Texas Railroad History - Tower 103, Chaison (Beaumont)

and Tower 120, Port Arthur

Two Crossings of the Texarkana & Fort

Smith Railway by Spur Tracks of the Texas & New Orleans Railroad

Above:

Richard Day took this photo of Tower 103 at

Chaison in 1964. Richard explains ... "The view is

looking southwest down the SP industrial spur. To the right is the KCS main to

Beaumont and to the left is the KCS main to Port Arthur. The locomotive is a KCS

northbound switch job returning to the new yard recently completed across from

Lamar University. At this time, semaphores still controlled the KCS main

with short staff light signals controlling the SP main (one of these can be seen

in the view)." |

In

1896, the Texarkana & Fort Smith (T&FS) Railway built 19 miles between

Beaumont

and Port Arthur, a new town founded on Sabine Lake by Arthur Stilwell. The

construction was part of

his grand plan to build a rail line south from Kansas City to the Gulf of

Mexico. Service between Kansas City and Port Arthur began on November

1, 1897. The Texas & New Orleans (T&NO) Railroad, a subsidiary of Southern

Pacific (SP), already served Beaumont and also had tracks from Sabine Pass (on

the Gulf) to Beaumont that ran within three miles of downtown Port Arthur. Both

railroads built tracks to serve the industries along the shores of

Sabine Lake and the Neches River. The T&NO had tracks near the

Neches in Beaumont, but its line to Sabine Pass ran a few miles west of

the river. An oil refinery was built c.1903 along the river south of Beaumont,

and was served by the Kansas City Southern (KCS) Railway which had leased the

T&FS. To reach the refinery, the T&NO built a three mile spur that crossed

the T&FS main line at "Chaison", a location subsequently interlocked as Tower

103.

Robert Casares

notes the

Union Switch and Signal miniature block occupancy indicators in the

image at left. "The difference is that they have a larger block than

wayside signals, on a scale of about 3 to 1. When the block is empty,

the circuit charges the coils and causes the indicator to be in the

lower position, or 'clear'. When a train enters the block, it short

circuits the device, as there is less resistance going through the

wheels than the track circuit. When that happens, the coils de-energize

and the indicator falls into the horizontal position. When a motor car

or speeder operator sees that, they know that they need to remove their

track car from the rails ASAP." |

|

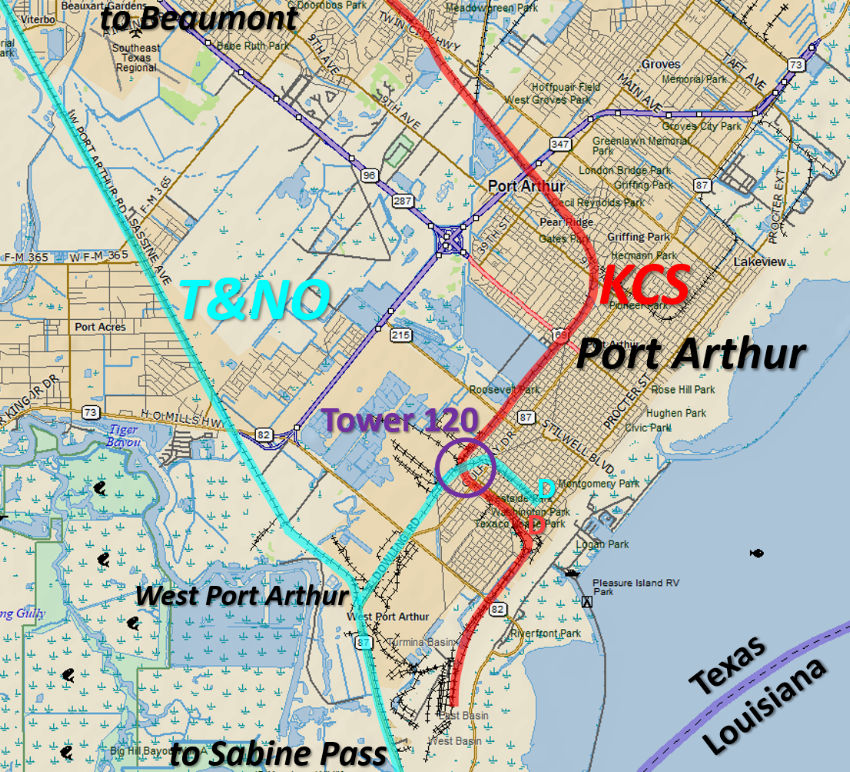

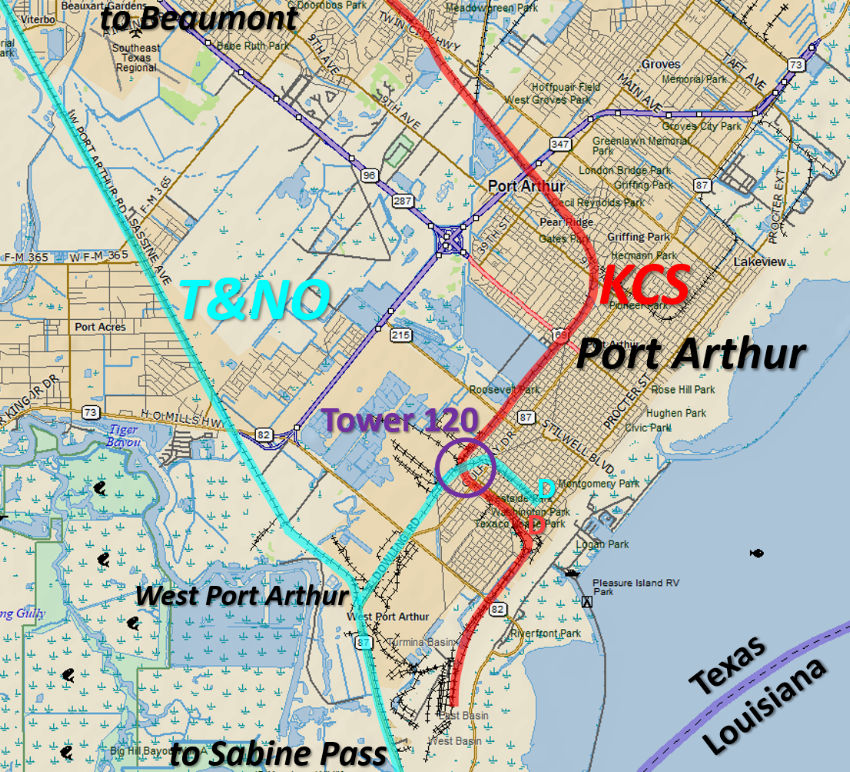

Left:

This south-facing 2008 aerial image (Microsoft Virtual Earth) has been

annotated to show the rail crossing in Port Arthur that was managed by

the Tower 120 interlocker, authorized for operation on September 23,

1925 by the Railroad Commission of Texas (RCT). From its Beaumont -

Sabine Pass line that ran along the west outskirts of Port Arthur, the

T&NO built a 3.4-mile spur in 1908 that went northeast into Port Arthur. It crossed the

T&FS and then turned to a southeast heading (off the left edge of

this image) toward the T&NO passenger depot near downtown, about 1.3

miles beyond the crossing. At the time Tower 120 was commissioned, the T&FS tracks were under

lease to KCS. The KCS passenger

depot was located just over a mile south of the Tower 120 crossing, and

there were tracks near the depot along the Intracoastal Waterway serving

the port facilities.

