Texas Railroad History - Towers 57, 106 and 107 - Dallas

West End and Union Station

A Major Railroad

Junction at

the West End of Downtown Dallas

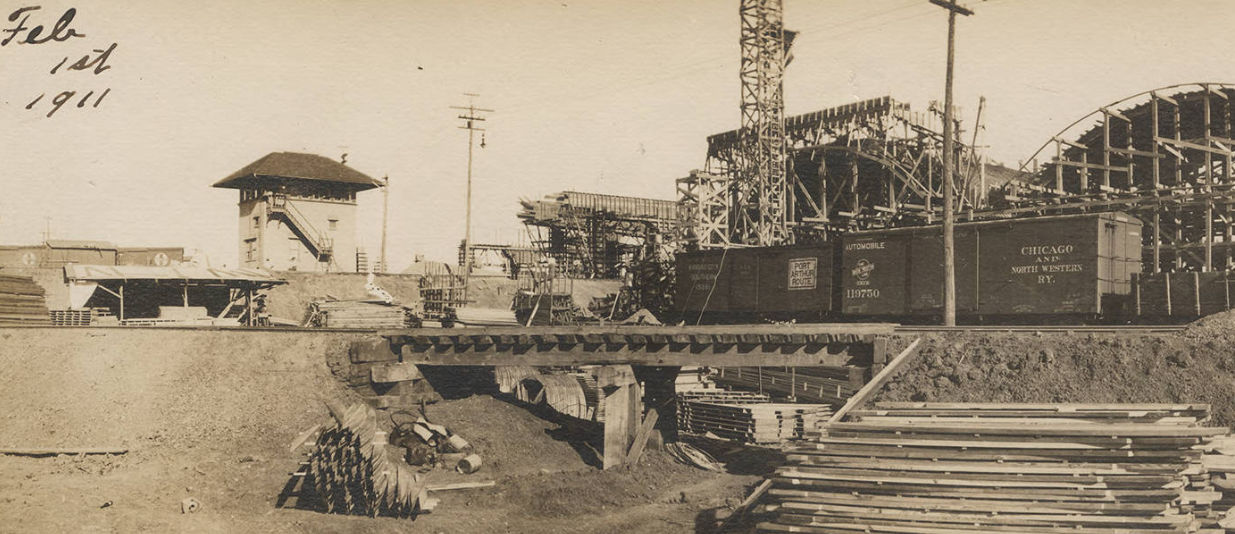

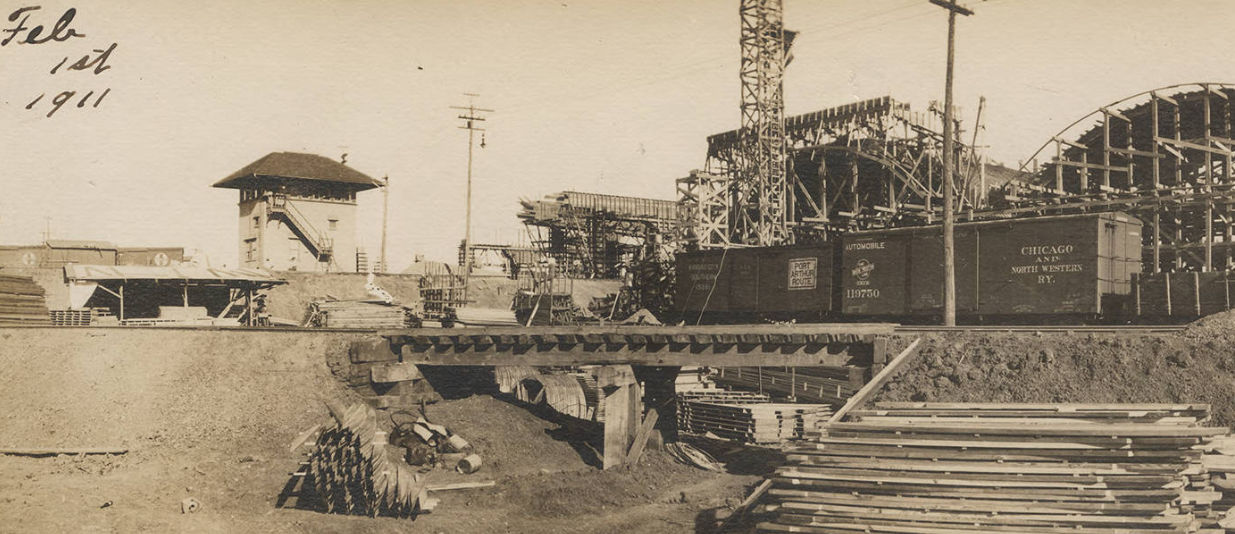

Above and Below: These two

images of Tower 57 are taken from two larger digitized photographs in

the

George W. Cook Collection maintained at DeGolyer

Library, Southern Methodist University. Both photographs face

generally east toward downtown Dallas and were taken on February 1, 1911 during

the construction of the Dallas - Oak Cliff Viaduct. From this direction, the

berm in front of the tower, which carried tracks of the Chicago, Rock Island &

Gulf Railway, blocks the full view of the tower's base. The construction of the

viaduct necessitated raising the tower so that operators could see over the

roadway to the south, but whether that effort has been completed cannot be

discerned from the photos. The viaduct crossed

over the Trinity River from downtown Dallas into the community of Oak Cliff on the

opposite bank. Boxcars belonging to the Kansas City Southern

Railway ("Port Arthur Route") and the Chicago and North Western Railway (left

and right, respectively) are visible on what appear to be temporary tracks built to

support construction.

