Texas Railroad History - Tower 11 (West Orange) and

Tower 125 (Mauriceville)

The Story of the Orange &

Northwestern Railroad

|

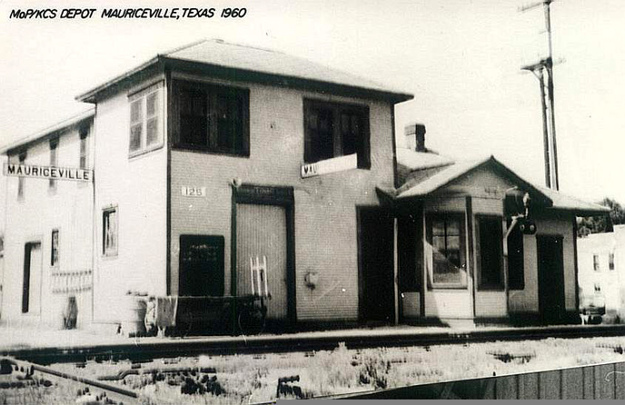

Left: This photo was taken by

John W Barriger III from the rear platform of his business car as his

train passed through Mauriceville heading southwest toward Beaumont,

probably in the 1930's. Barriger's camera was facing northeast along the

perfectly straight Kansas City Southern (KCS) tracks toward DeQuincy,

Louisiana. The photo is provided by the John W Barriger III

National Railroad Library, and its administrative identification in the

library indicates that Barriger's car was at the rear of a

Missouri Pacific (MP) train traveling the main line of MP's Gulf Coast

Lines (GCL) subsidiary which it had acquired in 1925. Barriger's train

is exercising MP trackage rights inherited from the GCL to use the KCS

tracks between

DeQuincy and Beaumont. The rights dated back to 1905 and provided a key segment of the GCL route between Houston and New Orleans that

competed with Southern Pacific's Sunset Route.

In the photo, Barriger has

just passed over the Orange & Northwestern (O&NW) Railroad. The O&NW and

KCS tracks crossed at a right angle in an X-pattern, with the depot

located in the quadrant north of the diamond. The O&NW had become a GCL

railroad in 1905, hence it was an MP railroad at the time of Barriger's

trip. The "125" placard on the side of the building announces that the

Tower 125 interlocking plant is located and operated inside, managing

what had become a KCS / MP crossing where MP also had rights on the KCS tracks. |

|

|

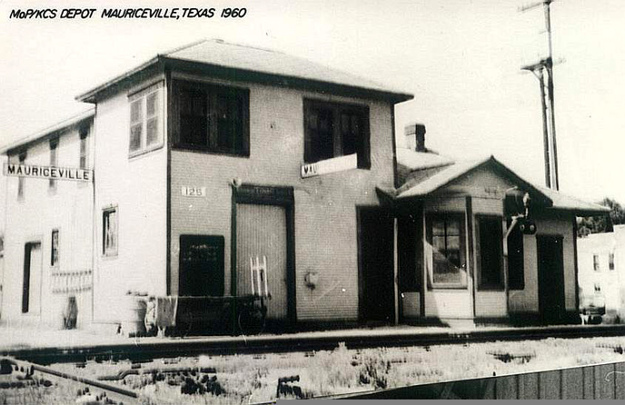

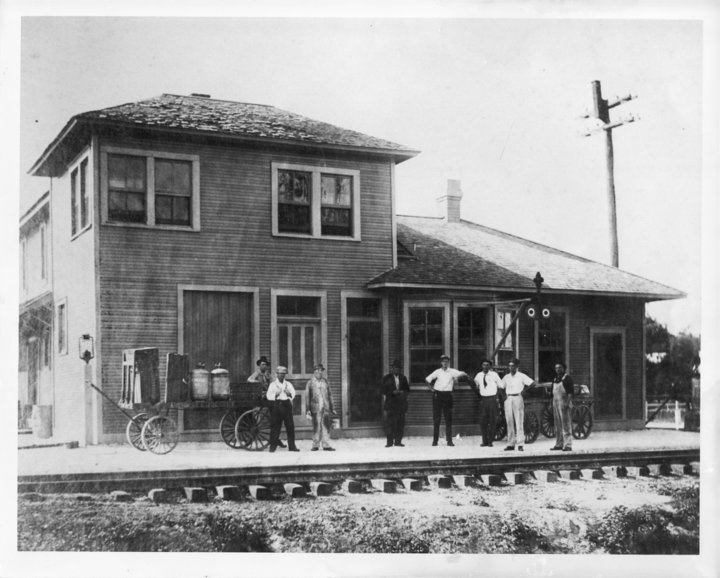

Above Left: 1960 image of

the depot at Mauriceville (H D Connor collection)

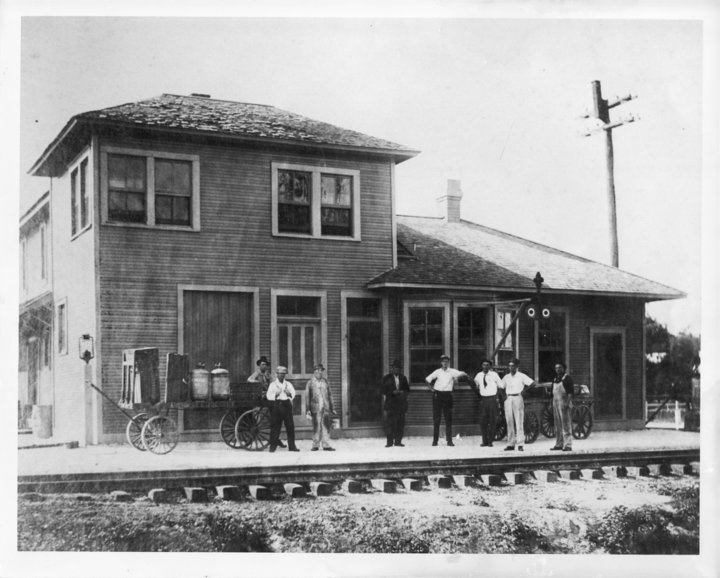

Above Right: Mark St. Aubin supplies

this undated photo of the Mauriceville depot viewed along the KCS tracks toward Beaumont.

Note that the road in the distance behind the depot is now FM 1130. None of

these photos show Tower 11 at West Orange because no photos of Tower 11 have been

found.