Below:

This north-facing Google Earth image from 2010 shows a white pole at the

crossing, but the pole does not appear in the image at left.

|

On

December 3, 1892, having built a rail line south from Kansas City to Pittsburg,

Kansas, Arthur Stilwell established a new name for his enterprise; it would be

called the Kansas City, Pittsburg and Gulf (KCP&G) Railway. His plan was to

continue building south to create a direct line to

the Gulf of Mexico as an export outlet

for Midwest grain. Ten days later,

Stilwell acquired a railroad that could be redirected to support his goal, the

Texarkana & Fort Smith (T&FS) Railway. It had been around since 1885 (originally

as the Texarkana & Northern Railway) for the purpose of building a 10-mile line

from Texarkana north to the Red River. The T&FS name had been adopted in 1889 as

the railroad built another ten miles to Ashdown, Arkansas, planning to

continue north to Fort Smith. Stilwell arranged for the Arkansas Construction

Co. to purchase a controlling interest in the T&FS on his behalf. A few months

later, he was successful in getting the Texas Legislature to amend the T&FS

charter to allow for construction south from Texarkana toward the Gulf. Stilwell

elected to use a route through Shreveport, so the T&FS built the Texas portions

while the

remaining tracks were built by a railroad he chartered in

Louisiana.

Stilwell was interested in Sabine Pass, Texas as a potential port on the Gulf, but he also was considering locations on the

Louisiana side of the Sabine River. When

the Houston East & West Texas Railway suddenly came up for sale, Stilwell

strongly considered its purchase. It would provide him with

a completed line from Shreveport to Houston, and he began negotiating

with the railroads in Houston to obtain a route to the Port of Galveston. At the last minute

before the sale went through, Stilwell abandoned the idea, explaining in his

Memoirs that he had "...become possessed of an overpowering fear..."

that using a port directly on the Gulf of Mexico was a mistake due to the

powerful storms that occasionally came through the area. Instead, he

envisioned "...a city of 100,000 persons on the north bank of Lake Sabine

which could be connected with the Gulf by means of a canal about seven miles

long." Stilwell's vision was about five years before Galveston would be

destroyed by the

Great Hurricane

of 1900, still the deadliest natural disaster in U. S. history.

In

his reference tome, A History of the Texas Railroads

(St. Clair Publishing, 1941), the dean of Texas railroad historians S. G. Reed

describes what Stilwell did next...

Within 30 days, he had acquired

40,000 acres on the north bank of Lake Sabine for $7.00 an acre, laid out the

town on 4,000 acres and named it Port Arthur, later sold the remaining 36,000

acres for $40 an acre to Dutch farmers for raising rice, organized the Port

Arthur Ship Canal & Dock Company with a capital stock of $3,000,000, which he

sold in one day and later built a canal seven miles long connecting Sabine Lake

with the Gulf, and built docks and an elevator at deep water on the Lake.

The location of Port Arthur (named for himself, of course) was now known, but

the tracks being built by Stilwell were still well short of reaching it. In 1896, the T&FS

built 24 miles south from Texarkana to the

Louisiana state line, crossing the Texas & Pacific

Railway en route. That same year, the T&FS also built 19 miles of track

between Beaumont and Port Arthur. In between, the Louisiana-chartered railroad built tracks from the Texas border south to Shreveport, continuing farther south to DeQuincy, Louisiana. At DeQuincy, the tracks

turned southwest and reached the Texas border at the Sabine River. In 1897, the

T&FS completed the remaining Texas construction between the Sabine River and Beaumont,

bridging the Neches River near

downtown Beaumont and connecting with the tracks previously built from

Port Arthur. Service between Kansas City and Port Arthur commenced on November

1, 1897.

In

1899, Stilwell lost financial control of the KCP&G and it was acquired in

1900 by the newly chartered Kansas City Southern (KCS) Railway. (Down but not

out, Stilwell moved on to a more ambitious project.) Because KCS was

not headquartered in Texas (it was chartered in Missouri), Texas law

required it to lease, rather than own, the T&FS. In 1933, the State of Texas appealed

an Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) ruling that granted KCS permission to acquire the T&FS, notwithstanding Texas law to the contrary. The

Supreme Court

upheld the ruling in 1934, but the formal merger of the T&FS into the

KCS was delayed until the

lease expired in 1943.

|

The T&FS was the first railroad to serve Port Arthur,

but it was not the first railroad in the area. The Sabine & East Texas

(S&ET) Railway built a line through the wetlands and coastal prairie

between Beaumont and Sabine Pass in 1881, tracks that would eventually

reside in West Port Arthur.

The S&ET was sold to the T&NO in 1882.

The KCS (T&FS) main line was

farther east. It passed through the main part of Port Arthur, making a

sweeping curve to the southwest and then two additional curves to reach

downtown and the port area. Both the T&NO and KCS sought to serve

the rapidly developing facilities with spurs and industrial tracks.

The West Port Arthur area grew as businesses became established

along Sabine Lake and the Port Arthur Canal, and it was the junction for

the T&NO spur to the passenger depot near downtown. The T&NO depot was

less than a half-mile north and slightly east of the T&FS passenger

depot.

