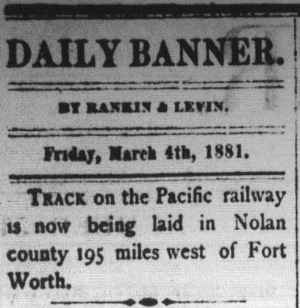

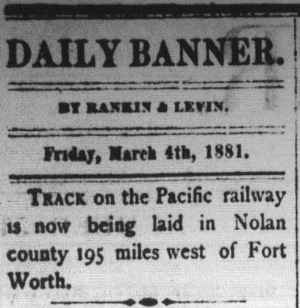

Above: Tracks entering Nolan County was front page news in the Brenham Daily Banner of March 4, 1881.

A Crossing of the Pecos & Northern Texas Railway and the Kansas City, Mexico & Orient Railway

|

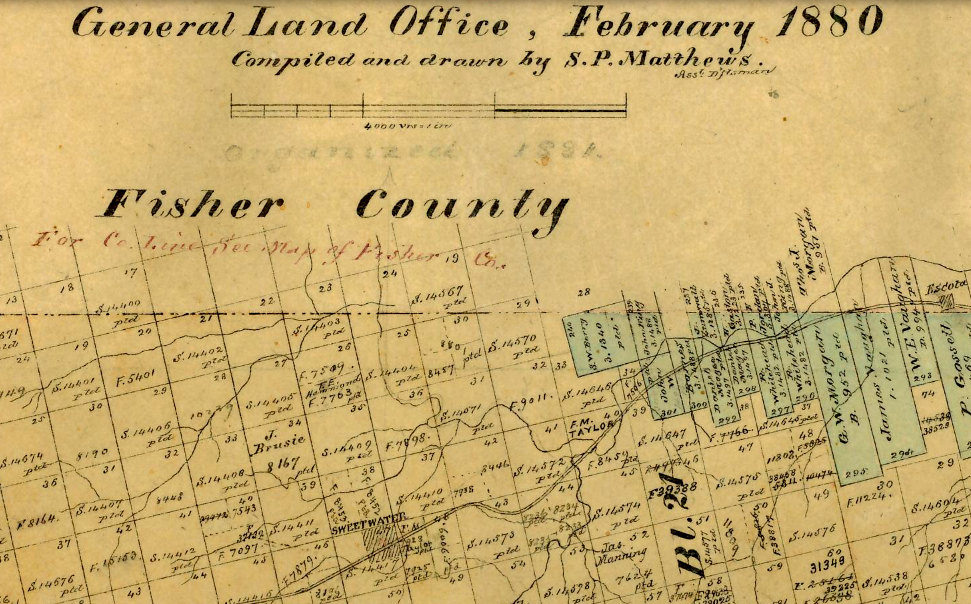

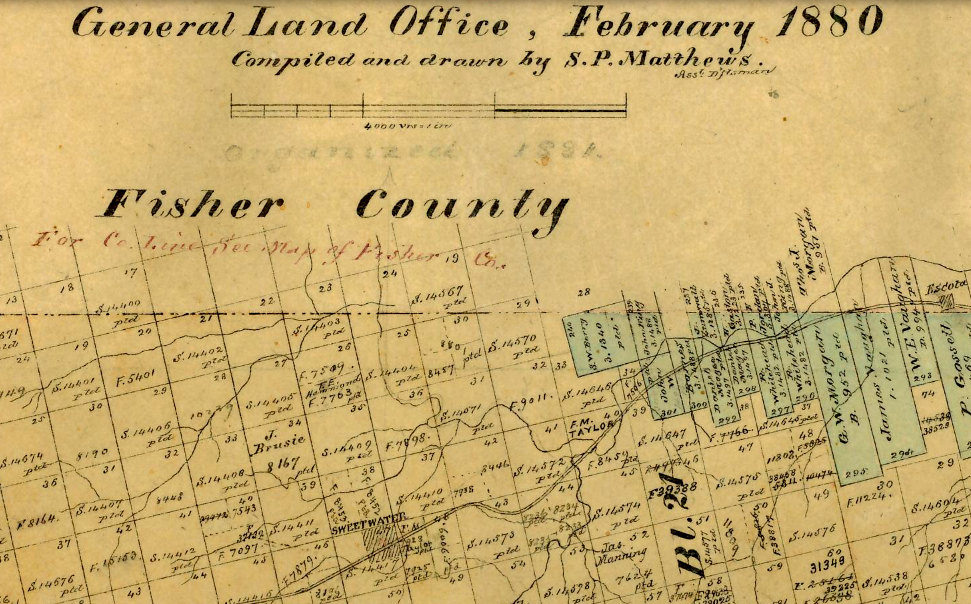

Left:

This map of Nolan County from early 1880 depicts Sweetwater as a small

settlement on the future path of the Texas & Pacific (T&P) Railway. The

T&P line had been surveyed through Sweetwater, but the tracks didn't arrive

until March, 1881. A Post Office had been granted in 1879 under the name "Sweet

Water" but newspapers and just about everyone else used the single-word

spelling. (Texas General Land Office) Above: Tracks entering Nolan County was front page news in the Brenham Daily Banner of March 4, 1881. |

Shortly after Nolan County was organized in 1881,

Sweetwater was selected to be the county seat, its name stemming from the quality of water in

a nearby creek. At the time, Sweetwater was a tiny tent settlement that had

been around for only a few years; the Galveston Daily News

has references to it dating only to 1877. It was a good option for

the county seat because it was on the surveyed

right-of-way of the Texas & Pacific (T&P) Railway, the only community of any size

on the T&P in Nolan County (but since the county only had 640 total residents in

1880, size must be viewed in context.) The T&P tracks from Ft. Worth arrived in

March, 1881, and the Brenham Weekly Banner of

March 17, 1881 reported that "...through mail and express trains now run to

Sweetwater..."

The T&P was headed for

El Paso; its Federal charter had established a target destination of San

Diego, but due to financing delays, building to southern California was no

longer feasible. Southern Pacific (SP) had already occupied most of the T&P's

surveyed route across Arizona and New Mexico, and would soon reach El Paso, so a

T&P/SP compromise was reached. For towns like Sweetwater, the end result was the

same; the T&P became a direct route to California, albeit by interchange with SP

at El Paso. From the east, the T&P had come through

Dallas and Fort Worth after starting in

Texarkana, where there were connections to the

Midwest and beyond. Sweetwater's population grew

steadily and it did not take long

for a rivalry to develop with its predecessor stop on the T&P, Abilene, forty miles east.

Both towns sought to lure the next railroad in the region, and it was widely

accepted that a southeast-to-northwest railroad would sooner or later cross

somewhere in the vicinity of the two towns.

