(All John W. Barriger III photos on this webpage are provided courtesy of the John W. Barriger III National Railroad Library.)

|

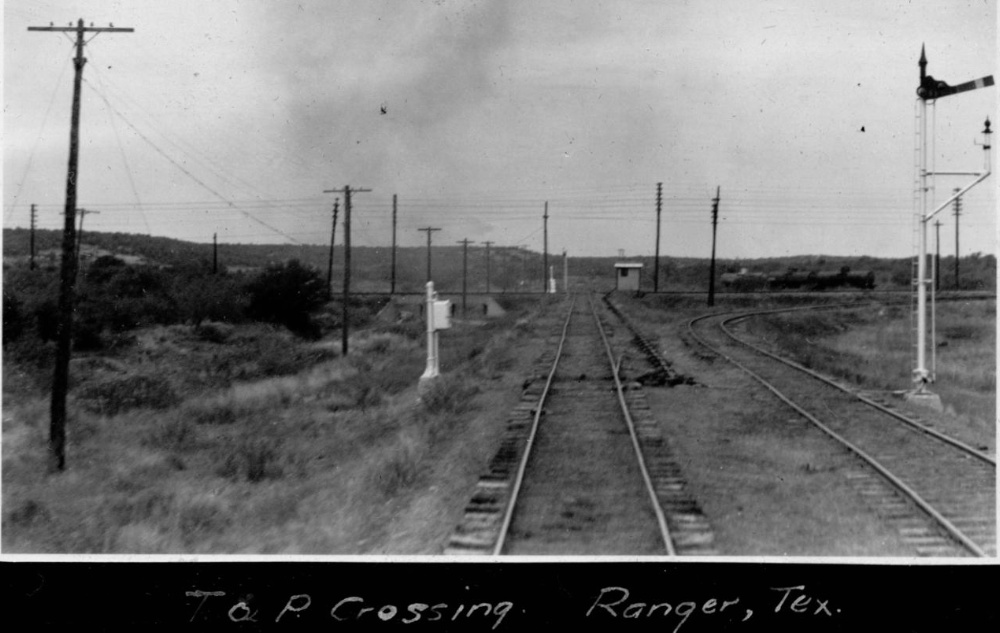

Left:

On October 1, 1940, John W. Barriger III took this photo of the Tower 122

crossing from the rear platform of his business car while traveling south toward

Dublin. The view is west-northwest along the former Wichita Falls, Ranger & Fort

Worth which had been acquired by the Wichita Falls & Southern in 1926. Although

the Texas & Pacific (T&P) line ran generally west out of Fort Worth toward

El Paso, it came through Ranger on a south-southwest heading. The

T&P tracks are visible just in front of the white hut at the X-pattern crossing. The

connecting track in the north quadrant of the crossing is occupied by three tank

cars. The east quadrant connector is vacant and there were no connectors west or

south of the diamond. Barriger was traveling on an inspection trip for the

Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), for which he was the head of the

railroad division. Barriger would leave RFC in 1941 and move to the Office of

Defense Transportation during World War 2. (All John W. Barriger III photos on this webpage are provided courtesy of the John W. Barriger III National Railroad Library.) |

| Right: Bruce Blaylock provides this photo by Bob Richardson taken on July 15, 1946. It shows Missouri - Kansas - Texas train #35 approaching the Tower 160 interlocking at the Texas & Pacific crossing at Cisco. By this date, the interlocking was automatic; the post in the foreground hosts two boxes housing manual override controls for use by train crews should the interlocker fail to present the proper signals. Bruce describes the locomotive... "MKT 315 is an American type locomotive built by Baldwin in 1892 as MK&T 284 and extensively rebuilt by the Katy in 1924 with a new boiler. ...It was scrapped in 1949..." The train is returning to Waco from its round trip to Stamford, scheduled to arrive at 10:10 pm. |

|

Chartered by Congress in 1871 with

instructions to build a transcontinental railroad from Marshall, Texas to San

Diego, California, the Texas & Pacific (T&P) Railway had only reached

Fort Worth by 1876.

Progress toward El Paso was further delayed, but the T&P finally resumed construction westward

in 1880. Fifty miles later, the Brazos River was bridged in July, and the T&P

used the remaining months that year

to complete the tracks into the new town of Baird. Named for a T&P survey

chief, Baird was reached in December, 1880, 140 rail-miles west of Fort Worth. It

would become an important operations center for the T&P.

Midway between the Brazos River and Baird

lay Eastland County. Like most of the land this far west of Ft. Worth, the

county barely had any population at all, largely due to the lingering effect of

conflicts with Comanche tribes into the early 1870s. A state law passed in 1874

started the process of formally organizing Eastland County; it had previously been "attached" to Palo Pinto

County, the county to the northeast through which the Brazos River

flowed. The first District Court meeting in Eastland County was held at

Flanagan's Ranch on June 1, 1874 at which time the name Merriman was chosen for

that location, the temporary county seat pending an election. To capitalize

on the election for a permanent county seat, two real estate developers

purchased land about ten miles west of Merriman and platted a townsite,

convinced that a location closer to the geographic center of the county would be

preferred by voters. When the election was held in August, 1875, the voters agreed,

even though the winning site was apparently referenced only as "the C. S.