The story of the Orange & Northwestern (O&NW) Railroad

begins in 1877 when two

Pennsylvania men, Henry Lutcher and Bedell Moore, toured the massive yellow

pine forests of Louisiana and east Texas. They decided to build a sawmill at

Orange, a town so named because it was in Orange County. The town's original

name, Madison, was dropped due to confusion with another Texas town,

Madisonville. Orange was chosen to be the site of the sawmill because

it was centrally located among the areas to be logged, and only a short, navigable distance from the Gulf of Mexico on the Sabine River, Texas' border with Louisiana. The Sabine offered a means of getting logs to the mill by

floating them downriver from the forests north of Orange. When the mill opened in 1877, Lutcher and Moore named it

the

Star & Crescent Mill; it was the largest sawmill in Texas at the time. The

Texas & New Orleans

(T&NO) Railroad passed near the mill and may have been used during the

mill's construction to bring materials from the port of

Galveston. Proximity to mills in both Texas and

Louisiana combined with T&NO rail service and the Sabine River's outlet to the

Gulf of Mexico enabled Orange to become the

primary shipping gateway for lumber and other wood products along the Gulf Coast.

Prior to the Civil War, the T&NO railroad had been chartered by a lumber company

- a recurring theme in this story - for the purpose of connecting southeast

Texas with the port of Galveston. Three years later, in 1859, the T&NO name was

adopted when the vision for the railroad shifted to establishing a rail line between Houston and New

Orleans. By 1860, tracks had been laid between Houston and

Orange, and as the Civil War commenced, the T&NO briefly became a military supply line.

The condition of the

tracks deteriorated quickly, and in the

post-war years, there was only intermittent service on short track segments for

brief periods. Eventually, the line was rehabilitated and reconstituted into

a new company under the T&NO name. The first post-war train between

Houston and Orange operated in November, 1876. In 1880, the T&NO commenced

scheduled service between Houston and New Orleans through Orange, providing a

critical outbound transportation service for the wood products produced by the

Star & Crescent Mill. By 1881, the T&NO had become attractive to Southern

Pacific (SP) which acquired it to be part of the Sunset Route, a southern transcontinental

line

SP was implementing between California and New Orleans. The T&NO grew to

become a major component of SP's operations in Texas, so much so that in 1920,

SP chose it to become the primary operating company into which other SP railroads in Texas and

Louisiana would be merged.

In 1890, the Lutcher & Moore Lumber Co. was

incorporated to own the Star & Crescent Mill and better organize the expanding

enterprise of the two owners. One component of the mill's operation was a logging tram running

north-northwest from the mill into the nearby forest. The distance and precise

route are unknown, but the main tram line was probably no more than ten miles

long. The tram's path north from the mill required a crossing of the T&NO's

tracks west of Orange, an area later platted as West Orange. The crossing was

uncontrolled; this was a decade before Texas law began mandating safety controls

at grade crossings of railroads. Trams and railroads had coexisted in

east Texas since the 1870s, and many more grade crossings would follow as trams and

railroads continued to penetrate the forests. The crossing at West Orange may

not have been the first such crossing of a lumber tram and a trunk line railroad

in Texas, but it was certainly one of the earliest.

By 1901, Lutcher and Moore had become unhappy with

the T&NO's service. Their mill was generating a substantial quantity of wood

products, but the T&NO was failing to supply enough railcars to satisfy demand

for outbound shipments. Lutcher and Moore believed the solution was to build a rail line thirty miles northwest from

Orange to Buna for a connection with the Gulf, Beaumont & Kansas City (GB&KC)

Railway. This was attractive because the GB&KC had recently been acquired by the

Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway. Access to Santa Fe's route

network would facilitate competition with the T&NO

for outbound shipments. A secondary objective was to access raw logs from forests farther north. With this strategy, the

Orange & Northwestern (O&NW) Railroad was chartered on January

14, 1901 to build from Orange to Buna. Lutcher & Moore's existing tram road to

the northwest out of Orange was upgraded to become the first several miles of

O&NW tracks. The thirty miles to Buna was completed in 1902. Several mills in

the Orange area and along the route to Buna were served by the O&NW.

|

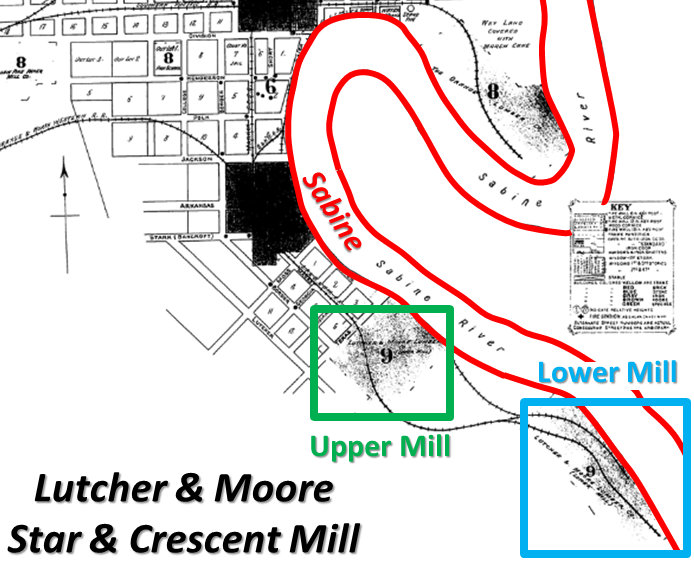

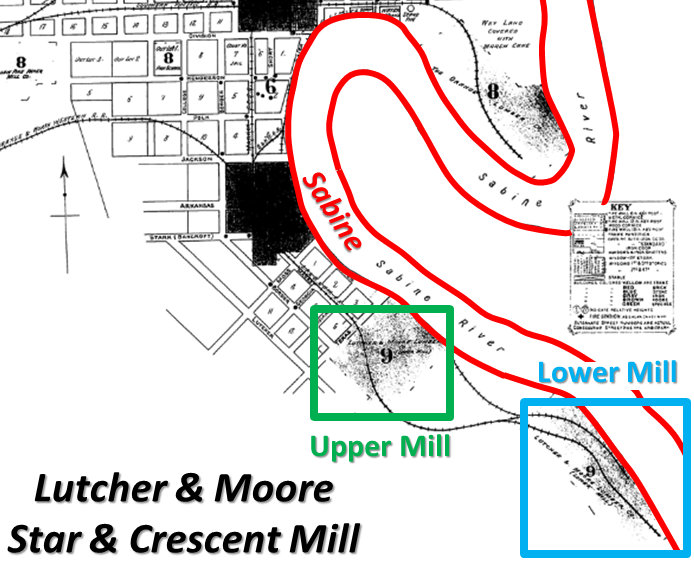

Left:

This annotated image from the index of the 1909 Sanborn Fire Insurance

Co. map set of Orange highlights Lutcher & Moore's Star and Crescent Mill

located along a horseshoe bend in the Sabine River on the south side of

Orange. The original mill became known as the "Upper Mill" in December, 1901 when

Lutcher & Moore acquired a competitor, the L. Miller Lumber & Shingle

Co., which they called the Lower Mill.

