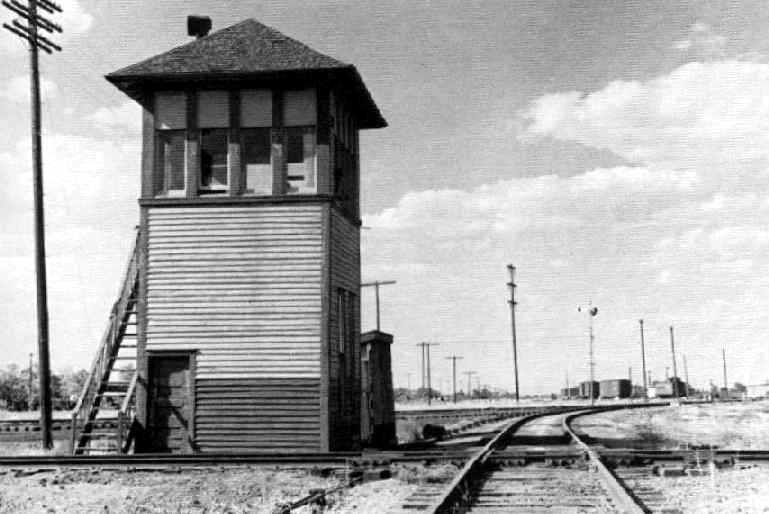

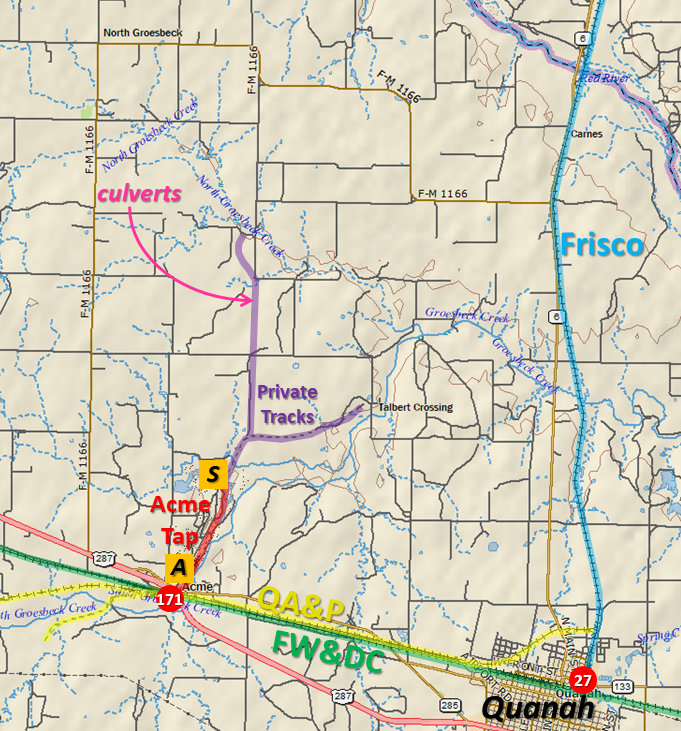

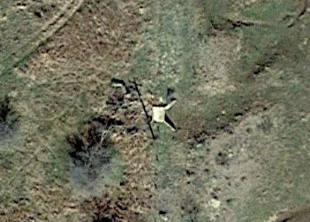

Above: Tower 27, as pictured in The Quanah Route, by Don L. Hofsommer (1991, Texas A&M University Press)

The Story of the Quanah, Acme &

Pacific Railway

Above: Tower 27, as pictured in

The Quanah Route, by Don L. Hofsommer

(1991, Texas A&M University Press)

When the Ft. Worth & Denver City (FW&DC) Railway built

north out of Ft. Worth in the early 1880s, its

objective was to complete a line to the New Mexico border in the upper Texas

Panhandle, part of a lengthy route between its namesake towns. ("City" was

officially dropped from the FW&DC's name on August 7, 1951, hence both "FW&DC" and

"FW&D" are used as acronyms.) Tracks reached Wichita Falls in 1882 and the route

continued west, paralleling the Red River several miles to the south. Survey

teams had identified future water stops and towns, one of which was named Quanah

for the famous Comanche Chief, Quanah Parker. Lots were being sold in Quanah by

1885 and a Post Office opened in 1886, even though the railroad didn't arrive

until the following year. By 1890, the town's prosperity was sufficient to win

an election to become the seat of Hardeman County. Deposits of natural cement

and gypsum were discovered near Quanah, leading to the development of a local

industry with two plants manufacturing cement and gypsum products. In 1898, a post office opened at the

community of Acme

where the cement and plaster industry was centered, 6 miles west of Quanah along the FW&DC

main line.

One of the two plants, the Acme Cement Plaster Co. owned by

Samuel Lazarus, was directly adjacent to the rail line at Acme and arranged for

the FW&DC to perform switching duties. The other plant, the Salina Cement

Plaster Co., was north of Acme. It also needed rail service but could not reach

the FW&DC tracks without crossing Lazarus' property. Lazarus refused to grant an

easement, so a new railroad, the Acme Tap, was chartered in 1899 by the Salina

plant's owners. The state charter enabled the Acme Tap to condemn an easement across

Lazarus' property so it could build the mile and a half of track needed to reach

the main line. The FW&DC performed the rail construction for the Acme Tap

and also supplied the equipment needed to operate it and switch the Salina plant.

Additional private tracks were built north of the Salina plant to reach gypsum

deposits.

Above Left: FW&D #201 at Acme,

photo undated (Billy Brackenridge collection)

Above Right: undated photo of the

FW&D railroad station at Acme (Kerry Kennington family collection)

Business was good, but Samuel Lazarus was unhappy with the freight

rates being offered by the FW&DC. His solution was to build his own railroad to reach

another connection that could provide suitable competition. For this purpose, his Acme, Red River

& Northern (ARR&N) Railroad was chartered in 1902 with a vague plan to build to

the Red River, bridge it, and continue to Mangum, Oklahoma to connect with the Rock Island

railroad.

