Texas Railroad History - Tower 135, Canyon and Tower

188, Farwell

Two Junctions to Lubbock on the Panhandle

& Santa Fe Main Line

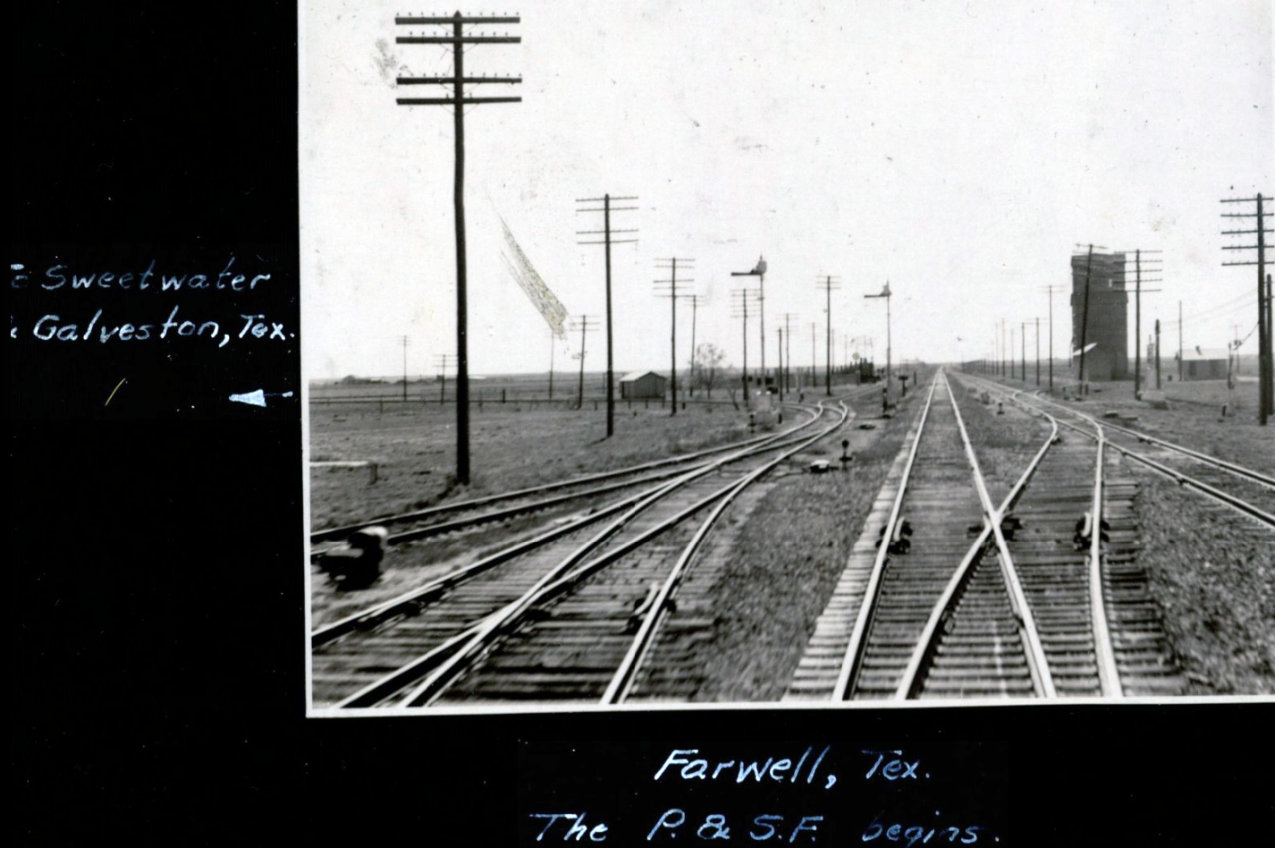

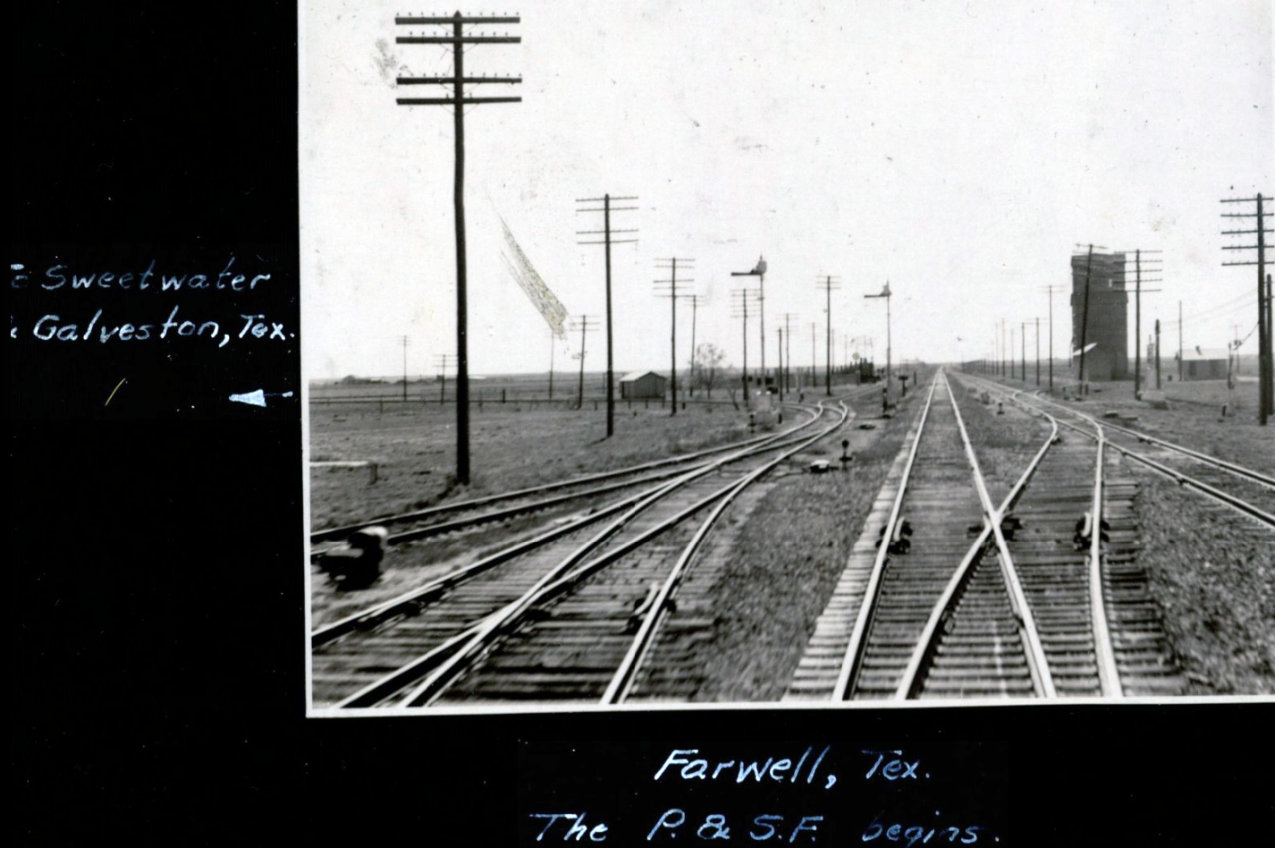

Above: On May 5, 1940,

railroad executive John W. Barriger III took this photo facing west from the

rear platform of his business car as his train proceeded eastbound on tracks of

the Panhandle & Santa Fe (P&SF) Railway. When Barriger went through his

developed film post-trip to make annotations, he mistakenly identified this

location as Farwell, a tiny Texas community at the New Mexico state line where

eastbound trains effectively transition from the Belen Cutoff onto the P&SF

("The P&SF begins.") Barriger's camera instinct had been provoked by tracks

coming in from the left to merge onto the Belen Cutoff (westbound) and the P&SF

main line (eastbound). Barriger's annotation notes that the junction leads to

Sweetwater and Galveston, hundreds of miles southeast of Farwell. The track to

the left does indeed lead to Sweetwater and Galveston, but the photo was not

taken at Farwell. It was taken at Lubbock Junction in Canyon, Texas, 77 miles

east of Farwell. The telling detail is that at Farwell, the track from

Sweetwater joins the P&SF at the beginning of a significant curve across the

state line into the community of Texico, New Mexico and the Belen Cutoff, a curve not present in this

photo. Unlike Farwell, the main line at Canyon remained perfectly straight as it

passed near and through the junction leading to Lubbock, Sweetwater and

Galveston.

