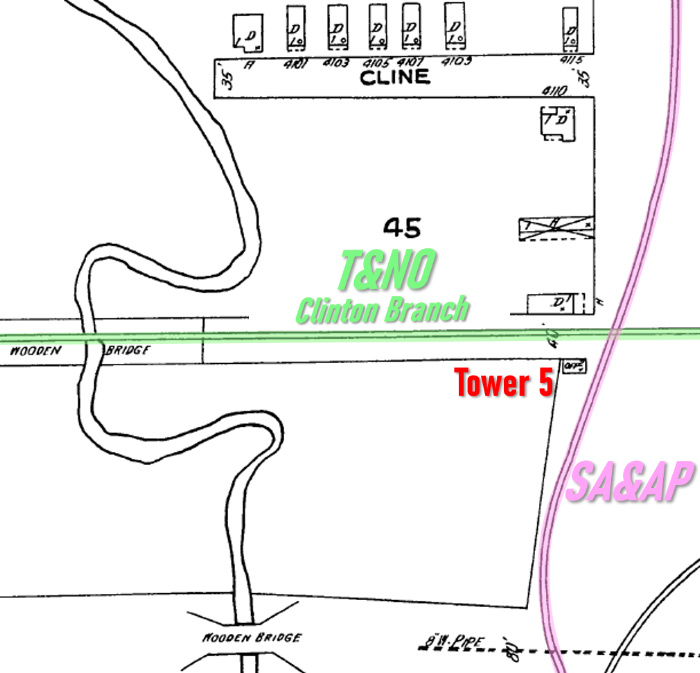

A Crossing of the Texas and New Orleans Railroad and the San Antonio & Aransas Pass Railway

|

Left: This crumbling concrete foundation was

found where Tower 5 is known to have stood in Houston. Whether this was

the foundation for the tower, or for the cabin interlocker that replaced

it, (or both!) is unknown. It appears too small for a manned tower, but

what's visible may not reflect all of the original foundation. The 1924

Sanborn Fire Insurance map of Houston shows the tower as a small,

2-story structure with no external staircase, but stairs were often

omitted from Sanborn maps. (Jim King photo, 2006)

Below: This 1947 image

((c)historicaerials.com) shows Tower 5 casting a northward shadow from

the southwest quadrant of the diamond where the north /

south San Antonio & Aransas Pass crossed the east / west Texas & New

Orleans. Out of service since 1941, Tower 5 had been converted to a

cabin interlocker in 1927. The lengthy shadow suggests a structure

taller than a typical interlocker cabin, so perhaps the original tower

building remained in place to serve as the cabin. The shadow remains

visible in 1966 imagery but does not appear in 1973 imagery. |

John Thomas Brady (sometimes incorrectly referenced as

Thomas M. Brady) was 26 years old when he arrived in Houston in 1856. Born in

Maryland, educated as an attorney, Brady settled at

Harrisburg near Buffalo Bayou and opened a law practice. Seeing Buffalo

Bayou on a regular basis no doubt influenced his thinking that it might one day

become a transportation artery for ocean-going vessels. To capitalize on his

vision, Brady bought 2,000 acres of land in 1866 along the south bank of Buffalo

Bayou, several miles east of downtown Houston. To develop

the property and build a rail line to serve it, Brady and other investors

established two companies, the New Houston City Company and the Texas

Transportation Company (TTC), which obtained a railroad charter from the Texas

Legislature.

Brady's timing was poor; the slow economic recovery after

the Civil War left investors leery of funding such ventures. Little construction

was ever accomplished, and by 1876, Charles Morgan had bought controlling

interest in the TTC. Morgan owned a large steamship business that dominated

shipping in the Gulf of Mexico. He wanted the TTC for its state charter because

it could be modified easily and he was in a hurry. Instead of the south bank of

Buffalo Bayou,

Morgan's TTC line would run along the north bank from near

downtown Houston to Morgan's newly established port of Clinton, a distance of eight

miles. Morgan had already paid to dredge a channel to the Gulf deep enough for

his ocean-going steamships, so he wanted rail service to Clinton as quickly as possible

to gain a return on his investment from shippers willing to use his port. (The

first use of the Clinton port was to bring in materials for the rail line's

construction.)

