Texas Railroad History - Towers 12 and 104 - Houston

(Blodgett) and Bellaire

Two Crossings of the Southern Pacific

Railroad by the San Antonio and Aransas Pass Railway in Houston

|

The post-Civil War Reconstruction era in Texas

officially lasted until March, 1870 when the state was formally

readmitted to the Union. By then, the economy had begun to recover

sufficiently for investors to consider financing Texas railroad

expansion, particularly in the coastal region near Houston. By the

latter 1870s, it was clear that Houston's growth would eventually

position it to challenge Galveston's status as the leading (and most

populous) city of Texas. Houston had been founded along the banks of

Buffalo Bayou, a transportation artery that despite limited depth had

helped foster Houston's growth since the 1830s.

Track-laying for the first railroad in Texas, the Buffalo Bayou,

Brazos and Colorado (BBB&C) Railway, began in 1853 at

Harrisburg, a port on Buffalo Bayou

where the water was usually deep enough to support

steamboats year round. Building west, the BBB&C passed several miles south of Houston

and stopped at the Colorado River in 1860. Under new ownership, the BBB&C became the Galveston, Harrisburg & San Antonio

(GH&SA) Railway, and it reached San Antonio

in 1877. To serve Houston, the GH&SA

negotiated with the International & Great Northern (I&GN) to use the Columbia Tap

rail line from Pierce

Junction, six miles south of downtown.

The Southern Pacific

(SP) Railroad was building to El Paso

from the west coast and wanted to continue across Texas to New Orleans.

The GH&SA line to San Antonio fit SP's needs perfectly, so they began negotiating to

extend it from San Antonio to El Paso.

The

GH&SA charter contained an innocuous

provision allowing it to connect with any railroad to the Pacific,

providing legal authority to build the extension. SP agreed

to finance the GH&SA's construction while also convincing them to build

their own line

into Houston, dropping the Columbia Tap rights. SP needed to

own or control all of the tracks along its route to New

Orleans and their debt leverage over the GH&SA gave them effective control.

They leased the GH&SA when the line to El Paso was completed in 1883, and

quickly adopted a

GH&SA marketing term, the Sunset Route, as the name of

their line

from California to New Orleans.

In 1880-81, the GH&SA had built

into Houston along SP's preferred alignment,

departing the main at "Stella", about a thousand feet west of Pierce

Junction,

and paralleling the Columbia Tap north-northeast for 3.6 miles.

The tracks then turned north-northwest for several miles, passed over

Buffalo Bayou on a new bridge, and intersected the Houston & Texas Central (H&TC) Railway at

Chaney

Junction. From there, the GH&SA turned east to connect with the Texas & New

Orleans (T&NO) Railroad which had tracks to New Orleans. The GH&SA also

connected to the H&TC at Chaney Junction to reach a shared passenger depot near downtown.

By 1883, all three of these railroads -- the GH&SA, the H&TC and the

T&NO -- were owned or controlled by SP.

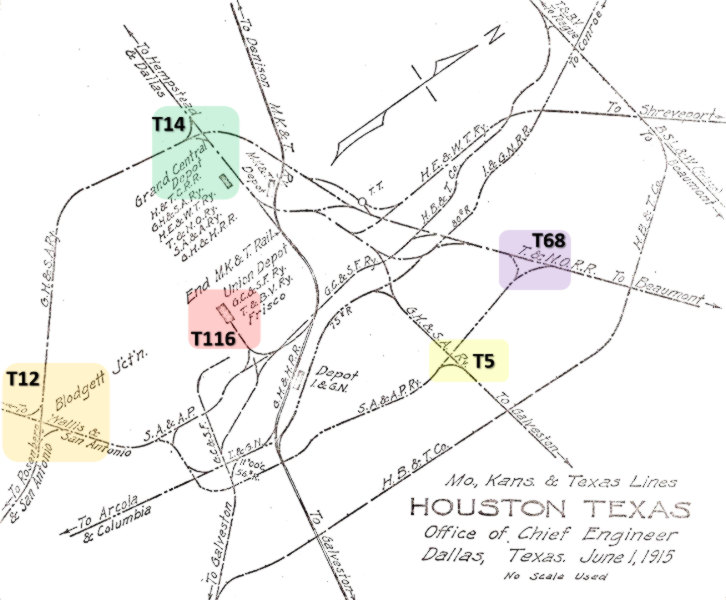

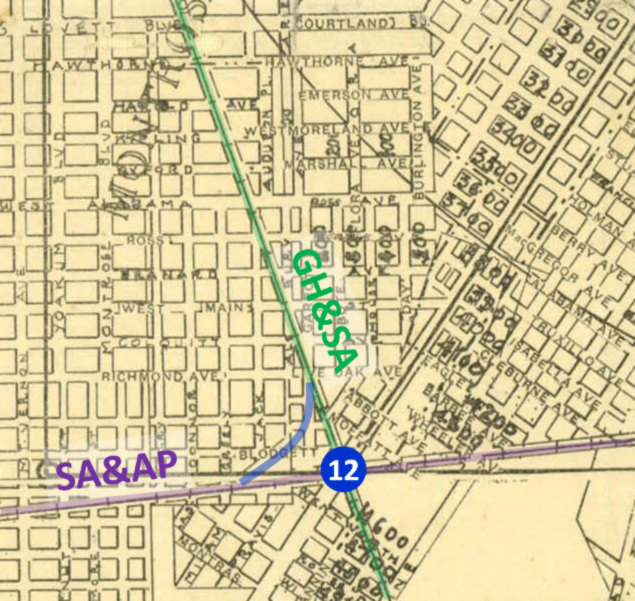

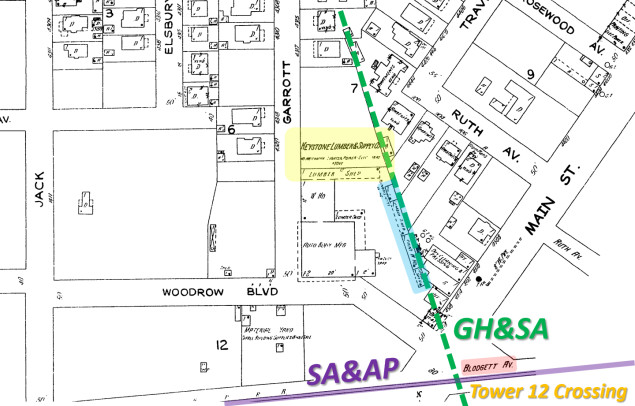

Left:

This annotated Google Map shows rail lines and numbered interlocking

towers on the west side of Houston c.1915 (not all railroads and towers

shown.) The San Antonio & Aransas Pass

Railway had entered Houston in 1888, crossing the GH&SA at Blodgett on

the south edge of the Montrose neighborhood (outlined in red.) In

Montrose, the GH&SA grade was on an embankment 4 to 5 feet above the surrounding land, creating significant

drainage issues that fueled public clamor to have the tracks removed. The

date the red connector was added is undetermined, perhaps 1918 when SP

finished a second

line between Eureka Jct. and West Jct. It presumably replaced an

original connector (green) that was closer to West Jct., as there are

references in legal documents to an "East H&TC Jct." |

The San Antonio & Aransas Pass

(S&AP) Railway had been chartered in 1884 by Uriah Lott with plans to

connect San Antonio with

Aransas Pass, a port on the Gulf of Mexico. By late

1886, tracks had been laid between San Antonio and

Corpus Christi, instead of Aransas Pass. The SA&AP

added other branch lines in south Texas and built into Houston from the west in 1888.

There, it passed along the

south side of downtown and curved northeast to reach depots and a yard built near

Polk street. The SA&AP crossed the GH&SA's Stella - Chaney Junction line

about two miles southwest of downtown, a location eventually known as

"Blodgett". The origin of the Blodgett name is undetermined, but it is

referenced in numerous Houston Post articles as a

geographic location, presumably the name of a

community or neighborhood.

Shortly after reaching Houston, the SA&AP went into

receivership. The bankruptcy court named SA&AP executive B. F. Yoakum

as one of the Receivers. Yoakum, a native Texan, had been working as a railroad land promoter

in 1886 when he was hired by SA&AP

President Uriah Lott to be the railroad's Traffic Manager. Under Lott's

tutelage, Yoakum quickly moved into executive management.