Betts survey". Thus, the new town of Eastland, named for the county, was

established on the C. S. Betts survey. By the end of September, 1875, the town had a county

courthouse and a growing population.

Galveston Daily News, April 25, 1874 |

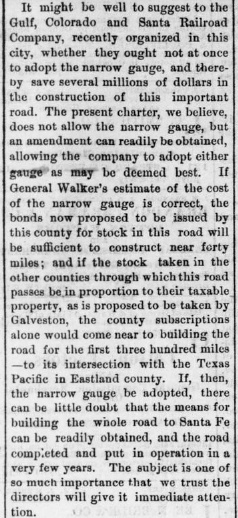

Left: Even before it was organized, Eastland

County was viewed as a future rail route from the south into the Texas Panhandle. Less

than a year after the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe Railway was

chartered by Galveston interests to build a new rail line off the island

toward Colorado, editorials in the

Galveston Daily News were demanding Santa Fe adopt a narrow gauge design

and proceed directly to an "intersection with the Texas & Pacific in

Eastland county". Never mind that Santa Fe track construction had yet to commence,

and ignore the fact that the tracks of the T&P had yet to reach Fort Worth let alone proceed

into west Texas. The Eastland county rail crossing was simply inevitable. Ultimately, there would be three

rail crossings of the T&P in Eastland County, but none of them involved

Santa Fe. Right Top: announcement of the first District Court meeting in Eastland County -- the name chosen for the county seat was Merriman Right Bottom: Security, land prices, elections, lack of rainfall -- the news wasn't much different in farm and ranch country 150 years ago. Below: election results reported by the Galveston Daily News, August 21, 1875  |

Galveston Daily News, April 3, 1874  Galveston Daily News, September 18, 1874 |

As T&P's construction crossed the Brazos and proceeded

southwest through the southern part of Palo Pinto County, Eastland offered free

right-of-way (ROW) through the town, land for a depot, and a supply of town lots for

the T&P to sell or use. While such inducement might seem superfluous since the

county seat would be an obvious route choice, railroads were not above founding

their own towns -- where they would own all of

the town lots -- to compete with existing towns (as the citizens of

Kingston discovered.) T&P accepted the offer and

built through Eastland in the summer of 1880. Beyond Eastland, the T&P ROW

followed the drainage of the North Fork of the Leon River west-northwest for

about three miles. It then curved slightly southwest for several miles before

briefly rejoining the same river drainage eight miles west of Eastland. From

there, hills and creeks caused the route to meander somewhat although it was on

a generally due west heading toward the chosen site of Baird, 25 miles distant. Back to the

east, prior to

reaching Eastland, T&P's tracks passed within two miles

of Ranger Camp Valley, an area named for an outpost used by the Texas Rangers

that was about ten miles northeast of Eastland. A

tent city had developed around the camp and continued to prosper even after the

Rangers' presence diminished in the latter 1870s. With the railroad nearby, the

tent city relocated to be trackside and morphed into a legitimate

town. A Post Office was granted to this new town, Ranger, in December, 1880.

The idea that Eastland County would one day host a

major rail junction was common thinking in the 1870s. It was an area of

relatively flat land west of the river breaks of the Brazos, but it remained far

enough east to have better water sources and fewer hills and ridges than

Callahan County to the west. The T&P was committed to building across Texas from Marshall to El Paso

and its route was almost guaranteed to pass through Eastland County. For a north / south

crossing of the T&P, other railroads, particularly the Gulf,

Colorado & Santa Fe (GC&SF) and the Houston & Texas Central (H&TC), were

proclaiming their intentions to build toward the Texas Panhandle and into

Colorado to gain new sources of commerce for Houston and Galveston. And although

it would not pass through Eastland County, the Fort Worth & Denver City (FW&DC)

expressed by its name its intentions to be part of a line planned from Denver to Ft. Worth, where

connections to Houston and Galveston were already assured. As noted above,

an editorial in the Galveston Daily News of

April 25, 1874 strongly encouraged the GC&SF to build a narrow gauge line

directly to Eastland County as quickly as possible. It was, however, the Texas Central (TC) Railway, an

offshoot of the H&TC, that was the

first to cross the T&P west of the Brazos.

The tiny

community of Ross, a few miles north of Waco, was where the Waco & Northwestern

branch of the H&TC had terminated in 1872. After a delay of several years

during which the H&TC was acquired by steamship magnate Charles Morgan, H&TC's investors

were ready to continue building out of Ross toward the Texas

Panhandle. They elected to do so under a new charter, and thus, the TC was

founded and construction began in 1879. The Brazos River was bridged 25

miles north of Ross in January, 1880 and the TC's tracks reached the new town of Morgan

by April. Beyond Morgan, the line continued mostly west to

Dublin. Several miles beyond, the tracks began a

gradual curve to the northwest on an alignment that appeared to be headed

straight to the town of Eastland. There was no doubt among Eastland's populace that their

city would

host the crossing; it was the county seat and the largest

town in the area. The TC came

within five miles of Eastland, but it passed south of town and crossed the T&P

instead near the tiny hamlet of Red Gap about ten miles west. The citizens of Eastland

were not happy. Most likely, the TC had quietly purchased land near Red Gap

after surveying the route options, long before construction reached the

vicinity, giving them control over town lots and the depot site. The T&P

obviously had an easement near Red Gap and it may have owned some ROW land, but

it's unlikely they owned much else. In open country, the second railroad to a

crossing always had the advantage when it came to buying land for a town. They

could adjust their route as necessary to cross where it made the most sense.