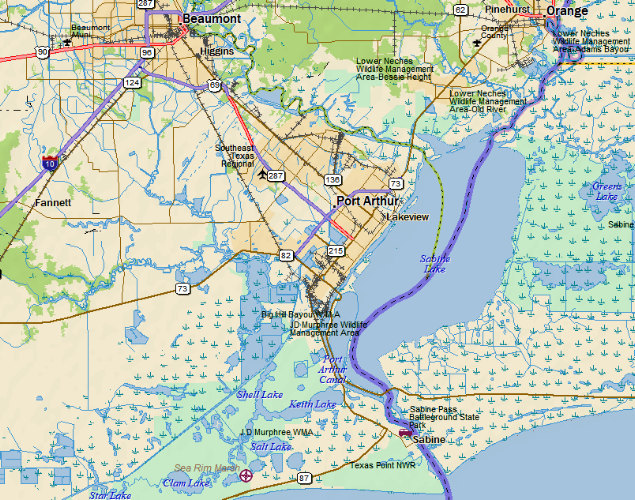

Left: This

annotated Topo USA map shows the KCS and T&NO main lines and the T&NO

spur into Port Arthur. Two miles south of West Port

Arthur, the tracks to Sabine Pass were abandoned in 1932.

Above: vintage

postcard of the T&NO passenger depot in Port Arthur on Austin Ave.

near 6th St. (Texas State Library)

Below: street side of

the T&NO depot, Google Street View, August, 2022; the building does not

appear to be in use

|

While the original intent of Stilwell's enterprise was

to provide a reliable and less expensive outlet for Kansas City grain

commodities, the Spindletop gusher in Beaumont on January 10, 1901 and the

oil field it exposed changed the

local economy forever. The well was 600 ft.

from the T&NO tracks to Sabine Pass and about 1.8 miles from the T&FS main line.

Both railroads stood to gain from the massive industrial activity that would

lead to the modern petrochemical industry that pervades the Beaumont - Port

Arthur - Orange metropolitan area today. The gusher

created a major problem: what to do with the

massive quantity of oil that was suddenly flowing. Storing it, transporting it and

refining it were costly activities requiring large investments. It was for the refining

part of that triad that George A. Burt came to Beaumont...

The George A. Burt Refining

Co. organized in 1901, reorganizing shortly after as the Security Oil Company.

Burt's origins are unclear, with speculation he might have been an agent of John

D. Rockefeller Sr.'s oil giant, Standard Oil. "It's sort of unknown," says Ryan

Smith, executive director of the Texas Energy Museum. "He claimed that he was

not with Standard because with the antimonopoly laws of Texas, Standard was not

allowed to come in. So, it is somewhat speculative as to who he was working for.

It was considered a private endeavor with independent financing." The State of

Texas eventually clamped down, seizing the refinery in 1909 as an illegal

affiliate of Standard Oil and selling it in auction to the Magnolia Petroleum

Co. (Beaumont Enterprise,

September 7, 2008)

The State of Texas had properly discerned that Standard

Oil was behind Burt and Security Oil, leading to the seizure and auction of the

refinery. Col. George A. Burt turns out to have been a New York construction

engineer sent by Standard Oil to build a refinery under his own name, and he had

sold it to Security Oil as it was nearing completion. The Federal antitrust

lawsuit against Standard Oil in 1909 led to its breakup and the seizure of the

Beaumont refinery. Perhaps it is fitting that after a century of mergers and

name changes, the controlling entity in that monopoly, Standard Oil of New

Jersey, now owns the Beaumont refinery under its current name, Exxon Mobil.

|

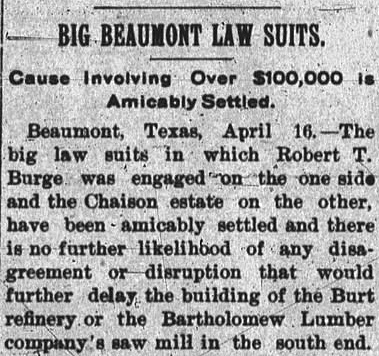

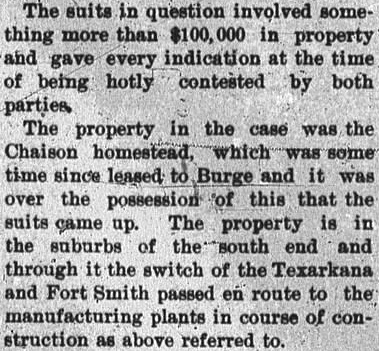

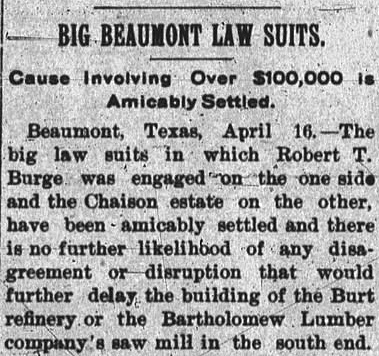

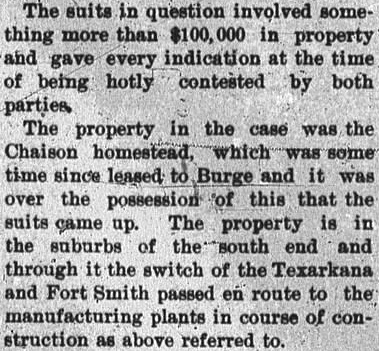

Left and Right: (Orange Daily Tribune,

April 16, 1902) Jean Baptiste Chaison, a French-American soldier in the

Revolutionary War, had settled in Beaumont and died in 1854 (~ 109 years

old, according to legend.) That same year, his son McGuire Chaison acquired land along

the west bank of the Neches River south of Beaumont. McGuire's son,

Jefferson Chaison, became a county judge in

Beaumont in 1890 and led numerous family businesses including the Texas

Rice Land Company, the Chaison Construction Company, and the Jefferson

Chaison Townsite Company.

The family leased their land to Robert

T. Burge, and he proceeded to offer it as a location for the Burt

refinery and a sawmill to be built by the Bartholomew Lumber Co. A

lawsuit over the use of the land was settled amicably and the refinery opened in 1903.

Regarding the land, the article states that "...through it the switch of

the Texarkana and Fort Smith passed en route to the manufacturing plants

in course of construction..." suggesting that by 1902, the T&FS had

already built a spur from their main line onto the Chaison land to assist

in building the plants. By 1911, the refinery was owned by Magnolia

Petroleum, which was acquired in 1925 by Standard Oil of New York, the

company that ultimately became Mobil Oil. |

|

The T&NO built a spur to serve the facilities at

Chaison, but the date of construction has not been determined. It could have

been as early as 1903 but was more likely closer to 1915. The refining company certainly would have favored having

the T&NO as a competitor for the T&FS. To reach the refinery, the T&NO spur had

to cross the T&FS main line. On October 1, 1915, RCT commissioned the Tower 103

interlocker for operation at this crossing. In a list published thirty days

later, RCT described

it as a 10-function plant located at "Chaison" with a "Character of Machine" of

type "Mechanical". The "Mechanical" description remained unchanged until the end

of 1927 when RCT's published list changed Tower 103's "Character of Machine" to

"M.-Cabin", indicating it was a cabin interlocker with a mechanical plant.