Shortly after the TTC line was completed, Morgan

established Morgan's Louisiana and Texas Railroad and Steamship Company for his

various steamship operations and the

TTC. In 1877, he increased his shipping empire by purchasing the Houston & Texas

Central (H&TC) Railway. The H&TC had completed a line between Houston and

Denison where it connected to the Missouri, Kansas & Texas (MK&T) Railway

that had built south from Kansas through Indian Territory and bridged the Red

River to enter Texas. Morgan could route Midwest

export commodities from the Red River to Houston and funnel them to Clinton via

the TTC as an alternative to Galveston, the

dominant Gulf port in Texas. Morgan died in 1878 and his holding company was subsequently acquired by

SP, which assigned the TTC rail line to one of its Houston-area

subsidiaries, the Galveston, Harrisburg & San Antonio (GH&SA) Railway,

though it remained a separate legal entity. In 1896, the Texas Legislature

authorized the TTC to be acquired and merged into SP's Texas & New Orleans

(T&NO) Railroad subsidiary. By then, the tracks had become widely known as the Clinton Branch.

|

The San Antonio & Aransas Pass (SA&AP) Railway entered Houston in 1888 from

the west, crossing south of downtown and opening a depot at Polk Street.

The SA&AP's main line was between San Antonio and

Corpus Christi, but the railroad had begun building

two lengthy branch lines: the one to Houston and

another to Waco.

To access T&NO's Englewood Yard on the

northeast side of Houston, SA&AP built an extension from Polk St. that

bridged Buffalo Bayou. Less than a half mile beyond the north bank, the

SA&AP crossed T&NO's Clinton Branch. On December 4, 1902, the Railroad

Commission of Texas (RCT) authorized Tower 5 to commence operation at

this crossing with a mechanical interlocking plant with twelve

functions: a home signal, distant signal and derail in each direction.

This was the minimum function set for a basic crossing with no control over interchange tracks (if any

existed at the outset.) Initially, RCT listed Tower 5 as being

in "East Houston" but this was subsequently changed to "East of Houston", a

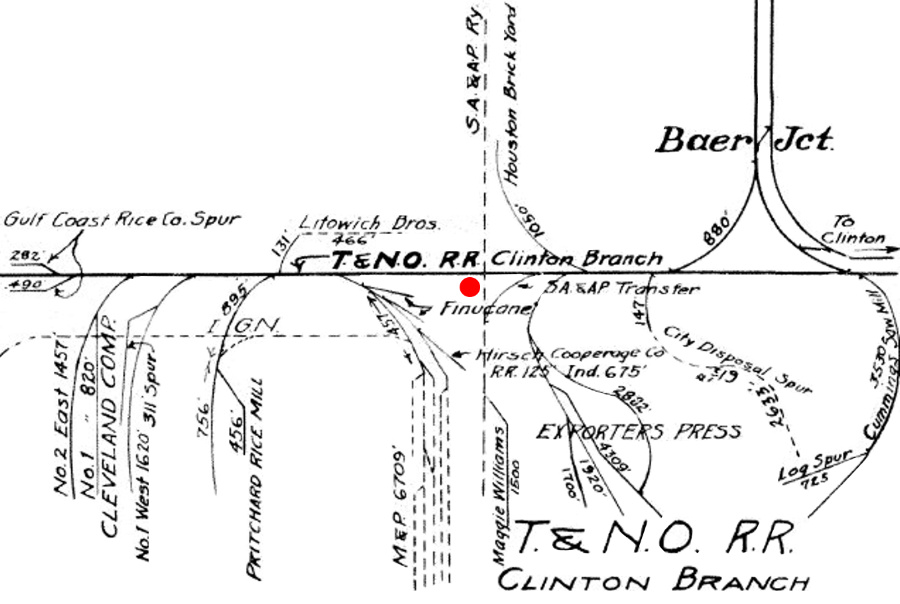

location that persisted through RCT's final interlocker list published in 1930. Left: This 1926 T&NO track chart (Carl Codney collection) shows the complexity of industrial spur tracks in the vicinity of Tower 5 (red dot annotation.) Baer Jct. nearby was a T&NO route to Englewood Yard controlled by Tower 86. Numerous industries had located along Buffalo Bayou, which was navigable by smaller steamboats and barges. Farther east, the bayou had been dredged to form the Houston Ship Channel which opened in 1914, but ocean ships did not proceed west of the Turning Basin, about three miles downstream from the vicinity of Tower 5. |