Although they were building to the same location, there was no

"race" to reach Eastland County on the part

of the T&P and the TC. The T&P was more concerned with trying to reach El Paso

as quickly as possible. The Dallas Daily Herald

of July 29, 1880 reported that T&P grading crews had already gone "...sixty miles

beyond the end of the track..." which was the Brazos River at the time.

This would place the graders at Red Gap or perhaps a few miles beyond in early

summer. The Texas Central, by contrast, was laying track between Morgan and

Dublin in early summer, far from Eastland County, and its grading crews were

still in Comanche County to the south. By mid November, the T&P

tracks were at least seven miles beyond Red Gap, less than twenty miles from

Baird. The TC tracks appear to have reached Red Gap in early 1881, two or three

months after the T&P went through. The TC called it "Cisco",

named for an H&TC investor, John Cisco. "Cisco" appeared in newspaper

reports as early as November, 1880, most likely because TC construction plans

used that name. The TC was hiring companies to do grading, bridge work and track

laying on various segments. For bidding purposes, the companies had access to

the TC's plans, hence location names used by the TC leaked into the public

domain.

After the TC crossed the T&P at Cisco, construction continued 33 miles farther

north to Albany, where the first train rolled into town on December 20, 1881.

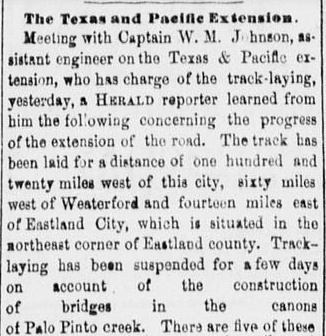

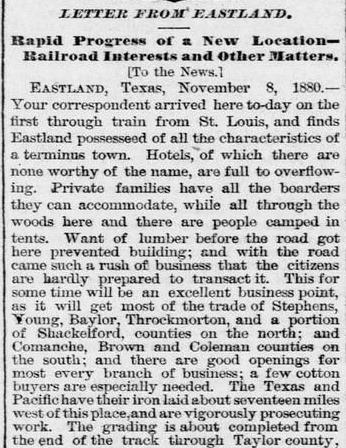

Above Left to Right:

Progress of the Texas & Pacific toward Eastland County: Dallas Daily Herald, July 29,

1880;

Dallas Daily Herald,

September 11, 1880;

Brenham Weekly Banner, October 21, 1880;

Galveston Daily News, November 11, 1880.

The T&P tracks reached the Brazos in July, 1880, by which time the grading teams were operating sixty miles farther west, about where Red Gap was locataed. A temporary bridge over the Brazos was being used to move construction trains to the west bank while the permanent bridge was under construction. By September, T&P's tracks were within fourteen miles of Eastland, and they reached the town in October on a "mile a day" construction pace. The first train from St. Louis to Eastland (via T&P connection at Texarkana) arrived on November 8, 1880. Every available accommodation was taken, so people "camped in tents" in the nearby woods. Grading had already been completed through Taylor County where Abilene would be founded with a town lot sale on March 15, 1881.

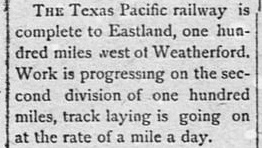

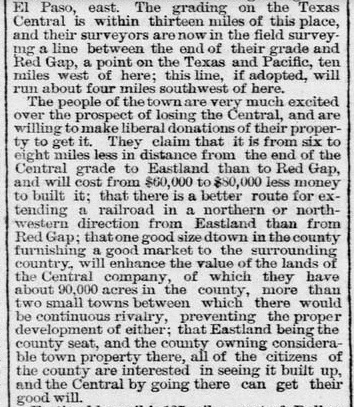

Below Left to Right:

Progress of the Texas Central toward Eastland County:

Galveston Daily News, November 11, 1880;

Clarksville Standard, November 19, 1880;

Dallas Daily Herald, December 17, 1880;

Ft. Worth Daily Democrat, April 22,

1881;

Galveston Daily News, May 25, 1881.

The TC's grading teams were reported to be within 13 miles of Eastland by November, 1880, and their decision to bypass Eastland for Red Gap was not going over well with the locals. Red Gap was a tiny hamlet, but with a crossing of two railroads, it was destined to grow, resulting in the accurate anticipation of "continuous rivalry" with Eastland. As the TC tracks reached Comanche County, due south of Eastland County, the name of the projected T&P crossing site, Cisco, was expressed publicly in the Clarksville Standard of November 19, 1880, quoting the Houston Telegram. Although the Dallas Daily Herald article of December 17th starts with odd phrasing..."got run over by the Texas & Pacific...", that was actually the good thing that happened to Eastland since it brought T&P's rails to town. The article then mentions "feverish excitement" in the county, but that turns out to be a bad thing, caused by Eastland being bypassed by the TC. The townsfolk of Eastland were most unhappy that their significant financial offer was only heard by a "deaf ear". By the spring of 1881, the name Cisco was in common usage replacing Red Gap, and in May, 1881, town lots were sold by the TC in Cisco, mistakenly quoted in the Dallas Gazette as being in Callahan County. The article notes that the T&P still used Red Gap as its station name. After winning the vote to become county seat in 1875, Eastland had to win again when Cisco residents forced another vote in 1881. Eastland won, barely, by 30 votes out of nearly 700 that were cast.

