Texas Railroad History - Tower 19 - Dallas

Crossing of the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe Railway

and the Missouri, Kansas & Texas Railway

Above: From the rear platform

of his business car, railroad executive John W. Barriger III took this photo

facing northwest toward downtown Dallas sometime between the mid 1930s and the

early 1940s. Barriger's train is headed south on tracks of the

Missouri - Kansas - Texas (MKT) Railroad. His business car has just crossed Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe

(GC&SF)

Railway tracks

that angled northeast across Dallas south of downtown. Tower 19 -- here seen trackside to

the right -- sat in the north quadrant of this X-pattern crossing. The tower

Barriger saw was not the first iteration of Tower 19. Railroad Commission of Texas

(RCT) documentation archived

at DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University, includes a map dated

November 6, 1908 showing Tower 19 in the south quadrant of the diamond,

presumably its original location upon commissioning in July, 1903. Another map dated November 19, 1921 shows the tower in the north quadrant.

Tower 19 was a "Santa Fe tower", i.e. designed, built and staffed by GC&SF

personnel, although capital and recurring expenses were shared with MKT and

eventually with other railroads. It resembles other Santa Fe towers for which

photos exist, e.g. Tower 57, which opened about 1.5

miles north of Tower 19 in November, 1904. In the early 1990s, a detailed study

conducted by the Historic American Building Survey (HABS) as part of the

Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) reported 1924 as the date of Tower

19's construction, but the source for that date has not been determined. If it

is accurate, then the most likely scenario is that sometime between 1908 and

1915, the GC&SF moved the original tower diagonally across the diamond.

Relocating the tower out of the south quadrant would clear real estate for new

Union Terminal Co. tracks that would connect to the Santa Fe tracks at Tower 19.

Union Terminal was building the new Dallas Union Station, which opened less than

two miles north of Tower 19 in October, 1916. Union Terminal tracks are shown

near Tower 19 on a 1915 MKT track chart but they do not appear in Barriger's

photo, likely replaced in 1920 by a second main line parallel to MKT's tracks.

After relocation of the original tower in 1921 (or earlier), a new tower was

built in 1924, also on the north side of the diamond, mounted on the large

concrete pedestal visible in Barriger's photo.

The other possibility is

that the 1924 construction date reported by HABS is simply wrong, and a new

tower had been built in the north quadrant by 1921 and perhaps by 1916.

Unfortunately, the MKT track chart from 1915 does not show any of the three towers

(10, 19 and 57) that could have been marked, and oddly, no mention of any Tower

19 reconstruction has been noted thus far in reviews of the files at DeGolyer

Library. If the north quadrant tower on the 1921 map was a new tower, it was

constructed sometime after 1908, a maximum span of thirteen years. This would

tend to make it less likely that Tower 19 was rebuilt again in 1924. However,

the massive 1922 flood on the Trinity (before the levees were built) might have

justified a 1924 rebuild even if the 1921 tower was a relatively new structure.

Regardless, the tower that Barriger photographed was the final version of Tower

19 and it is preserved at the

Museum of the American Railroad in Frisco, Texas (photo

below, from Google Street

View, September, 2018.) It sat on a concrete pedestal for flood protection -- it

was only a half mile from the main channel of the Trinity River, well within the

flood plain. The original tower had likely suffered substantial damage from the massive flood of May, 1908

(Tower 57 was described as "under water"), which surely influenced the

decision-making over Tower 19's relocation and/or rebuild. The pedestal has been recreated at the

Museum to elevate

the tower to its operational height. The original 1903 tower might have been

elevated to some extent, just for drainage purposes -- note the low lying area

diagonally across from the tower in Barriger's photo -- but it is doubtful that

it was

enough to mitigate damage from the 1908 flood.

By the early 1870s, Dallas had become a two-railroad

city. The east/west Texas & Pacific (T&P) crossed the north/south Houston &

Texas Central (H&TC) at the east end of downtown, and investors had begun to look at building rails in additional directions.

Cleburne, about fifty miles southwest, was viewed as a prime opportunity. It

had become the seat

of Johnson County a few years earlier and was experiencing rapid population growth.

