Texas Railroad History - Tower 192 - Fort Worth (Purina,

Dalwor & 6th St. Junctions)

A Large Wye Junction of the Chicago, Rock

Island & Gulf Railway near Downtown Ft. Worth

|

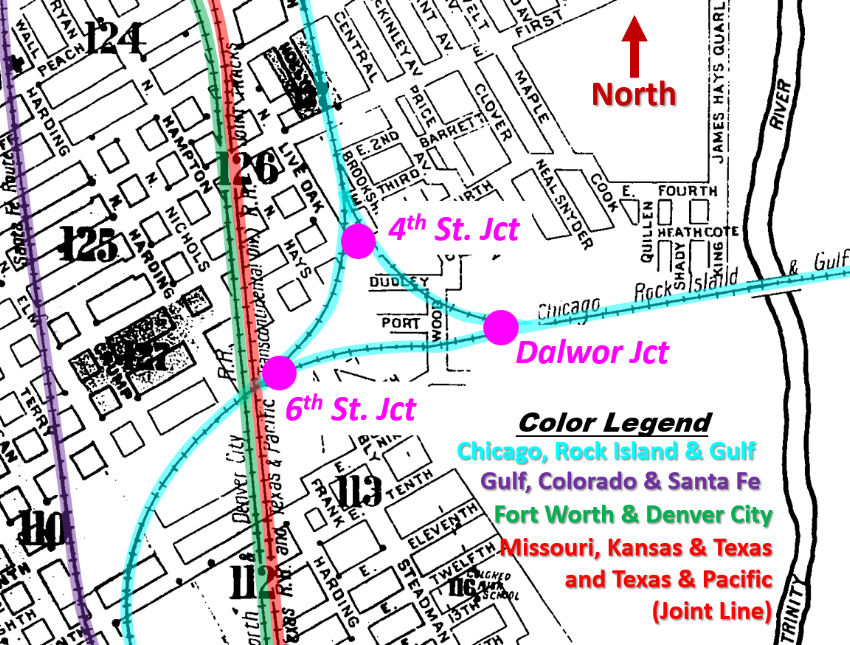

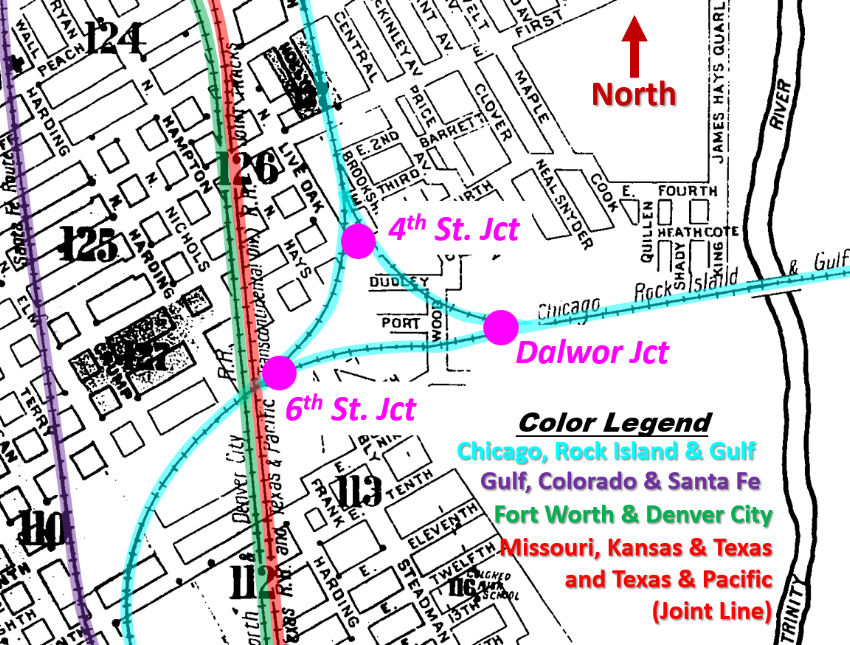

Left: This

index from the 1910 Sanborn Fire Insurance Co. map of Fort Worth has

been annotated to highlight three junctions of the Chicago, Rock Island &

Gulf (CRI&G) tracks controlled by the Tower 192 interlocker. The

junctions are less than a mile northeast of downtown Fort Worth

and they remain active today. The interlocker archives

of the Railroad Commission of Texas (RCT) stored at DeGolyer Library,

Southern Methodist University, have a Tower 192 folder labeled "4th St.