When the receivership ended in 1892, the newly restructured SA&AP was acquired

by SP, and Yoakum moved on to other railroads, eventually becoming the Chairman

of the St. Louis San Francisco Railway and the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific

Railroad.

|

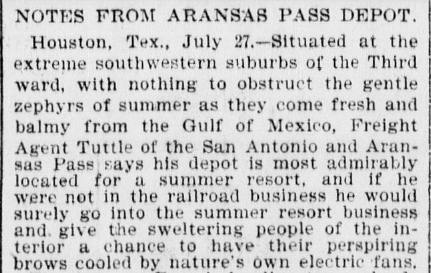

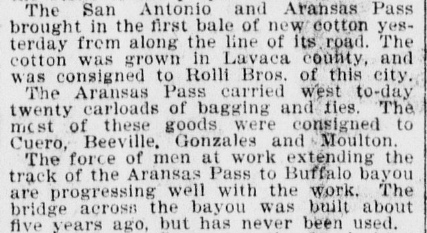

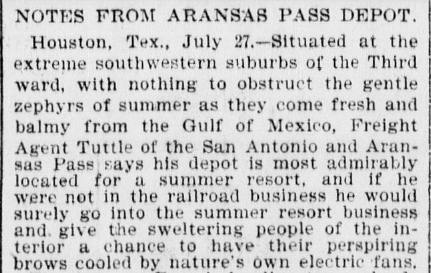

Galveston Daily News, July 28, 1895 |

Left: It's hard to imagine central Houston as a

summer resort in the days before air conditioning, especially compared

to Galveston, where this article was published. Perhaps the heat was

giving the freight agent delusions. The article mentions the SA&AP was

extending its tracks to Buffalo Bayou where a bridge was "...built about

five years ago, but has never been used." This seems doubtful as it

would place construction of the bridge during the SA&AP's receivership.

The bridge may have been built soon after SP acquired the SA&AP in 1892,

but why the delay in laying tracks to the depot?

SP already owned a line from downtown Houston via

Magers to Clinton along the north bank of

Buffalo Bayou. Thus, the bridge would facilitate access to SP's

passenger depot to the east and a connection to the T&NO to the north.

However, no such bridge appears on the 1896 Sanborn map

of Houston. |

Yoakum decided to compete with SP by developing a railroad network between New Orleans and Brownsville, centered on

Houston. In 1903,

eleven years after the SA&AP had been acquired

by SP, the State of Texas sued to demand its divestiture, claiming the acquisition had

violated Texas laws against anti-competitive railroad ownership. When the State

won the lawsuit in 1904, the court ordered SP to divest the SA&AP. SP was

convinced that Yoakum was behind this sudden and mysterious lawsuit, relying on his close

relationships with commissioners of the Railroad Commission of Texas

(RCT). At the time, SP was backing SA&AP efforts to build into

the lower Rio Grande Valley. Was it simply a

coincidence that the State's lawsuit was filed just as Yoakum was also preparing

to build his railroad into the

lower Rio Grande Valley? The end result was that

the SA&AP became independent from SP.

On March 2, 1903, SP wrote a

letter to RCT requesting final design approval for an interlocking tower to

control the crossing of the SA&AP and the GH&SA at "Blodgett" (henceforth, RCT

always identified the tower's location as "Blodgett".) RCT responded with written

approval three weeks later. The tower was built during the next three months,

and on July 4, 1903, RCT authorized the newly-designated Tower 12 to begin

operations. The Tower 12 interlocker was a minimal design, a 12-function

mechanical plant with twelve levers, its maximum capacity. The twelve functions

consisted of a home signal, a distant signal and a derail in each of the four

directions. RCT records state that the interlocker was installed by the GH&SA,

which undoubtedly also took responsibility for operations and maintenance

(O&M) of the tower, the interlocking plant and its associated track

signals. The simplicity of the interlocker's functionality resulted in the O&M

expenses being shared equally between the two railroads (they each used half of

the functions.) Because both lines existed prior to the 1901 state law granting

RCT authority over crossings of two or more railroads, the entire capital

outlay for the tower and associated equipment was split

equally. (The capital expense for a newer crossing would be borne by the railroad that created it, typically

the second railroad to arrive.) By June, 1906, Tower 12 was seeing an average of

24 movements per day.

The assumption is that Tower 12 was a two-story manned

structure of SP design, probably identical, or nearly so, to Towers

13, 14, 15,

16 and 17, all of

which were SP towers that commenced operation in the same month as

Tower 12. The tower's limited lifespan (about a dozen years) helps explain why no

photograph of it has been found. Documentation from the RCT interlocker archives maintained at DeGolyer

Library, Southern Methodist University shows a connecting track in the southeast

quadrant of the crossing on a map dated April 9, 1903. A map dated April 8, 1907

shows a connecting track added in the northwest quadrant, and also depicts the

"Houston Electric Railway" passing near the tower.

|

By 1910, Houston had become a severe bottleneck for SP.

The GH&SA line through Montrose was SP's primary line

between the Sunset Route in south Houston and its north side

railroads. SP's other option was the Galveston, Houston &

Northern (GH&N, acquired in 1905) which operated in east Houston on both

sides of Buffalo Bayou. It had tracks south to Harrisburg where it

connected to the GH&SA, but it was less convenient for Sunset Route traffic.

The flat terrain around Houston had motivated the GH&SA to build the line

through Montrose on an embankment, causing serious drainage issues

in the neighborhood. Eleven street grade crossings had been added due to

residential population growth, so the city

had set a train speed limit of six miles per hour. Another thirteen streets were simply blocked by the embankment. Everyone wanted

it gone.

