((c) chillicothetx.com)

Texas Railroad History - Tower 83 - Chillicothe

((c) chillicothetx.com)

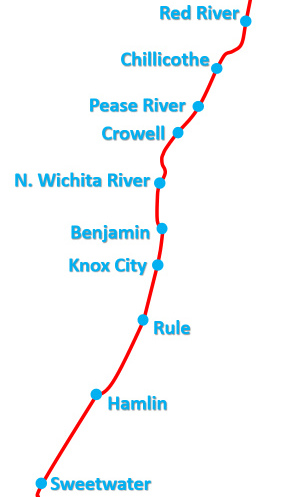

A Crossing of the Kansas City, Mexico & Orient Railway and the Fort Worth & Denver City Railway

Left:

Facing south along the former Kansas City, Mexico & Orient rail line at

Chillicothe, the tracks had already been removed near the Tower 83 crossing when

this photo was taken c.1996. The Fort Worth & Denver tracks are barely visible

passing perpendicular to the KCM&O right-of-way on this side of the white

equipment cabinet and the tan interlocker cabinet.

(Jim King photo) Below: This

closer view shows a new equipment cabinet in place, and the abandoned Santa Fe depot at Chillicothe

more easily visible in the distance.

(Google Street View 2013)

Left:

Facing south along the former Kansas City, Mexico & Orient rail line at

Chillicothe, the tracks had already been removed near the Tower 83 crossing when

this photo was taken c.1996. The Fort Worth & Denver tracks are barely visible

passing perpendicular to the KCM&O right-of-way on this side of the white

equipment cabinet and the tan interlocker cabinet.

(Jim King photo) Below: This

closer view shows a new equipment cabinet in place, and the abandoned Santa Fe depot at Chillicothe

more easily visible in the distance.

(Google Street View 2013)

Chillicothe was settled in the early 1880s, reportedly

named for the Missouri hometown of A. E. Jones, one of the landowners in the area. It was

only

a tiny community when local citizens filed for a post office in 1883; the

application stated "seventy-five" as the population to be served.

Thus, when the Fort Worth & Denver City (FW&DC) Railway built through

Chillicothe in the mid 1880s, there was not yet a town newspaper to report the

celebration, if the locals even bothered to have one. The FW&DC had begun laying rails in 1882 when it built tracks from Fort

Worth to Wichita Falls. After a three year delay, records of the Railroad Commission of Texas (RCT)

show that the extension

northwest from Wichita Falls reached Harrold, 34 miles away, by the end of 1885.

Construction resumed on May 24, 1886, according to the next day's issue of

the Galveston Daily News. Thirty miles west of

Harrold, rails being laid

through Chillicothe wasn't particularly newsworthy, although the

Fort Worth Daily Gazette of January 29, 1887

did issue a belated one-sentence pronouncement: "Chillicothe is the name of

the first railroad town in Hardeman County." The FW&DC continued

its rapid northwest progress, reaching the New Mexico border

in 1888 at the new town of Texline where it connected to rails

coming south from Denver. Only sixteen months after building through

Chillicothe, trains began running the entire distance between Denver and Fort Worth in

April, 1888.

Twenty years later, a second railroad

built through Chillicothe. It was the realization of Arthur Stilwell's

imaginative proposition to construct a direct line from Kansas City to Topolobampo, Mexico on the Gulf of

California, the nearest Pacific port to Kansas City. Called the Kansas City,

Mexico & Orient (KCM&O) Railway, it was

the second major railroad Stilwell had started. He had used a similar approach in building the

Kansas City, Pittsburg & Gulf (KCP&G) Railway due south from

Kansas City on the shortest route to the Gulf of Mexico, where he founded his namesake town,

Port Arthur. Unfortunately for Stilwell, he was

booted off the KCP&G management team during a brief bankruptcy while the

railroad was being reorganized into today's Kansas City Southern (KCS) Railway.

Unhappy about losing his railroad, the KCP&G, Stilwell's mood brightened

soon thereafter when his friends hosted a special dinner in his honor on

February 10, 1900. For Stilwell, it was the perfect time to

reveal his newest railroad idea to his audience of friends (and potential

investors!) He no doubt explained that the KCM&O route

was ostensibly 400 miles closer than shipping by rail from Kansas City to

California ports. He may not have mentioned that actually achieving the shorter distance

would require building across Copper Canyon

in Mexico, where the terrain would present technical issues that would

undoubtedly slow construction. Within a couple of months, Stilwell was in Mexico

where President Porfirio Diaz was very supportive of the plan and agreed to have

the Mexican government subsidize the KCM&O tracks in Mexico at $5,000 per mile.