After a chartered narrow-gauge railroad had twice failed to attract enough investment

to initiate construction, a new charter was issued

in September, 1880 for a standard

gauge rail line to Cleburne to be known as the

Chicago, Texas & Mexican Central Railway Co. (CT&MC). The CT&MC construction

began at Dallas in 1881, the goal being a connection at Cleburne with the Gulf, Colorado

& Santa Fe (GC&SF) Railway. The GC&SF tracks had reached Cleburne only two

months earlier as part of a main line being built from Temple to

Fort Worth. When area newspapers celebrated the

first CT&MC train from Dallas in January, 1882, the railroad was already facing

bankruptcy. Its financial condition quickly became public as contractors gave

stories to the newspapers about the CT&MC's failure to pay its bills. Despite negative cash flow and

significant debt, its rail line from Cleburne to Dallas was valuable, as was its

right to build farther northeast from Dallas to Paris,

a feature incorporated into the charter ostensibly to support building north

toward Chicago. Rumors began to spread

that the GC&SF would rescue the CT&MC simply to acquire the tracks to Dallas. The Fort Worth Daily Democrat of

March 3, 1882 reported "...that the company proposes to clear

the road of debt, and that negotiations on that basis are going on with the

Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe for the Chicago, Texas and Mexican Central."

The GC&SF proceeded to buy the CT&MC on August 1, 1882 and assume its debt.

That same day, August 1, 1882, rail baron Jay Gould bought the Galveston,

Houston & Henderson (GH&H) Railroad. The GH&H owned a bridge from

Galveston Island to the mainland at

Virginia Point, and tracks from there to

Houston. It was a small railroad, but its access

to Galveston -- Texas' largest city -- was important because Gould wanted to

export Midwest agricultural and industrial products through the Port of

Galveston. Gould had been assembling a collection of

lines from the Midwest to

Houston under his Missouri Pacific (MP)

Railroad (where he had a large ownership position.) His objective was for MP to control the entire haul

from St. Louis and Kansas City to Galveston; the GH&H was the

final piece of the puzzle.

Earlier, Gould had initiated takeovers of various

Texas

railroads to provide the intermediate routes. One of these was the Missouri, Kansas & Texas (MK&T, "Katy")

Railway, which had built south from Missouri and Kansas through Indian Territory

and completed a bridge over the Red River into Denison in late

1872. (By the time of Barriger's photo above, the railroad's name had changed to

the Missouri - Kansas - Texas Railway as a result of a corporate reorganization

during its emergence from bankruptcy in 1923 -- but everyone just called it the

Katy.) Gould immediately saw the value of the bridge at Denison, so in 1873, he initiated a long term plan to take control of the Katy by getting

his henchmen hired into Katy's executive management. Though it took six years,

in

December, 1879 they had accumulated sufficient power to orchestrate Gould's election

as President of the

Katy.

|

Gould was the Katy's President, but he had little ownership in the

company -- the Katy's stock was so diluted that there were few large

blocks of stock available for private sale. To

bolster his control, Gould leased the Katy in December, 1880 to

MP. He then initiated an expansion deep into Texas with new construction and

takeovers of existing railroads. MP was the public face of the Texas

construction but the work was legally conducted under the Katy name; MP did not have a charter to build railroads in Texas.

One of the new Katy lines was from Greenville to

Mineola, to which an International & Great

Northern (I&GN) branch line had been built years earlier. The Katy

already had a Denison - Greenville line, and Gould had his sights on the I&GN; its branch led to a main line

route to Houston, thus facilitating Denison - Houston service via

Mineola.

Gould next pursued the T&P. Its construction from

Texarkana to El Paso had stopped in

Ft. Worth due to financial difficulties. Gould offered to build the

remainder of the line in exchange for T&P stocks and bonds conveyed to

him on a "per-mile" basis. As he built westward, he soon accumulated

a controlling interest, ratified by T&P shareholders in April, 1881. Gould

promptly leased the T&P to MP. He then

turned to the I&GN, the largest railroad in Texas. Via Longview, the T&P and

the I&GN would

provide a Texarkana to Houston haul, and MP already controlled tracks

from St. Louis to Texarkana. Via Denison and Mineola, the Katy and I&GN would

have rails from Missouri and Kansas all the way to Houston, to which the Katy

was also building via Ft. Worth

and Waco. Gould was able to pressure I&GN

management to agree to a stock swap for Katy securities in June, 1881,

giving the Katy ownership of the I&GN.