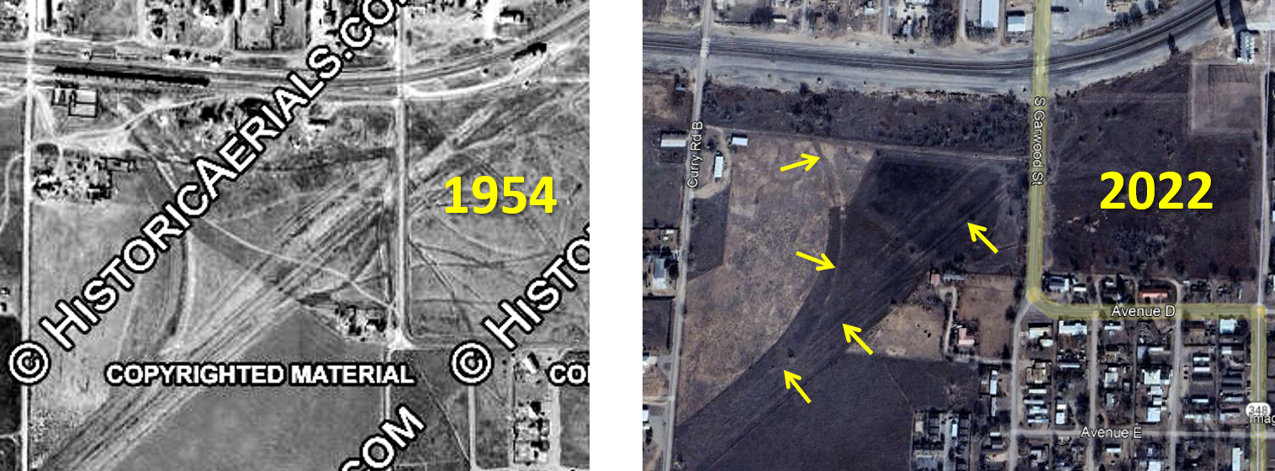

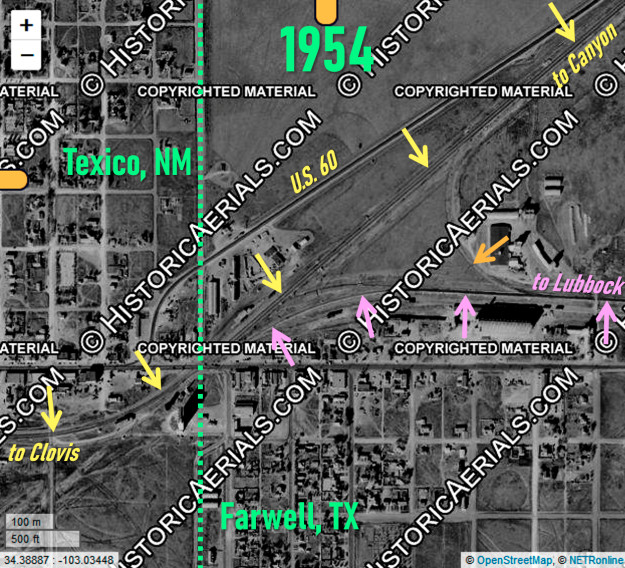

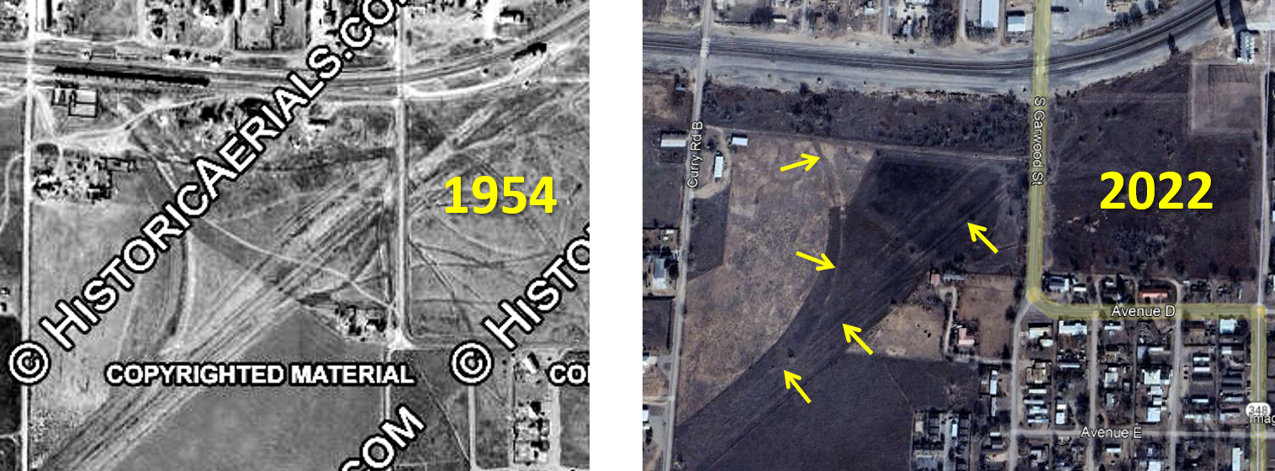

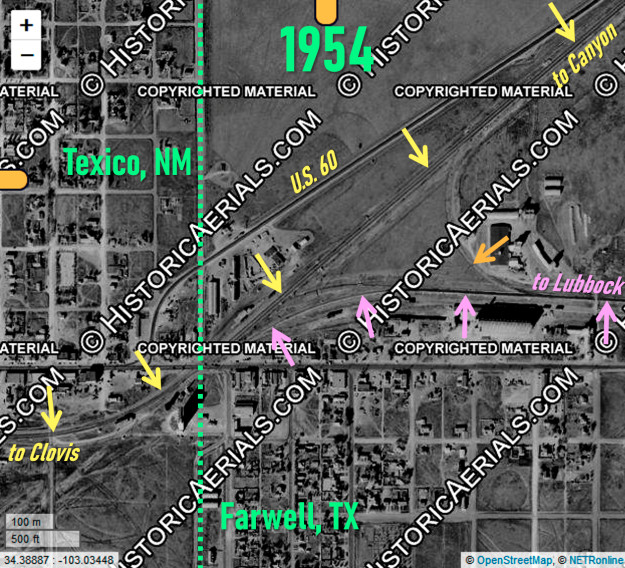

Below Left: This 1954 image

((c)historicaerials.com) shows the Santa Fe main line (yellow arrows) at the

Texas / New Mexico border (green dashes). On the Farwell side, the line from

Sweetwater and Lubbock comes in from the east (pink arrows) and crosses into

Texico, New Mexico followed immediately by a

curve to a due west heading toward Santa Fe's yard and maintenance base at

Clovis, nine miles farther west. This

curve is not present in Barriger's photo above, clarifying that his Farwell annotation

was a mistake. A connecting track (orange arrow) for the opposite direction

supported switching movements for local freights. Below

Right: This 1953 image ((c)historicaerials.com) of Lubbock

Junction at Canyon shows the P&SF main line (yellow arrows) running due east /

west on the west side of town. The line from Lubbock and Plainview (pink

arrows) approaches from the south on a nearly due north heading. It is apparent

from the image that the east connecting track (orange arrow) was being

maintained to a much higher standard than the west connector (blue arrow) due to

frequent movements on the east connector for Amarillo / Lubbock traffic.

Above: Looking north

from the 4th Avenue grade crossing in

Canyon, this Google Street View image from May, 2013 shows that the track into Lubbock Junction

now splits south of 4th Avenue; in the 1953 image above, the switch was barely

north of 4th Avenue. The west (left) connector appears to be in better shape

than it was in 1953 but still not maintained to the same quality as the east

connector. In the

distance, an intermodal train is passing through Canyon on the former Santa Fe

main line, now owned by Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF).

Below Left: Looking south from

the same location as above, the connectors combine into a single track going south to

Plainview and Lubbock, continuing to Sweetwater and Galveston. The "straight through" route is the east connector which

is used for Amarillo / Lubbock traffic.

Below Right: As noted by the sign on the left side of

the image, this Google Street View (March, 2022) was captured at "Lubbock Jct."

in Canyon. It was taken from the 4th Street grade crossing facing due west

toward Farwell, 77 miles distant. The switch visible on the south (left) track