The Lower Mill had been

owned by Leopold Miller, a prominent local businessman who had moved to

Orange from Germany in 1881. Miller had opened a successful mercantile

business and had become involved in local banking, giving him the

resources to invest in a lumber mill. Soon after selling his mill to

Lutcher & Moore, Miller became the first President of the O&NW, and

both mills were served by its tracks. The Upper Mill was also served by the T&NO.

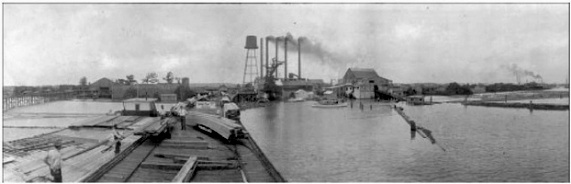

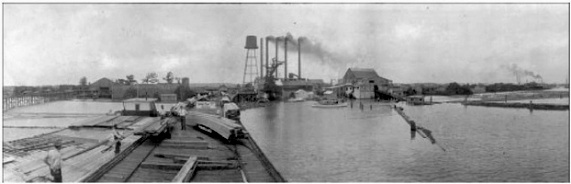

Below: This 1890 view of the Star and Crescent

Mill shows a pier with railcars adjacent to the Sabine River. Logs

floated down the river were

branded upstream so they could be identified to specific mills when

they reached Orange. (credit: Texas

Transportation Archive)

|

|

The construction to Buna

required crossing the Texarkana & Fort Smith (T&FS) Railway which had completed

its main line to Beaumont and

Port Arthur from

Texarkana in late 1897. About twenty miles south of

Texarkana, the T&FS tracks entered Louisiana and remained in state south to

DeQuincy, reentering Texas on an almost perfectly straight 47-mile track

running southwest to Beaumont. In 1900, the

Kansas City Southern (KCS) Railway was chartered in Missouri to

acquire various railroad assets out of foreclosure including the T&FS.

Since Texas law required railroads owning tracks in Texas to be headquartered in state, the T&FS

became the Texas-based subsidiary that owned KCS' tracks in Texas.

Where

the O&NW crossed the T&FS ten miles northwest of Orange, the new town of

Mauriceville was founded, named by O&NW President Leopold Miller for his

son, Maurice. Although KCS was a potential carrier for Lutcher and

Moore's mill products, a connection at Mauriceville could not supply

legitimate competition with SP for shipments out of Orange. From

Mauriceville, KCS went southwest to Beaumont and Port Arthur but no

farther whereas Beaumont was only a short distance west of Orange along

T&NO's tracks. Those tracks continued farther west to Houston, and its

parent railroad SP had tracks that continued west from Houston to San Antonio,

El Paso and California. To the north, SP and KCS both served

Shreveport. Although KCS did continue north to Kansas City, it was simply insufficient as a competitor to motivate changes to

SP's railcar allocations or pricing at Orange. Hence, the GB&KC

(Santa Fe)

connection at Buna remained the target.

Left: Since the "125" placard

is not present on the side of the building, this photo at Mauriceville was probably taken before

the Tower 125 interlocking was commissioned in May,

1929. (Mark St. Aubin collection) |

The founding of the O&NW as a means to facilitate trunk

line competition for SP was of significant interest to Benjamin Franklin Yoakum, a

pioneering Texas railroader who wanted to compete with SP across Texas and

Louisiana. Eighteen years after he started his railroading career at age twenty on an

International & Great Northern Railroad survey gang,

Yoakum became the General Manager of the St. Louis & San Francisco ("Frisco")

Railway in 1897. The Frisco was a major carrier in the Midwest and Plains

States, headquartered in St. Louis. By 1905, Yoakum was Chairman of the Executive Committee of the

Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad, a major Midwest railroad

based in Chicago. Yoakum was effectively Rock Island's Chief

Executive, and he was simultaneously the Chairman of the Board of the Frisco as he attempted to merge the two railroads.

Focusing on the Gulf Coast, Yoakum began to execute a plan to

accumulate and build out a set of railroads collectively known by the marketing

term Gulf Coast Lines (GCL) that would form a continuous route from

Brownsville to New Orleans via Houston.

The GCL was managed by Frisco executives but was owned by a financial syndicate

formed through the St. Louis Trust Co. For a portion of the GCL route from New

Orleans to Houston, Yoakum negotiated rights to use KCS' tracks between DeQuincy

and Beaumont. Since this segment included Mauriceville, Yoakum viewed the O&NW

as a potential source of feeder traffic to the GCL. He bought the O&NW in 1905,

adding it to the GCL and building connecting tracks at Mauriceville.

| The Tap Line Cases |

The founding of the O&NW was a classic example of a

tap line. A tap line was simply a chartered

and incorporated common carrier railroad owned by a

lumber company (or its closely related interests, e.g. management

investors) that moved logs inbound to the mill and wood products

outbound to interchanges with trunk line railroads, while also

serving the population along the route. Tap lines evolved west of the

Mississippi River. The West was larger and less populated, hence it had

longer, but fewer, roads for wagon transportation. With increased distances to move logs to

mills, timber companies found it more efficient to establish

remote camps for logging teams rather than move personnel to and from

the forest each day. This necessitated moving people and supplies by

tram to isolated outposts that might otherwise be inaccessible due to

the lack of roads. As

communities of laborers, their families and enterprising merchants

sprang up around the larger outposts, the tram lines serving these

outposts became essential for basic

transportation.

The western timber companies discovered a major benefit to

chartering and incorporating their private logging trams to become tap lines.

When common carrier railroads exchanged traffic, the revenue

for the entire shipment was split using a negotiated division

rate. As outbound wood products moved over a tap line to reach

connections with trunk line railroads, the tap line received a share of

the total revenue for the shipment, even if the movement was only a

short distance from the mill. This

produced additional income - allowances - to the tap

line's owners. Tap lines with

access to more than one trunk line had leverage to negotiate

higher divisions and allowances by favoring the higher-paying connection.

