Two Crossings of the St. Louis Southwestern Railroad at Plano

|

Left: Tower 49 is visible on the right side of this undated image from the John W. Barriger III National Railroad Library. Barriger took the photo facing east from the rear platform of his business car at the tail end of a St. Louis Southwestern ("Cotton Belt") train westbound through Plano. Behind Tower 49 from this angle sits the joint Cotton Belt / Southern Pacific (SP) depot. The bright white cabinet adjacent to the platform at right is a shed that housed equipment for the Tower 166 interlocking plant that managed the Cotton Belt's crossing of the Texas Electric (TE) Railway. The top of the shed sloped downward toward the TE tracks in front of it. A TE interurban car is barely visible left of center, mostly obscured by trees, no doubt waiting for Barriger's train to pass. That Tower 49 was built by SP is obvious even from this distance as it closely resembles other SP towers in Texas (e.g. Tower 21, Tower 95 and many others.) |

When the Houston & Texas Central (H&TC) Railway built north from

Houston toward the

Red River in 1872, it passed through an unnamed settlement immediately north of

Dallas. A year later, nearby residents incorporated

a town known as Plano, Spanish for flat or plain, accurately describing the local

terrain. The H&TC became part of the Southern Pacific (SP) system

in 1883, and in the late 1920s, the H&TC was leased to the Texas & New Orleans (T&NO) Railway,

SP's principal operating company in Texas. The H&TC was fully merged into T&NO

in 1934.

In 1888, Plano's economy benefitted

from the arrival of a second railroad, the St. Louis, Arkansas and Texas (SLA&T)

Railway, which built west through Plano about a half mile south of downtown.

The SLA&T had been created in

February, 1886 by a bankruptcy

judge overseeing the receivership of the Texas & St. Louis (T&SL,

"Cotton Belt") Railway. The timing of the SLA&T's creation went against the advice of T&SL President Sam

Fordyce who believed that unsolved operational issues would inhibit the new

railroad's profitability. At

the time, the

T&SL consisted of a narrow gauge line from Tyler

to Texarkana continuing across Arkansas and

Missouri as far as Bird's Point on the Mississippi River. The tracks to Bird's

Point were completed in 1884, but the effort overextended the company's

finances, sending the T&SL into receivership. Fordyce had many concerns, one

of which was that insufficient passing sidings on the lengthy track to Bird's

Point made it difficult to operate efficiently. Nevertheless, the

judge terminated the receivership, creating the SLA&T to become the new Cotton Belt.

With Fordyce at the helm, the SLA&T promptly converted its tracks to standard gauge and began building

new branch lines in north Texas. The SLA&T's primary branch departed the main

line at Mount Pleasant and went west to Commerce. There, it split into two

branch lines continuing west: one to Sherman and a

much longer one to Fort Worth. The Fort Worth line

from Commerce ran generally southwest, passing through Greenville in Hunt

County, and future Dallas suburbs in

southern Collin County (Plano) and northern Dallas County (Addison and

Carrollton.) A 12-mile Cotton Belt branch line into

downtown Dallas was built from Addison c.1903.

Fordyce was attempting to compete with rail baron Jay

Gould on traffic at Sherman and

Fort Worth. Gould was simultaneously President of

three major Texas railroads: the Missouri, Kansas & Texas (MK&T, "Katy") Railway, the Texas &

Pacific (T&P) Railway, and the International & Great Northern

(I&GN) Railroad. In various ways, all three were leased to Missouri Pacific (MP),

a major St. Louis railroad controlled by Gould in which he held a substantial

ownership stake. While his railroads effectively

controlled access to St. Louis from the Texas gateways

at Texarkana and Denison,

Gould was concerned that the SLA&T line from Texarkana across Arkansas and

Missouri could become a serious competitor for Midwest traffic. Gould also

understood that the SLA&T was experiencing continued financial difficulty stemming from the premature

termination of the T&SL receivership. Gould saw

this as an opportunity to take over the Cotton Belt, so he proceeded to make a secret agreement with Fordyce to cooperate on traffic through Texarkana.

At the same time, Gould began to gain financial leverage over the SLA&T with

direct loans and stock purchases, positioning him to guide the company's reorganization when it became insolvent in 1889 (as

Fordyce had predicted.)

In 1891, the SLA&T's bankruptcy plan created

yet another new

railroad, but this one would be dominated by Gould. It was known as the St.