Since there would never be enough

resources to build the entire line quickly all at once, there needed to be

some plan for interim operation to create income as sectional progress was made.

But operating a railroad costs money -- staffing, locomotives, railcars, depots, fuel, etc. -- and the KCM&O's entire route was mostly

through sparsely populated areas where local commerce would likely be

insufficient to sustain profits for the entire enterprise. These facts

incentivized Stilwell to buy land and found as many towns as possible along the

route since the sale of town lots would produce an additional revenue stream.

Stilwell also needed to have flexibility in route selection so he could seek

bonuses from existing towns and counties where appropriate, so long as the final

route remained true to the railroad's objective of having a short line to the

Pacific from the Midwest.

|

Examining potential ways to cross Texas

from Oklahoma to Mexico,

Stilwell discovered seven miles of track running south from

Sweetwater toward San

Angelo, two towns he was considering for the KCM&O route. He was able to acquire

the railroad and have its charter expanded to permit construction from

Sweetwater north to the

Red River and from San Angelo south to the border at Presidio. The

revised charter also changed the name to the KCM&O of Texas, a

subsidiary of his parent company. Stilwell built north from Sweetwater toward the Red River,

with the rails reaching

Knox City in 1906 and Benjamin in 1907. The tracks coming south from Kansas

would cross a new Red River bridge into Texas, but directly south of the Red, the

precise route was a well-kept secret. It would need to

cross the FW&DC somewhere in Hardeman County, and both

Quanah, the county seat, and Chillicothe

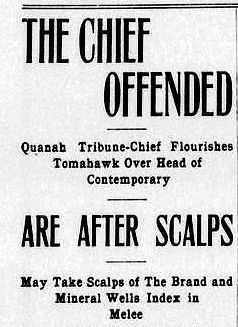

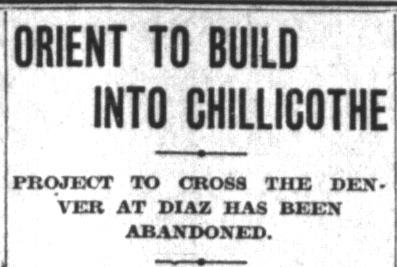

were potential options. Left: The Hereford Brand of May 15, 1908 published a lengthy article defending stories it and the Mineral Wells Index had published about the fight between Quanah and Chillicothe over which town would get the KCM&O. The attacks were coming from the Editor of the Quanah Tribune-Chief who accused the Brand of "making ridiculous statements." As it turned out, the Brand was correct when it claimed that Chillicothe had won out, though at the time, the KCM&O had not yet given up their primary option of crossing at a new town. Right: The Fort Worth Record and Register of July 4, 1908 announced the big news that the KCM&O was abandoning its plan to found the new town of Diaz for the FW&DC crossing and would instead cross at Chillicothe. |

|

|

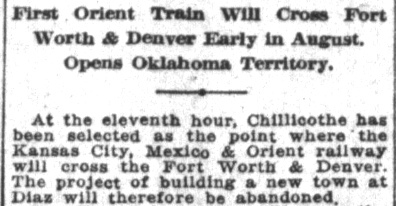

Stilwell's plan all along had been to cross the FW&DC at a new town he would plant between Chillicothe and Quanah to be named for President Porfirio Diaz. To this end, Stilwell had obtained a special rate in 1903 for construction materials shipped on the FW&DC to Chillicothe and Diaz, a common industry practice (left, RCT 1907 Annual Report.) Materials would be delivered to Chillicothe until facilities could be built at Diaz. The expectation was that selling town lots at the crossing of two major railroads would yield a revenue bonanza. The planned location of Diaz has not been determined nor has the reason for Stilwell's failure to develop it. |

The Fort Worth Record and Register of September

21, 1908 reported that the KCM&O tracks from the north had entered Chillicothe

two days earlier and that a connection to the FW&DC would be built

immediately. The

Aspermont Star of November 5, 1908 reported

that southward construction had reached a point seven miles north of the Pease River.

The Pease River bridge was already in progress, and the rails from the north and

south would ultimately join there in early 1909. On January 31, 1909, the

Abilene Reporter published a passenger schedule

effective that day that had a northbound train to Wichita, Kansas from

Sweetwater departing at 10:00 am, and a southbound train from Wichita arriving into

Sweetwater that same evening at 9:00 pm.