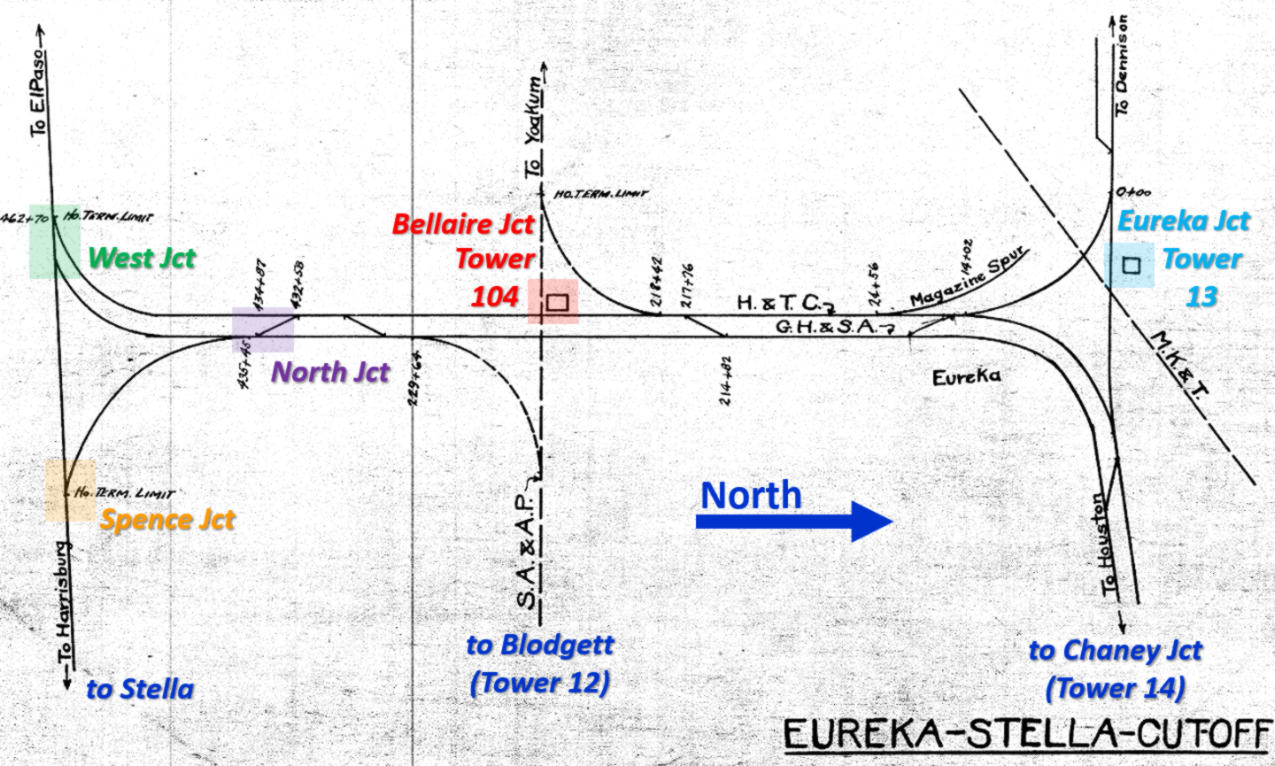

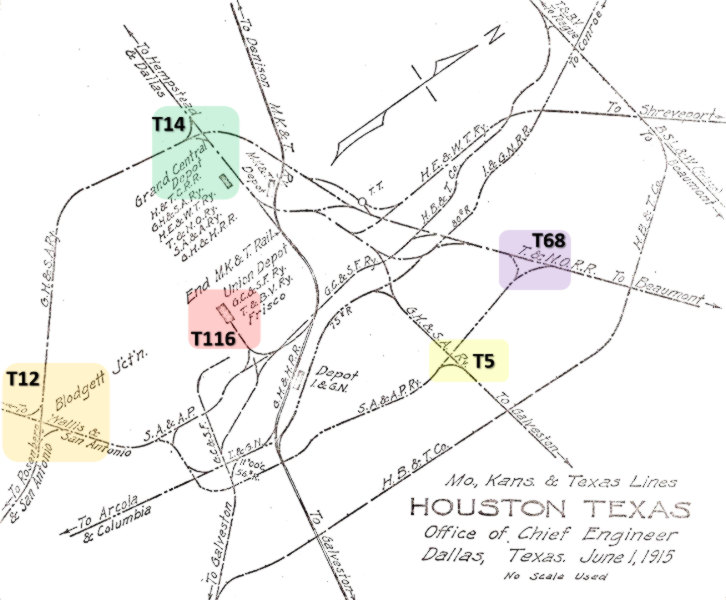

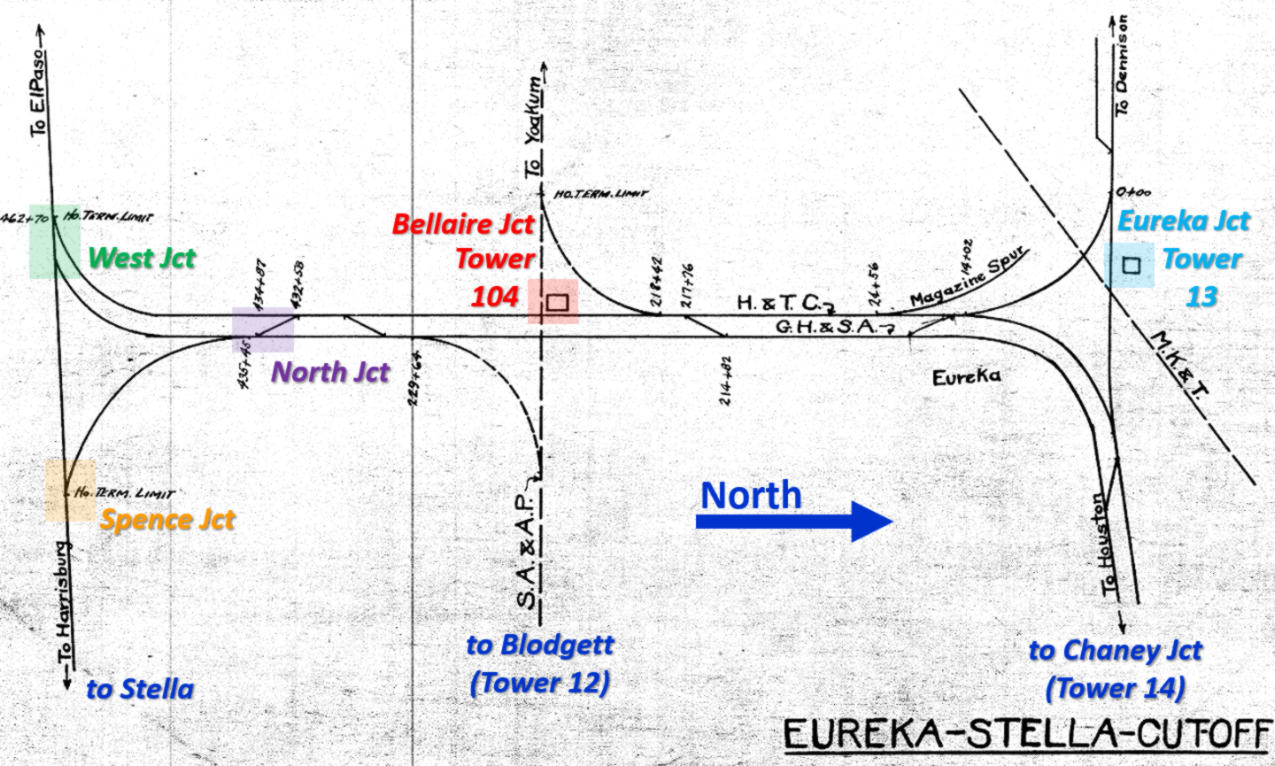

Left: This 1915

track chart (courtesy Ed Chambers) from the Chief Engineer of the

Missouri, Kansas & Texas (MK&T) Railroad (drawn with a 45 degree east

rotation) shows that Tower 12 had connecting tracks in two

quadrants. The northwest track was installed c.1907. SA&AP passenger

trains might have used it to reach SP's station, although a 1908

timetable shows them operating out of Union Depot (they resumed using

SP's station by 1915.) The southeast quadrant track (date unknown) was

likely added by SP after it acquired the SA&AP in 1892. RCT's function count for

the Tower 12 interlocker never changed

during its existence, suggesting that the connecting tracks were not signaled

or switched through

the interlocker. Englewood Yard (Tower

68) opened in 1895, and the SA&AP reached it over a line they built

at that time. Tower 5 was commissioned where the SA&AP crossed SP's line that ran east from downtown.

Note that in addition to SP's "Grand Central Depot", three other passenger

depots are shown on the track chart: the downtown "Union Depot" (red highlight) known

officially as Union Station (Tower 116),

plus separate depots for both the I&GN and

MK&T. Ultimately, Union Station and SP's Grand Central Station would handle

all passenger traffic in Houston. [not all interlocking towers and

railroads are shown] |

SP was willing to abandon the Stella - Chaney Junction

line; it would never be able to support the double track between north and south Houston

they needed. SP's plan was to have the H&TC lay a nine mile cutoff from Eureka Junction

in northwest Houston south to the GH&SA main line at Stella. This "Eureka - Stella Cutoff"

coupled with the

H&TC tracks between Eureka and Chaney junctions would replace the GH&SA line

through Montrose. SP also

planned to construct a second line from Stella to Eureka Junction that would

continue east to Chaney Junction, paralleling the

H&TC and connecting into the GH&SA tracks on the north side of Chaney Junction.

Those tracks led farther east to the T&NO at Tower 26.

SP was willing to abandon the Stella - Chaney Junction

line; it would never be able to support the double track between north and south Houston

they needed. SP's plan was to have the H&TC lay a nine mile cutoff from Eureka Junction

in northwest Houston south to the GH&SA main line at Stella. This "Eureka - Stella Cutoff"

coupled with the

H&TC tracks between Eureka and Chaney junctions would replace the GH&SA line

through Montrose. SP also

planned to construct a second line from Stella to Eureka Junction that would

continue east to Chaney Junction, paralleling the

H&TC and connecting into the GH&SA tracks on the north side of Chaney Junction.

Those tracks led farther east to the T&NO at Tower 26.

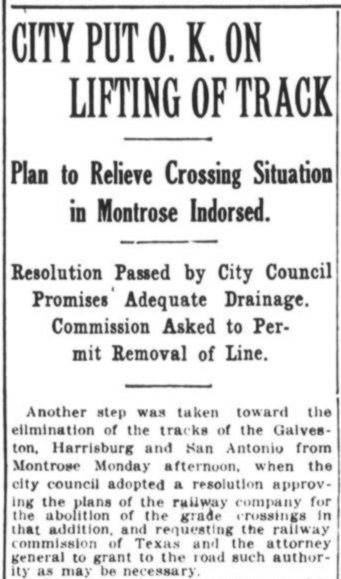

Left: The City of

Houston supported SP's plan to remove the tracks through Montrose. Their City Council resolution was forwarded to RCT to request

approval of SP's plan. (Houston Post,

June 22, 1915)

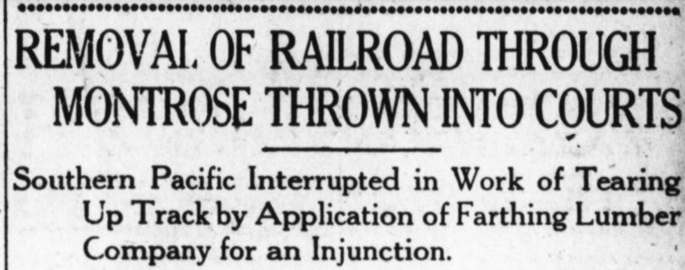

Below:

The Houston Post

of Saturday, July 17, 1915, reported that not everyone was on board with

removing the tracks through Montrose. A lumber company near Blodgett on the

GH&SA line filed a lawsuit to prevent impending loss of service, and requested a

preliminary injunction (i.e. before trial) against the GH&SA's salvage

activities. The story mentions that the final train to use the tracks had passed

through Montrose on Thursday night, two days earlier. The Eureka - Stella Cutoff

was deemed fully operational, so abandonment of the tracks north from Blodgett

through Montrose had begun immediately. Complicating matters, in January, SP had

sold two miles of right-of-way through Montrose to the Houston Land Corp, which

had a vested interest in seeing the rails and ties removed as quickly as

possible. They would then deconstruct the embankment so

they could sell residential lots on the former right-of-way.

|

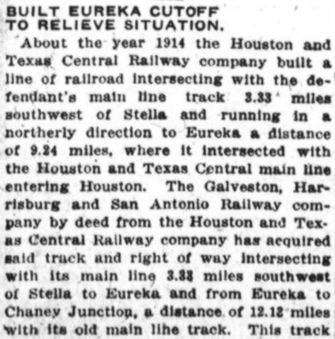

As noted in the Houston Post story

above, track removal began in the Montrose area after the last train

passed on July 15, 1915. It was undoubtedly a passenger train because

GH&SA freight trains had been using the Eureka - Stella Cutoff since

November 16, 1914. At least by January, 1915 if not earlier, SA&AP passenger trains

had resumed using SP's station and may have been routing there via

Chaney Junction and the northwest quadrant connector at Tower 12. If so,

closing the line through Montrose forced them to return to their own

tracks to cross Buffalo Bayou and reach the SP station (from the opposite direction.) On August 14, 1915, the judge

denied the

lumber company's request for a preliminary injunction.

