Texas Railroad History - Towers 102 and 208 - Houston (Magnolia Park)

Tower 102: Crossing of the Galveston, Harrisburg

& San Antonio Railway and

the International & Great Northern Railroad

Tower 208: Crossing of the Houston Belt & Terminal Railroad and the Port Terminal Railroad

Association (Public Belt Railroad)

Above: Kenneth Anthony

took these two photos of the gate that constituted the Tower 102

interlocker in its

later years. The gate was normally closed across the Southern Pacific tracks,

allowing continuous movements on the Houston Belt & Terminal tracks. This gate was designed so that when fully closed and locked, trains on

the opposite track would see a signal authorizing them to proceed without delay.

If the gate was unlocked, the signals on the opposite track would warn trains

that they may not proceed through the crossing. Gates were used as a simple

manual control system for tracks that were seldom used, to be opened

only on the rare occasions when a train or maintenance vehicle needed to cross.

John Thomas Brady (sometimes incorrectly referenced as

Thomas M. Brady) was 26 years old when he arrived in Houston in 1856. Born in

Maryland, educated as an attorney, Brady settled at Harrisburg near Buffalo

Bayou and opened a law practice. Seeing Buffalo Bayou on a regular basis no

doubt influenced his thinking that it might one day become a transportation

artery for ocean-going vessels. To capitalize on his vision, Brady bought 2,000

acres of land on April 18, 1866 along the south bank of Buffalo Bayou, north of

Harrisburg, several miles east of Houston. Brady and other investors proceeded

to establish two companies, the New Houston City Company and the Texas

Transportation Company (TTC), to develop Brady's property and build a rail line

to serve it. Their timing was poor; the slow economic recovery after the Civil

War left investors leery of funding these ventures. Very little construction was ever accomplished, and by 1876,

Charles Morgan had bought controlling interest in the TTC. Morgan owned a

large steamship business that dominated shipping in the Gulf of Mexico. He

wanted the TTC for its charter so he could build a rail line along the north

bank of Buffalo Bayou to the new port of Clinton, from which he had paid to dredge

a channel to the Gulf. The TTC opened tracks from Houston to Clinton in late 1876,

a right-of-way (ROW) that remains in use today. Morgan's Louisiana and Texas

steamship and rail operations were eventually acquired and merged

into the Southern Pacific (SP) railroad.

Brady's New Houston City Company

did not succeed so he founded the Magnolia Park Company to develop his land. In

1890, he established the Magnolia Park community on 1,374 acres and built a

large amusement area, Magnolia Park, at Long Reach along the south bank of

Buffalo Bayou at Constitution Bend. Brady planned a railroad that would

ferry passengers between Houston and Magnolia Park, and develop freight

business along the waterway. To this end, he chartered

the Houston Belt & Magnolia Park (HB&MP) Railway on April 2, 1889. The

name captured the dual purpose of the railroad -- function as a "belt" railroad

interconnecting other main lines while carrying passengers to and from Magnolia

Park. The

charter specified that the railroad would be "...located so that it or any part

of it may be used as a belt or connecting line."

Brady's

vision of an integrated rail-served port along Buffalo Bayou was prescient, but

once again, his timing was poor. The industries that used Buffalo Bayou shipping

remained on the north side of the bayou, not the south side near the HB&MP.

The railroad sold passenger excursions to Magnolia Park from Houston, but the

fare volume was insufficient to sustain the railroad; it went into

receivership in 1891. [The appointed Receiver was James A. Baker II, father of

James A. Baker III, U.S. Secretary of Treasury and White House Chief of Staff

under President Ronald Reagan.] Brady died from a stroke in June, 1890, and the courts and

his heirs sorted out his holdings over many years.

Although the HB&MP's

initial construction is not listed in the official records of the Railroad

Commission of Texas (RCT), the definitive source of Texas railroad history, S. G.

Reed's A History of the Texas Railroads (1941)

states that in 1890, the HB&MP "...built six miles of track from Fannin

St. eastward on Commerce Avenue through Magnolia Park to Constitution Bend on

Buffalo Bayou." Reed's description measures a total distance of

roughly five miles. However, an 1891 "Bird's-Eye View" map of Houston shows that

where the line curved northeast toward the park, a branch continued east into

the residential area Brady was developing. If this spur was a mile long, that

would account for Reed's assertion of six miles of construction.

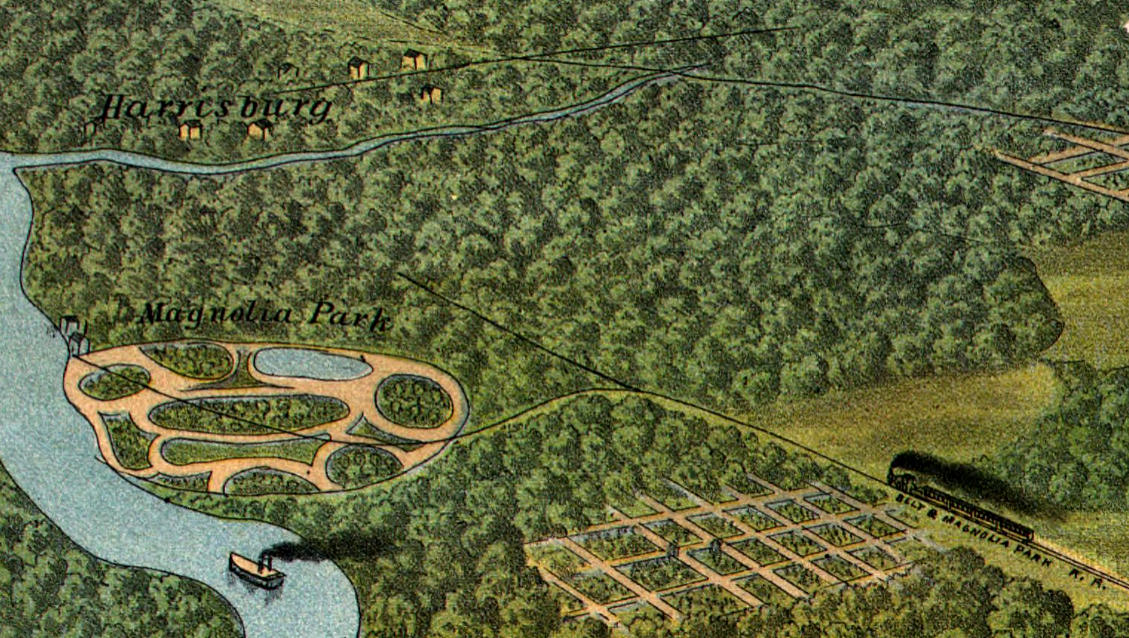

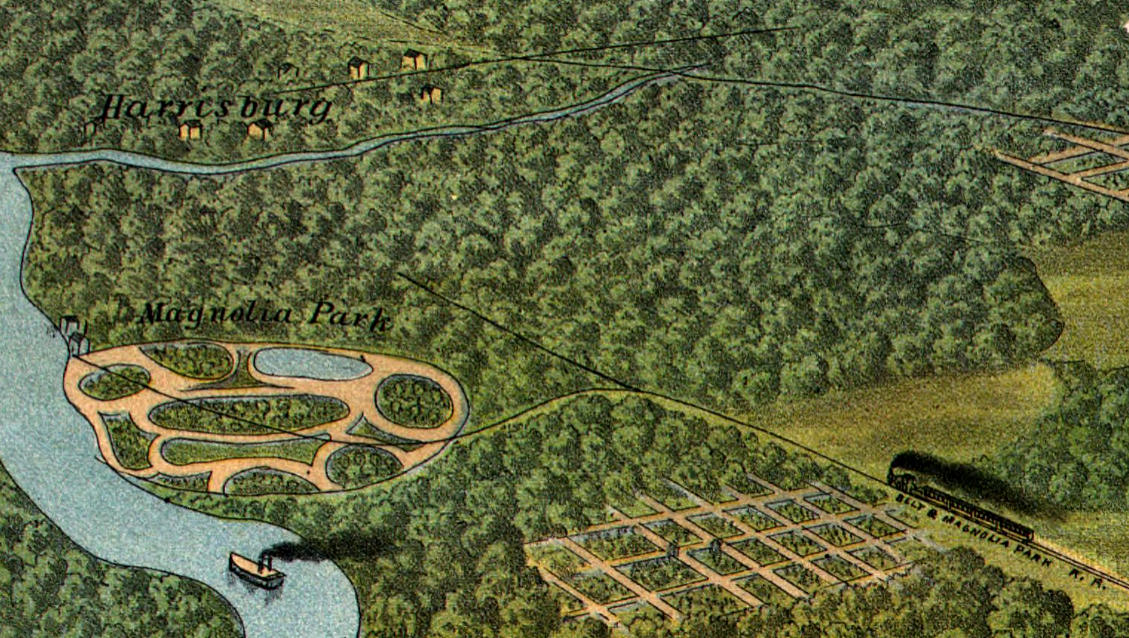

Above: This image is extracted

from an 1891 "Bird's-eye view" drawing of Houston. It faces southeast,

with Buffalo Bayou at left meandering toward Galveston Bay. The town of

Harrisburg is depicted along Buffalo Bayou south of the mouth of Brays

Bayou. The locomotive is going east on the HB&MP, away from downtown

Houston toward a junction where the main line curves to the northeast to

reach Magnolia Park. The rail spur that continues east from

the junction ends abruptly in the area Brady planned to develop as a residential

community. (Library of Congress

image)

The HB&MP was not well-constructed. In

receivership, it faced lawsuits from the city of Houston and other property

owners claiming that it was not compliant with the ordinances that had authorized its ROW. In particular, the city claimed they had only authorized an electric rail line suitable for urban passenger service,

not the steam locomotives HB&MP operated. The HB&MP countered

that the ordinance allowed "...electricity, or such other power as will not

necessarily obstruct the use of said streets by the public...", and that

steam was in common use and met the criteria. As litigation proceeded, the Receiver

made arrangements to allow the International & Great Northern (I&GN) Railroad to

lease portions of the HB&MP for car storage, providing a small but steady

income. In 1894, the Receiver got a better offer; the Galveston, La Porte &

Houston (GL&H) Railway proposed to lease four miles of the HB&MP's track to

reach downtown Houston. As Reed explains, the lease gave the HB&MP "...a

mileage prorate of all revenue. This enabled the Receiver to keep the road

alive...".

The GL&H did not yet officially exist. It was the La

Porte, Houston and Northern Railroad and it was in the process of getting the

legal arrangements in place to change its name, to consolidate various rail lines

between Houston and Galveston, and to build new tracks where necessary. The

authorization was

signed into law on January 23, 1895 as Senate Bill 35, Chapter 7, subtitled

"An act to authorize the La Porte, Houston and Northern Railroad Company to

purchase and acquire and consolidate with it, all the property, rights and

franchises of the North Galveston, Houston and Kansas City Railroad Company and

the Houston Belt and Magnolia Park Railway Company, and to change its corporate

name." The name change to GL&H proceeded immediately with a new

charter dated January 30, 1895, and the purchase of the North Galveston, Houston and

Kansas City Railroad Company was completed a month later. Although authorized to

do so, the GL&H did not purchase the HB&MP, choosing instead to lease four miles

of track into downtown Houston. With this accomplished, the GL&H began to build

the remaining tracks to form a complete line between Houston and Galveston.