Work on the line south from Sweetwater

began a couple of months later and reached San Angelo in September, 1909. In

1910, construction was initiated southwest from San Angelo, but by the time

tracks reached Fort Stockton in November, 1912, the KCM&O had entered

receivership. The Receiver authorized funding for completion of the line into

Alpine hoping that the connection there with Southern Pacific (SP) would

stimulate traffic and revenue. Alpine was reached in 1913 and the receivership

ended in 1914, but the SP connection ultimately did little to stimulate traffic.

The KCM&O went back into receivership in 1917.

The receivership of

1917 would last ten years. Even when the bankruptcy judge forced a sale of the

KCM&O in

1924 (to payoff a $3 million U. S. Government debt), the buyer was the

Receiver's General Counsel who was also a Trustee for one of the creditor

groups. The railroad continued the reorganization of its finances, and

ultimately, the KCM&O spent the vast majority of its years

operating under the direction of the Bankruptcy Court. This was simply the

manifestation of insufficient commerce along the line due to the lack of

population. The projected advantage of shipping through Topolobampo could not be

realized until the track segment across Copper Canyon was complete.

Unfortunately, this would not occur until 1961, long after the Panama Canal had

opened in 1914 to alter the economics of global shipping.

In the end, the

KCM&O was sold to the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway, a transaction

approved by the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) on August 28, 1928. Santa

Fe also bought the Mexican counterpart, the KCM&O of Mexico, but sold it soon

thereafter. The KCM&O's operations were integrated with

other Santa Fe components and a 72-mile line to the border at Presidio was built

departing SP's Sunset Route tracks at Paisano Pass (west of Alpine, reached via

trackage rights on SP.) The first train arrived at Presidio on November 2, 1930.

Using the new bridge over the Rio Grande, the train proceeded on a

goodwill tour into Mexico from Ojinaga to Chihuahua.

In December, 1908, a

month prior to KCM&O service beginning between Wichita and Sweetwater, the FW&DC

had come under the ownership of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad, a

large system that operated throughout the Midwest and across the northwestern U.

S. Thus, Santa Fe's acquisition of the KCM&O twenty years later made Chillicothe

the junction town of two of the biggest railroads in the country. Despite the bonanza of being served by through lines of two major railroads, Chillicothe's

population peaked at about 1,600 in 1930 and has declined significantly since

then. Santa Fe somehow managed to keep the KCM&O route through Chillicothe

operational for several decades before finally selling the tracks between Maryneal (seventeen miles south of

Sweetwater) and Cherokee, Oklahoma (seventeen miles south of the Kansas border)

in 1991. The buyer was a short line railroad, the Texas &

Oklahoma (T&O) Railroad. Within Texas, the T&O abandoned the segment from Sweetwater

to the Red River in 1995. The tracks from Sweetwater to Maryneal were retained,

and they remain intact today to serve a large cement plant.

|

Recent Views Along the Kansas City, Mexico & Orient Right-of-Way Red River bridge: when the line was scrapped, the half-mile long bridge over the main Red River and the Salt Fork was left in place (Google Earth, May, 2022) Chillicothe: abandoned Santa Fe depot, November, 2008 (John Strenski photo); it was still standing as of May, 2022 (Google images) Pease River bridge: like the Red River bridge, the Pease bridge was left intact when the line was scrapped (Google Earth, August, 2019) Crowell: looking south from US Hwy 70, the scrappers left a relay cabinet behind (Google Street View, April, 2022) North Wichita River bridge: looking west from Texas Hwy 6, concrete abutments and various timbers remain (Google Street View, April, 2022) Benjamin: looking south from US Hwy 82 (Google Street View, April, 2022) Knox City: bridge supports in the Brazos River, six miles north of Knox City (Google Street View, April, 2022) Rule: The Rule depot was saved and currently sits near the intersection of 5th St. and Pawnee. (Google Street View, June, 2022, hat tip Jim Korman) Hamlin: ...was the site of the non-interlocked crossing of the KCM&O (blue, 1906) and the Texas Central (red, 1907), which shortly thereafter became a property of the Missouri, Kansas & Texas Railway. There was an exchange track on the north side of the diamond. (Google Earth, 2021) Sweetwater: The ornate KCM&O passenger depot sat in this vacant spot facing trackside to the left. The Santa Fe track to the right led to the Texas & Pacific tracks downtown, but now rejoins the former KCM&O grade to go south to Maryneal. (Google Street View, February, 2013) |

|

Left:

This annotated 1956 aerial image ((c) historicaerials.com) highlights

the crossing diamond (red circle) at Chillicothe and other nearby items. RCT commissioned

Tower 83 as a 20-function mechanical

interlocker in 1910 to control this crossing.

