks (it was public knowledge that the CW&BV

was a "construction arm" of the I&GN.)

The H&TC objected to the entire enterprise because it would result in

the I&GN serving many communities already served by the H&TC, and

because their south endpoints would be the same: Houston.

The

CW&BV had already built across the H&TC at Bryan and had decided to

do so two more times, at College Station and

Navasota. The article spoke highly of the trackwork that had already

been accomplished, noting that the line between Bryan and College

Station "...is free from curve and nearly 2,000 feet shorter than the

Central..." The article also explained that the location

chosen by the I&GN for the College Station crossing was "...almost level, and

one at which Houston and Texas Central trains have stopped for a number

of years to make the sidings at the college for the meeting of trains."

The H&TC had no legal right to prevent the I&GN's construction. Its

claim was that Gould was building the line through the area simply to

harass the H&TC, a dubious theory which did not stand with the Court. I&GN claimed to have been trying to work with the H&TC

but to no avail, pointing out that it had "...suggested the building of

union depots at College and Navasota, and the Houston and Texas Central

absolutely refused to cooperate..." The restraining order was lifted and

in 1902, the I&GN formally took over the effort and finished the tracks through College Station and Navasota to the I&GN main line at

Spring. Whereas the I&GN tracks between Bryan and College Station were shorter

than the H&TC's, its route from College Station to Navasota was longer, swinging well west of the H&TC right-of-way,

closer to the Brazos River. |

|

In the opposite direction, the I&GN built from Valley

Junction northwest to Waco (41 miles) in 1902, continuing 95 miles to Fort

Worth in 1903. This completed the I&GN's new Fort Worth Division between Fort

Worth and Spring. This was a reasonably direct route so it should have

positioned the I&GN to compete favorably for Fort Worth - Houston traffic

against SP, Santa Fe and the Katy. Instead, the route had major issues, as author

Wayne Cline described in his book

The

Texas Railroad ((c) Wayne Cline, 2015)...

...the Fort Worth Division was built

with "rapid-fire" techniques, which were not noted for producing safe and

durable results. By 1902 short trains were rocking slowly along the wavy tracks

of the new Fort Worth Division, and the following year found them creeping over

a new 45-mile branch between Navasota and Madisonville."

|

Through Bryan and College Station, the I&GN paralleled

the H&TC and crossed it twice at acute angles: on the south side of

College Station and near downtown Bryan. Interlocking plants were

planned and subsequently approved at both locations by the Railroad

Commission of Texas (RCT.) Internal SP records show that the planning

for the College Station interlocking occurred much earlier than might be

expected. An internal SP summary document for the anticipated

interlocking

is dated October 23, 1901, only eight days after the first

public hearing ever held by RCT

pertaining to the implementation of the new state law (effective three

months earlier on July 1) granting authority to govern modes

of crossing and safety requirements such as interlocking plants. RCT's

order on November

8, 1901 required railroads to implement swing gates as an

interim measure until RCT could publish rules and regulations governing

the design, installation and inspection of interlockers.

In May, 1902, RCT adopted formal rules

for

the process by which tower and interlocking plant designs would

be regulated and approved. At the end of 1902, RCT's Annual Report

included College in a list of priority locations to be

interlocked in 1903. By then, the consultation process between

RCT and the two railroads at College Station had been underway for many

months and the new plant was imminent. Tower 7 was commissioned for operation at

College Station on

February 21, 1903.

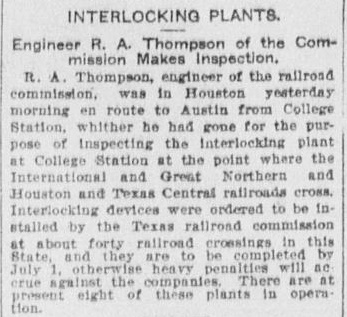

Left:

The Houston Daily Post

of February 22, 1903 reported RCT's approval of the new interlocker at College Station.