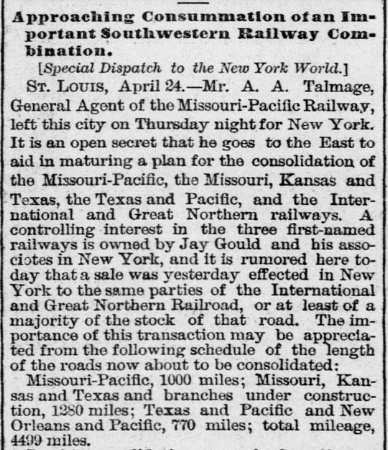

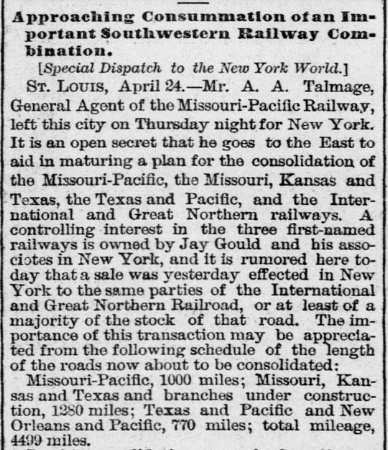

Left: Even before the

I&GN deal was sealed, the Galveston

Daily News of April 30, 1881 carried this dispatch from St.

Louis speculating on a consolidation plan for Gould's Texas railroads

into MP.

Gould's

Texas railroads remained legally separate despite being effectively

controlled by MP.

Gould needed to maintain them as such because they had

charter authorizations to build and operate rail lines in Texas,

something MP did not have. MP would have no hope of getting its own

Texas charter passed into law -- the Legislature would face too much

public opposition stirred up by rival Texas railroads. As a result of

accounting and operating policies tilted heavily toward MP, its

stockholders (particularly Gould) would reap the benefits of the

combined enterprise, to the substantial detriment of the stockholders of

the Katy. |

By the fall of 1882, the GC&SF was rightfully alarmed

by Gould's moves. Unless it could find a partner to

stimulate traffic with out-of-state markets, it was destined to become

subservient to the bigger railroads in Texas, of which the Gould amalgamation was

the largest. In 1886, the GC&SF agreed to be acquired by the Atchison, Topeka &

Santa Fe (AT&SF) Railway, a larger, high plains and southwestern railroad

ranging from Kansas to California. There had been rumors that the GC&SF's goal

in acquiring the CT&MC in 1882 was to "out-flank" Gould by building a line to

Paris to meet the St. Louis - San Francisco ("Frisco") Railroad which was

building south from Missouri. A connection at Paris would produce a faster route

from St. Louis to most Texas destinations compared to Gould's routes via

Texarkana or Denison. The line to Paris was built by the GC&SF in 1886 as part of

its acquisition by the AT&SF.

In November, 1886, a new Texas Attorney General, James S.

Hogg, was elected on a campaign to go after the railroads for various

infractions of state law and violations of their charters. Hogg wasted no time

in filing lawsuits, particularly against the I&GN and the Katy. When all of the legal dust

settled several years later, Gould was no longer President of the Katy -- he'd

been fired by its stockholders, MP's lease of the Katy had been revoked, and the

Katy's expansion into Texas had been declared unlawful by the Texas

Supreme Court. State law in 1870 had granted the Katy permission to use

its Kansas charter as the basis for crossing into Denison over its

planned Red River bridge, but under Gould's control, the Katy had begun

to expand southward toward Houston (which Gould argued was permissible

since building to "the Rio Grande" was mentioned in the Kansas charter.)

As the Katy had neither

a Texas headquarters (a state law requirement) nor a Texas charter, the court ruled the expansion illegal. To clean up

the Katy's mess in the aftermath of the litigation, a new Texas charter for

the Katy was filed on October 28, 1891

and approved by the Legislature establishing the Missouri, Kansas & Texas

Railway Co. of Texas, to be headquartered at Denison as a wholly-owned

subsidiary of the parent Katy corporation. The Katy was forced to sell the I&GN

back to Gould; the Legislature was simply unwilling to grant the charter if the

Katy owned the I&GN.