Jct., 6th St. Jct. and Dalwor Jct.", clearly identifying this area

as the focal point of this interlocker.

The Tower 192

interlocker was authorized for service by RCT on August 26, 1946 to

control all three junctions. It was an automatic plant with remote

controls located in the CRI&G dispatcher's office. By May, 1947, 4th St.

Junction had been renamed "Purina Junction" by Rock Island officials,

due to its proximity to a large Ralston Purina Co. plant that was a

major Rock Island customer.

Although not

readily apparent from the map, the north/south tracks immediately west

of 6th St. Junction cross over the CRI&G tracks on a bridge. When

this map was drawn, they

belonged to the Fort Worth & Denver City Railroad, and the Missouri, Kansas & Texas and Texas & Pacific railroads

(joint track.) Today they belong to

successor railroads Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) and Union

Pacific (UP), respectively. |

For compliance with Texas' railroad ownership laws, the

Chicago, Rock Island & Texas (CRI&T) Railway was chartered as a Texas-based

subsidiary of the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific ("Rock Island") Railroad to own

tracks that were being extended south from

Oklahoma in 1892. By charter, the original target was Weatherford, 27 miles west of Fort Worth.

CRI&T rails crossed the Red River north of Ringgold and proceeded generally

south through Bowie to Bridgeport on a direct

heading to Weatherford 32 miles farther south. The line to Weatherford

was never completed; instead, the charter was amended in 1893 to authorize

construction to Fort Worth and

Dallas. The tracks out of Bridgeport went

southeast to Fort Worth, reaching there on August 1, 1893.

|

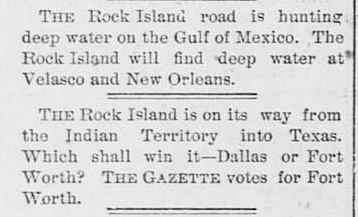

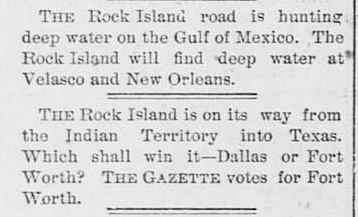

Left:

Cheerleading for their community (one of the prime responsibilities of

early Texas newspapers) has the Fort

Worth Gazette of March 5, 1892 speculating on the Rock

Island's plans.

Right:

By March 24th, the Fort Worth Gazette

had begun reporting on Fort Worth businesses hired to perform grading

work for the Rock Island. Bowie is about sixty miles northwest of Fort

Worth, so the Rock Island was definitely coming to Texas, but the true

destination was unknown. The newspaper comments that the route "...can't

long be kept from the public." The charter bill had already been passed

into law, but for competitive reasons, railroads didn't always specify

their true plans in the charter, preferring to amend it later

once their construction was close enough to facilitate a quick

redirection. Weatherford was the official

destination, but it's plausible that they never intended to build there. |

|

Why was

Weatherford the initial target? In his book A History

of the Texas Railroads (St. Clair Publishing 1941), S. G. Reed, the dean

of Texas railroad historians, acknowledges the plan to build to Weatherford and

the subsequent decision to redirect the line to Fort Worth, but he has no

comment on the underlying rationale for either decision. In the early 1890s,

Fort Worth was about five or six times larger in population than Weatherford.

So, if it was legitimate,

the idea to bypass Fort Worth would need to have been based on some benefit to be

realized by reaching Weatherford (which obviously did not relate to passenger

service, given the massive disparity in population.) Two major railroad

connections were available at Weatherford: the Texas & Pacific (T&P) east/west

main line to Ft. Worth and El Paso, and a branch

line of the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe (GC&SF) Railway to

Cleburne from which its main line extended south to

Houston and Galveston.