The GL&H's primary purpose was to

establish rail competition for the Houston - Galveston market, capitalizing on

their new bridge onto Galveston Island. Two bridges

already existed; one was owned by the Galveston, Houston & Henderson (GH&H),

part of Jay Gould's rail empire that included the Missouri Pacific, the Texas &

Pacific, and various other lines. The GH&H was leased to another Gould

property, the I&GN. The other Galveston bridge belonged to the Gulf, Colorado &

Santa Fe Railway, a component of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway that

was competing with SP for rail dominance in the western U.S. The GL&H's long term

plan was to build a railroad that would be attractive to SP, taking advantage of an odd situation -- the largest railroad system in Texas

(SP)

did not have a bridge to the largest port in Texas (Galveston). But, in early 1896, before their Galveston bridge was finished, the GL&H filed for bankruptcy protection on

January 7, having exhausted its capital in less than a year.

The District

Court appointed

Receivers to take control of the GL&H and selected an independent Master to

review the financial situation and make recommendations. A hearing

was held on January 20, 1896, and three days later, the Master reported to the Court that approximately $300,000 was needed to make the GL&H a viable competitor

for Houston - Galveston traffic. The Court approved the Master's report and

authorized the GL&H Receivers to borrow money by issuing "Receiver Certificates"

for a total not to exceed $250,000. With the authority granted by the Court, the

Receivers proceeded to hire L. J. Smith, a Kansas City construction firm, to

perform much of the work, including completion of the Galveston Island bridge.

|

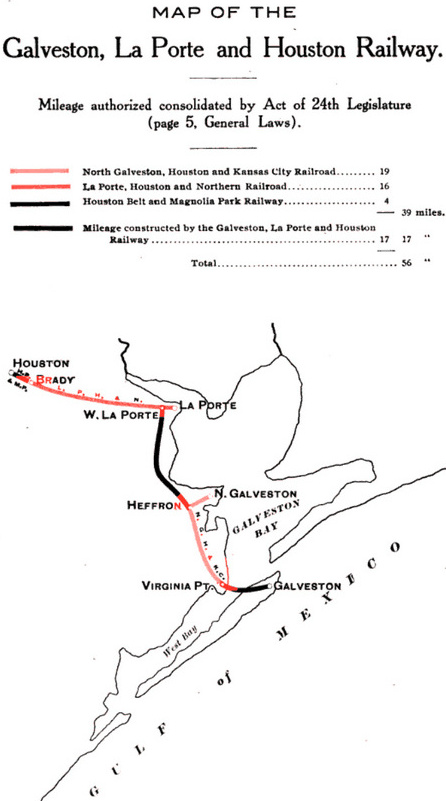

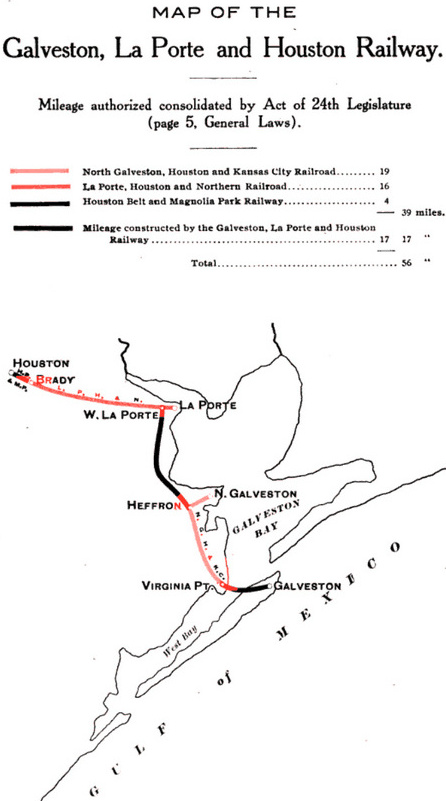

Left: This map appears

in the book Railroad Consolidations in

Texas 1891 - 1903 by Joseph Draper Sayers published in 1903.

Note that the final segment of the GL&H into Houston is from "Brady" on

the HB&MP. Objective evidence for the precise location of Brady, and

whether it differs from "Brady Junction", has not been found.

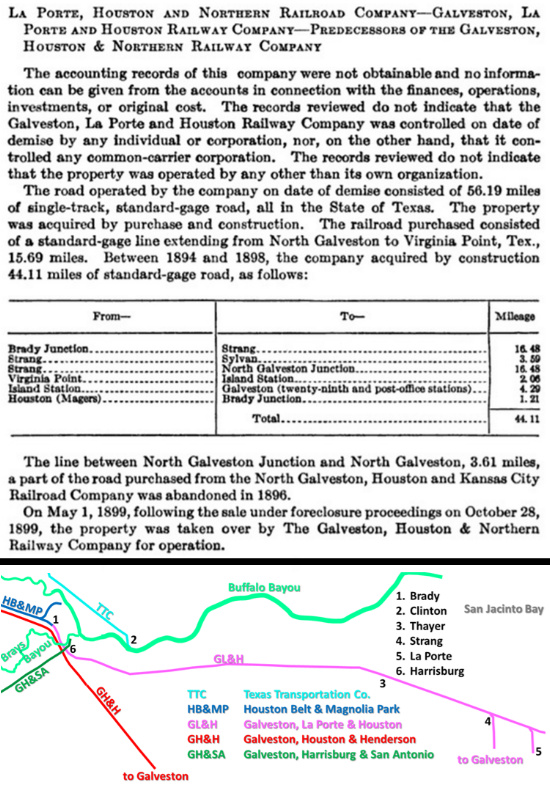

Above Right: This

valuation statement published by the Interstate Commerce Commission in

the 1930s describes the holdings of the GL&H prior to its sale under

foreclosure. The table lists "Brady Junction" in two

places, but no map purporting to show the precise location of "Brady

Junction" has been found.

Below

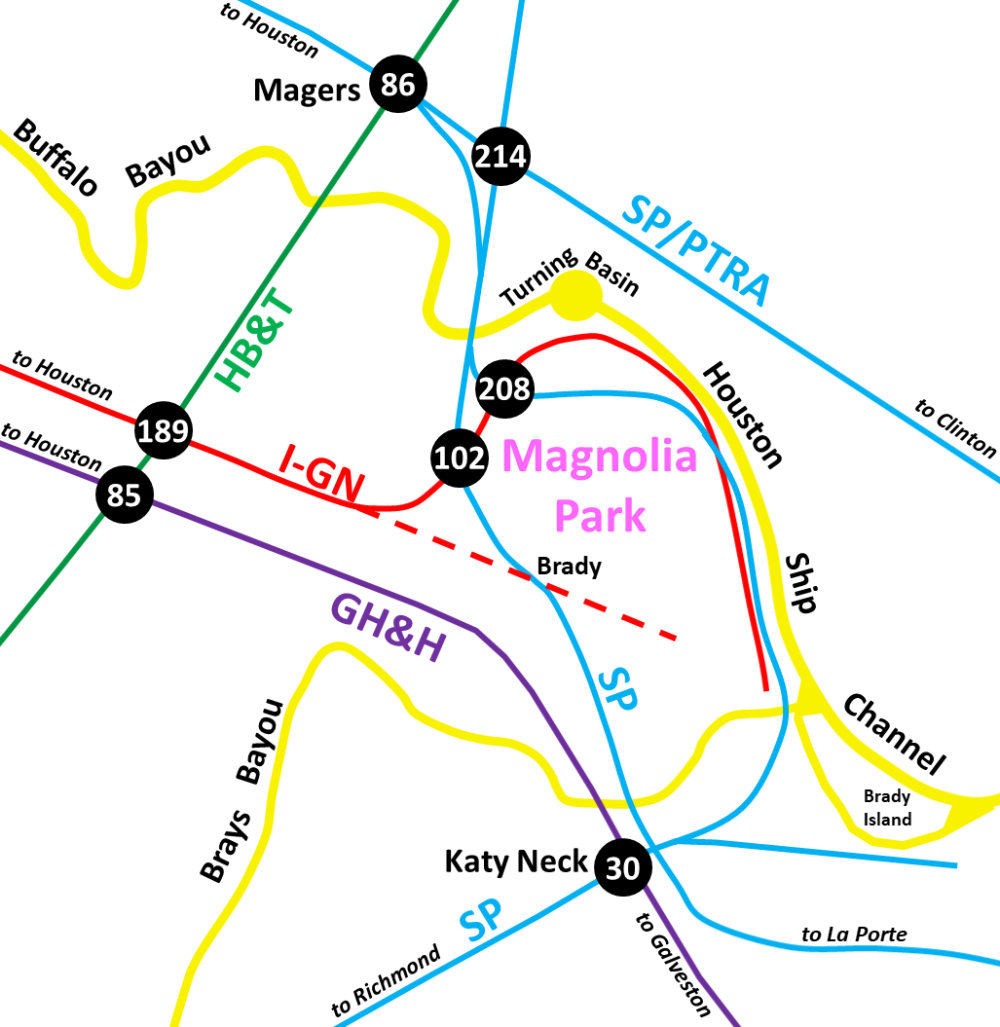

Right: This notional map shows the railroads between

Houston and La Porte that existed in 1895 when the consolidation of the

GL&H took place. The map assumes that Brady was the location of the

connection between the GL&H and the HB&MP. |

|

The 1903 map (above left) states that the HB&MP

provided four miles of tracks for the GL&H route into Houston, and it denotes these

tracks as between Houston and Brady. While the location of Brady has not

been objectively identified, four miles of track is generally consistent with Reed's description of the HB&MP's construction between the intersection of Fannin and Commerce street in downtown

Houston, and the location where the HB&MP tracks curved to the northeast toward the amusement park. But that location also served as a

junction for the HB&MP's eastward spur into the future Magnolia Park residential

area, and it is likely that "Brady" was the location on that spur where the GL&H

tracks intersected the HB&MP.

