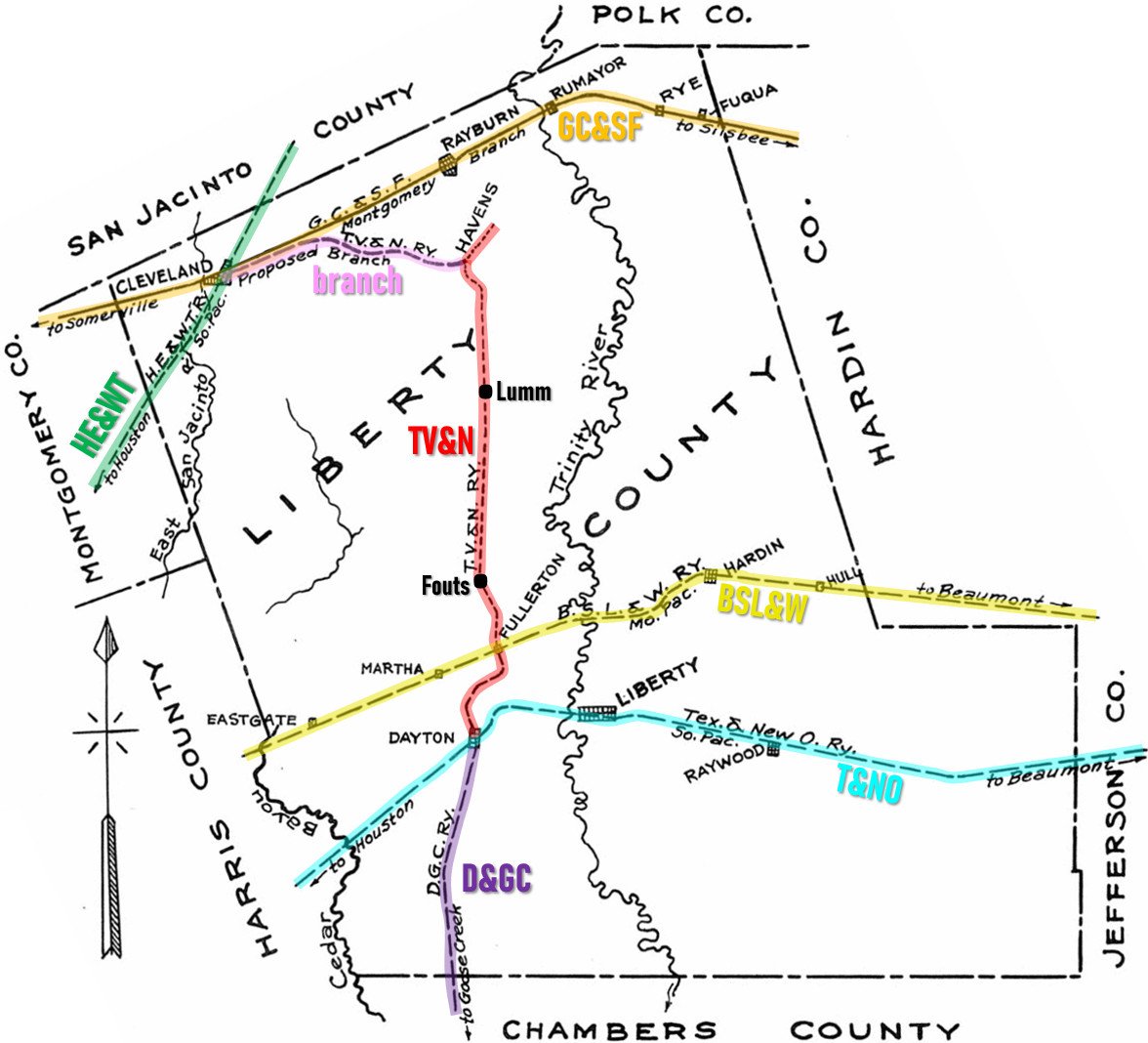

Texas Railroad History - Tower 110 (Dayton) and Tower 148 (Fullerton)

Two Trunk Line Crossings of the

Trinity Valley & Northern Railway near Dayton

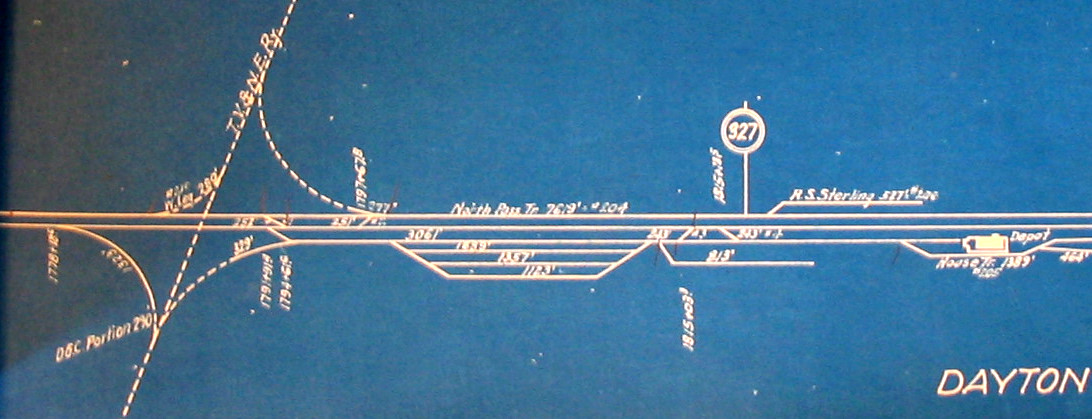

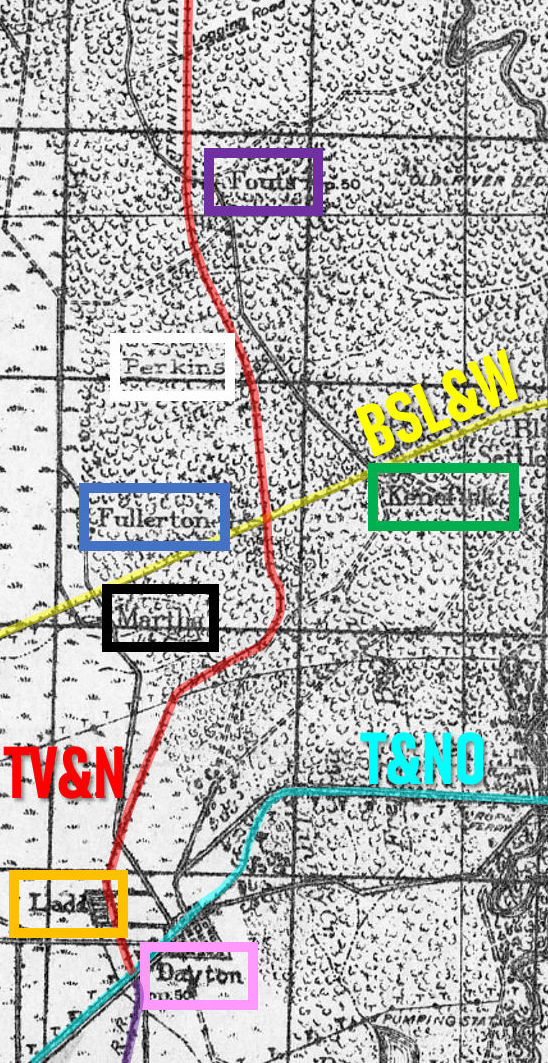

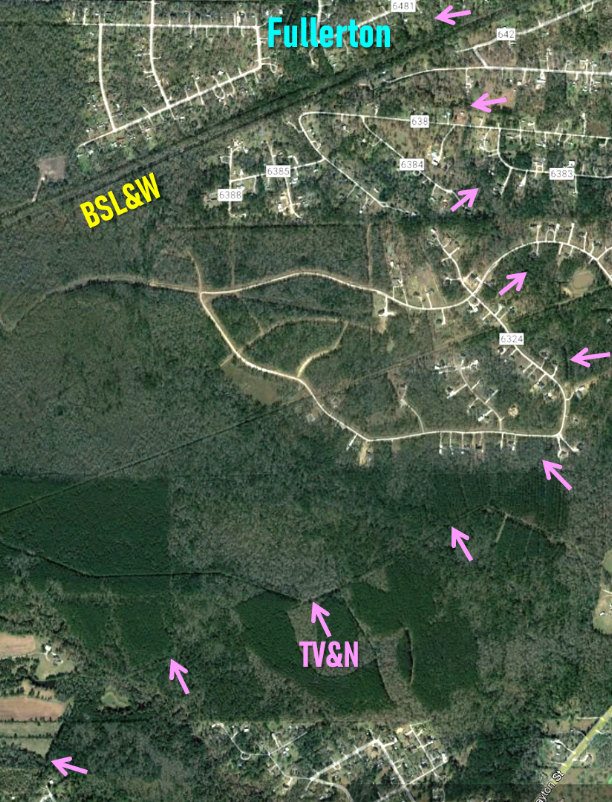

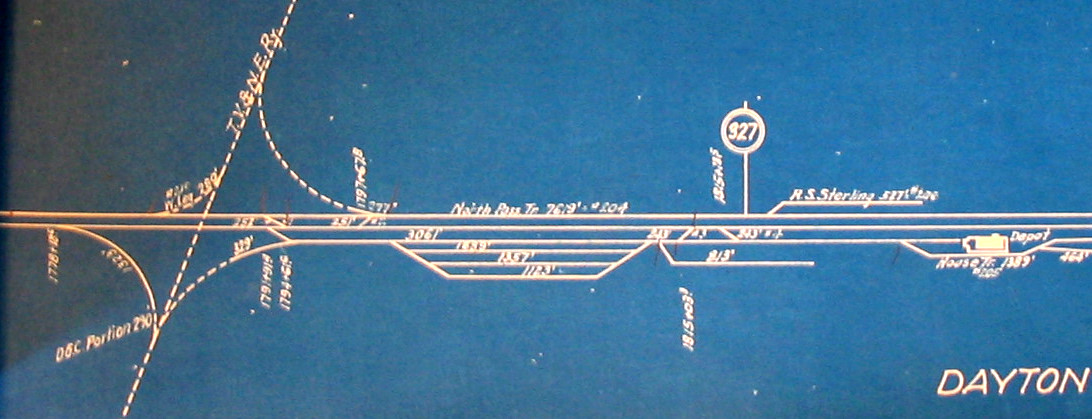

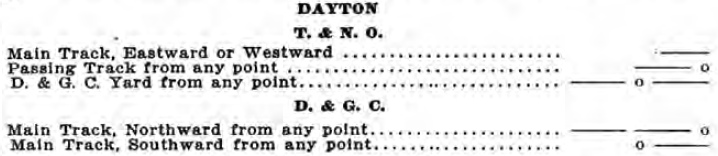

Above: This undated

(c.1920) linen track chart (collection of Bruce Blalock, Jim King photo, 2008) shows the main line of the Texas

& New Orleans Railway running generally east/west through Dayton. The Tower 110 junction west of the yard had Trinity Valley & Northern

rails going north and Dayton & Goose Creek rails going south, with connecting

tracks in all four quadrants. A drawing in the interlocker archives

of the Railroad Commission of Texas (maintained at

DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University) shows Tower 110 in the

southeast quadrant; the nearby connecting track was behind the tower. The T&NO

main line had two tracks, hence the abandonment of the tower in March, 1927

resulted in the removal of two diamonds, but the tracks in all directions

remained in place. The track to the north was abandoned c.1933, but the one to the south remains intact today as do both of the main line

tracks.