Access to the Gulf coast for export of grain and other agricultural products

from states served by Rock Island was certainly a prime objective, so a

connection with the GC&SF at Weatherford would potentially have offered faster

service to Galveston as opposed to routing freight through the complex rail

network in Fort Worth (which the GC&SF main line also served.) Yet, the GC&SF

parent company, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe, was a direct competitor of Rock

Island for much of the agricultural freight that would be coming from the Plains states.

It seems more likely that

Weatherford was a misdirection by Rock Island for both competitive and

land-purchase reasons, i.e. just plausible enough that competitors might believe

it. Building to Bowie and Bridgeport aligned with construction to Weatherford,

but left Rock Island close enough for a sudden redirection to Fort Worth. Fort

Worth and Dallas were too large to ignore, but announcing that plan in their

initial charter would have given other railroads a head start on countering it

(for example, by new construction on the north side of Ft. Worth to grab the

best rights-of-way.) Also, Rock Island wanted to procure land in its path to be

sold at a profit when prices rose due to the arrival of the railroad. Allowing

the entire route to be precisely and publicly known empowered the land

speculators to get there first, raising land acquisition costs.

Having reached Fort Worth, Rock

Island remained interested in building a line to the Gulf but also wanted to

serve Dallas.

In 1902, they sought

approval to build from Ft. Worth to Galveston via Dallas under the name of the

Chicago, Rock Island & Gulf (CRI&G) Railroad. The CRI&G was also authorized by

its charter (issued May 13, 1902) to absorb the other three Rock Island

subsidiaries in Texas (the CRI&T and two subsidiaries in the Texas Panhandle.)

The CRI&G tracks from Fort Worth to Dallas were laid in 1903, but it was the extension

beyond Dallas to

Houston and Galveston that created the most consternation for the other railroads in Texas.

It was considered a serious threat, and railroads conducted in-depth negotiations with Rock Island about potential arrangements

to mitigate a Rock Island takeover of Texas railroading. The International &

Great Northern (I&GN) offered to sell its recently completed line between Fort

Worth and Houston, but Rock Island wasn't interested. Southern Pacific (SP) was

particularly concerned; their Houston & Texas Central (H&TC) subsidiary had a

route from Ft. Worth to Houston (via the main line at Garrett) and was

undoubtedly carrying most (or perhaps all) of

Rock Island's loads destined for the Gulf coast. SP also learned that Rock

Island had been surveying a route between Dallas and Houston that was shorter,

with fewer curves and lower grades than the H&TC line. Other than the I&GN route

(which was poorly constructed and less direct), the sole alternative to SP from

Ft. Worth to the Gulf was Santa Fe's main line. But as direct competitors with

Rock Island in many of the areas from which these loads originated, they were

unlikely to have offered favorable rates and divisions.

Eventually, SP

and Rock Island agreed

to a massive and complex plan involving split ownership of three SP component

railroads in Texas: the H&TC, the Houston East & West Texas, which ran from

Shreveport to Houston, and a new SP subsidiary that would be created to own the

Texas & New Orleans line from Dallas to Sabine Pass via Beaumont. In addition to

owning half of each of these railroads, Rock Island would be allowed to choose the President of each railroad.

Trackage rights and other service agreements fleshed out the remainder of the

contract between SP and Rock Island, which was promptly submitted to RCT. This would have dramatically

changed the evolution of the rail network in Texas, but RCT refused to approve

the plan.

Ultimately, the CRI&G's tracks were not extended to Galveston directly.

Instead, Rock Island became a 50% owner of the Trinity & Brazos Valley

(T&BV) Railway

which eventually offered service to Houston and

Galveston from both Dallas and Ft. Worth, having built on the shorter, low grade

right-of-way that had worried SP. In a fit of spite, SP responded by building

the Mexia - Nelleva Cutoff to compete directly with the new line, paralleling

the T&BV tracks a few yards to the west for 42 miles! ... which

did not work out well for either railroad.