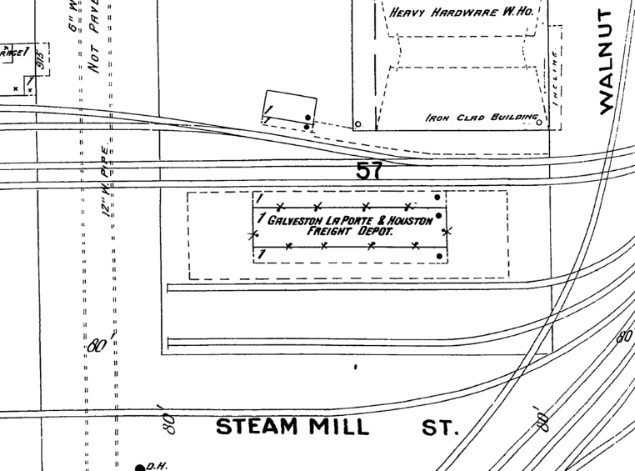

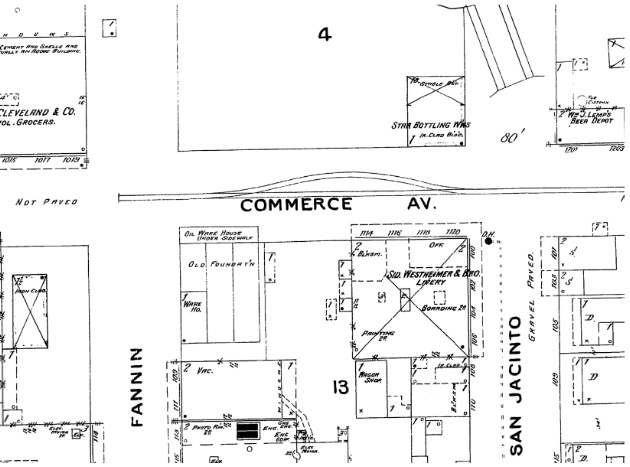

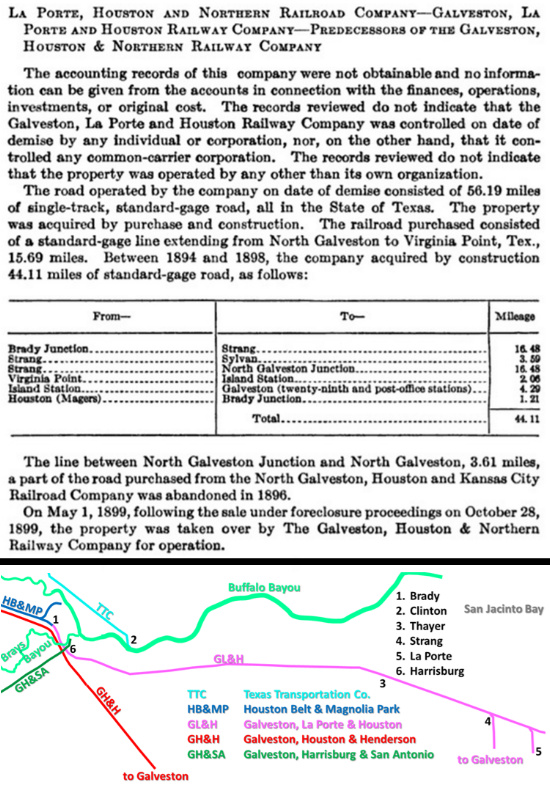

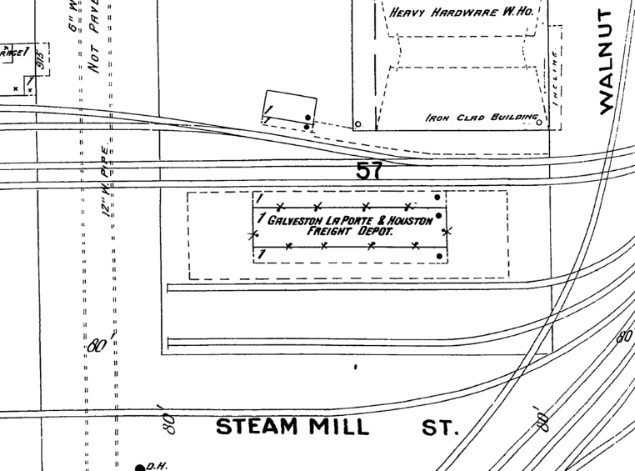

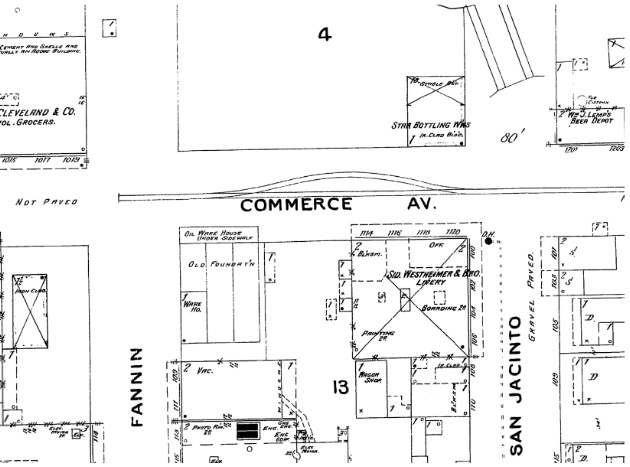

The 1896 Sanborn Fire Insurance

Map of Houston shows the GL&H freight depot on the north side of

Buffalo Bayou close to Bonner's Point. To

reach this depot from south of the bayou, the GL&H would not have needed to

use the entire HB&MP line into downtown Houston at Fannin and Commerce streets.

Instead, they would have turned north near the intersection of Commerce and

Hutchins Street to take a rail bridge shared by SP and other railroads leading over Buffalo Bayou to Bonner's Point

and SP's Houston & Texas Central (H&TC) passenger station. The distance from the intersection

of Commerce and Hutchins St. east along the ROW to the HB&MP junction where its

main line curved northeast is about 3.5 miles. Continuing east on the HB&MP spur

another half mile brings the total distance to four miles near the intersection of

75th St. and Avenue B. This theory accounts for the four miles assigned to the

HB&MP tracks on the GL&H map above, and it's consistent with the fact that the

GL&H tracks from Harrisburg across Brays Bayou into Magnolia Park passed through

the intersection of 75th St. and Avenue B. This was where the two railroads

intersected and it is the most likely location for "Brady".

Unfortunately, this theory conflicts with Reed's declaration

that the HB&MP's lease was "...four miles of its track from Brady St. to

Fannin St. ...". There are several problems with Reed's description. First and

foremost, Brady St. was essentially the same as Commerce

Ave. as it passed east of Milby St. A map from 1920 shows the name changed at Milby St., but

current maps show Commerce retaining the name for a short distance east of Milby

St. At minimum, the HB&MP ROW was on Brady St.

between its intersections with Drennan St. and Jenkins St., a distance of less

than 1,200 ft. Regardless of where on Brady St. Reed was referencing as the

beginning of the four mile lease, the distance along the HB&MP ROW

west to Fannin St. is only about two miles,

just half the distance that the lease reportedly covered. More significantly,

there would be no way for the GL&H to actually reach the HB&MP

on

Brady St. without also traveling on the HB&MP east

of Brady St. at least 2.5 miles to a location where the GL&H could intersect the existing tracks,

specifically the intersection of 75th St. and Avenue B. And finally, actually

going all the way to Fannin St. would serve no purpose for the GL&H because

(with all due respect to Mr. William J. Lemp, as explained below) there was literally nothing there! The tracks ended in the middle of the

intersection of Commerce and Fannin, without any depot located nearby and with

no means to turn a train around. While this might have been marginally acceptable for

the HB&MP's modest attempt to serve park excursion passengers from downtown

Houston, it certainly would not work for a railroad that was planning to offer

competitive passenger and freight service between Houston and Galveston. Note,

however, that Reed's

statement becomes almost completely correct if the "St." is dropped after

the word "Brady", i.e. "...four miles of its track from

Brady to Fannin St. ...". This assumes, consistent with the GL&H map above, that

Brady was the location where the two rail lines intersected. Reed's statement

becomes "almost" correct because the GL&H did not need to operate all the way to

Fannin St. Four miles of track west from Brady

was precisely enough to reach the rail junction near Commerce and Hutchins that led to the GL&H

depot north of Buffalo Bayou via the shared bridge. That the HB&MP ROW passed

through "Brady" but also operated on "Brady St." appears to have led to the

confusion.

1896 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map of Houston

Above Left: The

GL&H freight depot was north of Buffalo Bayou near the intersection of

Steam Mill St. and Walnut St., about 500 ft. northeast of the future

Tower 108 (commissioned in 1918) at Bonner's Point. Both streets

still exist but no longer intersect. The GL&H used the H&TC passenger depot which was also north of Buffalo Bayou.

Above Right: The HB&MP tracks ended literally in the center of the

intersection of Fannin and Commerce in downtown Houston, without a wye or a depot in sight