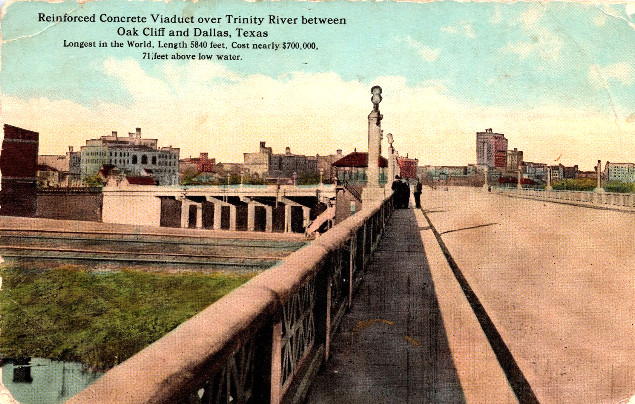

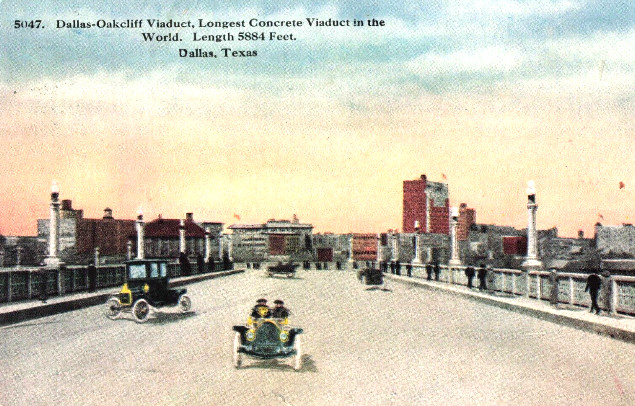

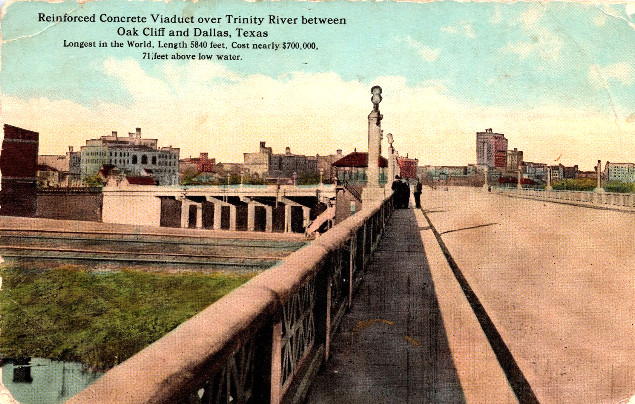

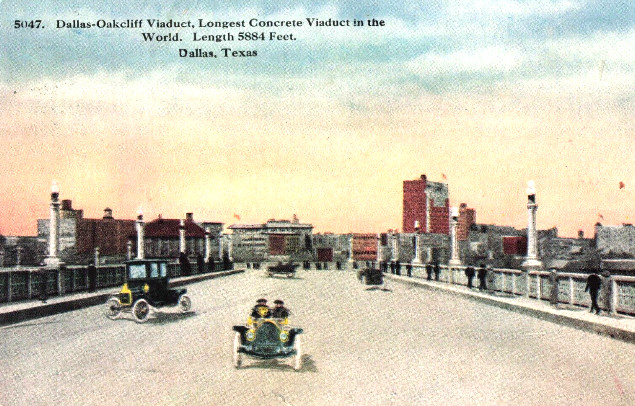

The viaduct was built between October,

1910 and February, 1912 funded by the sale of

bonds issued by Dallas County. It is on the National Register of Historic Places as

the longest reinforced concrete highway viaduct

in the world at the time it opened (a longer one existed, used by a railroad.)

It has 51 concrete arches plus additional spans at the approaches and a steel

span over the main channel of the river. Its length varies by the criteria used

in the measurement, e.g. only the reinforced concrete sections or including

earthen fills, concrete-encased steel spans, and concrete T-beam spans. The

Texas Historical Commission claims 6,562 ft., the Historic American Engineering

Record compiled in 1996 says 5,106 ft., and the National Bridge Inventory lists

4,774 ft. Due to a horizontal clearance requirement, the segment of the viaduct

directly over the main channel of the Trinity is a 98-ft. concrete covered steel

plate girder. On the Dallas end of the viaduct, Houston Street begins parallel

to the river and rises as it proceeds south. It makes

a 47-degree turn to the southwest as it increases its elevation to reach the

proper height to cross the river. On the Oak Cliff side, the viaduct flows

onto Zang Boulevard, the namesake for a previous bridge that crossed the Trinity

nearby. The name has been changed to the Houston St. Viaduct and it has

been a one-way (westbound) thoroughfare to Oak Cliff since the opening of the

adjacent Jefferson St. Viaduct in 1973.

By the time the Railroad

Commission of Texas (RCT) began regulating grade crossings among railroads in 1902, Dallas was already a major city served by

multiple steam railways and an electric interurban. In the decades after the

first railroad entered Dallas in 1872, a mass of tracks had descended upon the

central business district, converging near the east bank of the Trinity River at

the west end of downtown. The Tower 57 interlocker was commissioned by RCT on

November 5, 1904 to manage the junction. The interlocking plant was an

electrical design with 50 functions spread over 41 levers. The Gulf, Colorado &

Santa Fe Railway, a Texas-based subsidiary of the vast Atchison, Topeka & Santa

Fe Railway, was given official responsibility for managing the design and

construction of Tower 57, which ended up closely resembling Tower 19,

another Santa Fe-designed tower less than two miles to the southeast. Santa Fe

shared the capital and recurring expenses for Tower 57 with four other

railroads: the Missouri, Kansas & Texas, the Rock Island, the Dallas Terminal

Railway and Union Depot (DTR&UD) Co., and the Northern Texas Traction Co., an

electric interurban. The DTR&UD was owned by the St. Louis Southwestern ("Cotton

Belt") Railroad, which had acquired it in 1901 for the purpose of building a downtown passenger station.

This was the

first attempt to establish a "Union Depot" for Dallas, but no other railroads

joined this effort. For the twelve months ending June 30, 1906, RCT reported an average of 412 movements through the

Tower 57 interlocking each

day, comprised of 44 "train movements" and 368 "switching movements." It was a

busy place!

|

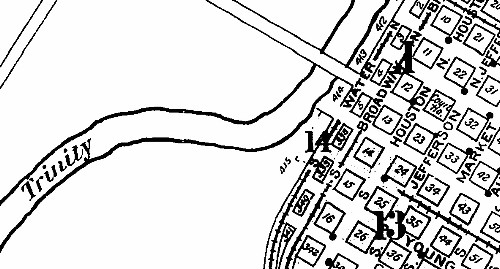

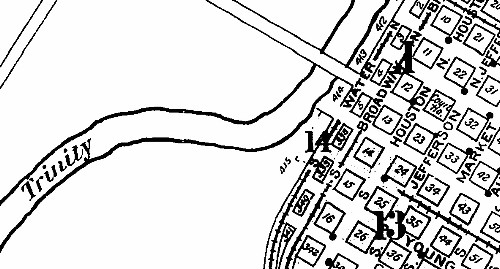

Left:

A detailed map in the 1905 Sanborn Fire Insurance Co. map set of Dallas

shows the unidentified Tower 57 (red oval) where the tracks on Water and

Broadway streets converge and cross. This was also the south end of

Houston St. where the viaduct would turn southwest in 1912. The location

of Tower 57 is well-known by the photos that show it adjacent to, and

north of, the viaduct near the turn. Jefferson Ave. is now Record St.,

and Broadway and Water streets no longer exist.