On the same day, the Bryan Eagle

published a news item quoting a story from the prior day's

Navasota Examiner

... "Charles Smith in charge of the

works here went to College Station today to put into operation the

interlocking switch plant recently installed there. The state railroad

commission is to be present at the test to pass officially on its

efficacy."

|

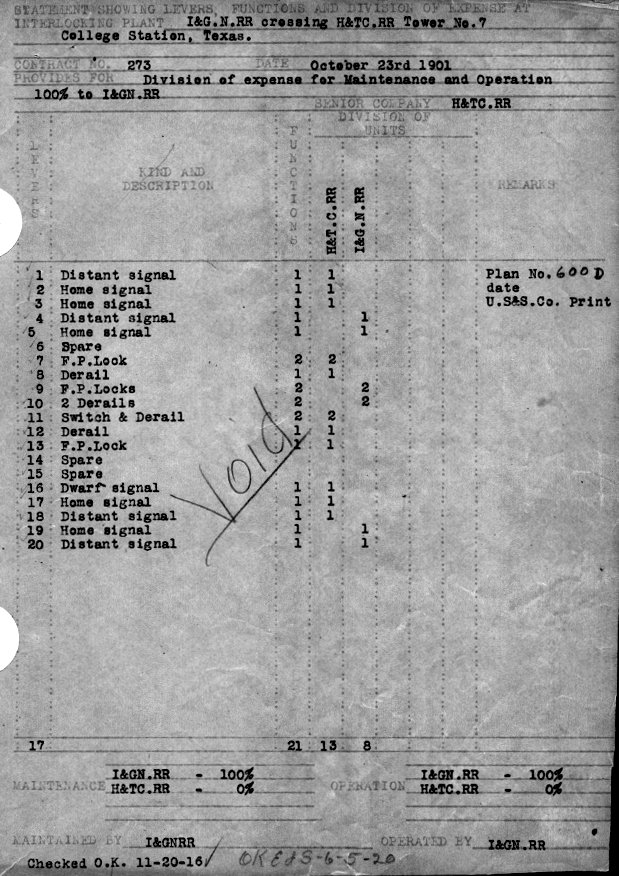

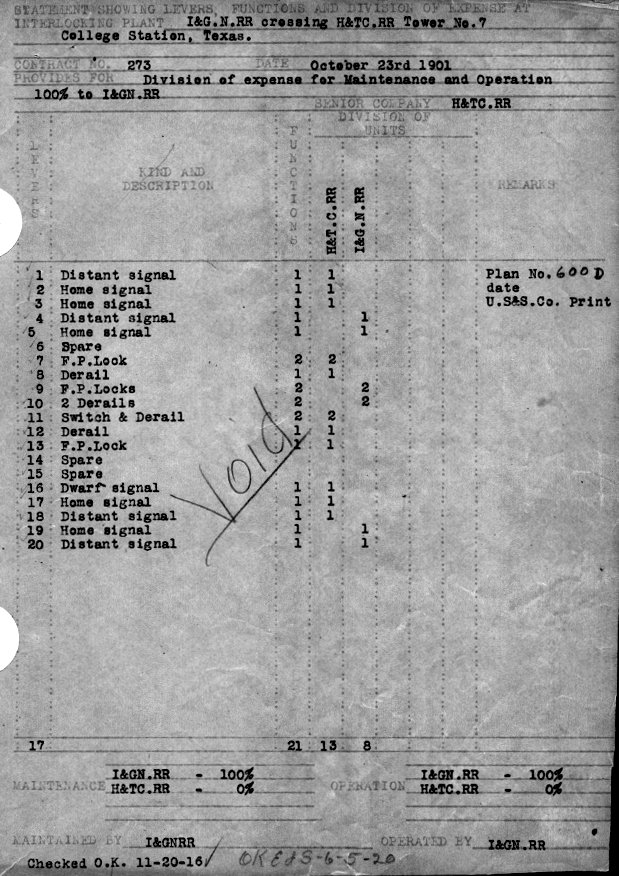

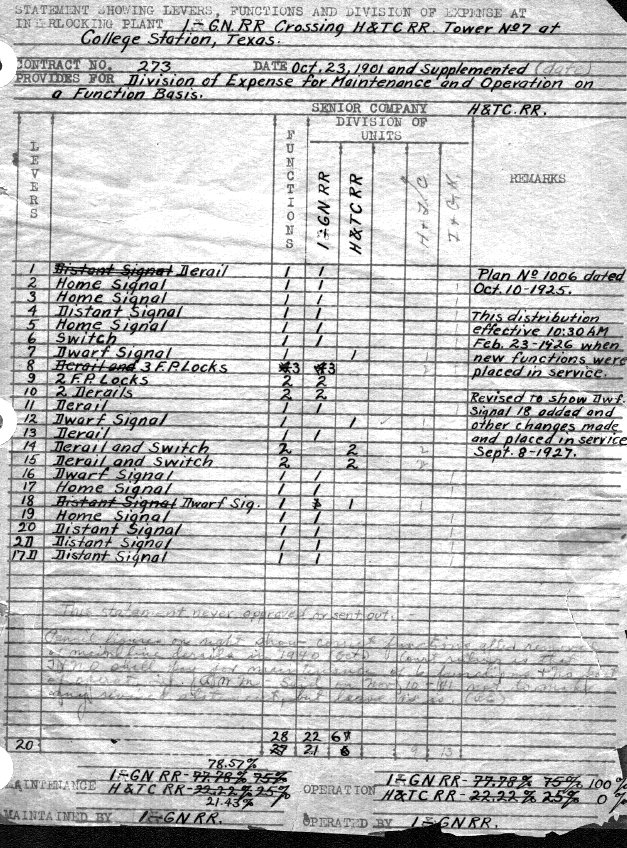

SP created an internal single-page form known as a D-205

Drawing for each interlocker at which it was a participating railroad. The form

provided a list of the interlocking function assignments and a specification of the share of recurring Operations and Maintenance (O&M)

expenses owed by each railroad. The form had the lengthy title

STATEMENT SHOWING

LEVERS, FUNCTIONS AND DIVISION OF EXPENSE AT INTERLOCKING PLANT.

The railroads sharing an interlocking tower would sign a contract allocating

various O&M responsibilities, designating how expenses would be divided and how

and when payments would be accomplished. Railroads were free to negotiate their own

arrangement for how they would share O&M

expenses, but most often they followed RCT's default rule to share on the basis of function count

ratios. Since every function in an interlocking plant could be attributed to one

of the railroads (or in some cases, both railroads, in which case each railroad

was credited with a half-function), the ratio of a railroad's function count

to the plant's total count became its function count ratio. Operating the tower and

performing maintenance activities were considered separate tasks. For most

manned towers, one railroad took the lead

for both, typically the railroad that designed and built the tower, and acquired

the interlocking plant.

The non-recurring cost of interlocking plants and

tower buildings was handled differently. For crossings that pre-dated the 1901

law, the railroads at the crossing shared the capital expenses evenly. For

crossings after June 30, 1901, the second railroad at the crossing, i.e. the one