(unless you count "Wm. J. Lemp's Beer Depot" at the northeast corner of Commerce

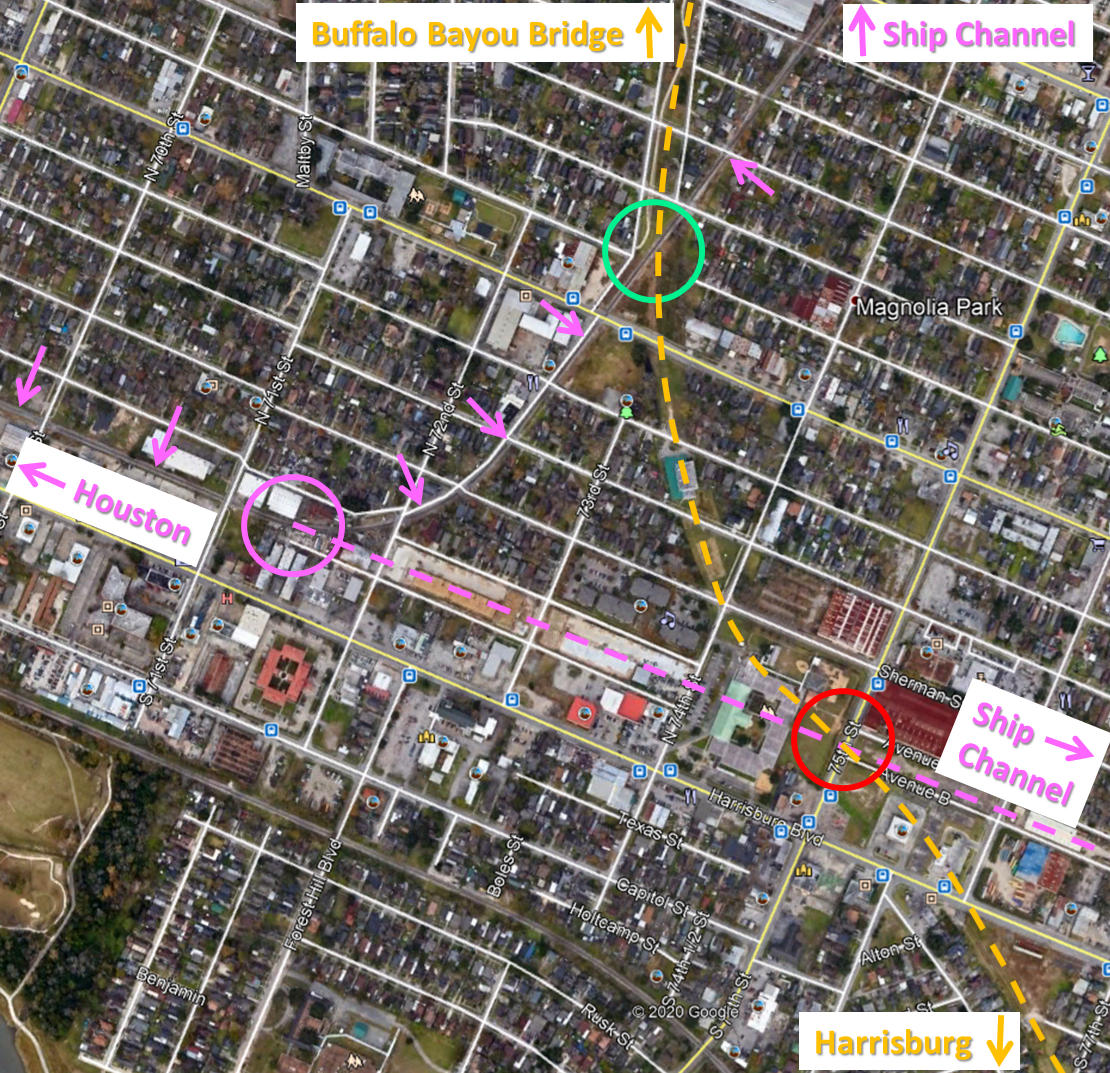

and San Jacinto!) Below: This

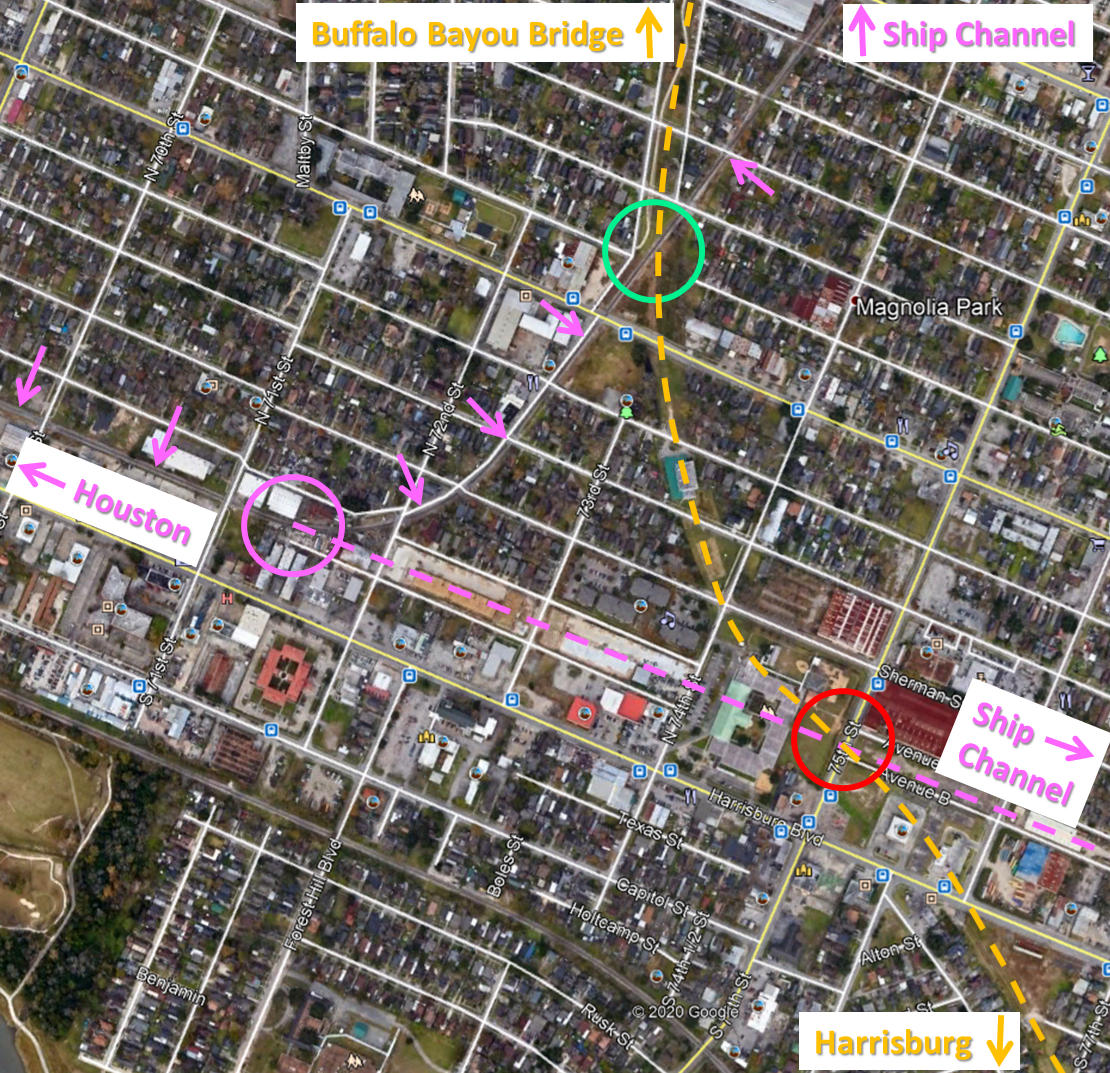

annotated Google Earth image shows the rail connections and crossings in

Magnolia Park, with dashed lines used for tracks that are no longer intact, and

pink arrows for tracks that continue to use the HB&MP ROW. The red circle shows

the presumed location of Brady where the GL&H, coming north (orange dashes) from

Harrisburg, intersected the HB&MP extension (pink dashes) that ran east from

the HB&MP junction (pink circle). The GL&H did not stop at Brady; their

construction continued north, crossing the HB&MP at the future Tower 102

(green circle) and continuing to a new bridge over Buffalo Bayou. The HB&MP

continued northeast from the Tower 102 crossing toward the original Magnolia

Park amusement area. After the demise of the HB&MP, those tracks became valuable

for servicing industries along the south bank of the Houston Ship Channel. At

some point, the HB&MP ROW through Brady was extended east (from the red

circle) to the Ship Channel

to provide an alternate route for servicing the Port of Houston, but the tracks

were subsequently removed.

Although not marked, the tracks on the former GH&H ROW are visible in the lower

left quadrant of the image.

It's likely that Brady was the junction of the GL&H

and the HB&MP at the intersection of 75th St. and Avenue B, but confirming this

idea is not straightforward. There are RCT

construction records that mention Brady, but they are not particularly

enlightening. For example, RCT lists 4.07 miles of construction for the HB&MP in 1895 between

Houston and Brady. Notwithstanding the fact that the HB&MP was in receivership

at the time and in no financial position to be doing any construction on its

own, this is probably a report of the rehabilitation of the HB&MP's tracks

to support the lease, presumably funded by the GL&H. It may also reflect a

realization by the GL&H that the original HB&MP construction in 1890 was never reported to

RCT. Either way, it says little about the actual location of Brady.

For 1895, RCT records list two construction activities by the GL&H:

5.76 miles between "0.5 mi. E. of Thayer" and La Porte, and 1.7 miles between

Harrisburg and Brady. Both of these activities were cited in a small article

about the GL&H in the industry periodical Railway

Review in 1895. The article mentions that "Tracklaying between Thayer

and La Porte is now in progress. The contract let to L. J. Smith of Kansas City,

mentioned last week, calls for the construction of two miles of road between

Magnolia Park and Harrisburg, including a bridge over Bray's Bayou...".

This construction gave the GL&H the connection they needed to use the HB&MP's

tracks into downtown Houston from Brady. It was a northern continuation of

GL&H's prior construction of 12 miles of track between "0.5 mi. E. of Thayer"

and Harrisburg that was reported to RCT in 1894 by the La Porte, Houston and

Northern, their previous corporate name. Since the GL&H had leased the four

miles of HB&MP tracks west from Brady in 1894, it is reasonable to assume that

the rehabilitation of the GL&H tracks had been completed by the time this

construction north from Harrisburg reached Brady, hence service to Houston could

begin immediately. Without knowing specifically where in Harrisburg the

construction began, a distance of 1.7 miles to Brady is certainly within the

realm of possibility, and tends to favor the idea that Brady was a name for the

location where the two railroads intersected. It may also have literally been

John T. Brady's homestead at some point in time.

The Master's

plan also allowed the construction from Harrisburg to Brady to be extended north through Magnolia Park to a new bridge over Buffalo

Bayou, adjacent to what is now the Turning Basin of the Houston Ship Channel. Thus,

the

GL&H tracks intersected the HB&MP twice, once at the HB&MP spur

(Brady, presumably) and

again at the HB&MP main track, later interlocked as Tower 102. There is no doubt that the effort to build to the

north side of Buffalo Bayou was to a large extent a

result of the GL&H's discussions with SP. At the time, SP was negotiating to use the new GL&H

bridge onto Galveston Island. SP owned several

railroads that served industries north of Buffalo Bayou, but those lines

had no direct route to Galveston (and since the Houston Ship Channel did not yet

exist, the Port of Galveston remained important.) With the GL&H

having completed consolidation of tracks and construction of missing segments

between Harrisburg and Galveston during 1895, continuing the Harrisburg - Brady

tracks north through Magnolia Park and

across Buffalo Bayou would allow SP's north side railroads to offer

direct service to the Port of Galveston. Presumably, the former connection at

Brady became a switch so that the tracks under lease from the HB&MP could be

accessed in addition to the new route north to Buffalo Bayou. Perhaps this

caused "Brady" to also become known as "Brady Junction". Looking back, it is apparent

that the long term plan to entice SP into a relationship to serve their

railroads north of Buffalo Bayou into Galveston explains why the GL&H leased the

HB&MP instead of buying it. North of the bayou, SP tracks could be used to reach

the GL&H freight depot and the SP passenger depot in downtown Houston. In

essence, the HB&MP lease was just an

expedient means to get a presence into downtown Houston pending construction of the

new Buffalo Bayou bridge and final negotiations with SP.