The following railroads have

been highlighted on the map as their labels are illegible at this

resolution:

The

Cotton Belt entered downtown from the north to reach the DTR&UD passenger station built in 1903. This was a branch that came off their line at Addison

between Commerce and Ft. Worth.

Santa Fe tracks from the south ran adjacent to the tower and terminated

in downtown. This was a short branch off their line between

Cleburne and Paris.

Tracks of the Missouri, Kansas & Texas (MK&T, "Katy") passed near

the tower and continued south to Hillsboro and north to Denton. At

Denton, they intersected a shared line of the Katy and the Texas &

Pacific (T&P) that ran between Whitesboro and

Ft. Worth. The T&P also

had

east/west tracks through downtown Dallas several blocks north of Tower

57.

The Rock Island tracks are visible on the berm in the photos

above. They continued north along Water St. and then turned west

to cross the Trinity and proceed to Ft. Worth.

They also went southeast to a junction with Southern Pacific (SP) south of

downtown. |

In RCT's annually published list of interlockers dated October 31, 1905, Tower 57 appears for the first

time, identified as "Dallas, Water St." It was an appropriately named

street, literally beside the east bank of the main channel of the Trinity River in downtown

Dallas. Hence, Water Street -- unpaved and mostly occupied by rails -- was inundated

anytime there was a flood on the Trinity.

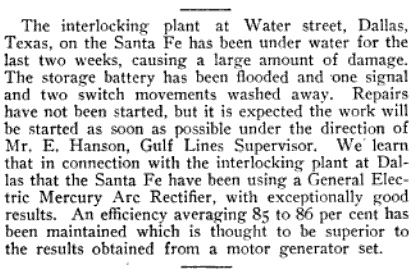

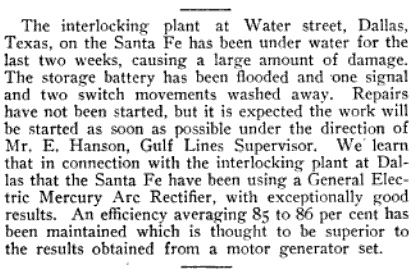

Near Right: Water St.,

adjacent to the Trinity River (1899 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map of

Dallas)

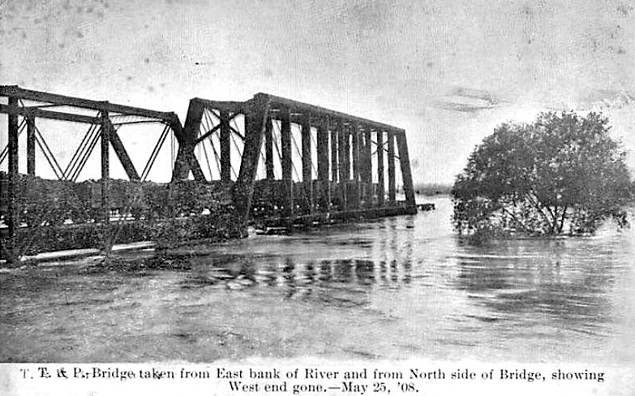

Far Right:

The Great Trinity Flood of 1908 resulted in heavy damage to Tower 57.

(The Signal Engineer, June,

1908) |

|

|

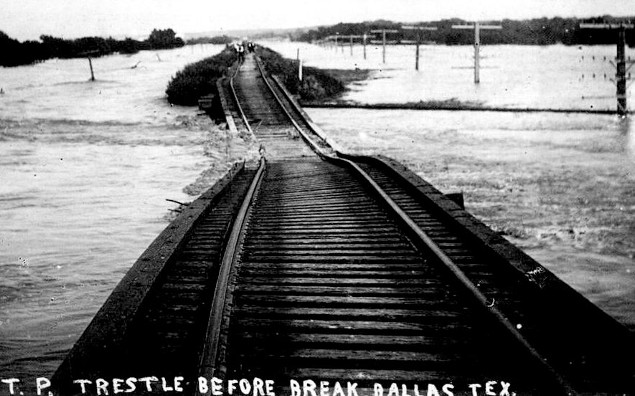

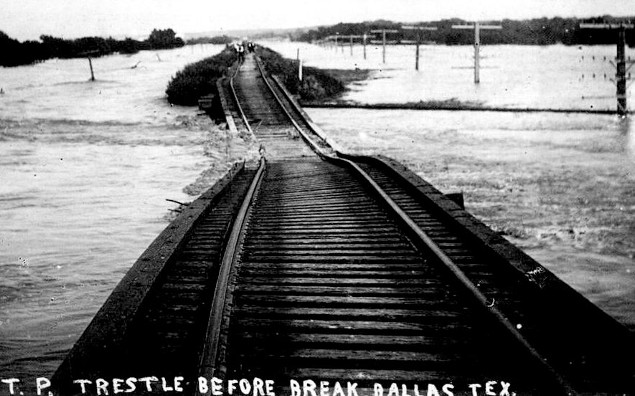

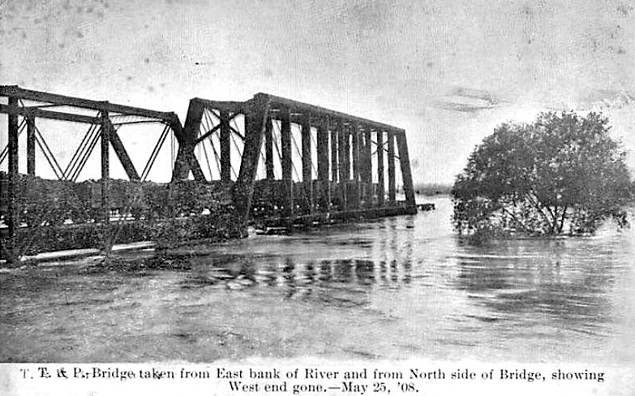

The Great Trinity

Flood of 1908 changed the course of Dallas history, providing the impetus to

reengineer many aspects of Dallas' physical infrastructure. The flood destroyed

the three public road bridges over the Trinity at Dallas, temporarily

making ferry services necessary for travel across the river. Five railroad bridges (the Rock Island, the Santa

Fe, the Southern Pacific, the Katy and the Texas & Pacific) were heavily damaged or

destroyed, and there were others that failed outside of Dallas County (e.g. the

Texas Midland bridge at Rosser -- see below.) The river was reported to be

two miles wide between downtown and West Dallas (four miles wide at Farmers

Branch, according to one newspaper report.) As Dallas' electrical power

plant (visible in the image above right)

was knocked offline, telephone and telegraph service was disrupted for several

days. The deaths of eleven people were attributed to the flood, some 4,000 people were left homeless,

and Dallas' municipal drinking water system was

rendered

inoperable. [All four photos are from the George W. Cook collection, DeGolyer

Library, SMU.]