that created it, was responsible for all of the capital expense. At least for

College Station, the I&GN tracks crossed after July 1, so the I&GN had to bear all

of the capital expenses. At the end of 1903, RCT

began publishing a comprehensive list of active interlockers within each annual

report. The first report identified Tower 7's interlocker as a mechanical plant

built by Union Switch & Signal Co. with 19 functions and 17 working levers.

Above Left: SP's original

D-205 Drawing (Carl Codney collection) for Tower 7 is dated October 23, 1901. It

was very common for interlocking function changes to be handwritten on these

forms along with other explanatory notes, but this form shows almost no

handwriting at all. Yet, it has notations at the

bottom indicating it was "checked" by SP personnel in 1916 and again in 1920,

suggesting that it was, indeed, the bona fide Tower 7 document. It also shows that

despite 13 of the 21 interlocker functions being assigned to the H&TC, the I&GN

is listed as responsible for 100% of the O&M expenses. Even a simple 50 / 50

split would have been rational, so why would the I&GN pay 100%? The most likely

explanation is that since the railroads would be sharing two interlocking towers

five miles apart, the I&GN took the O&M expenses for Tower 7 and the H&TC took

the O&M expenses for Tower 36 at Bryan which opened on April 22, 1904. This

would simplify their accounting by eliminating the need to track the O&M

expenses closely for monthly billing purposes for each tower. Consistent with

such arrangement, RCT's records show the I&GN responsible for operating Tower 7

and the H&TC responsible for operating Tower 36. The discrepancy between the 21

functions listed and the 19 functions RCT reported in its interlocker summary table dated December 31, 1903 remains unexplained. Tower

7's reported function count varied over the years from a low of 16 (1904 - 1915)

to a high of 30 (1927 - 1930) but specific changes are undefined. After December

31, 1930, RCT no longer published a table of active interlockers annually.