News of the judge's ruling appeared in the

Houston Post

the next day, Sunday, August 15th. The entire ruling was reprinted, providing details (left)

about the history of these rail lines. In particular, the ruling

states that the newly constructed line and

the existing track between Eureka and Chaney junctions had been deeded

by the H&TC to the GH&SA. Also, the

connection to the GH&SA main line was not at Stella; it was

3.33 miles

southwest of there, a location that would become known as West Junction.

As the track approached West Junction from the north, it curved west to

connect into the GH&SA Sunset Route. There

appears to have been

a connecting track back to the east to support Eureka - Harrisburg

movements. This connection was identified in a 1916 court document as "East H&TC

Junction", presumably not

the Spence Cutoff that exists today.

The removal of tracks through Montrose did not

resume immediately

because the denial of the preliminary injunction was appealed. The

appeal was soon rejected by the appellate court, so track removal

through Montrose was restarted and was probably complete by the fall of

1915. The legal case was not over; the preliminary injunction had

been denied but the lawsuit still had to go to trial. |

RCT construction records list a 9.53-mile track segment

completed in 1915 by the H&TC from Eureka to "Stella", notwithstanding the

3.33-mile discrepancy between Stella and West Junction noted above. Stella was

not otherwise significant, and the source of the name is undetermined. If it was

a community, there should have been an occasional mention of it in the

Houston Post, but no such references are found. While the origin of the name is unknown, the location of

its switch to

Chaney Junction is well known, stated in timetables as 0.2 miles west of Pierce Junction. East of Stella

and Pierce Junction, the GH&SA tracks to Harrisburg had not been part of the Sunset Route,

yet Harrisburg had been a significant crossroads for SP due to its connection to

the Port of Galveston via the Galveston, Houston & Henderson (GH&H) Railroad.

It

remained important because of SP's 1905 acquisition of the GH&N. The GH&N served

the north and south banks of the Houston Ship Channel, which had formally opened

September 7, 1914. The GH&N also had a bridge over

Buffalo Bayou adjacent to

the upper end of the Ship Channel. South of the bridge, the tracks went through

Magnolia Park to Harrisburg, La Porte and

Galveston.

Abandoning the tracks through

Montrose also eliminated the need for the interlocker at Chaney Junction; there

was no longer a crossing. The H&TC track from Eureka (now reportedly owned

by the GH&SA) passed

through Chaney Junction, continued southeast to the SP passenger

station, and then curved back to the northeast to connect with the T&NO near

Tower 26. When the T&NO leased (1927) and then merged (1934) most of SP's Texas

railroads, this became known as T&NO's Passenger Line. GH&SA tracks

still existed on the north side of the junction where a switch connected them

westbound to Eureka and eastbound to the

T&NO near Tower 26; this became known as T&NO's Freight Line.

With the crossing gone, SP wrote a short

note to RCT dated November 17, 1915 stating "FYI, we have removed crossing of the GH&SA Railway Co.

and the H&TC Railroad Co. main line at Chaney Junction and have discontinued

operation of Interlocking Plant #14." SP did not, however, completely

remove the tracks south of Chaney Junction. They retained one mile as

an industrial spur, which survived into the 1990s.

|

About four miles south of Eureka Junction, the Eureka -

Stella Cutoff crossed the SA&AP main line into Houston. The crossing was

at grade, so an interlocking tower was planned and built by SP. RCT

records identify it as Tower 104, commissioned for operation on

February 11, 1916 with a 17-function mechanical plant. RCT officially reported

its location as Bellaire, a

community founded in western Harris County c.1911. RCT listed the GH&SA,

the H&TC, and the SA&AP as the three participants at Tower 104, with O&M

responsibility assigned to the GH&SA.

Left:

After briefly mentioning a new GH&SA tower at San Antonio (Tower

105), this news item from the November, 1915 issue of

The Signal Engineer asserts that

the new Bellaire tower would be using the old interlocking plant from

Blodgett. Tower 12 served no purpose after the tracks to Chaney Junction

were closed, but details of its removal have not been found. Consistent

with the story at left, it was likely dismantled in the fall of 1915 as

Tower 104 was being constructed. RCT's annual interlocker list dated

October 31, 1915 showed Tower 12 as retired. |

|

Left: (Houston Post,

June 13, 1916) While waiting for the trial date to be set for the

lumber company's lawsuit, the GH&SA had sought an order from RCT

specifically authorizing abandonment of the tracks from Stella to Chaney

Junction. They believed they already had such authority, but a

contemporary confirmation from RCT would be valuable evidence at trial.

The lumber company testified in opposition to the GH&SA petition at a

hearing held by RCT in June, 1916.

The tracks south of Blodgett had

remained intact, apparently as a temporary compromise for the infrequent

delivery of a carload of lumber while the legal proceedings played out.

The dismantling of the tracks north of Blodgett had resumed in

August, 1915 when the injunction was denied, and the work was likely completed

soon thereafter. By June, 1916, the tracks through Montrose had been

gone for many months, the Eureka - Stella Cutoff had been operational

for a year and a half, and RCT had already commissioned Tower 104. Thus,

despite legal rhetoric about "changing" the Stella - Chaney Junction

line, RCT's only real decision was whether to confirm authorization to abandon

the line and the

station at Blodgett.

Right:

The Houston Post of October 1,

1916 reported that grading was in progress on the second track for the

"Stella - Eureka" Cutoff. |

|

Not satisfied with the success of finally removing the

GH&SA grade through

Montrose, the City of Houston demanded that the SA&AP remove its grade crossings

at Montrose Blvd. and Main St. which had

become major thoroughfares. Making the crossings grade-separated was too expensive, so rather than fight the City, the SA&AP

petitioned RCT on August 26, 1916 for permission to abandon their tracks between

Bellaire Junction and Blodgett. The SA&AP asked RCT to grant permission to

reroute its trains between Bellaire Junction and Blodgett via the

"East H&TC Junction" (presumed to be in the immediate vicinity of West Junction) and then north at Stella using the

GH&SA track that remained intact to Blodgett. (So ... the GH&SA was

seeking authority to

abandon the tracks from Stella to Blodgett while the SA&AP was seeking

authority to start using them!)

As an alternative, the SA&AP proposed

building a new line east from Bellaire Junction on a different right-of-way,

bypassing Blodgett and incorporating the required grade separations. Blodgett

was simply too close to Main St. to be retained; having a station there would

force the tracks to cross Main St. at grade. RCT held a hearing on the matter on

October 24, 1916. Ironically, although the City of Houston had proposed grade

separation as a possible solution, its mayor opposed the idea in his testimony,

stating that the long approaches needed for grade separation would create new

drainage problems! The SA&AP petition was opposed by the same lumber company

that was fighting the GH&SA. Their uncompromising position was that the station

and public tracks at Blodgett had been illegally removed, hence they needed to

be fully restored to operation. Yet, in

court proceedings against the GH&SA, the lumber company had claimed the SA&AP

was not a viable option for lumber deliveries, the excuse being that the SA&AP

did not serve east Texas lumber mills. The SA&AP had filed a separate petition

to abandon the station at Blodgett, but they asked to dismiss it on the grounds that it merely duplicated part of the GH&SA petition that

was already being considered. RCT granted the dismissal on July 13, 1916.

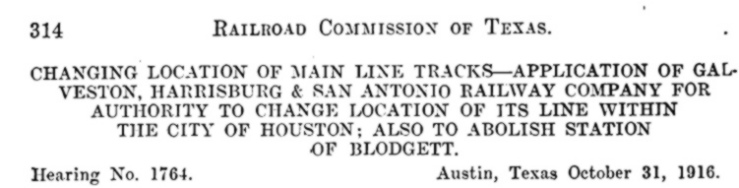

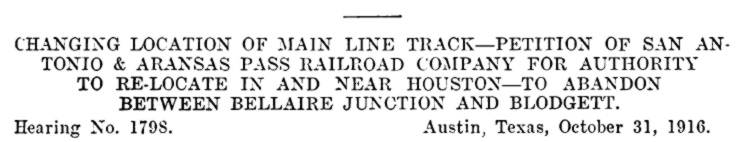

Above: On October 31, 1916,

RCT issued decisions simultaneously on the two petitions pertaining to the

tracks at Blodgett. The GH&SA's petition (left)

was granted in full, finding that permanent abandonment of the Blodgett station

and the GH&SA tracks that served it was in the public interest. RCT also found that the GH&SA

had acted

in good faith based on previous RCT rulings, and they specifically ratified the

GH&SA's "...prior acts in the abandonment of said stations and relocation of

said tracks..." Again, the references to "Change Location" were irrelevant; the

Eureka - Stella Cutoff had been open for nearly two years, so abandonment was

the only issue.