|

|

|

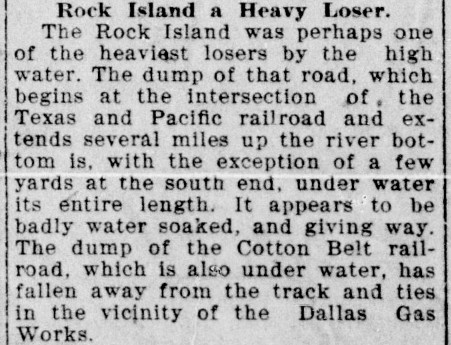

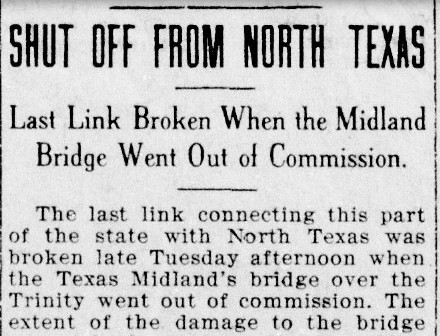

Note that

'Central' meant "Houston & Texas Central" (H&TC), a SP subsidiary. All snippets are from the

Waxahachie

Daily Light of Wednesday, May 27, 1908. |

|

|

|

|

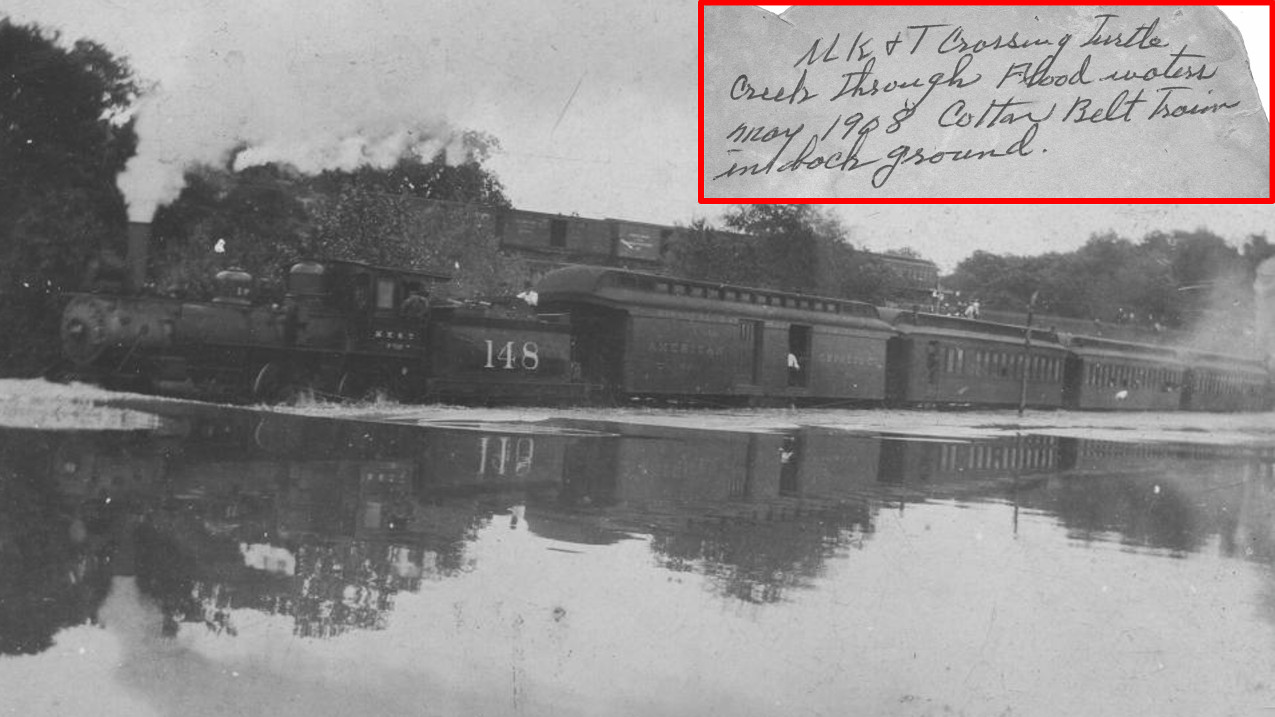

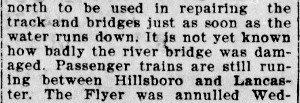

Above: Katy #148 slogs

through the Turtle Creek overflow with the Cotton Belt behind it on a higher

trestle. The creek is a tributary of the Trinity that runs through much of north

Dallas collecting a substantial amount of storm water runoff. Both of these

railroad rights-of-way have long been abandoned for other civic uses,

specifically the Dallas North Tollway (ex-Cotton Belt right-of-way reused in the

1960s) and the Katy Trail (right-of-way preserved after track abandonment in the

1990s.) (Dallas

Municipal Archives)

George Kessler moved to Dallas as a young child with

his family, arriving in 1865. A native of Germany, he went back to Europe for

university studies and then returned to the United States, becoming a renowned

city planner and landscape architect. In 1909, the Dallas Chamber of Commerce hired him to

create a comprehensive development plan for Dallas in the aftermath of the

flood. A few years earlier, Kessler had been asked to advise

on the layout of Fair Park, the fairgrounds that the City of Dallas had acquired in 1904

in an effort to revitalize and improve the State Fair of Texas. Kessler's

involvement with Fair Park had been fostered by George B. Dealey, Publisher of

the Dallas Morning News, who had observed

Kessler's work firsthand at the St. Louis World's Fair in 1904. Dealey and his

newspaper became heavily involved in promoting Kessler's work, particularly his

concept for a union passenger station to be located downtown.

Railroads figured prominently in the Kessler Plan,

including a Union Passenger

Terminal at the west end of downtown, the removal of the T&P tracks from Pacific Ave., and

a new "belt

line" track around Dallas. The belt line would facilitate rerouting

SP's north/south trains to pass east of downtown, and the T&P's

east/west trains to pass south of downtown. The belt line and the Pacific Ave.

track removal were intended to reduce train traffic through downtown, a safety

hazard that was getting worse as both the

population and the train counts increased. Much of the Kessler Plan was implemented over a long

period of time, and the plan was amended to include a levee system for the

Trinity River floodway and a re-routing of the main river channel away from downtown.

Seven neighborhoods in Oak

Cliff carry the name "Kessler" in honor of his work.