Cabin interlockers were employed where a low-traffic line (here, the T&NO spur)

crossed a busy line (here, the T&FS main track.) They were cost-effective

because they were unmanned, hence there was no labor expense for

operating the interlocker. Instead, it would be operated by a crewmember from trains on the lightly used line that wanted to cross the busy line.

The train would stop short of the home signal at the diamond and a crewmember would disembark

and enter the cabin. He would move the levers as necessary to clear the derails and present

a PROCEED signal for his train while engaging the derails and presenting a STOP

signal on the busy line. After his train crossed the diamond, the crewmember

would reset the levers to allow unrestricted movements to resume on the busier line.

Thus, as he returned to his train and departed, the signals were left as they had been when

the train had arrived at the diamond.

The ten functions of the Tower

103 interlocker were probably a home signal and a derail in each of the

four directions, plus a distant signal in both directions on the KCS track. The

T&NO track did not need distant signals because as a spur, its trains were

always operating at low speed and they would plan to stop at the crossing until

the home signal near the diamond was visibly indicating PROCEED. If the tower was manned

in its early years, the

PROCEED indication would be set by the operator when he detected the approaching

train, assuming the KCS line was clear. As an unmanned cabin interlocker (at

least by the end of 1927 if not earlier), the PROCEED indication could only be

granted by a crewmember from a T&NO train entering the cabin to move the levers.

Did the

revision of the "Character of

Machine" to "M.-Cabin" at the end of 1927 indicate an actual change to

the operation of Tower 103? Or was it merely a documentary change so that RCT's

annual published list of active interlockers could distinguish between manned

and unmanned towers? The first RCT list of active interlockers that gave

any indication of the existence of an unmanned cabin interlocker was the one published December 31, 1923

where Tower 111 and Tower

113 were both listed as "Mech.-Cabin". That was Tower 113's first appearance

in RCT's annual publication, but Tower 111 had been commissioned on November 13, 1919

and had first appeared in the table published the following month, identified as a "Mechanical"

interlocker. Like Tower 103, it is not known

whether Tower 111 was initially manned and then converted to an unmanned cabin,

or whether this was simply a documentary change to reflect its on-going status as a cabin

interlocker. At the very least, the list published at the end of 1923 proves that by that

date, RCT had a way of identifying cabin interlockers in its table. It chose not to do so for Tower 103 for four more years.

|

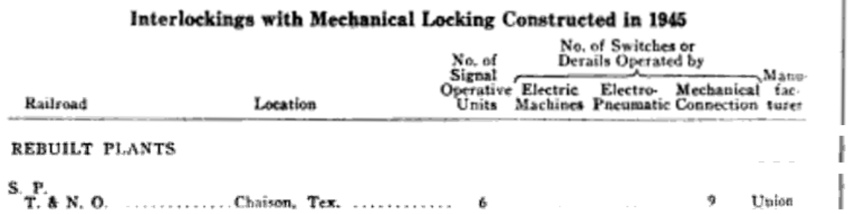

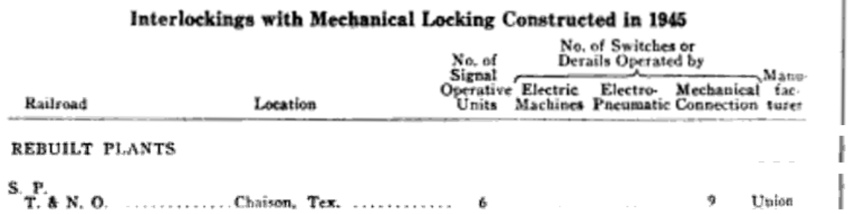

Left: Under

the title "Interlockings with Mechanical Locking Constructed in 1945"

and a subheading of "Rebuilt Plants", the January 5, 1946 issue of

Railway Age has a table

that lists Chaison as having six "Signal Operative Units" and nine

"Switches or Derails Operated by Mechanical Connection" using a plant

manufactured by Union Switch & Signal Co. This entry documents a new or

rebuilt interlocker to replace the plant that had been operating at

Tower 103 for thirty years. How these signal and function numbers map to

the original design is undetermined. |

Richard Day's 1964 photo of the Tower 103 cabin shows a building with

multiple windows: one on the back wall to the left of the door, one visible

through the door on the far wall, and what might have been two windows in the

door. The front wall cannot be seen in the photo, but given all of the other

windows, surely there had to be one facing the KCS tracks. This many windows is unexpected for a cabin hypothetically built to be

rarely occupied, and only briefly at those times. The cabin certainly looks

like it was intended to be occupied for lengthier periods (in contrast, for

example, to the cabin interlocker at Tuscola.) The nature of the cabin's design with

multiple windows and the fact that it was not listed as a cabin until four years

after such status began to be incorporated into RCT's list

suggests that it was initially a single-story manned tower that was converted to

an unmanned cabin in 1927. It should also be noted that the control stand

mounted trackside merely reflects the much later transition to

pushbutton-controlled electronic relays with timeout circuits as the preferred

approach for manual interlocker controls. Mounting the lockable control stand

outside allowed the cabin -- and its maintenance needs -- to be eliminated.