Twenty functions (eight more than the basic minimum) likely confirms the

presence of one or more connecting tracks as mentioned in the

Fort Worth Record and Register

article previously cited. There were two such tracks

(orange arrows) in the western quadrants at least by 1953 that probably

date back to the early days. The KCM&O tracks (pink arrows) ran

generally north / south while the tracks (yellow arrows) of the FW&D

(the "C" had been dropped in 1951) ran generally east / west (and still

do!) As of 1956, the crossing had been managed by an automatic

interlocker for more than twenty years. The FW&D passenger station

(green rectangle) was east of the crossing and is no longer standing

while the Santa Fe (ex-KCM&O) depot (blue rectangle) south of the

crossing still stands. Below: FW&D Depot, Chillicothe, 1971 (H. D. Connor collection)  |

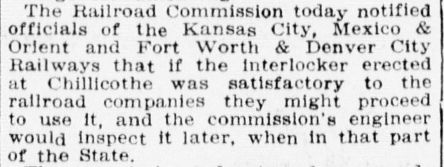

| Right: The San Antonio Daily Express of July 15, 1910 reported the railroads had been notified that they could use the Tower 83 interlocker as soon as it was installed without waiting for RCT inspection. RCT's annual table of active interlockers dated October 31, 1910 listed Tower 83's commissioning date as March 18, 1910, four months prior to this news item. The 1916 list corrected the date to be July 14, 1910, i.e. the railroads began using the interlocker the day they received the notification (although the news item says "today notified", it was probably published the following day.) The commissioning date remained unchanged through the final list published by RCT at the end of 1930. Three different values were reported for the function count of the Tower 83 plant: 29 (1916-1925), 13 (1927-1928), and 20 for all other years 1910-1930. |  |

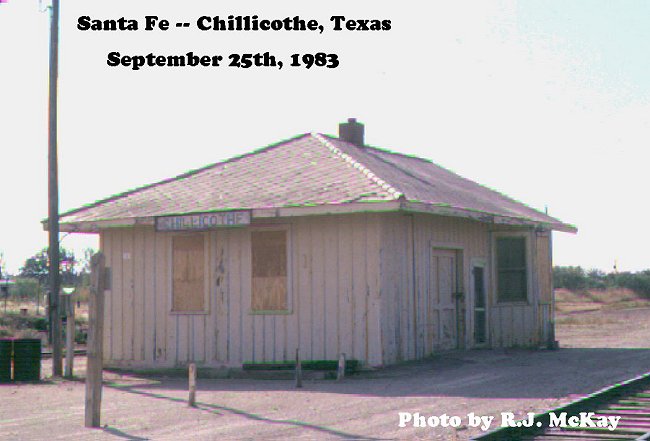

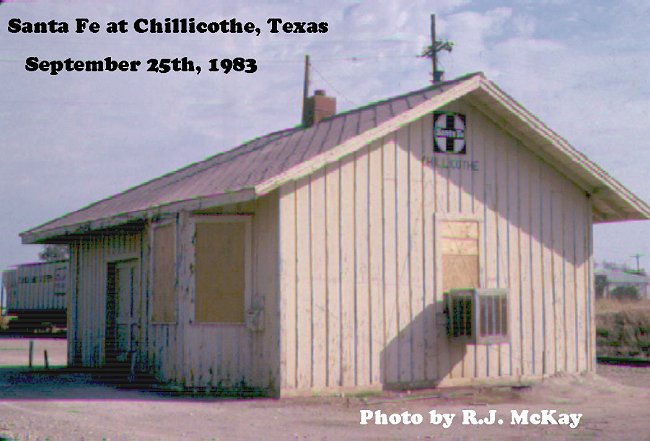

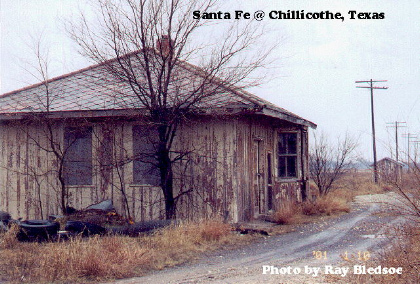

Below: The 1956 view of the Santa Fe depot at Chillicothe

in the blue rectangle above shows it to be roughly twice as long as these ground level shots taken in 1983 (left and

center, R. J. McKay) and 2001 (right, Ray

Bledsoe.) This is because in 1959, Santa Fe substantially shortened the

Chillicothe depot, a practice they repeated at other KCM&O depots along the

line. The result was that the south end of the depot (center photo) no longer

had a hip roof, while the north end of the depot (left and

right photos)

retained its hip roof (hat tip, Evan Werkema.)