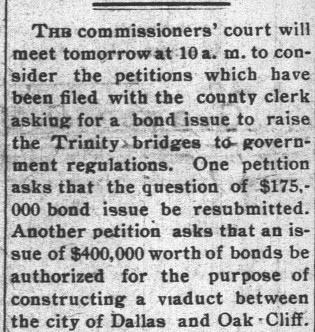

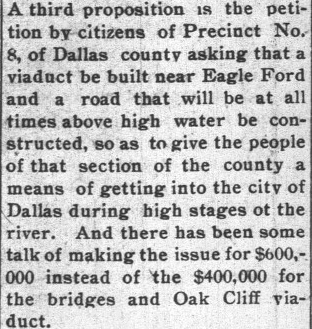

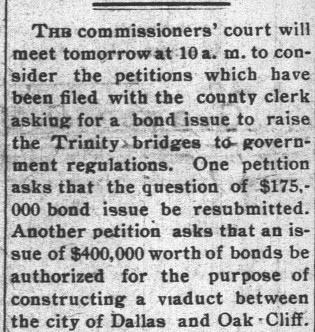

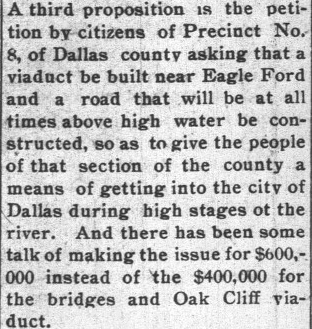

Right: (Lancaster Herald,

June 18, 1909) A new Dallas - Oak Cliff viaduct that could withstand

another Great Flood was needed quickly, so Dallas County commissioners

wasted no time in formulating a plan. Residents of the town of

Lancaster in far

southern Dallas County followed the developments closely through the

local newspaper, the Lancaster Herald.

Like Oak Cliff, Lancaster was on the "other side" of the Trinity River.

Rather than having to go northwest to Oak Cliff to cross the river,

Lancaster citizens wanted a bridge at nearby Millers Crossing (a.k.a.

Millers Ferry, the namesake for what is

now Union Pacific's Miller Yard.)

Barely a year past the Great Flood, Dallas County commissioners were

meeting for a vote to issue bonds for the viaduct and to "raise the Trinity bridges to government regulations." The

U. S. War Department had decided that the Trinity River might someday

need to be navigable for ocean-going vessels from the Gulf of Mexico

(and Dallas is still waiting for the first one to arrive), so they

required all new bridges over the Trinity River at downtown Dallas and downstream

thereof to have 90

feet of horizontal clearance and be 60 feet

above the nominal water level (the Great Flood had been measured

at 52 feet.) The bond issue was set at $600,000; many

citizens were opposed to it, convinced that the work could be done

substantially cheaper, hence there must be graft and corruption behind

it. Nonetheless, Dallas County voters approved the bond issue and the

project was completed sucessfully. |

|

|

Above Left: The 1911 photos at the top of the page show

the southwest long wall of Tower 57 with the visible staircase, but this photo (from

the Layland Museum collection in Cleburne) shows the opposite long wall which faced

northeast. The June, 1908 edition of The Signal

Engineer states that the flood put Tower 57 "under water...for two

weeks" with substantial damage. This photo shows scaffolding around the base

of the tower as it was being augmented with a new structure to

raise its height so that operators would have a clear view of the rails to the south

over the finished viaduct. Whether this image shows the tower at its final

height has not been determined, but the tower is substantially elevated given that the

bottom floor would originally have been accessible from ground level.

Above Right:

This photo of Tower 57 is from

the book

Dallas

Rediscovered: A Photographic Chronicle of Urban Expansion, 1870-1925 by

William L. McDonald (Dallas Historical Society, 1978, hat tip, Bill

Bentsen.) Multiple vehicles on the roadway imply the photo was taken after

February, 1912, yet the tower appears to lack its finished roof, which is fully

intact in the other photos. The tower exterior appears dark, not the light color

in the other photos which was probably the standard Santa Fe Yellow paint scheme. Even

more mysterious, the overall shape of the tower does not appear to be identical

in both photos. The footprint of the tower in the

Dallas Rediscovered image looks to be a bit closer to a square in

contrast to

the Layland Museum photo and the 1911 photos where the long wall is at least twice as wide

as the short wall. Although the stovepipe and the middle window on

the short side provide commonality across both photos, they are the only

elements that do so. Otherwise, the towers look somewhat different.

It is not

surprising to find that the dichotomy of Tower 57's photographic appearance was

reflected in the picture postcards of the era. Offset printing presses

became commercially available c.1905, leading to an explosion of mass-produced,

color

postcards derived from photographs that were retouched and colorized by hand

before being sent to the presses. These two cards show generally the same view

of Tower 57, yet the

structures

are obviously different. The card above left

shows the black stovepipe on the northeast long wall, and under magnification, the

two windows on that wall are located the same as they are in the Layland Museum

photo. There are no windows on the new lower story that was added to raise the

tower's height. This suggests that the original source photograph showed Tower 57

as seen in the Layland Museum photo,

with the exception of a much darker exterior color.

In significant contrast, the card above right

omits the stovepipe and adds symmetrically positioned windows on each floor,

similar to neither of the photos above. The outer walls are not Santa Fe

Yellow; the color could suggest a brick exterior. The roof color is different,

but the roofline is similar. The roof has no apparent protrusions, but a

stovepipe penetrating the roof on the opposite side might not be visible from

this angle. Note also that a man is standing on the viaduct at the top of a stairway;

this stairway still exists. Besides adding color, the idea behind the retouching process was to make

minor image adjustments, hence it would seem to be completely unwarranted to redraw

the tower from scratch with features that did not exist (not that the

postcard-buying public would notice or care.) The basis for the tower's visual

appearance in this postcard remains undetermined.

Below Left: This postcard has

a view from the viaduct that

looks back toward Dallas showing the top of the tower and a portion of its

southwest side. The staircase landing for the operations room is near the left edge of

the tower, as it was in the 1911 photos at the top of the page. Although the

window below the staircase is more obvious due the the contrast with the

exterior color, it is also present in the 1911 photos. Even with the increased height

of the tower, the width of the viaduct leaves the operators' track visibility to

the south questionable.

Below Right: This postcard adds little to the discussion

since only the operations floor is visible, but it does

reinforce the idea that Dallas' "world record" viaduct was a popular postcard

topic.