Louis Southwestern Railway (SLSW or SSW), but more commonly just the Cotton Belt. Gould installed his younger son Edwin

as President of the Cotton Belt, and Edwin held that title until his retirement in 1925.

A series of ownership changes in the late 1920s resulted in the Cotton Belt

becoming a subsidiary of SP in 1932, but SP

continued to operate the Cotton Belt

separately until it was merged in the 1990s.

Above: This map shows

northeast Texas railroads c.1899 (not all railroads shown.) By this time, Jay Gould

had been fired by

Katy stockholders (1888) and the new Katy management had sought

bankruptcy protection from the courts. In 1890, the Texas Supreme Court broke

MP's lease of the Katy, which returned to being an independent railroad,

depriving Gould of control over the Denison gateway. Also in 1888, the St. Louis & San

Francisco ("Frisco") Railway had opened a new gateway to the Midwest at

Paris, providing yet another alternative to Gould

railroads for access to St. Louis and the Midwest. The Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe

Railway benefitted from the Paris connection and began running single-train

passenger service with the Frisco between Dallas and St. Louis. Likewise, the

Texas Midland (TM) joined with the Frisco and the H&TC to run single-train

service between Houston and St. Louis via Ennis and Paris, using trackage rights

on the Cotton Belt to cover the segment between Greenville and Commerce. When

Jay Gould died in late 1892, he was succeeded by his elder son George as

President of the T&P, the I&GN and MP. The Gould family continued to have a

major presence in Texas railroading, but among the three gateways to the Midwest from Texas,

the Gould family only controlled Texarkana.

In 1901, a new Texas law gave the Railroad Commission of Texas (RCT) the authority to regulate crossings of two railroad companies. RCT immediately began to require swing gates with STOP signs installed at major crossings to provide a minimum level of safety. All trains were still required to stop at all grade crossings of another railroad, so the gates only served to provide additional warning for approaching trains. [In later years, trains were allowed to approach gated crossings at restricted speeds, proceeding without stopping if the gate was open.] In 1902, RCT began ordering specific crossings to be protected with interlocking plants, home and distant signals, and derails. Crossings were typically outfitted with 2-story towers to house the interlocking plant and to provide observation space from which operators controlled the signals and derails through the interlocker.

|

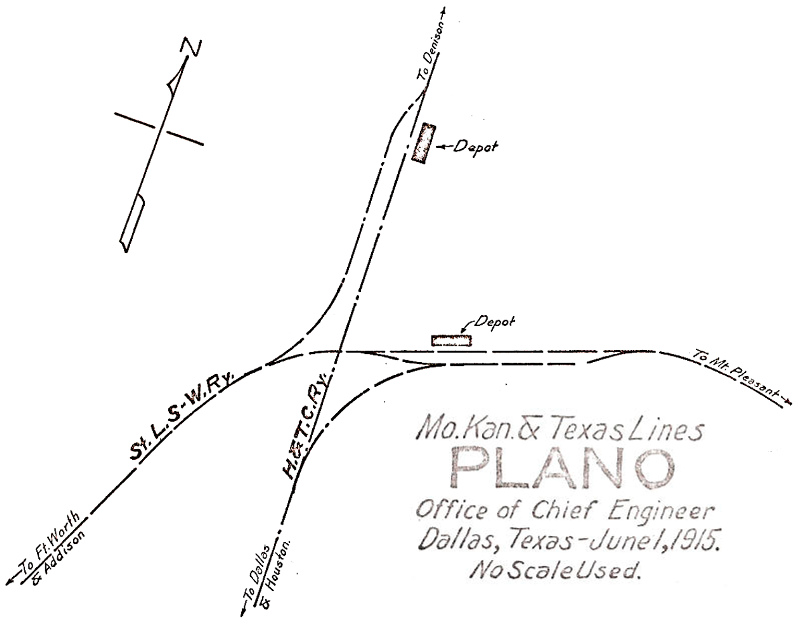

Tower 49 was commissioned by RCT at the H&TC / Cotton

Belt crossing on July 18, 1904. It housed a 36-function electric

interlocking plant with 26 control levers. The large function count

indicates the presence of connecting tracks with switches, derails and signals controlled through the interlocker. Left: The Katy Railroad drew this track chart of Plano in 1915, before there was a joint depot (Ed Chambers collection.) Below: This 1926 T&NO track chart of Plano shows the TE interurban line parallel to SP's H&TC main line. Tower 49 is depicted by the black square at the H&TC / SLSW crossing. The TE line was built by the Texas Traction Co. in 1908, and its crossing of the SLSW was uncontrolled until Tower 166 was installed in 1931. (Carl Codney collection)  |