The available evidence suggests that Tower 83 was

originally a manned tower. With exchange tracks to manage, it was almost

assuredly a typical two-story structure, but thus far, no photos of it have been

located. In a table of active interlockers published by RCT on October 31, 1916,

there were two changes to Tower 83's entry along with some new information. The

commissioning date changed to July 14, 1910, about four months later than the

date originally listed, and the function count increased from 20 to 29. This

was also the first such table in which RCT designated the railroad responsible for

operating the interlocker; this new information specified that the KCM&O held

this responsibility. Tower 83's entry remained static in RCT's annual lists

until the table published December 31, 1926 showed the function count as 13, a

drop of more than half. The cause and effect of

this change has not been determined. The list published two years

later reverted to the original count of 20 functions, and the listing remained

unchanged through the end of 1930, after which RCT stopped publishing an annual

list.

Tower 83 was converted to an automatic plant on March 9, 1933

according to records in the RCT interlocker archives maintained at DeGolyer

Library, Southern Methodist University. Santa Fe designed and installed the new

interlocker, and its complexity was discussed in great

detail in the December, 1934 issue of

Railway Signaling. Notwithstanding the

article's headline description of Chillicothe being located "in the Texas

Panhandle", and accepting the premise that "ramifications" equates to "advanced features"

when the author describes the new system as "...an

automatic layout that embraces most of the ramifications yet attempted",

and ignoring the potential conflict in the article's statement that "Several years ago, an obsolete mechanical

plant was removed from service at this point, for the reason that the expense

incurred in its operation and rehabilitation was not warranted by the amount of

traffic handled." (since ... if "several" is more than "two", this

assertion becomes difficult to reconcile with RCT's

table of interlockers dated December 31, 1930 showing Tower 83 active), hence, despite all of these concerns and regardless of

whatever old equipment may have actually been in place at the time, the article

does an admirable job of explaining the new system which was apparently quite

sophisticated.

RCT had approved the first

two automated interlockers in Texas in 1930, and the Chillicothe crossing fit

the profile of a limited traffic location that would be a candidate for an

automatic system to avoid the expense of staffing a manned tower. The

interlocker couldn't be eliminated because the railroads felt "...signal

protection and a means of reducing train delays at the crossing were highly

desirable in view of the numerous switching movements made in the vicinity of

the crossing." The article discusses the need to ensure

that

trains stopped at nearby passenger depots did not tie up the signals governing

the crossing, and it highlights that "...16

main-line switches included between the four approach signals of the plant

conspire to make the application of automatic interlocking difficult." It

certainly sounds impressive, and you can read all about it!

In contrast to the KCM&O route, which became at best a break-even

proposition while Santa Fe kept it alive for additional decades, the FW&D

through Chillicothe experienced no such issues. Its long term success was mostly

attributable to its named endpoints, Fort Worth and Denver, which supplied the traffic critical to making the line viable. This was

particularly true in the early days c.1890. Amarillo is now a major city and

rail junction, but it came into existence only because enterprising

settlers found a good spot for a town as the FW&D built through that area. The

FW&D was ultimately merged into the Burlington system, so the tracks through

Chillicothe now belong to Burlington's successor, Burlington Northern Santa Fe

(BNSF).

Above: Facing northwest at the site of Tower 83, the

KCM&O / FW&D diamond was somewhere along this track segment. Presumably the

tower would have been visible in the early days. Note the north-facing signal;

the adjacent signal would soon be removed and the new one rotated to face west

along the tracks. (Google Street View 2013) Below:

This Google Earth image from August, 2019 shows two locomotives parked on a

remnant of the KCM&O main track a short distance north of the Tower 83 crossing.

They are presumably associated with the Louis Dreyfus Commodities grain elevator

located just off the map farther north, where a large balloon track has been in

place since approximately 2008. US Highway 287 is a short distance off the

bottom of the image.

Above: This view looks north toward the

grain elevator operation from the Ave. F grade crossing. Note the cars parked on the balloon track in the

distance. (Google Street View 2013)

Below

Left: Mike Newton took this photo of the Santa Fe depot in May,

1995. Below Right: The Santa

Fe depot is barely visible trackside in the distance in this photo also taken by

Mike in May, 1995. The Tower 83 crossing diamond sat nearby, discarded in the

weeds behind the camera. The camera faces south, and the home signal to the left

of the track was visible from US 287

and remained illuminated red for a period of time after the diamond was removed.

![]()

Last Revised: 1/9/2024 JGK - Contact the Texas

Interlocking Towers Page.