But bridging the river was beyond Lazarus' budget, so he looked for another

opportunity. At the time, the St. Louis - San Francisco (SL-SF, "Frisco")

Railway had begun building southwest out of Oklahoma City toward the Red River

with plans to enter Texas. Lazarus proposed to the Frisco that they alter their

planned route and meet his new railroad at the Red River north of Quanah. An

agreement was reached, but it was soon modified to have the ARR&N build directly to

Quanah instead.

Texas law mandated that all railroads

owning tracks in Texas be headquartered in Texas. In the initial plan,

the ARR&N would have fulfilled that requirement for the Frisco by meeting them at the Red

River. Under the revised plan, the Frisco needed to charter a railroad, the Oklahoma City & Texas (OC&T) Railroad, to

own the nine miles from the river to Quanah. This was not unusual for the Frisco;

they had chartered Texas subsidiaries in the past merely to comply with the law,

e.g. the

St. Louis, San Francisco & Texas Railway (SLSF&T) at

Denison,

the

Paris & Great Northern Railroad at Paris, and

the Red River, Texas & Southern Railroad from Sherman

to Carrollton. The

OC&T line to Quanah was completed in 1903, and the following year, the

Frisco merged most of its Texas subsidiaries, including the OC&T, into the

SLSF&T. Although the SLSF&T continued operating as a wholly-owned subsidiary

until 1962, most (or perhaps all) of its rolling stock belonged to its parent

company. It was, in essence, a holding company for Frisco's operations in Texas.

| The OC&T's tracks into Quanah made a connection on the north side of town with

the FW&DC. They also crossed over it and continued down the center of McClelland

St. to 10th St., nearly three quarters of a mile farther south. This enabled the Frisco to

serve businesses in town and also provided a location for a passenger station

between 3rd and

4th streets. On October 5, 1903, the Railroad

Commission of Texas (RCT) gave approval for commencement of operations of the manned interlocking

tower that had been built at the crossing of the OC&T and

the FW&DC. Designated Tower 27, the interlocker was a 19-function mechanical plant

built by the Pneumatic Signal Co. of Rochester, New York. Since the OC&T was the

"second railroad", i.e. the one that created the crossing, they were responsible

for the capital outlay to build the interlocking tower. (Had the crossing

existed when Texas' new interlocker law took effect in 1901, the capital expense

would have been shared by both railroads.) By the end of 1904, RCT documentation had

been updated to show the SLSF&T replacing the OC&T as a participating railroad at Tower 27. RCT statistics show that during

the 12 months ending June 30, 1906, an average of 17 train movements per day

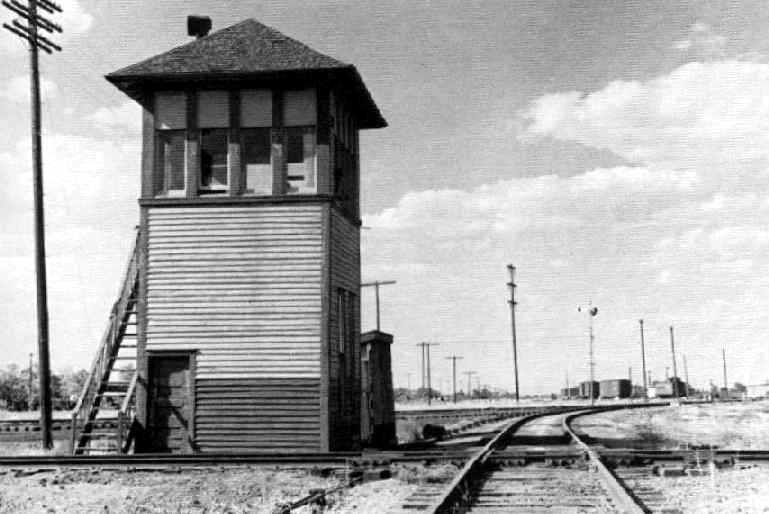

passed Tower 27. Right: Austin Daily Statesman, November 8, 1902 Even if the Frisco was responsible for paying to design and erect Tower 27, it's still possible that the FW&DC actually performed the engineering work and built the structure. That is, whether this was a "Frisco tower" or an "FW&DC tower" has not been conclusively established with respect to its design and construction. From an operational standpoint, it was a Frisco tower. |

|

RCT's Annual Report of

1917 was the first to list the railroads at each tower in a particular order

such that "First Railroad named Operates the Interlocker". It listed the SLSF&T

first, indicating it was the railroad responsible for operating Tower 27 (it

also showed the function count had increased to 34; most likely, exchange track signaling

and switching was becoming more extensive.) In almost every case where the

details are known, the railroad with the responsibility for operating the

interlocker was also the railroad that designed and built the tower, regardless

of which railroad (or perhaps both) had funded it. The reason

for this was simple: railroads liked to be able to relocate and "fill in"

personnel among multiple towers as needs and vacancies arose, and as traffic and

operational hours changed (many towers were not staffed 24/7, and hours were

often discontinuous on Sundays.) With each railroad mostly staffing only the

towers it had built, its operations benefitted from having commonality in its

tower designs. While the capital costs for Tower 27 would have been borne by the

Frisco, annual recurring costs for operations and maintenance would have been

shared, typically on a "weighted function" basis subject to negotiation between

the railroads involved, here, the Frisco and the FW&DC.

The OC&T was supposed to connect with the ARR&N at

Quanah, but the ARR&N was nowhere to be found! Before

Lazarus could build the ARR&N line into Quanah, the FW&DC made a proposal. They

would grant rights to the ARR&N to handle the switching duties at both plaster

companies, and also grant rights for the ARR&N to use the FW&DC main line

into

Quanah.

For its part, the ARR&N would agree not to build its own line into Quanah.

Lazarus accepted the FW&DC's offer; the ARR&N began switching both plaster plants which included

a 10-year lease on the Acme Tap. The ARR&N regularly used the FW&DC main line to move freight cars to and from

Tower 27 to exchange with the Frisco. Exchanges with the FW&DC could be done at

Acme.