|

|

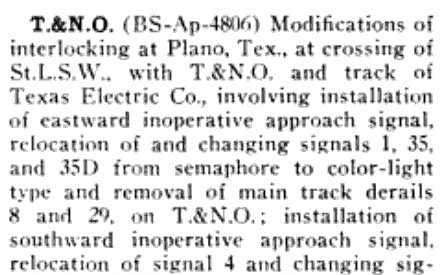

Left: The May, 1943 issue of Railway Signaling carried this news item describing major changes to the interlocking plants at Plano. The "...installation of indicators on Texas Electric Co. tracks and inclusion of crossing in the interlocking..." implies that the Tower 166 plant was being merged into the Tower 49 interlocker, a money-saving move facilitated by the proximity of the two crossings. Perhaps the most significant detail was "...moving interlocking machine from tower to depot." The joint SLSW / T&NO depot at the crossing would host the operators for Tower 49, setting in motion the demise of the tower structure. The TE / Cotton Belt crossing remained active until the TE stopped service on its entire network at the end of 1948. |

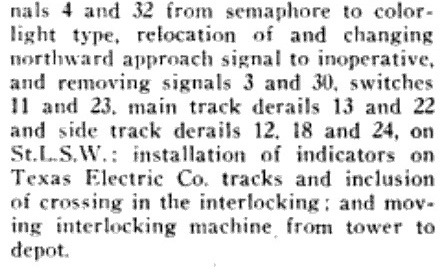

| Right: An Employee Timetable issued by T&NO on May 19, 1946 listed these whistle codes for the Tower 49 interlocking. Locomotive engineers used the whistle to signal operators (who were at the depot by 1946) to make appropriate switch and signal alignments for specific moves. |  |

As early as 1943, Dallas city planners had examined the possibility of repurposing the Cotton Belt right-of-way from Addison into downtown Dallas to become a motor vehicle expressway. Since the Cotton Belt had become owned by SP ten years earlier, the belief was that Cotton Belt trains could instead access downtown Dallas from Plano using a connecting track at Tower 49, making the Addison branch superfluous. The 1957 Dallas Master Plan formally made this recommendation, triggering a feasibility study conducted in 1961. For funding purposes, the proposed expressway was to be built as a toll road under the Texas Turnpike Authority (TTA) which already operated a major toll road between Dallas and Fort Worth. The TTA approved the plan in 1964 and construction commenced soon thereafter. Cotton Belt trains began using the T&NO tracks from Plano to reach downtown Dallas. The Dallas North Tollway opened on the former Cotton Belt right-of-way in 1968. The T&NO north / south line remained in service through Plano until the early 1990s (by which time the T&NO had been dissolved and merged into SP.) The Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) system acquired the right-of-way in 1988 for future use in the construction of an electrified light rail line (the Red Line) serving Plano from downtown Dallas.

|

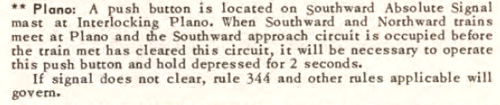

Left: The Tower 49

automatic interlocker cabin sits in the northwest quadrant of the Plano

crossing in this photo taken prior to the start of DART construction.

The camera is facing south along the SP rail line with the former

Cotton Belt line passing horizontally across the image. This is

undoubtedly the original automatic interlocking cabin dating to the

late 1950s or early 1960s (Jim King photo, 1997.) Below: At least by 1962 and perhaps earlier, the Tower 49 interlocking plant became automated. A Cotton Belt Employee Timetable (ETT) dated January 1, 1962 listed the Plano T&NO crossing in its table of automatic interlocking plants. The entry included this special note.  |

In 1948, the construction of Lake Lavon commenced near

Wylie, a small town northeast of Dallas. Santa Fe's line between Dallas and

Paris passed through Wylie and portions of it had to be relocated due to

the lake's construction. Several miles east of Plano, the Cotton Belt line also

passed through Wylie but it was not directly affected by the construction.

Upstream flooding in 1990 necessitated heavy releases of water through the Lake

Lavon dam, seriously damaging the Cotton Belt's tracks and its bridge over the East Fork of the

Trinity River below the dam. Rather than rebuild, SP chose

to abandon 23 miles of Cotton Belt tracks between Wylie and the western outskirts

of Greenville. West of Wylie, the Cotton Belt tracks remained in place but were

taken out of service. The right-of-way was sold to DART in 1990 for future

transit use.