The inevitable "next

railroad" near Abilene and Sweetwater was assumed to be the Gulf,

Colorado & Santa Fe (GC&SF) Railway. By December, 1885, GC&SF tracks from

Temple had reached Brownwood, and the grade had

been extended to Coleman. Branch line construction to San Angelo began in 1886

five miles south of Coleman. Ever optimistic, the

Abilene Reporter was certain that the branch line "...almost insures

Abilene the main line which will be extended on here from Coleman. ... Abilene

is to be congratulated on San Angelo's success." (January 25, 1886, as

quoted by the Galveston Daily News) Tracks were

laid into Coleman in March, 1886, but the grade went no further. The San Angelo

branch was completed in August, 1888 by which time the GC&SF had been acquired by the much

larger Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway. No one knew it at the time, but

neither San Angelo nor Coleman would see a resumption of Santa Fe construction

for twenty years.

Above: The CVRy contract with Sweetwater required its general offices and other major facilities to be located there. (Wills Point Chronicle, August 18, 1897) |

While Abilene waited on Santa

Fe to restart construction at Coleman, Sweetwater aggressively pursued a

new railroad, the Colorado Valley

Railway (CVRy). The CVRy had been chartered in April, 1897 by citizens of

Robert Lee, the county seat of Coke County forty miles due south of

Sweetwater. The original plan

was to run from the T&P at Colorado City through Robert Lee to San Angelo,

more or less a straight line route, but Sweetwater really wanted

this railroad. Sweetwater was the same distance from

Robert Lee as Colorado City and was likewise on the T&P. Sweetwater was smaller

in population, but it made a better offer, $80,000 in direct financial

aid with an agreement that the CVRy would locate its headquarters and

shops in Sweetwater, a provision that would be tested in court a decade

later. To aid the CVRy and to

attract more railroads, Sweetwater built a town lake in 1898 suitable for watering steam locomotives. Right: The Abilene Reporter of October 1, 1897 reported on the commencement of CVRy track-laying south toward Robert Lee and San Angelo, reminding those in Abilene who had predicted no rails would ever be laid by the CVRy that they should not be so quick to declare that "no trains will ever be run over it." A frequent gripe in Abilene newspaper editorials was that local leaders were much too passive, waiting for railroads to show up instead of going after them. |

|

Perhaps to the chagrin of Abilene readers, an anonymous

citizen ("Old Texan") wrote a letter to the Editor of the Abilene Reporter

(December 10, 1897) to describe

being on the first CVRy

excursion train out of Sweetwater, five miles south. The evidence

as to whether additional CVRy tracks

were ever laid beyond five miles is mixed, but by mid summer, the CVRy had run out of

cash. The

El Paso Daily

Herald of August 9, 1898 (quoting the

Pecos Valley Clippings) reported that the contractors working on the CVRy

had been unable to pay their employees, apparently because they had not been

paid by the CVRy for work performed. A few weeks later, the

Taylor County News of October 14,

1898 (quoting the Sweetwater Reporter)

announced that the CVRy had sought bankruptcy protection.

The demise of the CVRy was

due simply to being undercapitalized, a common flaw for railroads started by

small town investors. In bankruptcy, CVRy

management recognized the need to reduce the overall cost of the enterprise and

reorient the business toward its most effective route. Although interests in

Robert Lee had chartered the CVRy, the local topography suggested that bypassing

it ten miles to the east would substantially reduce the overall construction

expense between Sweetwater and San Angelo, the towns that had the commercial

potential to make the line a success. A ten mile branch to Robert Lee

would then become feasible. There was still no

direct connection between the T&P and the

ranching counties west of Brownwood. Such a connection would provide competition

to Santa Fe for livestock shipments from San Angelo to Fort Worth, an important

processing and meatpacking center. If the CVRy could get its finances repaired, a Sweetwater -

San Angelo railroad remained an attractive proposition.

By early 1899, the CVRy was

ready to emerge from bankruptcy. The El Paso International Daily Times

of May 12, 1899 reported that an alternate route surveyed from Sweetwater to San

Angelo that would bypass Robert Lee was expected to reduce construction costs by

$180,000. On July 28, 1899, the

El Paso Daily Herald reported that the CVRy

charter had been revised to change its name to the Panhandle & Gulf (P&G)

Railway. This revision officially removed Colorado City from the charter and specified the railroad's endpoints as

San Angelo and Sweetwater, where the general offices would be located. The new name,

however, pointed toward a more ambitious plan involving a much greater distance,

but the charter revision did not elaborate.

|

Left: The Abilene

Reporter of December 15, 1899 reprinted a

Sweetwater Reporter editorial that

hinted at

exciting railroad news coming to Sweetwater. In particular, the "north"

reference conveyed insider knowledge. Right: The El Paso International Daily Times of March 27, 1900 revealed that the P&G was part of a "gigantic enterprise" that was being launched by Arthur Stilwell. How long this affiliation had been in place is not reported, but it did note that the P&G charter had been filed with the Texas Secretary of State recently, presumably an update to the CVRy charter revision that had occurred in the summer of 1899 when the P&G name was first established. According to the article, the P&G would run from "the northern boundary of Texas south through Sweetwater, San Angelo, Spofford Junction and to Laredo." Spofford Junction was the location on the Southern Pacific (SP) Sunset Route between Uvalde and Del Rio where SP's branch to Eagle Pass departed the main line. Stilwell's new railroad was the Kansas City, Mexico & Orient (KCM&O) Railway, intended as a short route to the Pacific port of Topolobampo, Mexico, and ostensibly 400 rail miles closer to Kansas City than California ports. In January, only two months prior to this news item, Stilwell had publicly revealed his plan for the KCM&O at a dinner held in his honor in Kansas City. That same January, he had resigned as President of the Missouri, Kansas & Texas Trust Co., and only a few months earlier, he had lost control of the railroad he had founded, the Kansas City, Pittsburg & Gulf (KCP&G, today's Kansas City Southern Railway.) Unhappy about losing his railroad, but always pressing forward, Stilwell was wasting no time getting started on his next railroad project. |

|

In railroad circles, the prevailing wisdom was that

capitalizing on Sweetwater's east / west T&P connection would require a north /

south railroad with a significant population center at the other end. Without it,

local commerce would be insufficient to support the line. Hence, San Angelo was

the sole focus; there was virtually no population north of Sweetwater. Its residents

truly would be astonished at the idea of building to some point

north, yet building north was what Stilwell needed. To

comply with state law, he had been looking for a Texas corporation with a

state railroad charter authorizing construction in west Texas. The P&G fit

his plans perfectly, so he negotiated to have it become part of his route to

Mexico. The newspaper's hint of northward construction suggests

that Stilwell had already been in contact with the P&G in the fall of 1899,

perhaps only weeks after he had been removed from the KCP&G's management.

A charter amendment filed by the P&G explained that it was becoming part of

Stilwell's enterprise, and it specified that P&G rails would meet KCM&O tracks

at the Red River in Hardeman County. It also implied that after Sweetwater and

San Angelo, Sonora would be its next major town to the south. Despite the report

in the El Paso International Daily Times, the

filed amendment did not actually name Spofford Junction as a crossing point (but

did cite its county, Kinney County.) The terminus at Laredo also wasn't named;

it was inferred because Webb County was

the last one listed. The counties south of San Angelo had

most likely been included in the charter revision as a means of establishing

territorial intent and perhaps as a bit of deception. South through Sonora was not the short route to

Topolobampo; Stilwell had already decided to cross into Mexico at Presidio, Texas,

southwest of San Angelo. In January, 1903, a P&G stockholders meeting was held

in Sweetwater to elect Stilwell and other KCM&O executives formally as officers and

directors of the P&G.

Despite the excitement

engendered by the P&G's incorporation into Stilwell's grand plan,

construction forces did not descend upon Sweetwater. A route between

the Red River and Sweetwater had not been surveyed, nor had Stilwell approved the

new route to San Angelo surveyed by the P&G in early 1899. Grading work north of

Sweetwater appears to have commenced in the spring or summer of 1902, at least

two years after the P&G had become part of the KCM&O enterprise. The San

Angelo Press of July 30, 1902 reported that grading "150 miles from

Sweetwater to the Red River will have been completed" by November 1. That

matches later newspaper reports of grade work between Sweetwater and San Angelo

commencing early November, 1902, perhaps by construction teams no longer needed

north of Sweetwater.

Col. T. Yates Walsh was the KCM&O's construction

superintendent, and he relocated to San Angelo in the fall of 1902 to supervise

the work on the southern end of the route. The completion of grading between San

Angelo and Sweetwater may be inferred from the news of Col. Yates (and his wife

Emilie) returning to their home in Baltimore about a year later, as reported by the

San Angelo Press of September 2, 1903. "Col.

and Miss Walsh have been in San Angelo for several months and have come to be

regarded as one of us. We dislike to see them go but they may return someday and

when they do they may rest assured of a hearty welcome." Despite a home in

Baltimore, Yates remained employed by Stilwell and he returned frequently to

Sweetwater and San Angelo as the next phases of construction got underway.

|

Shortly

after Yates moved to San Angelo, P&G's attorney, Judge H. C. Hord of Sweetwater, filed maps with the Railroad Commission of Texas (RCT) for

a route between

Sweetwater and San Angelo. The Alpine Avalanche

(February 13, 1903) reported details of Hord's submission, including that

the new route was "...a distance of seventy-six miles. About one third of

this mileage has been graded." Also, the P&G had "...abandoned

the old grade of the Colorado Valley road, which runs south from Sweetwater for

a distance of twenty-five miles, including ten miles of track which has been

taken up." Perhaps the right-of-way was

retained from Sweetwater to the tiny community of Maryneal, aligned perfectly

with Robert Lee, and the "abandoned...old grade" was

south of there. From Sweetwater, the KCM&O did build south to Maryneal but veered sharply away from Robert Lee southeast to

Blackwell before turning south again, bypassing rough terrain

toward Robert Lee by locating the tracks farther east. Left: The Bonham News of July 26, 1907 carried this announcement of a sale of town lots at Maryneal. The "Orient" reference tends to imply tracks to Maryneal being operational, but doesn't actually say so. There's no mention of excursion trains for buyers, nor is the full name of the railroad ever cited. Objectively, this looks more like a real estate promoter's attempt to capitalize on future tracks to Maryneal. Pre-1910, no record of tracks to (or through) Maryneal, nor anything vaguely similar, appears in RCT construction records as compiled in Texas Railroads: A Record of Construction and Abandonment (Charles Zlatkovich, University of Texas, 1981.) The only possible exception is CVRy construction from Sweetwater to "Milepost 7.25" in 1899. If this is the trackage over which CVRy ran their 1897 excursion south from Sweetwater, why is it listed as 1899? Did RCT require the P&G to "back-report" CVRy's existing tracks as part of its charter revision? More confusing, Zlatkovich lists the 1905 construction to Sylvester (22 miles north of Sweetwater) as starting at "Milepost 7.25" for 14.89 miles. Is this the same Milepost 7.25? A summary of 1903 construction published by the Houston Post (December 26, 1903) lists 1.9 miles of P&G track "north" from Sweetwater. Neither this nor six miles built northward by the P&G in 1904 (as reported by newspapers) are listed by Zlatkovich. These omissions could easily account for a north starting point of "Milepost 7.25", if that term was actually part of the original construction record, and not merely an assumption made by Zlatkovich. If the reported construction to Sylvester in 1905 was less than the 22 miles from Sweetwater (because it started where the unreported 1904 construction ended), might Zlatkovich have assumed an extension of existing tracks? If so, the construction to Milepost 7.25 in 1899 was the only option; it is RCT's only other CVRy or P&G construction record. The Sweetwater Reporter editorial quoted in December, 1899 casts doubt on the idea that the CVRy "Milepost 7.25" construction went north. "Don't be astonished should the road be in course of construction to some point north within twelve months..." If such northward construction had already occurred for 7.25 miles in their own back yard earlier that same year, why would anyone be astonished if it were to resume? The potential astonishment pertained to the idea of building north from Sweetwater to begin with, something no one was considering in 1899. |

|

Left: The San

Angelo Press of October 13, 1904, quoting the

Abilene News, reported that

track-laying had stopped six miles north of Sweetwater, supposedly due

to cash flow issues. It also carried the rumor that the Chicago, Rock

Island & Pacific Railway, a major railroad in the Plains and Midwest,

was attempting to buy the Orient. Right: The San Angelo Press of February 9, 1905 carried a story about letters being written to the Texas Legislature (which controlled railroad charters) questioning the Orient's claim that they would soon resume work north from Sweetwater. Note that the P&G name was still in use as the Orient's Texas subsidiary. Changing the name to align with the parent company was initiated at a P&G stockholders meeting in July, 1905 and it officially became the "Kansas City, Mexico & Orient Railway of Texas" (but everyone just called it "the Orient".) Work was returning to Sweetwater. The Baylor County Banner of January 27, 1905 was able to print a personal letter that a Seymour resident had received from a correspondent in Sweetwater that read "Fifteen cars of steel arrived here yesterday, and the construction train for the Orient arrived this morning." |

|

Despite the imminent restart of construction north from Sweetwater in early 1905, the KCM&O's good faith was being challenged from all sides. Much of it came from San Angelo, which was not happy to see construction heading north from Sweetwater, clearly contrary to the impression conveyed by Col. Yates less than a year earlier. Rumors began to swell that the reason the KCM&O was not building to San Angelo was simply that they had decided to abandon the grade they'd already built in favor of a trackage rights agreement with the T&P between Sweetwater and Pecos. "The distance from Sweetwater to Pecos City is about 240 miles. From the latter point it is understood that the Orient will build via Fort Stockton into the Republic, the preliminary survey between Pecos City and Stockton having already been made." (Dallas Southern Mercury, February 2, 1905, using "Republic" as shorthand for Republic of Mexico.) Whether such an arrangement was considered is undetermined, and it did make sense at some level. But the reason for building north from Sweetwater was simple: the entire line south of Wichita, Kansas and across Oklahoma was nearing completion, but served very little purpose through sparsely populated country. Crossing the Red River and proceeding into Sweetwater provided a meaningful endpoint since a connection could be made to the T&P, which provided west coast access through its SP interchange at El Paso. At least this would provide the potential for west coast traffic to and from Wichita.

|

Left and Right: In late June, 1905, construction

reached the new town of Sylvester, on the Clear Fork of the Brazos

River, 22 miles northeast of Sweetwater. A Fourth of July gathering was

planned, including two days of free excursions

out of Sweetwater, as reported by the

Fort Worth Record & Register on

June 27, 1905. Beyond Sylvester, construction continued with rails reaching Knox City in 1906 and Benjamin in 1907. Work resumed north from Benjamin in May, 1908 and reached Crowell in late August. Beyond Crowell, the building of the Pease River bridge began in the summer of 1908. In September, track construction coming south from Oklahoma crossed the new Red River bridge, passed through Chillicothe and continued south. The north and south track crews joined the final rails at the Pease River bridge in January, 1909. Trains between Wichita, Kansas and Sweetwater began operating on January 31, 1909. |

|

|

|

Left:

The bonus and right-of-way agreement that Stilwell had reached with the leaders

of San Angelo and Tom Green County had long expired, as had a renegotiated

agreement. Stilwell was ready to try again, but he had to do so in person, so he

traveled in his private car, passing through Ballinger on the Santa Fe branch to

San Angelo. (Ballinger

Banner-Leader, January 12, 1907) Stilwell made San Angelo an offer they could not refuse: he would forgo the $50,000 bonus in the original deal if San Angelo citizens would subscribe to $200,000 in second mortgage bonds. The KCM&O would also make San Angelo the headquarters of its Texas operations including general offices, machine shops, etc., and it would be the junction point for "the Del Rio and Fort Stockton lines." Within a few months, Orient contractors began grading the first mile of track in San Angelo south of the North Concho River, the endpoint being about where the main KCM&O complex and passenger depot would be built. This put San Angelo citizens at ease, but Sweetwater cried foul. It claimed the original CVRy contract guaranteed Sweetwater to be the Texas headquarters for the Orient. When the KCM&O denied the obligation, Sweetwater filed in district court for an injunction to prohibit moving the Orient's base to San Angelo. |

The KCM&O appears to have maintained a presence in San Angelo in 1907 and 1908 while the lawsuit worked its way through the courts. Work was done within the city and initial track-laying to the north got underway, but rather slowly. Nearly two years after Stilwell's visit to San Angelo, the Coleman Voice reported in its November 6, 1908 edition that "...the road is graded from Sweetwater to San Angelo, seventy-eight miles, and twelve of it has been laid with steel, north of San Angelo, and is in operation." But the grading had been completed in 1903, so, other than minor grade repairs (from sitting dormant for four years), the work in 1907 and 1908 consisted of laying twelve miles of track. The tracks "in operation" were probably carrying work trains and nothing else. Serious track-laying did not get underway until the spring of 1909, and work progressed from both ends. An Alpine Avalanche story on August 26, 1909 stated "...fifty-one miles has been built, twenty-two miles south from Sweetwater and twenty-nine miles north from San Angelo." The story also noted that the northward construction was halted at the Colorado River where a 1,876-ft. steel bridge was about 25% complete. Finally, a headline in the Alpine Avalanche of September 23, 1909 declared "Orient Reaches San Angelo".

|

Sweetwater won at the district

court (left,

Abilene Reporter, September 27,

1909) and an injunction was issued prohibiting the Orient from

relocating its shops and offices to San Angelo. The case was appealed to

the Second Court of Civil Appeals which upheld the district court's

injunction (below,

Knox City News, July 8, 1910).

A final appeal to the Texas Supreme Court followed, and Sweetwater lost. (right, Snyder Daily

Signal, May 31, 1911)

|

|

About the time Stilwell reentered the Texas rail scene

with the P&G in 1900, Santa Fe was beginning to expand its operations

in the Texas Panhandle. Santa Fe's Texas subsidiary for Panhandle railroads, the

Southern Kansas Railway, had established its general offices in

Amarillo in 1900 (the Southern Kansas name would be

changed to Panhandle & Santa Fe, "P&SF", in 1914.) In 1901, Santa Fe acquired the

Pecos and Northern Texas (P&NT) Railway and various affiliated lines in eastern

New Mexico, all controlled by railroad investor James J. Hagerman. In

1899, the P&NT had built a line from

Amarillo southwest via Canyon to the state line (at

the future site of Farwell)

across from Texico, New Mexico. From Texico, Hagerman's line continued southwest

to Portales and beyond.

The Belen

Cutoff was opened by Santa Fe in 1908 across eastern New Mexico, providing

a lower grade route for Los Angeles - Kansas City traffic via Clovis, New Mexico

and Amarillo compared to the mountainous route via Raton Pass on the Colorado -

New Mexico border. The Belen

Cutoff also created the opportunity for a direct Santa Fe route between Houston and

southern California if the tracks at Coleman could be extended northwest toward

Clovis. By the summer of 1910, Santa Fe had built south from Canyon through

Plainview to Lubbock, and from

Lubbock south to Lamesa. The Lamesa line passed through the new town of Slaton,

fifteen miles southeast of Lubbock where Santa Fe had acquired a large tract of

land with the intention of building a division headquarters. Slaton would become the target connecting point

for the northwest extension from Coleman, but to reach the Belen Cutoff, trains

at Slaton would have to proceed north through Lubbock and Plainview to reach the

Amarillo - Clovis line at

Canyon. From there, Clovis was 85 miles west. In 1914, Santa Fe opened

a much shorter direct line between Lubbock and Farwell, eliminating the routing through Plainview and Canyon.

To build the Coleman Cutoff, the northwest extension from Coleman to Slaton,

Santa Fe assigned its construction to the P&NT.

In April, 1909, the

Coleman Voice began to

carry stories of Santa Fe surveyors passing through town. "They go from here

to Post City, a town on the proposed route from Coleman to Texico..."

(April 2, 1909) The precise route north of Coleman was a focus of Abilene interests,

and they were most unhappy to learn that Santa Fe was bypassing their town, going

instead through Buffalo Gap, eleven miles southwest of downtown Abilene. Santa

Fe also bypassed Sweetwater, but not as far; the tracks passed about three miles

northeast of downtown. A lengthy letter

from Texas Gov. Thomas M. Campbell to Santa Fe President E. P. Ripley dated June

4, 1909 expressed alarm with the planned route of the Coleman Cutoff, asserting

that "...your line as proposed is close enough to established towns to

injure them, but ... it systematically avoids all or many of them."

Campbell, a former General Manager of the International and Great Northern

Railroad, made it clear that he was prepared to assert the power of the state to

rectify the situation. But the chosen route was not entirely Santa Fe's fault.

The major towns, Abilene and Sweetwater, had grown considerably since the 1880s,

with their downtown land profitably utilized. Finding a right-of-way into town

(or worse, condemning one) was very difficult; the disruption to residents and

businesses would have been considerable (and thus, expensive and

time-consuming.) Regardless of Gov. Campbell's letter, Buffalo Gap remained the

only depot in the Abilene area, and serving Sweetwater was likely in Santa Fe's plans from the outset.

A 3-mile spur from the main line was built so that the Sweetwater passenger

depot would be close to downtown, near the

Orient depot.

In April, 1909, the

Coleman Voice began to

carry stories of Santa Fe surveyors passing through town. "They go from here

to Post City, a town on the proposed route from Coleman to Texico..."

(April 2, 1909) The precise route north of Coleman was a focus of Abilene interests,

and they were most unhappy to learn that Santa Fe was bypassing their town, going

instead through Buffalo Gap, eleven miles southwest of downtown Abilene. Santa

Fe also bypassed Sweetwater, but not as far; the tracks passed about three miles

northeast of downtown. A lengthy letter

from Texas Gov. Thomas M. Campbell to Santa Fe President E. P. Ripley dated June

4, 1909 expressed alarm with the planned route of the Coleman Cutoff, asserting

that "...your line as proposed is close enough to established towns to

injure them, but ... it systematically avoids all or many of them."

Campbell, a former General Manager of the International and Great Northern

Railroad, made it clear that he was prepared to assert the power of the state to

rectify the situation. But the chosen route was not entirely Santa Fe's fault.

The major towns, Abilene and Sweetwater, had grown considerably since the 1880s,

with their downtown land profitably utilized. Finding a right-of-way into town

(or worse, condemning one) was very difficult; the disruption to residents and

businesses would have been considerable (and thus, expensive and

time-consuming.) Regardless of Gov. Campbell's letter, Buffalo Gap remained the

only depot in the Abilene area, and serving Sweetwater was likely in Santa Fe's plans from the outset.

A 3-mile spur from the main line was built so that the Sweetwater passenger

depot would be close to downtown, near the

Orient depot.

Right:

general orientation of the railroads in the vicinity of Sweetwater by the end of

1911.

Santa

Fe was operating regular service past Coleman to Buffalo Gap at least by August

19, 1910 when the Abilene Daily Reporter noted

that the first carload of freight had been received at the

Buffalo Gap depot. On October 20, 1910, the Lampasas

Daily Leader quoted a Brownwood Bulletin

report that Santa Fe scheduled service between Temple and

Sweetwater would begin November 1st. On January 4, 1911, the

El Paso Morning Times explained that the

remaining gap between Slaton and Coleman consisted of 68 graded miles between Post and a point a

dozen miles northwest of Sweetwater. The town of Snyder was in this gap, and the

Snyder Signal of Friday, May 19, 1911 reported

that "the first through train on the Santa Fe between Sweetwater and Lubbock

passed through Snyder Sunday."

Bypassing the main part of

Sweetwater placed Santa Fe's crossings

of the T&P and the KCM&O into rural areas a few miles from town. The

layout of the T&P crossing would be critical because the railroads anticipated

significant interchange traffic through

Sweetwater, yet neither wanted to see delays caused by trains waiting to cross the diamond. The solution was a grade-separated crossing that also had a

lengthy parallel exchange track nearby, a location that Santa Fe called "Tecific".

Unlike Tecific,

Santa Fe's crossing of the KCM&O was a simple diamond interlocked at grade

for which RCT commissioned Tower 88 on October 10, 1912. Tower 88 was initially

listed by RCT as a 15-function electrical interlocker. By all indications, it

was a manned tower. Most towers were two stories, but there was at least one

single-story manned tower (Tower

71) in operation by this time, and photos of the remnants of Tower 88's

foundation and its limited size suggest that it might have been only a single

story. In 1916, RCT published an additional detail

noting that the KCM&O was responsible for interlocker operations. This was

somewhat unusual; for manned towers, the second railroad at the crossing

typically built the tower and took operational responsibility, but the KCM&O

tracks were there first (at least by January, 1909 when service to Wichita

began.) Since this crossing was created after 1901, RCT regulations required the

second railroad, Santa Fe, to fund the capital expense of the interlocker, but

the railroads were required to share the recurring operating and maintenance

(O&M) expenses of the tower.

In a table published December 31, 1926, RCT

completely revised the information for Tower 88. The commissioning date was changed

to July 10, 1911 (a puzzling historical revision that served no relevant

purpose), the function count was reduced to eleven, and the interlocker

operation was reassigned to Santa Fe (listed as the P&SF; all prior reports had

listed the P&NT as the other railroad at Tower 88, but the P&NT existed only on paper

and had long been leased to the P&SF.) This listing remained unchanged through

the final comprehensive table of interlockers published by RCT on December 31,

1930. (Subsequent annual reports issued by RCT would sometimes note new or

changed interlockers, but a comprehensive table was no longer published.)

What changed in 1926? The details are unknown, but it was likely a

restructuring of the interlocker to be less expensive to operate and maintain.

Arguably, it could represent conversion from a manned tower to an unmanned cabin interlocker which would have

eliminated the staffing expense. Train crews on the less busy line (the Orient)

would have operated the controls, stopping each time they needed to cross,

temporarily setting the signals to allow passage and then resetting them after

crossing to allow unrestricted movements on the busier line. The listed interlocker type didn't change, however, that alone is

not conclusive. Of the three known places where manned towers were replaced by

cabin interlockers, RCT changed the listed interlocker type for two of them (Tower

5 and Tower 40) to reflect the cabin style. The

third, Tower 62, remained listed as interlocker

type "Mechanical" in the final table of 1930, even though it had been converted

to a cabin interlocker in 1922 and thus should have been listed as "M.-Cabin".

Also, for cabin interlockers, RCT's designation of the "operating railroad"

appears to have pertained to the railroad responsible for maintaining

the interlocker rather than which train crews were actually operating

it. The signals were always left to allow unrestricted movements on the busier

line. While crews on the busier line rarely needed to operate the interlocker,

it did happen; the interlocker incorporated timeout functions and controls to

allow a crew to override a signal that wouldn't clear properly. The Orient was

in the midst of dire financial and legal issues, so if Tower 88 was

converted to a cabin interlocker in 1926, the P&SF had the strong incentive to

take responsibility for maintaining it since the vast majority of trains passing

over the diamond belonged to them.

The function count of eleven is significant. Given the proximity of Tower 88 to

the north end of Santa Fe's yard and the presence of Sweetwater Junction (the

depot spur) about 3,000 ft. south of Tower 88, northbound Santa Fe trains had no

need for a distant signal, typically placed a few thousand feet from the diamond

to warn approaching trains if they needed to slow in anticipation of stopping at

the diamond. Even if they were on a main track that bypassed the yard,

northbound Santa Fe trains would be operating slowly near the yard and the

junction, hence the distant signal was not needed. The eleven functions most

likely consisted of a home signal and derail in each of the four directions,

plus three distant signals.

In 1928, after financial issues had placed the KCM&O in and out of

bankruptcy (mostly in!) since 1912, Santa Fe bought the KCM&O and integrated it

into the P&SF Slaton Division. The acquisition was approved by the Interstate

Commerce Commission on August 28, 1928. This presented Santa Fe with the option

of retiring the interlockers at Sweetwater and San Angelo, which only involved

Santa Fe and KCM&O tracks. The final RCT interlocker table showed Tower 82 (San

Angelo) retired but Tower 88 remained listed as operational. It was likely

retired soon thereafter, and certainly no later than 1937 when the Tower 88

crossing diamond was reportedly removed.

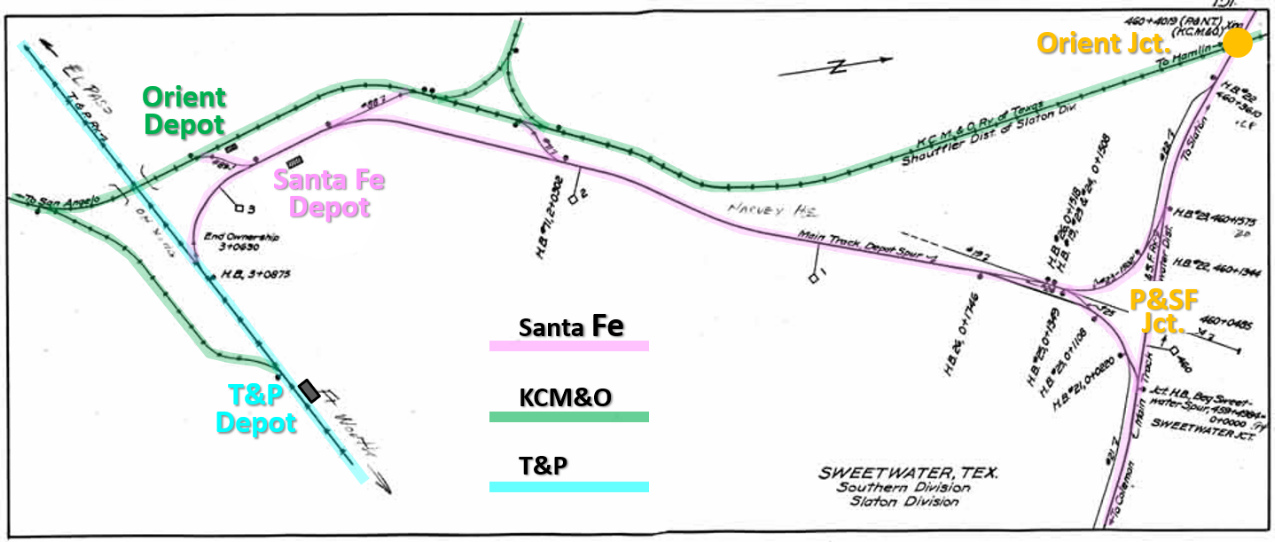

Above: With

north to the right, this annotated Santa Fe junction record (courtesy Santa Fe Railway Historical and Modeling Society) highlights the railroads

and interchange tracks at Sweetwater. It does not, however, show the Tecific interchange

east

of town (off the bottom of the map). The map is from c.1929-30 because the KCM&O

is shown as part of Santa Fe's Slaton Division, and by 1931,

the departure point of Santa Fe's depot spur into town had been renamed P&SF

Jct. (the map shows the original name, Sweetwater Jct.) Santa Fe passenger

trains backed down this spur from the junction to reach the depot. The nearby Orient depot

was closed in 1933 and Orient passenger trains accessed the Santa Fe depot to

and from the south using the crossover adjacent to the depot. Orient trains used

the crossover north of the depot to transition between the spur and the Orient

main to the north. In

1937, the Tower 88 crossing diamond (orange circle) was removed and the location

became known as Orient Jct. A connector on the east side of Orient Jct.

facilitated movements between the Orient main line to the north and the Santa Fe

depot and Orient main line to the south via P&SF Jct. The main Santa Fe yard was

between Orient Jct. and P&SF Jct.

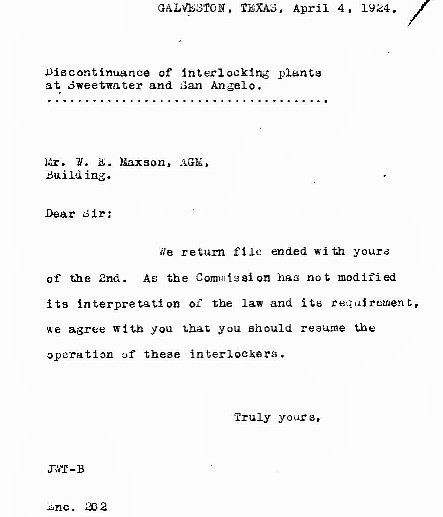

Left:

This letter was sent to W. E. Maxson, Assistant General

Manager of the GC&SF, in 1924. The best guess is that it was written by an attorney

at the GC&SF corporate office ("Galveston"), someone Maxson

recognized simply by their initials, and it was sent to Maxson's office in

the same location (addressed simply as "Building.") It suggests that Maxson had

asked for a legal opinion regarding interlockers at Sweetwater

and San Angelo that Santa Fe had taken out of service. The author agreed with Maxson's

position that Santa Fe should resume operation of both interlockers. The

"interpretation of the law" referenced in the letter relates to legal

issues that had been raised regarding the extent of RCT's authority. For

example, since Texas' interlocker law specifically referred to a

crossing of "another company", could RCT order an interlocker installed

at a junction where all of the tracks belonged to the same company? Under what

circumstances (if any) did a railroad have an inherent right to stop operating

an interlocker (e.g. bankruptcy, merger, temporary or permanent track

abandonment?) Some of these issues had already surfaced with respect to

other interlockers (see

Tower 5, Tower 116 and Tower 121.)

The issue of the scope of RCT's authority would come back to haunt Santa Fe when they voluntarily chose to install an interlocker at Canyon

in 1927. (Santa Fe Legal Archives, Houston Metropolitan Research Center. Thanks to Stephen Hesse

for finding this document.)

This letter is difficult to interpret

within the context of what is known about the interlockers at

San Angelo

and Sweetwater. The KCM&O was involved with both, but unlike San Angelo, Santa Fe was not responsible

for operations at Tower 88, at least not "officially" as of 1924 (RCT

began reporting the P&SF as the operating railroad in the annual report

issued at the end of 1926.) Clearly, sometime prior to April, 1924,

Santa Fe had taken over O&M responsibility for Tower 88 and had decided

to suspend operations, likely due to KCM&O's serious financial issues (it was still

in receivership from 1917.) Did Santa Fe do this on their own, perhaps because KCM&O

had stopped paying their share of O&M expenses? Had KCM&O's train count dropped so low that the expense

of a manned

interlocker could no longer be justified? Assuming the "discontinuance" rendered the crossing

uncontrolled (requiring a full stop by all trains on either track), had Santa

Fe installed a gate normally lined against the KCM&O? What was KCM&O's

preference regarding the

suspended interlockers? Assuming Maxson ordered the interlockers reinstated, did

doing so include notification to RCT that Santa Fe was taking over Tower

88's O&M responsibility (hence the change reported at the end of 1926?) These are questions that require additional research

in Santa Fe's

archives. It is likely that Tower 88 was dismantled in the early 1930s, even if

the diamond survived until 1937.

Bill Stein

supplies these three recent photos of the foundation of Tower 88. Thanks, Bill!

Above Left: The tracks crossed

at approximately a 45 degree angle, with the Orient grade running almost due

north and the Santa Fe tracks going northwest (now BNSF, at far left.) The tower

was east of the diamond, and the Orient grade passed through the tree in the

middle of the image and crossed to the left of the foundation.

Above Right: Looking

southeast, the BNSF main line at right leads into the Sweetwater yard. The connector for the

Orient tracks to the north comes off a switch in the distance and runs along

this side of the visible fence line. The foreground shows some kind of concrete

signal post. The camera is on, or very near, the Orient grade.

Below Left: The Tower 88

interlocking plant was electrical, and there were access panels for the crawl

space beneath the foundation where conduit was routed to carry wiring for power

and control signals. The foundation is small, suggesting that Tower 88 might

have been a single-story building, perhaps similar in style to

Tower 103. Below

Right: This Google Earth image from 2017 shows the Tower 88

foundation beside the BNSF tracks. Due south, the abandoned Orient grade is more

clearly apparent. The connecting track to the right rejoins the original grade

to the north to serve a "lay down yard" for storing blades and other components

of electrical power windmills.

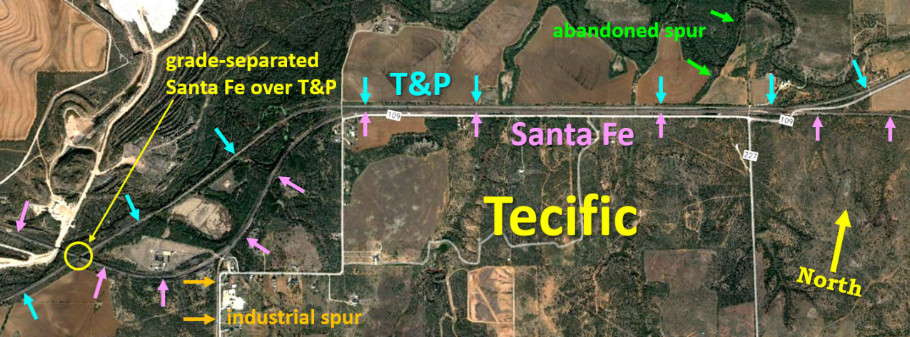

Below: About five miles east of Sweetwater at a junction

known as Tecific, Santa Fe built approximately 1.6

miles of track parallel to and 100 ft. south of the existing T&P tracks.

Historic aerial imagery shows that sidings, crossovers and exchange tracks were

built between them, though most of that trackage is no longer present. There

remains an industrial spur off the former Santa Fe tracks west of Tecific, and

there was also a mining spur going north off the T&P that is now abandoned. West

of Tecific, RCT ordered the Santa Fe to cross over the T&P, as reported by

the Houston Post of January 5, 1910

(below.)

Today, the successor

railroads Union Pacific (UP) and Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) operate the

Tecific tracks (T&P and Santa Fe, respectively), and there is only one siding,

approximately 1.4 miles in length beside the BNSF tracks between the two main

lines. There is one crossover from the siding that facilitates BNSF movements

between Lubbock and UP's tracks to Fort Worth, for which BNSF has trackage

rights.

|

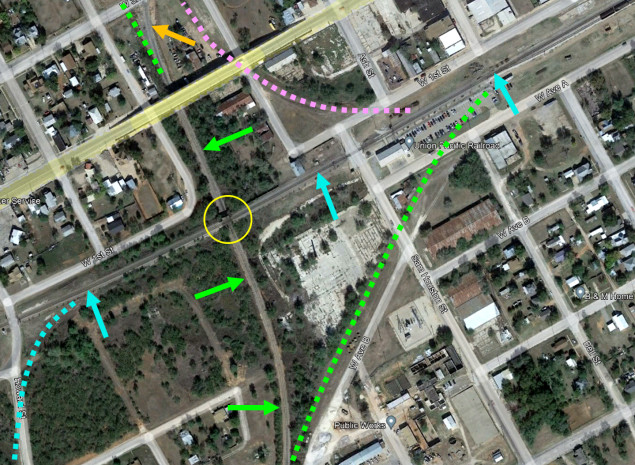

Left:

Orient Jct., the subsequent name for the Tower 88 crossing, is near the center

of this recent Google Earth image. Tracks remain intact in all directions except

south, the KCM&O line into Sweetwater. Although the KCM&O tracks north of

Sweetwater were abandoned in 1995, Santa Fe retained the east side connecting track plus 3,200 ft. of track to the north, up to the grade crossing of Farm Road 108.

In 2009, Wave Wind LLC began building a "lay down yard" along this track for

windmill blades and other components used in wind power production. The south

end of the lay down yard is the white area near the top left corner of the

image. In the lower right corner, the northwest end of Sweetwater Yard is

visible. As discussed above, note the proximity of the yard to Orient Jct. Below: This 2013 Google Street View looking south from the Farm Road 108 grade crossing shows the former Orient tracks intact beside the empty lay down yard. Recent satellite imagery shows considerable activity in the yard.  |

Above Left: Looking south from

the Broadway St. overpass (Google Street View 2021), the former KCM&O tracks

to Maryneal pass beneath UP's ex-T&P tracks near downtown. KCM&O's route through Sweetwater ran north /

south within a wide arroyo west of downtown that narrowed into a ravine to the

south. The elevations of nearby street

intersections show a noticeable dip through the arroyo, suggesting that the T&P

elected to bridge the ravine at the time of their initial track-laying through

Sweetwater. The clearance is not large; the bridge might have been raised during

the KCM&O's construction (a small price to pay to avoid having a crossing at

grade.) The KCM&O simply stayed in the ravine and built

beneath the T&P to connect its new tracks to the north with the original

southward tracks to Maryneal (which remain operational today to serve a cement

plant.)

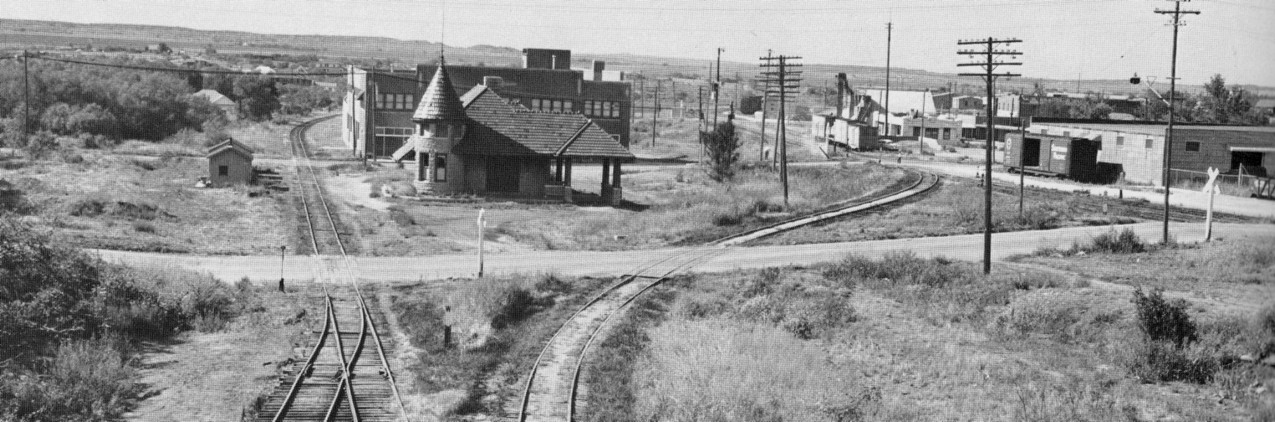

Above Right: The

ornate, stone KCM&O

passenger depot in Sweetwater was abandoned in 1933 but stood for decades

afterward. (Fred Springer photo, May, 1965, Center for

Railroad Photography and Art) Below Left:

In this annotated Google Earth satellite image, Santa Fe's connection to the T&P (pink dashes) remains visible,

though long abandoned. The connecting track

(orange arrow) between the Orient main (green arrows) and Santa Fe's depot spur

has been in place since shortly after Santa Fe acquired the Orient. The original

Orient main north of the depot (green dashes) was retained as an industrial

track at least into the 1960s. South of where the T&P (blue arrows) went over

the Orient (yellow circle), the ROW of the original CVRy track into downtown

(green dashes) remains apparent. This area later held multiple T&P storage

tracks. To the west, the T&P had a wye (the blue dashes mark the eastern lead.)

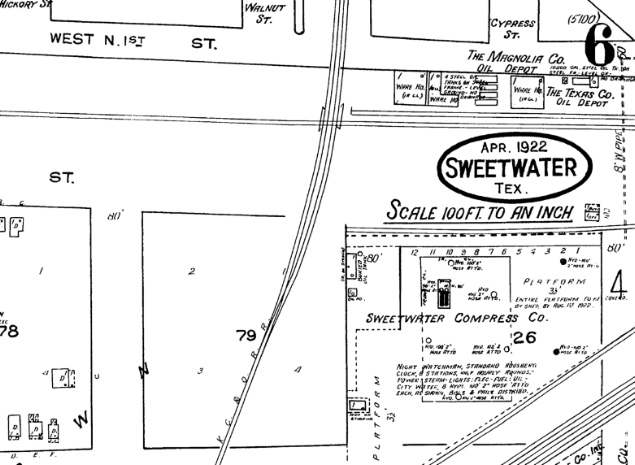

Below Right: This 1922 Sanborn

Fire Insurance map of Sweetwater shows a confusing depiction of the T&P bridge

over two tracks of the KCM&O. If the narrow rectangles beside the KCM&O tracks

are viewed as bridge outlines, then they should be rotated 90 degrees to an east

/ west orientation (see the Santa Fe junction record above.) If they are viewed

as bridge abutments, they are correctly oriented. The crossing does not appear

on any earlier Sanborn map.

Above: Fred Springer took this photo in August, 1958

facing north, probably from the Broadway St. overpass. The Orient depot is

prominent in the foreground, still standing 25 years after it was abandoned. The

former Orient main track to the left of the depot was still in use as an

industry spur. The connecting track in the foreground joined Santa Fe's

depot spur to the Orient main tracks to the south. The Santa Fe depot is the

single-story light-colored building with a large portico visible in the distance

at right. It had been closed since 1953 when a new Santa Fe depot opened along

the main line on the other side of town. (from

Santa Fe Depots, the Western Lines, by Robert E. Pounds, (c) Kachina

Press 1984) Below: Google

Street View in 2019 caught approximately the same view. Both depots are gone,

but the large brown building at 404 W. 4th St. is still standing. The white

house at far left is also partly visible in the 1958 photo.

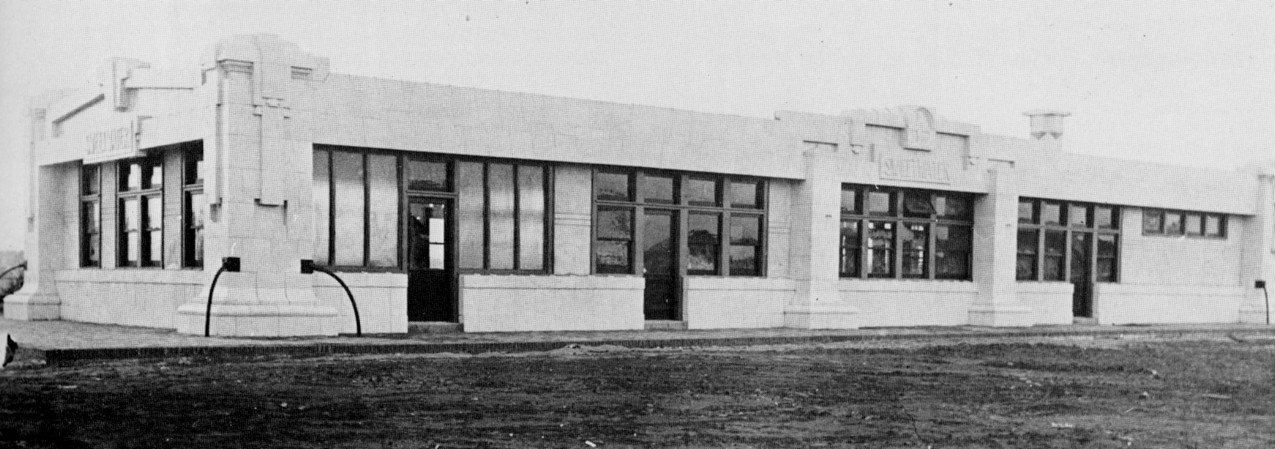

Above:

Opened in 1911, Santa Fe's original

Sweetwater depot was closed in 1953 in favor of a new depot along the main line. (Santa Fe photo, from Santa Fe

Depots, the Western Lines, by Robert E. Pounds, (c) Kachina Press

1984) Below Left: Santa Fe

opened a new passenger depot along the main line east of town in 1953. (Kansas

State Historical Society collection)

Below Right: The 1953 depot building was still standing

when Google Street View imaged the back of it in 2013, apparently in use as a

BNSF Sweetwater yard office (despite the missing 'E'.) The original flat roof

was replaced with a slightly peaked aluminum roof. The building is reached

off Highway 70 by turning onto the appropriately named "Santa Fe Depot Road."

Above:

Opened in 1911, Santa Fe's original

Sweetwater depot was closed in 1953 in favor of a new depot along the main line. (Santa Fe photo, from Santa Fe

Depots, the Western Lines, by Robert E. Pounds, (c) Kachina Press

1984) Below Left: Santa Fe

opened a new passenger depot along the main line east of town in 1953. (Kansas

State Historical Society collection)

Below Right: The 1953 depot building was still standing

when Google Street View imaged the back of it in 2013, apparently in use as a

BNSF Sweetwater yard office (despite the missing 'E'.) The original flat roof

was replaced with a slightly peaked aluminum roof. The building is reached

off Highway 70 by turning onto the appropriately named "Santa Fe Depot Road."

Above Left: T&P depot (H. D.

Connor Collection) Above Right:

By 1930, Missouri Pacific (MP) owned a controlling interest in the T&P, but

did not exercise operational or financial control.

The railroads worked closely for decades and the T&P was officially merged

into MP in

1976. UP acquired MP in 1982. This photo of the MP depot in Sweetwater was taken

July 1, 1983. (Texas Historical Commission photo)