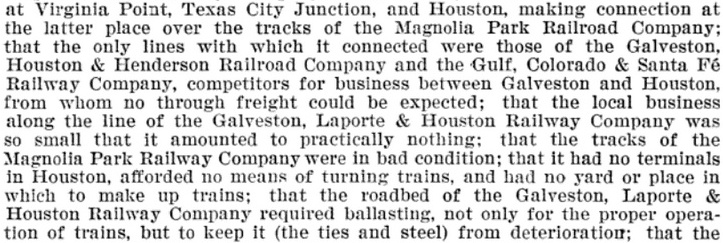

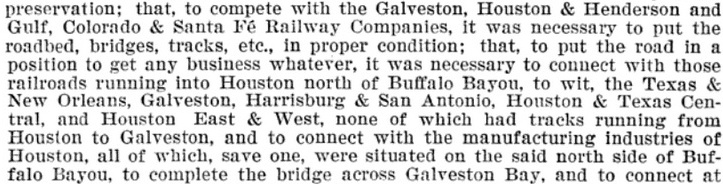

It didn't take long for GL&H's

creditors to sue the company for non-payment of Receiver Certificates. After a

ruling in Federal District Court, the case went to the Fifth U.S. Circuit

Court of Appeals in 1900. The published decision of the Appeals Court included

a lengthy description of the sad state of the GL&H at the time it began

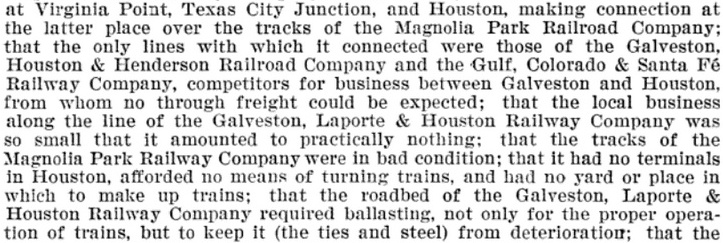

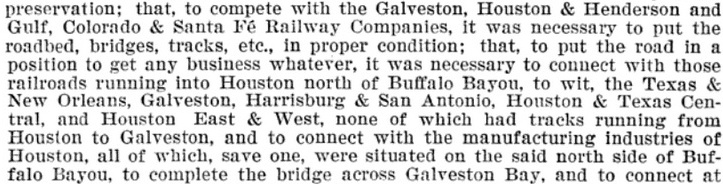

operations over the HB&MP. The Court explained (Federal Reporter, 1900) that the

GL&H's only connections were...

"...bridges

along its line needed repairing..." along with numerous other maintenance

issues. The Court discussed the rationale for borrowing money to build a bridge

across Buffalo Bayou, even though, at the time of receivership, the Galveston

Bay bridge had not yet been completed. The Master's report had insisted that

completing the Galveston Bay bridge was necessary for its...

"...Galveston

with the tracks of the Galveston Wharf Company..." was essential to having

any business at all. Later in the ruling, the Court looked back at the justification

for building north across

Buffalo Bayou, quoting from the District Court's decision...

"While the result shows that the road under the receivership was operated at

a heavy loss, even after its extension and completion, yet 95 per cent of the

business done by it was derived from those railroads and manufacturing

industries on the north side of Buffalo Bayou, in Houston, with which there

could have been no connection, and consequently there could have been no

opportunity to get business, unless the extension across Buffalo Bayou had been

made."

In 1897, SP President C. P. Huntington offered to buy the

GL&H from the Receiver. Railway Review

reported in its March 20, 1897 edition... "An offer has been made, so it is

reported, by Mr. C. P. Huntington for the purchase of the Galveston, La Porte &

Houston, and while nothing definite concerning the matter is known, it is

thought the offer will be accepted. The price offered is said to be $1,000,000.

This is taken to be a confirmation of the promise made by the Southern Pacific

some time ago to make Galveston one of its principal gulf ports. The G. L. P. &

H. is 53 miles in length running from Brady Junction to Galveston." But the

sale did not take place, for undetermined reasons. Instead, on July 6, 1898, the

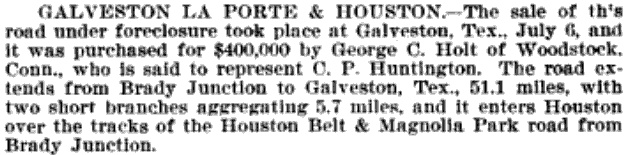

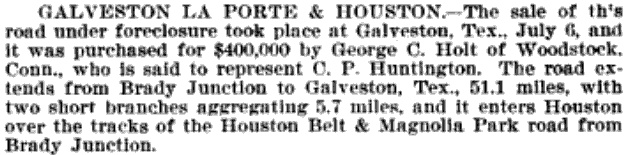

GL&H was sold for $400,000. Volume 26 (July-December 1898) of

The Northwestern Railroader and Railway Age

reported the sale:

C. P. Huntington finally got what he wanted, at a

better price albeit through an intermediary. Given the lawsuits that were

pending against the GL&H, the reason for the intermediary's

involvement was undoubtedly to protect SP from corporate liability. It is

somewhat problematic, however, that both of the above periodical citations

reference Brady as a GL&H endpoint, even though by the

time of the first one, March, 1897, the GL&H had already been extended across

Buffalo Bayou. Furthermore, there are no RCT construction records

for any railroad in the 1896-1899 timeframe

that could be candidates to have included the Buffalo Bayou bridge construction

(the three GL&H records for 1896 are all for construction south of Strang.)

Hypothetically, the 1.7 miles of construction from Harrisburg to Brady in 1895

could be stretched to fit, but the endpoints would be neither Brady nor

Harrisburg. From the south bank of the GL&H's Brays Bayou bridge to the north

bank of the GL&H's Buffalo Bayou bridge is approximately 1.92 miles. This

does fit, however, with the Railway

Review commentary in 1895 "...the construction of

two miles of road

between Magnolia Park and Harrisburg, including a bridge over Bray's Bayou...".

[emphasis added]

Although the

GL&H was technically out of receivership with the sale to George C. Holt in July, 1898, the GL&H's advertisement for the November,

1898 edition of Official Railway Guide had

already been submitted for publication. It still showed T. W. House as Receiver.

More significantly, this timetable into Houston included a stop at "La Porte

Junction", a mere 3.9 miles from Bonner's Point

near downtown Houston.

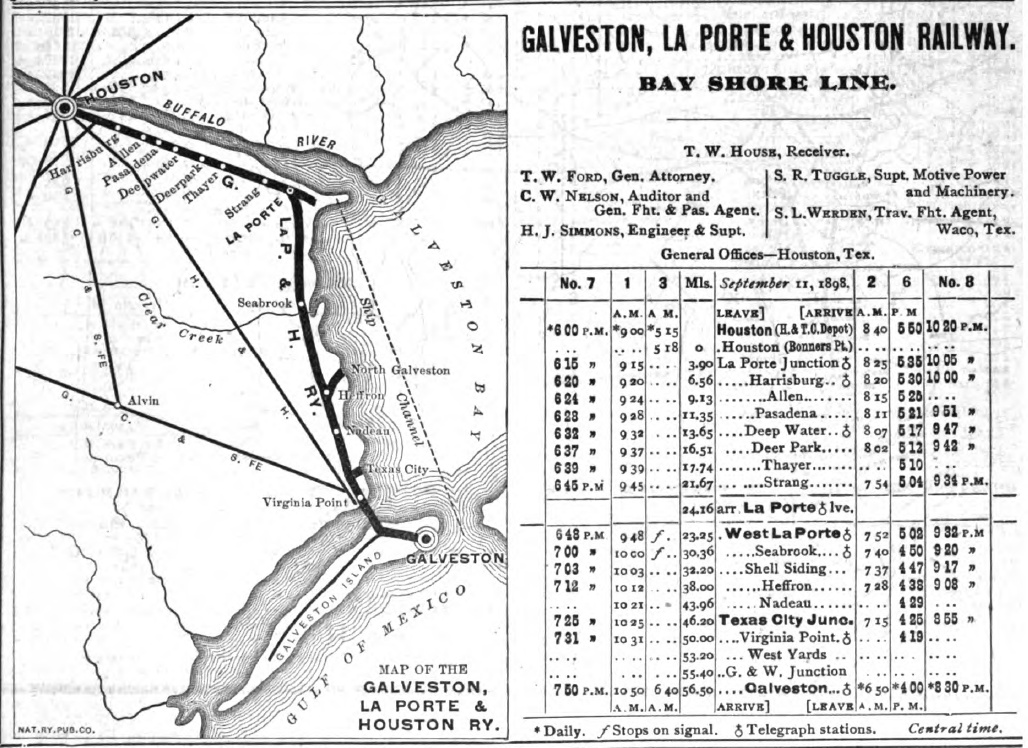

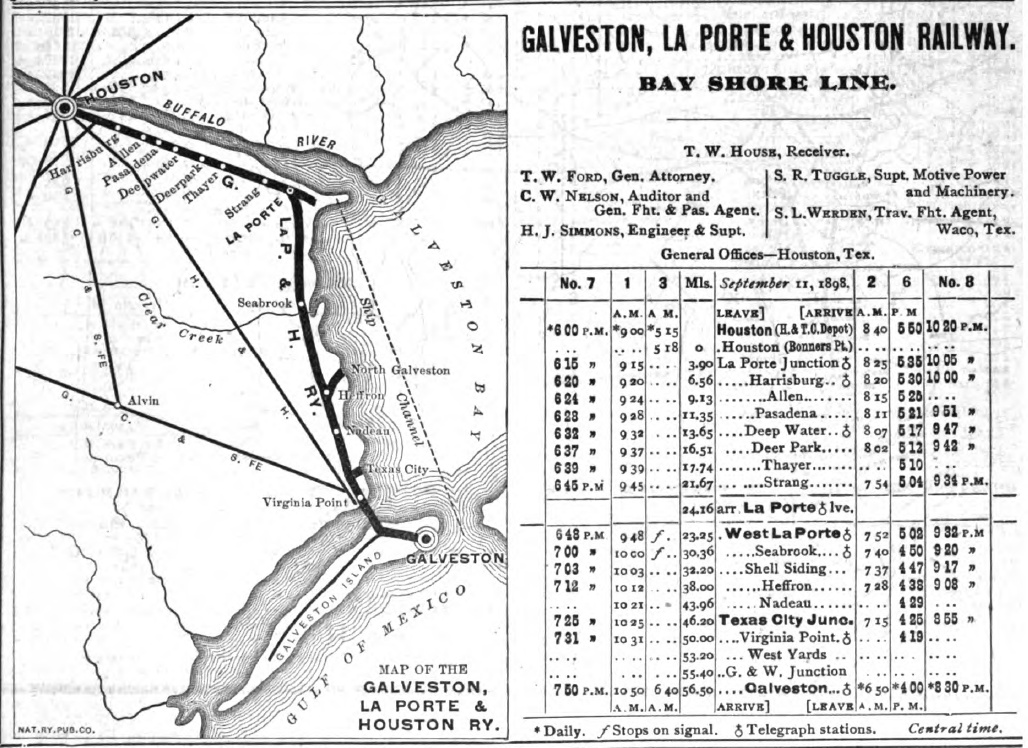

Above: Notwithstanding the

significant creative license exercised in drawing the map, this GL&H advertisement in

the November, 1898 edition of Official

Railway Guide can be presumed to present an accurate timetable for that

date. It

shows a stop at La Porte Junction which was just beyond the north end of the GL&H bridge over Buffalo Bayou (despite the

map showing the route always south of the "Buffalo River".)