across from the equipment cabinets on the right is the east connector leading

south toward Plainview and Lubbock. The corresponding west connector is barley

visible in the distance curving onto the south track. The large pink building

trackside at right might be the same building in Barriger's photo at top of

page, or perhaps a successor.

|

Left Top:

This Google Street View from October, 2021 was taken from the U.S. Hwy

84 grade crossing over the BNSF tracks at the New Mexico / Texas state

line. The camera is facing northeast into Texas toward the tail end of

an intermodal train that is passing through Farwell on BNSF's double

main line toward Canyon and beyond. The track curving to the right is

the line to Lubbock, Sweetwater and Galveston. It

opened in March, 1914 when it was known as the Lubbock - Texico Cutoff.

Left Bottom:

This view in the opposite direction faces southwest into Texico, New

Mexico. It was captured simultaneously with the image above by Google

Street View. The major yard at Clovis is about nine miles distant around

the bend of the curve which takes the line to a due west

heading. Notice that the Lubbock track (far left) no longer intersects the main

line here. Instead, it continues for nearly two miles before finally

merging onto the south track. Before the Belen Cutoff opened in

1908, there

was no curve here at all. The tracks simply continued southwest on a

direct heading for Portales and Roswell. Now, those towns are reached by

a track segment running 8.7 miles due south from Clovis that intersects

and curves to the southwest to rejoin the tracks on the original right-of-way to Portales. |

Canyon was named for its proximity to the spectacular

Palo Duro Canyon.

Originally known as Canyon City, the town's humble beginnings were in a dugout built by Lincoln

Connor c.1887, his home also serving as a general store. With the organization

of Randall County in 1889, Canyon became the county seat. By 1896, a weekly

newspaper had survived long enough to be published regularly (becoming known as

the Canyon City News in 1903.) The town received

rail service in 1899 when the Pecos & Northern Texas (P&NT) Railway

laid tracks to Amarillo from Farwell on the New Mexico state line,

the Texas portion of a lengthier route originating in Roswell, New Mexico.

The P&NT was the brainchild of noted railroad developer James J. Hagerman

who had decided to build northeast from Roswell.