West of the town of Liberty across the Trinity

River, the community of West Liberty morphed into the town of Dayton ("Day Town"),

named for land owner, I. C. Day. By 1860, it was known as Dayton Station

on the Texas & New Orleans (T&NO) Railroad

between Houston and Beaumont.

The railroad had been chartered by a lumber company in 1856 for the purpose of connecting southeast

Texas with the port of Galveston. Three years later, the vision shifted toward establishing a rail line between Houston and New

Orleans. By 1860, tracks had been laid between Houston and

Orange, and as the Civil War commenced, the T&NO

briefly became a military supply line. The condition of the tracks deteriorated

quickly, and in the post-war years, there was only intermittent service on short

track segments. Eventually, the line was rehabilitated and reconstituted into a

new company under the T&NO name. The first post-war train between Houston and

Orange operated in November, 1876. In 1880, the T&NO commenced scheduled service

between Houston and New Orleans, making it attractive to Southern Pacific (SP).

SP was assembling a southern transcontinental route out of California, and it

purchased the

T&NO c.1881 to cover the segment between Houston and New Orleans. In the

late 1920s, T&NO became

the primary operating company into which SP's lines in Louisiana and Texas were

leased (1927) and then merged (1934.) With a main line transcontinental railroad

passing through town, Dayton prospered with commerce focused on agriculture

(mostly cotton and rice), oil production and lumber.

The Dayton Lumber

Company opened a sawmill at Ladd in 1906, a mile northwest of Dayton. To access its timber,

the company built tram roads into the nearby forests and immediately established the Trinity Valley & Northern

(TV&N) Railway as a tap line. A tap line was a

chartered and incorporated common carrier railroad owned by a lumber

company (and/or its closely related interests, e.g. management investors.) Tap

lines moved

logs inbound to the mill and wood products outbound to interchanges with

trunk line railroads. As common carriers, tap lines were allowed to operate as

regular railroads by charging the public for carrying passengers, packages, merchant freight,

etc., and

they could sign contracts to transport mail. Lumber trams provided

plant services to assist in lumber production whereas tap lines sold

transportation services to the public. This incentivized lumber

companies to create tap lines into which they would transfer portions of their tram operations, and they would do so for

debt rather than cash. The debt accounts would be repaid by profits

from tap line operations. As common carriers, tap lines also could receive

income from trunk lines through division rates (a percentage of the

total price paid by the end recipient of a shipment.) With lumber company and

tap line ownership often overlapping 90% or more, the entire enterprise

(lumber company plus tap line) would realize increased revenue compared to

simply selling lumber products.

|

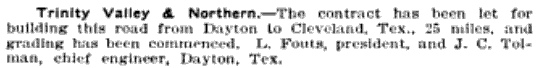

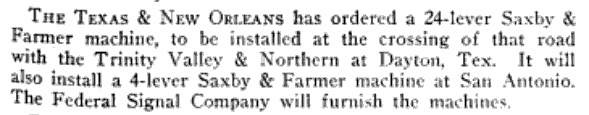

Left: The

Railway Age edition of June 29,

1906 carried this item regarding the contract (presumably with Dayton

Lumber Co.) to build the TV&N from

Dayton to Cleveland. That Cleveland was

listed in the charter as the TV&N's destination became potentially

valuable twenty years later. |

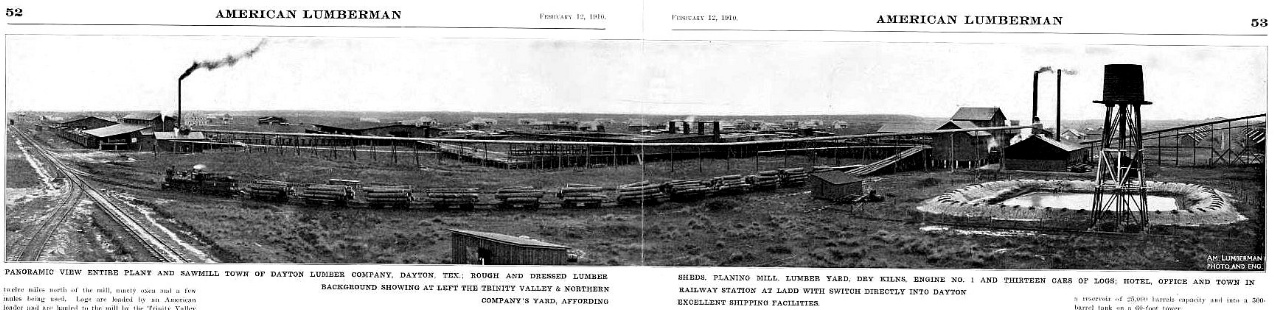

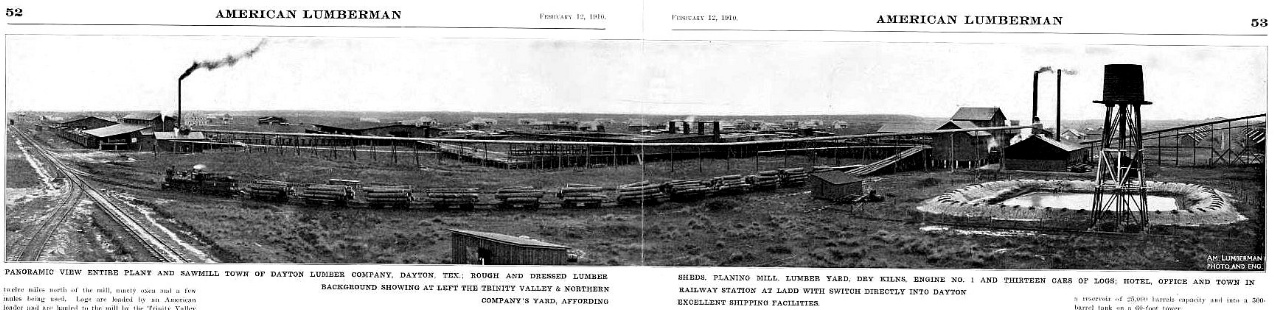

Above: An article in the

February 12, 1910 edition of American

Lumberman discussing the Dayton Lumber Co. notes that it had begun

construction of its sawmill in December, 1905 and had begun sawing logs in July,

1906. For this photograph, the barely legible

caption reads: "Panoramic view entire plant and sawmill town of Dayton

Lumber Company, Dayton, Tex.; rough and dressed lumber sheds, planing mill,

lumber yard, dry kilns, engine No. 1, and thirteen cars of logs; hotel, office

and town in background showing at left the Trinity Valley & Northern Railway

station at Ladd with switch directly into Dayton company's yard, affording

excellent shipping facilities."

In 1909, the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) began

an investigation into more than one hundred tap line railroads

in Texas, Arkansas, Louisiana and Mississippi to determine whether they were

complying with their common carrier obligations, specifically by

posting public tariffs and following them, and by handling passengers and

freight without discrimination. In particular, this required tap lines to charge

their lumber companies to move logs and finished products just as they would

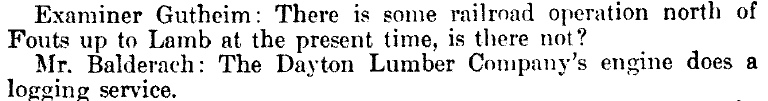

charge any other sawmill. A hearing before

ICC examiners was held in St. Louis on January 23, 1911 at which the TV&N's

auditor, J. J. Balderach, was questioned. The

hearing transcript provides interesting details of the TV&N's history and

operations.

Since the ICC was trying to determine whether the TV&N

qualified as a bona fide common carrier, they eventually asked an obvious

question: Had the Railroad Commission of Texas (RCT) granted common carrier

status to the TV&N? RCT had been created by law in 1891, and from the outset

it had occasionally granted or denied common carrier status to railroads

in response to applications requesting such declaration. Recently, RCT had begun to

question their own authority to make such decisions, and their policy changed as

they considered TV&N's application. RCT's concern was based

on the fact that railroad charters were actual state laws, passed in the Texas

Legislature and signed by the Governor. Railroad companies with

state charters also subjected themselves to a myriad of state laws that governed how

railroads operated, including common carrier obligations. Railroads

were also subject to any

special provisions that might have been included in the laws establishing their charters. RCT was bound

by state law just as much as the railroads, and nothing in RCT's enabling

legislation mentioned the power to determine common carrier status. Thus its

Commissioners

had begun to question whether such declarations were legally ultra

vires ("beyond the powers").

|

Mr. Balderach responded to the ICC examiner's question by reading

an order received in response to TV&N's 1909 application to RCT

requesting a common carrier declaration. Early in

the order, RCT succinctly spells out their revised policy (which had garnered

two votes of the three-person Commission):

The Railroad Commission is given no

authority to determine when railroad companies are common carriers. On the

contrary, the law itself fixes the status of such companies, and does this

absolutely without reference to the judgment or opinion of the Commission. Every

railroad company organized under the laws of Texas has the right to construct

and operate a railroad and are declared to be public highways and all railroad

companies common carriers. A railroad company having a Texas charter and owning

a Texas line is a common carrier by force of the statute, and it is its duty to

operate its road as a common carrier, complying with the laws of the State

regulating such carriers, and obeying and conforming to the authorized rates,

rules and regulations of the State Railroad Commission.

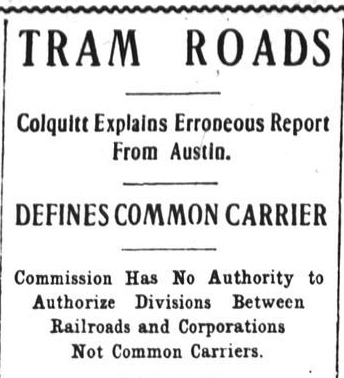

Left: It was

the TV&N's request for common carrier declaration that triggered the change in policy that had been

contemplated by two of the Commissioners. This was big news, and RCT's order

to TV&N was printed in the Houston Post

of June 26, 1909. It had been included in a letter to the newspaper from Commissioner

O. B. Colquitt (who would be elected Governor in 1910)

wherein Colquitt took issue with a report out of Austin claiming that RCT had

made a "...ruling permitting tram roads to become common carriers on the

filing of their charters." Colquitt explained that the erroneous article

"...grew out of a misunderstanding on the part of the reporter on the

meaning of what was done and said." He proceeded to cite various

obligations of common carrier passenger services that were beyond the

means of a typical tram road. These included running a passenger train

over the entire line at least daily (except Sunday), providing

comfortable "heated and lighted" passenger depots, and complying with

various crew and service hour laws applicable to passenger trains.

|

Under the new policy, Texas companies chartered by

state law as railroads automatically qualified as common carriers for

intrastate traffic. They could, however, forfeit their charters through judicial

proceedings if they did not comply with the legal obligations inherent to all

Texas railroads. Initially, tap lines had sought RCT's common

carrier blessing because it allowed them to derive revenue from moving

passengers and freight beyond that of the lumber company, and because it lent credibility to their efforts to seek

division rates from the ICC for

interstate traffic (where RCT had no jurisdiction.)

Under the new policy, tap lines in Texas could begin providing transportation

services to the public without the need for RCT's blessing and they could

request ICC approval for division rates. They could

not, however, establish division rates for intrastate

traffic without permission as such rate-setting was exclusively

within RCT's purview. In the Houston Post

article referenced above, the bottom sub-headline asserts that to whatever

extent RCT had ever authorized division rates between trunk line railroads and

lumber trams (or other private rail lines, e.g. sugar

plantations), those days were over.

The ICC ruling was issued in April and May, 1912,

presenting their analysis of each railroad and their findings that thirty-six of

them did not qualify as common carriers. In its

summary ruling (courtesy Texas Transportation

Archive) the ICC did not object to the TV&N's common carrier

claim, but it did set a limit of one cent per hundred pounds that the TV&N could

receive from a trunk line on interchanged freight. Collectively, the railroads

appealed to the Supreme Court, which remanded the case to the ICC for revision

in light of legal standards made plain by the Court. The initial ICC ruling had

in most cases concluded that a tap line converted from long-existing tram lines and

still largely owned by the same lumber company was per se

not a common carrier (perhaps favoring the

TV&N, which had been chartered as soon as the lumber company began sawing logs.) The Supreme Court overruled the ICC, requiring a

substantially greater and individualized inquiry into each tap line's

operations. Industry observers viewed it as a loss for the ICC, but ultimately,

the most deficient tap lines either increased their compliance with ICC

regulations or reverted

to tram status. In response to the remand, the ICC

began to focus on establishing a settled regulatory environment in which tap

lines had clear rules under which they could operate.

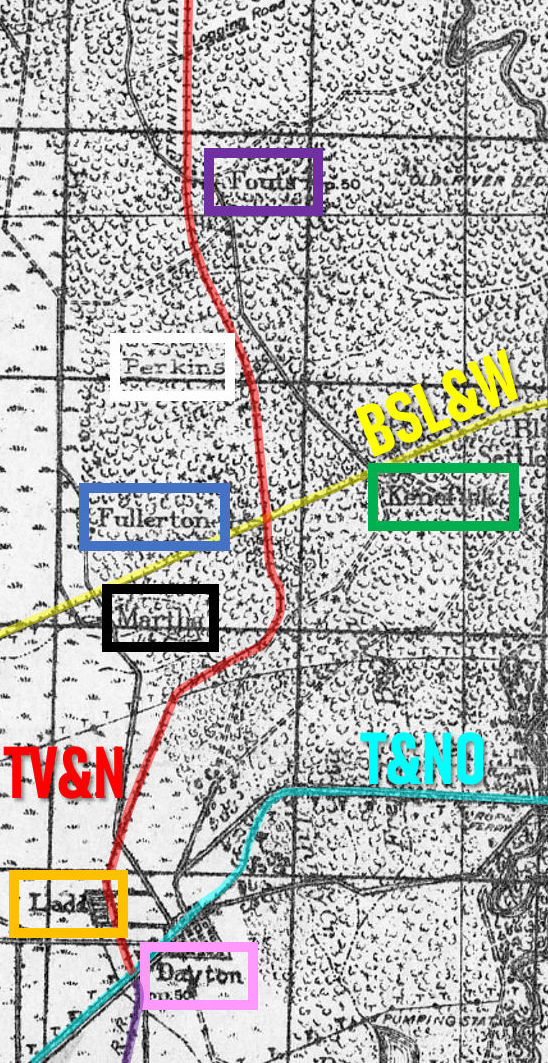

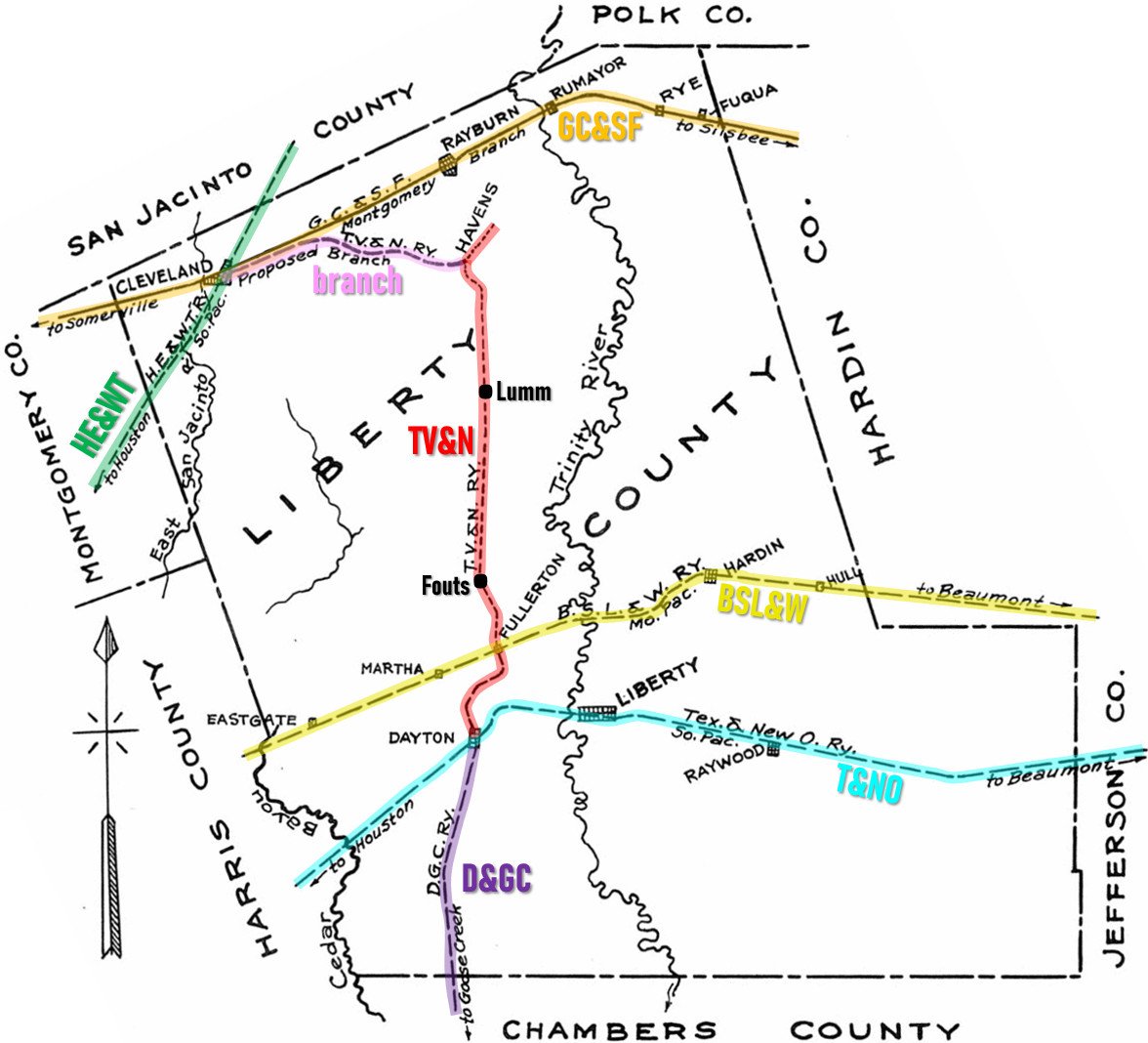

|

Left:

This image has been edited from a U. S. Army Corps of Engineers

topographic map and annotated to show the route of the TV&N (red line)

north from Dayton (pink). By the map date of 1922, the TV&N

connected to the Dayton & Goose Creek Railway (purple line) on the south

side of the T&NO main line (light blue). The mill at Ladd

(orange) was about a mile northwest of the crossing, and was the

maintenance base for the TV&N. Farther north at Fullerton (blue), the

TV&N crossed the Beaumont, Sour Lake & Western (BSL&W, yellow line), a

component of a large

network known as the Gulf Coast Lines. Whether Fullerton was ever more than a rail junction, it no longer exists. Farther north, the TV&N

passed through Perkins (white) and Fouts (purple). Fouts was

a logging camp and Perkins may also have been, but neither survives today. Kenefick

(green) remains a town whereas Martha (black) at the BSL&W crossing of

the main road toward Cleveland

is only a historical location.

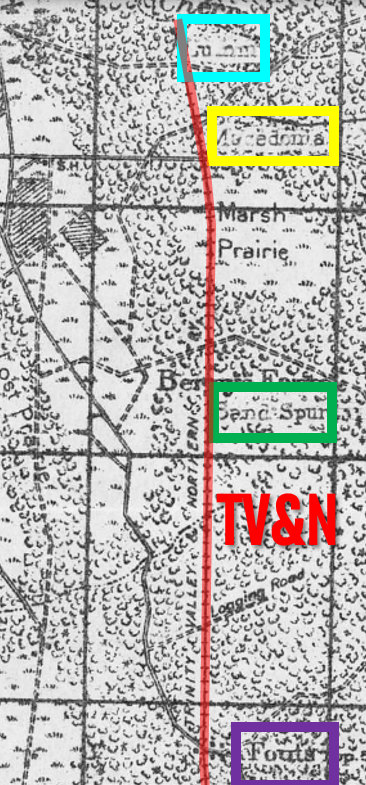

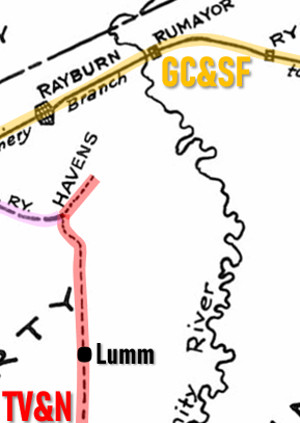

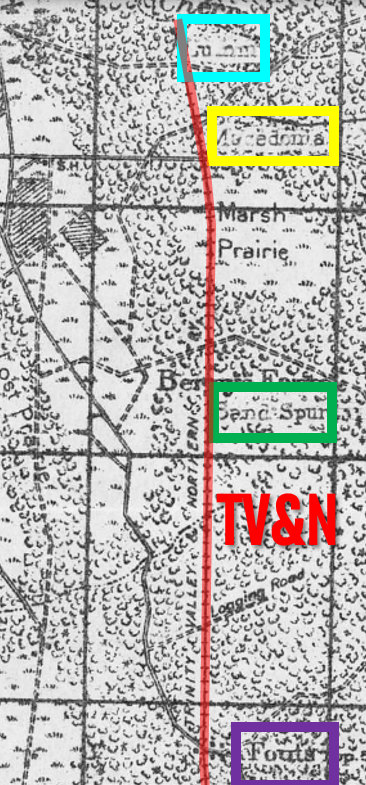

Right: A continuation of the map north of Fouts

shows the TV&N proceeding to Lumm (light blue), the end of the line. Near Lumm,

the TV&N passed through Macedonia (yellow), a settlement founded by a

Chicago syndicate in 1914 as a community of Greek

farmers to raise vegetable crops for market. The community foundered and

lost its Post Office in 1922. Sand Spur (green) appears on a 1923 TV&N

passenger service timetable; it may have been a logging camp but no

longer exists. The communities of Macedonia and Lumm did not survive the

abandonment of the TV&N in 1933.

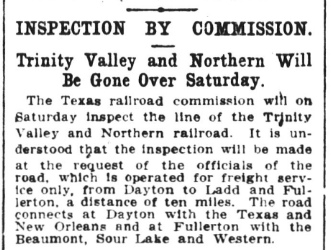

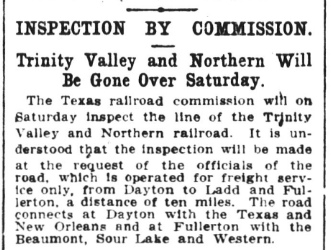

Below Right: In 1909 when TV&N issued its

request to RCT for a declaration of common carrier status, RCT responded

by scheduling an inspection. This was standard procedure and

the decision by the two Commissioners to change the policy regarding

common carrier declarations had not yet been made. The

Houston Post of Friday, May 7, 1909

carried this news item noting that the inspection would take place the

following day, and presumably it did. Seven weeks later, the

Houston Post would carry the

article in which Commissioner Colquitt's letter to TV&N was printed,

announcing RCT's position that such declarations were not necessary (and

never had been) because all chartered railroads in Texas held the legal

obligation to function as common carriers. |

|

At Fullerton, the TV&N

crossed the Beaumont, Sour Lake & Western (BSL&W), a railroad founded in 1904 to

bring oil into Beaumont from the Sour Lake field. By 1905, its line to Beaumont from

Grayburg (about thirty miles east of Fullerton) had

become a tempting target for B. F. Yoakum, a native Texan with a long history in

Texas railroading who had become Chairman of the St. Louis - San Francisco

("Frisco") Railway. Yoakum wanted to compete with SP along the Gulf

coast by establishing a rail network centered on Houston,

an enterprise he called the Gulf Coast Lines (GCL). Yoakum assembled

the GCL by

chartering, building and buying railroads as necessary to connect Brownsville

with New Orleans. The St. Louis Trust Co. provided the financing for the GCL

resulting in an unusual situation; its individual railroads were

managed by Yoakum and his team of Frisco executives, but the Frisco corporation

did not own the GCL. It was essentially a marketing and operations consortium

with Yoakum calling the shots. The GCL's railroads were owned individually

through a syndicate backed by the St. Louis Trust Co. The BSL&W's Beaumont - Grayburg tracks and its Texas railroad charter gave Yoakum a head start on

building the connection his GCL needed between Beaumont and Houston. Yoakum acquired

control of the BSL&W in 1905 and extended it west to Houston, passing

through Fullerton c.1907-08. Whether the TV&N or BSL&W arrived there first is

undetermined, but they were close in time. During the Frisco's 1914

receivership, the GCL continued to operate, but its railroads were reorganized

under an independent corporation, the New Orleans, Texas & Mexico Railway,

created to provide executive-level governance.

Fullerton was named for S.

H. Fullerton, a well known investor and business executive of St. Louis who

probably had some (undetermined) connection with the Frisco and/or the

St. Louis Trust Co. Fullerton had large investments in lumber, coal and

railroads, and he owned fifty shares of TV&N stock. Though it was a small

investment, Fullerton was sufficiently interested in the TV&N to be present at

the ICC hearing held in St. Louis in January, 1911. As the ICC examiner probed

Mr. Balderach on whether Mr. Fullerton or any of his companies held an ownership

share of the Dayton Lumber Co., someone interjected "Mr. Fullerton is here

and he can tell you."

|

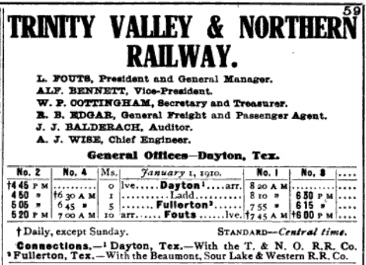

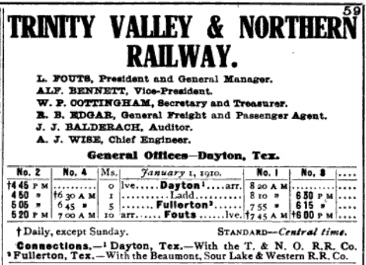

Left: This TV&N

timetable from the 1910 edition of

The Official Guide of the Railways and Steam

Navigation shows passenger service into Dayton at 8:20 am

with a footnote regarding the T&NO connection, presumably made at the

T&NO depot.

A

Houston Post article on September 1,

1910 also mentions the TV&N "...connecting at Dayton with Southern

Pacific trains." The clear implication from the timetable and the

article is that in 1910, the TV&N had a crossing of the T&NO main line

for the purpose of reaching the Dayton passenger depot on the south side of the tracks. The ICC

Valuation Report for the TV&N (as of 1919) lists only "rails and fasteners"

under lease from the T&NO; depot access is not mentioned, but it might

have been granted without a lease. [The decision to lease rails and

spikes from the T&NO benefitted both railroads: the T&NO, by employing a

relatively small amount of its excess rail inventory to help the TV&N

generate valuable outgoing freight interchanges, and the TV&N, because

leasing was less expensive.] The main line crossing depicted on the

linen track chart (top of page) is not known to have existed until

construction of the Dayton & Goose Creek railroad and the commissioning

of Tower 110 in 1918. If an earlier uncontrolled crossing existed for

depot access, it would tend to explain why RCT lists the T&NO and TV&N

as the only railroads involved with Tower 110. But if the TV&N did build

across the main line to reach the T&NO depot c.1910, the connection does

not appear to have survived the implementation of the Tower 110

crossing. The linen track chart does not show a direct connection,

although it was still feasible to reach the depot using reverse moves on

the D&GC main line and connector. |

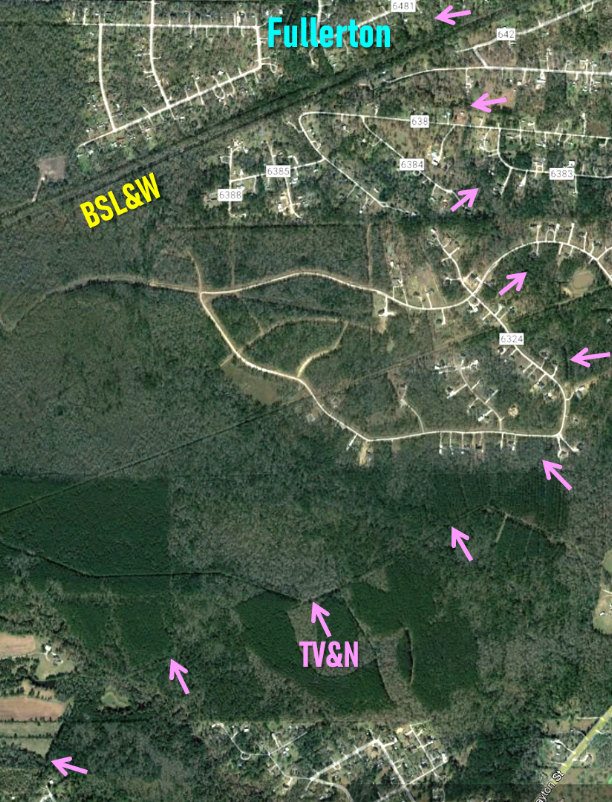

Above Left: In the vicinity

of Dayton north of Farm Rd 1960, Waco St. sits atop the TV&N right-of-way past the mill site at Ladd

to the end of pavement. The right-of-way continues another half mile where it turns northeast to cross State Highway 321 onto Tram Rd. After another half mile,

Tram Rd. ends but the TV&N right-of-way remains visible into the woods.

Above Center: The right-of-way

continues on the 27-degree Tram Rd. alignment into the woods and curves eastward

onto a 68 degree heading for 1.4 miles. It then curves

north to become occupied by 600 ft. of County Road 6324 in a residential area.

From there, it curves slightly west and takes a generally north-northwest

heading following the Bowie Creek drainage. It crosses the former BSL&W tracks just beyond the west end

"loop" of Parker Loop Rd.

(County Rd. 642.) Fullerton is no longer referenced

on maps, if it ever was; the vicinity is now a rural residential area west of Kenefick.

Above Right: About 200

yards north of the BSL&W crossing, the TV&N right-of-way becomes occupied by

County Road 6473 running due north for three quarters of a mile to its

intersection with Cumberland Rd. The road ends but the right-of-way continues

due north for another half-mile and then begins

a very long radius curve over the next mile where it assumes a north-northwest

333-degree heading. The alignment shifts to a 340-degree heading for 0.3 miles and

then almost due north for 0.8 miles to reach Farm Rd 1008 where Fouts was

located.

The TV&N's course

beyond Fouts was essentially due north. The TV&N opened the line to Lumm in

1911, but testimony at the ICC hearing early that year revealed that the Dayton

Lumber Co. had already been operating along the right-of-way for at least a

year, most likely using primitive roadbeds and temporary rails for hauling logs to Fouts

to be interchanged with the TV&N.

The tram tracks to Lumm were upgraded in sections by the lumber company to

the TV&N's standards and the sale was conveyed by adding to the debt account. Between Macedonia and Lumm, the grade

ran directly beside (west of) County Road 2309, but elsewhere, only a few dirt

road segments follow the route. The right-of-way between Fouts and Lumm is readily apparent on

satellite imagery, and it noticeably extends north of Lumm a few miles, crossing

State Highway 105 and eventually becoming occupied by County Road 2185. This is in the direction of Lamb, a station on the Santa Fe

line (now called Hightower) east of Cleveland to which the TV&N had

completed a preliminary survey according to Mr. Balderach's testimony.

Above: Google Street View

provides glimpses of the tram line crossing of TX 105 looking south (left)

and north (right). Although

Mr. Balderach's testimony states that a survey to Lamb had been performed, it is

likely that the actual extension of the tram line north of Lumm -- which

produced this TX 105 crossing -- was done by the South Texas Hardwood Co. in the

1920s.

In

1912, Dayton Lumber Co. defaulted on loans, resulting in a takeover by a group

of creditors. The creditors continued to operate the mill at Ladd, changing its

name to Dayton Mills in 1915. Whether Ross S. Sterling, one of the founders of

the Dayton Lumber Company (and the TV&N) was still involved is undetermined, but

if so, he was unlikely to be paying much attention. Sterling was surely focused

on the oil company he and three others had founded in 1911, Humble Oil Co., with

Sterling as President. Five years later, the Goose Creek oil field south of

Dayton was proven with a 10,000 barrel-per-day well in August, 1916. This

undoubtedly played a role in Sterling's decision to have Humble Oil build a major refinery

near the oil field, along the Upper San Jacinto Bay outlet of the Houston Ship

Channel which had opened officially in 1914.

As construction of the refinery commenced, the company changed its name to

Humble Oil and Refining Co.

To support building the refinery and

shipping its products, plus the need to ship oil directly from the field to

other refineries, Sterling personally founded (and owned virtually all of) the

Dayton and Goose Creek (D&GC) Railway on July 24, 1917. Important though it was,

founding the D&GC was not the

peak of Sterling's career. Sterling sold out of Humble Oil (long before it

became Exxon), went into the real estate business, bought and merged the

Houston Post and

Houston Dispatch, became Chairman of the Texas

Highway Commission, was elected Governor of Texas in

1930 (serving from January, 1931 to January, 1933), founded an investment

company and another oil company, became President of American Maid Flour Mills,

and was named Chairman of the Houston National Bank. He used his spare time (?)

focusing on philanthropy.

The D&GC promptly began construction of a

23-mile line from Dayton south to the Goose Creek field. Carrying oil and

refined products to both the T&NO and BSL&W connections at Dayton and Fullerton,

respectively, was an important aspect of the plan. Reaching Fullerton required

the D&GC and the TV&N to connect at Dayton, which meant that a crossing of the

T&NO was necessary. To whatever extent a crossing may have existed for TV&N

passenger trains to reach the T&NO depot, it was clear that it would need to be

rebuilt to account for heavier and longer trains, additional connecting tracks,

an interlocking tower, and a wye north of the T&NO so that D&GC locomotives

could be positioned properly when exchanging railcars. The interlocking plant

was ordered by T&NO in November, 1917 and service to Goose Creek commenced May

1, 1918. Seven months later, Tower 110 was commissioned by RCT to control the

Dayton crossing. By 1919, the D&GC had been extended 2.5 miles farther south to

serve the Humble Oil refinery under construction at

Baytown.

|

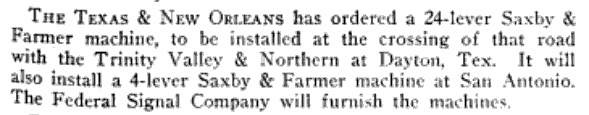

Left:

Tower 110's 24-lever mechanical plant built by Saxby & Farmer was ordered by

T&NO in the fall of 1917. It was commissioned December 18, 1918 and appeared

in RCT's annual list of active interlockers dated December 31, 1918. The

list shows Tower 110 having 18

functions, a size indicating control of connecting track switches and signals. Like this article from the November, 1917 issue of

Railway Signal Engineer, RCT lists the TV&N as the railroad that crossed the T&NO at Tower 110. |

RCT records show that T&NO staffed Tower 110's

operations (and almost certainly its maintenance as well.) No photo of Tower 110

has been found, and it does not appear on Sanborn Fire Insurance maps of Dayton; it was too far west.

The ICC's Valuation Report for the D&GC

states that the tower was owned by T&NO and leased to D&GC for 50% of the cost

of operation. RCT interlocking records reflect track ownership (TV&N) at the

crossing, but the ICC reports reflect operations, i.e. the D&GC and T&NO were

splitting the sustaining costs for the interlocking since they were the operational

participants, even though D&GC was not listed in annual RCT interlocker

reports.

|

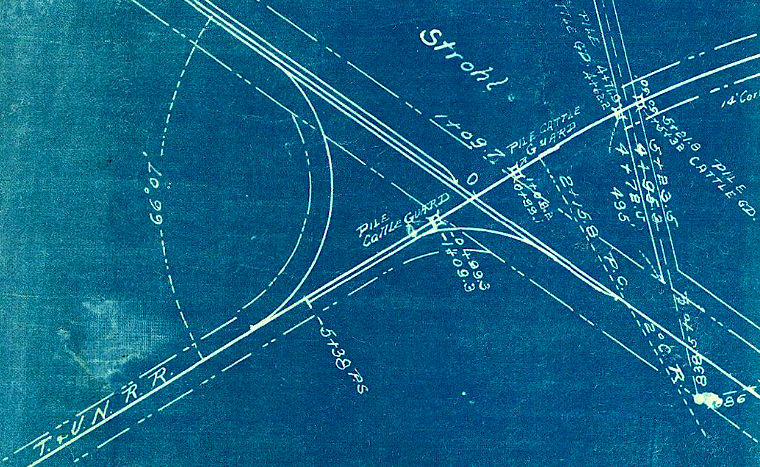

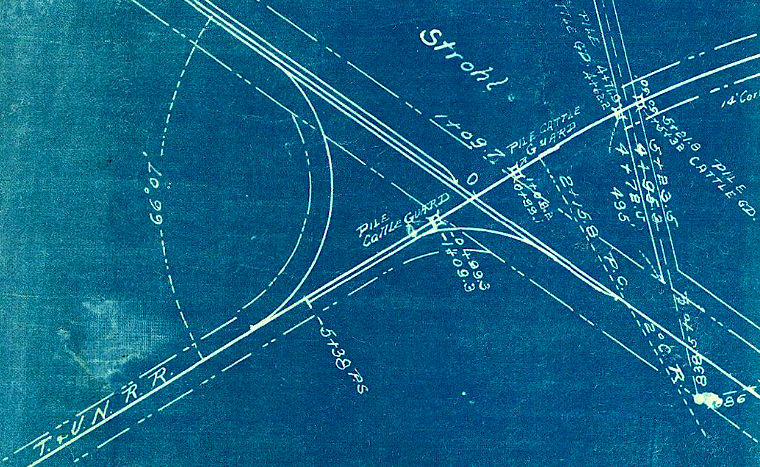

Left: This snippet

from a 1917 D&GC map (courtesy Texas General Land Office) shows

the initial plan for the Tower 110 crossing at Dayton (incorporating

four "pile cattle guards" !) The map was drawn with the intent of having

the D&GC tracks generally depicted horizontally so that the connections

to companion maps would be along the right edge of the drawing.

This resulted with North being toward the lower left corner (where

"T&VN" is mistakenly labeled instead of "TV&N" ). The map shows the D&GC

without connecting tracks to the T&NO; its only connection is directly

to the TV&N. This seems odd, but by the date of the ICC's preliminary

valuation for the D&GC (December 31, 1920), the D&GC and T&NO had built

1.5 miles of "...yard tracks and sidings at Dayton." These

tracks were "owned

equally and used jointly..." and presumably included the tracks east and west of the D&GC that appear on the

linen track chart. The oval directly above the two crossing diamonds (in what is actually the southeast

quadrant) likely represents the planned interlocking that became Tower

110.

A 1920 track chart shows a "Dayton & Goose Creek Wye" north of Tower

110, going east off the TV&N main line a short distance south of Ladd.

This suggests that a D&GC locomotive would bring its oil train through

Tower 110, decouple from the train and move onto the wye track. A TV&N

locomotive would back down from Ladd to connect to the train and take it

north to Fullerton while the D&GC locomotive turned around using the wye

and either waited for the return train or went back south to Baytown. |

|

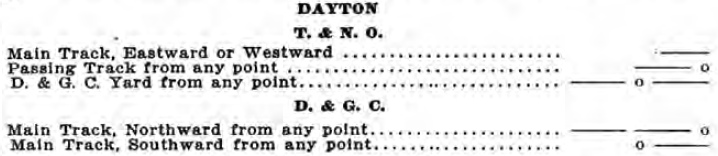

Right:

SP's Beaumont -

Galveston Division Timetable

of December 5, 1920 shows whistle codes for T&NO and D&GC locomotives to

request tower operators to set switches and signals for movements. The

implication is that the tower was manned and most likely two stories. It was near a busy T&NO yard and

had codes for both railroads; operators would need the elevation

for good visibility in all directions. An earlier March 1, 1920 T&NO timetable

lists the TV&N as the other railroad, the only TV&N code governs main track movements, and the

third T&NO code is for "West End Stock Pen Track". Why did

the whistle codes change between March and December? Perhaps the D&GC

connectors were built in this timeframe. |

|

There is no doubt that T&NO built Tower 110, hence it

undoubtedly resembled other SP towers in Texas, e.g.

Tower 26 and Tower 115, which opened,

respectively, well

before and well after Tower 110. All SP towers in Texas were two stories and all carried an

architectural

resemblance. Since the construction of the D&GC created the need for the

interlocker, D&GC (perhaps

through TV&N's books) would have paid the entire capital cost of the tower (it

was a post-1901 crossing; capital expenses for interlockers at pre-1901 crossings were shared

equally.)

|

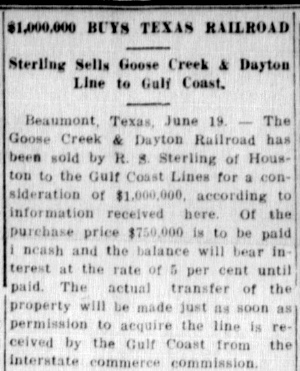

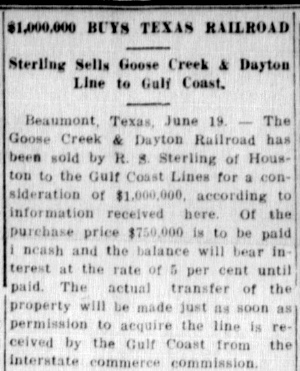

Left: In June,

1922, Sterling sold the D&GC for a million dollars to the GCL. (Bay City Daily Tribune,

June 19, 1922)

The GCL operated independently after

the corporate entity was established during the Frisco's receivership.

When D&GC began shipping oil through the Fullerton connection in

late 1918,

the GCL undoubtedly realized rather quickly that they would come out ahead if they simply acquired

the D&GC. Although shares of the BSL&W's

revenue for each oil shipment through Fullerton were taken by both TV&N

and D&GC based on division rates, TV&N's share was tiny whereas D&GC

originated the shipments and had a longer haul. D&GC was, however,

only a small part of Sterling's wealth and he had larger endeavors on

which to focus. His decision to sell may also have been impacted

by the Transportation Act of 1920 and the lawsuit he initiated against

it. The Act terminated the U. S. Railroad Administration's control

of the railroads that had been in place during the World War, but it contained a

controversial provision, the Recapture Clause, authorizing the ICC to

set a fair rate of return for railroads and mandating that the ICC

"recapture" half of any excess profits. As Time

magazine explained (January 21, 1924)... "The moneys received by the

Government under this provision of the Act are placed in a fund from which loans

are made and equipment leased to railways, the purpose being to bolster up the

weaker roads with part of the excess earnings of the stronger roads."

The

D&GC line to Baytown had been so profitable that it had nearly paid for

itself in only a few years. As a result, D&GC was

required to remit "excess profits" earned in 1921 (and in

future years) to the Federal

government. D&GC sued in Federal Court for the Eastern District of

Texas claiming that the recapture was an unconstitutional taking of

private property (the "excess profit") in violation of the Fifth Amendment.

The D&GC lawsuit was joined by nineteen other railroads and taken all

the way to the U. S. Supreme Court. The Court ruled unanimously against

the railroads on January 7, 1924. |

Long before the Supreme Court ruling, Sterling had

received more bad news -- the ICC had rejected Sterling's proposed sale to the

GCL. The ICC's rationale was that the price was "greatly

in excess of the value of the physical property involved" and that

the motivation for the high price was simply "to secure a larger

proportion of the traffic". The ICC did not view the price as

reasonable nor the sale to be in the public interest, much to the

surprise of railroad industry observers. Subsequently, the value of the D&GC

physical plant rose substantially. In 1926, Sterling proposed to sell the

D&GC to SP for $900,000 and the ICC approved. SP promptly conveyed

the D&GC to the T&NO and it became fully integrated into T&NO

operations.

With its newly acquired line to Baytown, T&NO could now

prefer its own network for oil and refinery traffic, eliminating the movements through

Fullerton. Since the BSL&W line through Fullerton and the T&NO line through

Dayton both went to Houston and Beaumont, railcars could be transferred to the

BSL&W at those points if necessary rather than Fullerton. This hit the TV&N hard as it had derived steady revenue from carrying

oil shipments on its tracks. With oil traffic no longer moving through

Fullerton, the primary need for Tower 110 was eliminated. RCT files show that

the tower was authorized for abandonment on October 18, 1926, and was actually

removed from service on March 18, 1927. It seems likely that T&NO simply removed

the TV&N diamonds, retaining the connecting tracks while closing the tower.

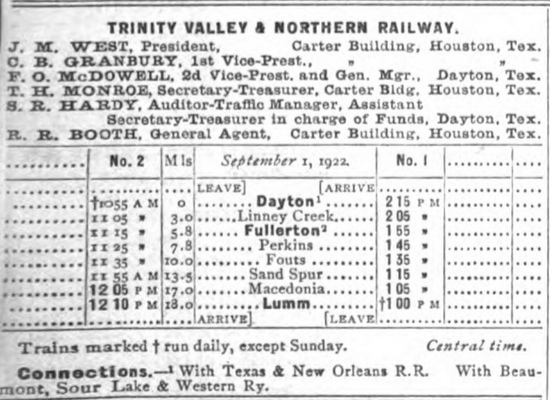

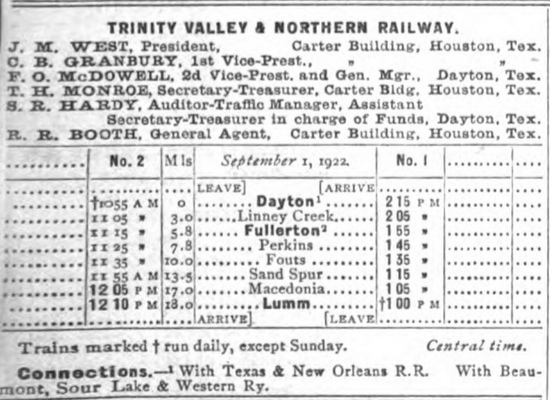

Right:

The 1923 edition of the Official Guide of

Railways and Steam Navigation included this timetable for

TV&N passenger operations effective September 1, 1922. The mill at Ladd

no longer shows a station, although it is likely that the train

overnighted at Ladd. Service commenced at Dayton at 10:55 am and went as

far north as Lumm -- the end of the line for the TV&N. The entire

round-trip was only once daily, finishing back at Dayton at 2:15 pm.

New stops along the line compared to the 1910 schedule were at Sand

Spur, Macedonia and Lumm, all north of Fouts, and at Perkins and Linney

Creek south of Fouts. The T&NO and BSL&W connections remained listed,

with the connection at Dayton implying that TV&N had some way of

negotiating the crossing at Tower 110 to reach the T&NO depot. This

was prior to the demise of Tower 110 and likely involved one or more

reverse moves. There was a wye near Ladd that may have been used. How the TV&N managed to reach the T&NO depot across Tower 110 for passenger service

is undetermined, but the removal of Tower 110 in 1927 certainly ended

it. |

|

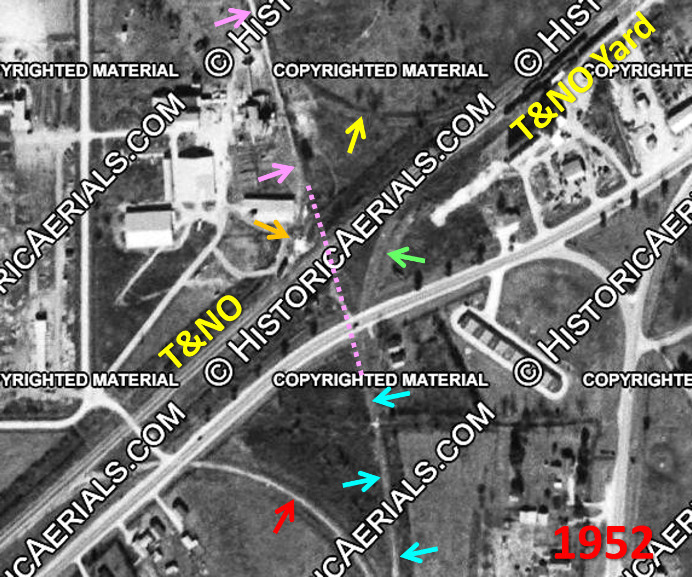

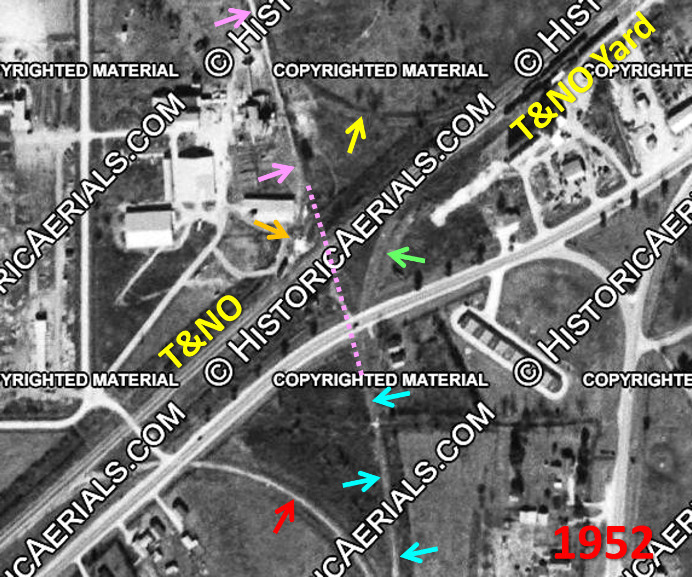

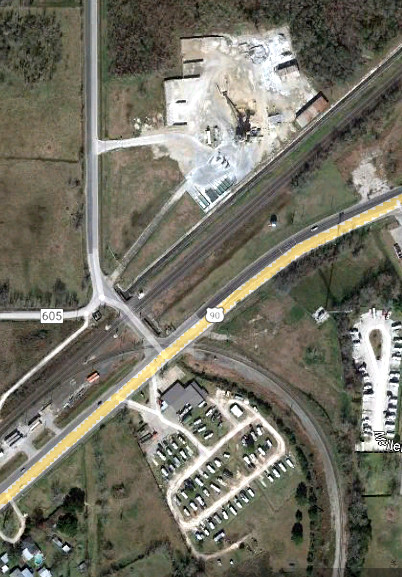

Above Left: A

short section of the former TV&N tracks (pink arrows) may have existed at

the Tower 110 crossing site when this

image from 1952 ((c) historicaerials.com) was captured. If so, then it was

accessed from the T&NO by a northwest quadrant connector (orange arrow.) The

opposite connector (yellow arrow) appears abandoned. The TV&N had crossed over (pink dashes) the T&NO to connect to

the D&GC main line (blue arrows) on the south side. The D&GC east connector (green arrow) led to T&NO's yard and passenger depot. Among all four

quadrants, the southwest connector (red arrow) is the only one that remains in place,

as shown (above right) by this January, 2022 Google Earth image.

Below: A grade-separation project

plan is being developed to eliminate the Waco St. grade crossing of the main line and the US 90 grade crossing of

the southwest connector. (Google Street View, May 2023)

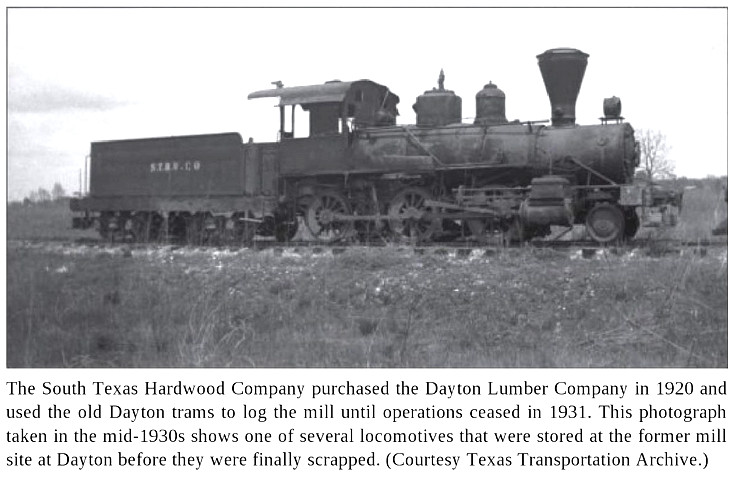

In

January, 1920, Dayton Mills was sold to the South Texas Hardwood (STH) Co., a

company based in Houston with its production done at a contract mill in

Cleveland. STH had acquired rights to approximately 70 million feet of timber in north Liberty County

five miles north of Lumm, a location the company called

Havens (undoubtedly named for STH's principal owner, A. C.

Havens.) The TV&N ended at Lumm and thus did not actually extend as far north

as Havens. Yet, there is a right-of-way clearly visible on satellite imagery extending north from Lumm, crossing over TX 105 (images farther above)

into what should be the vicinity of Havens.

|

|

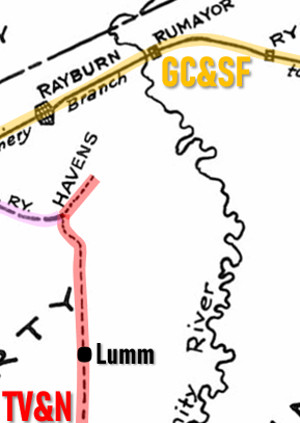

Far Left:

This annotated snippet from a map sketched by the Gulf, Colorado & Santa

Fe (GC&SF) Railway shows the area identified as Havens. The dashed

line (red highlight) running through Lumm to

Havens is indicative of the TV&N because south of Lumm (on the larger map),

it goes to Fullerton and

Dayton.

Near Left:

There is a right-of-way visible on Google Earth satellite imagery that

runs generally north from Lumm (yellow arrows.) North of State Highway

105, the right-of-way eventually becomes County Road 2185 (pink arrows.)

The shape of the right-of-way where it is occupied by County Road 2185

-- a slight west curve followed by a larger east curve followed by a straight section on a

45-degree heading -- generally matches the drawing of Havens' location

on the map. Nearly a decade before the sale to STH, at the January, 1911 tap line hearing before

the ICC examiners, Mr. Balderach had testified that the TV&N had completed a

preliminary survey of a route north from Lumm to Lamb (now Hightower), a

location on the GC&SF. He also stated that Dayton Lumber Company was

operating a tram north of Fouts.

Balderach later stated that the lumber company was not yet operating all

the way to Lamb. Havens was reported to be five miles north of Lumm,

which places it where the big curve is located on County Road 2185. It

was also described as 12 miles southeast of Cleveland, but it's closer to

11 miles due east. There is no obvious visual evidence that a right-of-way ever existed

beyond Havens to Lamb, at least not a direct one. |

As the timber between Dayton and Lumm played out by

the late 1920s, it is likely that the only raw logs being shipped to Ladd were from

STH's harvesting at Havens. Logs would have been carried by tram

rails to Lumm and over the TV&N tracks to Ladd. STH and the TV&N

must have determined that

hauling logs from Havens to Ladd would be less expensive overall if the tracks

between Lumm and Fullerton were returned to tram status. This is inferred from

TV&N's decision to request permission from ICC to abandon the tracks north of

Fullerton. Apparently, no other traffic was being carried on this segment and thus, no

external revenue was being generated by TV&N. Most likely, the logging camp at Fouts was no longer in use;

STH had established camps much closer to Havens. Tram employees were

probably running the logging trains the

entire distance to Ladd, with TV&N simply collecting rights fees (which

effected no net gain to the enterprise as a whole.)

|

Left:

The March 2, 1929 edition of

The Traffic World summarized the ICC

Finance Docket entry on the proposed abandonment of the TV&N between Fullerton and Lumm "due

to line having served purpose of transporting logs." Perhaps "having served"

should be interpreted as "only serving". |

On April 13, 1929, Tower 148, a cabin interlocker

with an 8-function mechanical plant, was commissioned by RCT to begin service at

Fullerton governing the TV&N's crossing of the BSL&W. A mere

three weeks later on May 4, 1929, the ICC

authorized the TV&N to abandon its tracks north of Fullerton. Why would TV&N

(or, for that matter, the ICC) allow a cabin interlocker to be planned for

Fullerton knowing that the abandonment of the tracks north of

there was in progress? The existence of Tower 148 lends credence to the idea that, despite the

abandonment, logging

trains would continue to operate across the BSL&W at Fullerton. The abandonment

between Fullerton and Lumm did not remove the rails; it merely changed how the

tracks were operated and managed, i.e. by a logging company tram line instead of

a common carrier. South of Fullerton, the TV&N continued to operate as a common

carrier, shipping lumber products from the mill at Ladd to its two trunk line

connections (and thus, as a tap line, continuing to receive revenue divisions

from each shipment.) RCT records list the BSL&W and the TV&N as the railroads

responsible for Tower 148, but that did not preclude logging trains from

operating through Fullerton with STH crews and equipment while paying trackage rights fees for the privilege.

|

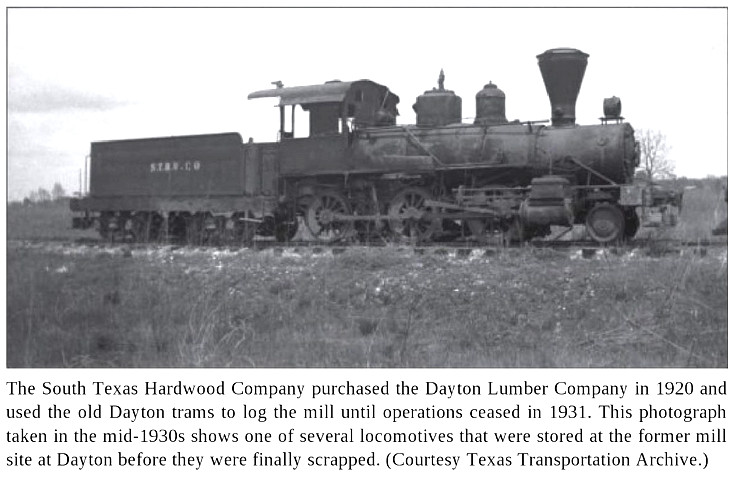

Left:

This image and caption appears in East

Texas Logging Railroads (Arcadia Publishing, 2016) written by

noted Texas rail historian (and well-known musician)

Murry Hammond.

The crossing at Fullerton

had never been interlocked, but it was almost certainly gated, with the gate

lined against the TV&N. TV&N trains had to stop at the diamond to open and close

the gate, but the TV&N operated very few trains overall, so its delays were

inconsequential. The BSL&W had more traffic through Fullerton, and its

trains had to slow to a restricted speed to observe the gate at

Fullerton to determine whether they had to stop. The Kenefick station was

only a little over a mile east of Fullerton, so BSL&W trains would be operating slowly

through Fullerton anyway, approaching or departing Kenefick. For the

BSL&W, the overall impact of the gated crossing at Fullerton had

apparently been insufficient to motivate installation of an interlocker

prior to 1929.

The BSL&W and its affiliated

GCL railroads became owned by

Missouri Pacific (MP) in 1925. For reasons undetermined, MP embarked on

a major push in 1929 to install cabin interlockers throughout the GCL network. In addition to Tower 148 at Fullerton, cabin

interlockers were installed at Edinburg and Edinburg Jct. (Towers

149 and 145), Edcouch (Tower

146), Lantana (Tower 147), Rosita (Tower 151),

Angleton (Tower 154), Grayburg (Tower 155), Allenhurst (Tower 156), Blessing (Tower 157)

and Placedo (Tower 158), all of them in 1929, all

of them cabin interlockers, and all of them at crossings of GCL tracks. There was no special reason to interlock Fullerton in 1929; it

was simply on MP's list. |

A cabin interlocker was an inexpensive way of

controlling a crossing without the need for a manned tower. For Tower 148,

logging trains would stop at Fullerton and a crewmember (or perhaps a STH

employee who had traveled to the crossing ahead of time) would enter the trackside cabin to set

the interlocker controls to signal any approaching BSL&W trains to stop before

reaching the diamond. This would also change the home signal for the logging

train to proceed across the diamond. If a BSL&W train was already too close to

the crossing, the interlocker would prevent changing the signals until after the

BSL&W train had passed. After the logging train had crossed the BSL&W, a

crewmember or employee would reset the controls to signal unrestricted movements

on the BSL&W tracks.

The January, 1929 edition of

Railway Signaling and Communications provided a

list of Automatic Block Signals Contemplated for 1929 in which there

are two entries involving the GCL at Fullerton: "Gulf Coast, Tex. to

Fullerton, 33 mi." and "Fullerton, Tex. to Beaumont, 50 mi."

If block signals were being contemplated by GCL for the entire distance

to Beaumont from

Gulf Coast Junction (where the BSL&W intersected the East Belt in Houston -- see

map at Tower 80), wouldn't one simple

entry in the list, e.g. "Gulf Coast, Tex to Beaumont, 83 mi.", suffice

to convey the block signaling being contemplated? The information was most

likely supplied by the railroad and Tower 148 was installed three months

later, so it's fair to assume that two separate entries of block signals

involving Fullerton was associated with the impending interlocker

installation. The specific implication for whether (and how) the interlocking plant

might

ultimately have been tied into the block signals is unclear. The eight

functions of the

Tower 148 interlocking plant are undetermined but four home signals and

four derails would be a good guess. Distant signals were not needed on

the TV&N -- trains always stopped at Fullerton. Distant signals were

probably not needed on the BSL&W -- trains were operating at restricted

speed into or out of Kenefick.

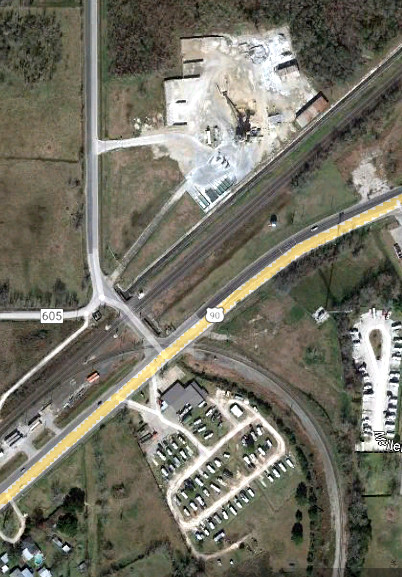

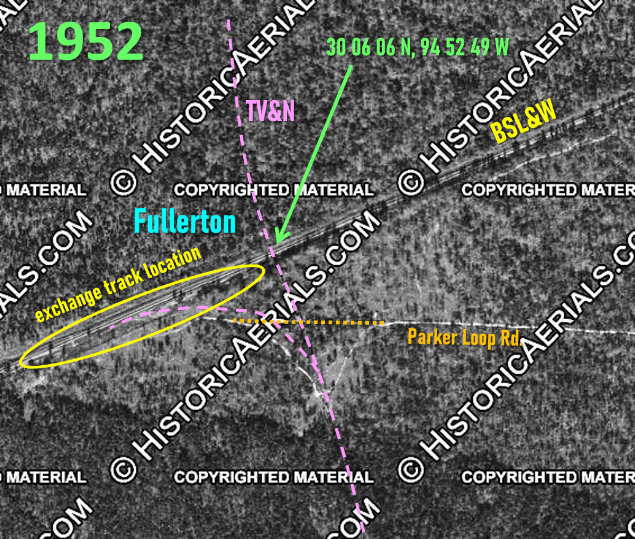

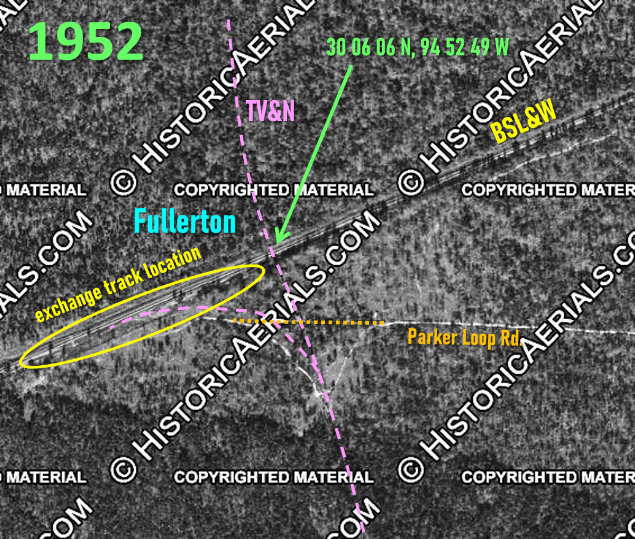

Right: This

annotated 1952 aerial image ((c) historicaerials.com) of the Tower 148 crossing

at Fullerton

shows that there was little left to see some twenty years after

the 1933 abandonment of the TV&N between Dayton and Fullerton. The

siding / exchange track appears to have been west of the diamond on the south side of

the tracks. The visible gravel road is now the far west end of Parker

Loop Rd. It previously curved abruptly south to cross the tracks at a

location where the road could match the elevation of the grade. It

then curved sharply back north to reach the siding and exchange track.

It now continues straight across the former right-of-way and terminates where the exchange tracks and sidings were located.

(A "Bird's Eye View" image of the exchange track area can be seen

here -- be patient; the map loads quickly but the image loads very slowly.) |

|

Within a year after the installation of Tower 148

and the formal abandonment of TV&N's tracks north of Fullerton, STH decided that it needed to dismantle the mill at Ladd and relocate it to

Havens. While this would greatly reduce the time and expense of moving logs to

the mill, it would place the trunk line connections at Fullerton (17 miles) and

Dayton (23 miles) at lengthy distances from the mill. It would also require new

exchange tracks at Fullerton to be built on the north side of the crossing, or

perhaps restructured on the south side since heretofore, all TV&N trains with

products shipped out of the mill had approached Fullerton from the south. To obtain common

carrier divisions on outgoing shipments, the plan would

also require TV&N to reinstate ownership of the tracks between Lumm and

Fullerton, and add ownership of the tram tracks between Havens and Lumm (which

would probably need to be rebuilt to TV&N's specifications for common carrier

use.) Since extensive ICC approvals would be required for this approach, it was

apparently determined to be much less

expensive for STH simply to build a new 12-mile track from Havens to

Cleveland where two trunk line connections were available.

Above: On July 25, 1930, STH applied to the ICC for

permission to build a common carrier line between Cleveland and Havens under the

TV&N charter. Using the TV&N charter would eliminate the need for a

new charter from the Legislature, and it was viable to do so because TV&N's

charter had incorporated permission to build to Cleveland. Connecting at

Cleveland with two trunk lines -- the GC&SF and the Houston East & West Texas (HE&WT) -- would generate division revenue to TV&N for

products shipped from the mill at Havens, but only if the ICC approved

construction of the new line under common carrier "public convenience and

necessity" rules. If the ICC ruled that the new line had no public benefit, then

it could only be built as a private railroad and no division rates would be

available at Cleveland for interstate traffic (nor for intrastate traffic under

RCT's revised policy.) This map (courtesy Texas

Transportation Archive) was produced by the GC&SF in 1930. It was probably created as part of GC&SF's

submission of comments to the ICC in response to the "proposed branch"

On April 16, 1931, the ICC issued a

ruling that rejected STH's

application on the grounds that a rail line between Havens and Cleveland offered

no public benefit. As a result, the mill was not relocated from Ladd to Havens

and no tracks between Cleveland and Havens were ever built. The TV&N shut down

in 1932 and its remaining tracks, Dayton to Fullerton, were abandoned in 1933.

It is not known whether the abandonment of the remainder of the TV&N affected the need for Tower

148 since logging trains might still be crossing at Fullerton to reach the mill at

Ladd, as long as the mill remained open. The Texas Forestry Museum sawmill database indicates that the mill at Ladd

closed in 1934. At that point, if not earlier, Tower 148 could be closed, but

unfortunately, the actual date of its closure has not been determined. The BSL&W

and T&NO tracks remain in use today as main line routes through Fullerton and

Dayton, respectively, both now owned by Union Pacific. Fullerton is simply a

historical location; a town never developed. Dayton has become an exurb of

Houston with about 40,000 residents living within Dayton's Zip code.

Right: SP depot at

Dayton in May, 1980 (C. E. Hunt photo)

The D&GC Valuation Report states that the railroad shared the T&NO's passenger and freight

stations at Dayton by paying 25% of the operating costs. The D&GC

undoubtedly did a brisk business moving Baytown residents and other

refinery visitors and employees to and from Dayton for access to SP's

passenger network. |

|

Traces of the TV&N from Google Street View: at Farm Rd. 1008 near Fouts

facing south (above left)

and north (above right); north

of Fouts at CR 2326 facing south (below left)

and north (below right)

Above Left: The pavement on

Waco St. in Dayton ends but the TV&N right-of-way continues north.

Above Right: A faintly visible

"Road Closed" sign marks the end of Tram Rd. where the TV&N right-of-way

continues into the woods on a northeast heading.

Below Left: Looking north, CR 6473 occupies the TV&N

right-of-way for three-quarters of a mile beginning just north of the Fullerton

crossing. Below Right: At the

north end, CR 6473 tees into Cumberland Rd., but the TV&N right-of-way continues

straight ahead. (Google Street View images)

Above Left: North of TX 105, the right-of-way approaches from the south heading for

the area STH called Havens. It will become County Road 2185 (Palmer Lake Rd.) as it

reaches the camera, which is looking south from FM 2252. Above

Right: Palmer Lake Rd. continues north from its T-intersection

with FM 2252. The dirt road occupies the right-of-way through the "big

curve" (presumably the main site of Havens), but how much farther the tram

right-of-way extended is unknown. (Google Street View)

Below: In contrast to the

TV&N, these two Google Street Views of UP's former D&GC tracks fail to convey

the enormity of the petrochemical industrialization that has occurred between

Dayton and the refinery at Baytown. The refinery is so large that

there is no good way to show the railroad service into the plant.

Left: Looking south from the

Grand Parkway, the Baytown refinery is another 12 miles beyond the Exxon Mobil

chemical plant in the foreground. Right:

This view shows the Shell Oil facility north of the West Winfree Rd. grade crossing in Mont

Belvieu, a community between Dayton and Baytown. (Google Street View)