Under Gould, the Katy had frequently arranged

for independent investor groups to charter and build branch lines that

would later be acquired and merged into the Katy. One such line was the

Dallas & Waco Railroad, sponsored by the Katy for the purpose of

building between Dallas and Hillsboro. The Katy already served Hillsboro

on its main line south from Ft. Worth, and the Katy served Dallas with a

line from Denison via Greenville. It also had a branch to Dallas from

Denton, a town on the Whitesboro - Ft. Worth joint line shared with the

T&P. Dallas was becoming too important to be a dead end for the Katy,

hence the decision was made to build south from Dallas to reach the main

line out of Ft. Worth at Hillsboro. The overall goal was to continue

pushing south and east toward Houston. Despite the Katy's on-going

litigation in various courts, the Dallas - Hillsboro line was completed

in 1890 and its operations were absorbed into the Katy in 1891 under the

new charter. The Dallas - Hillsboro line crossed the Santa Fe tracks

south of downtown

Dallas, the future site of Tower 19.

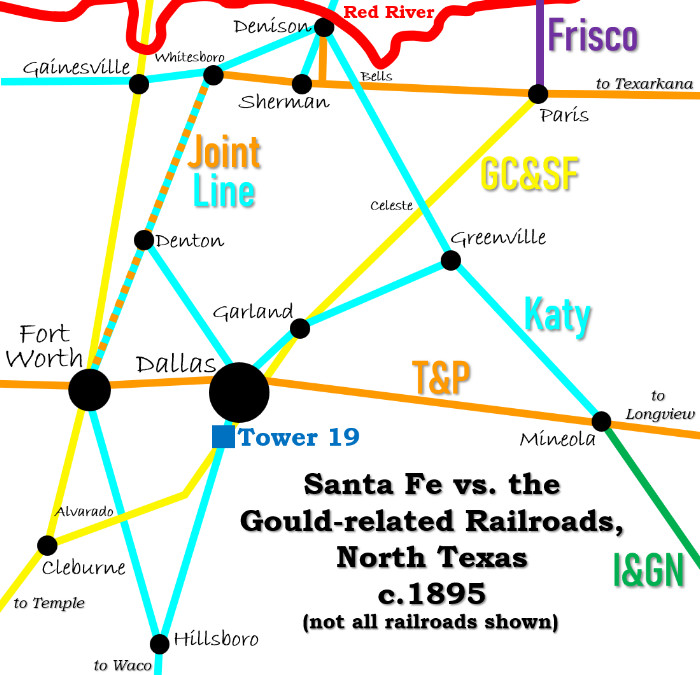

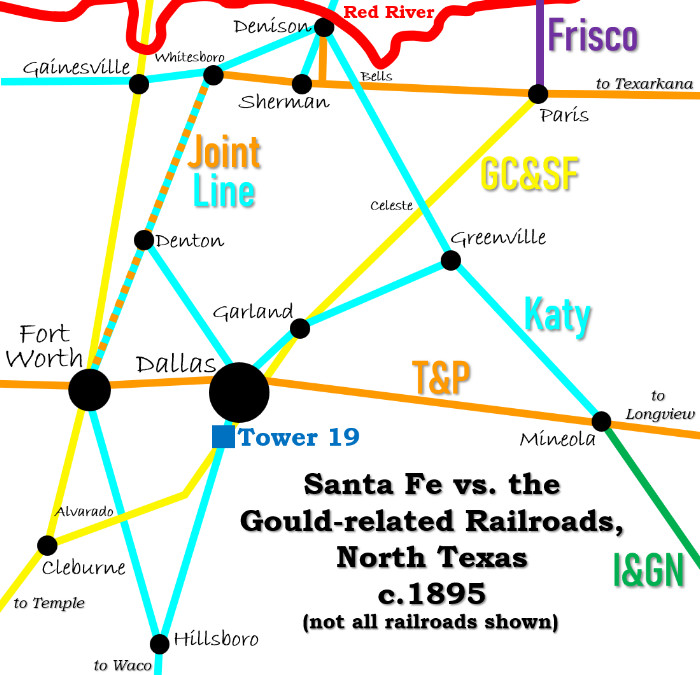

Right: The Frisco's line to Paris in 1888

enabled Santa Fe to counter Gould's domination of Midwest

traffic. The Katy returned to independence with a Texas charter in 1891,

but Gould maintained control of the I&GN and the T&P. Jay Gould died in late 1892 and was