Hagerman was an industrialist known best for developing mines and railroads in

Colorado, New Mexico and Texas. [He does not appear to have been directly

related to James Hagerman, the General Solicitor for the Missouri, Kansas &

Texas Railroad who was active in railroading at the same time.] In 1890, Hagerman built the Pecos Valley Railroad

between Pecos, Texas and Roswell (legally chartered on the Texas side of the

border as the Pecos

River Railroad.) Hagerman expected agricultural products from the Pecos

River Valley near Roswell to find commercial outlets in

Fort Worth and El Paso via the Texas & Pacific

(T&P) Railway connection at Pecos. The results were disappointing and Hagerman came to understand that the proper outlet for Pecos

Valley crops and livestock was the Midwest. By 1896, he had begun

planning a lengthy rail line from Roswell to the Texas Panhandle. His objective

was to make a connection with the Atchison,

Topeka & Santa Fe (AT&SF) Railway through its Texas subsidiary, the Southern Kansas Railroad (SKR).

SKR tracks in the Panhandle led northeast through Oklahoma into Kansas,

eventually reaching the major Midwest rail junction at Kansas City.

The obvious

SKR connection for Hagerman was at

Washburn, a tiny community fifteen miles east-southeast of Amarillo. The SKR's

nearest tracks were fifteen miles northeast of Washburn at Panhandle City, but

years earlier, the Panhandle Railway had been built between the two towns.

Washburn was significant only because it was on the Fort Worth & Denver City Railway (FW&DC, but mostly just FW&D

-- "City" was formally dropped in 1951.) The FW&D had leased the

Panhandle Railway when Washburn was being promoted as a major future rail junction serving the FW&D and

Santa Fe. In 1891, Santa Fe had begun looking at routes out of Washburn toward the South Plains of the Texas Panhandle

and into New Mexico, stoking

the fires of Washburn's promoters and landowners. Santa Fe chose not to build

beyond Washburn; instead it agreed to

help Hagerman finance his line to the Texas Panhandle. Hagerman followed up on Santa Fe's

prior discussions with Washburn landowners, requesting a $20,000 bonus and half of the

townsite in exchange

for creating what would undoubtedly become the major railroad junction in the

Panhandle. Washburn negotiators drove a hard bargain, willing to grant

right-of-way (ROW) for tracks and land for depot facilities, but nothing else.

In their view, Hagerman had no other option. In railroad circles, it was known

that Hagerman preferred to connect at Amarillo, the commercial center of the

region, but the SKR had no tracks at Amarillo.

At some unknown date (and

certainly no later than the summer of 1897), Amarillo civic leaders got

wind of Hagerman's plan to connect at Washburn and were absolutely

flabbergasted at the possibility that a major railroad, Santa Fe, would

bypass Amarillo -- a much larger town than Washburn -- by

only fifteen miles. Amarillo dispatched local attorney Squire

Madden to meet with Santa Fe officials at

their Chicago headquarters. The date of this meeting is undetermined;

the Handbook of Texas asserts that it

was sometime in 1896. Madden's mission was successful; Amarillo agreed

to pay $20,000 for the railroads to change their connecting point, even

though Santa Fe had no tracks at Amarillo. Santa Fe did, however, have

trackage rights on the FW&D between Washburn and Amarillo, rights the

FW&D had sold only because it expected Santa Fe's major junction to be

at

Washburn. Instead, Hagerman's railroad would connect with Santa Fe at

Amarillo and the FW&D tracks would carry Pecos Valley traffic on

Santa Fe trains between Amarillo and Washburn.

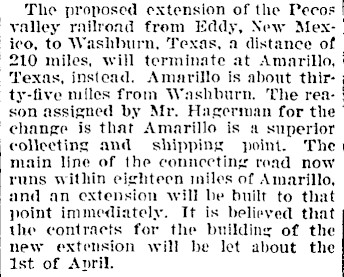

Right: This article in the

Fort Collins (Colorado) Courier of

March 24, 1898 narrows the timing of when Hagerman changed the

connecting point to Amarillo (only fifteen miles from Washburn, not

"thirty-five.") The decision was probably made a few months earlier in

the latter part of 1897, time used for revising the ROW and securing

easements. As for the extension between

Amarillo and "the

main line of the connecting road" (Santa Fe's terminus at Panhandle City), it was built

"immediately" ... if "immediately" means "ten years from now". |

|

|

Modifying the alignment for a direct route to Amarillo from the New Mexico

border would have meant bypassing Canyon City. Instead, the route was maintained

into Canyon City and then revised abruptly north toward Amarillo. In

A Branch Line Comes of Age, Part

Two, author Bob Burton explains why the route through Canyon City was retained:

Southwest of Amarillo

there was a choice of a direct route passing north of Canyon or of a longer line

through that town. Landholders at Canyon and southwards threatened to deny water

to the railroad if it missed Canyon, so the longer route was chosen.

Hagerman proceeded to obtain a Texas railroad

charter in 1898 for the P&NT which would own the Texas portion of his route as

required by state law. From a Pecos River crossing near Roswell, Hagerman's

original survey had planned to maintain a general 55-degree heading for 200

miles to Washburn, a heading that would pass through Canyon and proceed

northeast

along the north side of Palo Duro Canyon. Where the ROW crossed into Texas, the surveyors

elected to stay north of the Tierra Blanca Creek drainage which brought

the line slightly farther north than needed for the route into Canyon. Near Umbarger,

the heading was adjusted slightly to the east toward Canyon; a second adjustment

on the outskirts of Canyon sent the right-of-way due east through town.

Instead of continuing toward Washburn, the

revised ROW out of Canyon turned north to Amarillo, which the P&NT reached in 1899.

While the P&NT owned the tracks in Texas,

they were operated by a railroad Hagerman had reorganized from his Pecos Valley

Railroad for the new line, the Pecos Valley and Northeastern (PV&NE). Santa Fe bought all of Hagerman's Texas and

New Mexico rail interests in 1901, and several years later, elected to use

the P&NT charter for track expansion into the South Plains.

Right: Construction of "The Railroad South"

began in February, 1906. (Canyon City

News, February 16, 1906)

With the P&NT in its

fold, Santa Fe wanted to build into the South Plains

region south of Canyon, a cattle ranching area with increasing production of

wheat and cotton.

Plainview and Lubbock were the only towns of any

size; both were small and neither had rail service.