|

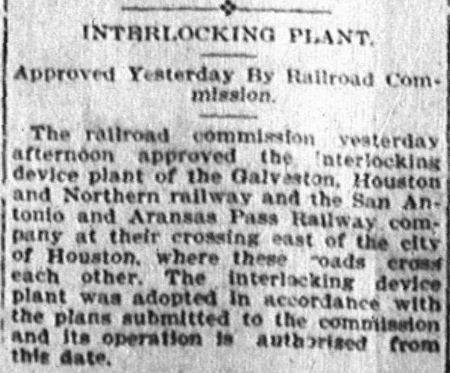

Right: The

Austin Daily Statesman of December 5, 1902 carried this news

item reporting RCT's approval of the Tower 5 interlocker. The east / west line crossed by the SA&AP

is reported to have belonged to the Galveston,

Houston & Northern (GH&N) but this is problematic given T&NO's

ownership of the TTC. The GH&N had been chartered in March, 1899 to acquire the bankrupt Galveston, La Porte and Houston (GL&H) Railway. The GL&H had been an attempt to link several small railroad properties into a continuous route between Houston and Galveston, crossing over to the island on a new bridge. The GL&H's long term plan was to assemble a railroad that would be attractive to SP, taking advantage of an odd situation -- the largest railroad system in Texas (SP) did not have a bridge to the largest port in Texas (Galveston). To further entice SP, the GL&H built a bridge over Buffalo Bayou at Constitution Bend (now the Turning Basin.) This allowed the GL&H to provide a direct Galveston route for industries served by SP on the north bank. It also gave the GL&H a direct route to SP's passenger depot via the Clinton Branch. In early 1896, before the new Galveston bridge was finished, the GL&H filed for bankruptcy protection on January 7, having exhausted its capital in less than a year. The sale of the GL&H to the GH&N was completed in April, 1899 and the GH&N began operating the GL&H's routes and trackage rights with SP. The GH&N ownership group had been assembled by SP, and SP managers operated the GH&N even though it was an independent railroad. The GH&N officially became part of SP when a state law was passed in 1905 allowing SP to acquire it and assign its assets to one of its Texas railroads, the GH&SA. By 1902, GH&N trains using T&NO trackage rights may have been the primary user of the route past Tower 5, and this could explain the news item's citation to the GH&N being involved with the interlocker. The Clinton Branch, however, had been under T&NO ownership since 1896 and SP ownership since the mid 1880s. |

|

|

Left: This inset map is part of the above 1926

T&NO track chart, highlighting the SA&AP transfer track. It was 667

ft. in length and merged onto

the eastbound Clinton Branch in the southeast quadrant of the crossing

diamond. Tower 5 is the rectangle southwest of the diamond. Right: This 1924 Sanborn Fire Insurance map of Houston has been annotated to highlight the SA&AP crossing of the T&NO Clinton Branch at Tower 5. The Clinton Branch ran east / west; the SA&AP ran generally north / south, terminating at Englewood Yard about a mile north of Tower 5. The map depicts Tower 5 as a small rectangle in the southwest corner of the crossing. Magnification reveals the lettering inside the Tower 5 rectangle to be 'Off' [office], suggesting a regularly manned facility. The numeral '2' is also visible, indicating a two-story structure. A tiny mark below the '2' indicates a doorway on the south side of the building. The tower's size can only be conjectured from the map, but it appears smaller than expected. Although Sanborn maps sometimes illustrated external staircases for railroad towers (e.g. Towers 9 and 41), this one does not, but no implication can be drawn from that detail. Note that the track segment in the lower right corner is a snippet of the SA&AP transfer track shown on the map at left. |