In 1995, Kansas City Southern (KCS) Railway reached

an agreement with DART for rights to use the dormant Cotton Belt tracks enabling

KCS service to be

activated west from Wylie through Plano. Several miles west of Plano, the tracks

connected to a KCS line acquired from Santa Fe that went northwest from

Garland to a connection with a Santa Fe main line (to Oklahoma) at Dalton Junction near Denton. The result was a shortcut across southern

Collin and Denton counties that allowed KCS trains coming out of Santa Fe's Alliance Yard north of Fort

Worth to bypass Garland and proceed through Plano to Wylie where KCS built a major

yard. East of Wylie, the line continued to Farmersville on former

Santa Fe tracks (acquired by KCS in 1993 though it had held trackage rights for

decades.) At Farmersville, KCS turned due east to Greenville on

tracks (originally of Katy heritage) that KCS had acquired in 1939. Farther east, the KCS line continues to Meridian,

Mississippi by way of Shreveport. The end result was a major KCS east / west line

from Fort Worth to Mississippi that passed through Plano on the former Cotton Belt tracks.

Above Left: This aerial view

of the Tower 49 crossing dates from 1938 ((c) historicaerials.com.) The Cotton Belt tracks (blue arrows) crossed

the T&NO tracks (pink arrows) at Tower 49 (pink oval) and crossed the TE

interurban tracks (yellow arrows) at Tower 166 (yellow circle.) Note the

interlocker electronics cabin in the southeast quadrant of the Tower 166

crossing; this was several years before Tower 166 was merged into Tower 49.

There were T&NO / Cotton Belt connecting tracks (green arrows) in the northwest

and southeast quadrants of the Tower 49 diamond. The southeast connector across

from the depot (red arrow) appears disconnected, but the 1915 Katy track chart

shows it connecting to a Cotton Belt siding rather than the main line. There was

also an exchange track (orange arrow) between the Cotton Belt and the TE

interurban line; note the railcar (orange oval) on the connector. Railroads sometimes exchanged box cars with interurbans, and

this was not the only such connection for the TE (e.g. Tower 167 at

Hillsboro and a Katy / TE exchange track near

Tower 35 in Dallas.)

Above Right: This March, 2025 Google Maps satellite

image with the same view shows how much has changed. In particular, the former

Tower 49 crossing is now obscured by the DART Red Line tracks. The Red Line's

new 12th St. Station is visible straddling the tracks with six covered areas for

passengers. The wide curved right-of-way to the right of the Red Line is the new

Silver Line under construction. The 12th St. Station for the Silver Line also

has six covered areas for passengers (note orange roofs.) Enabling KCS to

continue to use the right-of-way created a significant design challenge for the

DART Silver Line.