succeeded by his son George as President of both railroads. |

|

|

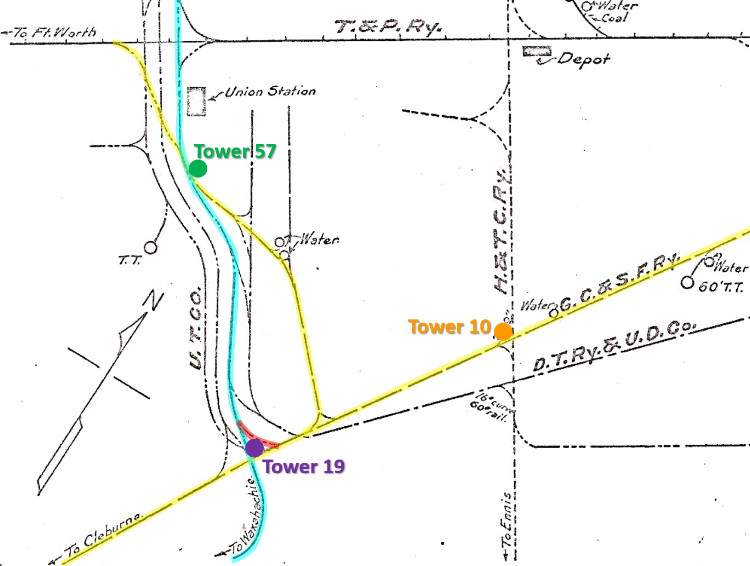

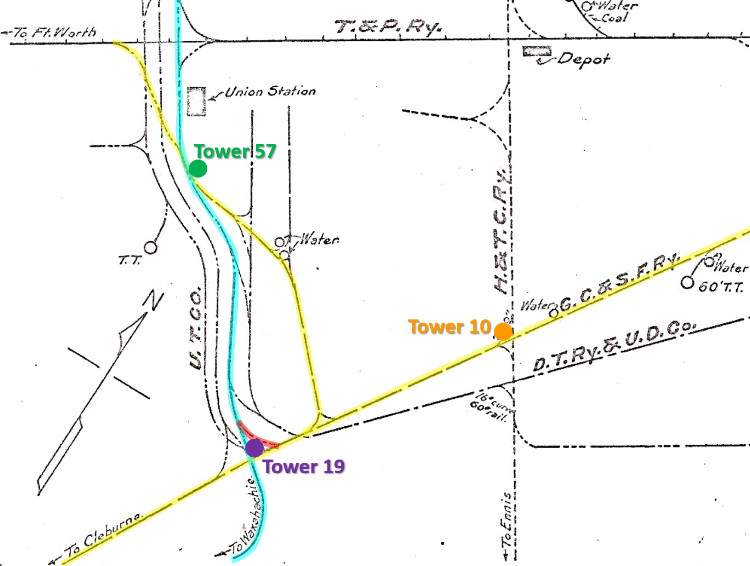

Left: This

1915 track chart from the Office of the Chief Engineer of the

Missouri, Kansas & Texas Railway Co. of Texas (the office was located

in Dallas) is highlighted to show three towers and the path of the Katy

(blue) and Santa Fe (yellow) tracks south of downtown. According to RCT

records, Tower 19 was

authorized to begin operations on July 27, 1903. It housed an electrical

interlocking plant with sixteen functions built by the Taylor Signal Co.

The specific function allocation has not been found, but it was most

likely a home signal, distant signal and derail in each of the four

directions, plus a switch and signal at each end of an exchange track.

Presumably the exchange track on this 1915 map (highlighted in red)

dated back to 1903. By the time this map was drawn, the plant at Tower

19 had increased to twenty functions, probably due to tracks of

two railroads that appear on the map: the Dallas Terminal Railway and

Union Depot Co. (DTR&UD, owned by the St. Louis Southwestern Railway --

its "Union Depot" never caught on with other railroads), and the Union

Terminal Co., which had been established by eight railroads to build

Union Station and associated switching tracks. Both would eventually be

added to the list of railroads that shared Tower 19's expenses.