In 1909, the ARR&N was re-chartered

as the Quanah, Acme & Pacific (QA&P) Railway which immediately announced plans to expand

west from Acme with the intention of planting new ranching towns in the sparsely

populated region. The QA&P's ultimate (though unlikely) goal to reach El Paso

was included in the new charter. The QA&P purchased a right-of-way

200 ft. wide on the south side of the FW&DC from Acme to Quanah to reach new passenger and

freight stations they planned to build a block south of the FW&DC near

downtown. Once again, to deter the QA&P,

the FW&DC proposed to amend the existing switching and trackage rights

agreement. They would build a spur off their main line to serve the QA&P's

planned passenger and freight stations. In exchange, the QA&P would agree not to

build their own line into Quanah. The offer was accepted, and the stations and

the spur were built. At some point, the Frisco abandoned its

passenger station and began sharing the new QA&P station, but the date when

that occurred has not been established.

|

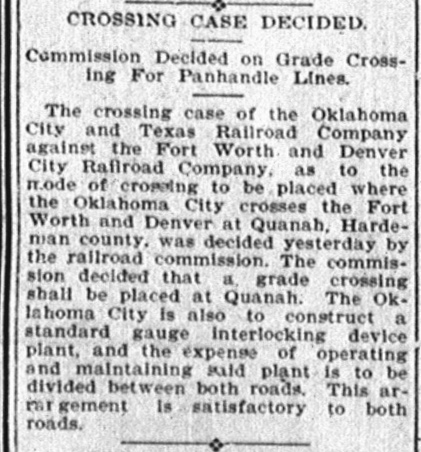

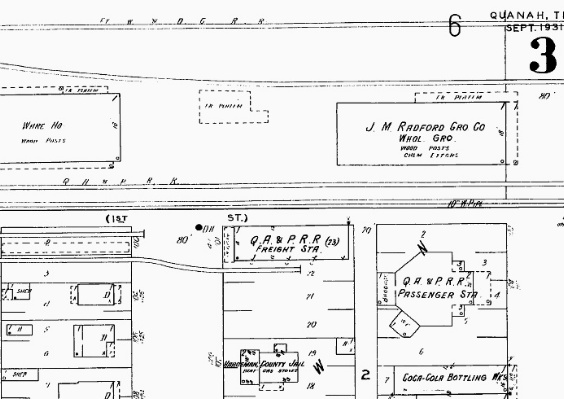

Left:

This 1931 index map from the Sanborn Fire Insurance Co. has been

annotated to show the Frisco tracks (yellow highlight) coming into

Quanah from the north, continuing south down McClelland St., and ending

at Tenth St. The Frisco's passenger station (blue rectangle) sat along

McClelland between Third St. and Fourth St. (although by this date, it

was likely abandoned in favor of using the QA&P depot.) The FW&DC tracks (pink highlight) run east/west through Quanah, with Tower 27 located at the FW&DC / Frisco crossing (red circle). Assuming the photo of Tower 27 above looks due north with the QA&P/Frisco yard in the background (and with the track slightly curving to the east as depicted on the map), it appears that Tower 27 was located in the northwest quadrant of the diamond. The QA&P depot (green rectangle) and FW&DC depot (orange rectangle) were west of Tower 27, due north of the courthouse square. Because this map dates from 1931, after the QA&P lost trackage rights on the FW&DC, the (un-highlighted) track on the north side of the QA&P depot extends east and connects to the Frisco tracks going north at Tower 27. This connection was added because the spur track off the FW&DC (farther west) that had provided depot access was no longer available due to the termination of the trackage rights agreement. By the 1931 date of this map, the Frisco tracks had been leased to the QA&P for many years (since 1914), a situation that appears to have remained in effect until the demise of the QA&P. |

|

Above Left: This view of the QA&P passenger depot was

taken in June, 2008 during the excursion to Quanah that was part of the Lone

Star Rails 2008 convention of the National Railway Historical Society (NRHS). The depot

houses the Hardeman County Historical Museum. (Jim King photo)

Above Right: The 1931 Sanborn

Fire Insurance map of Quanah shows that the QA&P had a freight station

adjacent to

their passenger depot. The Coca-Cola Bottling Works and the county jail were also

nearby. The jail has survived as a historical structure.

With the arrangements in Quanah settled, the QA&P

focused on their plan to expand west. As they already had FW&DC trackage rights

from Quanah, the QA&P's route west began with a switch off the main

track at Acme. They proceeded southwest to Paducah, an

existing town reached easily in 1910. The terrain farther west presented

much more difficult construction due to the looming Caprock Escarpment. To raise capital for the venture, a series of

complicated financial arrangements appeared to leave the Frisco owning a controlling

interest in the QA&P. An agreement was reached wherein the Frisco guaranteed the

construction bonds of the QA&P but this did not settle the ownership

question. The financial

arrangements were complex due in part to the Frisco's reorganization in

bankruptcy between 1913 and 1916. As late as 1922, the QA&P was still notifying

the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) that "...records

of this company reflect no such control nor does SL&SF Railroad Company exercise

control." This statement was in a letter sent each year in response to the

ICC's annual report listing the QA&P's capital stock as entirely owned by the

Frisco. When all the financial dust settled, the QA&P was indeed owned by

the Frisco, but continued to operate independently.

With funding

in place, construction west from Paducah began in 1913 and proceeded toward the

vast ranchland of the Matador Land and Cattle Co. which had granted a

right-of-way. Along the way, a camp eight miles south of the town of Matador

(where the ranch was headquartered)

became the new town of Roaring Springs. Construction

continued another four miles west ending at MacBain, forty

miles from Paducah. MacBain was named for the head of the Matador company,

John MacBain, who anticipated the site becoming a livestock loading point.

The QA&P would not build beyond MacBain for more than a dozen years,

and during this period, operations along the entire line west of Quanah were sustained in part by

shipping cattle. The QA&P tracks were a boon to ranchers who could

conveniently move

cattle to markets in Ft. Worth and Oklahoma City. Transporting cattle by

rail required compliance with laws regarding watering, feeding and rest, and cattle

pens to support such stops also had to be built. Railroads were repeatedly

subject to claims by ranchers whenever cattle died en route. It was a difficult

but worthwhile business, and it helped to maintain cash flow for many years.

|

Left: Current maps show MacBain at latitude 33 53 37 N, longitude 100 58 29 W, about four miles farther west than it was when the QA&P was being built. The cattle shipping point was relocated in later years, and the stock pens built there remain intact adjacent to the abandoned QA&P grade. (Google Earth, 2016) |

World War I came and went, disrupting railroads with the creation of the U. S.