An allowance paid to a tap line from the shipping revenue on

the output of their owner's mills was, in essence, a "kickback" from the

trunk line, but it was legal. However, by

accepting the benefits of common carrier status, the tap lines

also accepted two significant legal obligations. They had to

offer transportation services to the public without

discrimination, and they had to set public tariffs

and charge fees for their services.

It seems obvious that a railroad would charge a fee for its service,

but logging trams owned by lumber companies had always hauled logs for

free; a tram was just

another component of the mill's operations. Private trams

were not common carriers, but tap lines were. If a tap line was undercharging (or not charging) their

mill to move inbound logs, then other nearby mills wanted the same rail

service at the same price, and therein lay the origin of a major dispute

heard by the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC). The ICC investigation

began in 1909 covering more than one hundred tap line railroads in

Texas, Arkansas, Louisiana and Mississippi. The ICC ruling, issued in

April and May, 1912, analyzed the details of each of the tap

lines and found that thirty of them did not qualify as common

carriers. In the ICC's view, the service each of these tap lines

was providing was a plant

service, an inherent part of processing raw timber into products, rather than a true transportation service.

Hence, they were not common carriers and therefore ineligible for

allowances. The ICC ruling forbid trunk

lines from making such payments to these tap lines.

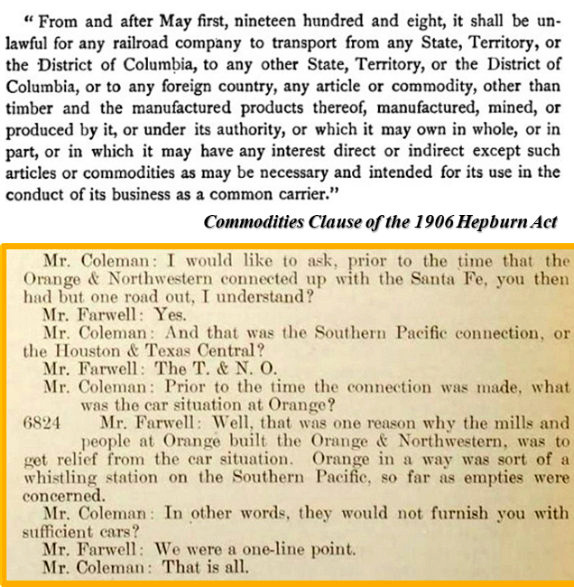

The

ICC ruling was appealed

to the U. S. Commerce Court, a Federal Court created

for the purpose of hearing appeals of opinions and orders issued by the ICC.

[The Commerce Court was short-lived, created by the

Mann-Elkins Act of June, 1910 and abolished by public law

in December, 1913.] The Commerce Court determined that the

ICC's

ruling against the thirty tap lines needed to be remanded to be

reevaluated under a proper reading of the law. The

ICC's legal analysis had concluded that tap lines converted from private logging trams

and still owned by their lumber companies failed to meet the

criteria for common carriers, regardless of any evidence

to the contrary. The Court ruled this to be legal error, pointing out that the

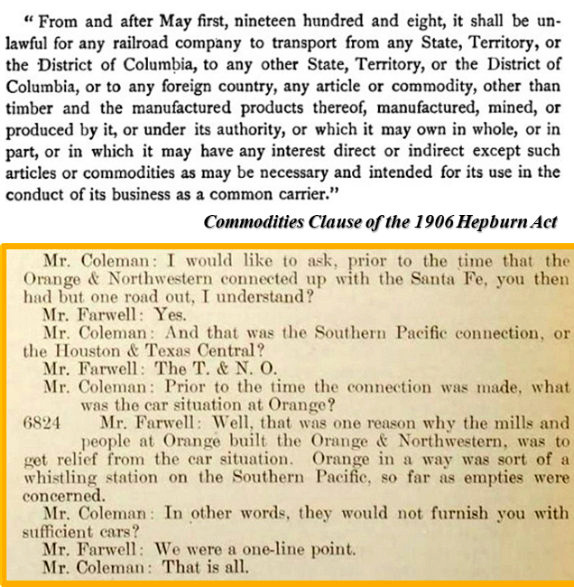

Commodities Clause of the Hepburn Act of 1906 (above

right) had specifically exempted "...timber and the

manufactured products thereof..." from the law's general

prohibition on railroads transporting products in which they had

any direct or indirect financial interest (items needed

by the railroad to function,

e.g. fuel, water, supplies, employees, etc. were also exempted.) The ruling of the

Commerce Court was appealed to the U. S. Supreme Court. The case

was heard in April, 1914 and the Supreme Court affirmed the Commerce

Court ruling in its entirety in an opinion issued the following month.

Below Right: The ICC ruling did not affect

the O&NW; it was an undisputed common carrier trunk line, part of the GCL since 1905.

But O&NW management did appear as

witnesses, called to testify before the ICC at various hearings. In this example,

ICC Examiner Coleman questioned Mr. Farwell, an O&NW executive. |

By early 1906,

Yoakum had extended the O&NW 28 miles north from Buna to Newton, a small community deep in the forest

near the Louisiana border. The extension appears to have served two purposes.

The forests between Orange and Buna were beginning to thin out, hence

the extension reached additional timber needed by the mills at Orange. And

since Santa Fe's tracks at Buna continued north to Kirbyville, Jasper and

beyond, there were few remaining towns of any size within a reasonable distance

of the GCL at Mauriceville that did not already have rail service. Newton was

the exception, having had a Post Office since 1853 and a private college since

1889. It was the county seat at the geographic center of Newton

County which had over 7,000 residents in the Census of 1900. Presumably, Yoakum saw Newton and the surrounding county as ripe for population

growth and increased commerce that the O&NW would stimulate.