|

SP documents obtained by Carl Codney paint a complex picture of Tower 5's existence. The tower timeline appears normal until November, 1918 when it was "temporarily" taken out of service for a 16-month period. This was due to the nationalization of the railroads under the U. S. Railroad Administration (USRA) on December 28, 1917 to optimize their use in support of World War I. Within a year, USRA had shut down unnecessary rail lines and expanded the use of others. Terminating operations on specific tracks made the collective railroads more efficient and eliminated unnecessary maintenance costs. An SA&AP employee timetable issued by USRA on October 12, 1919 specifically states "All trains use H&TC tracks between Bellaire Jct. and Englewood...". SP's tracks to Englewood provided a better route from Bellaire Junction (Tower 104), where SA&AP's branch line to Houston crossed two parallel north / south SP tracks, the H&TC and the GH&SA, which operated as a double-track for SP. Inbound SA&AP trains from the west would turn north at Bellaire Junction and proceed to Englewood via Towers 13 and 14 rather than continue east across the south side of downtown to Englewood via Tower 5. SA&AP passenger trains had already begun using SP's depot on the north side of Buffalo Bayou which was along the route to Englewood.

|

Right: SP used an internal form to provide a

high-level summary of each interlocking with which it was associated.

This form (Carl Codney collection) was used to document Tower 5. It is

dated, "Dec. 3rd, 1903", almost a year after Tower 5 was commissioned,

so it may represent an initial revision. Numerous other typed and

hand-drawn comments and other amendments reflect how it was updated over

the decades. Carl's collection includes a version of the Tower 5

document released for Plan D-1045 (plan dated September 23, 1926) for

the tower's conversion to a cabin interlocker, but the document is

undated. The Transportation Act of 1920 returned the railroads to private ownership, but it also granted substantial control over them to the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC). Congress directed the ICC to promote and plan consolidation of U.S. railroads into a limited number of "systems". The ICC responded by hiring economist William Z. Ripley to perform the study. The so-called "Ripley Plan" proposed that SP head one of these systems and that the SA&AP become part of it. Although the Ripley Plan was never formally implemented, the authority granted to the ICC to regulate interstate railroads overrode the power of state railroad commissions. On December 6, 1924, SP filed an application with the ICC for authorization to obtain control of the SA&AP. The State of Texas opposed the move, but was overruled by the ICC when it granted SP's application. In March, 1925, the SA&AP was acquired by SP and leased to the GH&SA. Extracting all of the dates from these documents as well as dates from RCT information obtained elsewhere produces this timeline for Tower 5:

The newer version of SP's document, filled out only in handwriting, was likely created when this one was "Rewritten 6/14 - 37". Since the cabin interlocker was placed in service March 10, 1927, it is possible that "37" should be "27". The newer document merely repeats the handwritten functions that appear on this document, with one additional notation: "Out of service Jan. 2 - 1941." |

|

After reinstatement from USRA control, there are no

other operational notes until Tower 5 was removed from service in 1925 when SP acquired the

SA&AP. Closing the tower was consistent with the original RCT policy that

required numbered interlockers only where two different railroads

crossed. Once the SA&AP had been brought formally under SP control, the

numbered interlocker was, in theory, no longer required or subject to RCT

management, even though the interlocking function might still be valuable. This

concept had changed over time, however, beginning with Tower 121

where, in April, 1925, SP requested approval for its yard tower in San Antonio

even though no other railroads were involved. It is likely that after the

removal of Tower 5 from service due to the SA&AP acquisition, SP evaluated local

operations and decided that a cabin interlocker was

appropriate. SP's interlocker plan dated September 23,

1926 was for the new cabin design, but whether it was submitted to RCT for approval

is undetermined. About

six months after Tower 5 was "replaced in service as cabin interlocker on March

10, 1927...", RCT's inquiry to the Panhandle & Santa Fe regarding

their interlocker at Canyon again raised the

specific issue of whether a single-railroad interlocker needed RCT approval.