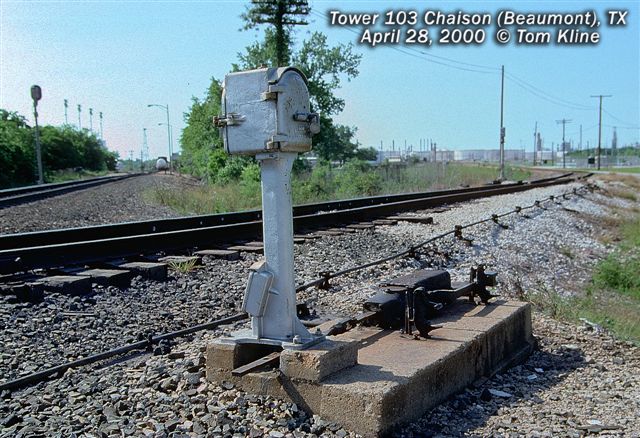

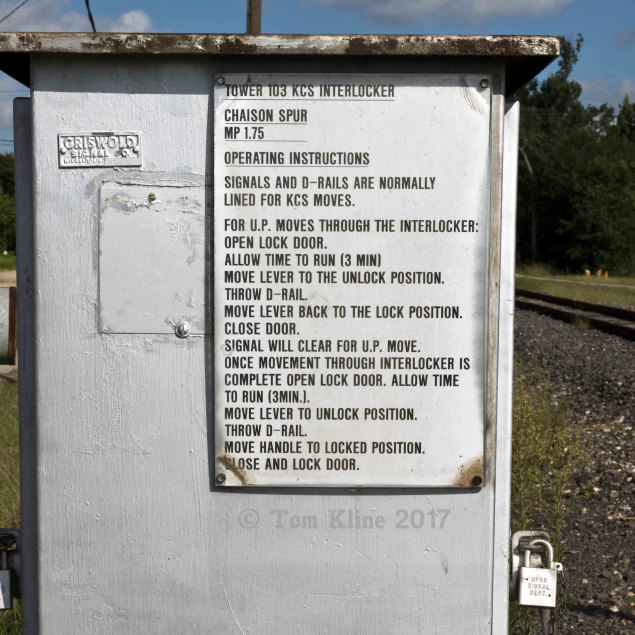

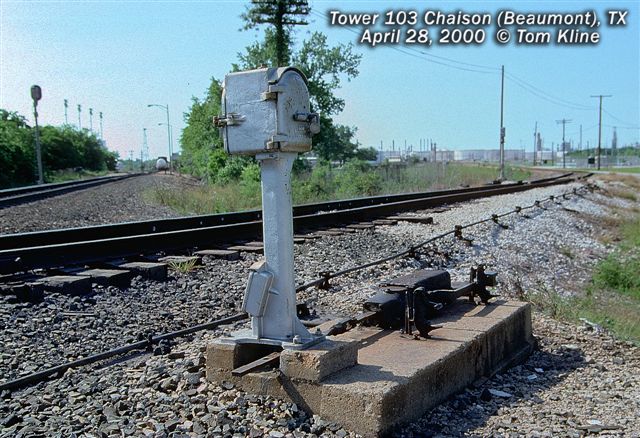

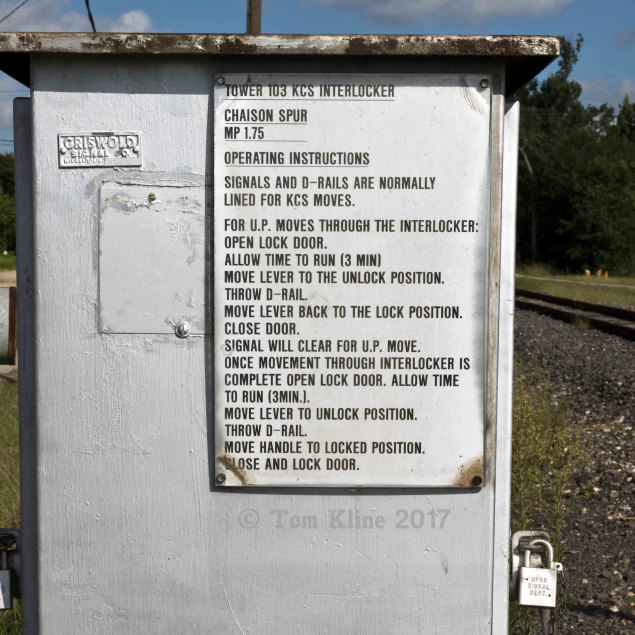

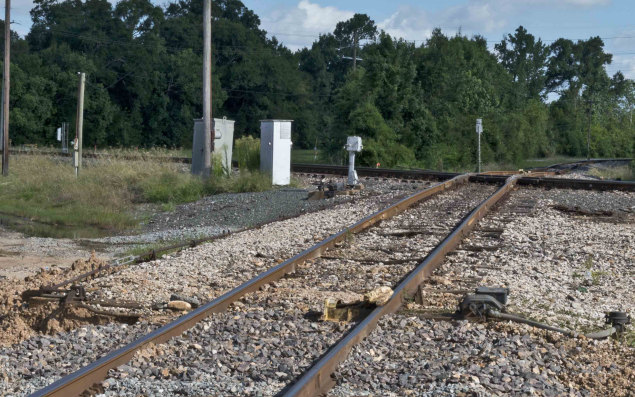

Above Left: Tom Kline took

both of these photos at the Tower 103 interlocker in April, 2000. Tom writes

"The view of the interlocker electric lock and rod operated derail is looking

northeast. The track to the left is the KCS and you can see the light towers for

Lamar University's stadium that are up against the tracks." Compare Tom's view

looking northeast with Richard Day's 1964 view to the

southwest showing the control stand from the opposite

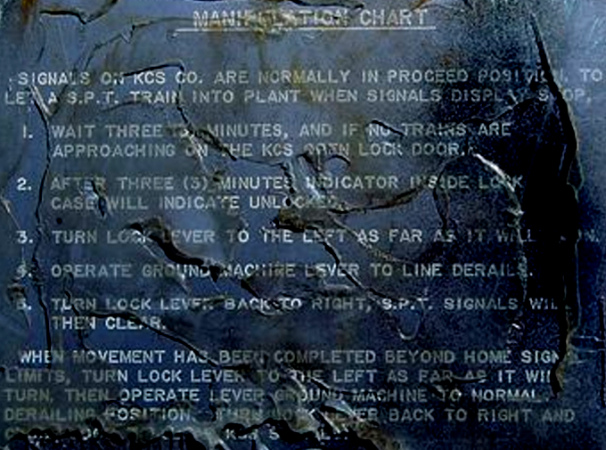

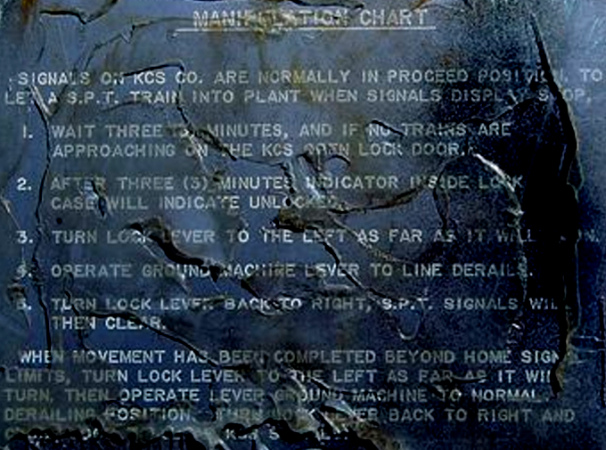

side. Historic aerial imagery indicates that the cabin had been removed by 1970. Above Right: Tom notes