In the second case (right),

RCT granted the SA&AP's petition to abandon the Bellaire Junction - Blodgett tracks and begin operating

to Blodgett via West Junction and Stella. Significantly, RCT did not

order the SA&AP to begin this reroute and it did not order them to abandon the

Bellaire - Blodgett tracks. It simply authorized them to do so, and to negotiate

trackage rights with the H&TC and GH&SA as necessary.

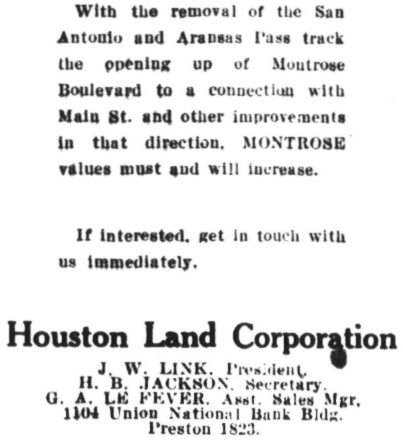

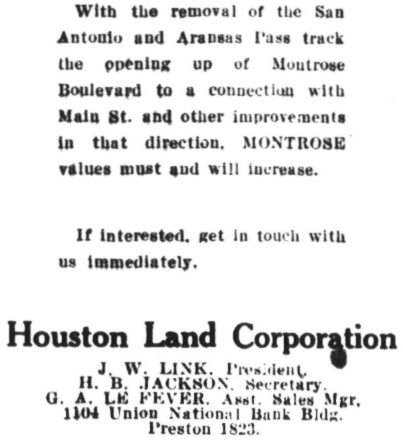

Left:

It was the Houston Land Corporation to which SP had sold two miles of

right-of-way in Montrose prior to the physical removal of the Stella - Chaney

Junction tracks. And with the news (from only three days earlier) that RCT had

approved removing the SA&AP tracks between Bellaire Junction and Blodgett including the grade crossings

at Main St. and Montrose Blvd., the land company

wasted no time in promoting the news as another reason to invest in Montrose

residential property. (Houston Post,

November 3, 1916)

Left:

It was the Houston Land Corporation to which SP had sold two miles of

right-of-way in Montrose prior to the physical removal of the Stella - Chaney

Junction tracks. And with the news (from only three days earlier) that RCT had

approved removing the SA&AP tracks between Bellaire Junction and Blodgett including the grade crossings

at Main St. and Montrose Blvd., the land company

wasted no time in promoting the news as another reason to invest in Montrose

residential property. (Houston Post,

November 3, 1916)

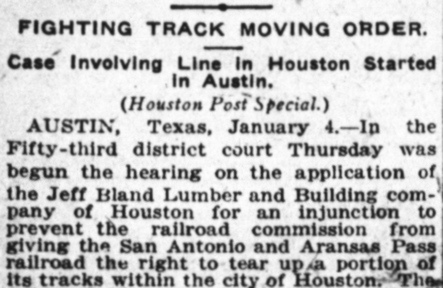

Below:

The reality was, it would take time (more than anyone imagined!) to abandon the

tracks at Montrose

Blvd. and Main St. And of course, the lumber company sued RCT in district court to have the

ruling set aside. (Houston Post,

January 5, 1917)

There's no indication that the SA&AP initiated negotiations with SP for

the trackage rights needed for the reroute plan. Perhaps they were having second

thoughts; was there another solution to address the grade crossings at Main St. and Montrose Blvd.? There

was still the possibility of buying the Stella - Blodgett tracks that the

GH&SA was trying to abandon,

yet the entire reroute idea seemed like a poor solution. The lumber company's

lawsuit to set aside RCT's ruling for the SA&AP was dismissed by the district judge on

February 16, 1917, and its lawsuit against the GH&SA to reinstate

the line through Montrose still had

no trial date. If the lumber company won at trial, the GH&SA grade crossing on

Main St. would be put back in place, and the SA&AP could resume serving Blodgett,

but only

if its tracks were still intact. Thus, SA&AP's strategy for 1917 appears to have

been simply to wait for further legal developments.

Below: This c.1920s T&NO track chart (courtesy

T&NO Archives) of the Eureka -

Stella Cutoff illustrates the completed double track. Per the

Houston Post report, grading on the second

track was underway by October, 1916, so it was most likely operational in 1917.

RCT records show it as GH&SA construction from Chaney Junction to West Junction,

a distance of 12.18 miles, completed in 1918. Both tracks merged directly into

the Sunset Route at West Junction; today, this is double

track from there all the way to

Sugar

Land. At some point, perhaps during construction of the second line, a new connecting

track for eastward movements was added that merged into the GH&SA main line at a

location now known as Spence Junction. A 1920 SP timetable calls it "East

Junction", and identifies the

opposite end of the connector as "North Junction." Although the construction

date of the "Spence Cutoff" remains undetermined, it was clearly built

to increase the track radius of the

curve required to navigate the acute 66-degree angle for movements between Eureka

Junction and Harrisburg. This presumes that "East H&TC Junction",

a name thus far found only in court documents, is neither

"East Junction" nor "North Junction", and was removed when

the Spence Cutoff was built. The diagram also shows Tower 104 located in the

northwest quadrant of the crossing. As no photos of the tower have surfaced,

this is the only evidence of its location with respect to the diamonds.

Note that the GH&SA and H&TC are identified as the owners of the east and

west tracks, respectively, between West Junction and Eureka. Functionally, it

didn't matter; they were both SP properties. RCT records list abandonment of

10.54 miles of track by the T&NO in 1934 from Chaney Junction to Eureka

Junction. The distance between Chaney and Eureka is only three miles, and the

double track remains intact, so this may have been removal of spur and siding

tracks. It's also possible this was some sort of an accounting

adjustment

by T&NO since 1934 was the year it formally merged the H&TC and the GH&SA.

The

lumber company took no further action to press their lawsuit in court until July 12, 1917 when it filed

a second amended complaint. The District Court responded by setting a trial date for

March 5, 1918. The trial was conducted, and shortly thereafter, Judge Ashe ruled against the lumber

company, which appealed the ruling. The appeal went to the Court of Civil Appeals in

Beaumont,

which held

a hearing a year later on April 28, 1919. Judge Ashe's ruling against the lumber company was

affirmed by the Appeals Court on May 7, 1919. In a key passage of its ruling,

the Appeals Court noted that after the track removal had been completed through Montrose

(probably by October, 1915), the Houston

Land Corporation had removed the embankment, and the City had reconnected

streets across the right-of-way, closing some and opening new ones. The Court

explained that "...the Houston Land Corporation sold to various and sundry

parties -- some 12 or 15 or more, in number -- portions of said right of way and

roadbed, and some 12 or more citizens have constructed beautiful and costly

houses upon said right of way and roadbed, and same are now being occupied as

residences." Translation... "Rich people have built big homes on the

right-of-way. You lose."

The Court's legal rationale for ruling

against the lumber company was based on two arguments. First, the lumber

company's second amended complaint had failed to include as defendants the City

of Houston, the Houston Land Corp., and the homeowners who had acquired land on

the right-of-way. Even if the GH&SA's abandonment and track removal was illegal

at the time it was undertaken (and the court agreed with the lumber company that

it was), the Court could not order the requested remedy of rebuilding the line

because those landowners had not been summoned to court to defend their property

interests. The lumber company did not contend that the landowners had notice of

the pending lawsuit when they acquired their parcels, which might have made a

difference. But...the lumber company would have lost anyway. Even if the GH&SA's

actions were illegal when undertaken, the Legislature had passed a

law in 1917 validating all "...changes, relocations and abandonments of

parts of their lines by railroad corporations or receivers of any railroad in or

adjacent to any city having a population ... of 50,000 inhabitants or over,

heretofore made with the permission of the Railroad Commission of Texas..."

In other words, track changes like this one in large, populated areas were now

automatically assumed under state law to be valid so long as RCT had granted

permission for the change. Furthermore, such changes no longer required a railroad's charter to be revised by the Legislature. RCT's ruling

in October, 1916 in favor of the GH&SA had granted that they acted in good faith

based on prior RCT rulings, so the GH&SA had effectively complied with the law's

provision to obtain prior RCT approval. The Court also noted that the

Legislature had the right to retroactively amend state law to validate these

types of actions, hence they had become legal, even if they weren't at the time.

And with that ruling, the

legal case pertaining to the abandonment of the Stella - Chaney Junction line

had finally ended...

...or maybe not!

