Texas Railroad History - Tower 128, Ballinger and Tower

129, Tuscola

Two Crossings of the Abilene and

Southern Railway and the Santa Fe Railway South of Abilene

|

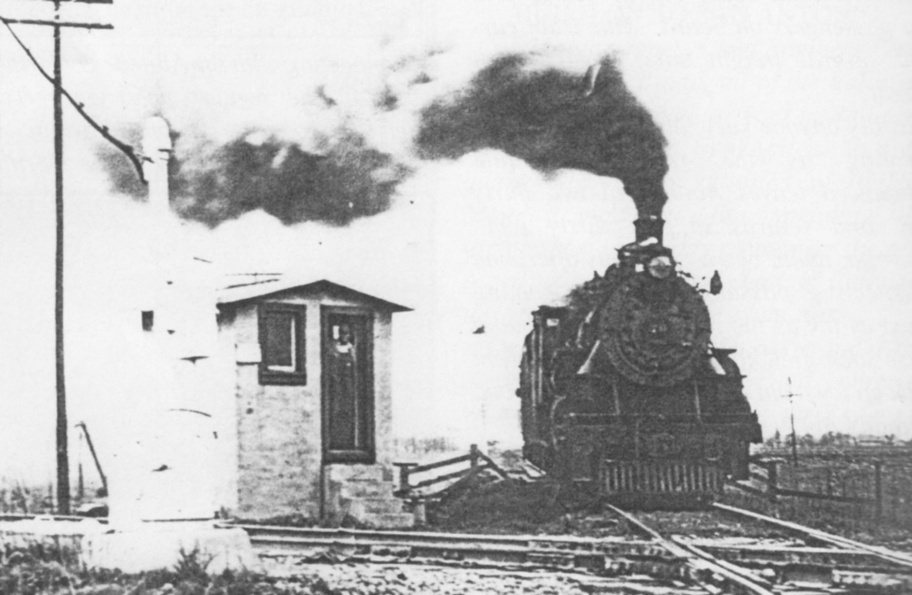

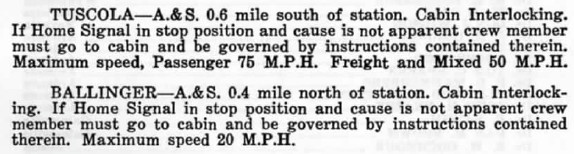

Left: In this undated

photo from the A. C. Greene collection (Journal of Texas Shortline

Railroads, Vol. 2, No. 1, 1997), an Abilene & Southern (A&S) locomotive

is passing the Tower 129 cabin interlocker at Tuscola. Prior to crossing

the Santa Fe tracks in the foreground, A&S trains would stop so that a

crewmember (presumably the man in the doorway) could enter the cabin to

set the interlocker controls to display STOP on Santa Fe's home and

distant signals, and activate its derails. The interlocker would delay

effecting the changes for a suitable period should a Santa Fe train

already be near the crossing. After the A&S home signal changed to PROCEED

and the derails were cleared, the train could proceed over the diamond. The

controls

would then be reset to the standard position, reversing the signals and

derails on both tracks to grant unrestricted movements for

Santa Fe trains. The A&S had no distant signals at Tower 129.

Instead, fixed signs reminded approaching trains they were nearing the Santa Fe crossing and

that a stop at the cabin was

required.

The

semaphore-style home signal is barely visible trackside to the left

behind the locomotive (a better picture from the opposite direction is

below.) The most likely scenario is that the

locomotive had stopped short of the home signal (failing to do so

would derail the locomotive.) The crewmember disembarked to enter the

cabin and change the

controls. The PROCEED signal was granted and the

derails were cleared, hence the locomotive moved forward and is about to cross the

diamond. The crewmember will set the controls back to the normal

position and reboard his train heading northeast to Abilene. |

Right:

This undated photo is from the collection of Joe Dale Morris (Journal of Texas Shortline

Railroads, Vol. 2, No. 1, 1997.) The view is northeast along the A&S

toward Abilene. The horizontal home semaphore indicates STOP, and what

may be a derail mechanism on the left rail (just beyond the signal pole)

appears to be engaged (i.e. over the rail.)

The Tower 129 cabin and

interlocking plant were installed by Santa Fe which also took

responsibility for maintenance. As the second railroad at the crossing,

Santa Fe funded the capital expense, but the recurring expenses for

utilities and maintenance were shared by both railroads. After a final

inspection by the Railroad Commission of Texas (RCT), the plant was

placed in service on

March 15, 1927. RCT records show the Tower 129 interlocking plant having

six functions, but their allocation among combinations of signals,

switches and derails is undetermined. At least by 1937 and perhaps from

the outset, there were switches at both ends of a connecting track in

the east quadrant that may have been controlled from the cabin.

Tower 129 was the last of three consecutive cabin

interlocker projects that RCT authorized for Santa Fe, probably

in the summer of 1926. The others were Tower 127 at Tenaha and Tower 128

at Ballinger. The tower numbers reflect

the order in which projects were initiated, but they do not indicate the

order of installation. Every project was different; some took longer to

complete than others. Though it was the last to be started, Tower 129

was the first to commence operations. Six weeks later, Tower 128 began

operation on April 27, 1927. It very likely had the same design, but no photographs have been found.

About a year later, Santa Fe installed Tower

127, an almost identical cabin. A

year after that, another virtually identical Santa Fe cabin,

Tower 152 at Wharton, was commissioned. |

|

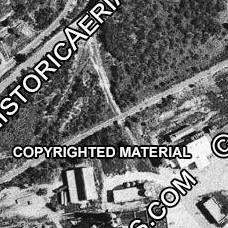

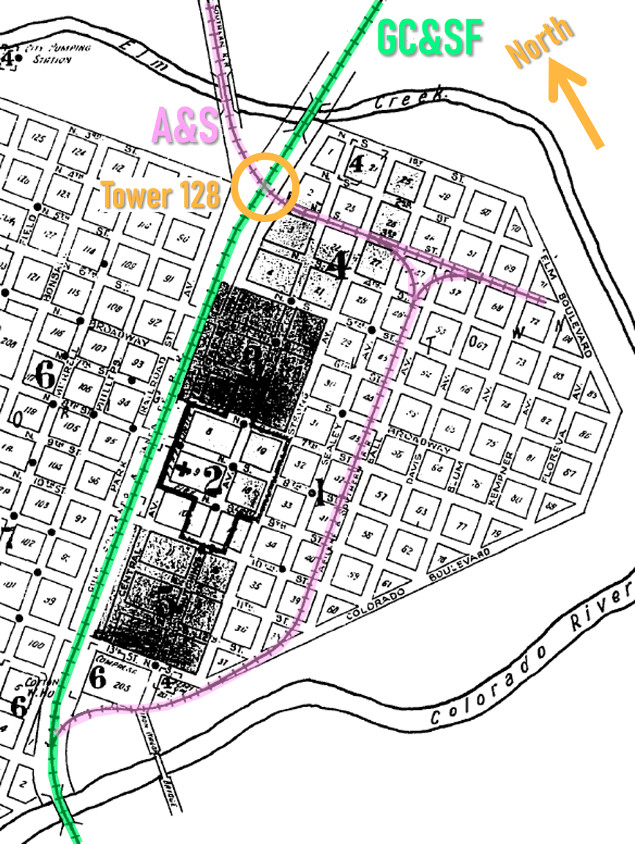

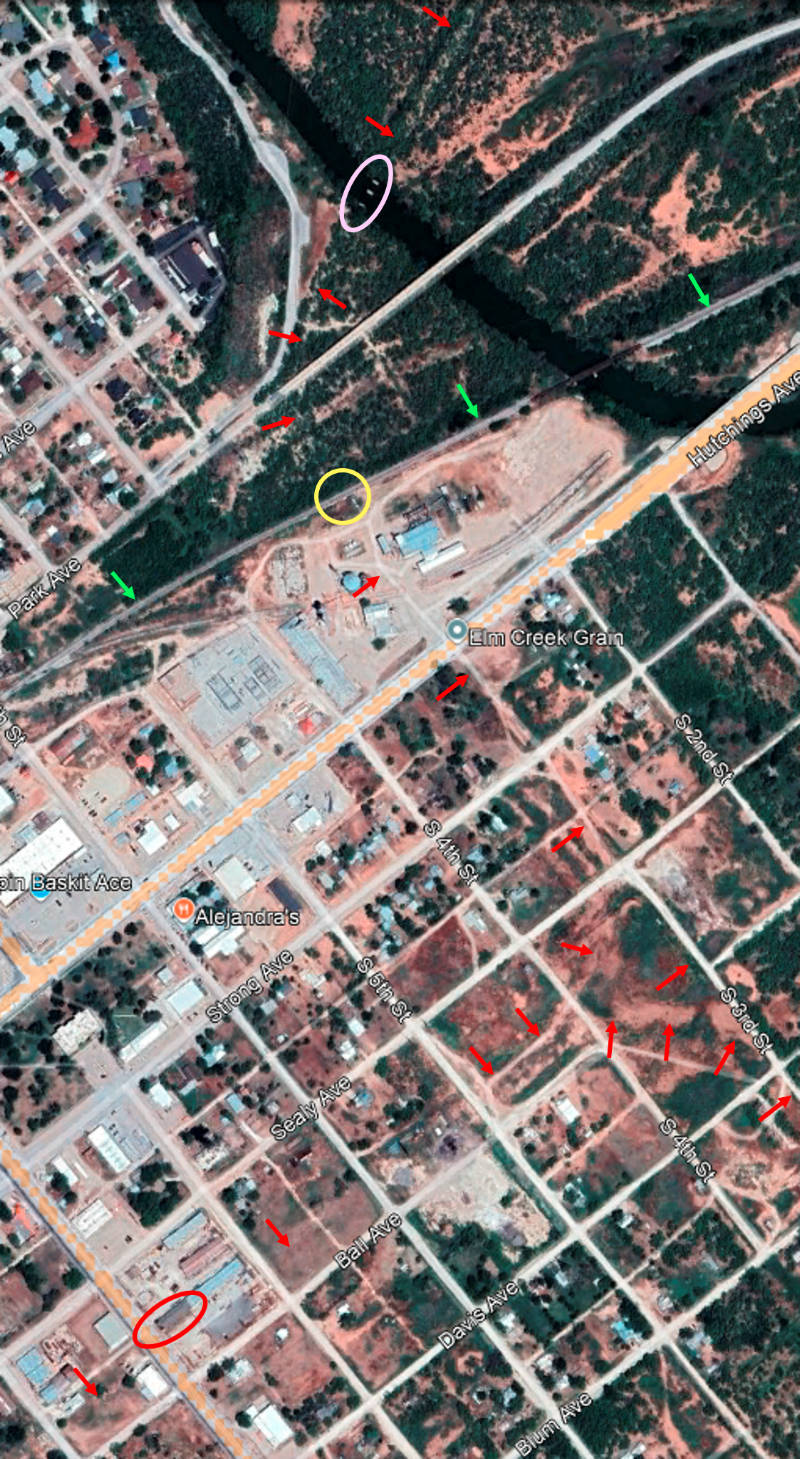

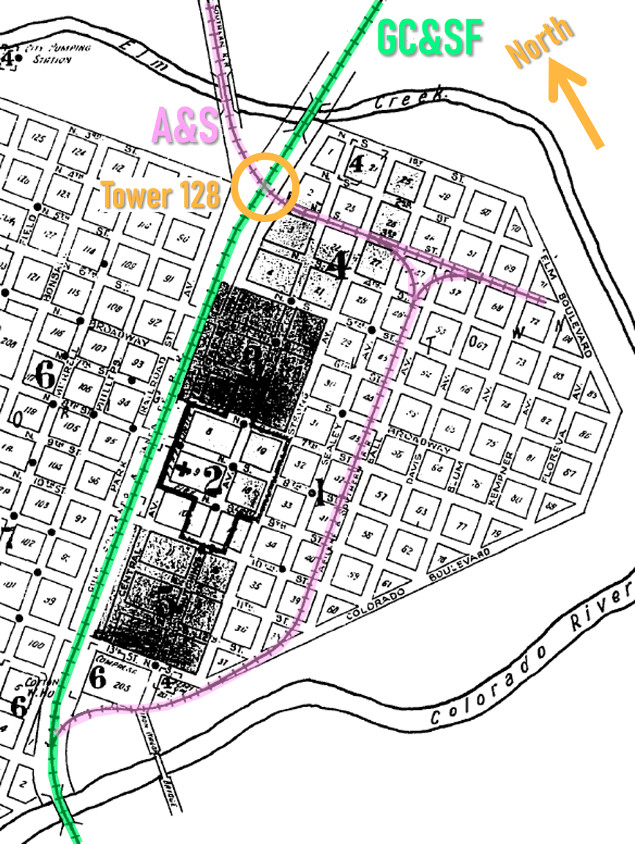

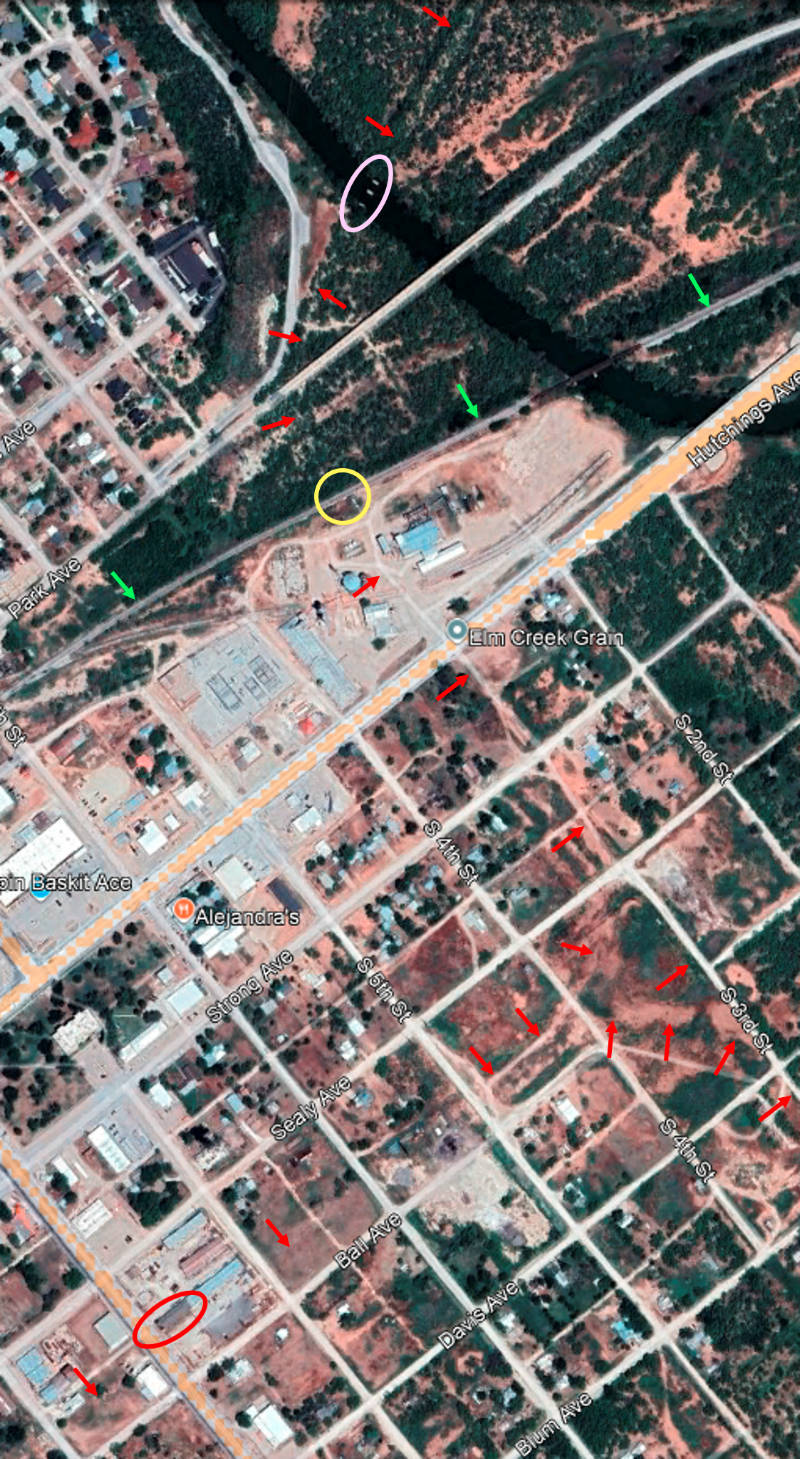

Right: This aerial image from 1937 ((c)

historicaerials.com) shows the A&S (pink arrows) and the Gulf, Colorado

& Santa Fe (GC&SF) Railway (green arrows) at Ballinger. The tracks

formed an 'X' pattern (yellow circle) in which the Tower 128 cabin is visible as a white dot in the

south quadrant. It was probably identical to the Tower

129 cabin. The image shows a connecting track (blue arrow) between the two

railroads in the west quadrant. North of the crossing, Park Avenue

passed over the A&S on a bridge (red oval.) All three of the Elm Creek

bridges -- Park Avenue, the A&S, and the GC&SF --

are visible in the image.

Above: Twenty years

later, the Tower 128 cabin casts a prominent shadow to the north in this

image from 1957 (left.)

Though another two decades elapsed, it was still standing to cast a

shadow to the west in this 1976 image (right)

some four years after the A&S line was abandoned at Ballinger. The cabin was removed at least by 1983 per

historic aerial imagery. (both images (c) historicaerials.com) |

|

Above: This August, 2023

Google Street View facing east from a parking area in the Ballinger City Park

shows an A&S bridge abutment (red oval) at the south bank of Elm Creek. The A&S

tracks continued south in the foreground semi-parallel to the Park Avenue bridge and then curved

east to pass beneath the roadway, heading for Tower 128.

In 1881, the Texas & Pacific (T&P) Railway worked with

ranchers and other landowners in Taylor County to found the town of Abilene as

it built west toward El

Paso. With substantial

population growth, Abilene incorporated in 1883, becoming the county seat. Soon

thereafter, as the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe (GC&SF) Railway began building a

northwest extension out of Temple heading for New

Mexico, Abilene's newspaper became convinced that Santa Fe's crossing of the

T&P would be at Abilene. Santa Fe tracks reached Brownwood in December, 1885,

and in early 1886, construction resumed westward heading for the town of

Coleman, a cattle shipping point about fifty miles southeast of Abilene. It was

during this timeframe that Santa Fe decided to build a branch line to San Angelo to capture

potential livestock shipping business.

The junction for the branch was chosen to be five miles

shy of Coleman, just beyond the new town of Santa Anna where a town lot sale was

held on May 4, 1886. Ever optimistic, the Abilene Reporter

was certain that the building of a branch line to San Angelo "...almost insures Abilene

the main line which will be extended on here from Coleman. ... Abilene is to be

congratulated on San Angelo's success." (January 25, 1886, as quoted by the

Galveston Daily News.) Tracks reached Coleman

in March, 1886 but went no further as the construction crews were redeployed to

the San Angelo branch. It was completed in 1888 and began carrying the bulk of the traffic.

To the disappointment of many, Coleman

remained the terminus of a 5-mile stub track for twenty-five years.

The San Angelo branch

was effectively the main line, hence the

branch point became known as Coleman Junction (...and decades later,

San Angelo Junction, after the northwest extension resumed out of

Coleman and eventually began

to carry a majority of the traffic.)

|

Left Top:

The GC&SF began surveying its route west from

Coleman Junction to San Angelo in the fall of 1885. The right-of-way

(ROW) through Runnels County

did not pass through the county seat, Runnels City. Its 250

residents objected by sending a delegation to Galveston to

appeal directly to the management of the GC&SF. (Austin

Weekly Statesman, January 21, 1886.)

Left, Bottom: Having

completed construction into Coleman, work started on the line west

from Coleman Junction soon thereafter. (The

Taylor County News, March 5, 1886)

Right: (Galveston Daily News,

June 4, 1886) The Runnels

City delegation was unsuccessful. The GC&SF preferred to pass five miles

to the south where they founded the new town of Ballinger, named for William

Ballinger, a prominent

Galveston attorney and GC&SF stockholder. The townsite was on the Colorado River

providing a superior water supply

compared to Runnels City. The railroad offered free lots to anyone

relocating from Runnels City. Apparently everyone did because Runnels

City soon drifted into ghost town status. A town lot sale was

held at Ballinger on June 29, 1886. By 1888, Ballinger had become the

county seat and was a wild west boomtown. |

|

As spring became summer in 1886, the GC&SF's construction focus turned elsewhere;

Ballinger would be the end of the line, at least for a couple of years. A few

months earlier,

negotiations led by GC&SF President George Sealy

had

resulted in an agreement under which the much larger Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe

(AT&SF) Railway would acquire the GC&SF on favorable terms if the GC&SF

quickly completed three

construction projects in north Texas and Oklahoma. The GC&SF proceeded to lay three hundred

miles of track in one year to finish the projects required by the agreement. The acquisition proceeded as planned in 1887

and the GC&SF began

operating as a wholly-owned subsidiary of the AT&SF.

In late May,

1888, the GC&SF resumed building west from Ballinger toward San Angelo, 36 miles

away. The first task was to bridge the Colorado River at the south edge of

Ballinger. A story in the Austin Weekly Statesman

of May 31, 1888 noted that

San Angelo's railroad committee was "...having some annoyance in

securing right-of-way and depot grounds..." which had been promised to the

GC&SF. The situation was no better at Ballinger. Across the

Colorado River, "...right-of-way has been purchased at the rate of $150 per

acre...about two miles from town, which could not have been sold for more than

$5 or $10 per acre." The planned route of the railroad beyond Ballinger was

well known by land speculators, hence prices had

skyrocketed during the two year delay. With no other viable option, Santa Fe

paid the price and the first construction train was reported arriving into San Angelo on August

6th. Santa Fe officially accepted the branch to San Angelo from the contractor in early

September.

The railroad topology of the Abilene / San Angelo area

remained generally static until construction of the Kansas City, Mexico & Orient

(KCM&O) Railway commenced at Sweetwater in 1904. This was to become part of a

lengthy main line between San Angelo and Wichita, Kansas. It was a bitter pilll

for Abilene to swallow. With only one-fifth the population of Abilene,

Sweetwater had won the race for the next railroad in the area, and it was a

major line extending through Oklahoma into Kansas. Abilene finally gained

its second

railroad in 1907 when the Abilene & Northern (A&N) began operating

north to Stamford. The Wichita Valley Railway (WVRy) owned a line between

Stamford and Wichita Falls, thus the A&N facilitated a route

between Abilene and Wichita Falls through a section of northwest

Texas noted for its large ranches. One of the founders of the WVRy was

Morgan Jones who became its first president. Jones was a Welsh immigrant

with a successful and well-known body of work building Texas railroads.

Selling his stake in the WVRy, Jones turned his attention to Abilene and the

long held belief that there should be an Abilene - San Angelo railroad to

connect two towns of similar size eighty miles apart.

Jones and other investors chartered the Abilene & Southern (A&S) Railway

to build south from Abilene to San Angelo, continuing to Sonora, another

major livestock center. Jones' survey of the area led him to decide that a direct route

south-southwest out of Abilene toward San Angelo was feasible for about

forty miles to the community of Winters, but from there, it was best to

turn due south for sixteen miles into Ballinger. From Ballinger, Jones

planned to continue the main line southwest to Sonora while also building a

branch to San Angelo that would parallel the existing GC&SF tracks.

|

Above Left: Under a large

headline "A Most Auspicious Day For Abilene" and a subhead "First Rail

Laid Today on Morgan Jones' Road", the

Abilene Daily Reporter of January 6, 1909

chronicled the start of construction for the A&S rail

line to Ballinger. Above Right:

Nine months later, the Aspermont Star

of September 16, 1909 reported that rail service between Abilene and

Ballinger had been inaugurated. Despite Jones' plans,

Ballinger would be the south endpoint of the line; the A&S never built to

Sonora or San Angelo.

Left:

This notional map shows Abilene - San Angelo area railroads c.1911.

Santa Fe's Pecos & Northern Texas (P&NT) subsidiary extended the

dormant northwest main line from Coleman to Lubbock

in 1909-11. The P&NT's junction with the T&P near Sweetwater

became known as Tecific and included exchange tracks, but the actual

crossing was grade separated. At Sweetwater, the T&P also had a grade-separated

crossing of the KCM&O main line. On the north

side of Sweetwater, the P&NT / KCM&O crossing was interlocked

(as Tower 88.) |

A&S construction began in January, 1909, and the line

between Abilene and Ballinger went into operation in September. The A&S

right-of-way was near the community of Tuscola, named for a settler's hometown

in Illinois, where a post office

had been granted in

1899. The railroad was a powerful magnet for many residents, and in an

oft-repeated tradition, the community relocated to be along the A&S tracks. As

the relocation began taking place in the spring of 1909, the

Coleman Voice published stories about the

rumored plans of surveyors hired by Santa Fe to map the northwest extension to

be built by its P&NT subsidiary. "They go from here to Post City, a

town on the proposed route from Coleman to Texico..." (April 2, 1909.) The

idea that Santa Fe was actually going to resume construction of the

long-awaited northwest extension was big news in Abilene (and a bigger

disappointment when Santa Fe bypassed Abilene for Buffalo Gap.) Santa Fe's route

was particularly big news for Tuscola's relocating residents when they

discovered the railroad intended to cross the

A&S at a new town to be founded in their vicinity. With relocations already

underway, Santa Fe's new town morphed into the new Tuscola, but Santa Fe owned much of

the land and was able to profit from its route choice.

Right: Galveston

Tribune, September 22, 1909

Santa Fe's plans "... leaked out today

that the road is in negotiation for [a] tract of land ... where their road

will cross the Abilene & Southern ... one mile northeast of Tuscola."

(Abilene Daily Reporter, June 18, 1909)

Left and Below: Abilene

Daily Reporter, March 25, 1909

|

|

Santa Fe had

become large and powerful, and many Abilene leaders saw it as a bully.

"...the road is going to endeavor to build some towns of its own, and has no

tears of sympathy for any place that it may destroy or injure..." (Abilene

Daily Reporter, June 18, 1909.) A lengthy letter from Texas Governor Thomas M.

Campbell to Santa Fe President E. P. Ripley dated June 4, 1909 expressed alarm

with the planned route of Santa Fe's northwest extension, asserting that "...your

line as proposed is close enough to established towns to injure them, but ... it

systematically avoids all or many of them." Campbell, a former General

Manager of the International and Great Northern Railroad, made it clear that he

was prepared to assert the power of the State to rectify the situation. But the

chosen route was not entirely Santa Fe's fault. The major towns, Abilene and

Sweetwater, had grown considerably since the 1880s, with their downtown land

profitably utilized. Finding a right-of-way into town (or worse, condemning one)

would have been difficult, expensive and time-consuming. Santa Fe elected to

serve Sweetwater with a 3-mile spur, but its closest approach to Abilene

remained at Buffalo Gap, a dozen miles away. In the end, nothing came of Gov.

Campbell's letter. Santa Fe launched service to Buffalo Gap and Sweetwater in

1910, and the Snyder Signal of Friday, May 19,

1911 reported that "the first through train on the Santa Fe between

Sweetwater and Lubbock passed through Snyder Sunday."

|

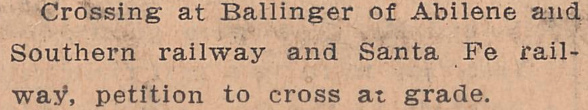

Above:

The

Galveston

Tribune of August 7, 1909 listed items to be discussed at

RCT's meeting later that day. The docket included the petition for a

grade crossing at the planned A&S junction with the GC&SF at Ballinger. The two railroads had been notified a month earlier

(below,

Denton Record & Chronicle,

June 30, 1909) that a hearing on this topic would be held. The article

asserts that the application requested an "interlocker and other

safety crossing devices."

The petition was granted, but RCT did not order

installation of an

interlocking plant. Nearly eighteen years later on April 27, 1927, RCT

commissioned Tower 128 at Ballinger, an unmanned

cabin with a 4-function mechanical interlocking plant. Six weeks earlier

on March 15, 1927, the

Tuscola crossing had been interlocked as Tower 129. Like the Tuscola

cabin, the Ballinger cabin meant that A&S trains

always stopped to have a crewmember enter and set the controls to permit

his train to cross. This would also signal approaching Santa Fe trains that the

diamond was occupied. After

his train had passed, the crewmember would reset the

controls to the normal position so that the signals permitted unrestricted movements by Santa

Fe trains.

Left: This 1915

Sanborn Fire Insurance index map of Ballinger has been highlighted

to show the two railroads. Both crossed Elm Creek on the

north side of town and quickly converged to the authorized grade

crossing (which would be interlocked twelve years after this map was

drawn.) The A&S had tracks through town that reconnected to the GC&SF

near its bridge over the Colorado River. The A&S tail

track and wye on 3rd Street facilitated turning

its trains around to go north. |

In 1926, the A&S became owned by the T&P, which had

been enlarging its territory by acquiring various short lines with which it

intersected. In 1929, the T&P applied to the Interstate Commerce Commission

(ICC) for permission to extend the A&S from Ballinger to San Angelo, a reprise

of Morgan Jones' original plan. San Angelo's residents were clamoring for a

second railroad because the KCM&O was no longer a viable independent railroad.

It had been in and out of bankruptcy, and finally had been acquired by Santa Fe. Regardless of

the clamor, the ICC refused to approve T&P's plan.

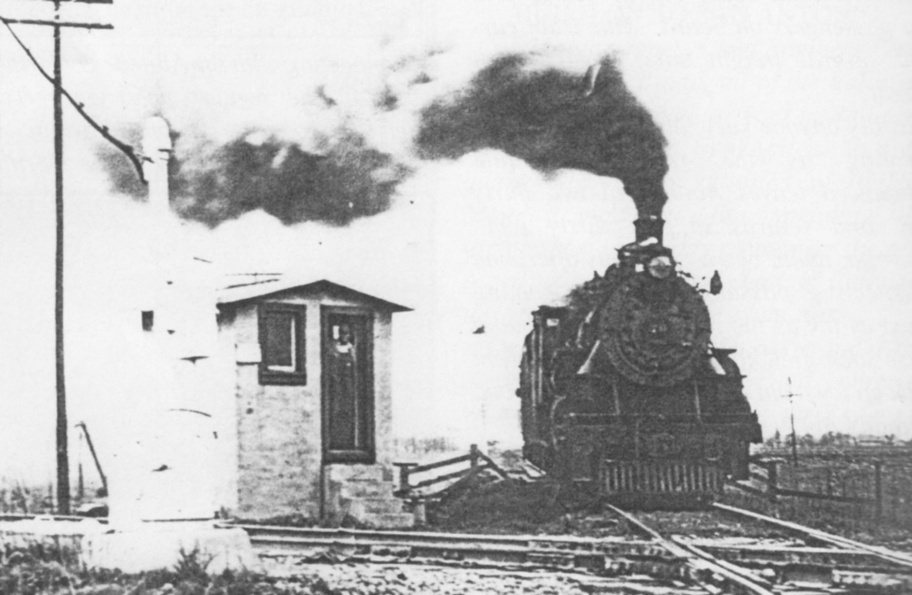

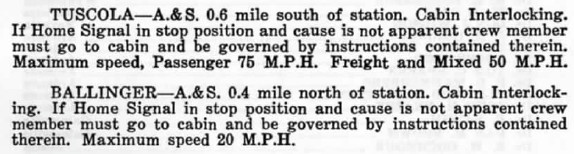

| Right:

A Santa Fe Employee Timetable from April, 1964 contained this note about

the cabin interlockers at Tuscola and Ballinger. Later timetables show no indication

that either crossing was ever converted to an automatic interlocker. There was no

incentive for the A&S to seek to automate either interlocker because it

had relatively infrequent traffic over the line and its trains were

operating slowly near the crossings anyway due to the proximity of its depots and yards. The delay to stop

at the cabin did not substantially affect A&S operations. Santa Fe had

no incentive to automate either plant because its trains never

stopped unless the crossing was occupied, a situation that would be no

different with an automatic interlocker, a much more expensive plant to

maintain. |

|

|

Left:

This 2024 Google Maps image has been annotated to show the path (red

arrows) of the A&S at Ballinger. It entered from the north on its

bridge (pink oval) over Elm Creek (below,

Jim King photo 2009 with the Park Avenue bridge in the background.)

The A&S then curved east to cross (yellow circle) the Santa Fe tracks (green

arrows) and continued down what is now S. 3rd Street (below),

which remains ill-defined as viewed southeast from Hutchings Ave. (Google

Street View, August 2023.)

The tracks continued along S. 3rd St., forming a wye where the track

curved to the southwest to parallel Ball Ave. This was the depot lead to

reach the A&S depot (red oval) which still stands.

This Google Street View image (below) looks north from S. 7th St. showing the long

(east) wall of the depot which faced the tracks.

Ballinger is

rare in that it had two stone depots that are both still standing. The Santa

Fe depot (below) sits

on the southeast side of the tracks at N. 7th St., off the left edge of

the image. (Jim King photo, 2009)

|

In 1972, the sixteen miles of A&S track from

Ballinger to Winters was abandoned; the remaining 31 miles through Tuscola into Abilene survived until

1988. Though the train frequency is low, the GC&SF tracks through Ballinger are

still in operation, now owned by Texas Pacifico Transportation. To the west, the

line extends to San Angelo (GC&SF origin), and continues to the international

bridge at Presidio (KCM&O origin.) To the east, it goes to San Angelo

Junction (originally Coleman Junction) where it connects with

Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF), the corporate successor resulting from Santa Fe's

merger with Burlington Northern in 1995. BNSF operates the former GC&SF / P&NT

Santa Fe main line.

|

Left:

William Thompson provides this photo from the late 1980s showing him and his

fellow crewmembers about to cross the Santa Fe line at Tower 129 toward Abilene.

Since it was owned by the T&P, the A&S was absorbed into Missouri

Pacific (MP) when MP merged the T&P in 1976. MP had owned a controlling

interest in T&P stock since the 1930s, and the railroads had

collaborated closely for decades. In 1982, Union Pacific (UP) acquired MP

as a wholly-owned subsidiary which continued to operate under its own

name until the late 1990s. On the day pictured, MP had assigned UP

locomotive #2124 to work the A&S route.

Above: This 1937

aerial image ((c)historicaerials.com) shows Tower 129 in the south

quadrant of the crossing casting a shadow to the north. A connecting

track is visible east of the diamond and it remains intact through 1966

imagery, and possibly as late as 1983. It would have supported movements

between Abilene and Brownwood, but its actual use is undetermined. |

The function of the connecting track at Tuscola is

undetermined, but it is interesting to speculate that it could have been used as

an alternate route to Fort Worth for the T&P if a major accident or bridge

outage curtailed use of the main line east of Abilene. Eastbound T&P traffic

toward Fort Worth could take the A&S at Abilene to Tuscola and use the connector

to switch to Santa Fe's tracks to Brownwood. From there, a direct line to Fort

Worth existed, owned by Santa Fe post-1937 (and by the Fort Worth & Rio Grande

before then.) The connector also could have served Santa Fe as a means of

exchanging northbound cars from Temple into Abilene, or moving southbound traffic out of Abilene to Temple and beyond. Santa Fe had

an exchange with the T&P at Tecific, but for Abilene traffic, it was only useful

for movements in the opposite direction, i.e. eastbound on the T&P into

Abilene, and westbound on the T&P out of Abilene.

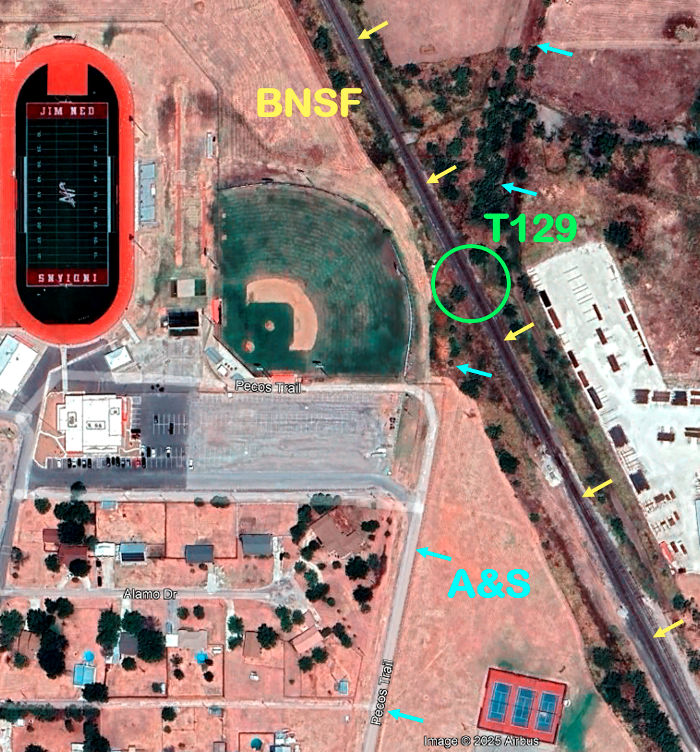

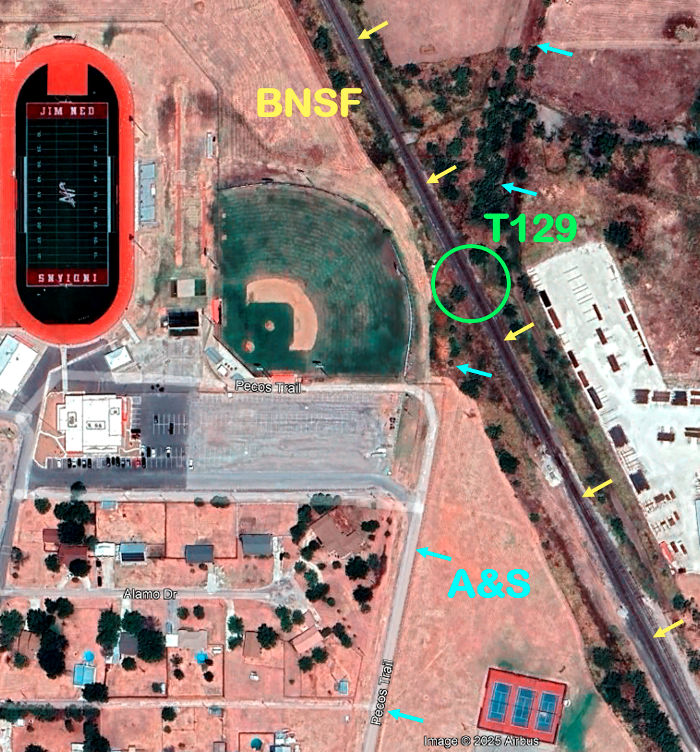

Right:

This recent Google Maps image of the Tuscola crossing shows its proximity to

the baseball stadium of nearby Jim Ned High School. The tracks are 450

ft. from home plate; a homerun could hit a passing train, but it would

take a major league slug! The A&S tracks would have been closer down the

right field line, but the stadium appears to have been built after the

A&S was

abandoned in 1988. The A&S ROW south of the crossing was paved to

become Pecos Trail, a road used for access to the parking lot for the

football stadium and baseball field.

Above: At the north

end of the A&S ROW on Pecos Trail, the BNSF tracks are visible at right,

angling toward the Tower 129 crossing directly ahead.

Below: At the south

end of Pecos Trail, the roadway ends at 8th St. but the ROW continues

straight. This straight section of A&S track was 3.7 miles

long (both images, Google Street View.)

|

|

Above: This Google Street View

from August, 2023 looks southeast from BNSF's Brown Ave. grade crossing at

Tuscola. The track at left is part of a siding approximately 5,700 ft. in

length. Historic aerial imagery shows that the switch in the foreground was

actually Santa Fe's depot lead. The station was trackside a thousand feet from

this switch, sitting between the main line and the depot lead which passed on

the "street side" of the station. The depot lead continued farther south and

reconnected to the main line about 1,800 feet from this switch, as it does so

today. The Santa Fe depot is visible in 1958 aerial imagery, but is no longer

present in 1966 imagery.