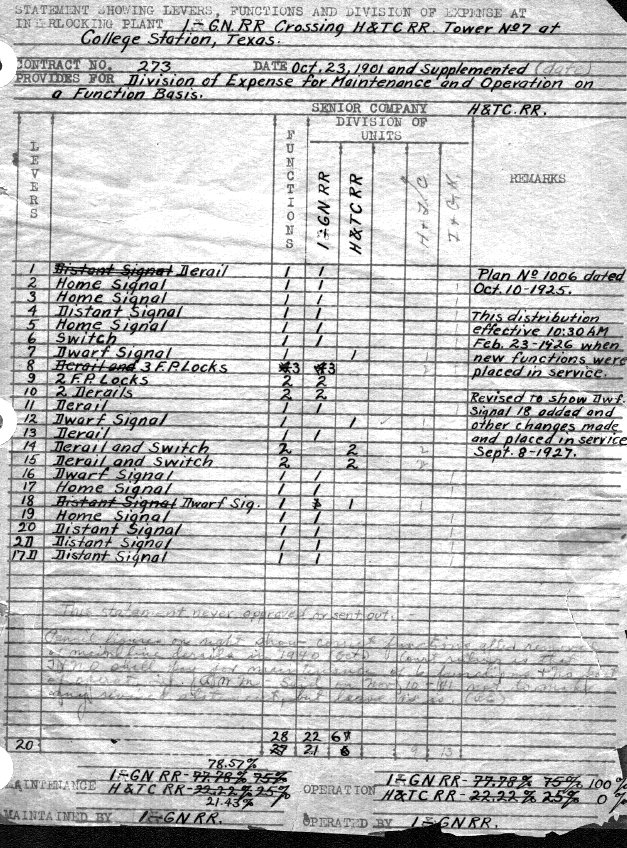

Above Right: This handwritten

version (Carl Codney collection) of the same document retains the original 1901

date but appears to have been created 24 years later to address a revised

interlocker design plan dated October 10, 1925. Notes in the REMARKS column

explain that the new functions were placed in service four months later on

February 23, 1926, and that additional changes were made in September, 1927. Two

additional columns were added in pencil in what appears to be a draft of another

set of changes. A notation across the bottom, also written in pencil, reads...

"This statement never approved or sent out. Pencil

figures on right show correct functions after removal of mainline derails in

1940 (Oct.) Court ruling is that T&NO shall pay for maintenance of 6 functions &

no part of operation. A M M said on Nov 10 - 41 not to make any revised

statement, but leave as is. (A E)."

...referencing the

Texas & New Orleans (T&NO) Railroad, an SP subsidiary to which the H&TC had been

leased. The court case referenced has not been identified.

In contrast to Tower 7,

Tower 36 at Bryan had a much smaller reported function count: ten, from 1903

through 1926. The count rose to 16 in 1927 and was unchanged after that. Like

Tower 7, Tower 36 was a mechanical interlocking plant, but RCT records note that

that the plant was "installed by" the H&TC whereas at Tower 7, the

plant manufacturer (Union Switch & Signal Co.) had performed the installation. The D-205 drawing for

Tower 36 has not been located so the precise definition of the functions remains undetermined. Tower 36 was substantially busier than Tower 7;

information provided by RCT in 1906 showed an average of 45 movements per day

past Tower 36 compared to only 23 at Tower 7.