From that point forward, RCT's interpretation of its authority was that

all interlockers required RCT approval.

It is interesting that the document says "Replaced in service

as cabin interlocker" (emphasis

added) which can be construed as indicating the existing tower was being reused.

If the cabin interlocker was a new structure, it seems more likely that "by"

would have been used. This could support the idea that the lengthy shadow in the

1947 imagery resulted from the cabin interlocker being implemented using the

original Tower 5. Cabin interlockers were used for simple crossings where the

traffic was insufficient to justify a manned tower, typically in cases where one

line was much busier than the other. The interlocker normally would be lined

to permit continuous movement on the busier track. Trains approaching on the lightly used line

always stopped at the diamond so that a crewmember could enter the cabin to set

the trackside signals granting his train passage

over the crossing. After the train had completed its crossing, the crewmember would re-line

the signals to allow trains on the busier line to resume unrestricted operation.

The T&NO Clinton Branch was the busier line at Tower 5, and that explains why

"T&NO RR" is crossed out in the "OPERATED BY" field and replaced by a

handwritten "SA&AP Ry." The original Tower 5 was operated by T&NO employees, but

the cabin interlocker was operated by train crews from the lightly used line --

the SA&AP.

SP's acquisition of the SA&AP resulted in a resumption of the traffic

pattern that USRA had previously imposed. Trains on

the SA&AP line west of Houston returned to accessing Englewood Yard via

Bellaire Junction and Towers 13 and 14. This reduced traffic past Tower 5, and

that motivated downgrading it from a manned tower to a cabin

interlocker. RCT files mention that Tower 5's cabin interlocking controls were

relocated to

Tower 139 beginning in 1940, suggesting that a remote

control capability was engineered. It apparently didn't last long; SP's document says that the Tower 5 interlocker was

"out of

service" on January 2, 1941, somewhat less than a year after remote

control was installed at Tower 139.

Above Left: Tracks to the Tower 5 site remain in place

from the east. The grade crossing signals are for Hirsch Rd. Above Right: The

tracks from the east curve to the north and then make an S-curve slightly

to the east to connect to the original SA&AP northbound track alignment.

Below Left: To the west, the

T&NO Clinton Branch toward Tower 139 is abandoned.

Below Right: The view to the south

from the Tower 5 site shows this odd-looking greenbelt occupying the former SA&AP right-of-way toward Buffalo

Bayou south of Clinton Drive. (Jim King photos, December 2006)

Above:

This simulated Google Maps 3-D view looks south toward Buffalo Bayou. The only surviving track at

the Tower 5 crossing is the former northeast quadrant connector. The switches

have been removed and the former connecting track is now a continuous line from

the remnants of the Clinton Branch east of Tower 5 into Englewood Yard.