Below: These two Google Street Views from May, 2022 show

the Houston St. Viaduct near the 47-degree curve. In the southwest view (below

left), the red railing partly visible in the foreground is

attached to the staircase where the man is standing on the north side of the

viaduct (upper right postcard.) Looking northeast (below right),

the view is similar to the postcard directly above it. Note that streetcar rails

have been added to the Houston St. roadway.

Perhaps the postcard (upper right) showing a closer view of the tower with four

symmetrical windows and no stovepipe was simply the result of a retouching

process gone awry. The other three postcards are generally consistent with the

1911 photos and the Layland Museum photo. This does not explain, however, the apparent

differences in the Dallas Rediscovered

photograph. Perhaps those can be attributed to a roof replacement project,

darker paint, optical illusion and poor image quality. Other than raising its

height, no evidence has

surfaced to indicate that Tower 57 was ever rebuilt during or after the

viaduct's construction, and the timing weighs against it. The Dallas - Oak Cliff

viaduct opened in February, 1912, and one month later, the Union Terminal Co.

was chartered to build Dallas Union Terminal (as it

was originally called.)

With a plan underway by March, 1912 leading to the retirement

of Tower 57 in 1916 (an outcome that surely would have been grasped at the

outset), it seems unlikely that the tower was rebuilt in the interim.

Although execution of the union station plan began in March, 1912,

establishing the plan had been exceedingly difficult. Dallas

city and county officials, railroad executives, and local

business leaders simply could not reach agreement on where a union depot would

be located nor how it would be funded or operated. This had been a

long-festering issue dating back to the DTR&UD's initial efforts under its

charter granted in 1895. A new state law passed in 1909 authorized RCT to order

cities to build union depots when necessary for the convenience of the traveling

public, and Dallas was at the top of the list. RCT issued an order on December

2, 1909 requiring the City of Dallas to construct a union passenger terminal,

replacing five separate stations. When the City and the railroads failed to

submit a responsive plan to RCT before the deadline of May 1, 1910, RCT asked

the Texas Attorney General to file a lawsuit (but whether he actually did so is

undetermined.) Kessler's larger planning effort

for the Chamber of Commerce was already underway, so the City requested his participation in

developing a detailed plan for a union passenger terminal. A major conference of railroad executives,

government officials and local business leaders was held in Dallas on February 8,

1911, but it still took another year of meetings to create the final plan and

charter the Union Terminal Co.

To the public, the focus of the Union

Terminal Co. was the design and construction of Dallas Union Station, but the

company also had to redesign the track layout in the west end of downtown so

that all of the railroads could access the new station. Due to the location of

the T&P and Rock Island bridges over the Trinity, considerable freight traffic

would also pass Union Station (as it does so today.) This freight traffic would

increase when T&P trains were routed south of downtown in later years on the new

belt line because they still had to return to the west end of downtown to cross

the T&P bridge. Looking ahead to Dallas' long term growth and anticipated increases in train

counts, the

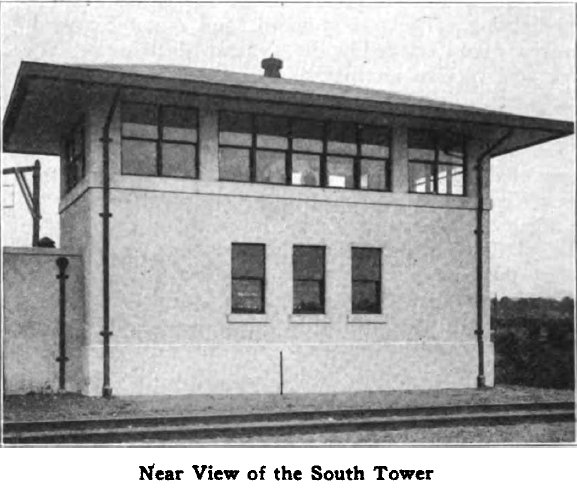

decision was made to replace Tower 57 with two interlocking towers to share the control responsibilities for the new track

arrangement. The buildings were

identical in architecture, and were known to the company as North Tower and

South Tower. RCT designated them Tower 106 and Tower 107, respectively, and both are still standing.

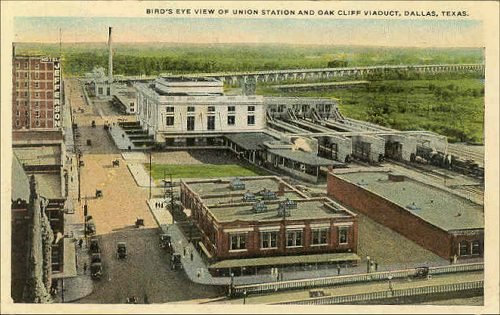

Union Terminal

Co. had also obtained a

state railroad charter so that it could build and operate tracks as necessary (and

sign trackage rights agreements) to facilitate a continuing mission to provide railcar

switching services among the eight steam railroads that comprised equal shares

of the company's ownership. These railroads were the Santa Fe,

Rock Island, Southern Pacific (through its H&TC subsidiary), Texas & Pacific, the Missouri, Kansas & Texas

("Katy"), the St. Louis San Francisco ("Frisco), the St. Louis Southwestern ("Cotton

Belt") and the Trinity & Brazos Valley. By the time Union Station

opened, the company had laid five miles of track.

|

Left and Below: Dallas Union Station opened

officially on October 14, 1916, designed for a daily capacity of 50,000

passengers and 80 trains. As Kessler had envisioned, a small park (now Ferris Plaza, managed by the Dallas Parks & Recreation Department) was established

directly across Houston St. from Union Station to welcome arriving visitors. The interurban added a stop at the

park so that passengers could

transfer easily to and from the steam railroads. (photo, Wikimedia Commons)