that the interlocker instruction plate is on a relay case near the control

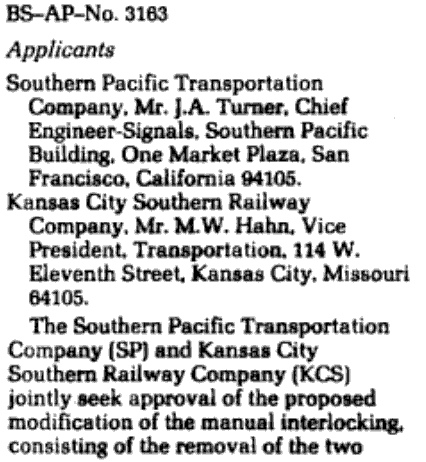

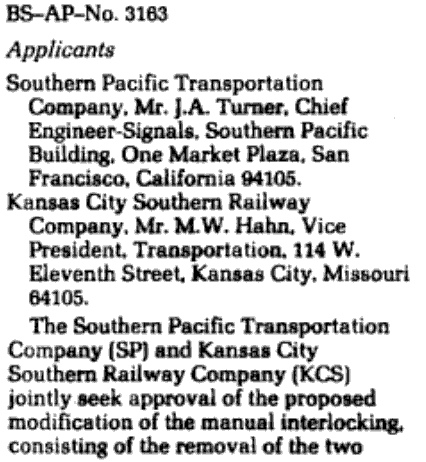

stand. Below Left: The

Federal Register of May 1, 1992 contained

this notice that SP and KCS had jointly applied to the ICC for approval to

remove "two electrically locked pipe-connected derails near Chaison, Texas..."

The derails were on SP's tracks, and were simply "worn out" (but if

they served a valuable purpose, why not replace them?) As Tom's photo

above shows, a pipe-connected derail on the former SP track was in place in

April, 2000, protecting against loose railcars escaping from the refinery and

rolling across the KCS main line. Perhaps only partial approval was granted. A

derail on SP's tracks west of the KCS main served little purpose; there was no yard

in that direction, hence, no protection needed for escaping railcars. And SP

trains were always moving slowly since they had to stop at the crossing anyway,

and thus were not likely to overrun the diamond.

Below

Right: This Google Street View image from June, 2022 shows that

everything visible in Tom's photo, including the pipe-connected derail, is still

in place.

|

Left:

The T&NO line from Beaumont to Port Arthur, now owned by Union Pacific (UP), is about two miles west of the refinery. The T&NO built a spur that

entered the facility from the south,

crossing the T&FS main line at Tower 103. The T&FS tracks were already leased

and operated by KCS when the refinery was built, and KCS continues providing

service today. Both main lines proceed into Beaumont off the left edge of the

image, and both continue to Port Arthur off the bottom of the image. The precise

track ownership within the refinery and its surroundings is undetermined, and

some (or all) of the trackage might be owned by Exxon Mobil.

Below: At Sabine Lake, the

Neches and Sabine Rivers merge, and the natural outlet through Sabine

Pass on the Gulf was too shallow for ocean-going vessels to reach inland

ports. Stilwell understood this and had provided financial backing to

complete a seven-mile deep water canal between Port Arthur and Sabine

Pass in 1899. To facilitate shipping into Beaumont, Congress

appropriated funds to dredge the Neches River, creating a 25-foot deep

channel from Sabine Lake by 1916. It has since been deepened and

widened, and the Sabine River has been

dredged to Orange creating another inland harbor.

|

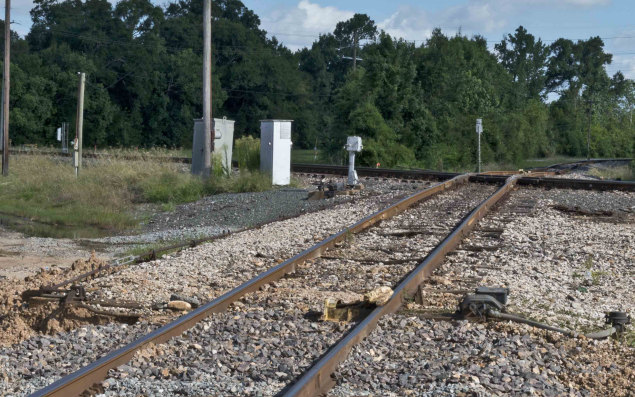

Above Left: In 2017, Tom Kline

took this photo of the revised interlocker operating instructions posted at

Tower 103. Above Right: Mark

St. Aubin captured this February, 2023 image of the mechanical derail system at

Tower 103 looking northeast toward the refinery.

Below Left: This photo looks south across the diamond,

with the KCS rails to the left and the UP rails to the right. Note that UP's

track has been straightened since the 1964 photo at top of page, and that a

short staff light signal is still in use. (Tom Kline, 2017)

Below Right: This close-up

shows the derail engaged on UP's track. It prevents a rail car from escaping

uncontrolled from the refinery and crossing the KCS main line. (Tom Kline, 2017)

|

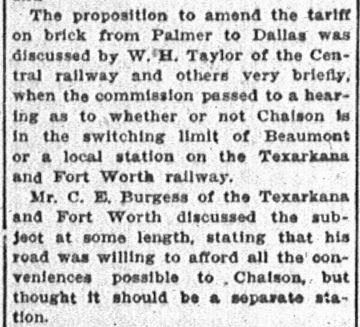

The activity at

Chaison motivated T&FS to build a yard and station. Controversy ensued as to whether the Chaison station was within the T&FS switching

limits for Beaumont. Because RCT issued tariffs for commodities shipped

by rail between specific points within Texas, tariffs to or from Beaumont would apply to any location within the T&FS switching limits

for Beaumont. Did they also apply to shipments in and out of Chaison, a

couple of miles from downtown Beaumont?