Today, "La Porte Junction" is more commonly

known as "Galena Junction" located immediately

north of the GL&H bridge over Buffalo Bayou. It was, and remains, an important

junction for rail movements along the north side of Buffalo Bayou. The passenger

stop at La Porte Junction indicates that the GL&H was no longer using the HB&MP

tracks from Brady into downtown Houston for passenger service. Instead, GL&H trains coming north from

Harrisburg would continue past Brady, cross the HB&MP at the future Tower 102,

and then cross the GL&H's Buffalo Bayou bridge to La Porte Junction. From there,

trains proceeded west on existing SP tracks past Bonner's Point to the H&TC passenger depot (noted in the

advertisement) which was located at Washington Street. It is likely that the

GL&H had begun using this passenger service routing as soon as the Buffalo Bayou

bridge and the tracks to La Porte Junction were completed. They were presumably

getting favorable rates for the use of SP's tracks and passenger depot (in

exchange for SP's use of GL&H's Galveston Island bridge), and it

allowed them to phase out their lease of the HB&MP.

In 1897, Poor's Manual of Railroads -

Southwestern Group stated that the HB&MP had been sold for $10,000 to "M.

Young", a Chicago investor, and that it was being operated under contract by the

GL&H. While there were undoubtedly legal arrangements for the GL&H's lease of

the HB&MP, there's no other evidence that this transaction actually occurred.

Neither Reed nor the Handbook of Texas reference "M. Young"

in association with the history of the HB&MP. Reed does state, however, that the HB&MP was reported

to have been offered to SP for $10,000, but SP declined. Instead, all sources

agree that the HB&MP was sold by the Receiver to Herbert F. Fuller for $9,100 on

November 1, 1898. Six months later, Fuller transferred the property to the newly

chartered Houston, Oak Lawn & Magnolia Park (HOL&MP) Railway, of which he was a

Director. Shortly thereafter, the HOL&MP was sold to the I&GN. The HOL&MP

operated passenger service under their name; I&GN handled all freight service on

the line.

It's clear that I&GN was working with Fuller to create a

railroad to acquire the HB&MP. Again, corporate liability related to various

pending lawsuits against the HB&MP may have led I&GN to acquire the property

through a subsidiary. I&GN valued the property with the same vision that

motivated Brady to build it; ocean-going ships would someday

traverse Buffalo Bayou up to Constitution Bend, and industries would populate the south bank as

was already happening on the north bank. I&GN

later built tracks along the south bank all the way to the mouth of Brays Bayou. The city of Houston owned some of this land and established the

Port of Houston, served by I&GN.

On October 4, 1898, L. J. Smith, the

Kansas City contractor who had built much of the GL&H, was able to foreclose on

the railroad for non-payment. The GL&H was then operated by a Trustee until it

could be sold to a new ownership group. In March, 1899, the Galveston, Houston &

Northern (GH&N) Railway was chartered to acquire the GL&H, with Smith becoming a

GH&N board member. The sale was completed in April and the GH&N began operating

the GL&H's routes and trackage rights arrangement with SP. The GH&N ownership

group had been assembled by SP (again, likely for corporate liability reasons

while remaining court cases were settled.) SP management operated the

GH&N even though it was an independent railroad.

RCT has a construction

record for 1900 stating that the GH&N built

1.2 miles between Brady and Magers (the future

Tower 86). Again, this is somewhat problematic

since tracks had already extended past Brady well before 1900. The fact that

Magers was listed as an endpoint may indicate that these tracks were built to

bypass La Porte Junction, i.e. this may

have simply been an expedient to avoid congestion at La Porte Junction since

GH&N passenger trains depended on this route. It's also possible that this

was some kind of delayed report (instigated by SP) of the construction north

from Brady across Buffalo Bayou that had occurred earlier but was never reported

to RCT. Also, the term "Magers" is not well-defined; it has always been

associated with the location of Tower 86, but otherwise, the origin of the name

"Magers" is lost to history, i.e. it may have encompassed a larger area, not

just the Tower 86 junction. The GH&N officially became part of SP

when a state law was passed in 1905 allowing SP to acquire it and assign its

assets to one of its Texas railroads, the Galveston, Harrisburg & San Antonio

(GH&SA). The GH&SA had long been involved in shipping on Buffalo

Bayou, getting its start at Harrisburg when it was the Buffalo Bayou, Brazos and

Colorado (BBB&C) Railway chartered in 1850, the first railroad in Texas.

Prior to

acquiring the GL&H, SP had determined that it needed another bridge over

Brays Bayou to reach the port that was rapidly developing along the south bank

of Buffalo Bayou. The planned bridge was approved by the Secretary of War on

January 13, 1903, but the bridge was not built. In 1915, SP built a 50 ft. plate

girder lift bridge at the mouth of Brays Bayou. This allowed SP to gain access

to various port industries in competition with I&GN without having to circle

through the north side of Magnolia Park. Eventually, SP tracks went north along

the waterway all the way from their new bridge over Brays Bayou to their

bridge over Buffalo Bayou. This helped bring the demise of SP's route through

Tower 102 since SP did not need two routes between Harrisburg and Galena

Junction and the Tower 102 route did not serve any industries.

In 1917, the city of Houston decided that it

needed its own bridge over Brays Bayou, presumably in support of mass transit for

the port's workforce. This was reported by Electric

Railway Journal to be part of a proposed 4-mile municipal rail line from

near the Port of Houston to the Sinclair refinery east of Harrisburg. A 1917

issue of Texas Trade Review posted this notice: "Houston, Tex., Bridge -

City Secretary will receive bids until noon February 11, for railroad plate

girder bridge over Brays Bayou for Houston Municipal Railway. Plans and

specifications on file with E. E. Sands, city engineer. Usual rights reserved."

The bridge was built about 750 ft. upstream of SP's lift bridge. SP's lift

bridge was removed sometime in the 1950s, and they began using the former

electric railway bridge which was no longer in use for transit.

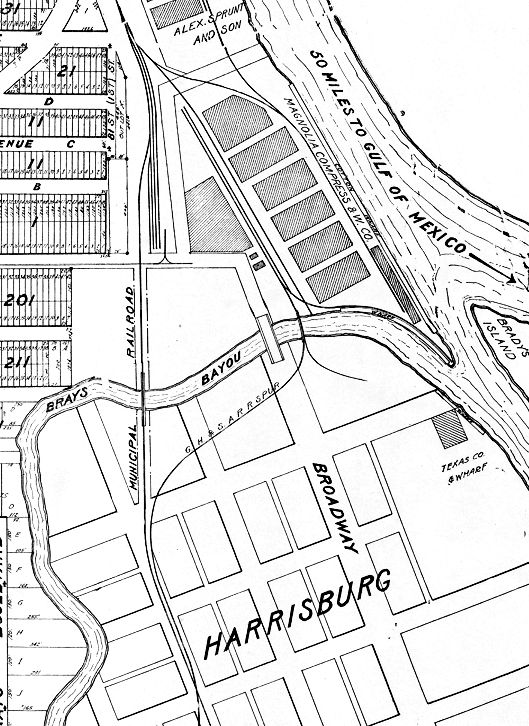

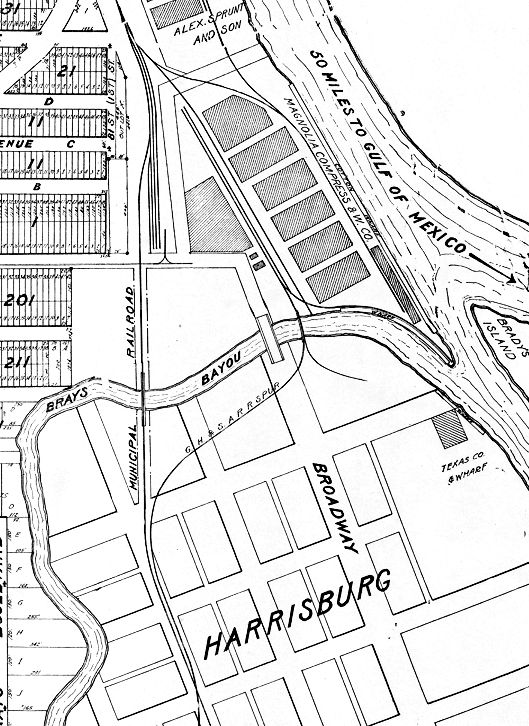

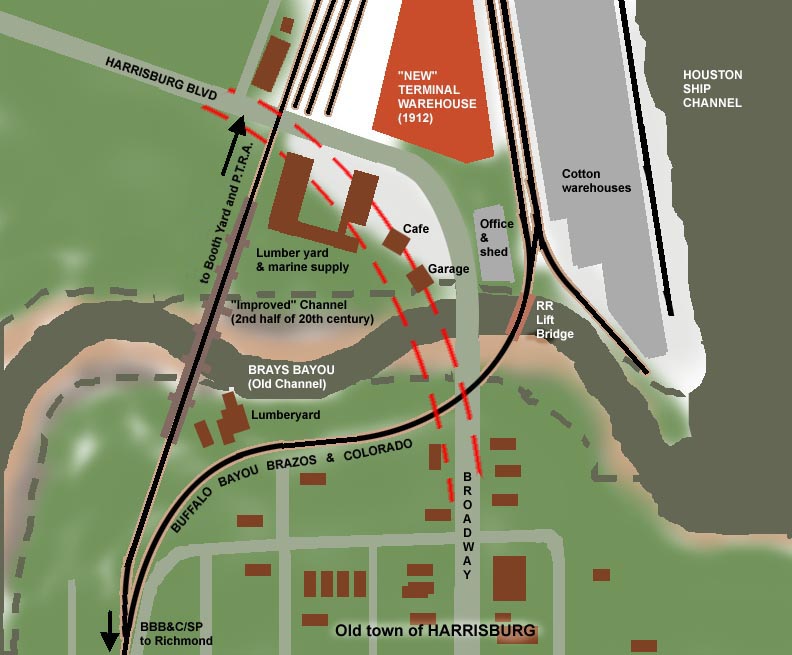

Above Left: This image is

taken from a 1918 map of Magnolia Park (Univ. of Houston Digital Library)

showing the two rail bridges near the mouth of Brays Bayou. The lift bridge was

east of Broadway and no longer exists. The Municipal Railroad bridge remains

intact and

is used by PTRA. Above Right:

Kenneth Anthony supplies this graphic showing how Harrisburg Blvd. and the Brays

Bayou channel have been revised over the years.

The hurricane of 1900 that obliterated much of Galveston, including two of

the three rail bridges (only Santa Fe's survived), put renewed emphasis on the value of establishing

a "Houston Ship

Channel" as a protected deep-water port. The railroads responded to the

development by establishing the Houston Belt & Terminal (HB&T) Railway in 1905

to coordinate freight movements around Houston and to build a new Union Station

for passenger traffic. The HB&T's founding railroads contributed various tracks

around Houston; for I&GN, this included the former HB&MP tracks along the south

bank of Buffalo Bayou. By 1924, the growth of industrial trackage along the ship

channel motivated the creation of the Port Terminal Railroad Association (PTRA)

to coordinate port-related movements and guarantee port access to all railroads.