Plainview had been founded c.1886 through the efforts of two settlers, Z. T.

Maxwell and Edwin Lowe, who had simply decided to establish a town near their

land. Lubbock was another 42

miles farther south, the county seat of Lubbock County. It had been founded by

land promoters in 1891, although a Lubbock Post Office had been granted for a

tiny outpost in the county in 1884. |

|

|

|

|

Left: The

Canyon

City News of Friday, January 4, 1907 reported the arrival of

the first train into Plainview the prior Saturday, December

29, 1906. Note that the "officials" were from the "Pecos Valley"

(PV&NE),

i.e. the P&NT simply held title to the tracks Hagerman had built in Texas;

it was

the PV&NE (based in New Mexico, owned by Santa Fe) that actually used them.

PV&NE operations over the P&NT persisted until 1914 when the SKR was renamed the Panhandle & Santa

Fe (P&SF) Railway. All of Santa Fe's west Texas operations

(including the PV&NE's operations on the P&NT) were consolidated

under the P&SF.

Since the P&NT owned the majority of the tracks the P&SF was using, it was

leased to the P&SF and then formally merged in 1948. The P&SF was merged

into the parent AT&SF on August 1, 1965. |

|

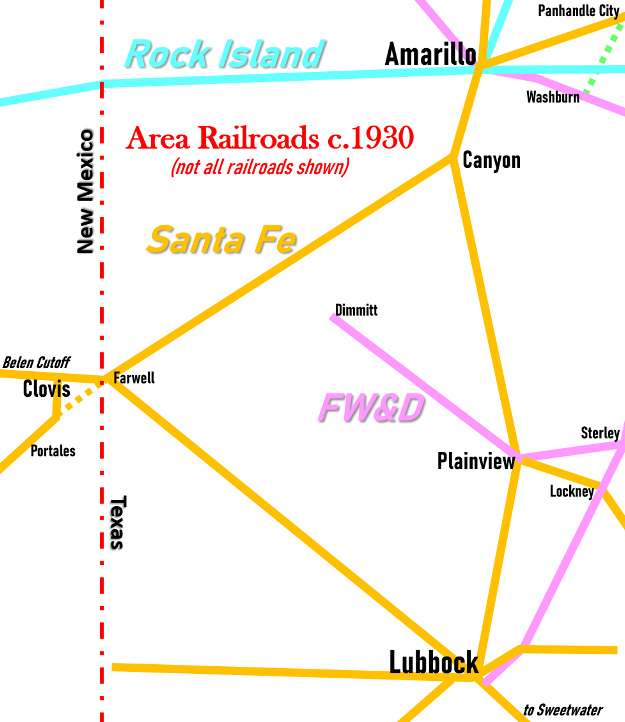

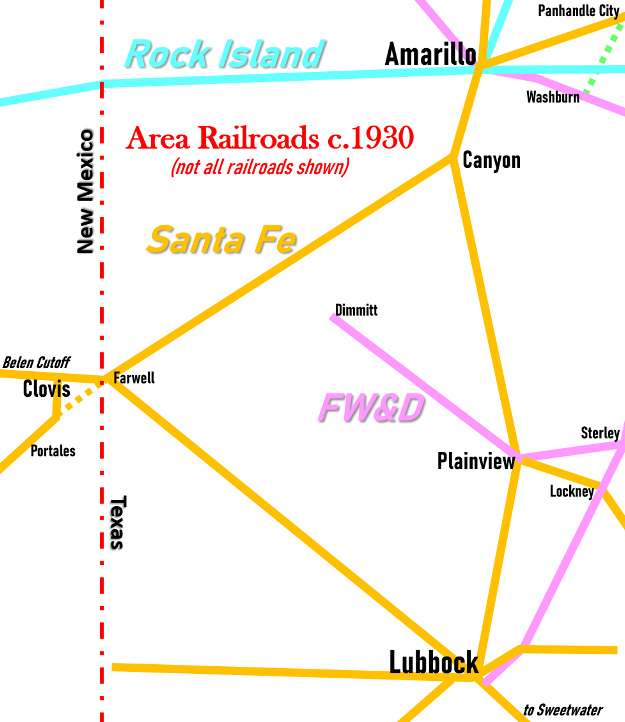

Left: Railroads

in the Amarillo - Lubbock - Clovis triangle c.1930

In 1908, Santa Fe

opened the Belen Cutoff which intersected the Roswell - Amarillo main

line at Farwell. The Cutoff

provided a shortcut for Kansas City / Los Angeles traffic across eastern New

Mexico to connect with Santa Fe's Los Angeles

main line at Belen, south of Albuquerque. West coast traffic began moving between Belen

and Kansas City via Farwell and Amarillo instead of the existing route through Raton Pass on the New

Mexico / Colorado border. The new town of Clovis was

established in 1907 by Santa Fe to host major switching and

maintenance facilities. To coincide with the opening of the Cutoff, Santa Fe rerouted the PV&NE to turn north into

Clovis. (Clovis had not been bypassed -- it simply didn't exist when the original line

through Farwell had been built

in 1899.) Santa Fe proceeded to abandon the tracks between Farwell and the

connecting point south of Clovis (orange dashes.)

The opening of the Belen

Cutoff also coincided with Santa Fe commencing operations on a new track

extension from Panhandle City to Amarillo. Ten years earlier, the SKR had leased the

Panhandle Railway and then acquired it in 1900. Pecos Valley traffic

destined for Kansas City had been making the jog from Amarillo to

Washburn to Panhandle City since 1899, but the jog through Washburn would

not be appropriate for the substantial increase in traffic

that the Cutoff would bring. The Panhandle Railway was

immediately abandoned (green dashes), and Tower

48 at its Rock Island crossing was closed.

In its

construction report to the Railroad Commission of Texas (RCT) for 1908,

the SKR officially noted that the extension from Panhandle to Amarillo

involved 24.66 miles of track, although this might have included

additional tracks in the Amarillo area. For such a small length of

track, it seems odd that Santa Fe waited so long to extend the SKR from

Panhandle City. By this time, the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific had built through Amarillo,

adding another railroad to be crossed in addition to the FW&D. An

interlocking tower was required, and Tower 75 was commissioned by RCT

at Amarillo in

July, 1908.