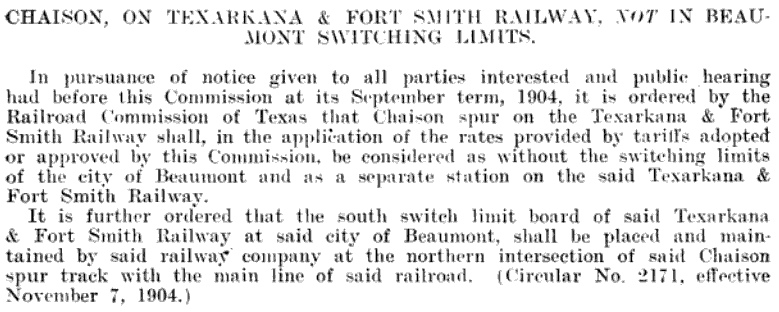

Left:

Austin Statesman, September 21,

1904

Right: RCT

1905 Annual Report |

|

Jimmy

Barlow provided the following additional discussion about Chaison on August 14, 2005:

"When I was in Beaumont last weekend, I took time to

check out the Tower 103 interlocker. This is where UP's Chaison Spur business

track crosses the KCS main line immediately south of KCS's Chaison Yard. The

spur breaks off UP's Sabine Industrial Lead (old SP/T&NO Pt. Arthur branch) half

a mile north of Guffey, serves a concrete plant on the east side of US-69, and

after crossing the KCS serves the petrochemical area dominated by the Mobil

refinery (now Exxon Mobil). The crossing itself is kind of interesting, with the

UP track having a short but steep ascent to the KCS from either side. Even so,

there are derails on the UP maybe 50 yards on each side of the diamond. These

are controlled by a single CTC-style switch motor to which they're connected via

the same type of rod system found at manual interlocking towers! UP's absolute

signals are a dinky little 2-aspect style on medium-height poles, and the rails

are very shiny. Indeed, KCS personnel at Chaison estimated that UP crosses there

at least 5 days a week. This spot is easy to photograph, with access via Olin Rd

off MLK, less than half a mile north of MLK's intersection with US-69 in

south-east Beaumont. Local "railspert" Gary Williams says that both T&NO and KCS

had depots at Chaison years ago. If I recall correctly...the current KCS yard

office was built as a passenger station (to replace their old downtown

station--on KCS Street!--when they vacated that facility in the mid '60's), but

I have a feeling Gary was talking about an earlier KCS depot. He also says that

long-gone old-timers used to say that T&NO once ran a "mixed" train to Chaison

from downtown Beaumont! I wonder if it appears in any old timetables? (Note:

This area is called Zummo on some maps; don't know if that was ever a rail name

or not.) Interestingly, the first street south of Olin Rd and on the same side

of MLK is labeled "V W and R Dr." I got all excited when I saw that street sign,

hoping those were the initials of some old railroad, although I couldn't think

of any rail line so named (and subsequent research has turned up none). Sure

enough, a brother-in-law who lives in that area tells me they stand for Van

Waters & Rogers, a former chemical distributor (now known as Univar) who at one

time owned a warehouse on the one-block-long dead-end street. He said the

warehouse now belongs to healthcare products provider McKesson--which could

explain why MapQuest shows that street to be McKesson Dr."

A situation similar to Chaison existed in Port Arthur;

a T&NO spur

crossed the T&FS main line. The spur was built from the Sabine Pass line at West

Port Arthur into downtown Port Arthur in 1908, primarily to reach the passenger

depot although the T&NO did serve businesses along the way. The spur's crossing

of the

T&FS main line remained uncontrolled for seventeen years. By

law, all trains were required to stop before passing over an uncontrolled

diamond even though RCT regulations also required uncontrolled crossings to be

gated.

|

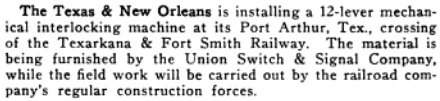

Left:

As reported in Railway Signaling &

Communications, July, 1925, the T&NO took the lead on

building and installing the Tower 120 interlocker, a 12-lever mechanical

plant. RCT commissioned it in the fall of 1925. At the end of 1925, RCT

reported the commissioning date as September 25, 1925. A year later, the

commissioning date changed to December 23, 1925. At the end of 1927, it changed again

to September 28, 1925, and that date stuck through the

final comprehensive interlocker list published by RCT on December 31,

1930. |

RCT's documentation showed Tower 120 having eleven

functions, and this number never changed through the final interlocker list

published at the end of 1930. What did change

(besides the aforementioned commissioning date) was the

"Character of Machine". The list published at the end of 1925 showed

Tower 120 as "Mechanical". This implies that it was a manned tower, not a cabin

interlocker, because there were cabin interlockers identified in the list,

specifically Towers 111, 113, 122

and 123 listed as "Mech.-Cabin". Furthermore, RCT kept files on each interlocker during the design,

construction, and commissioning phases, and maintained them long term as modifications

to the interlocking plant were incorporated over the years. If Tower 120 had been planned as a cabin

interlocker, RCT would have had no reason to identify it as "Mechanical" instead of "Mech-Cabin"

in the lists published at the end of 1925 and 1926.

| RCT's list of December 31, 1927

changed Tower 120's type to "M.-Cabin". It's a reasonable

conjecture that

its implementation followed the same script as Tower 103, i.e. a single-story manned structure

subsequently converted to an unmanned cabin interlocker. In particular,

it does not

seem coincidental that, despite being commissioned ten

years apart, Tower 103 and Tower 120 both became listed as type

"M.-Cabin" at the same time.

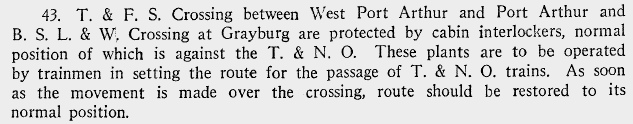

Right: SP's T&NO Employee Timetable for the

Beaumont Division dated September 7, 1930 had Rule 43 for operating

the cabin interlockers at Port Arthur and

Grayburg. Chaison was omitted, perhaps because the timetable only

detailed main lines and subdivisions, and did not include the Chaison

spur. |

|

Evidence of the specific allocation of the functions of the Tower 120 interlocker

has not been found. An educated guess is that the eleven functions consisted of a home signal, a distant signal and a derail in each of the four

directions, except that the distant signal was omitted for T&NO trains coming out of downtown. The crossing was just over a mile

from the depot, so trains would have been accelerating slowly out of downtown

and they would anticipate the need to stop at the home signal before crossing

the diamond. If this function allocation is correct, it reinforces the idea that

the tower was originally manned. A distant signal for T&NO eastbound trains

(toward downtown) would never have been needed if the tower had always been an

unmanned cabin interlocker. Rule 43 required every

T&NO train to stop so that a crewmember could enter the cabin to operate the

controls. There would be no need for a distant signal to guide the behavior of

eastbound trains approaching the crossing; by rule,

all of them had to stop at the home signal anyway.