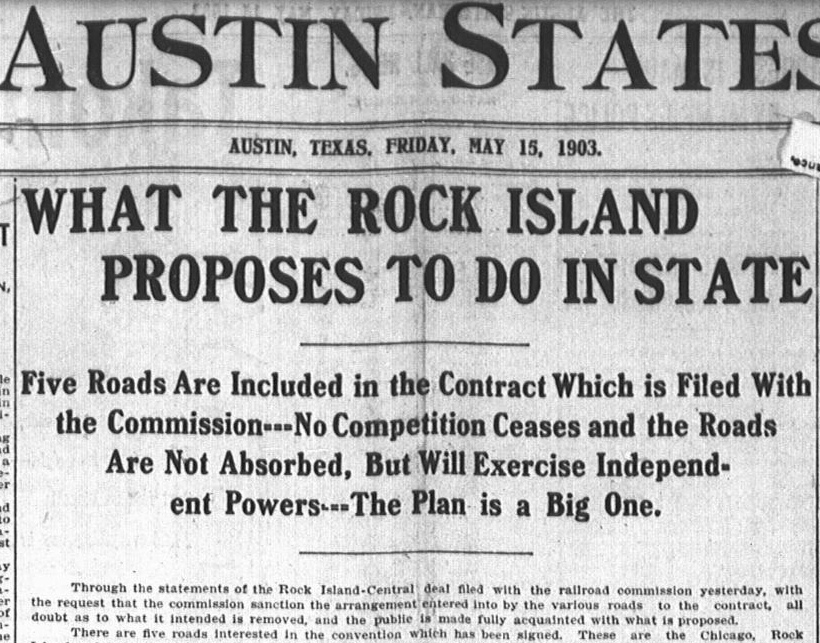

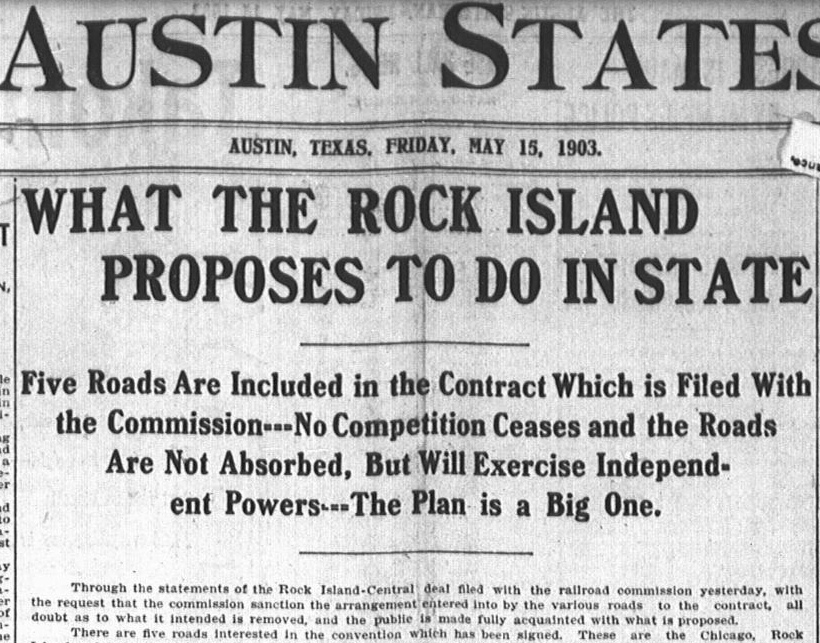

Above: The "Rock Island -

Central deal" (Central, as in "Houston & Texas Central") was front page news on

May 15, 1903 in the Austin Statesman.

The article goes on to discuss the proposed arrangement that had been submitted

to RCT the previous day. It would have radically altered railroad

development in Texas, but the Commission voted 2 - 1 against approval. Within a

year, Rock Island had adopted an aggressive plan to compete, rather than

cooperate, with SP.