|

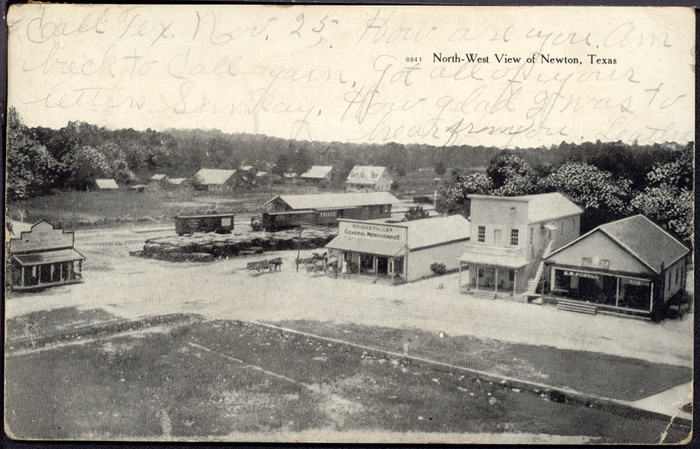

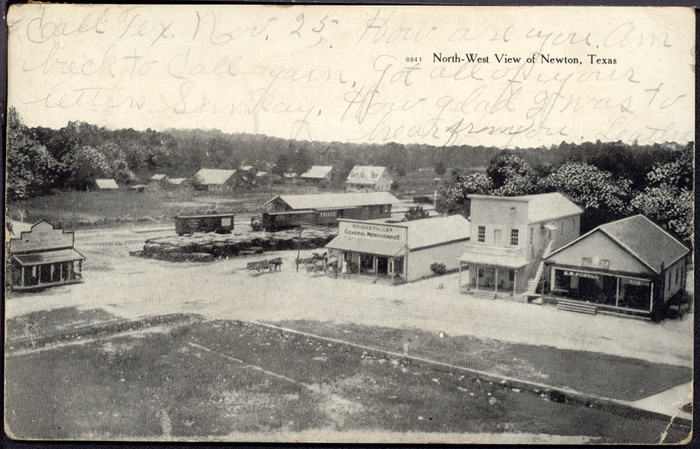

Left:

This 1907 view of Newton is a post card (Curt Teich & Co., Chicago) from the Murry

Hammond collection, courtesy of the Texas Transportation Archives.

Consistent with Yoakum's acquisition of the O&NW, a Frisco boxcar can be

seen directly adjacent to the O&NW depot in the background.

Right: This 1913 map from the Louisiana Railroad

Commission (with green and red ink lines hand-marked for an unknown purpose)

shows the O&NW route between Orange and Buna with various locations

identified. Near the Sabine River, the southern part of the Orange, Call

& Pine Belt (OC&PB) private tram is also shown. Despite its appearance

on a 1913 map, this narrow gauge tram operated in 1898-99 and not much

beyond that, so far as is known. |

The tram database of the

Texas Forestry Museum includes this

personal recollection of the O&NW:

W. E. Merrem, a Houston Oil

Company executive, remembered that the road “was in bad shape. I rode it a

number of times before we had automobiles and decent roads. It was really

something to ride. They had no ballast on the roadbed, and it was so dusty you

couldn't see from one end of the car to the other. It mostly handled sawmill

products, which they picked up at Newton.”

|

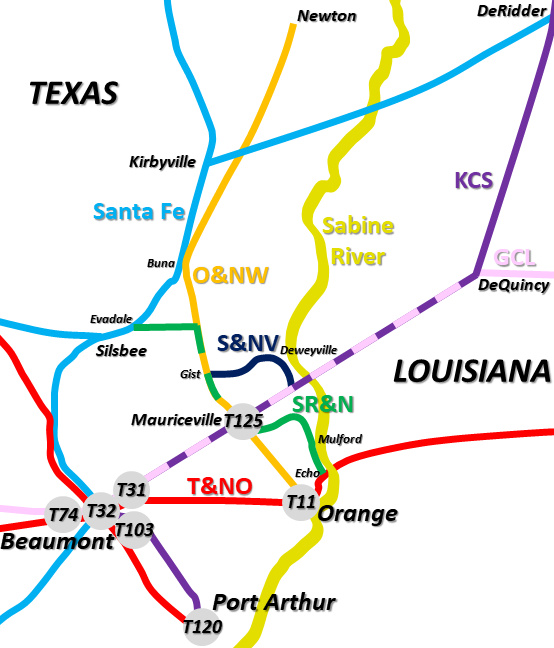

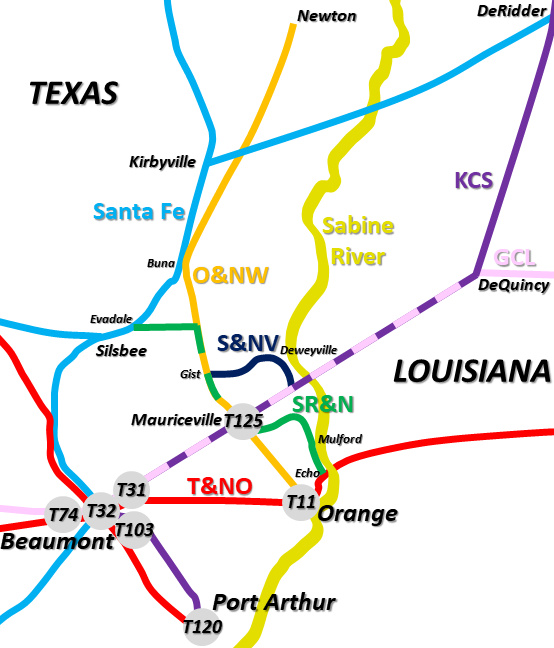

Left:

Historic rail lines in the vicinity of Orange are shown on this

map, but for no particular date.

Only three track segments on the map are currently abandoned: the

T&NO northwest of Beaumont, the entire Sabine and Neches

Valley (S&NV), and the O&NW north of Buna (to Newton.) The Santa

Fe line southwest from Beaumont becomes abandoned about ten miles out of town.

Although 49 miles

of former O&NW tracks north from Mauriceville to Newton was

abandoned in 1963 by Missouri Pacific (MP), successor to the GCL, the

right-of-way (ROW) between Mauriceville and Buna was acquired shortly

thereafter by the Sabine River & Northern (SR&N) Railroad. The

SR&N had begun a construction project to serve paper mills at Mulford and Mauriceville. The track to Mulford was

built by SR&N in 1966, five miles north from the T&NO at

Echo.

In 1967, track-laying continued north and west from Mulford to

Mauriceville, along with new tracks laid to Buna

on the purchased ROW. In 1990, the SR&N opened an 8-mile line

west to Evadale from a new junction on its existing track eleven

miles north of Mauriceville.

The SR&N is owned by

Temple-Inland, a packaging and building products company traditionally

based in Diboll, Texas that became a

wholly-owned subsidiary of International Paper in 2012. The SR&N functions like the

classic "tap line" railroads of the early 1900s, i.e. a common

carrier railroad founded by a wood products company used for moving raw

materials to mills and finished products to trunk line interchanges. For the SR&N, these interchanges are at

Evadale, Mauriceville and Echo.

The S&NV was

chartered in 1921 as a tap line for the Peavy-Moore Lumber Co. which had

a sawmill at Deweyville. The S&NV had connections to the KCS south of

Deweyville and a connection to the O&NW at Gist. The sawmill burned in

1944 and the S&NV was abandoned the following year.