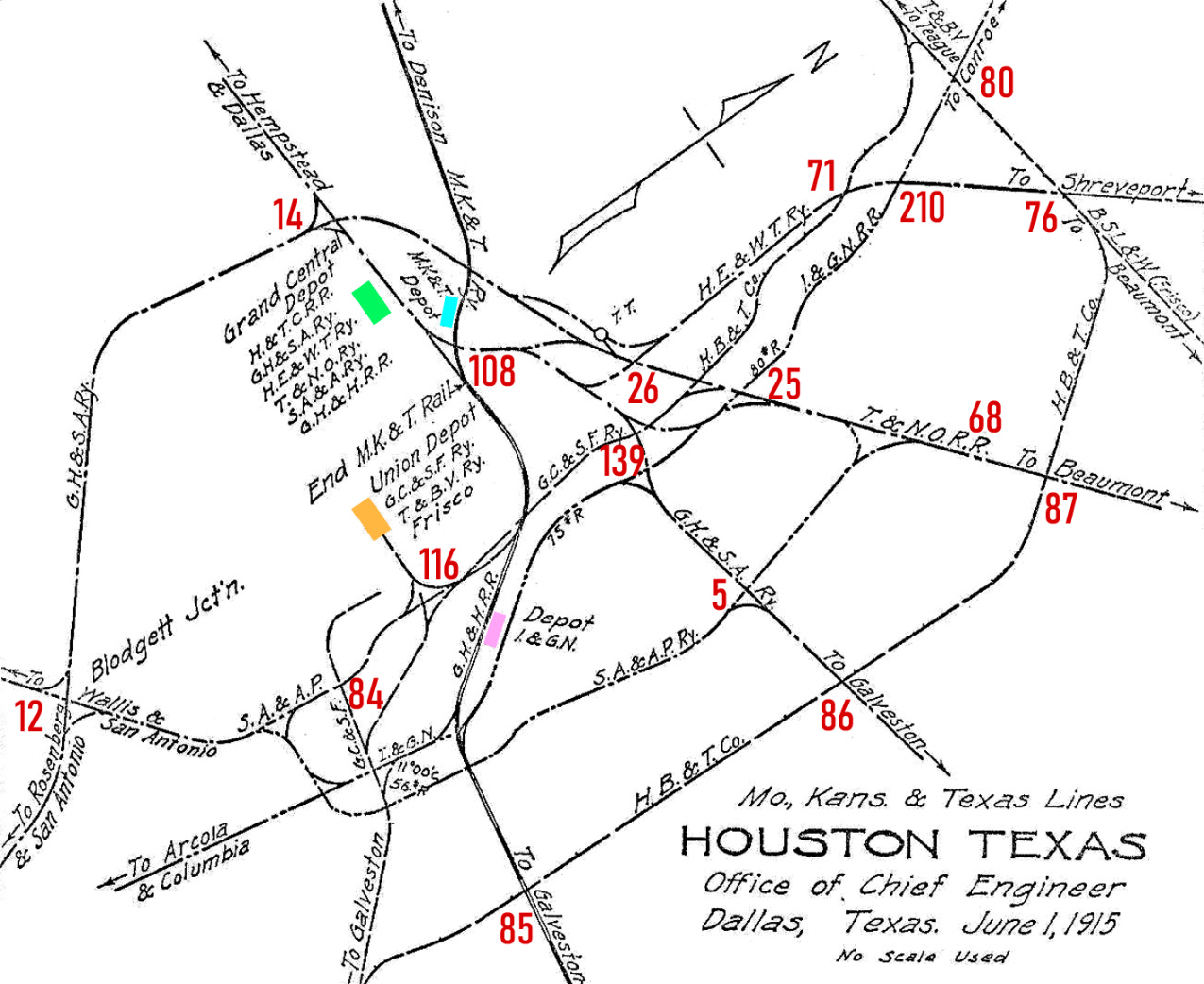

Below: This track chart of

Houston created in 1915 by the Missouri, Kansas & Texas (MK&T) Railway has been

annotated to identify interlocked crossings by tower numbers (which do not

necessarily show a tower's position relative to its diamond.) Note that Towers

108, 139 and

210 had not been built as of 1915. Tower

116 was operational but had not

been formally commissioned by RCT. There are a few towers that are not shown

because they are just off the map, e.g Towers 13

and 117, or the crossing protected is not on the

map, e.g. Tower 102. All of the towers can be found

here. Four passenger depots are highlighted. The

chart shows that SA&AP passenger operations had already moved to SP's Grand Central Depot

(green rectangle.)

|

Left:

This recent satellite image from Google Maps shows that not much is left of the

tracks at Tower 5. The former Clinton Branch from the east now curves

north onto the former SA&AP route and remains in service into Englewood

Yard. Everything else is gone. Historic imagery shows that SP kept a portion of the former SA&AP tracks intact in the vicinity of Tower 5, at least to the mid 1990s when Union Pacific acquired and merged with SP. The former SA&AP bridge over Buffalo Bayou is visible in 1995 imagery but is gone by 2002. In the 1995 imagery, the only route for trains going north over the bridge was to curve to the east at Tower 5 on a connecting track in the southeast quadrant. The "straight through" SA&AP track to Englewood Yard and all of the former Clinton Branch to the west had been removed. |