Right:

Houston Post, April 23, 1919

Since the

GH&SA had RCT permission, and since there was no court injunction against

them, they had decided to begin abandoning the remainder of the line

between Stella and Blodgett in April, 1919. Why they chose to do this a

week prior to the appellate hearing is unknown; perhaps there was a

legal angle involved. The Texas Attorney General did not take it well,

asking the district court not only to stop the work with an injunction, but

also requesting a mandamus order for the GH&SA to put the tracks back in place and pay a $5,000

fine! In the appellate

hearing scheduled at Beaumont the following week, the State of Texas was

not a party, but RCT had

third-party interests (having approved the GH&SA's actions) which the Attorney General might have been

protecting in some way.

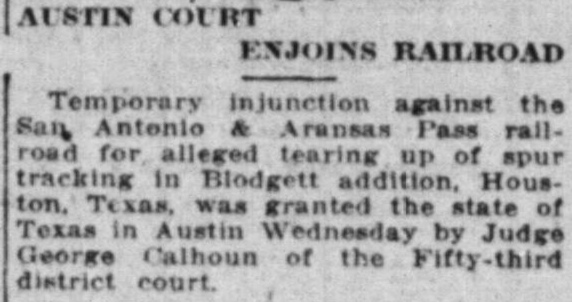

Below: To add to the confusion, on April 30, 1919, the judge

also entered a temporary injunction against the SA&AP for the same

reason. (Austin

American, May 1, 1919)

Legal

terms: Legal

terms:

injunction = "stop doing the bad things you're doing"

mandamus = "take this action to remedy the bad things you've already done"

No other newspaper references to these temporary injunctions have

been found. It seems likely that once the appellate

ruling was issued on May 7 granting the GH&SA a complete victory in its

attempt to abandon the Stella - Chaney Junction line and the

station at Blodgett, the temporary injunctions were either dismissed

outright or allowed to expire on their own terms.

|

|

|

|

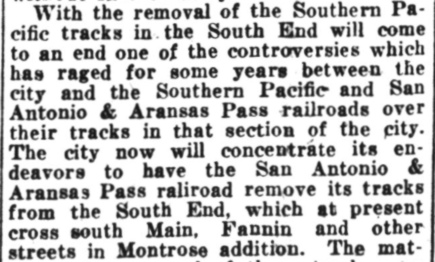

Left:

(Houston Post, November 17,

1920) RCT had approved abandonment of the SA&AP's tracks between Bellaire and

Blodgett on October 31, 1916, but the order did not require it. It was up to the SA&AP to

negotiate with the City of Houston on a plan moving forward, which might

or might not involve abandonment. Whether any

progress was made during 1917 is unknown, but by the end of that year,

it didn't matter. The railroads were nationalized under the U. S.

Railroad Administration (USRA) on December 28, 1917 to optimize their use in

support of World War I. Facilitating a reroute

simply for the convenience of removing two grade crossings was not

the kind of expenditure of time, money and manpower that USRA would view

favorably while trying to manage the nation's railroad network for wartime

production. The issue of the Main and Montrose grade crossings went

dormant.

The Transportation Act of 1920 returned the railroads to

private ownership, but it also granted substantial control over

them to the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC). Trying to force

the SA&AP to remove the grade crossings and reroute trains would

encounter significant administrative delays through the ICC, and there was a good

chance the City would lose anyway. Thus, the City was willing to accept

a solution that involved significant improvements to the grade crossings

to render them less objectionable. |

The SA&AP's tentative agreement with the City regarding the grade

crossings at Montrose Blvd. and Main St. would eliminate the need to

abandon the Bellaire - Blodgett tracks. This meant that Tower 104 would retain its

purpose. It would not have been needed if the SA&AP tracks merely merged into

the GH&SA or H&TC tracks at Bellaire rather than crossing them. Yet,

during USRA control, that is effectively what happened. An SA&AP employee

timetable issued by USRA on October 12, 1919 specifically states "All trains

use H&TC tracks between Bellaire Jct. and Englewood..." Although

passenger trains went to Grand Central Station and freight trains went to

Englewood, the route from Bellaire was the same, via Eureka and Chaney junctions. Significantly, this arrangement

continued for SA&AP passenger trains after USRA control was dissolved on March

1, 1920. The grade crossings near Blodgett had seen no trains during more than

two years of USRA control, but only the SA&AP freight trains were returning. The

reduced train count may have motivated both parties to seek a more realistic solution for the grade crossings at Main and

Montrose. Whether the November, 1920 agreement to lower the tracks was actually implemented has not

been determined.

Houston Post, November 9, 1921 |

Left: There's no evidence that the appellate ruling in May, 1919 was appealed to the Texas Supreme Court.

Nothing prevented

removal of the GH&SA tracks between Stella and

Blodgett, yet USRA control undoubtedly delayed the effort. On November

7, 1921, Mayor Holcombe of Houston received

a letter from "President W. R. Scott of the Southern Pacific lines in

Texas" stating "We have received authority

to abandon the tracks...", but it does not say by whom such authority was

granted (possibly higher level SP corporate management.) The letter promised

that SP would proceed "...without further delay." The City

then planned to "concentrate its endeavors" for the same result with

the SA&AP.

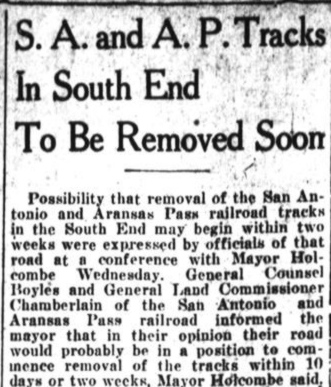

Right:

(Houston Post, December 1,

1921) The City and the SA&AP agreed to negotiate removing the tracks at Main St. and other nearby

streets. A March, 1922 Houston Post

story discussed the negotiations; the SA&AP wanted to trade the removal

for a new right-of-way on Hutchins St. near the SA&AP freight yard.

It appears that nothing came of the discussions because a

November, 1924 SA&AP timetable shows freight trains operating from

"Houston (Frt. Yard)" to Bellaire Junction, with no indication

of routing via Eureka

Junction (movements on non-SA&AP tracks would have been noted by declaring

the proper timetable rules to follow.) |

|

The Transportation Act of 1920 directed the ICC to

promote and plan for the consolidation of U.S. railroads into a limited number

of "systems". The ICC responded by hiring economist William Z. Ripley to develop

a plan. The so-called "Ripley Plan" proposed that SP head one of these systems,

with the SA&AP becoming part of it. On December 6, 1924, SP filed an application

with the ICC for authorization to obtain control of the SA&AP. The State of

Texas opposed the move, but was overruled by the ICC, which granted SP's

application. In March, 1925, the SA&AP was re-acquired by SP and leased to the

GH&SA. This put all three railroads at Tower 104 under SP control, so SP began planning to suspend Tower 104 operations and

redesign the junction. SP documentation shows Tower 104 being taken out of

service on July 7, 1925. SA&AP passenger trains were already operating between

Bellaire Junction and SP's Grand Central Station via Eureka Junction. With the

tower closed, SA&AP freight trains began using Eureka Junction to reach

Englewood Yard. In

1926, the two diamonds at Tower 104 were removed and presumably, the tower

structure was razed or relocated; its disposition has not been determined. RCT

listed Tower 104

as retired in its table of interlockers dated December 31, 1926. To the extent

necessary to transition its operations, SA&AP freight trains north of Buffalo

Bayou could still reach SA&AP customers and the freight yard near downtown using

the SA&AP bridge over Buffalo Bayou via Tower 5.

Satellite imagery shows this bridge (a successor to the 1890s original?) surviving into the late 1990s, but it was

gone by 2002.

The tracks east from Bellaire Junction were cut back by SP,

eventually terminating near Shepherd Drive. Whenever this occurred (date

undetermined), the controversial grade crossings at Montrose Blvd and Main St.,

both farther east, were finally abandoned.

Over many decades, the line east of Bellaire Junction was simply a lengthy spur.

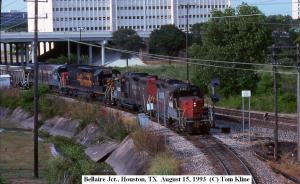

Tom Kline elaborates...

The last remaining business on

this line was Stahlmanís Lumber on the corner of Shepherd Drive and the US 59

access road. I believe there was a short siding/spur there for them. I never saw

the line this far east in operation but I remember the rails and a low level

switch stand stood near the lumberyard at the Shepherd Drive crossing for years

afterwards in the mud and weeds. ... SP had a Public Freight Track access area

for shippers which I believe was on the corner of Westpark Drive and Wakeforest. This

was an area of team tracks where local shippers could load/unload their

shipments and sometimes a localís power would be spotted there. ... After the

line was abandoned from T-104 west to Wallis, the eastern portion to Kirby Drive

was in service for several years afterwards. The circus would use it annually

when they performed at The Summit arena, spotting the animal cars there and

parading the elephants and equipment onto the Edloe Street bridge to cross over

US Hwy 59 to the performance venue across the freeway. In the interim, as

aggregate business was booming, SP would spot many rock trains on this track for

unloading. Most of these consists were unit trains of gondolas unloaded by

excavators on crawlers.