Only KCS and the

SR&N still operate under the names shown on the map. The T&NO and the GCL lines,

including the O&NW line south of Mauriceville,

are now part of Union Pacific (UP). The Santa Fe lines are now

part of Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) except the line

between Kirbyville and DeRidder operated by the Timber Rock Railroad.

The interlockers in this area identified by tower number were at

Beaumont (Towers

31, 32,

74 and 103),

Port Arthur (Tower 120),

Mauriceville (Tower 125) and West Orange (Tower 11.) |

Texas law requiring interlockers or gates for safety

purposes at grade crossings of different railroads took effect in 1901. Soon,

the Railroad Commission of Texas (RCT) began issuing orders prioritizing the

crossings to be interlocked and the procedures for obtaining final approval for

each interlocking plant installation. Low on the priority list (or more

precisely, "not even on the list") was the issue of how to handle the many

crossings throughout east Texas where a lumber tram crossed a trunk line railroad. Such crossings had existed for

years and the railroads had accommodated them without issue since they were a

necessary part of east Texas lumbering, an industry that provided profitable

business to the railroads. Some lumber trams brought logs to a siding for a railroad to haul

to the sawmill, but the larger lumber companies had vast networks of tram lines

and they sometimes needed to cross a railroad for no other purpose than to

simply get to the other side.

Were these crossings somehow exempt from the

interlocker law since they involved a tram instead of two common carrier

railroads? It would take many years for RCT to sort out the

answer, yet the safety issue was no different. To the extent there was any

attempt by RCT to begin enforcing interlocker requirements for tram crossings,

it appears to have begun with Tower 110 at Dayton

in 1917 and Tower 111 at Trinity in 1919. In the

1920s, a few additional east Texas locations were interlocked:

Hyatt, Devers,

Cruse,

Fullerton, along with two trunk line crossings by the Grogan-Cochran Lumber Co. near

Magnolia in the 1930s. Like other such crossings, the tram that ran

northwest from the Star & Crescent Mill was not interlocked where it crossed the

T&NO in West Orange. Yet, when the tram morphed into the O&NW in 1901, it became

one of the first crossings to be interlocked as a result of the new law that

took effect that same year.

|

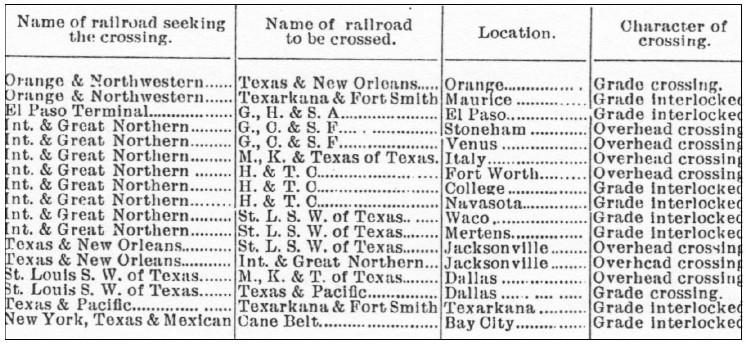

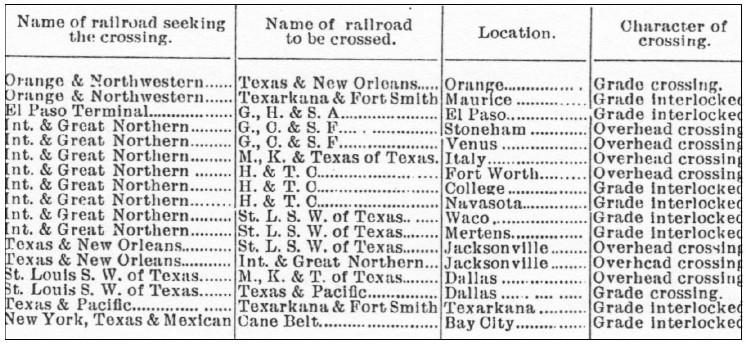

Left: RCT's 1903 Annual Report (covering the 1902

calendar year) included a table of priority crossings to be addressed.

It did not list the five interlockers approved in 1902; all subsequent

reports listed all active interlockers by tower number plus those "Under

construction." The first two entries in this table were for the O&NW

crossings at Orange and "Maurice".

The first

column identifies the railroad seeking

the crossing, a detail omitted from all subsequent reports. It appears

that the "seeking" railroad was not simply the second railroad at a

crossing because the entry for Texarkana conflicts with that rule. The

difference in the Character of crossing

between "Grade crossing" and "Grade interlocked" is undetermined; none

of these crossings were interlocked at the time. It is also unknown

whether the "seeking" railroads had actually made a request to RCT for

interlockers at the reported locations; it seems doubtful so soon after

the 1901 law took effect. Note that the law also required RCT

approval for grade-separated "Overhead crossings". The

composition of this table is also confusing because some

interlockers were approved quickly in 1903, e.g.

Waco, "College",

Navasota

and Orange, while others were delayed for many years, e.g.

Mertens (c.1935) and "Maurice" (1929). |

RCT commissioned Tower 11 for operation at the T&NO / O&NW

crossing at West Orange on June 27, 1903. It housed a 12-function mechanical

interlocker,

the minimum for a basic crossing consisting of a distant signal, a home signal

and a derail in each of the four directions. RCT documentation states that the

Tower 11 interlocker was installed by the T&NO but does not identify which

manufacturer built the plant. A table published by RCT in 1907 lists an average

of 21 movements per day past Tower 11 for the twelve months ending June 30,

1906. Although no photos of Tower 11 have surfaced, it is known to have been a

manned tower (as opposed to a cabin interlocker) because "Train Order Office Hours" of 7:00 AM to 11:00 PM were

published for Tower 11 in a 1920 SP timetable. Tower 11 was almost certainly a 2-story

tower similar to other SP towers in Texas, e.g. Tower

31 located twenty miles west near Beaumont.

Through the end of 1929, Tower 11 continued to be listed

in RCT documentation as a 12-function mechanical interlocker, but RCT's final

published comprehensive interlocker list dated December 31, 1930 reported Tower 11 as an

8-function automatic interlocker. A letter in the RCT archives at

DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University, issued by SP on June 29, 1931

notified RCT that the conversion of Tower 11 to an automatic interlocker had finally been

completed. That this fact somehow was reported in a table dated December 31,

1930 is a bit problematic. There are two additional 1931 dates in this table

(for Lubbock and Plainview)

which may indicate that the table was published later in the year, or perhaps

the table was complied to anticipate the completion of authorized work.