In 1927, SP began

consolidating its Texas and Louisiana railroads into the Texas & New Orleans

(T&NO) Railroad, a long time SP subsidiary operating mostly in

Houston, east

Texas and Louisiana. SP leased the H&TC to the T&NO at that time and then fully merged the

H&TC into the T&NO in 1934. The T&NO was dissolved in 1961 and all of its assets

were merged directly into SP.

Whereas the H&TC had remained within the SP

railroad family since the 1880s, the I&GN had experienced a much more difficult path to stability. It

went into receivership in 1908,

partly from economic conditions and partly from financial miscalculations made

by George Gould pertaining to railroad investments elsewhere in the U.S. Gould

issued a statement blaming the receivership on orders issued by RCT mandating large expenditures to improve the I&GN's infrastructure

and service.

RCT stuck to its order, though it was roundly criticized throughout the railroad

industry. While other railroads were ordered to make similar improvements, RCT

rightfully had very serious concerns about the I&GN. The tracks through

Bryan and College Station were part of I&GN's Fort Worth Division, the newest

track construction in its network. Though it was new and accounted for only a

quarter of the company's mileage, the Fort Worth Division was the primary culprit

in the I&GN's difficulties. Author Wayne Cline explains that after George Gould had taken control in the wake of

his father's death in late 1892...

"...the International and Great

Northern had compiled a reasonably acceptable safety record, but it went rapidly

downhill shortly after the Fort Worth Division was constructed. In 1904,

casualties suddenly soared when 139 workers and passengers were injured --

almost twice the average for the previous ten years. ...[in 1908] Commission records

showed that 99 wrecks had occurred on the I&GN since the summer of 1907, and 41

of them occurred on the newly laid track of the Fort Worth Division."

Emerging from bankruptcy in 1911, a new I&GN company

was organized to take over the assets and operations of the old company, with

the Gould family still in charge. In early 1914, the I&GN again returned to

receivership, this time for several years which included the period under the U.

S. Railroad Administration during World War I. Another new company with a

slightly different name, the International - Great Northern (I-GN) was formed in

1922 to acquire the I&GN out of foreclosure, at which point the Gould family

connection to the I&GN ended forever.

The I-GN's financial

reorganization coupled with its service to many of the major cities in Texas and

its thousand miles of track made it an attractive

target for acquisition. Missouri Pacific (MP) had gained its own independence from the Gould family in 1917

and wanted to buy the I-GN to re-enter the Texas market ("re-enter" because

under Gould's command, MP had leased the Katy in 1880 to gain a foothold in

Texas, but the lease had been abrogated by the Texas Supreme Court in 1890.)

MP's proposed purchase of the I-GN was nixed by the Interstate Commerce

Commission (ICC). Going to Plan B, MP helped the New Orleans, Texas & Mexico

(NOT&M) Railway buy the I-GN.

The NOT&M was originally among a collection of

ostensibly independent railroads

operating between New Orleans and Brownsville sharing the moniker Gulf Coast

Lines (GCL.) The railroads had been managed collectively by executives of

the St. Louis & San Francisco ("Frisco") Railway and a syndicate backed by the

St. Louis Trust Co. The Frisco's

receivership in 1914 resulted in the bankruptcy judge choosing the NOT&M to

become the corporate parent for all of the GCL railroads through common

ownership under the St. Louis Trust Co. syndicate. The

ICC approved NOT&M's purchase of the I-GN in 1924 and then allowed MP to buy the NOT&M on

January 1, 1925. This gave MP the I-GN plus all of the NOT&M railroads -- a

sudden and massive presence for MP in Texas. In 1933, MP went into a lengthy

receivership which likewise compelled a receivership for its I-GN subsidiary.

Operating for more than two decades under court supervision, MP finally emerged from bankruptcy in 1956. MP dissolved the I-GN

at that time and integrated

its operations under the MP name.