|

|

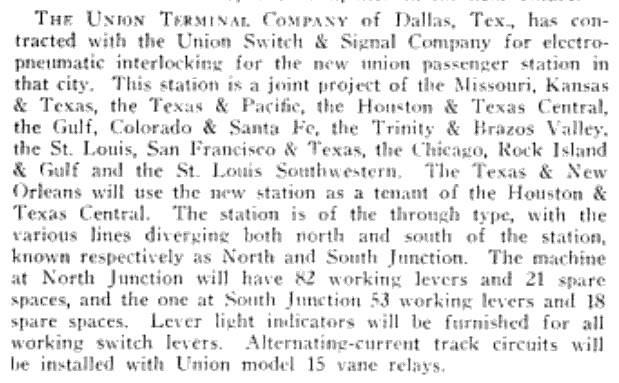

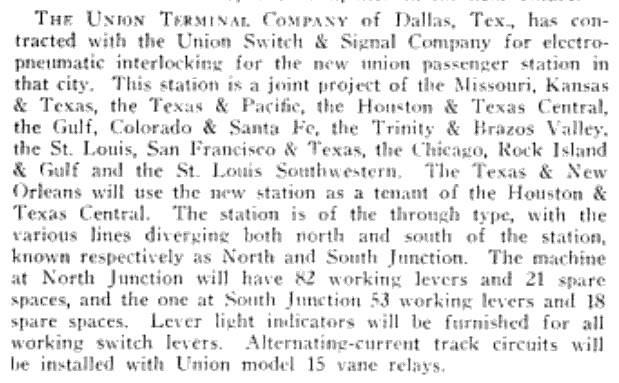

Left: The Railway Age

Gazette of September 10, 1915 carried this brief news item announcing

that a Union Terminal Company contract had been awarded to Union Switch & Signal

Co. for two interlocking machines to control traffic in the vicinity of

the "new union passenger station..." Union Station would open thirteen months

later. It notes that the Texas & New Orleans (T&NO) Railroad would use Union

Station as a "tenant of the Houston & Texas Central". Both T&NO and H&TC were

owned by Southern Pacific (SP). The H&TC line was the first railroad in Dallas,

passing through in 1872 building north to Denison to complete its main line from

Houston. The T&NO line ran from Dallas southeast to Beaumont via Kaufman,

Jacksonville and Lufkin. In 1927, SP would make T&NO its principal operating

company for Texas and Louisiana, leasing the H&TC and other SP railroads in

Texas to the T&NO. In 1934, this was converted to a merger; the H&TC ceased to

exist as it was consolidated into the T&NO. |

Above: Two weeks before Union

Station opened, the new interlocking design and track layout became fully

operational. A comprehensive article about the two new

interlocking towers was written by a Santa Fe signal engineer and published in the

February, 1917 edition of Railway Signal Engineer.

The article describes the interlockers as electro-pneumatic plants "...placed in service on the morning of October 1,

1916...", a rather definitive point in time. Tower 57 was officially

closed; RCT documentation at DeGolyer Library gives "August, 1916" as the

retirement date, but there was likely a transition period since the new towers

were not scheduled to begin operation until October. RCT's annual published list

of active interlockers dated December 31, 1927 changed the Tower 106

commissioning date to be April 26, 1916, but Tower 107's commissioning date

remained the same, "October, 1916" which had also been used for Tower 106 in all

previous lists. This might indicate that a review of Tower 106 records

determined that it had been approved for operation more than five months

earlier, perhaps for test purposes given the overall complexity of the design.

Tower 106 would likely have been tested first since it should have had less

control overlap with Tower 57, which was still operational in April, 1916 and

located very close to Tower 107.

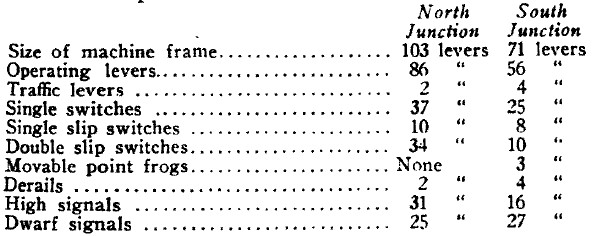

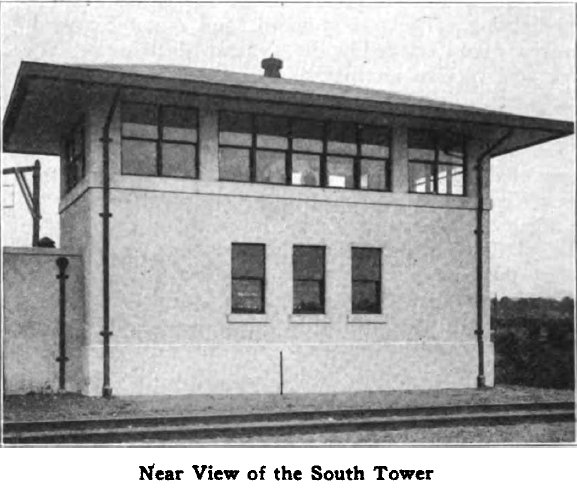

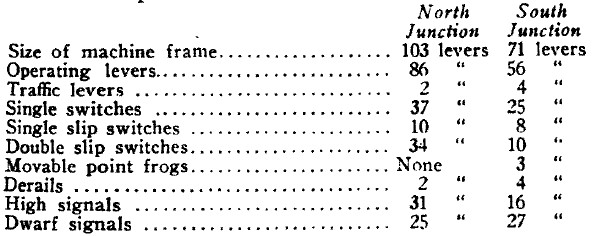

Below Left: Tower 107 as it appeared in the article;

Below Right: summary of the

interlocking plants as printed in the article

Above: Sometime in the late

1930s or early 1940s, railroad executive John W. Barriger III snapped this photo

of Tower 106 from the rear platform of his business car as his train was heading

south into Union Station. Below:

Barriger took this photo of Tower 107 as his train continued south out of Union

Station. The tower was adjacent to an interurban bridge (note overhead wires

barely visible.) The staircase in the background provides pedestrians with

access to the south side of the Houston St. Viaduct near where it makes its

47-degree turn. Were Tower 57 still standing, it would have been on the far

side of the viaduct, visible through the gap to the right

of the leftmost interurban bridge stanchion.

Above: The levee system for

the Trinity River proved successful in mitigating damage from Trinity River

floods; the date of this one is unknown, probably the 1940s, perhaps the major

flood of 1949. Tower 106 is prominent near the center of the image which faces

southwest. Note the curved trestle needed to carry the T&P's southwest

connecting track which led to Union Station and the Dallas Belt Line. It carried

all T&P trains except switchers since the former main line tracks on Pacific

Ave. had been relegated to industry access. The river had been straightened in

the late 1920s in conjunction with levee construction, but floods would spill

over to fill various meanders that remained in the flood plain, including the

former main channel of the Trinity River, visible here at the edge of downtown.