The conversion of Tower 11 to an automatic plant coincided with the end of operations at the

Star & Crescent Mill, which closed in 1930. O&NW

movements pasts the tower would be reduced since it was no longer carrying

inbound logs nor outbound wood products for the Star & Crescent Mill, but the line remained operational by MP

and continued to serve other mills. The reduction to eight functions undoubtedly reflects elimination of the derails.

In an order issued May 1, 1930 for Tower 142 in

Plainview, RCT stated that "...derails have caused as many or more

accidents as they have prevented and the elimination of same from interlocking

plants of all kinds has been recommended for the past several years by the

American Railway Association...". Interlockers installed

after May, 1930 were not likely to have had derails.

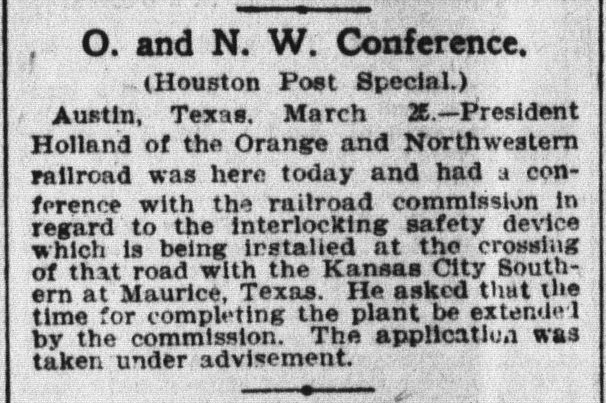

Right: The

Houston Post of March 26, 1904 reported on a meeting the

President of the O&NW attended at RCT headquarters in Austin. As noted

above, RCT's Annual Report published at the end of 1902 included a table

of priority locations for interlocker installations which included the

two O&NW crossings, at Orange and "Maurice." The details of the meeting

are unreported, but the O&NW apparently

obtained permission for additional time to install an interlocker at

Maurice.

It does not seem unusual that the O&NW was

successful in obtaining permission from RCT to delay the installation of

the Mauriceville interlocker. That the delay lasted twenty-five years

does seem odd! To add to the mystery, the fact that the Mauriceville

interlocker was number 125 suggests that the proposal to initiate

engineering design and installation of the interlocker was not submitted

to RCT until the latter months of 1925. This is deduced from the fact

that a tower number was assigned by RCT when the initial interlocker

application was made. Towers 124 and 126, both in

south Fort Worth, were installed in the

latter half of 1926, and a typical implementation schedule was eight to

twelve months. Stranger still, Tower 125 was commissioned on May 2, 1929,

nearly three years after Tower 126 became operational in June, 1926.

Based on the March, 1904 meeting in Austin and allowing a year of delay

and another year to propose, build and install a Mauriceville

interlocker, it should have been commissioned around April, 1906, not May, 1929. The reason for this enormous cumulative delay

is undetermined. It should be noted, however, that the 1929 date can be

traced to MP's efforts. MP and its subsidiaries had fifteen interlockers

commissioned by RCT in 1929 at rural locations, undoubtedly the result

of a corporate directive. |

|

Tower 125 was listed by RCT as a 10-function mechanical

cabin interlocker. In general, cabin interlockers were so named because the

plant and its controls were housed in a small, trackside hut ("cabin") with a

locked door. The controls were operated by crewmembers from trains on the less

busy line, with the signals otherwise set for unrestricted movements on the

busier track at all times. Photographic evidence (see top of page) indicates

that the Tower 125 interlocker and its controls were installed inside the

Mauriceville depot rather than in a trackside cabin. Rather than the

traditional twelve functions of a minimum standard interlocker, cabin

interlockers typically had fewer functions because the two distant signals on the less busy line, in this case

the O&NW, were omitted. There was no need

for a distant signal to

warn O&NW trains to stop at the crossing because all

O&NW trains were required to stop at the crossing. A fixed sign at the appropriate distance in

each direction provided sufficient notice to

O&NW locomotive crews that they were approaching the crossing and needed to stop so that the signals could be set

by hand to allow them to cross the KCS tracks. [At Mauriceville, a depot employee

most likely lined the signals for O&NW trains

rather than a crewmember.] After a suitable safety delay enforced by the

interlocker, lining the O&NW home signal to grant a PROCEED condition would automatically issue a

STOP indication on the home and distant signals on the KCS

tracks and set the derails. The signals and derails would be reversed manually once the O&NW train had completely crossed

the diamond. Derails were still required because Tower 125's commissioning was a

year prior to RCT's Plainview order.

|

Left: The

Tower 11 interlocker made front page news in the

Orange Daily Tribune of

Friday afternoon, October 16, 1903 by derailing a locomotive, thereby

fulfilling its safety mission. The mention of a "special train"

along with a

headline indicating the interlocker was being "Tested by a Party of

Southern Pacific Officials" suggests that the train was

intentionally testing the derail. It is unsurprising that such

tests might have occurred in the early days of Texas interlockers and

they were apparently worthy of Page One news, at least in a town the

size of Orange.

Below:

A Google Earth view from 2019 shows the O&NW ROW still in use

north of the Tower 11 crossing. To the south, 0.75 miles of track

was abandoned in 2000 eliminating the diamond. Historic aerial imagery

and topographic maps indicate that the apparent ROW southwest of the crossing

was originally a levee but later (post-1959) had rails that remained

visible as late as 1983. The ownership and purpose of those rails is undetermined.