Information released by RCT in 1916 confirms that Santa Fe had the

staffing responsibility for Tower 19. This was no surprise; Tower 19 was

a "Santa Fe tower" in all respects.

Tower 10 sat

less than a mile northeast of Tower 19 at Santa Fe's crossing of the

Houston & Texas Central (H&TC) Railway, a Southern Pacific

(SP) subsidiary. Tower 10 was a Santa Fe tower, as was

Tower 57 located 1.5 miles north of Tower

19. Tower 57 controlled the west end of downtown along the east bank of the Trinity

River near Union Station, which was still under construction in 1915.

Photos show Tower 57 to be virtually identical in architecture to Tower

19. When Union Station opened in October, 1916, Tower 57 was retired, replaced by

Towers 106 and 107, north and south,

respectively, of Union Station. (track chart, Ed Chambers Collection) |

The T&P tracks through downtown were relegated to

secondary status beginning in late 1920 when its trains began routing

south of downtown on the Katy's tracks and the

initial segment of the Dallas Belt Line to T&P Jct. At

least one additional track from Union Station to Tower 19 had

been built prior to 1915 (per the track chart), and in late 1920, a main line

parallel to the Katy was extended across the Santa Fe line all the way to

Metzger near Belt Jct. Previously, T&P trains would have been

a rare sight at Tower 19, but now they were a frequent occurrence, multiple

times each day. The additional tracks in the immediate vicinity of

Tower 19 belonging to the Union Terminal Co. and the DTR&UD also contributed

to increased workload in the tower. Both railroads eventually (DTR&UD in 1923, and Union Terminal Co.

in 1926) began sharing Tower 19's expenses. Between December 31, 1922

and December 31, 1923, the function count at Tower 19 increased 350%

from 20 functions to 90 functions, implying either a new

interlocking plant had been installed to increase capacity, or Tower 19 had

begun to control other interlockers remotely. It is possible that the asserted

1924 rebuild of Tower 19

could have been nearing completion in late 1923, and if so, Santa Fe would have

been able to incorporate the larger interlocking plant needed to support 90

functions. As it seems rather obvious to expand the tower's

physical capacity before -- or at least

coincident with -- its functional expansion, perhaps this is evidence that the

"1924 rebuild" was actually conducted earlier, sufficiently in time for

integration of the dramatic function increase reported operational by RCT at the

end of 1923. The second phase of the Dallas Belt Line was already in progress,

and it had predictable consequences for Tower 10. Santa Fe knew there would be

an eventual consolidation, supplying yet another justification for a larger

tower. Whenever it was built ... how this new tower building differed from

its predecessor is a subject for further research; the original design of Tower

19 remains undetermined.

With completion of the Dallas Belt Line

in 1926, SP freight trains began routing east of downtown through T&P Jct.,

reducing the traffic past Tower 10 as the original H&TC main line became

relegated to industry service. Ten years earlier, SP passenger trains had

started routing to Union Station using Katy and Union

Terminal tracks; this had also reduced Tower 10's traffic. On July 23, 1932, Santa Fe submitted a

proposal to combine Tower 10's functions into Tower 19. Two months later,

the RCT engineering staff recommended approval of the plan and it was granted by the

Commissioners. A new General Railway Signal Co. interlocking plant was

installed and the interlocker functions for Tower 10 were incorporated into

Tower 19, effective March 6, 1933.

RCT's Tower 19 documentation has references to "Interlocker10-19", perhaps the chosen

nomenclature for the new interlocking plant.

Whether the relocation of

Tower 10's functions into Tower 19 also included remote control of

Tower 22 has

not been determined.

Tower 22 was Santa Fe's crossing of the

original T&P main line east of downtown, about a quarter mile east of Santa

Fe's yard. By 1921, it would have been seeing substantially reduced traffic

because it was bypassed by the reroute of T&P traffic south of downtown. Tower

22 was staffed by T&P, and the date of its final demise is unknown. However, a

1961 RCT document references "Interlockers 10 and 22", suggesting that their

operational control may have been combined at some point, even if they remained

separate interlocking plants. Folding Tower 22's operations into Tower 10 would

have made sense c.1921. Remote control of the

Tower 22 interlocker was eventually assigned to Tower 19, but when this occurred

is undetermined.