The T&NO spur was abandoned from the Tower 120 crossing into downtown in the

late 1990s. The crossing is no longer in service, but the remainder of the spur

is intact from West Port Arthur so that UP can serve the Valero and Motiva

refineries.

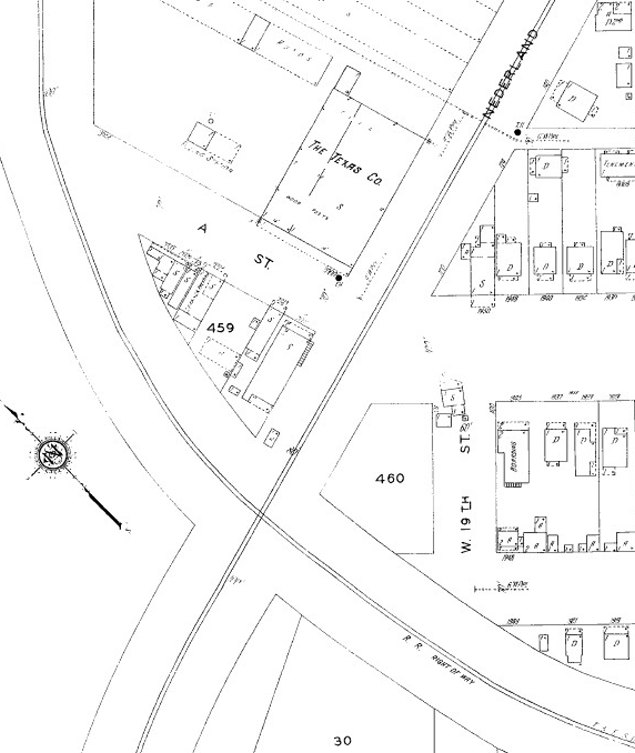

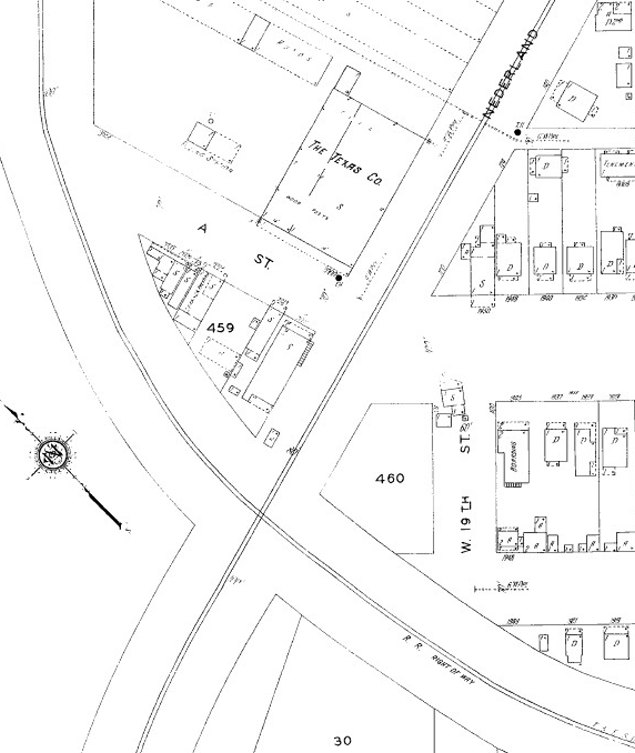

Above:

This 1930 Sanborn Fire Insurance map shows the Tower 120 crossing, with the

T&FS running from upper left to lower right, and the T&NO from lower

left to top center. The small, 1-story rectangular building due north

of the diamond within the railroad right-of-way is probably the Tower 120 cabin.

Unfortunately, the crossing is

not included in the prior 1923 map set, so whether the structure

existed prior to the commissioning of Tower 120 cannot be checked. It does not appear on

the next earlier map set from 1918. |

Top:

This Google Street View from December, 2021 looks west-southwest from

Houston Ave. along the T&NO right-of-way toward the former Tower 120

crossing and where there are now two KCS tracks.

Bottom: In the

opposite direction, T&NO rails remain buried under Houston Ave. and

protrude onto the dirt on the east side of the roadway. The tracks went

straight for another quarter mile and then made a 60-degree curve to the

southeast and continued another three-quarters of a mile to reach the

passenger depot. |

Below: This Google Earth image from November, 2022 shows

that KCS has laid an additional track through the former Tower 120 crossing.

Compare this image with the 2010 view at the top of the page. Historic aerial

imagery shows that the track construction was well underway by November, 2011.

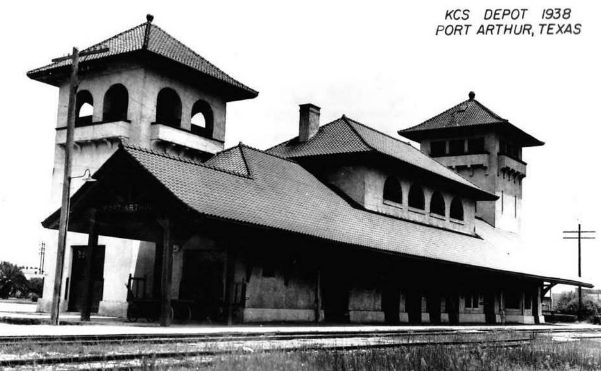

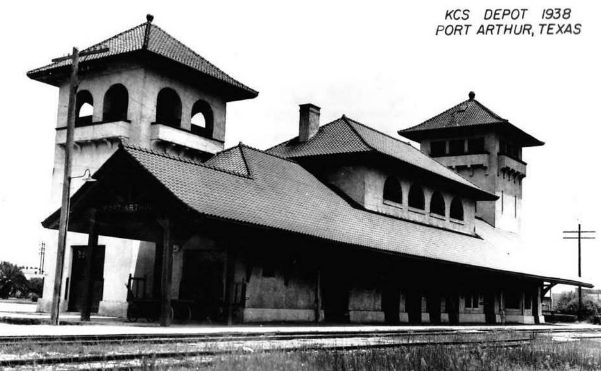

Above Left: undated photo,

T&NO depot in Port Arthur (Portal to Texas History)

Above Right: 1938 photo of the KCS depot in Port Arthur

(H. D. Connor collection) The KCS depot was razed in 1969.

Below Left: A replica KCS

depot was built at the same site in the 2000s and now hosts Port Arthur's

International Seafarer's Center. (Anderson England photo)

Below Right: KCS 29 at the

depot in 1966 (Fred M. Springer, Center for Railroad Photography and Art, hat

tip Chino Chapa)