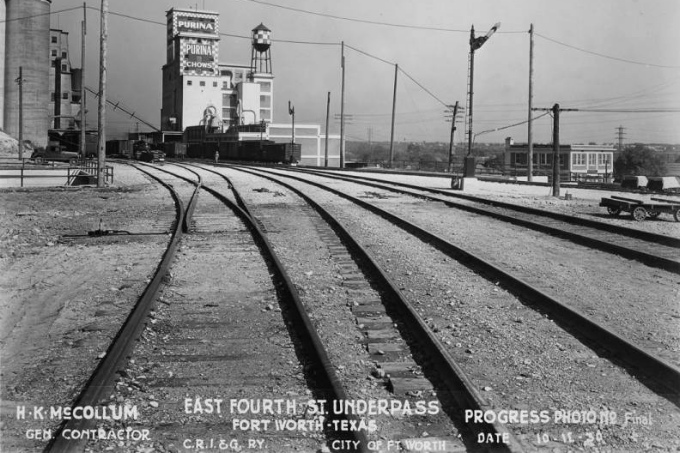

Intent on starting toward the Gulf, the CRI&G

initiated construction to Dallas in 1903, departing Fort Worth from Rock Island's existing tracks between 4th St. and 6th St. The decision was

made to create a triangular junction that could also serve as a wye. This track

arrangement was in place by the end of 1903, but the junctions were not

interlocked. In 1917, the Purina feed mill was built immediately north of the

4th St. junction, eventually incorporating some existing buildings into a larger

complex. In 1930, the City of Fort Worth began construction of a lengthy

underpass to eliminate the 4th St. grade crossing of two legs of the wye.

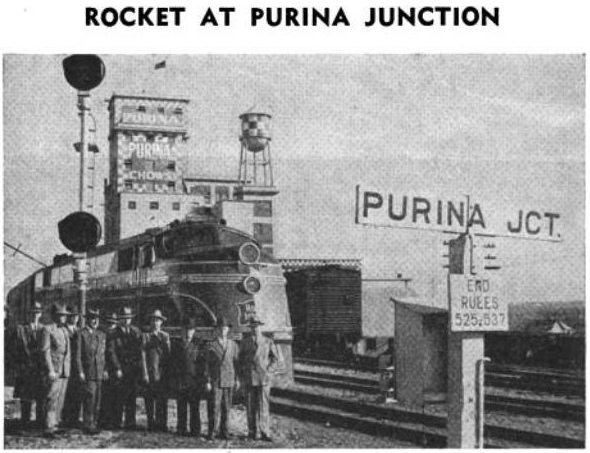

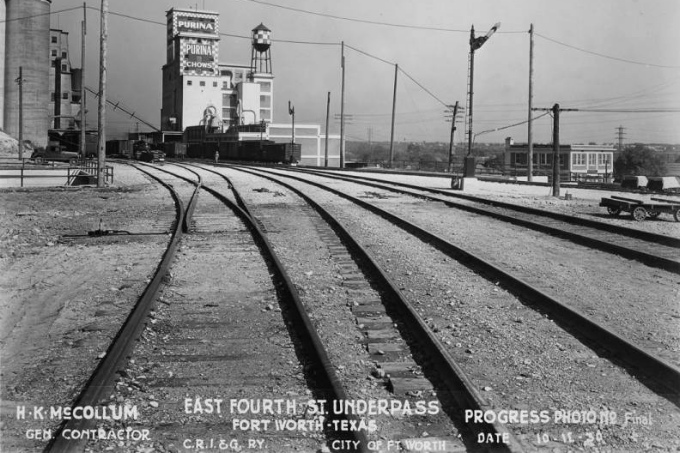

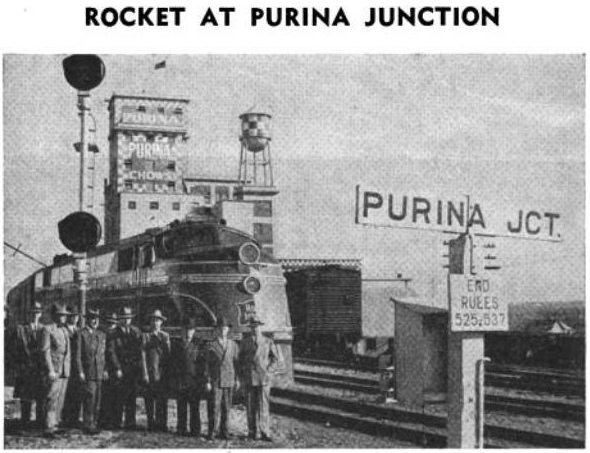

Above Left: Numerous photos of

the 4th St. underpass construction project were taken, including this one

looking back to the north toward the Purina feed mill from 4th St. Junction.