Over time, rail traffic through Magnolia Park increased substantially. The former GL&H/HB&MP crossing,

now a GH&SA/I&GN crossing, was becoming a bottleneck. As a non-interlocked

grade crossing of two railroads, all trains were required to stop before

proceeding across the diamond. The decision was made to interlock the crossing,

and it was authorized for service as Tower 102 on March 31, 1915, reported by

RCT to have an

8-function mechanical interlocker.

|

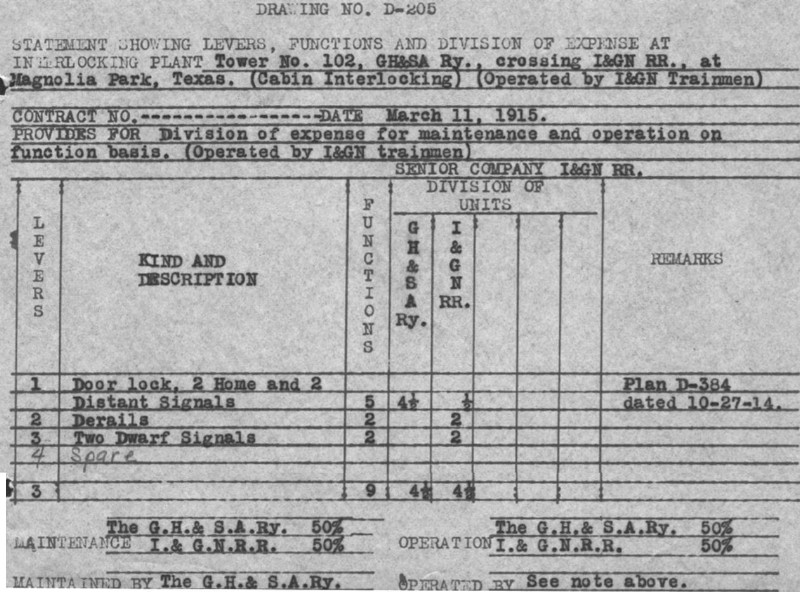

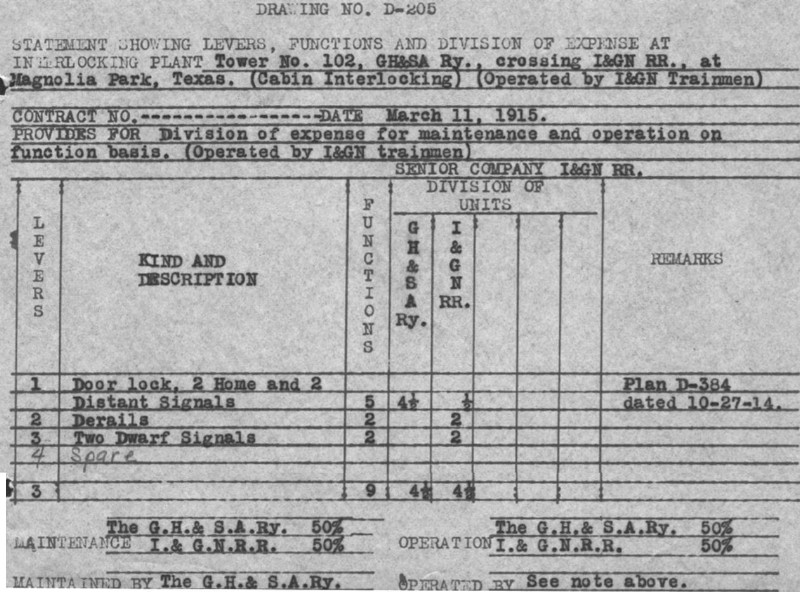

Left: Two weeks before RCT authorized Tower 102

to be placed in service, this interlocker drawing (from SP's archives,

courtesy Carl Codney) was finalized on March 11, 1915. It shows that a

Magnolia Park interlocking plan existed as early as October 27, 1914.

This plan defines Tower 102 as a cabin interlocker, typically used to reduce expenses where a busy line crossed

a lightly used one. Instead of a manned tower, the interlocker controls were in a trackside cabin and normally

were set to signal trains on the busier track

to proceed. When a train on the lightly used track needed to cross,

a trainman entered the cabin to set the controls to signal approaching trains on the busier

line to stop. After his train crossed, he reset the

controls to permit unimpeded operations on the

busier line. Because the Tower 102 cabin was "Operated by I&GN Trainmen", the

signals were normally lined to allow continuous movement on the GH&SA tracks.

This is not surprising; SP was still building its new Brays Bayou

bridge, so their Galveston traffic from north of Buffalo Bayou went

through Tower 102.

Note that RCT's initial report of 8 functions was incorrect from the outset; it

was always 9 functions which RCT corrected in its 1923 list.

There are three clues in this drawing that

suggest Tower 102 had been planned originally as a manned tower. Generally, no

division of operation expenses is listed for a cabin interlocker since

the cabin is not manned; train crews operate the controls as part of

their regular job duties. Yet, this drawing shows operating expenses

divided equally between the two railroads, followed by "See note above."

to explain that actually, I&GN trainmen would be operating the controls

(hence, no tower staffing costs to split.) Also, "(Cabin

Interlocking)" and the twice-appearing "(Operated by I&GN Trainmen)" are parenthetical, as if they were

explanatory amendments to an original drawing. |

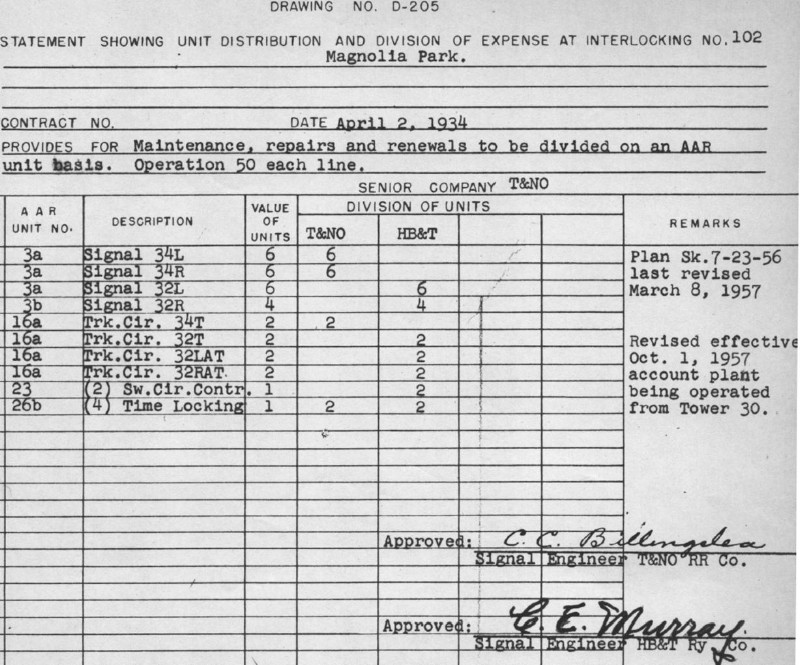

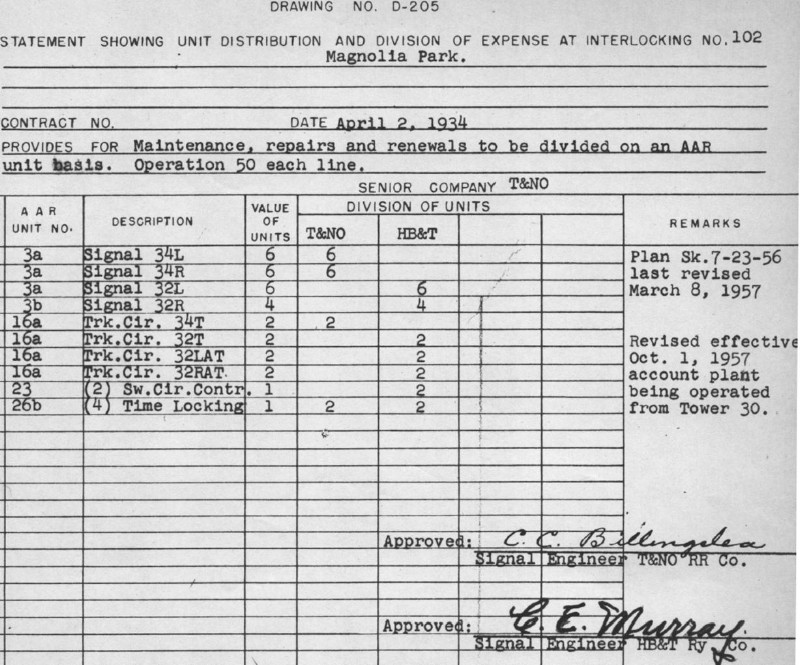

Right: This plan for Tower 102

(obtained from SP, courtesy Carl Codney) was a redrawn and revised

version beginning April 2, 1934 when the interlocker was converted to an automatic

plant. The GH&SA's participation was replaced

by the Texas & New Orleans (T&NO) Railway, SP's principal operating railroad in Texas

which had leased the GH&SA in 1927 (and then formally merged it in 1934.)

The I&GN's participation was replaced by the HB&T, which had taken over

responsibility for what became known as their Magnolia Branch.

On July

23, 1956, the interlocker plan was revised with a new sketch ("Sk.") of

unknown changes. The plan was then updated on March 8, 1957 to

conform to the new sketch. The 8 month period between the finalization of the

sketch and the implementation of the plan may indicate that construction

work was required, which might be related to a known connecting track

at the crossing.