Below: This image is farther

south with a view of Tower 107 at left beside the interurban bridge -- note the

2-car interurban that is heading into downtown. Union Station is along the right

edge, and a nearby wye bridge track extends out into the floodplain. The Houston

St. Viaduct is visible carrying a steady stream of cars. (both images from a

single aerial photo by Lloyd M. Long, courtesy Foscue Map Collection, SMU

Libraries)

|

Left:

On January 1, 1938, this photo of a Burlington-Rock Island passenger

train was taken by Otto Perry shortly after the train had passed Tower

107 as it headed south to Houston. (Denver Public Library collection)

Right: Tower

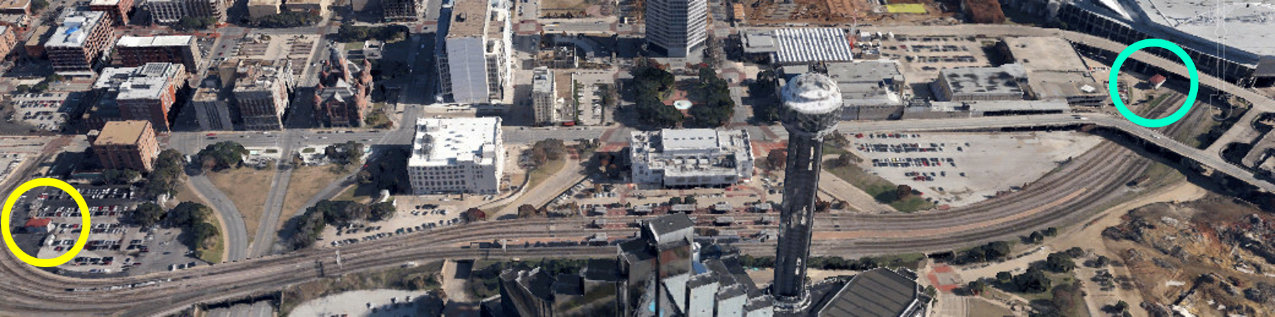

107 is about 100 yards southeast of the location where Tower 57 stood. |

|

Above Left: This May, 2022 Google Street View image of Tower 106

was captured looking west-southwest from the intersection of Houston St. and Pacific Ave. While the T&P tracks

were removed from Pacific Ave. as part of the Kessler Plan, DART tracks were

added on Pacific Ave. in the 1990s so that the DART light rail system could access

Union Station. Above Right: This Google Earth image show that Tower 106 sits in

a parking lot behind the Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza. The museum

documents the assassination of President John Kennedy in 1963. The Warren

Commission Report produced by the investigation states that an "employee of the Union Terminal Co., Lee E. Bowers,

Jr., was at work in a railroad tower about 14 feet above the tracks to the north

of the railroad bridge and northwest of the corner of Elm and Houston,

approximately 50 yards from the back of the Depository. ... In the railroad

tower, Bowers heard three shots, which sounded as though they came either from

the Depository Building or near the mouth of the Triple Underpass. Prior to

November 22, 1963, Bowers had noted the similarity of the sounds coming from the

vicinity of the Depository and those from the Triple Underpass, which he

attributed to 'a reverberation which takes place from either location.'

" Tower 106 is now owned by the Sixth Floor Musuem.

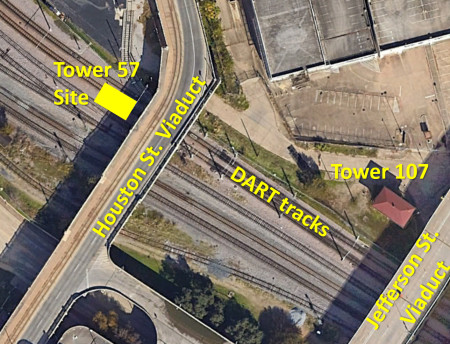

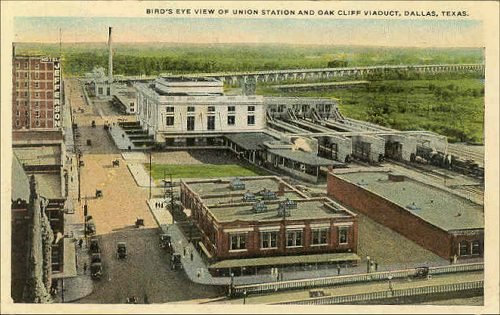

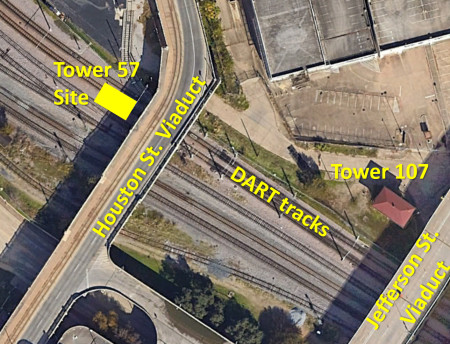

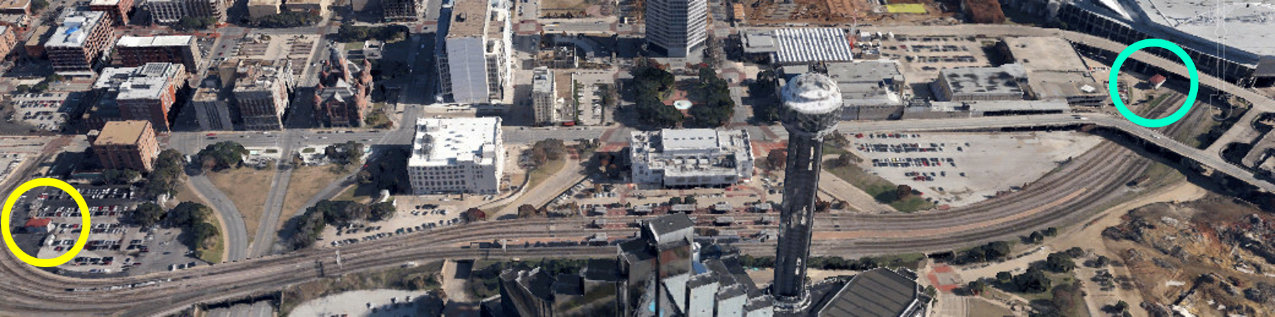

Above: This bird's eye view of

Union Station faces east, showing both Tower 106 (yellow circle) and Tower 107

(blue circle) with tracks for passenger, freight and light rail trains passing

the station and both towers. Ferris Plaza is visible as the green space east of

Union Station across Houston St. Across the tracks from Union Station, Reunion

Tower stands adjacent to the Hyatt Regency Hotel. South of Union Station, Houston St.

slowly rises and makes the 47-degree turn to the southwest onto the Houston St.

Viaduct. Tower 57 was located in the shadow beneath and along the near side of the

viaduct. Note that the tracks proceed past Tower 107, go under the Jefferson St.

Viaduct, and then ... disappear into a building?? Yes. All of the tracks pass through a

portion of the Dallas Convention Center where a DART station is located. (Google

Earth, 2013)

Below Left: Judging by the three air conditioning units on the

back side of Tower 107, DART may have employees as well as electronic equipment

housed in the building. Below Right:

Facing northwest, the tracks enter the east side of the Dallas Convention Center

for a short (415 ft.) transition through the building toward Union Station.