Ciff Tyllick provides these comments about the tracks

east of Bellaire Junction (thanks, Cliff!)...

In 1963, my family moved to a

house near Rice University. ... I rode my bike or took a bus across those

tracks every school day for about 12 years. About 1970, the rails were taken up

from just east of Shepherd towards Montrose. I donít recall how far towards

Montrose they extended, but I think itís safe to say that they had not been

maintained east of Hazard for decades. ... Trains continued to serve Stahlman

Lumber into the 70s. Iím not sure when that service ended. They did have a spur

that entered the lumberyard. I remember waiting on my bike, in a car, or on a

bus at Shepherd as well as Greenbriar many times for the train to finish

switching out cars. The other customer of the railroad was a concrete batch

plant just across the tracks, between Greenbriar and the back of the fire

station on South Shepherd, which is now the Sherwin Williams paint store. Except

for the fire station and perhaps one other building on South Shepherd, the batch

plant occupied the entire block between the railroad, Greenbriar, Milford and

South Shepherd. The railroad supplied it with sand, aggregate, and cement, and

the batch plant had its own spurs that remained in the weeds for years after it

shut down. The batch plant remained in operation until some time after 1970 and

perhaps as late as 1975. I think it sat idle for a few years and was dismantled

about the same time the apartments were built at 4100 Greenbriar, which would

have been right about 1975. So it wasnít just the lumberyard that was keeping

the rail line in service. Of course details recorded in history could be

different from the way I so clearly recall them, but I hope this gives you a

better reference point for when Southern Pacific shut down this old San Antonio

and Aransas Pass line.

click image to enlarge |

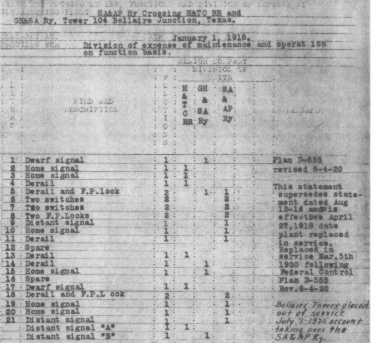

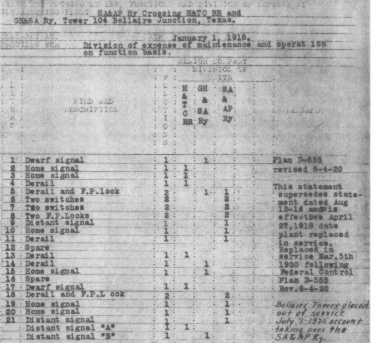

Left:

SP used an internal form to document its agreements with other

railroads pertaining to management of interlocking towers. This one for Tower

104 (from the

Carl Codney Collection) is dated January 1, 1918, superseding the original

form dated April 7, 1916. The lower portion of the form has been

omitted; it only showed the O&M expense shares, which were H&TC, 23.08%;

GH&SA, 19.23%; SA&AP, 57.69%. Typed notes on the form reveal it

"...is effective April 27, 1918 date plant placed in service." Since

Tower 104 had been commissioned on February 11, 1916, why was the plant

"placed in service" two years later? Simple speculation is that instead

of attempting to further expand the capacity of the original plant from

Tower 12, a larger interlocker had been ordered to facilitate adding

controls for the second main line between

Eureka Junction and West Junction. Under this theory, a new function and

lever assignment plan could be generated, presumably on January 1, 1918,

based on the particulars of the new plant. When it arrived, it

was installed and the connections were made to implement the new plan

resulting in a service date of April 27, 1918.

Another typed note

on the form says "Replaced in service Mar. 5th 1920 following Federal

Control". USRA control of the railroads officially ended March 1, 1920,

so on March 5, the railroads returned Tower 104 to service. Thus, it was

"Replaced in service" because it had been out of service during USRA

control. During that period, all SA&AP trains routed via Eureka Junction;

SA&AP passenger trains continued to do so for the remainder of SA&AP's

existence.

The form includes a typed

note indicating unspecified revisions were made to the interlocker plan,

identified as D-555, on August 4, 1920. A final, handwritten note on the

form states "Bellaire Tower placed out of service July 7, 1925 account

taking over the SA&AP Ry." SP had acquired the SA&AP in March,

1925. |

|

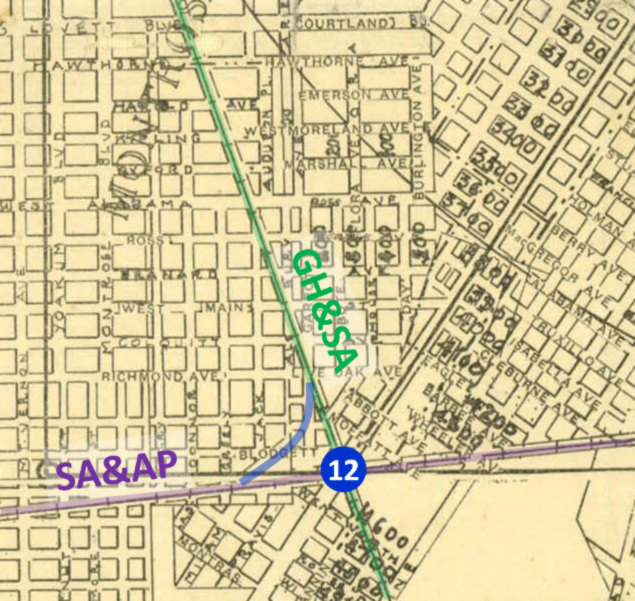

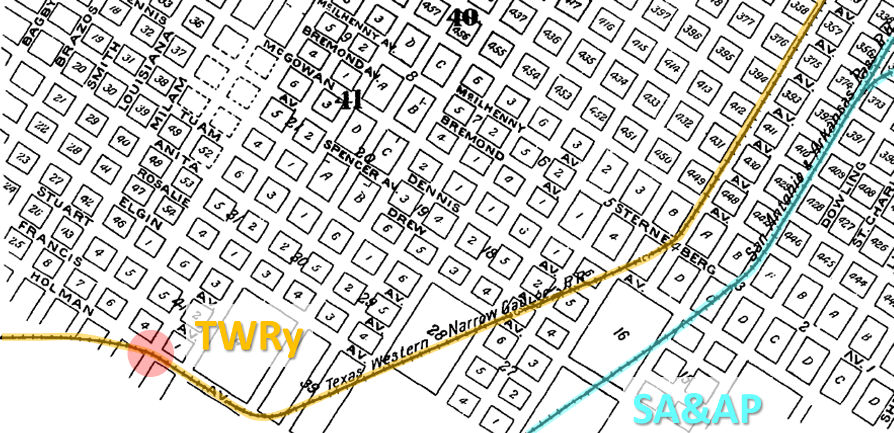

Left: This map of

Houston, reportedly from 1913, shows the GH&SA / SA&AP crossing served

by Tower 12, but it omits the northwest quadrant connector (blue line)

installed c.1907. The diagonal street at Tower 12 is South Main; the

diamond was probably a few yards east of Main. Blodgett St. is visible

near the crossing. It still exists, now mostly southeast of Main. The

precise location of Tower 12 is undetermined, perhaps in the vacant area

southeast of the diamond.

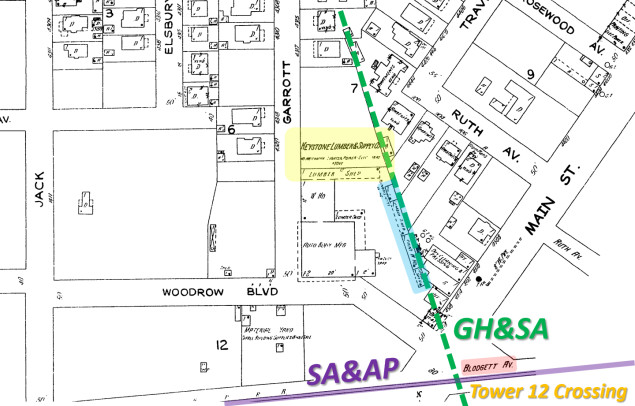

Below: On this 1924 Sanborn

Fire Insurance Co. map, the former GH&SA right-of-way is detectable from

the orientation of a lumber shed and paint warehouse (blue). Keystone

Lumber Supply (yellow) is probably not

the lumber company that filed the lawsuit because the court ruling

states that the SA&AP "...main line track also adjoins plaintiff's

property." Note that compared to the 1913 map, Blodgett Ave. (red) has

been renamed Woodrow Blvd west of Main St.

|

From Sanborn maps and other resources, the GH&SA

northwest of Tower 12 is known to have passed through the intersection of

Garrott St. and Richmond Ave., streets that no longer cross due to freeway construction. Farther

northwest, the tracks passed through the intersections of Jack St. with W. Alabama

St., and Sanford St. with Lovett Blvd. The slightly curved part of Grant

St., between Pacific St. and Jackson Blvd., is built on the GH&SA right-of-way.