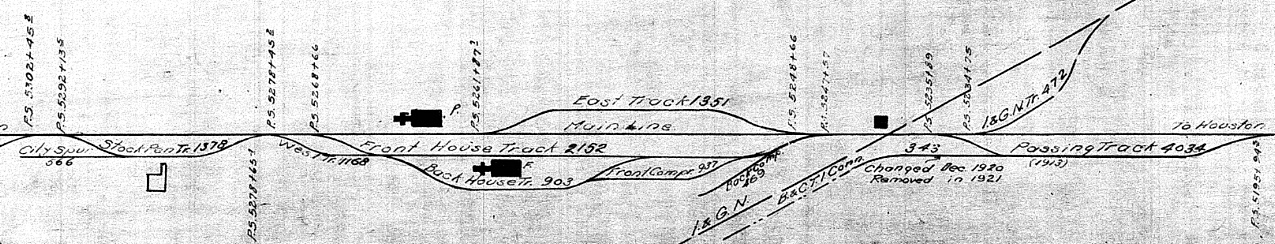

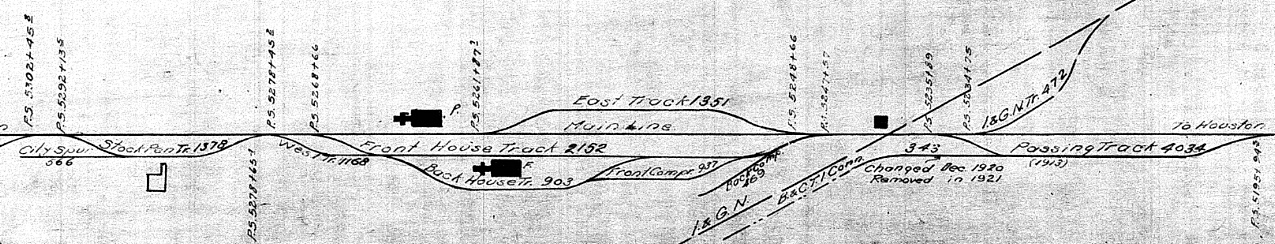

Above: Oriented with College

Station to the right, this image snippet from a 1926 T&NO track chart of Bryan

(Carl Codney collection) uses a dark square to represent the location of Tower

36 east of the I-GN / H&TC crossing diamond. The other two dark objects are SP

depots. The freight depot is between the Front House track and the Back House

track. The passenger depot is beside (east of) the main line. The chart shows

an "I&GN Tr." (transfer) track south of the diamond. The H&TC had been in Bryan

for three decades by the time the I&GN arrived, so it is not surprising that

many businesses had built along the H&TC main line to gain the advantage of rail

service. The I&GN did open some new areas for service in town, but it was not

positioned to overcome SP's advantage for local freight traffic.