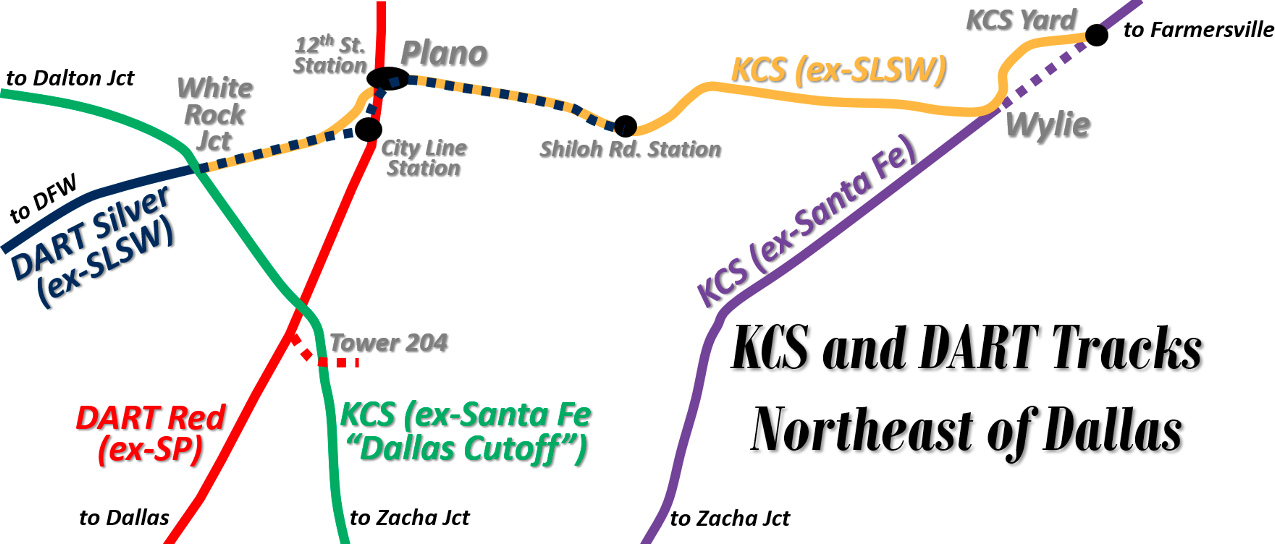

Above: This map shows the freight

and DART tracks in northern Dallas County and southern Collin County (not all

rail lines shown.) In November, 2025, DART opened its Silver Line between DFW

Airport and Shiloh Rd. Station in Plano. This was a complex undertaking because

segments of the Silver Line tracks remain in use by KCS freight trains. All

other DART lines are electrified, but the Silver Line is a commuter rail design

using diesel-electric locomotives, hence there is no overhead electrification

(which would otherwise interfere with double stack freight trains.) All DART lines are double tracks, but on the

Silver Line, the north track is also used by KCS freight trains between White

Rock Junction and Shiloh Rd. Station, except for a two-mile segment either side of City Line Station. Between 12th St. Station and a point one mile

west of City Line Station, the Silver Line does not follow the Cotton Belt

right-of-way. Instead, it runs farther south so that it can serve the large

employee population at the City Line development. The KCS route (on the original

Cotton Belt right-of-way) is more direct, requiring only about 1.3 miles to

cover the distance between 12th St. Station and the reconnection point west of

City Line Station.

At White Rock Junction, KCS trains move between the former

Santa Fe "Dallas Cutoff" and the former Cotton Belt line, providing a

shortcut

between Dalton Junction and the KCS yard near Wylie. Previously, KCS trains

between those endpoints had to transition through Zacha Junction. Santa Fe

created Zacha Junction when it built the cutoff to Dalton Junction in 1955

(which involved crossing SP's Arapaho Spur, resulting in the establishment of

Tower 204 in Richardson.) The

original Santa Fe line from Dallas through Wylie was built c.1887 as part of Santa Fe's

main line between Dallas and Paris. At Wylie, the original Santa Fe

alignment through the city has been abandoned (purple dashes.) Trains coming

north from Zacha Junction now merge onto the Cotton Belt alignment to swing

around the north side of town to reach KCS' yard. East of the yard, the Santa Fe

alignment to Farmersville is used. This alignment was revised between Wylie and

Copeville in the early 1950s due to the construction of Lake Lavon. Originally, the Cotton Belt and Santa Fe main lines had an uncontrolled

grade crossing on the northeast side of Wylie. Santa Fe's revised alignment to

Copeville resulted in a grade-separated crossing that KCS still uses to pass over the Cotton Belt right-of-way, which now hosts Farm

Rd. 384 instead of Cotton Belt tracks.