|

|

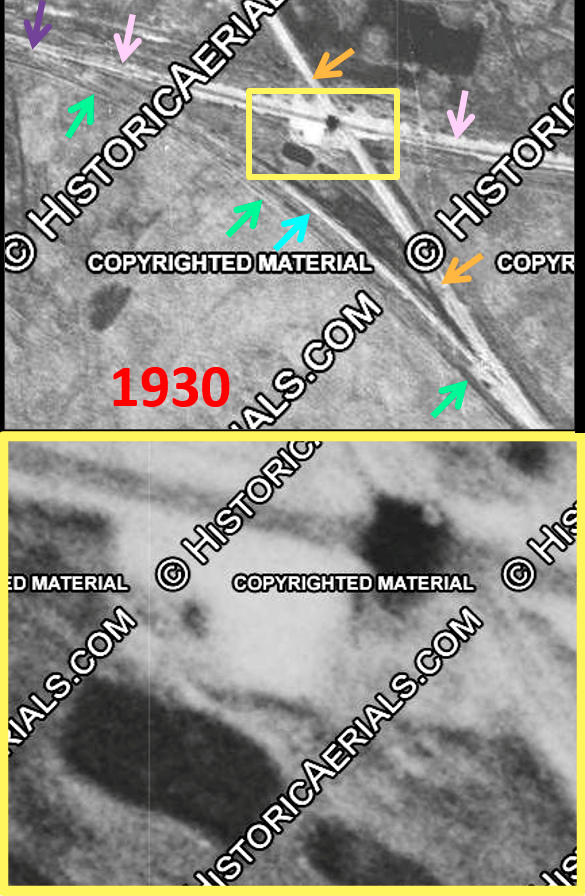

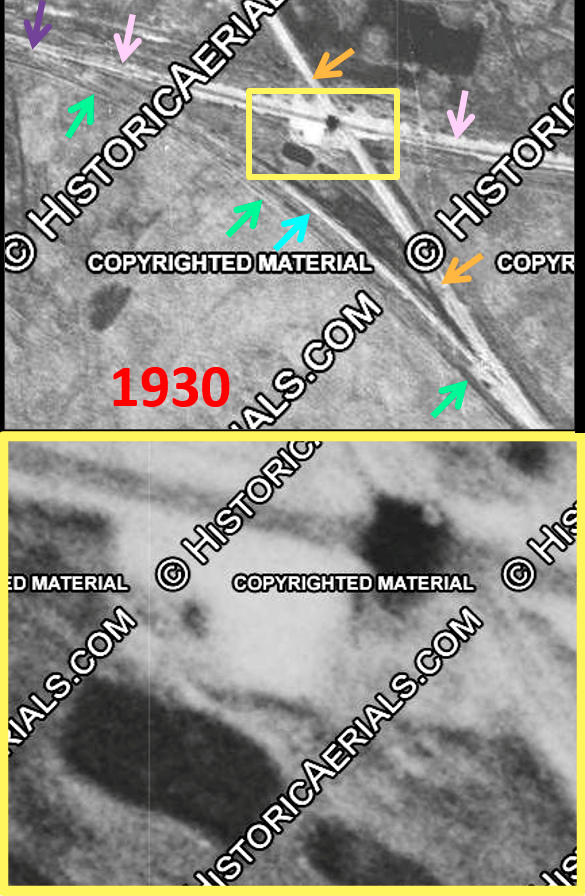

Left: This

1930 aerial image ((c) historicaerials.com) of the Tower 11 crossing is

difficult to interpret due to the lack of resolution. The O&NW (orange

arrows) [by this time, owned by MP] and the T&NO (pink arrows) cross within

the yellow rectangle, but what to make of the magnified scene of the

crossing (lower image)? Telltale shadows combine to produce a vague

outline of what appears to be a structure with a white roof possibly

having an angled wall on the southwest side, or more likely an overall L-shaped

structure. What appears to be a small dark shadow covers the crossing

diamond, but the shadow does not have a clean, rectangular shape.

Instead, it looks as if it might be cast by some sort of uneven

structure atop the northeast corner of the building -- if it is a

building.

Was this some kind of tower facility that had been

integrated into a building? The outline of the building -- if it is one

-- could resemble an L-shaped depot or railroad office. There could have been a West Orange

depot at the crossing, but there is no mention of one in T&NO

timetables. A 1918 T&NO Employee Timetable (ETT) has a milepost entry

for the O&NW crossing, but the nearest depot is more than two miles

distant in either direction. And what to make of the dark rectangle

beside the building. It doesn't look like a shadow, perhaps a pit or a

stack of dark material, but it has a similarly "shaded but less dark"

path leading back to the O&NW right-of-way. Perhaps this was a roadway

for workers to reach the facilities?

Elsewhere, a curved linear

area (blue arrow) appears to connect back to the O&NW tracks and

possibly has a connection to the T&NO at the other end (purple arrow.)

The lack of image detail makes this speculation at best. A second curved linear area (green arrows) looks

more like a levee. Although it appears track-like in places, it does not

seem to have a clear connection to the known main line tracks at either

end. The next available aerial imagery is from the 1950s, by which time

all of this detail has disappeared and nothing obvious is visible except

the levee -- if it is one. |

|

Left: This recent annotated Google Earth image shows the location of the

Tower 11 crossing in West Orange where the former O&NW line continued

northwest toward Mauriceville. The former T&NO line runs mostly horizontal

across the image from west (toward Beaumont) to east (toward New Orleans). The

Lutcher & Moore mill site was farther east at the bend in the Sabine. RCT

drawings on file at DeGolyer Library at SMU indicate that Tower 11 was located

on the southwest side of the crossing. As the 1930 imagery shows, there was

definitely something in that quadrant. |

|

Left: This Google

Earth image shows the Tower 125 crossing at Mauriceville. North of

there, MP abandoned the tracks to Buna and beyond in 1963. The

SR&N bought the abandoned ROW and laid new tracks to Buna in 1967, the

year after construction of its line from Echo had begun. The Tower 125

interlocker was located in the depot on the north side of the crossing.

A 1956 KCS employee timetable listed the Mauriceville crossing as

"Interlocked" but did not include "(Automatic)" as it did for some of

the other crossings listed. It's likely that the crossing was converted to an automatic interlocker by the mid-1960s. A connecting

track in the

southern quadrant probably existed in the Yoakum era, and it appears on imagery

from 1930 until it was removed between 1996 and 2004. Similarly, a

connecting track in the eastern quadrant that probably dated to the

Yoakum era is visible on imagery from 1930 to 2018, but is not present

on 2020 imagery. |

Above: Looking

south-southeast, the Mauriceville depot fronted the north side of the

KCS tracks, between the diamond and the trailer.

Above: FM 1130 crosses

the SR&N and runs behind the former depot site. (Google Street View images, June

2015)

|

Right: This bird's eye view of the Tower 11 crossing

from c.2005 shows substantially disturbed earth, perhaps in preparation for the

additional track that UP added through this junction. Compare this view with the

satellite view from 2019 farther above. The tower was located approximately

where the utility pole sits southwest of the crossing. The location remains to

be field-checked for evidence of the tower's foundation, but the chances are

slim since it was removed nearly a century ago. |

|

|

Right: Looking southeast from Tulane Rd. along the former

O&NW ROW, UP's tracks now curve to the east instead of crossing over at Tower 11

as they reach the main track, which is occupied by a UP train. |

|