On October 1, 1957, the document was

updated to show that Tower 30 had taken over

responsibility for remote control of the Tower 102 interlocking plant. Sometime

later, the remote control was removed and a manual gate was installed

(photos at top of page.) |

|

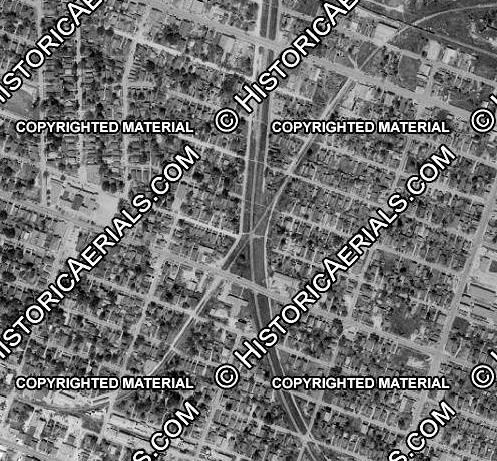

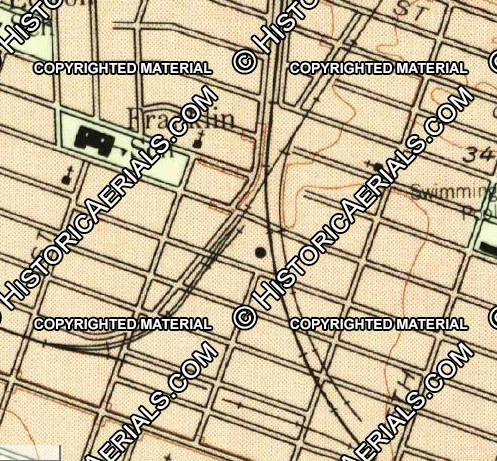

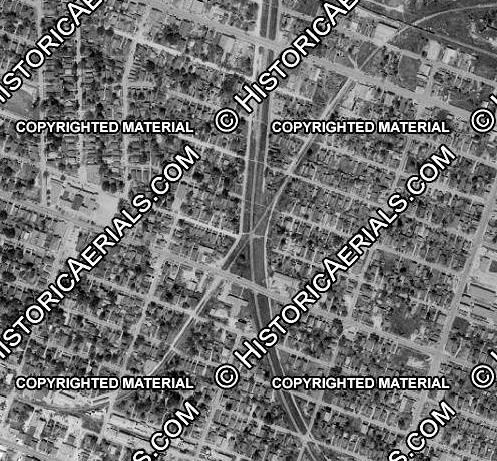

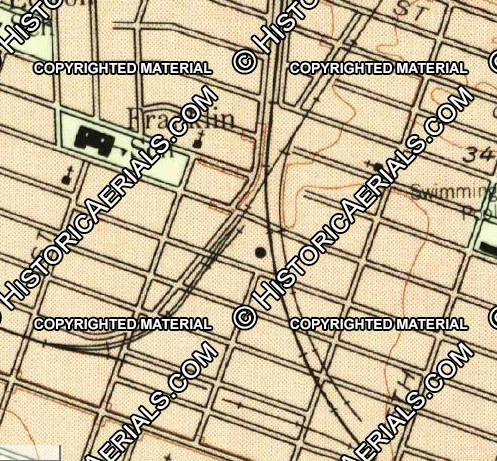

Above Left:

This aerial view of the Tower 102 crossing in

1957 ((c)historicaerials.com) reveals that there was a spur track in the

east quadrant that allowed I-GN trains to travel between the port area and another

yard to the south. (I-GN had become the new moniker when the name changed to

International - Great Northern coming out of bankruptcy in the early 1920s.) Above Right:

This 1957 USGS topographic map corresponding to the image at left shows that the

spur track ended southeast of Tower 102 at a location that (as of 1948)

was owned by Southwest Fabricating and Welding Co. Whether this track was in

place to serve that facility or perhaps serve as a railcar storage area is

unknown. Today, Gallegos Elementary School occupies that site. The map also

shows that this spur track did not intersect SP's tracks. Historic imagery suggests

that the spur track might still have been in place in 1989, but it was

definitely gone by 1995. Note also that the original HB&MP spur that ran from

the main track to Brady and beyond was no longer intact by 1957. The topographic

map shows a break in the middle, creating two spurs served from either end.

Below: These two images of

Tower 102 taken in 1957 (left) and 1962 (right) appear to show the installation

of an equipment cabinet between those dates. The cabinet casts a distinctive square

shadow in the later image. This may have been

related to providing a remote control system for the Tower 30 operator in late

1957. The I-GN spur track discussed above is visible in both images east of the

crossing.

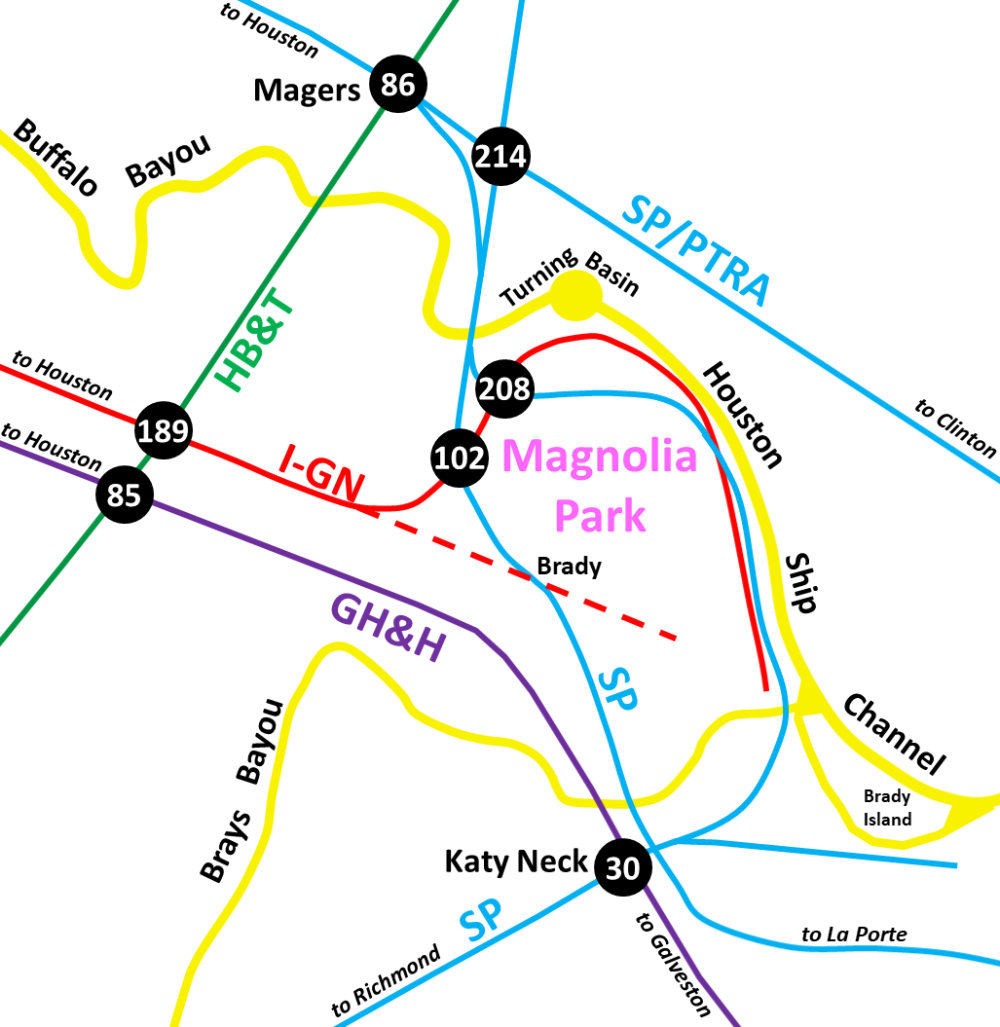

Below: notional overview

of historic rail lines showing seven interlockers within a 1.5 mile radius of Tower 102.

SP's tracks along the Ship Channel waterfront were

extended by PTRA to connect to the SP bridge over Buffalo Bayou to facilitate

easy access to PTRA's large yard on the north side of via

Galena Junction (Tower 214). This required crossing HB&T's former I-GN line

at a junction that was known initially as "Crossing C" near Old City Yard and

Booth Siding. Years later, a decision was made to interlock Crossing C to

improve traffic flow in the vicinity. On November 12, 1957, a letter from HB&T to RCT announced that

an interlocker at Crossing C had become operational on September 24, and

that this junction was "not previously interlocked but now controlled by Tower

30". The letter also requested RCT to "please assign tower number to interlocked

HB&T (I-GN) - PTRA crossing". The next day, a response letter from RCT

stated that the engineering department "can't find a file for this interlocker,

but will set one up", requesting additional details as to the precise nature of

the interlocking. This was provided in a return letter on November 15, and on

November 18, the Tower 208 designation for Crossing C was officially

conveyed to HB&T in a letter from RCT.

Below:

This image is taken from a map that appeared in the May, 1928 edition of

Port Book, a periodical produced by the Port of

Houston. The map is oriented with North to the left, and the Turning Basin at

the bottom. It is significant because it shows that by this date, there were two

bridges over Buffalo Bayou adjacent to the Turning Basin. The GL&H bridge is the

lower of the two in the image, attributed to the GH&SA. The other bridge is

immediately to the east (up) and is attributed to the Public Belt Railroad.

Technically, the Public Belt Railroad was the railroad operated by the PTRA.

South of the bridge (to the right), the track splits into two tracks, one of

which crosses the HB&T (ex-I-GN) Magnolia Branch at the future Tower 208. The

history of this bridge has not been determined and by 1939 it had

been removed, with the tracks to the port instead branching off of the GH&SA

tracks.

The GL&H bridge over Brays Bayou was dismantled by SP

between 1964 and 1966 according to historic aerial imagery. The tracks from

Harrisburg up to (but not including) the Buffalo Bayou bridge were taken out of

service and eventually removed. Instead, SP trains traveling between the north

side of Buffalo Bayou and points south of Brays Bayou were routed along the

south side of the Ship Channel, crossing Brays Bayou near its mouth on the

former Houston Municipal Railway bridge.

Above: This photo from c.1998

shows the Tower 208 crossing (magnification at right.)

Below: Two views looking north at the Tower 208

crossing: left (Kenneth Anthony photo, undated); right (Google Street

View, Dec. 2019), with sign providing radio communications instructions

Above: Facing north c.2006, the site of the Tower 102 crossing

is at the south end of a

greenbelt park and trail built along the former SP ROW. The HB&T Magnolia Branch

continues to Tower 208 to the right. The gate lock was still standing, padlocked

to prevent vandals from opening the phantom gate for ghost trains on the SP.

Below Left: This view looking

southwest along the HB&T at the Tower 102 crossing is a 3D perspective

transformation of a Google Earth satellite image. The SP ROW runs diagonally

from upper left to lower right. The large width of the ROW from left of center

to upper left is due to the HB&T connecting track that curved along the east

(left) side of the image. Traces of the connecting track can be seen in the

pavement at lower left a few yards to the left of the grade crossing. The switch

would have been approximately where the track intersects the lower edge of the

image. Below Right: Rails are

still evident in this December, 2019 Google Street View looking south from 75th

St. where the SP tracks crossed it approximately 100 ft. south of the

intersection of 75th St. and Avenue B, i.e. this is approximately the presumed

location of "Brady" and "Brady Junction". The switch was located somewhere in

this open field. The visible rails could either be the main track continuing to

Tower 102 or the connecting track to join the HB&MP rails heading into Houston.

The large utility tower above the red sign sits on the SP ROW and its power

lines proceed southeast (to the right, away from the viewer) to cross Brays

Bayou at the former GL&H bridge site.

Above Left: The Community Family Center on Ave. E was

built atop the former SP right-of-way, as evidenced by the rails buried in the

street. (Abel Garcia photo) Above Right:

a Nov. 2020 drone-captured image of the Buffalo Bayou bridge (Abel Garcia image)

Below: This drone image of the

Tower 102 crossing was captured in Nov. 2020 by Abel Garcia. The existing HB&T

Magnolia Branch remains active through the former crossing. The annotations show

the SP ROW (blue dashed line) and the spur track ROW (green dashed line.) The

Buffalo Bayou bridge in the above right photo is located where the dashed blue

line ends near the top right corner of the image. The tracks coming off the

bridge toward the camera swing to the southeast and cross the HB&T tracks at

Tower 208 off the upper right edge of the image.