Having reached Plainview, the Santa Fe resumed P&NT construction southward in early 1909,

reaching

Lubbock late that year. A branch line from Plainview to Floydada via Lockney was

built, and others were built or acquired by Santa Fe in the Lubbock

area. A major factor in building to Lubbock was the

opportunity for a connection to Santa Fe's Galveston-based

subsidiary, the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe (GC&SF) Railway. The GC&SF's construction

northwest from Temple had terminated at Coleman in

1885, nearly two hundred miles southeast of Lubbock. Surveyors began working on a northwest route out of

Coleman in 1909, bypassing downtown Abilene through nearby Buffalo Gap

and then proceeding to cross the Texas & Pacific main line at

Sweetwater. Trains between Temple and

Sweetwater were operating by November, 1910. The

Snyder Signal of Friday, May 19, 1911

reported that "the first through train on the Santa Fe between Sweetwater and

Lubbock passed through Snyder Sunday." |

The connection to the GC&SF through Sweetwater

facilitated direct service between California and the Houston / Galveston area

via the Belen Cutoff and Farwell, Canyon and Lubbock. Santa Fe quickly

began planning to build a direct

line between Lubbock and Farwell to further shorten the route. Known in the press

as the Lubbock - Texico Cut Off, construction began in 1912 from both

endpoints. The track was initially completed in November, 1913, but telegraph

lines, water stops and additional ballasting delayed the official opening until

March 1, 1914. This was exciting news in Galveston which stood to gain faster

service to and from the west coast. The Galveston

Tribune of February 19, 1914 quoted the Los

Angeles Examiner commenting that the new cutoff would save "...more

than 100 miles of the distance between this city [Los Angeles] and the gulf port, and with the

direct connection, will mean a saving of 24 hours in time."

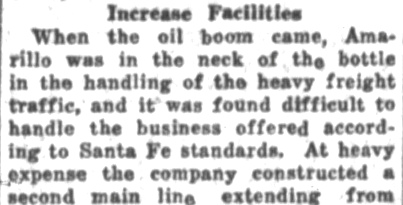

Right: Looking back on Santa Fe's investment in

the Panhandle, the Amarillo Sunday

News-Globe of January 12, 1930 discussed the impact of the

region's oil boom on the railroad.

In 1910, oil and gas was

discovered in the Texas Panhandle. As the fields were developed,

significant volumes of heavy rail traffic moved through Amarillo, much

of it carried by Santa Fe. In the 1920s, Santa Fe

decided to install a second main track between Canyon and

Pampa to improve traffic flow through

Amarillo. Santa Fe installed interlockers to manage the transition

between single and double tracks at

both Canyon and Pampa. |

|

|

The track north into Canyon from Plainview and Lubbock intersected the

Amarillo - Farwell main line on the west edge of town at Lubbock Junction.

The simple east and west connections with the single-track P&SF main line

became more complex when Santa Fe laid the second main track between

Pampa and Canyon because the double track extended far enough west to include

Lubbock Junction. Santa Fe decided to use an interlocking plant to manage

the transition between the main line single and double track and to control

switches and signals associated with movements on and off of the Lubbock /

Plainview line. Although Canyon did not have a large yard, there may also have

been yard siding switches that were included among the interlocking's functions.

As RCT became aware of Santa Fe's

efforts to manage the tracks on the west side of Canyon,

its engineering staff inquired as to when they could expect to see the

interlocker plans. In a

letter dated October 12, 1927, P&SF responded to RCT stating

"...it was not our understanding that plans

should be filed with the Commission when an interlocking plant was constructed

merely for the purpose of handling trains in and out of a junction point and no

other railroad involved." RCT responded that

it had never interpreted its policy as having any restriction on its

authority to approve all interlockers. The precedent had already been set for

single-railroad yard interlocking plants to be approved by RCT with the

commissioning of

Tower 121

in 1925, but it was an actual tower structure

built to house the interlocker controls and operators. Since the system at

Canyon would be remote controlled with no tower structure,

RCT's response to Santa Fe

established that its approval policy was to be enforced for all interlocking plants

regardless of local or remote control, or whether a second railroad company was

involved. Shortly after RCT's

response, P&SF submitted the required documentation. Santa Fe's interlocker

at Canyon was then designated Tower 135 by RCT and authorized for operation on

December 9, 1927. It initially had 27 functions, a number indicative of the

complexity of the Lubbock Junction intersection and the

nearby transition between double track and single track.