Railroad Administration. In the post-war era of the early 1920s, Texas railroads

had begun to examine the

landscape for new opportunities, one of which was the area of farm

production on the South Plains of Texas near Plainview and Lubbock, above the Caprock Escarpment. The QA&P and

the FW&DC saw viable business prospects in the area which was already

served to some extent by Santa Fe. Various plans were submitted to the ICC, and

after much delay and vigorous opposition by Santa Fe, some were approved. One of

the projects recommended by the ICC was the QA&P's proposal to build west from MacBain to

Floydada, a town chosen because it was nearby and had an existing rail line to Plainview. Floydada had become a

railroad town in 1910 when its citizens organized a company called the Llano

Estacado Railway to build a branch to Floydada from an existing rail line at Plainview. As grading operations

commenced that year, the Pecos & Northern Texas (P&NT) Railway acquired the assets and

completed the 27 miles to Floydada. The P&NT was a subsidiary of Santa Fe, and

the line to Floydada became one of several Santa Fe branches in the South Plains.

From MacBain, the QA&P had preferred to build to either Lubbock or

Plainview, but competition from the FW&DC and Santa Fe was coming quickly on the South

Plains. The QA&P did

not want to be stuck forever with a dead-end at MacBain while there was a good likelihood of approval to build to

Floydada. It was only 27 miles away on the plains atop the Caprock

Escarpment, but to get onto those plains, eight rugged miles of construction

remained. There were unexpected

financial delays that irked the citizens of Floydada who had promised

right-of-way and land for a depot, expecting the rails to arrive sooner

than they did. The QA&P's construction finally commenced west from

MacBain on June 15, 1927 and the rails reached Floydada in April, 1928.

While the locals were thrilled to have a new rail line providing faster service to Ft. Worth, St. Louis and

points east, Santa

Fe did not want its branch line at Floydada to connect with the QA&P. In particular, they did not want to exchange Frisco traffic over

this branch line because Santa Fe and the Frisco already had a

better connection at Avard, Oklahoma. But after limited negotiations, the rail connection

was made, and soon, a small flow of connecting traffic began to materialize

through Floydada.

Above:

The Matador Land & Cattle Co. had

offered to share land sales at Roaring Springs with the QA&P, knowing

that a route through

Matador, the seat of Motley County, would have provided no opportunity for townsite

development. Matador residents were miffed, believing that the

presence of the railroad would result in Roaring Springs becoming the county seat,

leaving Matador to wither. To counter this, in 1914 they organized and built the Motley

County Railway, an 8-mile track to a QA&P junction three miles east of

Roaring Springs. Whether or

not their strategy was actually vindicated, Matador remains the county seat

and is still larger than Roaring Springs. The line became a QA&P branch in 1926 and

was abandoned in 1936. Above:

The Matador Land & Cattle Co. had

offered to share land sales at Roaring Springs with the QA&P, knowing

that a route through

Matador, the seat of Motley County, would have provided no opportunity for townsite

development. Matador residents were miffed, believing that the

presence of the railroad would result in Roaring Springs becoming the county seat,

leaving Matador to wither. To counter this, in 1914 they organized and built the Motley

County Railway, an 8-mile track to a QA&P junction three miles east of

Roaring Springs. Whether or

not their strategy was actually vindicated, Matador remains the county seat

and is still larger than Roaring Springs. The line became a QA&P branch in 1926 and

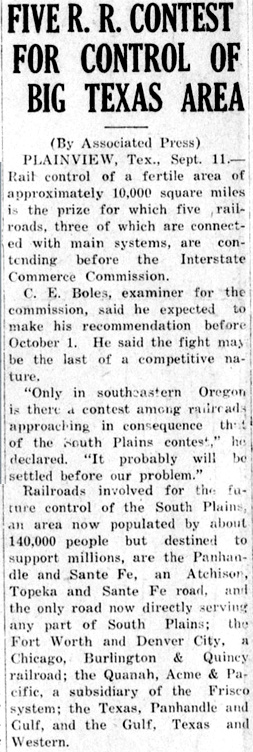

was abandoned in 1936.In the mid-1920s, the FW&DC began an aggressive push to gain ICC approval of proposed routes onto the South Plains. In 1927, the FW&DC started construction on a branch from their main line at Estelline, 44 miles northwest of Quanah, and ventured west into the Caprock. It required two tunnels to get atop the escarpment to reach Plainview in 1928, continuing to Dimmitt that same year. They also built a new line between Silverton and Lubbock that crossed the Santa Fe at Lockney. Where the two new FW&DC lines crossed, the tiny community of Sterley arose. Trains from the FW&DC at Estelline could proceed west to Sterley and turn south, creating a rail route between Ft. Worth and Lubbock. Meanwhile, Santa Fe already had a major secondary line between Lubbock and Canyon via Plainview, with branches to Floydada and Crosbyton, plus additional lines out of Lubbock. They viewed the South Plains as their territory, and they were not happy to see other railroads invading it. Right: This Associated Press article dated September 11, 1925 appeared in the Calexico Chronicle (California) newspaper describing the competition underway among railroads wanting to serve the South Plains of Texas. Of the final two railroads mentioned in the article, only the Gulf, Texas & Western actually existed. By 1910, it had managed to lay 75 miles of track from Jacksboro to Seymour heading generally toward the Caprock, but it never continued onward to the South Plains. After stints as both a Frisco and a Rock Island property, the line was abandoned in 1942. The Texas, Panhandle & Gulf was a company that proposed to build a rail line from Ft. Worth to Tucumcari, New Mexico. When the ICC approved their application in March, 1926, they were given six months to acquire the necessary capital to begin construction. They failed to do so and their application was dismissed by the ICC in September. |

|

Above Left:

abandoned QA&P right-of-way viewed northeast from US 70 west of Paducah

Above Right: abandoned QA&P

right-of-way nearing the top of the Caprock, viewed northwest from Farm Road 684

Below Left: Paducah

Heritage Museum in the old QA&P depot

Below Right: QA&P depot in Roaring Springs. (Google

Street Views, 2013)

Toward the end of 1913, the QA&P's lease of the Acme Tap

was about to expire. The plant that owned the Acme Tap was no longer the Salina

company; ownership had passed to the American Cement Plaster Co. As the QA&P

sought to renew the Acme Tap lease, they also proposed to change the waybill

location for shipments originating on the Acme Tap as a means of differentiating

the two plants. The QA&P proposed "Clay-Bank" as the official location of

American's shipments, which American rejected. American was less well known;

having products identified as originating at Acme, a recognized source of such

goods, was considered beneficial to their brand. Either Acme Plaster or the QA&P complained

to RCT about continuing to identify Acme as the home of the American plant when

it was located more than a mile away. With RCT involvement, the

parties ultimately agreed that shipments from the American plant would be shown originating at "Agatite",

a trade name used by American. A larger stumbling block to a lease agreement was

American's concern that their customer details might be unlawfully exposed to

Acme Plaster. American's shipments were being handled by the QA&P, headed by

Samuel Lazarus, who had previously been the owner of (and still held a large

financial interest in) Acme Plaster. The opportunity for subterfuge was too

great to ignore. American refused to allow the Acme Tap lease to be renewed by

the QA&P. Instead, they "permanently" leased it to the FW&DC.

While the QA&P continued

switching Acme Plaster, the

FW&DC began switching the American plant, with Acme Tap waybills

showing origination at Agatite. This arrangement remained stable for many years

until both plants came under the control of Certain-teed Products Company in the

late 1920s (at least in part due to the death of Samuel Lazarus in March, 1926.) Certain-teed began working to restructure the operations of the two

plants into a cooperative activity which would require moving rail cars between

them. Unfortunately, this would create an interchange charge "per car"

for movements between the plants since the QA&P and Acme Tap were separate railroads.

Certain-teed wanted the QA&P to switch both plants, but the FW&DC, controlling a

permanent lease on the Acme Tap, vehemently opposed the idea, suggesting that

they should switch both plants. When the railroads and Certain-teed could not

agree to a solution, the FW&DC raised the stakes by giving six months' notice

that they were terminating the QA&P's trackage rights into Quanah. The QA&P responded by requesting ICC

permission to build its own line between Acme and Quanah, which was granted in

January, 1930.

Rather than use the land they had acquired in 1909 on the

south side of the FW&DC, the QA&P acquired new right-of-way on the north

side of

the FW&DC. On it, they built a new line out of Acme toward Quanah. Just

under a mile and half

west of Tower 27, the tracks angled to the northeast for a mile and then turned

due east for a half mile. There they intersected the Frisco tracks about three

quarters of a mile north of Tower 27, at the north end of the Frisco/QA&P yard. This new track went into service in March, 1931, providing faster transit

through Quanah for trains operating between Floydada and Oklahoma

City because it bypassed Tower 27. The QA&P also extended its depot tracks in

downtown Quanah east to Tower 27 and connected them to the Frisco's tracks so

they could reach their depots without using the FW&DC's depot spur (since they

no longer had rights on it.)

As the Depression began to set in, Certain-teed closed the Agatite plant, eliminating the need for the Acme Tap. The QA&P continued

switching the plant at Acme and signed an annual agreement renewed each year to

lease the few remaining FW&DC-owned tracks at Acme. The agreement also gave

the QA&P the right to operate the Acme Tap

tracks if the Agatite plant ever reopened. It never did, and the

Acme Tap was dismantled in 1938.

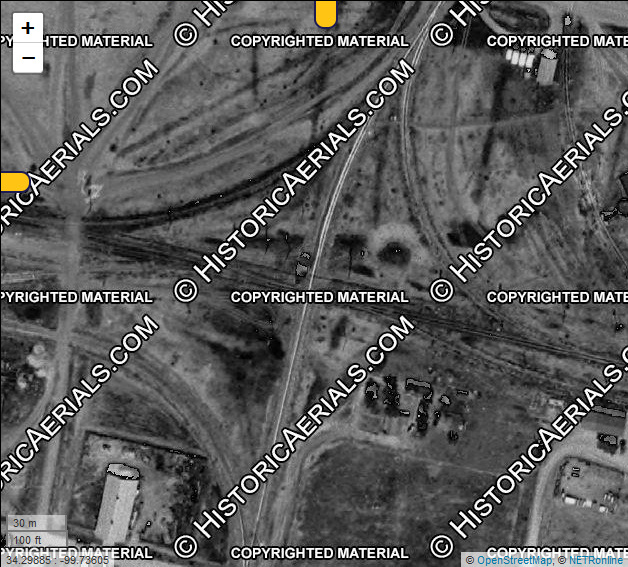

Above: These historic aerial images of the rail junction

near downtown Quanah show the changes between 1953 (left) and 1956 (right.) In

1953, the Frisco tracks still crossed the FW&D and went south down McClelland

St., off the bottom of the image. Tower 27 appears to be standing, but

the poor image quality prevents an accurate assessment. A 1953 FW&D Employee

Timetable lists some crossings as "Auto. Interlocked" whereas the

Quanah crossing is listed as merely "Interlocked", suggesting that the non-automated

(i.e. human operated) Tower 27 plant was still in use. By 1956, the Frisco

crossing of the FW&D had been removed and there's no apparent tower. There are

other track changes, one of which is a new track that crosses the FW&D left of

center, to the immediate left of a white equipment cabinet casting a shadow to

the north, presumably housing a new interlocker. A 1960 FW&D Employee Timetable

confirms the Quanah crossing has become "Auto. Interlocked" indicating the

interlocker design changed between 1953 and 1960. ((c)historicaerials.com)

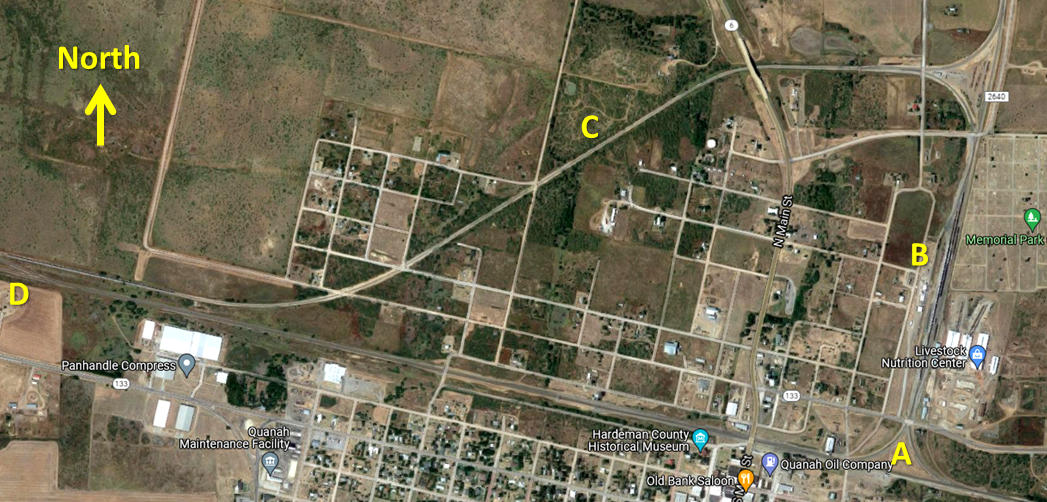

Below:

This annotated satellite image shows the track

arrangement at Quanah in recent times. A) Tower 27 was located in this vicinity

where the Frisco tracks coming south from the Red River crossed the east/west

FW&D tracks. There is no longer any satellite evidence that tracks previously

continued south of the tower. B) North of Tower 27, the QA&P/Frisco yard is now

used by BNSF. The line continues to the north into Oklahoma. C) The QA&P bypass

that opened in 1931 remains intact for BNSF. D) This connection between the FW&D

track (south) and the QA&P track (north) shows that the former QA&P line into

Quanah is now used as a lengthy passing track for the main line. There are no

other crossovers and the two lines do not reconnect until they reach Acme, six

miles to the west. Also of interest on this map, the location of the QA&P depot

which hosts the Hardeman County Historical Museum is marked by the light blue

teardrop.

The new QA&P tracks from Acme to Quanah were on the north side of the FW&DC while the tracks from Acme to Floydada were south of it. The QA&P had no choice but to cross over the FW&DC at Acme. This required an interlocker which was commissioned by RCT as Tower 171. Tower 171 is the first interlocker not to appear in a table of active interlockers published by RCT. The last entry in the table of interlockers (dated December 31, 1930) in RCT's 1931 Annual Report was Tower 170. Beginning with the 1932 Annual Report, the table was omitted. RCT records, however, do show that the construction between Acme and Quanah occurred in 1931, so it is likely that Tower 171 was commissioned that same year. Most likely, this was an automatic interlocker from the outset. A June, 1940 FW&DC timetable shows it as such, and in May, 1930, RCT had begun to authorize automatic interlockers, the first ones being at Plainview and Lubbock.

|

Left:

This map of Quanah, its railroads, and the terrain north and west of it

depicts the Acme Cement Plaster Co. and the Salina Cement Plaster Co. as

orange boxes labeled 'A' and 'S', respectively. The Acme Tap officially

ended at the Salina plant but there were additional tracks north of the

plant to reach gypsum mines along Groesbeck Creek. The QA&P spur to the

southwest of Tower 171 accessed a deposit of gypsite (gypsum mixed with

clay.) Below: When the private tracks were dismantled, some culverts were left behind.   Google Earth, 2019 |

Above: This recent satellite view of Acme shows the former Acme

Cement Plaster Co. is now a Georgia Pacific facility along South Groesbeck

Creek. The former QA&P right-of-way to Paducah (yellow arrows and dashes) is

visible going west from the Tower 171 crossing.

Below: The former QA&P bridge over South Groesbeck

Creek still exhibits the name and logo. (Google Street View, March 2013)

The QA&P served agricultural areas that generated

seasonal business, so it wanted the Santa Fe connection at Floydada as a means

of facilitating regular overhead traffic to help cash flow during the lean

months. QA&P management knew that local traffic was insufficient, that they

needed to be a link in moving freight between the Frisco and Santa Fe. Santa Fe

resisted the Floydada connection from the beginning, refusing to accede to any

connection at all. They compromised after an ICC hearing on the matter and both

railroads funded their own tracks to create the connection at Floydada which

opened on June 30, 1928. To Santa Fe, the exchange was only for local traffic,

hence they bitterly resisted

attempts to negotiate long haul tariffs via Floydada, preferring Avard, Oklahoma

as the only gateway for Frisco traffic. The QA&P fought back and refused to stop

soliciting such traffic. Though the numbers were not large, they continued to

mix non-local traffic into their interchanges with Santa Fe at Floydada. They

also agreed to use the same division of revenue that the Frisco would have

received for traffic through Avard. In their view, Santa Fe should welcome this

business since Santa Fe's haul west from Floydada was 194 miles shorter than

Santa Fe's haul west from Avard. Santa Fe's counterargument was that moving

freight between Floydada and their main line at Canyon required carrying it over

two branch lines that were not equipped to handle traffic of this nature.

Despite their objections, Santa Fe accepted the meager amount of non-local QA&P

traffic at Floydada and hoped it would go away. When it did not, they announced

in March, 1933, that they intended to close the Floydada gateway. They would

implement interchange restrictions by refusing to handle traffic that did not

originate or terminate on the QA&P, or on the Frisco south of Sapulpa and Enid,

Oklahoma. Everything else had to exchange at

Avard.

The QA&P filed a complaint with the ICC, but they lost the ICC's

regional examiner's adjudication in May, 1933. Undeterred, they re-filed their

case in more detail and with backing from the American Short Line Railroad

Association which viewed Santa Fe's actions as blatantly discriminatory against

a much smaller railroad. They lost again in late 1934 when ICC Division Four

examiners ruled 2 - 1 in favor of Santa Fe. Still undeterred, the QA&P filed for

reconsideration by the ICC's commissioners in Washington, DC, recasting their

argument as rate discrimination since the Floydada gateway wasn't completely

closed. In October, 1935, they lost once again when the full commission ruled in

favor of Santa Fe. Still undeterred (yes,

seriously...), the QA&P filed for rehearing and reconsideration by the

ICC's commissioners, again emphasizing the discrimination they were experiencing compared to Santa Fe's rates and divisions with

other railroads. For reasons known only to the ICC, they agreed to reopen and

rehear the case. In doing so, they requested substantial information from Santa

Fe regarding its connections and arrangements with other railroads at other

gateways. Santa Fe panicked; they did not want that kind of competitive data

released in a public setting such as an ICC examiner's hearing. But they had no choice, and

much of the information that came out during the hearing held in Oklahoma City

in October, 1936, bolstered the QA&Ps arguments. The ICC examiner found in favor

of the QA&P, and the ICC commissioners did also in February, 1938. By 1939, the Floydada gateway

was wide open to transcontinental traffic.

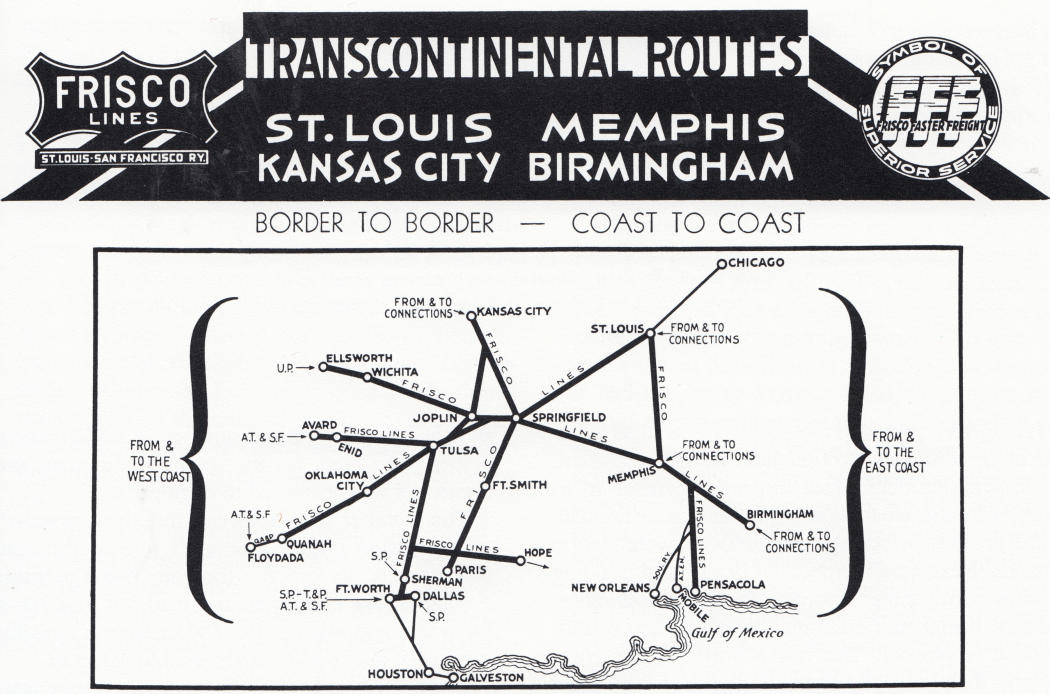

Above: The QA&P convinced

Frisco management to promote it as a critical link for transcontinental

routings. This ad showed how the Frisco was positioned to carry the middle segment of

transcontinental traffic, including separately depicting the QA&P and its

connection to the Santa Fe. Although Avard and Floydada both led to southern

California, Floydada certainly "looked" more appropriate for shipments headed

there!

(from

The Quanah Route, by Don L. Hofsommer, 1991, Texas A&M University Press.)

Floydada prospered reasonably well at the crossroads of a transcontinental rail link for the next three decades. Traffic maintained a steady flow, local citizens enjoyed better passenger rail options than most, and the local agricultural production moved efficiently to markets. Historic aerial imagery from 1957 shows a large triangular track arrangement in place on open land on the southeast side of town adjacent to the QA&P depot, near where the QA&P tracks arrived from the east. It appears that the QA&P had begun planning for some kind of large facility, or perhaps the tracks were laid to lure industrial customers to build there. Whatever the case, a new automobile distribution center was built beside the south track in 1959 with yard tracks installed for unloading vehicles. This enterprise brought new jobs and commerce to Floydada and substantial revenue to the QA&P and Frisco. The automobile distribution center expanded twice in the 1960s as additional carmakers sought to make use of it. By 1969, the facility was handling 3,000 cars per month, which likely had begun to include some of the initial wave of Japanese cars imported through the west coast and brought to Floydada by Santa Fe. Santa Fe eventually built their own vehicle distribution center in Amarillo.

|

|

When Chrysler teamed with the

Frisco to move automobiles by rail from St. Louis to the Dallas market, the success motivated

construction of a vehicle distribution facility at Floydada in 1959. Cars from Chrysler's factory near St. Louis arrived on the QA&P

and were then moved by truck to dealers across west Texas. The view at

left faces west

with the QA&P main line (and a Santa Fe exchange track beside it) entering

Floydada from the east near the bottom right corner. A switch on the QA&P sent auto racks to the

left down the south track of the wye to be moved into the facility for unloading.

The west track of the wye allowed reversing trains with empty car carriers

for the return trip to St. Louis. The east track of the wye led to the

QA&P depot and additional exchange tracks with Santa Fe.

(image from

The Quanah Route, by Don L. Hofsommer, 1991, Texas A&M University Press.) Above: Looking northwest, the rails are all gone at the east point of the Floydada wye, but the curvature remains implanted in the vegetation. The QA&P depot is long gone but might have previously been visible at the far right edge of this image. (Jim King photo, 1999) |

In 1959, Santa Fe, the QA&P and the Frisco initiated

twice daily transcontinental "hot shot" trains in each direction, with

locomotives and cabooses (and nothing else) being switched out at Floydada. This

required a few track changes to reduce transit delays since the original

connection there did not anticipate handling "through

trains." Among the changes, automatic interlockers were installed at

Lockney (Tower 212) and the east side of Plainview

(Tower 213.) The hot shot route also passed through

Tower 142 at Plainview.

Floydada's population

peaked in 1970 at around 4,000 and the local economy was good. It would not stay

that way. Santa Fe officials approached senior

management of the Frisco in the early 1970s to discuss closing the Floydada

gateway and moving all exchange traffic to Avard. Santa Fe did not want the

expense of upgrading the rail into Floydada which had become a maintenance issue. Floydada was a terminus for both railroads, so

the expense of maintaining the rails out of Floydada for

time-sensitive transcontinental freight was beyond what the local traffic alone in either

direction could justify. But at Avard, this was only true for the

Frisco. Avard was on Santa Fe's main line from Kansas City to Amarillo with rails maintained to a high standard.

For the Frisco, Avard was not much different than Floydada, a dead-end 175 miles west of Tulsa with little local traffic.

But critically, the route from Tulsa to Avard was easier, faster and much less

subject to delay compared to the QA&P. In the end,

the Frisco could not justify the cost of two transcontinental gateways with

Santa Fe. When they balked at giving up the automobile business at Floydada, Santa Fe

sweetened the offer by giving the Frisco a very favorable division of revenue

for any auto racks they routed to Santa Fe's vehicle distribution

center in Amarillo. Santa Fe also offered a better revenue split for all

exchanges through Avard as an additional incentive. A deal was struck in early

1973, and in August, the hot shots began running via Avard. Operations continued

on the QA&P, but during the off season, only a thrice-weekly local ran between

Quanah and Floydada.

Yet... the loss of daily

transcontinental traffic through Floydada was almost immediately replaced by a

deal between the FW&D, the QA&P and Santa Fe to run a daily FW&D train between

Acme and Lockney. A major derail on the FW&D tracks between Estelline and Sterley

had wiped out one of the two tunnels on that branch, necessitating extensive and lengthy repairs.

The temporary arrangement detoured FW&D trains between Acme and Lockney via Floydada to bypass the collapsed tunnel. At Lockney, FW&D trains returned to

their own rails south to Lubbock. The FW&D began talks with the Frisco

about acquiring the QA&P between Acme and Floydada rather than rebuild the

tunnel. The talks progressed to the point that a

deal was within reach. The FW&D needed Santa Fe to grant trackage rights on the

twelve miles of track between Floydada and Lockney that the FW&D had been using

for detours. This track was now lightly used since Santa Fe and the Frisco had

moved all of their interchange traffic to Avard. Everyone agreed to the deal,

including local Santa Fe management. Santa Fe senior management, however, chose

to kill the deal, not admitting, but apparently still harboring, animosity a

half-century later for the FW&D's invasion of the South Plains! The FW&D was

forced to repair their tunnel by "daylighting" what was left of it to be

able to resume operations on the branch at Estelline. The last detour train

was in January, 1975.

Long before the end of the 1970s, cattle shipping on the QA&P

had effectively disappeared, replaced by trucks on paved highways that had gradually

reached into the Caprock. This had contributed to reduced cash flow on the QA&P such

that the expense of maintaining operations to Floydada was becoming problematic. Burlington Northern (BN) had long owned the FW&D, and they

acquired the Frisco in 1980. New management was ready to cut costs, so

the QA&P tracks into Floydada were scheduled for abandonment. The last train

from Floydada to Quanah operated on May 5, 1981, and the 67 miles of track from

Paducah to Floydada was removed soon thereafter. Floydada fared little better in

the opposite direction. Santa Fe sold its Floydada branch line in 1990 and it was

abandoned in 1993. Floydada, the town that had four transcontinental freight trains

daily for more than a decade now had no trains at all.

In 1987, BN

abandoned the QA&P tracks between Acme and Paducah. The QA&P main line between

Acme and Quanah was retained to provide a long siding for BN beside the former

FW&D

main line. The QA&P had met its final demise. In 1996, BN merged with Santa Fe to form Burlington Northern Santa Fe

(BNSF.) The original FW&DC route from Ft. Worth to Amarillo remains in operation

by BNSF as do the former Frisco tracks north out of Quanah. BNSF

continued switching the Georgia-Pacific plaster and cement products plant at Acme

until it closed on March 1, 2023. Closing the plant could not have been easy for

Georgia Pacific's owner, Koch Industries, led by CEO Charles Koch. His dad Fred

was born in Quanah and founded Koch Industries. Fred's dad Harry was the owner

of the Quanah Tribune Chief newspaper.

Editor's Note: More than twenty years ago, I first researched the QA&P after reading Professor Don Hofsommer's book, The Quanah Route. I used it as an opportunity to get my dad out of his house for a road trip, something he always enjoyed. We drove the route, took some photos, ate a few greasy meals at diners, and generally enjoyed the trip and the scenery for a couple of days. When I returned, I compiled my information into an article for Clearance Card, the quarterly journal of the Southwest Railroad Historical Society. (I knew it would be accepted for publication because I was the Editor.) Because of the enormous debt I owed Professor Hofsommer's book, I researched his whereabouts and was able to determine that he was teaching at St. Cloud State University in Minnesota. Having no information beyond that, I mailed a thank you note and a copy of that Winter, 1999 issue of Clearance Card to Professor Hofsommer, care of the University's published address. I could only hope it would reach him. Three weeks later, you can imagine the shock I had when I opened my mailbox and pulled out a letter with my address typewritten on a Quanah, Acme & Pacific corporate envelope, more than a decade after the QA&P had ceased to exist. The letter inside, typed on QA&P letterhead, was a short thank you note from Professor Hofsommer. I finally had the privilege of meeting him and dining with him when he was the keynote speaker at the banquet of the NRHS national convention in Duluth, Minnesota in 2009. He explained that he had been given some corporate stationery during his research, and he still recalled sending me that letter ten years earlier. Special thanks go to Professor Hofsommer for his wonderful and detailed book about the QA&P.