|

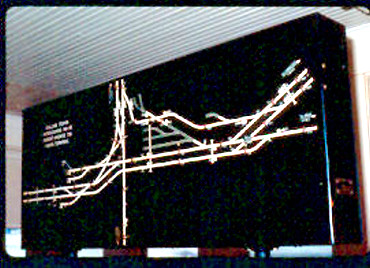

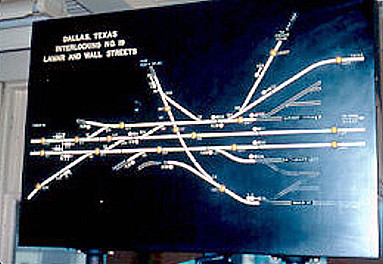

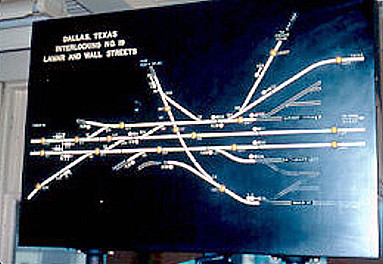

Right: The operator's

desk inside Tower 19 incorporated a track diagram at the top of the

console. As technology improved, functions that were once controlled

using the large handles on the

interlocking machine could be reduced in size and controlled by small

electrical switches. By 1984, Tower 19's functions were controlled by levers on the interlocking

machine in combination with electrical switches. By pulling or pushing the levers, the tower operator could align rail

switches and signals for a specific train movement. Once aligned, a

conflicting movement could not be aligned until after passage of the

first train. (Bob Courtney photo, 1984) |

|

On February 13, 1928, automatic block signals installed

by SP began operating between Belt Jct. and the Belt Line's intersection with

the Katy tracks at Forest Ave., 0.2 miles south of Tower 19. A year earlier, SP

had begun leasing its Texas railroads, including the H&TC, to the Texas & New

Orleans (T&NO) Railroad, designated to be SP's primary operating company for

Texas and Louisiana. In 1934, these leases became corporate mergers and the H&TC

ceased to exist. T&NO was included among Tower 19's expense-sharing railroads

at some point, but it is not listed as such in RCT's final comprehensive interlocker

table published at the end of 1930. Documentation at DeGolyer

Library states that H&TC began sharing Tower 19's expenses in February, 1928,

when operation of the automatic block signals commenced, suggesting that

monitoring indicators and override controls for these signals were incorporated

into Tower 19.

On March

14, 1958, RCT issued a memo to Santa Fe authorizing removal of nine specific

derails that were manually controlled by Tower 19, presumably in response to a

request by the affected railroads. Application was then made to the Interstate

Commerce Commission (ICC) for permission to remove the derails. The proposal was

jointly opposed by four railroad employee unions for safety reasons. The ICC

responded with a September, 1958 ruling

that begins by noting that the application had been filed jointly by all five railroads that "owned" Tower 19, the Katy, Santa Fe, Union Terminal Co.,

DTR&UD and T&NO. The ICC granted permission for removal of six of the nine

derails, including the five that dated back to 1918. Those were at the

point of needing to be removed or replaced -- they could no longer be maintained

as parts were unavailable. The other four derails had been upgraded to newer

technology when various track adjustments were made as part of a City of Dallas

project for grade separation of city streets in the vicinity of the Tower 19 and

Tower 10 crossings, a project that commenced in September, 1948. One of these

newer derails was also authorized for removal. The ruling provides some interesting background statistics:

in the month of May, 1958, Tower 19 saw 568 passenger trains and 641 freight

trains on the Katy tracks, and 62 freight trains on the Santa Fe tracks (Santa

Fe passenger trains did not pass Tower 19.) There was also an average of 7.8

daily switching movements on Santa Fe's tracks past Tower 19, and a total of

4,271 switching movements on the other tracks during the month.

By the

mid 1960s, RCT had recognized that it no longer had much, if any, regulatory

control over Texas' railroads. The ICC was fully regulating interstate

railroads, and all railroads had to comply with Federal safety regulations which

included grade crossing safety. Every rail line in Texas was subject to ICC

jurisdiction since every track regularly saw (or could

see) trains moving in interstate

commerce. RCT had recognized that it had inadequate engineering resources to

stay abreast of the rapid advances in railroad signaling and communications

technology that had begun in the 1950s. Instead, RCT had changed the focus of

its staff toward regulation of Texas' oil industry which was also within its

purview. Oil industry regulation was strictly a state responsibility with little

Federal involvement. The three RCT Commissioners had to face the voters every

two years, and many of these voters owed their jobs directly or indirectly to

the oil industry, or were otherwise affected by oil company practices,

production levels, and leasing and royalty policies for land and mineral rights.