|

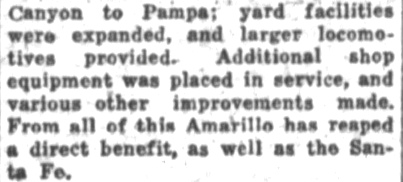

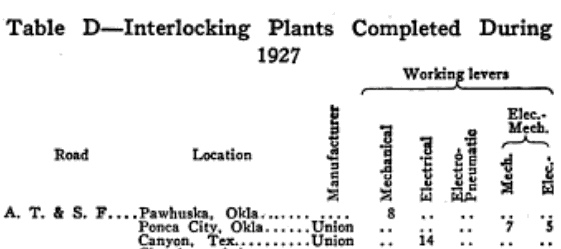

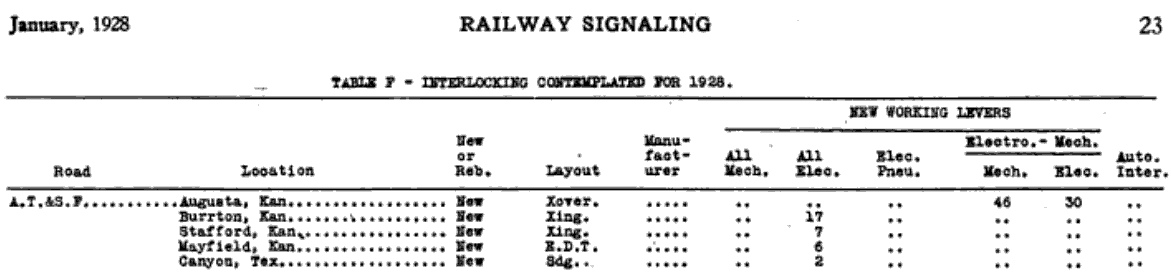

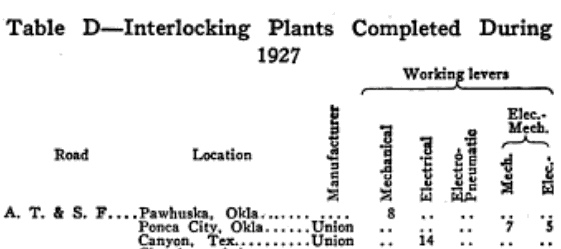

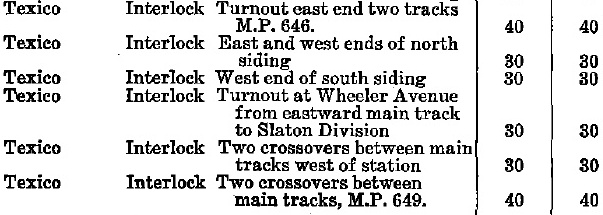

These two tables appeared in

the January, 1928 issue of Railway

Signaling. The table above

lists "Interlocking Contemplated for 1928" for Santa Fe. The last entry

in the list projects two new working levers (to be "All Elec.") for Canyon that

would support a "Sdg." (siding) layout. The table at

left shows that in

1927, an interlocking plant built by Union Switch & Signal had been

installed at Canyon with fourteen working levers controlling functions

electronically through the plant. This implies that the two new levers

projected for 1928 were in addition to those installed at Canyon in

1927. Although RCT lists Tower 135 with 27 initial functions, there is

not a one-to-one correspondence between working levers and functions. It

was common for the total function count to exceed the number of working

levers because paired functions (i.e. those with a fixed relationship)

could be controlled by the same lever. For example, a "Proceed" home

signal control might be paired on a working lever with a control to

disengage the associated derail. |

Tower 135's function count increased to 33 in 1928, presumably associated with

the additional "Interlocking Contemplated for 1928" reported by

Railway Signaling. The count remained at that

number through the final public report issued by RCT on December 31, 1930. The use of an electric interlocker

allowed the controls to be remoted to a facility, e.g. a yard office or depot,

for use by operators (and there were operators

-- automatic interlockers were not allowed in Texas until Tower

141 opened at Lubbock in 1931.) The controls might have been handled by

operators at Santa Fe's regional office in Amarillo; a remote control distance of ~ 20

miles was not unprecedented by the late 1920s.

Tower 135's approval was a significant event in the history of

RCT interlocker management. From this point on, all railroads were

officially on notice that all interlockers required RCT approval, regardless of

their purpose or whether other railroads were involved. RCT's rigid stance

suggests that the agency was trying

hard to justify its continued regulatory relevance. The Transportation Act of

1920 had given vast power to the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to manage

every aspect of railroad operations. The ICC's jurisdiction covered routes and

mergers, but also specific signals and derails. It was ICC approval that railroads sought, even

for simple signal changes, and its rulings took precedence over RCT decisions in

the event of a conflict. Ultimately RCT extended its approval policy to include more

sophisticated control systems such as Centralized Traffic Control (CTC), but advances in

railroad signaling and management systems quickly surpassed the ability of

RCT's limited engineering staff to do any legitimate technical assessment.

RCT's regulatory power over the enormous Texas oil and gas industry was not

subject to Federal oversight, hence the oil and gas side of RCT had begun to

receive the bulk of its staff resources. With the

railroad side diminishing in importance, RCT ended oversight of interlockers in

the mid-1960s; the last to be numbered and approved was Tower 215 at

Bloomington c.1966.

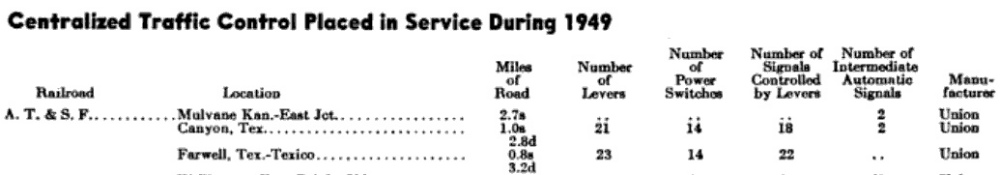

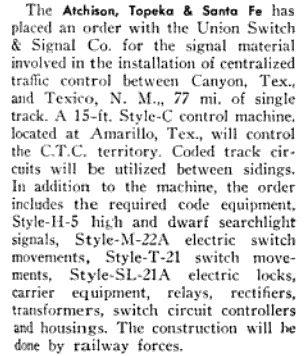

Right: (Railway

Age, April 10, 1948) In the late 1940s, Santa Fe

prepared to install CTC between Texico, NM

and Canyon. As noted in the news item, this was "77 mi. of single

track" establishing that the second main track installed into

Canyon in the mid 1920s had not been extended farther west. Instead, two

decades later Santa Fe decided to install CTC to improve operations on

the single track.

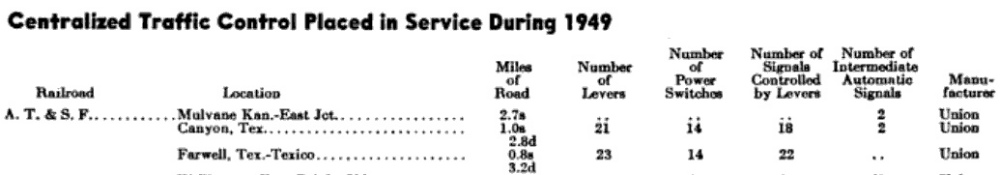

Below:

Railway Age, January 7, 1950

-- these short segments of CTC installed in 1949 probably represent the

integration of the new CTC with the double track present at both Canyon

and Farwell. The 's' and 'd' subscripts are for single and double track,

respectively.

The timing

of the CTC installation at Farwell tends to rule out the possibility

that this was the origin of Tower 188. The association of Tower 188 with

Farwell is assumed from the research performed by Southern Pacific

employee William J. Neill in the 1986-87 timeframe, but the source

material produced by that research has not been detailed. Tower 188

should have been installed in the early to mid 1940s based on the

installation timing for other known interlockers. |

|

Assuming that Tower 188 was indeed an interlocker at Farwell, examining the

timing of other known interlocker commissioning dates tends to place Tower 188's

installation in the early 1940s. There's no guarantee that interlockers were

installed in their numerical order, but they did tend to fall within similar

date ranges. Complexity and local factors sometimes caused interlocker design

and construction to deviate, resulting in "out of order" installations. There

were special cases, but in general, an interlocker usually became operational

within 6 to 18 months of receiving a number assignment, placing its

commissioning date in the range with interlockers having nearby tower numbers.

The variance tended to fall significantly after 1930 because the

number of new interlockers was declining and virtually all of them were

automatic interlockers which did not require construction of 2-story manned

towers. A hearing was held by RCT on October 30, 1942 to approve the Tower 189

interlocker, so it is reasonable to assume that it was installed in 1943. This

would tend to place the commissioning date for Tower 188 in the 1942-1944

timeframe.

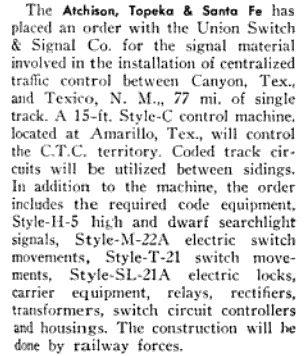

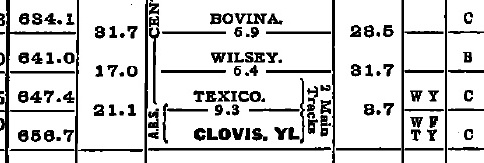

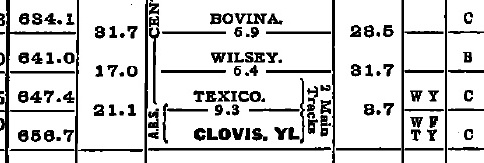

| Right:

This image is taken from Santa Fe's Plains Division employee timetable

dated April 2, 1950. It shows the Texico entries from a table of speed

limits to be followed when passing through switches and interlockings.

The table lists six interlocked locations at Texico with various speed

limits in miles per hour (for passenger and freight trains,

respectively.) The larger table has no Farwell entries; Santa Fe used

Texico as the common reference for operations at the state line,

regardless of which side. In particular, the first entry identifies an

interlocker at the "east end two tracks M.P. 646", a milepost located in

Farwell. The fourth entry indicates that the turnout from the east main

track to the Slaton Division (line to Lubbock) was interlocked at

Wheeler Ave., another name for U.S.

60 on the New Mexico side of the border. This Wheeler Ave. connection no

longer exists; the Lubbock line now extends west into New Mexico two

miles before connecting to the main track. |

|

|

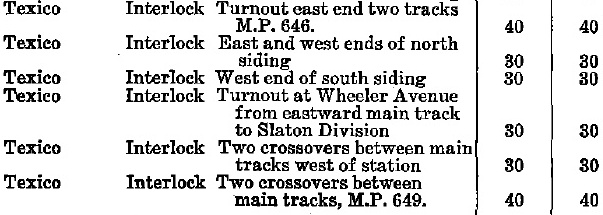

Left: This

image from the same timetable shows that Texico was located at

M.P. 647.4, hence M.P. 646 was 1.4 miles east of Texico, i.e. far enough

into Farwell to include the junction at the border with the Slaton

Division track to

Lubbock. This make sense; the same approach was used at Canyon to

include Lubbock Jct. within the interlocking. The interlocking affected

tracks in Texas hence there was jurisdiction for it to be incorporated

into RCT's interlocker management protocol as Tower

188 at Farwell. Whether the interlocking plant was located physically

within Texas is undetermined. It was most likely an automatic

interlocker, technology that had become common in Texas by the early

1940s. The timetable also notes "2 Main Tracks" between Texico and

Clovis. The second track likely precipitated the need for Tower 188. |

Virtually identical information as above also appears in a Santa Fe timetable

dated June 2, 1946 which indicates that the double track between Farwell and

Clovis was in place by then. The information does not

appear in a Santa Fe timetable dated July 5, 1942, i.e. there was not yet a

second main track between Farwell and Clovis. A 1942 - 1946 timeframe for the

installation of the second main track aligns with the likely date of the Tower

188 installation based on its tower number. It is reasonable to assume that the

second main track was activated once the interlocking was in place to arbitrate

access to and from the single track to Canyon. As noted earlier, that single

track was outfitted with CTC in 1949. An article in

Railway Signaling from March, 1929 states that Santa Fe had placed an

order for "block signaling material" to be installed at various places

including "Canyon, Tex. to Fort Sumner, N.M., 146.4 miles single track".

Since Fort Sumner is sixty miles west of Clovis, this indicates that the plan at

that time was to continue with only a single track west of Canyon through

Clovis, at least as far as Fort Sumner.

Above: John W.

Barriger III took this photo from the rear platform of his business car as his

train proceeded north out of Canyon toward Amarillo. The photo was taken on May

5, 1940 shortly after he took the photo that appears at the top of page. His

view is nearly due south toward Canyon, his train having completed the big curve

on the east side of town about three quarters of a mile distant from Barriger's

vantage point. The curve sent the tracks north toward Amarillo instead of

continuing northeast to Washburn on the original P&NT survey. Barriger's

location is known with some precision because his car has just passed over Palo

Duro Creek on the bridge in the foreground. The large size of the buildings in

the distance and the elevated terrain in that direction makes them appear closer

than they really are. They comprise part of West Texas State Teachers College,

the new name applied in 1923 to what had been West Texas State Normal College

when it opened in 1910. (It is now known as West Texas A&M University.) Per historic aerial imagery, the tracks have passed on this

side (north) of all of the University's buildings since at least since 1953, and this was probably

also true in

1940.

Below:

This recent Google Earth satellite image of Canyon shows a track layout

through town that remains essentially unchanged since 1906. The wye that forms Lubbock

Junction is prominent on the west (left) side of town, with the BNSF main line

passing due east / west through it. Closer to downtown, the track adjusts to a

slight northeast heading and then begins the large curve to the north toward

Amarillo. The university's sports complex consisting of a football stadium,

practice fields, a soccer stadium and a baseball stadium are visible in the

upper right corner.

Below: These aerial / satellite images of Texico show

that the original ROW continued straight southwest toward Portales on the same

general heading as the P&NT main line from Canyon. The prominent visibility

in 1954 ((c)historicaerials.com) of the original grades suggests that after the

curve onto the Belen Cutoff was built in 1908, some of the original tracks in

Texico may have been retained as a small yard or perhaps simply a wye. If there was still a main line connection

in 1954, it

is difficult to see. Portions of the original grades remain visible on Google

Earth satellite imgery in 2022, but there is no trace of them to the southwest

between Texico and where the tracks on the original ROW resume.