At least in the early 1950s, the spur that ran south from Chaney Jct. ended at

W. Dallas St. at its intersection with Columbus St. Farther north, Memorial

Heights Dr. occupies the right-of-way. In the other direction, southeast of

Tower 12, the GH&SA tracks crossed Caroline St. about a hundred feet northeast

of Rosedale, and continued southeast through the intersections of Wichita at La

Branch, and Crawford at

Palm. Farther southeast at Calumet, the tracks curved south and continued on a straight

line toward Pierce Junction; the right-of-way is now occupied by Almeda Rd.

The tracks curved west nearing Pierce Junction and connected to the Sunset

Route, about where the tracks now cross Knight Rd.

Above Left: This 1957 image ((c)historicaerials.com)

shows the tracks at Bellaire Jct. The red arrow is Westpark Dr. The

yellow arrow is the SA&AP track from the west which curves north onto the SP

double track (pink arrows.) The SA&AP formerly continued across the double track (yellow dashes) when Tower 104 was operational.

Southeast and northeast quadrant tracks (green and blue arrows,

respectively) are

visible connecting to the line eastward (orange arrow) toward downtown. The purple arrows

are industrial spurs. Above Right:

Bellaire Junction looks much different today. The double track is still intact,

now operated by SP successor Union Pacific (UP), and the electric power

substation at lower left is served by a spur off the west track. The former

SA&AP tracks have been removed in both directions; they

were officially, but not actually, abandoned in 1993. The abandonment

proceeding allowed the line to be conveyed by SP to an entity that was not a

common carrier, the Metropolitan Transit Authority of Harris County ("Metro"). SP retained an operating

easement on the line to continue to fulfill its common carrier obligations.

Acquiring SP in 1996, UP inherited this obligation and planned to continue

service until 2001. Meanwhile, a request to "railbank" the right-of-way was made

by Metro. The Surface Transportation Board granted a Certificate of Interim

Trail Use in November, 2000 covering the right-of-way from Milepost 3.48 near

Bellaire Junction to Milepost 52.9 located 8.3 miles east of

Eagle Lake. The tracks were removed and construction of the Westpark Tollway on

the SA&AP right-of-way began in 2001. It was completed in 2005, terminating

approximately twenty miles west of Bellaire Junction.

Below: This photo by Joe R.

Thompson (courtesy Railroad and Heritage Museum, Temple, Texas) was taken c.1950

looking north along SP's double track at Bellaire Junction. A standard automatic

interlocking cabinet is visible in the distance to the left of the tracks, just

beyond where the former SA&AP track from the west curves into the west

(left) track. The interlocking was added c.1945 for remote control (from Tower

13) of switches and an associated powered crossover. The precise control

arrangement is undetermined; remote controlled switches did not

usually require an interlocker, but this one apparently did. The semaphores visible at

left signalled trains on the ex-SA&AP line and have a "SA" placard,

indicating a semi-automatic signal. The block signal at right also has a "SA"

placard, and to its left, between the two tracks, a 2-light dwarf signal is

visible. To the right, the northeast quadrant connecting track comes in from the ex-SA&AP tracks east of

Bellaire Junction, with a sign (illegible) and a 2-light dwarf signal.

This track connects into the east (right) track near the interlocker cabin.

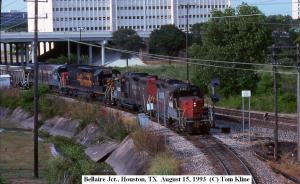

1993 Photos of Bellaire Jct. Operations,

courtesy of Tom Kline (click to enlarge)

East side of tracks, looking north |

West side of tracks, looking north |

West side of tracks, looking south |

|

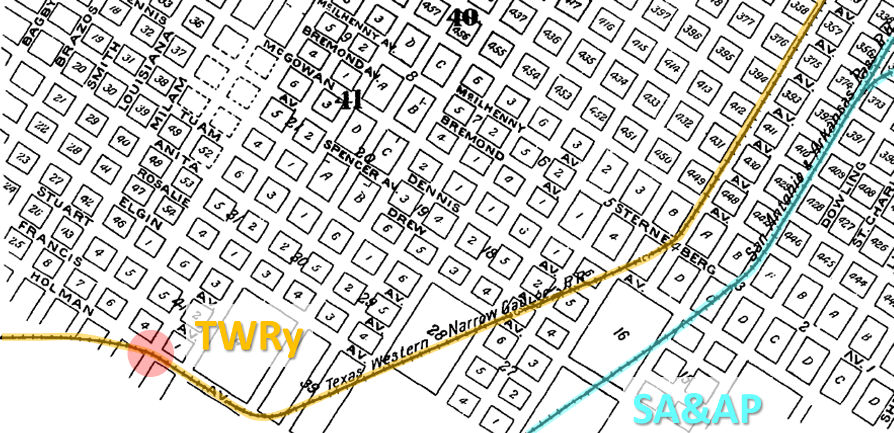

Left: There was

yet a third steam railroad with tracks through Montrose in the vicinity

of Blodgett. It was the Texas

Western Railway (TWRy), which this 1896 Sanborn Fire Insurance index map

identifies as the "Texas Western Narrow Gauge RR". South of downtown Houston,

its tracks were generally parallel to, and northwest

of, the SA&AP tracks. Unfortunately, the 1896 Sanborn map does not

extend farther west. Projecting the TWRy

route on a due west heading from the intersection of Holman and Fannin

(red circle) places it on what is now West Alabama, becoming Westheimer

Rd. farther west.

In 1877, the TWRy opened its line from Houston to

Pattison. After having its Brazos River bridge washed away three times

during construction, it finally reached Sealy

in 1882. In 1880-81, the GH&SA built across the TWRy near the intersection of Alabama and

Jack. The TWRy's narrow gauge prevented efficient freight exchanges

with other railroads, and it went into receivership in 1884. After a

decade in receivership, it was finally sold

in 1895. Operations stopped shortly thereafter and the rails were

removed in 1900. |

Julian Erceg found supporting information in research he conducted many years

ago...

...from

The Road to Piney Point

edited by Melissa M. Peterson, published by the Piney Point Village Historic

Committee in 1994: "In 1877, the Texas

Western Narrow Gauge was built from Houston to Pattison and San Felipe along the

route of present Westheimer Road, swinging northerly past Katy, TX. Piney Point

was a regular stop on this railroad although there is no evidence that any

station building ever existed. The TWNG owned 40 acres north of the line and to

the west of the Canfield homestead. A railroad bridge crossed the Piney Point

Gully to the west of Piney Point Road... A lady living on Piney Point Road

around 1950 retold this story about the Piney Point stop in the 1890's: As a

youngster she and her family, usually on a Saturday or a Sunday, caught the old

TWNG to Piney Point Station, walked down to Buffalo Bayou past the present site

of Vargo's restaurant to picnic areas and sandy beaches and cool clear water for

swimming. Late in the day they caught the train back to town. Apparently this

was a popular excursion for many Houstonians. The stopping place was near the

old Canfield House, but history does not record the role of its inhabitants in

this picnic site. This picnic area was either on Canfield property or on the

TWNG property to the west."

A History of the Texas Railroads

by S.G. Reed and Uriah Lott

by J. L. Allhands both use the same wording to suggest the route may have turned

west at Alabama. From Uriah Lott:

"...its freight and passenger stations

were located at the corner of St. Emanuel and Commerce Streets, and its tracks

ran out St. Emanuel to what is now known as East Alabama."

SP was willing to abandon the Stella - Chaney Junction

line; it would never be able to support the double track between north and south Houston

they needed. SP's plan was to have the H&TC lay a nine mile cutoff from Eureka Junction

in northwest Houston south to the GH&SA main line at Stella. This "Eureka - Stella Cutoff"

coupled with the

H&TC tracks between Eureka and Chaney junctions would replace the GH&SA line

through Montrose. SP also

planned to construct a second line from Stella to Eureka Junction that would

continue east to Chaney Junction, paralleling the

H&TC and connecting into the GH&SA tracks on the north side of Chaney Junction.

Those tracks led farther east to the T&NO at

SP was willing to abandon the Stella - Chaney Junction

line; it would never be able to support the double track between north and south Houston

they needed. SP's plan was to have the H&TC lay a nine mile cutoff from Eureka Junction

in northwest Houston south to the GH&SA main line at Stella. This "Eureka - Stella Cutoff"

coupled with the

H&TC tracks between Eureka and Chaney junctions would replace the GH&SA line

through Montrose. SP also

planned to construct a second line from Stella to Eureka Junction that would

continue east to Chaney Junction, paralleling the

H&TC and connecting into the GH&SA tracks on the north side of Chaney Junction.

Those tracks led farther east to the T&NO at

Legal

terms:

Legal

terms: