Texas Railroad History - Tower 191 - Marlin

A Crossing of the Southern Pacific Railroad and the

Missouri Pacific Railroad

|

Left: Rails in

the pavement on Monroe St. help visualize the crossing of the Southern Pacific (SP)

and Missouri Pacific (MP) railroads on the north side of Marlin, a site interlocked as Tower 191

in 1946. This Google Street View from July, 2023 looks southwest along

the former MP right-of-way. The former SP tracks cross at an acute angle, now owned by Union Pacific (UP).

The rails in the pavement indicate a connecting track between the two lines;

a track chart shows it dating to at least 1915.

From Marlin, the

MP and SP lines both went northwest to Waco, but the SP route was

shorter, with fewer grades and curves. In the mid-1960s when SP planned

to abandon their line through Marlin, MP arranged to buy it and

abandon their Marlin-to-Waco tracks instead. This gave MP a shorter and

easier route to navigate into Waco, hence, UP's track has both

SP and MP heritage.

Having acquired the SP tracks to Waco, MP

needed a connecting point in Marlin. Tower 191 could have served that

purpose if a new connector had been built west of SP's tracks,

approximately where the utility pole on the right now stands. Instead,

where the MP and SP tracks approached Marlin from the south, MP built a

0.7-mile connector between them, abandoning its tracks

farther north as SP abandoned its tracks to the south. |

By an act of the Texas Legislature, Falls County was

carved out of Milam and Limestone counties in 1850, named for waterfalls on the

Brazos River which bisects the county. The law specified a settlement west of

the Brazos as the county seat, but a vote of county residents in January, 1851

relocated the seat to Adams east of the Brazos. Two months later, the

county commissioners voted to rename Adams in honor of John Marlin, a landowner

who had established an early settlement nearby. About fifteen years later, Marlin

became positioned to gain rail service when the citizens of

Waco decided

that the easiest way to obtain a railroad was to build their own.

They proposed to "tap" the main line of the Houston & Texas Central (H&TC) Railway, which had

begun building north out of Houston toward the Red

River prior to the Civil War. The new railroad would be known as the Waco Tap, and it was

chartered by an act of the Texas Legislature on November 5, 1866. Marlin was

virtually assured of rail service; it was 21 miles southeast of Waco in the direction to reach

the H&TC, and its population was growing, reaching 500 in the 1870 Census.

The

Waco Tap had a charter but not much else, not even a corporation to own the

charter; that would come later. It also lacked an obvious

connecting point to the H&TC. During the War, the H&TC's end of track was at Millican, a tiny community between Navasota and

Bryan, well to the northwest of Houston...in

the direction of Waco. A straight line between Waco and Houston

would pass very close to Millican, Navasota and Bryan. The H&TC appeared to be

following the Brazos River toward Waco, remaining generally three to eight miles

northeast of the river. After the Civil War, the H&TC resumed construction with the same northwest

heading paralleling the Brazos, reaching Bryan (seven miles from the river) in

1867 and Hearne (five miles from the river) in

1868. Northwest of Hearne, the H&TC passed through Calvert (six miles from the

river and only 26 miles from Marlin) in 1869. Nine miles beyond Calvert, the H&TC heading turned away from

the Brazos, curving north-northeast. It continued on that heading another five miles

into the town of Bremond, newly founded by the railroad and named for its first

President, Paul Bremond. It was nine miles east of the river and sixteen

miles southeast of Marlin.

In Texas, the unsettled nature of the banking

system and financial markets during the post-War occupation by Federal troops

had motivated the Legislature to specify a procedure for organizing the Waco Tap

company, allowing two years in which to do so. The Waco Tap Railroad Co. was

formally established as the holder of the Waco Tap charter in November, 1868,

and it immediately began negotiating with the H&TC regarding the planned branch

to Waco. The railroads chose Bremond to be their connecting point; the H&TC had

already obtained a right-of-way there, but its tracks were still miles away. The

initial survey work for the Waco Tap began in December, 1868, and a year later, the

Houston Telegraph of December 16, 1869 quoted a

Waco Register

report that "Two miles of

the road are now graded. The junction, Bremond, has been laid off into lots, the

sale of which will commence soon." By the time the first scheduled

H&TC train rolled into Bremond in June, 1870, the railroads had agreed that

the H&TC would perform the construction work for the Waco Tap and would

acquire the line upon completion. In his classic reference book

A History of the

Texas Railroads (St. Clair Publishing, 1941), author S. G. Reed explains

that the H&TC...

"...secured an agreement to build a

branch from Bremond. The H. & T. C., however, did not intend to stop at Waco,

but to extend it through the Panhandle toward Colorado. So the name was changed

by the Legislature on August 6, 1870, to The Waco and Northwestern Railroad

Company."

|

H&TC's investors had been

looking at the prospect of building a lengthy branch line into the Texas

Panhandle with Colorado as the long term goal. Waco was an obvious target in

that direction, hence, it made sense to see what might be done under the

Waco Tap's charter. The terms of H&TC's charter prohibited it from

building branch lines until it had completed its main line to the Red

River (which would occur in late 1872), but that did not prevent the

H&TC from connecting to branch

lines built under other charters. Consistent with the idea behind the

Waco & Northwestern (W&NW), Colorado would soon become the foremost

target for Texas railroad expansion. Both the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe

Railway and the Fort Worth & Denver City Railway would be chartered in

1873, putting Colorado front and center as an explicit goal.

Left: Although the

first scheduled arrival of an H&TC train into Bremond reportedly took

place on June 15, 1870 to a welcoming crowd of a thousand people, this

news item from the Houston Telegraph

of Thursday, June 2, 1870, quotes the inaugural issue of the

Bremond Central Texan that

"preliminary opening day" at Bremond had taken place "Tuesday last",

which could either mean May 31 (two days earlier) or May 24 (Tuesday of

the prior week.) Various dignitaries of the H&TC were aboard the special

train. |

|

Left Top:

While the Houston Evening Telegraph

of June 2, 1870 reported grading north of Big Creek, within five miles

of Marlin...

Left Bottom:

...the Austin Daily State Journal

of June 14, 1870 quoted the Waco Register's

claim that "work" was "within seven miles of Marlin."

The difference may be attributable to the time lag in obtaining the

Waco Register report.

Right: Despite

H&TC taking over the construction effort, the work proceeded slowly. The grading between Bremond and Marlin took another

sixteen months. With the distribution

of ties along the grade also nearly finished, the roadbed was finally

ready for rails. (Austin Weekly

Democrat Statesman, October5, 1871)

Trains finally

operated into Marlin on February 24, 1872 and reached Waco on September

18, 1872. The W&NW was sold to H&TC five months later. Operations of the

Tap (which was still the favored nickname) through Marlin helped spur a

tripling of its population to 1,500 in the 1880 Census. |

|

As

explained by Reed, H&TC's track-laying for the W&NW did not stop at Waco; it

continued to Ross in

late 1872, ten miles farther northwest. There was nothing special about the tiny

community of Ross; it was simply in the right direction as H&TC wanted to

demonstrate its commitment to building to the Panhandle. The timing coincided with H&TC

completing construction into

Denison where it connected to a new bridge over the

Red River built

by the Missouri, Kansas & Texas (MK&T) Railroad coming south across Oklahoma.

Reaching the Red River fulfilled H&TC's charter requirement, freeing it to

build its own branch lines. It also attracted the attention of Charles Morgan,

owner of a major steamship line operating in the Gulf of Mexico. Morgan had

recognized the need to acquire railroads to move goods in and out of the major

ports servicing his steamship line. To this end, he organized Morgan's Louisiana

and Texas Railroad and Steamship Company and then bought the H&TC in early 1877,

naming his son-in-law, Charles Whitney, as President.

With Morgan and his

family now in control, the H&TC and its investors refocused on the northwest

extension. To build it, they elected to use a separate railroad for which a

charter was granted on May 30, 1879. It was called the Texas Central (TC)

Railway and was backed by many of the H&TC's existing investors. Charles Morgan's death at age 73 on May 8, 1878 put Charles Whitney

firmly in charge of both the H&TC and the TC, which commenced construction out

of Ross c.1879. The 55 miles from Bremond through Marlin to Ross remained under W&NW ownership

controlled by the H&TC.

In 1883, SP acquired all of the Morgan interests,

but

the H&TC was allowed to operate under its own name as a wholly-owned

subsidiary. The

Depression of 1882-1885 had already begun, and it hit railroads particularly hard.

The H&TC entered receivership in February, 1885 and SP lost control of it. In April,

1890, a financial reorganization resulted in the chartering of a new Houston &

Texas Central "Railroad" (not "Railway", as originally named.)

The W&NW had

been separated from the H&TC by the Bankruptcy Court and remained in

receivership, to be sold at auction. The new H&TC proceeded to buy the

Houston - Denison main line from the bondholders, and then SP

reacquired the new H&TC shortly thereafter.

The auction for the W&NW was held

December 28, 1892 on the steps of the McLennan County Courthouse in Waco. SP

lost the auction to Hetty Green, a wealthy Wall Street investor

represented by her son, Col. E. H. R. Green, but a lawsuit

was filed over the terms

of the sale pertaining to first mortgage bonds. A court set aside the results of the

auction, and after a lengthy court battle, a second auction was

held on September 3, 1895. This time, the auction was won by Wilbur F. Boyle, an agent

secretly acting on behalf of SP.

Extensive litigation followed. In a nutshell...

although the "new" H&TC owned the main line and rolling stock, the

remaining assets and obligations of the "old" H&TC and other Morgan

interests were still being unraveled to decide what could be liquidated

and paid to the bondholders. The

"old" H&TC's ownership of the W&NW created legal obligations regarding

first mortgage bonds (hence it had been separated so that the H&TC

reorganization could proceed.) Though Boyle had won the auction, he could not

complete the sale because the W&NW was still held in receivership while

the lawsuit against the "old" H&TC was litigated. The W&NW was being

operated in the interim under court supervision and was continuing to

make a profit. Should the profits be held for Boyle to receive, if and

when the sale was finally completed? Should they be paid to the W&NW's

bondholders? How much profit was there? It was a jobs program for

lawyers... The Federal District Court in Galveston handled the case and

assigned a Special Master to sort out the details and

issue reports to the Court. Naturally, every report from the Special

Master resulted in motions to the judge by one side or the other

disputing various details. Finally, after appellate rulings from the

Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans, the case wound down.

Right: The

Galveston Tribune of July 7,

1898 reported the end of the W&NW receivership. Six days earlier, Boyle

had been able to convey the W&NW property title to SP's new H&TC

subsidiary. Although Alfred Abeel is noted in the article as the Special Master, he

was actually the court-appointed Receiver for the W&NW. The Special Master

was Col. William L. Prather, who resigned his position with the Court on

February 19, 1900 (the remainder of the lawsuit was still

going on!) as he became President of the University of Texas, an

institution he had served for many years on the Board of Regents. He is

the namesake of

Prather Hall on the Austin campus. |

|

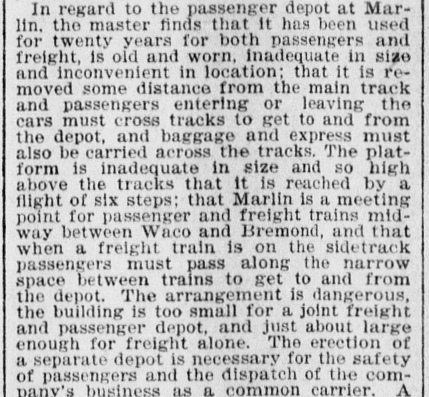

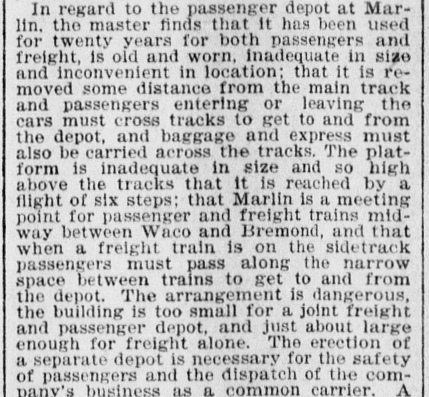

While Alfred Abeel had been running the W&NW as

the court-appointed Receiver, the railroad had performed well. Abeel had to get Court permission for capital expenditures, but since the

railroad was making a profit, such approval was typically forthcoming. By 1896,

Abeel knew he needed new depots in Waco and Marlin.

|

Left and Above:

Galveston Daily News, April 18,

1896 |

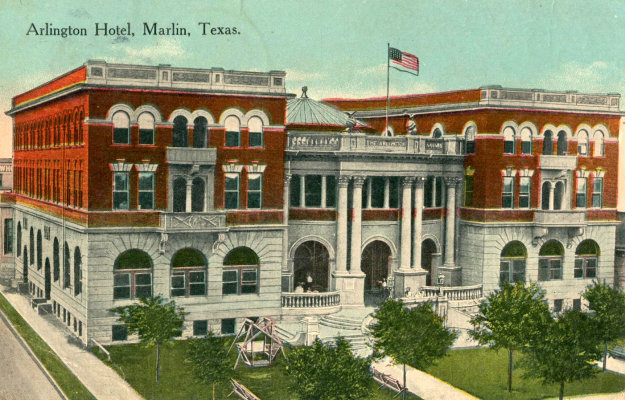

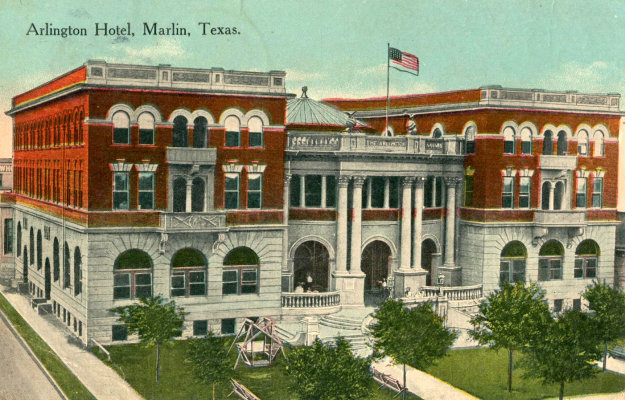

In 1892, the City of Marlin accidentally discovered hot mineral water

when it drilled an artesian well for municipal use. Soon, the "healing benefits" of

Marlin's mineral waters were being marketed to the general public, many of

whom arrived by train on the W&NW. The first bath house was completed in 1895

and the Arlington Hotel was built that same year as an elaborate facility for

visitors who came to enjoy spa treatments. Additional hotels were built,

and a substantial industry

developed in Marlin around bath houses and spa facilities catering to

travelers who came to "take

the waters." Four major league baseball teams held spring training in Marlin

in various years (c.1904-1918), always staying at the

Arlington Hotel. The spa industry continued through the 1930s and then

began to fade away.

Left:

It seems likely that the growing influx of spa visitors to Marlin

arriving on the W&NW motivated Abeel to request approval of a new passenger depot. The judge

assigned it to Special Master Prather who issued a favorable report on

the idea. Abeel's request also included building a new freight depot at

Waco. [Note that "UP" in the headline does not refer to Union Pacific!

It is simply that from the perspective of headline writers in the

Galveston press, almost everything happening in Texas was "up", as in

"up north".] |

Below: The mineral waters industry in

Marlin was no "mom and pop" operation. (University of North Texas collection,

Portal to Texas History)

As the mineral waters fed Marlin's economic growth in the late 1890s,

the town

became targeted for additional rail service. The International & Great Northern

(I&GN) Railroad, one of the largest in Texas, had begun to contemplate a new

rail line to connect Fort Worth and Waco with

Houston and Galveston, with the

route passing through Marlin. The I&GN

was controlled by the family of rail baron Jay Gould who had died in December,

1892. His rail empire had passed to his sons George and Edwin. Edwin ran the St. Louis Southwestern ("Cotton Belt") while George ran the

I&GN and the Texas & Pacific, plus additional railroads outside of Texas

(notably, the Missouri Pacific, which had been evicted from Texas when its lease

of the MK&T was broken by the Texas Supreme Court in 1891.) Because

Fort Worth had become a major rail gateway to the north and west, the belief was

that a faster, more direct route from Fort Worth to Houston and the Port of

Galveston would pay dividends for the I&GN.

Like

many other rail executives, George Gould elected to charter a separate railroad, the

Calvert, Waco and Brazos Valley (CW&BV), to handle the construction of the

new line, ostensibly from

Valley Junction (near Hearne) to

Waco and Fort Worth.

At Fort Worth, the I&GN would connect with several railroads; it had no existing operations there,

but the Texas & Pacific led by Gould had a major presence. Although Valley

Junction was on the I&GN main line between Longview and Laredo, neither of those

endpoints was in the direction of Houston, hence there was no practical benefit

to Valley Junction being the southern terminus of the new line. The charter was

revised on May 6, 1900 to make Bryan the southern terminus, but there was no

I&GN connection there at all. From Bryan, a trackage rights agreement with the

H&TC would be needed to reach Houston, and there was no assurance that a deal

could be made (no doubt H&TC was very

unhappy with I&GN's plan to serve many of the same towns along the Brazos.) The charter was revised again in December,

1900 to move the south endpoint to Spring, just north of Houston on

another I&GN main line that ran to Palestine. It was feasible to build

to Spring, and the line from Spring into Houston connected with the Galveston,

Houston & Henderson (GH&H) of which I&GN was half-owner. I&GN

possessed an independent and unlimited right to use the GH&H tracks to reach Galveston.

|

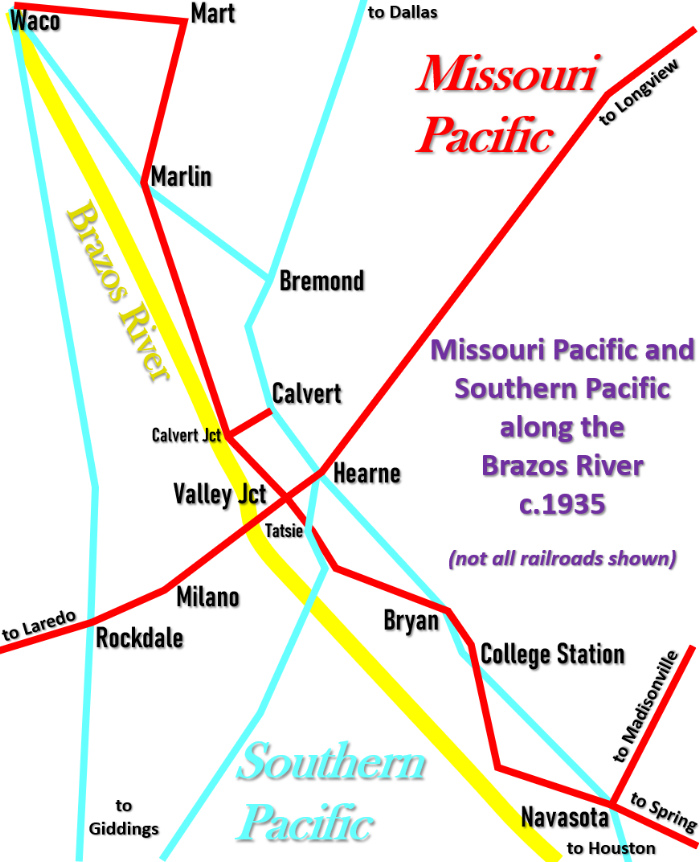

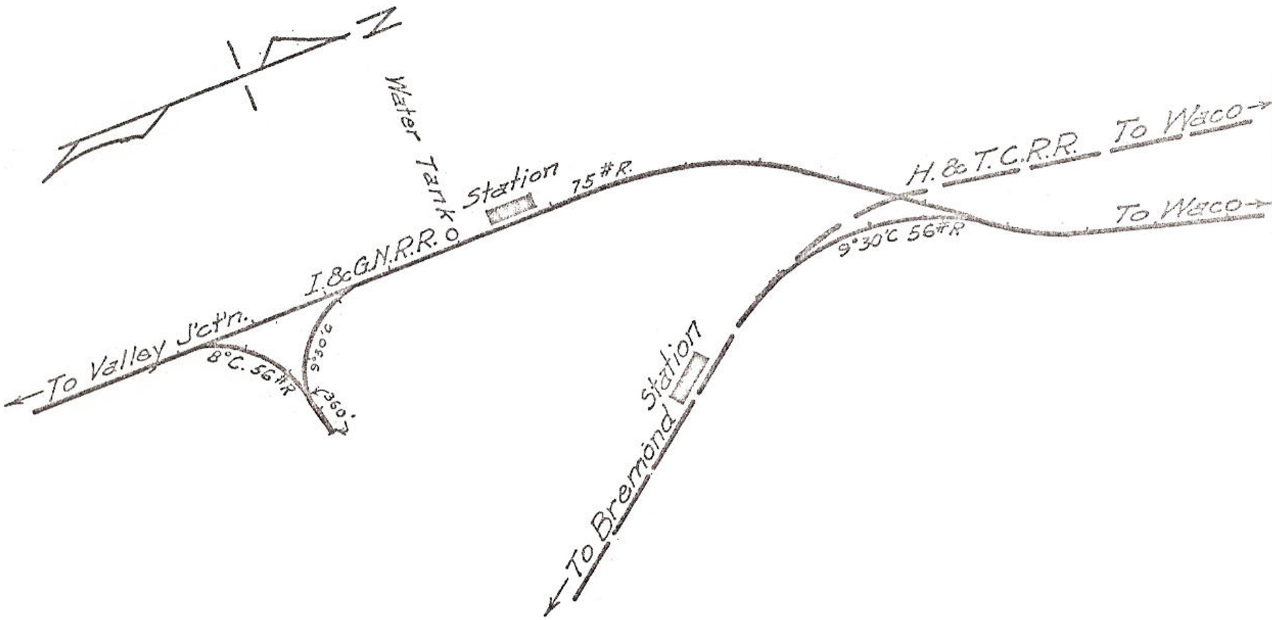

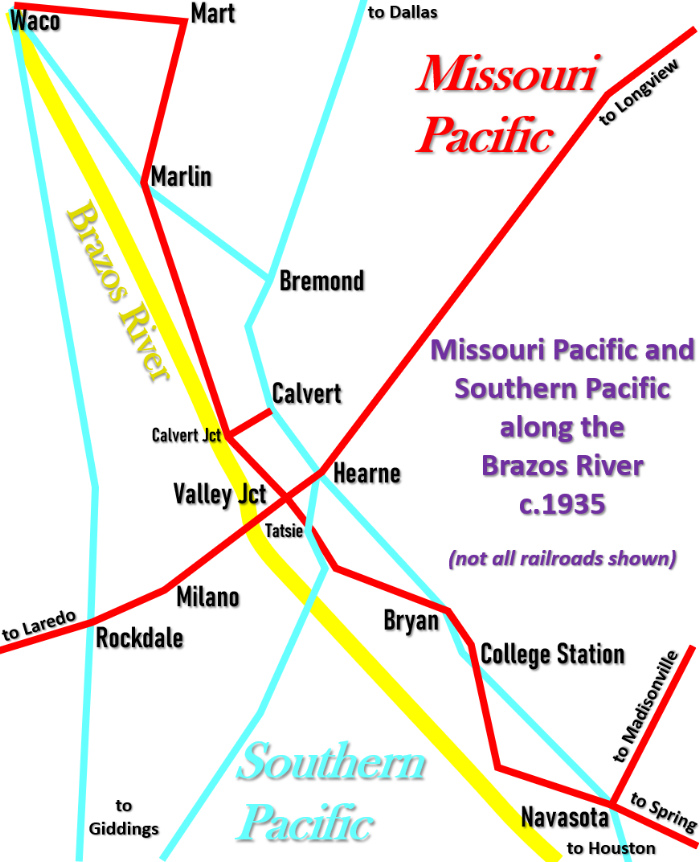

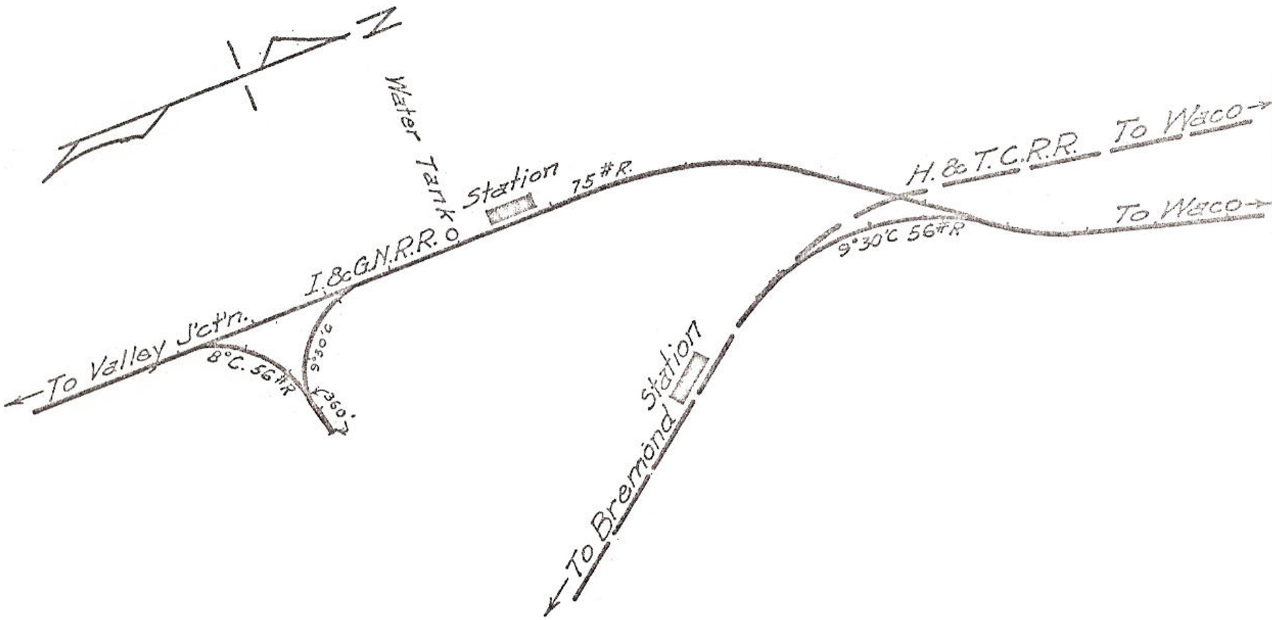

Left:

area map showing SP and MP rail lines along the Brazos River between Waco and

Navasota -- other railroads not shown

From Waco, the new

I&GN tracks would parallel the Brazos River much of the way south,

passing through Marlin, Valley Junction, Bryan, College Station and

Navasota. Except for Valley Junction, all of these towns were already

served by the H&TC, and Valley Junction was only four miles from the

major H&TC yard at Hearne. (Note that SP's line from Giddings through

Tatsie to Hearne shown on the map was built later, c.1914.) The two railroads' proximity created serious conflict

between them, and there was litigation associated with

crossings and rights-of-way.

The entire line between Spring and Fort

Worth was built in disjointed pieces by multiple I&GN crews. New

construction reported annually to the Railroad Commission of Texas (RCT)

reflects the nature of the effort.

1900: Calvert to Valley Junction, 14.3 miles

(CW&BV)

1901: Valley Junction to Bryan, 22.75 miles (CW&BV)

1901: Calvert Junction to Marlin, 28.65 miles

(CW&BV)

1902: Bryan to Spring, 78.22 miles (I&GN)

1902: Marlin to Waco, 41 miles

(I&GN)

1903: Waco to Fort Worth, 94.55 miles (I&GN)

In February,

1901, an act of the Texas Legislature allowed the I&GN to acquire and

merge the CW&BV, hence all post-1901 mileage is attributed to the I&GN.

In addition to Tower 191 at Marlin, the locations on this map that

were interlocked are Waco (Towers 59, 21,

8 and

144), Valley Junction

(Tower 194), Hearne (Tower 15), Tatsie (Tower 140), Bryan (Tower 36),

College Station (Tower 7), Navasota (Towers

9 and 41), Milano (Tower 23)

and Rockdale (Tower 54).

The overall

design of the I&GN line between Spring and Fort Worth sacrificed grade

quality for construction speed, and opted for circuitous routes in

places to mitigate direct competition with the H&TC. This did not bode

well for the long term since

the I&GN's objective was a faster

route to Houston. Its Fort Worth Division became notorious for wrecks,

derailments and slow orders due to bad roadbed, poor signaling and

numerous curves. The Brazos River and its

tributary creeks flooded periodically creating more problems.

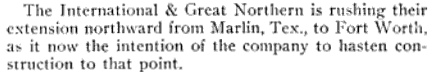

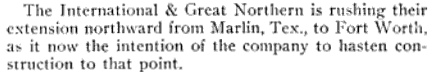

Above:

Railway Journal, April, 1901 |

Wayne Cline described the I&GN construction in his book

The

Texas Railroad ((c) Wayne Cline, 2015)...

...the Fort Worth Division was built

with "rapid-fire" techniques, which were not noted for producing safe and

durable results. By 1902 short trains were rocking slowly along the wavy tracks

of the new Fort Worth Division, and the following year found them creeping over

a new 45-mile branch between Navasota and Madisonville."

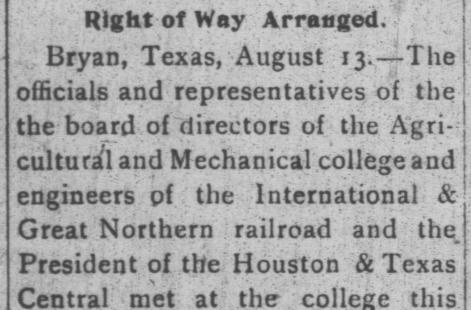

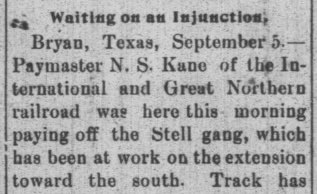

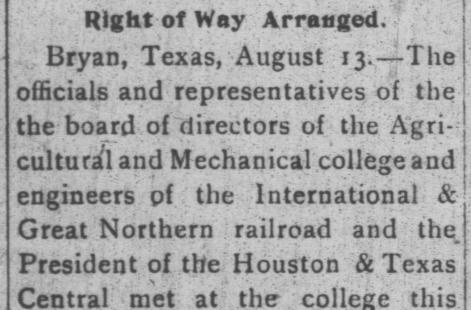

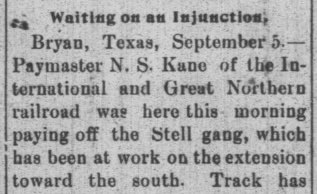

Above Left: The

Navasota

Daily Examiner

of August 14, 1901 reported on a meeting between the two

railroads at College Station regarding the I&GN's "right of way ... through the

college grounds." Above Right:

Three weeks later, the September 6 issue of the newspaper reported that track work had been suspended

within a half-mile of College Station due to an injunction obtained by the H&TC

to temporarily prevent the I&GN from crossing the H&TC's tracks. The I&GN eventually won the case and was allowed to

proceed across the H&TC at College Station. This became one of the earliest

crossings to be interlocked, commissioned by RCT on February 21, 1903 as

Tower 7.

H&TC instituted a couple of legal roadblocks to try to

deter the I&GN's construction, or at least steer it away from putting its grade

directly beside the H&TC tracks. They lost in court, but they may ultimately

have influenced I&GN's route. Despite grade crossings of the two railroads at

Navasota, College Station, Bryan and Marlin, the tracks never ran side-by-side

for any significant length until the crossing at Tatsie was built by SP in 1914

as part of the "Dalsa Cutoff" between Giddings and Hearne.

That

the Fort Worth Division's construction had begun at Calvert (a town on the H&TC

between Bremond and Hearne) is perhaps indicative of the chaotic nature of I&GN's planning. S.

G. Reed wrote that the original concept was to build from

"...Valley Junction on the Longview-San Antonio Line through Calvert to Fort

Worth...", but despite Calvert being prominent in the CW&BV

name, it wasn't even on the main line when the project was

finished. The initial construction by the CW&BV began at Calvert and went west far enough (five miles) to cross the Little

Brazos River. Safely ensconced a quarter mile west of the Little Brazos and a

mile east of the "big" Brazos, the tracks made a 90-degree turn to the

south to reach Valley Junction. The turn became known as Calvert Junction when

it was subsequently used as the starting point from which to build north to

Marlin. Thus, the actual main line ran between Valley Junction and Marlin, with

Calvert merely the endpoint of a five-mile spur.

Sanborn Fire Insurance maps of Calvert show that the I&GN and H&TC served the

same cotton processing facility but otherwise did not connect at Calvert.

Because of population growth

in Marlin, the I&GN had difficulty obtaining a right-of-way through town,

and ultimately, the only choice was to run its tracks through the heart

of Marlin on Falls St. and Ward St. This made operations in town very slow and

somewhat dangerous due to wagon and pedestrian traffic. The

Jefferson Jimplecute of February 2,

1907 (in what can only be characterized as random filler from

a town 180 miles away) reported that while "improving its track",

the I&GN "...is making needed improvements to portions of Ward and

Falls streets." Perhaps Jefferson residents liked to go to Marlin

to take the waters?

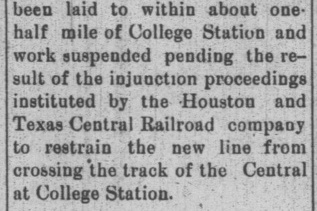

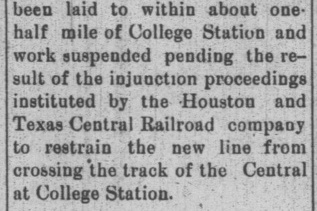

Right:

This snippet from the 1903 Sanborn Fire Insurance Co. map of Marlin

highlights the I&GN track running through Marlin's Public Square, where

Falls St. becomes Ward St. along the east side of the Falls County

Courthouse. A county courthouse located this close to a railroad main

line must have been rare in Texas, even in 1901. It was obviously a busy

area filled with people and commerce. Delays were mitigated somewhat by

the I&GN passenger depot being located one block south of the square; trains would have been moving slowly

anyway arriving or departing the depot.

To the north, the H&TC

(W&NW) already occupied the optimum route between Marlin and Waco, so the I&GN chose to take a circuitous path from Marlin north to

the community of Mart and then west to Waco. While this was an economic boon for

Mart -- its population grew from 300 to 3,000 over the next decade -- it made the I&GN's route slower and more expensive to operate.

Eventually, Mart became the I&GN division point and a yard was built

there. Operations to the south were in the Mart District and operations

to the north were in the Fort Worth District. |

|

The I&GN went into receivership in 1908. This was

partly from economic conditions and partly from financial miscalculations by George Gould

pertaining to railroad investments elsewhere in the U.S. Gould issued a

statement blaming it on orders issued by RCT that would require large expenditures to improve the I&GN's infrastructure.

RCT stuck to its order, though it was roundly criticized throughout the railroad

industry. While other railroads were ordered to make similar improvements, RCT

rightfully had very serious concerns about the I&GN. The new Fort Worth Division

was the culprit, though it comprised just 25% of the I&GN's track

mileage. Wayne Cline explains that after Gould had taken control in the wake of

his father's death in late 1892...

"...the International and Great

Northern had compiled a reasonably acceptable safety record, but it went rapidly

downhill shortly after the Fort Worth Division was constructed. In 1904,

casualties suddenly soared when 139 workers and passengers were injured --

almost twice the average for the previous ten years. ...[in 1908] Commission records

showed that 99 wrecks had occurred on the I&GN since the summer of 1907, and 41

of them occurred on the newly laid track of the Fort Worth Division."

In 1911, a new I&GN company was organized to take over the assets and operations of the old

company, with the Gould family still in charge. In early 1914, the I&GN again

returned to receivership, this time for several years which included the period under the U. S.

Railroad Administration during the World War. Another new company, the International -

Great Northern (I-GN) was formed in 1922 to acquire the I&GN out of

foreclosure, at which point the Gould family was no longer involved.

The I-GN's financial

reorganization coupled with its service to many of the major cities in Texas and

its thousand miles of track made it an attractive

target for acquisition. MP had gained independence from the Gould family in 1917

and wanted to buy the I-GN to reenter the Texas market, but the sale was nixed by the Interstate

Commerce Commission (ICC). Going to Plan B, MP

helped the New Orleans, Texas & Mexico (NOT&M) Railway buy the I-GN.

The NOT&M had become the corporate entity for a collection of railroads that

operated between New Orleans and Brownsville using the moniker Gulf Coast

Lines (GCL) under executive control of the St. Louis - San Francisco

("Frisco") Railway. The GCL had gained independence during the Frisco's

receivership in 1914 and it was also a candidate to be acquired by a larger

railroad. The

ICC approved NOT&M's purchase of the I-GN in 1924, and then allowed MP to buy the NOT&M on

January 1, 1925. This gave MP the I-GN plus all of the NOT&M railroads -- a

sudden and massive presence for MP in Texas. In 1933, MP went into a lengthy

receivership which likewise compelled a receivership for the I-GN.

Operating for more than two decades under court supervision, MP finally emerged from bankruptcy in 1956. MP dissolved the I-GN

at that time and integrated

its operations under the MP name.

In 1927, SP chose one of its Texas

subsidiaries, the Texas & New Orleans (T&NO) Railroad, to become its primary

operating entity for Texas and Louisiana. SP began leasing its various Texas and

Louisiana properties to the T&NO and in 1934, merged them into the T&NO

corporation. Although this did not include the Cotton Belt, of which SP had

gained control in 1933, it did include the

H&TC and W&NW. All subsequent SP operations through Marlin were under the T&NO name.

|

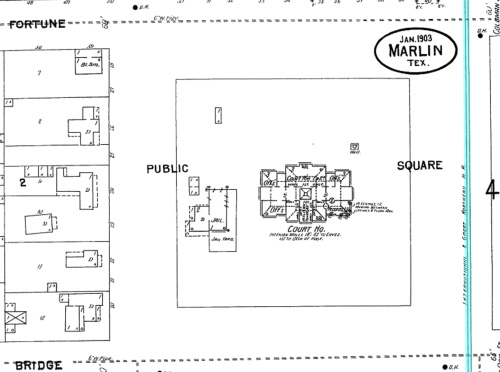

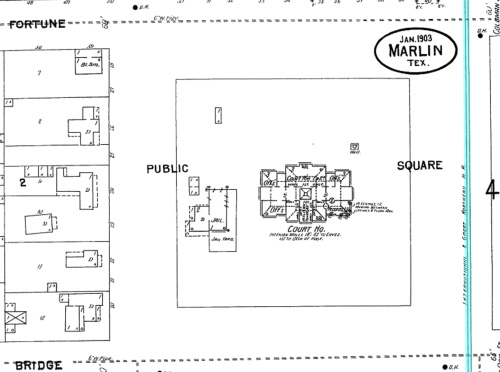

Left:

1915 track chart of Marlin from the MK&T railroad's Office of the Chief Engineer

(courtesy Ed Chambers) Below:

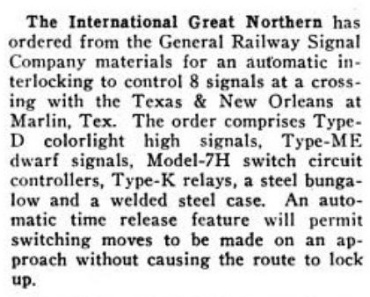

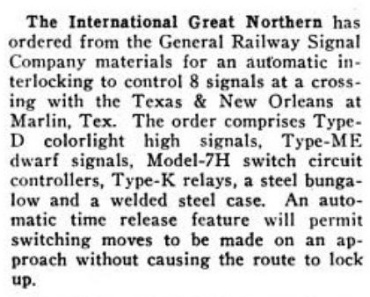

An automatic interlocker for Marlin was ordered in 1945 by the I-GN. It was

commissioned as Tower 191 by RCT on January 18, 1946.

Above:

Railway Signaling, June, 1945 |

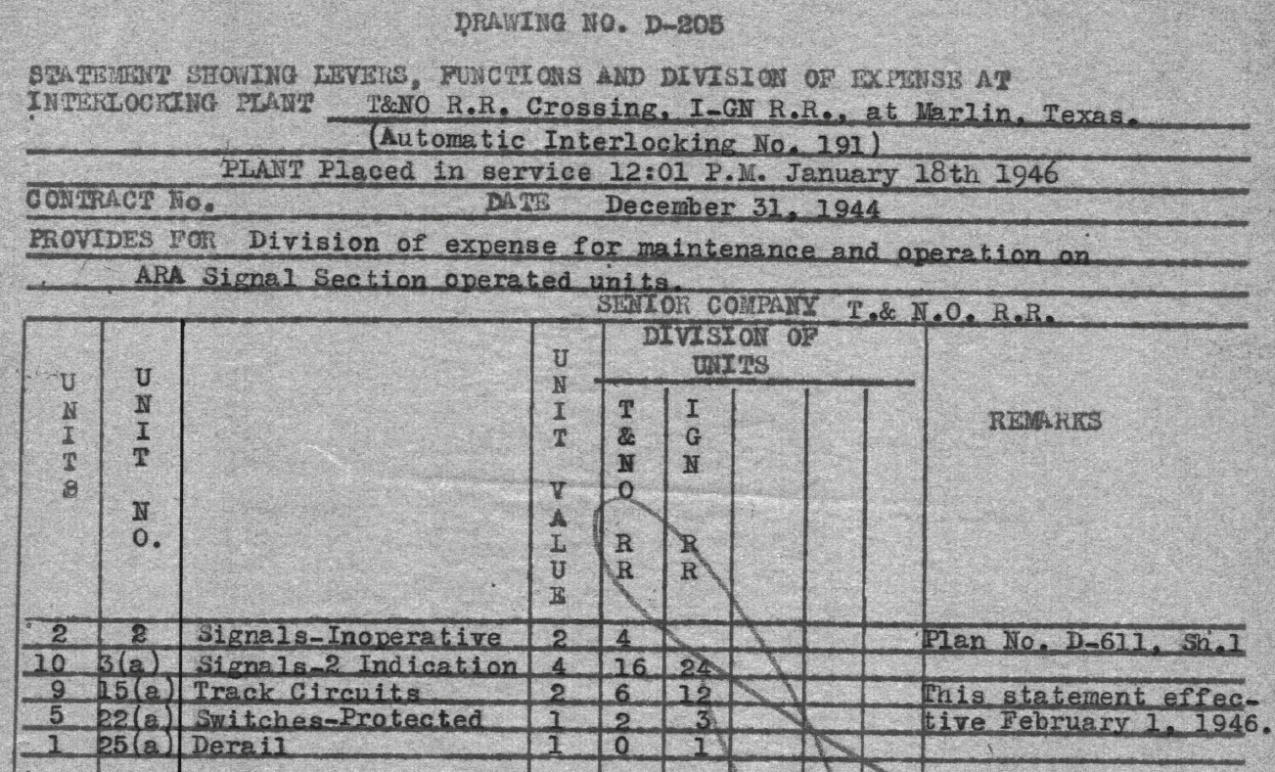

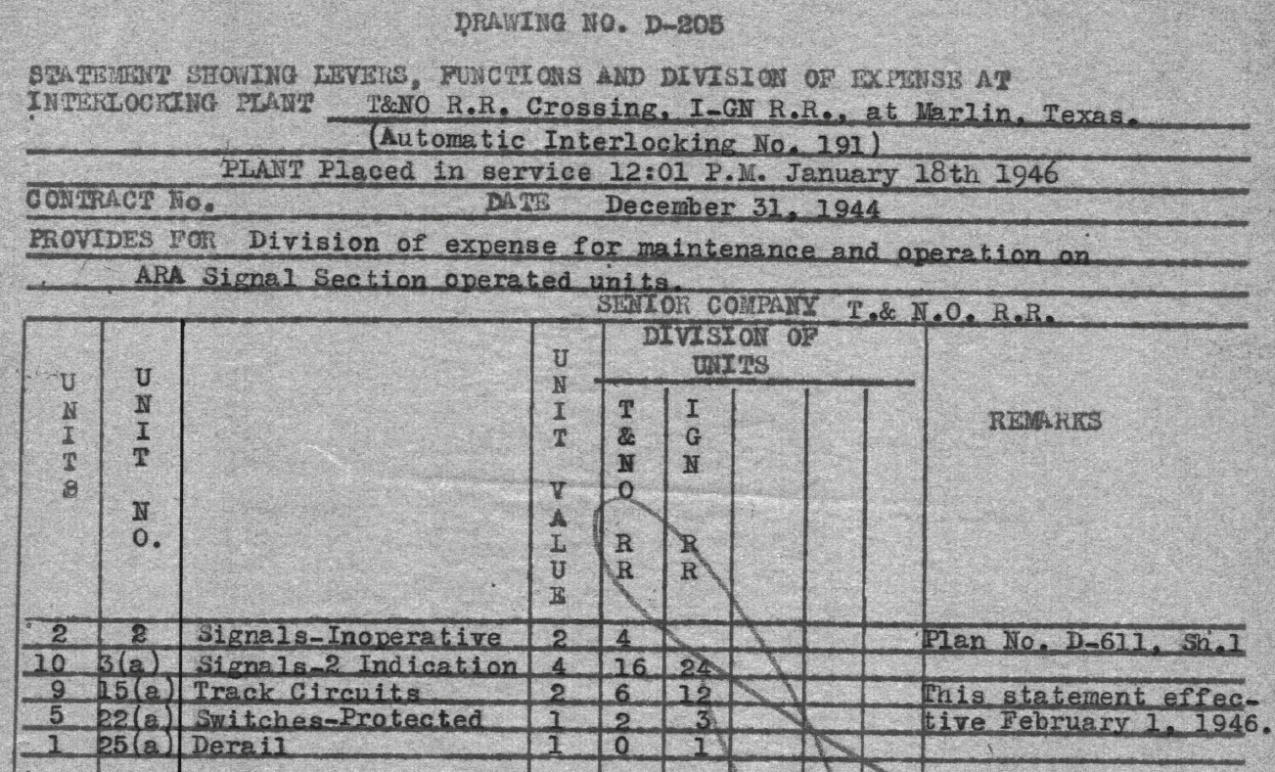

Right:

SP used an internal drawing known as a D-205 to provide summary

documentation for the interlockers in which it had a financial interest.

The upper portion of the original D-205 for Tower 191 shows that the

contract between the two railroads dated to the last day of 1944. Just

over a year later, the interlocker was commissioned for operation. Since

the T&NO was the "Senior Company", the I-GN had responsibility for the

capital expense for the interlocking plant and associated signals. The

bottom of the document (not shown) indicates that the recurring expenses

were shared in the ratio of 41.18% for the T&NO and 58.82% for the I-GN.

(Carl Codney collection)

The specific impetus to interlock the Marlin crossing in 1945 rather than years earlier is

undetermined. Presumably the crossing was gated, most likely against the T&NO.

The Waco branch had never been a main line for SP, and a 1941 T&NO timetable

shows only one mixed train daily each way through Marlin. Despite all of the

infrastructure problems during the Gould era, MP made substantially greater use

of its Fort Worth Division. Assuming the crossing was gated against the T&NO and

that MP trains were operating at restricted speed near the depot anyway, MP might

have had little incentive to pay the capital expense for an automatic interlocker.

Thus, the decision to interlock the Marlin crossing might have resulted

from an order by RCT. In October, 1959, the D-205 was revised because a T&NO

siding or spur track was removed. This reduced T&NO's recurring expense

share to 36.51%. |

|

|

The precise date the Marlin interlocker was commissioned

for operation is undetermined, but it is listed as an automatic interlocker in a

T&NO Employee Timetable (ETT) dated May 19, 1946. With a June, 1945

ordering date, it was probably installed in early 1946.

For

whatever period of time the I&GN tracks from Valley Junction ended at

Marlin in 1901, there would have been no reason to extend them past the

depot to the point where they crossed the H&TC farther north. Thus,

installation of the crossing diamond most likely occurred when the I&GN

proceeded with construction from Marlin to Waco in 1902. On that basis,

I-GN would have taken the lead in ordering the interlocker because it

would have been paying all of the capital expenses. For crossings that existed as of 1901, RCT required

the railroads to share interlocker capital expenses equally, but the

Marlin crossing most likely dated from 1902.

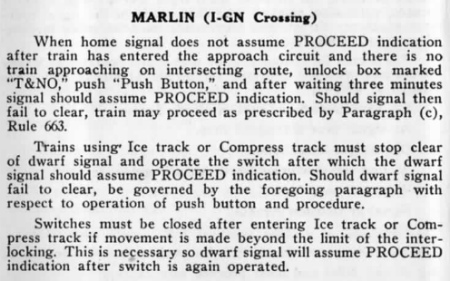

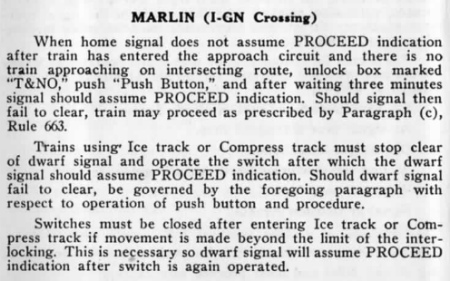

Left: These special instructions from the 1946

ETT indicate that there was a control box mounted at the crossing to be

used for overriding the signals when necessary. This is common for

automatic interlockers, e.g. Tower 70, Tower 103,

Tower 127. The "Compress track" refers to a

cotton processing facility identified on Sanborn Fire Insurance maps as "Exporters and Traders Compress and Ware

Ho." southwest of the diamond. It was served by both railroads. |

Over many years, SP's track and infrastructure

development in Texas had rendered the route through Marlin unnecessary. The mixed train

daily on T&NO's schedule in 1941 remained the only regular operations on the

line. A 1962 timetable lists only a single daily freight in each direction;

passenger service had apparently been dropped. With little commerce on the line,

the T&NO

proceeded to abandon its Waco Branch through Marlin in 1965. MP took this opportunity to eliminate the lengthy segment from Marlin to Waco

via Mart by purchasing T&NO's more direct route.

Rather than connecting to the T&NO tracks at the Tower 191 crossing, MP chose to eliminate

the tracks on Ward St. and Falls St. by using T&NO's entire route

through town. Tower 191 no longer served a crossing so it was decommissioned, but

the plan necessitated construction of a short connecting track in south

Marlin. Today, this route remains a UP main line.

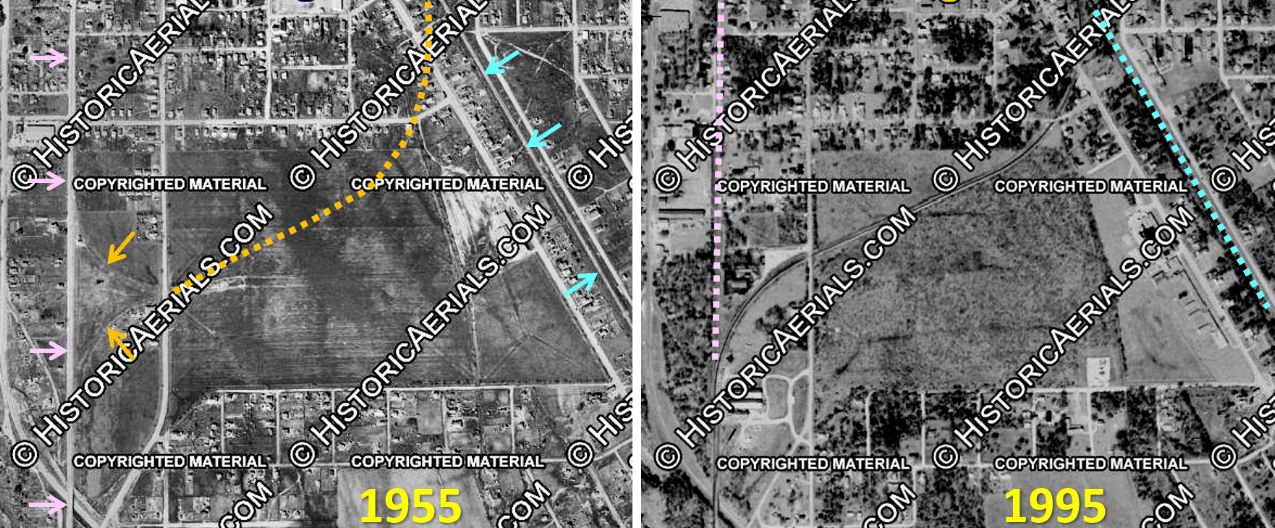

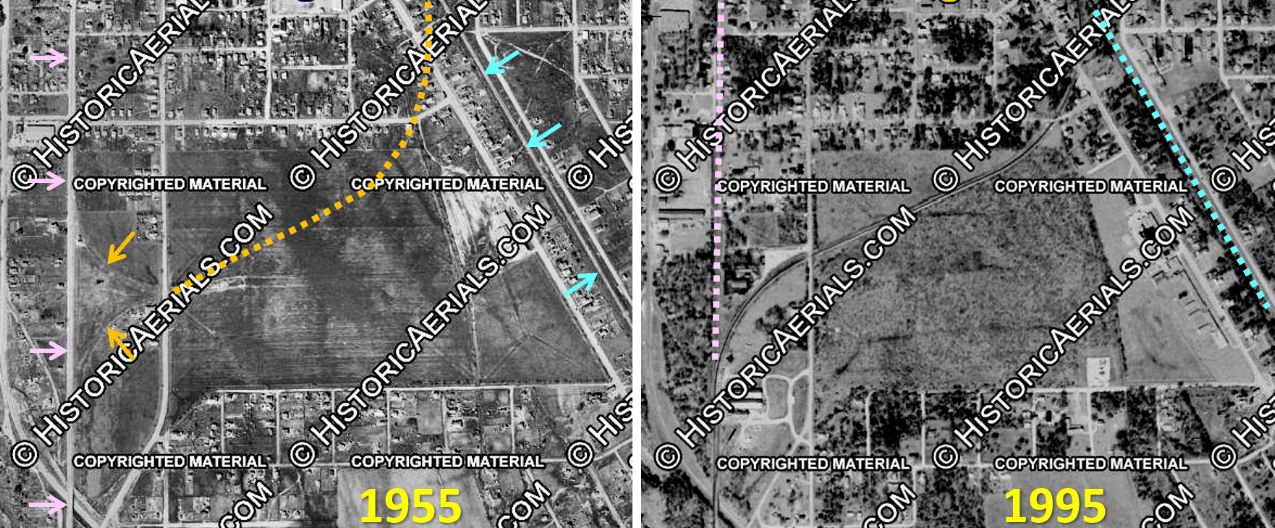

Above: These two aerial images ((c)historicaerials.com)

captured forty years apart show the revisions to the tracks on the south side of

Marlin that resulted from MP buying SP's route to Waco in 1965. Prior to the sale, the

MP tracks (pink arrows) ran north/south along the west side of Marlin while the

SP tracks (blue arrows) ran northwest/southeast on the east side of Marlin. The 1955

imagery shows that MP had a wye (orange arrows) going east off the main line;

the wye also appears on the 1915 track chart. MP used the south leg of the wye as the starting point for the new connector

(orange dashes) that ran northeast and curved onto SP's tracks. The connector is visible in the

1995 image. The end result was that the MP tracks north of the connector (pink

dashes) and the SP tracks south of the connector (blue dashes) were abandoned.

Below Left:

Looking west, the north and south legs of MP's wye merged at the Bennett St.

grade crossing. The south leg was used as the lead for the connecting track to

carry MP trains to SP's tracks and is now part of UP's main line. The north leg

was abandoned, but its path ran northwest past the utility pole at right of

center where a vague right-of-way is visible extending into the distance.

Below Right: Looking north-northwest from

the former Tiller St. grade crossing, SP's right-of-way from Bremond shows a slightly

elevated grade paralleling Kennedy St.

About 0.6 miles distant, the grade becomes occupied by UP's tracks where MP's

connecting track merged into SP's line to Waco. The connecting point was

formerly the Conoly St. grade crossing, but barriers were erected to block the crossing and little remains of Conoly St. today.

(Google Street View images)

In 1982, UP acquired MP but continued to operate it as

a wholly-owned subsidiary. In 1996, UP acquired SP and shortly thereafter, SP

and MP were integrated into UP's operations and they ceased to exist as separate

railroads.

Last Revised: 9/13/2024 JGK - Contact the

Texas

Interlocking Towers Website.