|

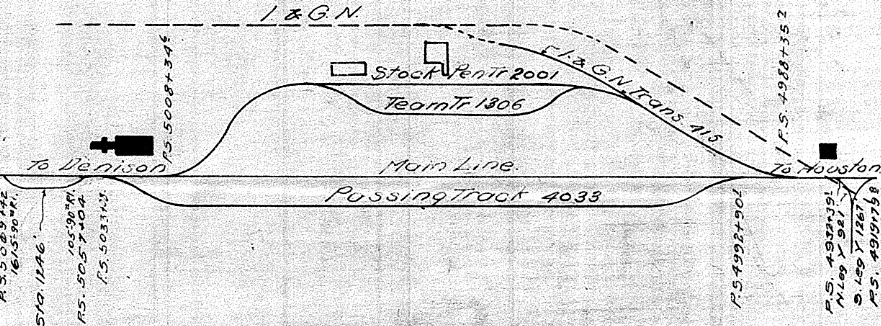

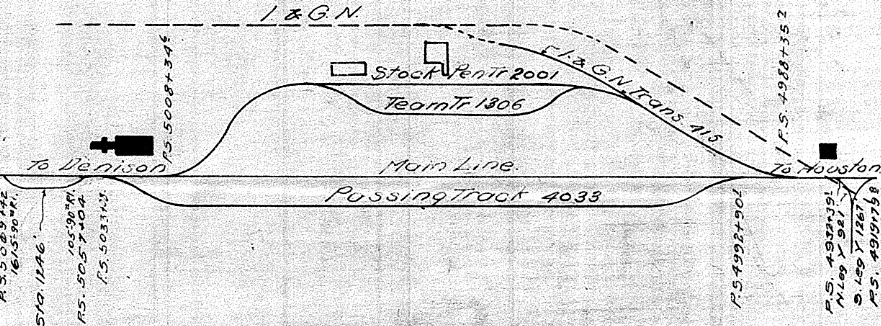

Left: This

1926 T&NO track chart of College Station (Carl Codney collection) uses a

black square to represent Tower 7 at the H&TC / I-GN crossing. Bryan is

to the left, Navasota to the right. The H&TC passenger depot is the dark

object to the left. A wye track and the I-GN transfer track both

intersected the main line near the crossing diamond. Switch, derail and

signal controls for these tracks may have been the reason that the Tower

7 interlocker had more functions than Tower 36. |

A 1952 T&NO Employee Timetable shows Tower 7 and 36

both having "continuous" office hours, i.e. they were manned 24 / 7. This may

seem obvious for a manned tower, but in some places (e.g.

Tower 33), towers had begun to close

for specified periods on a regular schedule (e.g. lunch hour, overnight, Sundays were

common.) Railroads began to reduce staffing further to save money, and some towers

opened only for a basic "day shift", leaving the signals lined for

the busier track at all other times. A telephone was accessible nearby if a train on

the other line needed to call an operator at home to come in and change the

signals. This approach worked to reduce staffing costs, but it was only

effective at select locations where one of the tracks had limited traffic.

Neither Bryan nor College Station qualified.

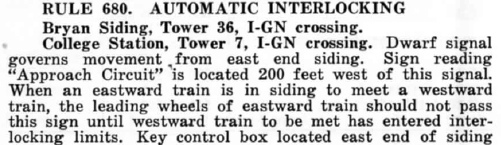

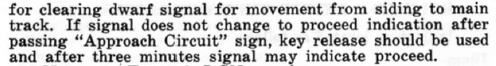

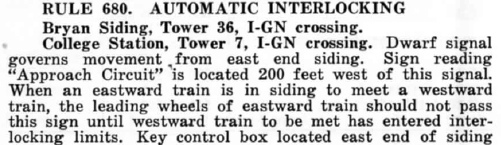

Right:

This paragraph appeared in T&NO's Employee Timetable supplement

Dallas and Austin Divisions Special

Instructions No. 5 effective December 6, 1959. By this date,

both towers had been converted to automatic interlockings.

SP records show that on June 14,

1956, a plan for an automatic interlocker to replace Tower 7 was created.

Documentation shows that the plan was revised on September 26, 1960 and the

revised plan became effective on November 8, 1960. It is undetermined precisely

when the Tower 7 building was removed, and its fate has not been

determined. The Tower 36 interlocker was converted to an automatic system in

1957 and the tower structure was relocated on

January 5, 1958. In 1965, MP and SP agreed to share the SP line south from College Station to Navasota. This allowed

the former I-GN line to be abandoned between Tower 7 and Tower 9,

with the tracks through College Station and Bryan operated jointly by

both railroads. Union Pacific (UP) acquired MP in 1982 and merged with

SP in 1996. All of these tracks are now owned by UP. |

|

|

Left: The H&TC line

went northwest out of Bryan and continued to Hearne while the I-GN swung

due west out of Bryan and then curved north to Valley Junction, crossing

another SP line at Tatsie en route. To the

south, both lines went to Navasota, but the I-GN tracks were removed in

1965.

Above: ex I-GN tracks

on 27th St., Bryan (Google SV)

Above: I-GN Rd.,

College Station (Google Street View)

Above: Google Street

View projects the "I-Gn Rd" name onto the pavement in this straight

stretch of former grade south of College Station. The I-GN right-of-way

was probably one hundred feet wide. |

Below:

Although tracks exist in all four directions, Google Street View from December, 2019 shows that there is no longer a

crossing at the site of Tower 36. Looking south down the former SP right-of-way,

the track coming north from College Station curves to the northwest to join the

former MP right-of-way instead of crossing over the MP as it previously did. The track on the former MP

right-of-way coming north (where railcars sit at left) from College Station continues straight across as it always did, but a switch has been added to

connect to the track on the former SP right-of-way to Hearne.