The Commissioners knew where the votes were, and it was not in railroad

regulation. The last document in the Tower 19 file at DeGolyer Library is a 1967

memo regarding track changes being made by SP associated with an industrial lead

near the Tower 10 crossing, which had long been under Tower 19 remote control.

In 1990, Santa Fe sold its

Dallas yard and its tracks south toward Midlothian to the Dallas Area Rapid Transit

(DART) system. DART planned to use a portion of this right-of-way for a light

rail line into southwest Dallas (which ultimately became the DART Red Line.) In 1991, the Southwest

Railroad Historical Society (SRHS) began efforts to acquire and preserve the tower. Even though DART

now owned the rail line, the tower was still in service. The original plan was

for Tower 19 to remain where it was until it was removed from service. However, Union Pacific

(which had acquired the Katy) needed additional time to make changes to support

removing Tower 19 from service. To prevent delaying construction

of the light rail line, Tower 19 had to be relocated. It was removed from its first

floor concrete foundation and shifted about 50 feet east. It rested

on movers beams, but had all necessary control functions re-connected

for service.

The tower was finally removed from operational service in the summer of 1993.

For more than two years, it remained near the crossing,

unused and unprotected except for boards over the windows, suffering vandalism

with most

of its copper wiring stripped out. Fortunately, most

of the damage was on the lower floor; the upper floor, including

the interlocking machine and track diagram, remained intact. In August, 1996, the

tower was moved

to the SRHS-sponsored Age of Steam Railroad Museum at Fair Park in Dallas and installed on a

concrete pedestal to reproduce its operational height. The move was documented

in the October, 1996 issue of Clearance Card, an SRHS

publication. In March, 2012, it was

relocated to the

Museum of the American Railroad in Frisco, Texas for permanent preservation and

restoration.

These Tower 19 photos are from the Historic

American Engineering Record (HAER), Library of Congress. They are identified as a component of

HAER "...documentation compiled after 1968", which unfortunately says

nothing about the actual date the photos were taken, which remains undetermined.

Above: The Santa Fe tracks ran

along the short side of the tower. Note the outline of clean boards that were added to fill in a lower

story window. The adjacent sheds were storage for track and tower maintenance

equipment. Below Left: The

long, front side of the tower had the staircase and faced the Katy tracks. A window

on the lower story to the right of the door (by the "19" placard) has been boarded up.

Below Right: On the back side of the tower, two large windows

on the lower story are boarded up. Preservation efforts at the Museum of the

American Railroad have restored all of these windows.

|

Left: MKT GP 94

passes Tower 19 heading to Dallas Union Station in February, 1980.

Right:

A Santa Fe caboose passes Tower 19 in September, 1982. Note that the front,

lower story window to the right of the door is intact.

(both photos by

Myron Malone) |

|

Above Left: By September

1992, the diamond connecting the Santa Fe Dallas Yard to its line to Cleburne

had been removed. The sale of the Santa Fe property to DART and the associated

changes that would put Tower 19 out of service had begun. In the background, a

Kansas City Southern (KCS) train can be seen; KCS had acquired Santa Fe's tracks

as far as Farmersville on the Paris line, and it used the Santa Fe

yard as the

interchange point with other railroads in Dallas. (Myron Malone photo) Above Right: Tower

19 was

moved in August, 1996 to Fair Park and placed on a newly

poured concrete base to match the original height of the tower. (Hume Kading

photo)

|

Left:

With the tower removed, DART constructed a grade-separated crossing for

its light rail line to south Dallas, passing over Union Pacific's ex-MKT

tracks. (Microsoft Virtual Earth c.2008)

Above & Below: Track

diagrams located at Tower 19's interlocking control consoles had various

small lights to indicate the presence of trains. (Bob Courtney photos,

1984)

|

Tower 19 Drawings

from the Historic American Building Survey are here.