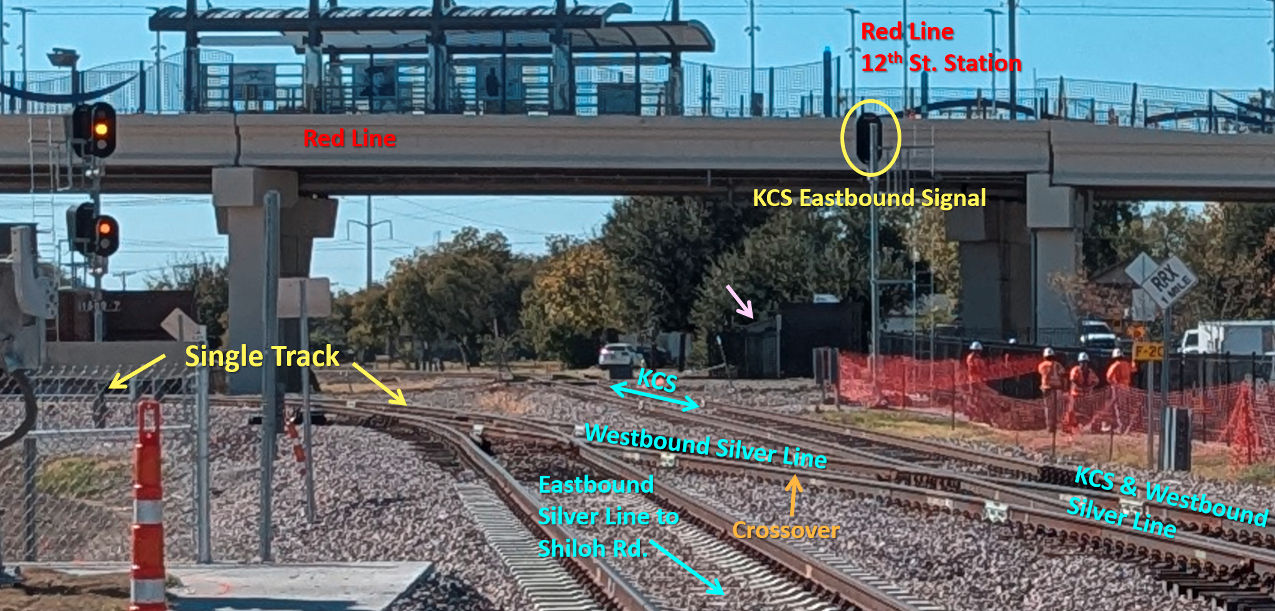

At 12th St., new DART stations were built for both the Silver Line and the Red Line (which did not previously have a station there.) The Red Line station is elevated on DART's bridge over the KCS tracks (sitting directly above the Tower 49 crossing site.) The Silver Line station sits at ground level about a tenth of a mile to the east, necessitated by the real estate needed for the station and parking lot. Just east of the elevated Red Line tracks at 12th St. Station, the Silver Line transitions from double track to a single-track segment, curving south as it passes beneath the Red Line bridge to occupy a narrow space parallel to (and west of) the Red Line almost all the way to City Line Station. The Silver Line reverts back to double track with a switch beneath the Hwy 190 tollway about a hundred yards north of City Line Station. There, the unswitched route carries Silver Line eastbound (northward) trains accelerating out of City Line Station. The switched route is for Silver Line westbound (southward) trains slowing for the stop at City Line Station. The total length of the Silver Line's single-track segment is approximately three quarters of a mile. At City Line, DART's existing Red Line station was expanded to make room for the Silver Line tracks and its passengers. At the south end of City Line Station, the Silver Line double track curves west to proceed a mile to the junction point with the KCS track to resume the Cotton Belt alignment to White Rock Junction.

Above: Looking west, the

elevated Red Line passes over the Tower 49 interlocker cabin (pink arrow) barely

visible in the shadows and partly obscured from this direction. The two Silver

Line tracks in the foreground handle eastbound (left, south track) and westbound

(right, north track) trains, but the north track also handles all KCS trains in

either direction. A short crossover track (orange arrow) forms the north

end of the Silver Line's single-track segment which continues off the image to

the left. The white car visible near the center of the image is parked in a

driveway at the south end of Ave. I which sits atop the former TE right-of-way,

terminating at the KCS tracks. Below Left:

After passing beneath the elevated Red Line in the image above, the Silver Line

single-track heads due south toward

City Line along the west side of the Red Line. In this view from 10th St., the Silver Line rises in the distance to

match the Red Line height as the tracks go over Plano Parkway.

Below Right: Looking south

from the westbound service road of the 190 Tollway, the switch in the foreground

marks the south end of the Silver Line's single-track segment. City Line Station is just

beyond the car crossing the tracks on the eastbound service road of the 190 Tollway. (all

photos by Jim King, November, 2025.)

Above

Left: An eastbound Silver Line train is about to enter the

single-track segment beneath the 190 Tollway as it accelerates north out of City Line Station.

Above Right: Having crossed

the 190 Tollway westbound service road at grade, the Silver Line train continues

north, gaining

elevation to pass over Plano Parkway. Note the Red Line

tracks at far right with overhead power wiring.

Below Left: It is unclear what purpose the Tower 49

interlocking cabin serves in 2025, but

tool storage for maintenance workers seems like a good answer. It seems unlikely

that an abandoned cabin would have survived the major construction in this area. On this

particular weekday, there were numerous workmen in the area cleaning up various

construction details nearby. Below Right: The Tower 49 cabin sits directly

below the Red Line's 12th St. Station. The Silver Line single-track is visible

in the foreground curving south (left) to pass beneath the Red Line and head to

City Line Station.