(Ft. Worth Public Library collection) Above

Right: This photo appeared in the

Rock Island Lines News Digest of May, 1947.

The accompanying article explains that to honor their major customer, Rock

Island had officially renamed 4th St. Junction to be Purina Junction. The group

is standing in front of the Twin Star Rocket passenger train (Minneapolis to

Houston via Ft. Worth) which had only been operating for slightly more than two

years. Below: Facing

northeast, the 4th St. entrance to the Purina mill remains adjacent to the underpass. (Google Street View,

October 2021)

|

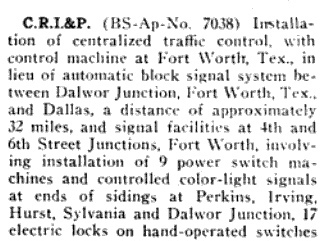

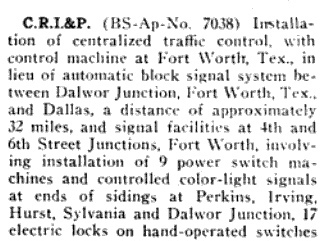

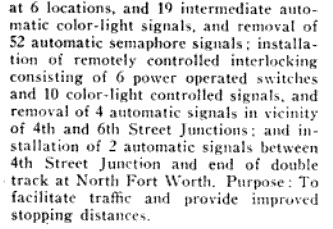

Left and

Right: The February, 1945 issue of

Railway Signaling

describes Rock Island's submission to the Interstate Commerce Commission

(ICC)

which proposed to improve and interlock operations at 4th St., 6th St.

and Dalwor Junctions. To some undetermined extent, one or more of these

junctions had been manned for the purpose of conveying train orders and

setting semaphore signals. The December, 1912 edition of

The Railroad Telegrapher, a

magazine produced by the telegrapher's union, mentions that a member is

currently "working extra at Dalwor Junction." The ICC approved Rock

Island's submission, and Tower 192 was authorized for operation by RCT

on August 26, 1946. |

|

Above: satellite view of

Purina Junction and the 4th St. underpass (Google Earth)

Below Left: When Rock Island

went bankrupt in 1980, signs such as this one near the Purina Junction cabin

began to pop up. (Ronnie Patterson collection)

Below Right: Eastbound on 4th St., the underpass still

shows the faint herald of the Rock Island. (Google Street View)

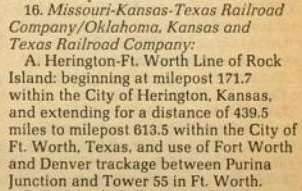

Left:

In March, 1980, Rock Island went into bankruptcy and ceased operations. The

Federal Register

on June 30, 1980 published an announcement that the ICC had granted permission

for the Oklahoma, Kansas & Texas (OKT) Railroad, a new subsidiary of the

Missouri - Kansas - Texas Railroad, to operate over the Rock Island main line

between Herington, KS and Fort Worth. Rock Island tracks were gradually sold off

by the Bankruptcy Trustee.

Left:

In March, 1980, Rock Island went into bankruptcy and ceased operations. The

Federal Register

on June 30, 1980 published an announcement that the ICC had granted permission

for the Oklahoma, Kansas & Texas (OKT) Railroad, a new subsidiary of the

Missouri - Kansas - Texas Railroad, to operate over the Rock Island main line

between Herington, KS and Fort Worth. Rock Island tracks were gradually sold off

by the Bankruptcy Trustee.

All three junctions

and associated tracks that were controlled by Tower 192 remain operational

today. The former Rock Island tracks between Dallas and Fort Worth are now used

by the Trinity Railway Express to operate commuter rail service between downtown

Ft. Worth and downtown Dallas.

Above: current 3-D views of

Dalwor Jct. (left) and 6th St. Jct. (right)

simulated by Google Maps Below Left:

current 3-D view of Purina Jct. simulated by Google Maps

Below Right: January, 2020

Google Street View of Purina Jct. looking south from 1st. Street.