|

Left: The application for a Post Office at Red Gap (upper portion shown) was originally completed on March 29, 1878, and received by the Post Office Department in Washington, D.C. on April 19, 1878. "Red Gap" was later crossed out and "<illegible> to Cisco" was penciled in by hand. If the illegible word was "Changed", the notation would make sense, but it literally reads closer to "Chnatsi". The only other mark is a "C" written in pencil in the upper right corner where "R" is crossed out, a clerical practice to aid in alphabetical filing. Moving it to the "C" file suggests it was to be used in lieu of an original application for Cisco. Presumably the change occurred around May, 1881, when the town lot sale took place in Cisco. |

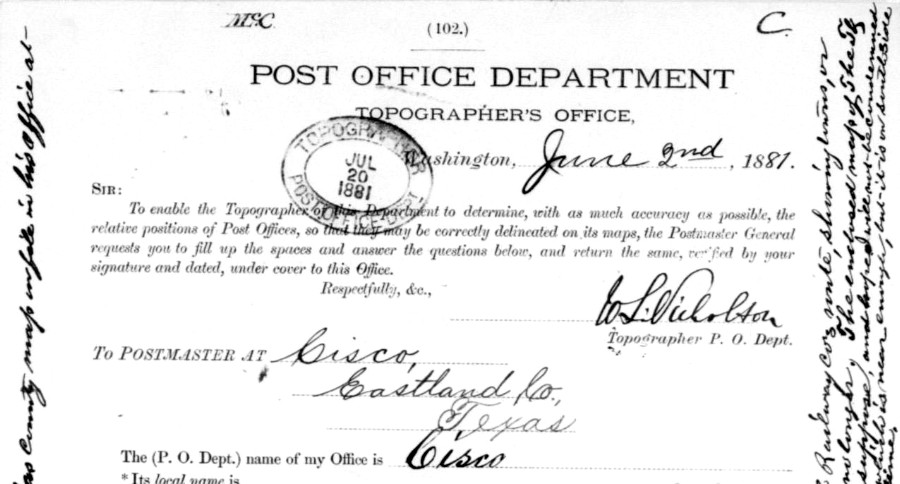

| Right: Each newly approved Post Office was contacted by the Topographer of the Post Office Department seeking to determine precisely where the new office was located. Many Post Offices were in remote areas that were difficult to access due to poor transportation and poor maps, so the Post Office made its own maps as necessary. On June 2, 1881, the Topographer's Office mailed a questionnaire to the "Postmaster at Cisco". The form was to be completed with geographic details of the new Post Office's location.The filled out form (upper portion shown) was completed on July 10, 1881, mailed, and processed in Washington, D. C. on July 20 by the Topographer's Office. A lengthy handwritten comment along the edge of the form says..."I have been waiting to get a map of the Texas Central Railroad Co's sent showing towns or stations on it, with P.O., but not getting it. Will wait no longer. The enclosed map of the T.C.R.R. will show and give some information I suppose, and hoped will not be condemned for sending it. I place Cisco where Red Gap is closed down, which is near enough, but it is on south side of T&P and leased out but will spread to north side in time. Mr. G. H. Hudelson our County Surveyor has county map info in his office at Eastland which is his P.O. also." (both documents from the National Archives) |  |

The T&P's rapid pace to the west through Eastland

County and beyond reflected their focus on reaching El Paso before Southern Pacific (SP) did. The same Act of Congress

that had granted T&P's charter had also authorized SP to connect with the T&P at

Yuma, Arizona. Six years after the charter was granted, the T&P was nowhere near Yuma,

so in 1877, SP kept building east on the previously

surveyed T&P route toward El Paso. SP's real objective was to create a

transcontinental route through Texas closer to both Mexico and the Gulf (substantially

south of T&P's congressionally sanctioned route) using

San Antonio, Houston and

New Orleans as waypoints. Rail baron Jay Gould, in control of the T&P at the

time, soon realized that SP's tracks would reach El Paso first and be well into Texas by the time

T&P's construction reached the vicinity. A deal was struck. SP gave the T&P

rights on its tracks into El

Paso; Gould gave SP all of the rights and franchises T&P had negotiated with

territories to the west and agreed not to build beyond El

Paso. The meeting point for the two railroads became the

new town of Sierra Blanca, 91 miles east of El Paso. SP construction crews

reached Sierra Blanca on December 6, 1881 (some sources say November 25, 1881)

and the T&P rails arrived on December 16, 1881. From there, SP continued

building east toward San Antonio, eventually completing what would become known

as the Sunset Route.

The T&P also had a charter from the State of

Texas

that granted twenty sections of land for each mile constructed. Using

acquisitions and construction, the T&P had managed to establish two parallel

lines between Texarkana and Ft. Worth (the "main" southern route through

Marshall, Longview and Terrell, and the northern

route through Paris and

Sherman.) The state land grant amounted to

five million acres for the tracks east of Ft. Worth, but 90% of the

land surveyed was west of Ft. Worth, and 75% was in a

vast, arid, unpopulated region between the Brazos River and El Paso. Because of

T&P's delay at Ft. Worth (which resulted in not meeting the terms of its state

charter), Texas refused to grant 6 million additional acres for the new

construction west to Sierra Blanca. The T&P finally reached El Paso on SP's

tracks which boosted its operations and it continued selling

its land to raise capital to retire its

construction bonds. But operations were expensive across the vast west Texas

track, and sales were slow because the sparsely populated land had little value.

Revenue from land sales combined with net income from operations was

insufficient for the T&P to be able to pay interest owed on its bonds; it went

into receivership in 1885.

The T&P's situation was unusual because it

operated a long track through a sparsely populated region and had not expected locally generated commerce

(particularly west of Ft. Worth) to carry the railroad's finances. The original investors had

been counting on transcontinental traffic with San Diego to subsidize operations.

Because they had not anticipated the construction delays that prevented the T&P

from achieving its transcontinental goal, they also did not foresee SP's Sunset Route

becoming established farther south. The T&P had tried (and

failed) in court to prevent SP from building east on the route T&P had surveyed from

Yuma to El Paso, but the T&P was penalized by its own delays.

The Federal charter had been granted in 1871, but after five years, the T&P

was only as far west as Ft. Worth, nowhere near El Paso let alone Yuma or San Diego. The

territories between California and El Paso wanted rail service as quickly as

possible and they were happy to provide SP with whatever legal provisions it needed to continue building east. The completion of the Sunset Route across

Texas (with a Silver Spike ceremony at the Pecos River on January 12, 1883)

meant that a significant percentage of traffic from the west coast would stay on

SP's rails and go

southeast at Sierra Blanca toward San Antonio and Houston rather than northeast

to Ft. Worth on the T&P (a situation that remains true today, with both

routes owned by Union Pacific.) Pacific imports and west coast goods needed Gulf ports; the Panama

Canal was more than thirty years in the future.

The T&P owned a huge amount of

Texas land, nearly 4 million acres at the time of bankruptcy. Unfortunately, the

land was almost worthless, and it certainly would become completely worthless if a court

attempted to liquidate that much land. There was simply no market.

The T&P still had substantial promise for

overhead traffic since it was potentially an important link in a national transcontinental

line, the shortest route between Los Angeles and St. Louis at the time. With

these issues in mind, the bankruptcy judge approved a plan to delay the

disposition of the T&P's land. Instead, the T&P's bondholders were given

shares in a trust, the Texas Pacific Land Trust (established February 1, 1888),

that would own and sell land as prices and opportunities warranted. Land prices

were expected to rise as the T&P continued operations, no longer saddled with a crushing

debt load. Land sales

at higher prices would produce a nice revenue to the Trust that would be returned to the Trust's

beneficiaries through dividends. The assets of the Trust were the

3,450,642 unsold acres owned by the T&P, plus the T&Pís equity in contracts on 381,234 acres

that had already been sold. The beneficiaries of the Trust were the T&P's bondholders,

each receiving "proprietary interest"

in the Trust in proportion to debt owned. To make this scheme work, these

"proprietary interests" could be

bought and sold on the open market. The Court vested three Trustees with legal

title to the land, and they were charged with the duty to hire staff to execute

the Trust's mission of selling the land and producing revenue from unsold land

(mostly through farming and grazing leases.) The

Trust declaration required the Trustees to be paid a fixed and perpetual stipend

of $2,000 per year, plus an extra $2,000 annually to the Trustee chosen as

Chairman, a total of $8,000.

|

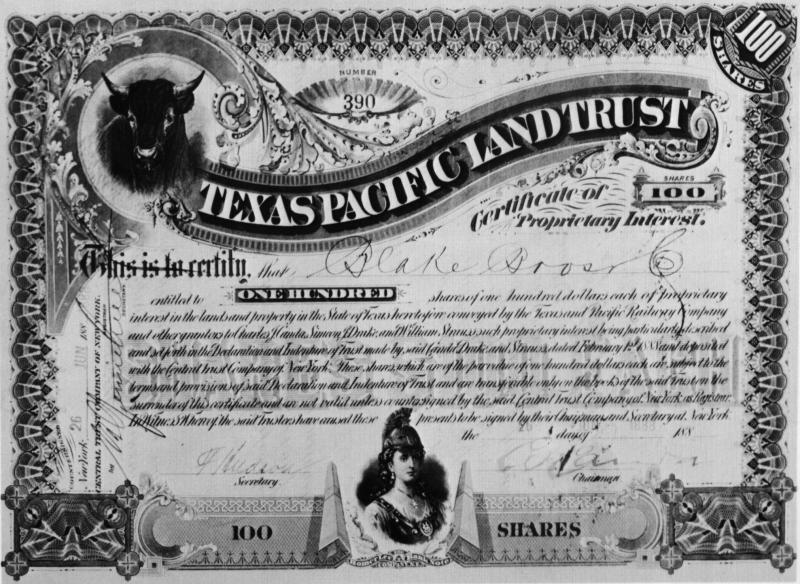

The judge created a

100-share "Certificate of Proprietary Interest" in the Trust, issued to each T&P creditor in proportion

to the debt they owned. On June 27, 1888, the

Trust's 100-share certificates were listed on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) under

stock symbol TXL. Trust revenue paid

office and salary expenses, property taxes, and the annual stipend to the Trustees.

The Trust issued dividends from the remainder. Unlike companies that

pursue growth and profit strategies, the Trusts assets diminished with

each land sale. To counteract this downward pressure on its share price,

the Trust began buying shares on the open market in 1900 and canceling those

certificates, reducing the shares outstanding (thus, spreading dividends

over fewer shares.) In 1915, the Trust began oil and gas rights leasing,

and by 1931, there were 56 wells on Trust land generating $246,078 in

royalties. In 1926, the certificates were split 100:1 so that individual

shares could be traded. In 1954, TXL Oil Co. was created and spun-off to

Trust shareholders, owning most of the Trust's mineral rights as its

primary asset. The oil company took the TXL stock symbol; the Trust's

new stock symbol became TPL. In April, 1962, TXL Oil Co. was acquired

and merged into Texaco, Inc. (now part of Chevron.) By 1980, each

original 100-share Trust certificate equated to 600 TPL shares (not

counting the value of TXL stock already spun off.) In January, 2021, the Trust became a Delaware C-Corp.,

Texas Pacific Land Corp., still using the TPL stock symbol. Certificate No. 390 (left) was worth $700 when received by Capt. Joseph DeLamar in 1896 as partial payment for a debt owed by Joseph Decker, Esq. The certificate was lost until 1979 when it was discovered in the archives of Wells Fargo Bank of San Francisco. When courts awarded ownership of the certificate to Capt. DeLamarís heir, Miss Alice DeLamar, the value of the certificate was $5.7 million. (image courtesy Texas Pacific Land Trust, 1987 Annual Report) - NYSE midday TPL price on December 31, 2021: $1,244.98 per share |

Like the T&P, the TC discovered that operating a

lengthy rail line through sparsely populated territory was financially

challenging. And like the T&P, it entered receivership in 1885. After

operating under Court supervision for six years, the TC was sold to a committee

of bondholders. An incomplete TC northeast branch toward

Paris was sold off and

became the basis of the Texas Midland Railroad. The TC's northwest branch, from Ross to Albany

via Cisco,

was then deeded by the bondholders to a new Texas Central Railroad Company in

January, 1893. The new company added tracks from Albany to Stamford (1900), Stamford

to Rotan (1907), and De Leon to Cross Plains (1911.)

In 1910, the Missouri - Kansas - Texas (MKT, "Katy") Railroad acquired 90% of

the stock of the TC. They did not, however, take control of the company until

May 1, 1914 when the TC was leased to the Katy's Texas-based subsidiary. This

enabled the Katy to comply with state law regarding railroad ownership since it was not a Texas corporation. The Texas Central name continued to be used,

but "MKT" and "the Katy" came into common parlance as TC operations

continued.

Although Cisco and Eastland had a vigorous rivalry during the three decades

after their founding (with Ranger, unincorporated, much smaller and mostly ignored), service by two

railroads gave Cisco a distinct advantage. By 1910, Cisco was roughly three

times the size of Eastland. This would soon change. In 1915, the Texas Pacific Land Trust's first oil

and gas lease, near Breckenridge in Stephens County twenty-four miles northwest

of Ranger, earned the Trust $175 in revenue. The first producing well on Trust

land began generating royalties in 1921 in the Breckenridge oil field that had

been discovered in 1916 (but Trust land ultimately had limited oil production in

Eastland and Stephens counties; its major production was in the Permian Basin

farther west.) On October 21, 1917, the McClesky No. 1 well at Ranger struck oil

and began producing 1,700 barrels per day, inaugurating an oil boom at Ranger. In 1918, a major well at Breckenridge

produced a similar boom. An oil field also developed at Desdemona, a community 16 miles southeast

of Ranger. The census figures show the enormous population growth in

the major towns of Eastland County triggered by the regional oil boom; some histories claim that Ranger had peaked

at perhaps 30,000 residents.

| Town | 1910 Census | 1920 Census |

| Cisco | 2,410 | 7,422 |

| Eastland | 855 | 9,368 |

| Ranger | not incorporated | 16,205 |

To serve the rapid economic growth and get oil moving out of

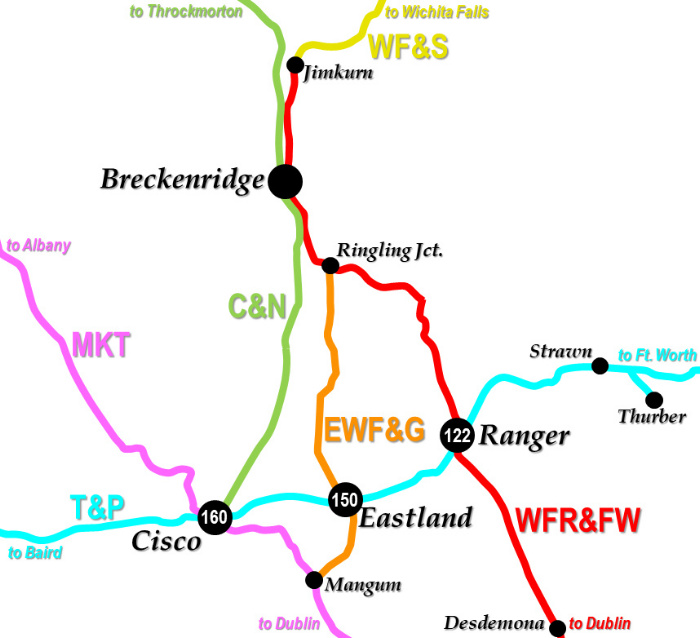

the fields by rail, three railroads were chartered:

The Cisco & Northeastern (C&N) Railway

was chartered in early December, 1918 to build seventy miles between Cisco and

Graham. It completed 28 miles from Cisco to Breckenridge in October, 1920. The C&N became owned by the T&P in 1927 but operated

as a subsidiary. The line was extended 37 miles northwest from Breckenridge to Throckmorton in

1928.

The

Wichita Falls, Ranger &

Fort Worth (WFR&FW) Railroad was chartered in September, 1919

and built 67

miles between Dublin and Breckenridge via Ranger. In 1921, the WFR&FW built nine

miles farther north from Breckenridge to a junction known as Jimkurn. There, it

connected to the Wichita Falls & Southern (WF&S) Railroad which was building

south that same year from Newcastle, where the WF&S tracks from Wichita Falls had

stopped in 1908. The WF&S had rights on the WFR&FW from Jimkurn into Breckenridge.

The

Eastland,

Wichita Falls & Gulf (EWF&G) Railroad (briefly and

unofficially known as the Ringling, Eastland & Gulf) was chartered in late

December, 1918,

ostensibly to build

96 miles between May (near Brownwood) and Newcastle. Investors included Ben Munson (founder of

Denison) and Richard Ringling (of the famous circus

family.) In 1920, the EWF&G completed 27 miles of track between Mangum (where it

connected with the MKT) and a location known as Ringling Jct., south of

Breckenridge, where it terminated into the WFR&FW.

|

Left:

In 1901, the Railroad Commission of Texas (RCT) was given authority by state

law to regulate crossings of two or more railroads, regardless of whether they were "at

grade" or "grade separated". Until safety systems (e.g. gates,

interlockers, signals, derails) were installed for crossings "at grade",

all trains had to stop before proceeding over a diamond. Although the crossing

of the TC and T&P in Cisco had existed since 1881, RCT did not consider it a

priority to be interlocked. The reason was simple; Cisco was the largest town in

Eastland County as well as a water stop for steam engines. Every train into

Cisco from any direction stopped near the crossing at either the union passenger

depot or a freight depot. This

satisfied the need to stop before proceeding across the diamond, hence an interlocker

would have added no operational value. The regional oil boom spawned three new railroads which created two additional crossings of the T&P, at Eastland and Ranger, respectively. Unlike Cisco, RCT required an interlocker at Ranger soon after the crossing became established. Yet, it was not until January 20, 1926 that a cabin interlocker at Ranger, known as Tower 122, became operational. The next T&P crossing to be interlocked was at Eastland when Tower 150 was commissioned on May 13, 1929. It was among many cabin interlockers installed in the late 1920s at locations long overdue, where railroads may simply have resisted making the investment. Cabin interlockers required less capital to install, and they incurred no labor expense to operate because the controls were set by train crew. Cabins made sense for locations where the recurring costs of a manned tower could not be justified. An interlocker at Cisco, Tower 160, began operation on August 13, 1930. This was not a cabin interlocker; it was an electric plant and was likely controlled from the nearby union depot (thus the interlocker required no extra staffing because it was operated by depot personnel.) Before the oil boom, there had been a coal boom east of Ranger. The T&P built a short branch to Thurber in 1888, and coal continued to be mined in large quantities until the oil boom hit. Railroads began to shift their locomotives to oil, and it led to the demise of Thurber by the early 1930s. T&P's branch was abandoned in 1942. |

|

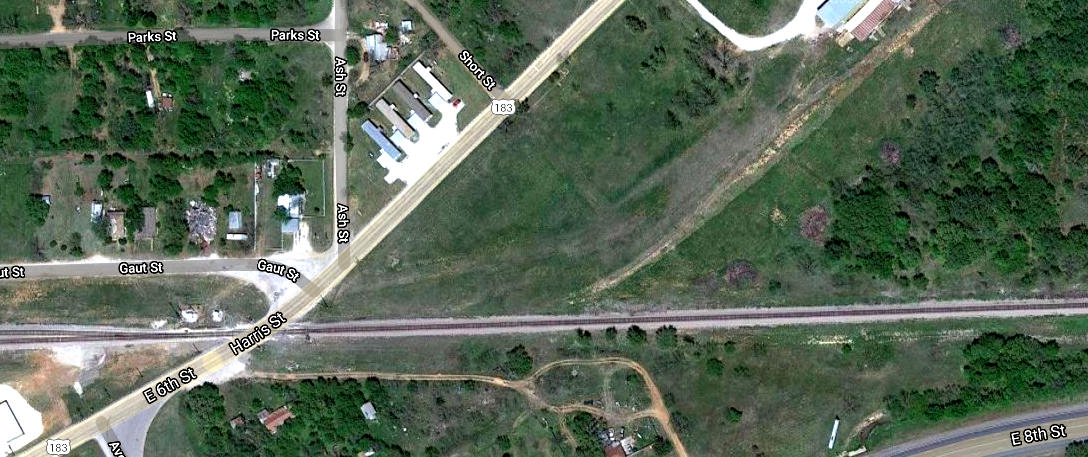

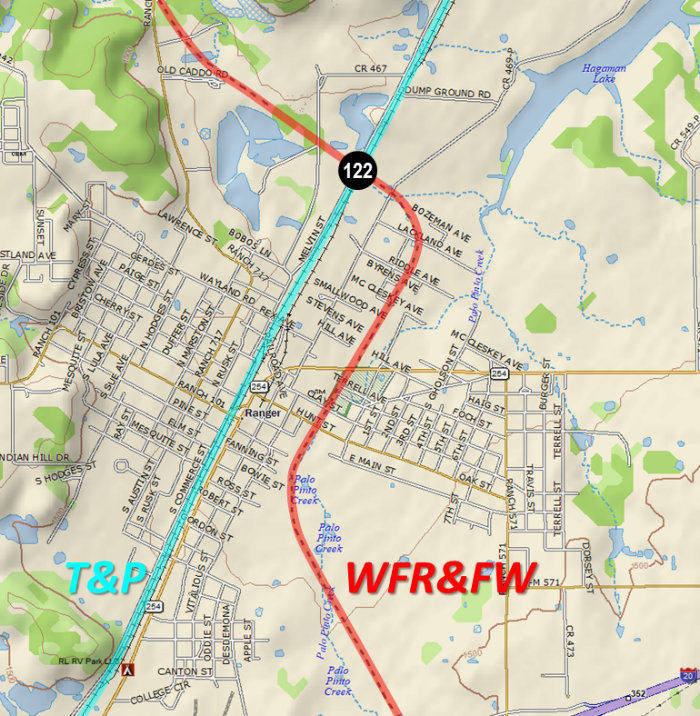

Left: This annotated

Topo USA map shows the WFR&FW tracks on the east side of Ranger,

crossing the T&P about a mile north of the center of town. On

February 20, 1920, RCT ordered the WFR&FW to install an interlocker at Ranger.

Immediately, the T&P sought and obtained a court injunction prohibiting

execution of RCT's order. Why? The best guess is that T&P did not want the

recurring cost of a manned tower, and an inexpensive cabin interlocker

was not yet an option (the first official cabin interlocker would not be

commissioned by

RCT until three years later at Hyatt.) With the interlocker delayed

by the injunction, the crossing was still uncontrolled when the WFR&FW went into receivership

in December, 1921. On April 30, 1925, T&P wrote a letter to RCT requesting a revision to the interlocking order for Ranger, asking that a cabin interlocker be authorized "in view of the financial condition" of the WFR&FW (implying that the original order was not for a cabin interlocker.) Finally, on January 20, 1926, a cabin interlocker was installed, designated Tower 122 by RCT (the white building in Barriger's 1940 photo is probably the original cabin.) A cabin interlocker was a trackside hut that housed the mechanical plant and its controls. It was operated by crewmembers from trains on the lightly used line, in this case, the WFR&FW. When they needed to cross the T&P, their trains stopped near the crossing and a crewmember would enter the hut to change the signals to allow their train to pass over the diamond. This also signaled trains on the T&P that the crossing was occupied. Once the train was across, the crewmember would reset the signals for unrestricted movement on the T&P. Unless a T&P train happened to approach the crossing while it was occupied, T&P trains would always have a "Proceed" signal to cross without stopping. By the time of Barriger's photo, better electronics allowed the controls to be remoted to the metal post with the mounted box seen in the foreground across from the home signal post (of which there are many other examples.) Inside were pushbuttons and indicators that controlled the semaphores via the interlocking plant. A similar post and box for southbound trains is visible in the distance. Controls were not needed along the T&P tracks since their crews didn't normally operate the interlocker. Two months after Tower 122 began operating, the WFR&FW's receivership ended, and soon thereafter, it was acquired by the WF&S. The WF&S was abandoned in 1954, including the former WFR&FW tracks through Ranger. On January 21, 1955, T&P wrote a letter to RCT explaining that... "As a result of the retirement of the Wichita Falls, Ranger & Fort Worth railway tracks at Ranger, Texas, Interlocking No. 122, which formerly protected the crossing"..."has been retired." |

|

Left:

This snippet from the 1929 Sanborn Fire Insurance map of Ranger shows

the crossing of the WFR&FW (horizontal) and the T&P (vertical). Note that the

second exchange track (visible in top photo) did not yet exist. Below: At the crossing, magnification shows a cabin interlocker which was described by the cartographer as a "R. R. Switch Ho." (railroad switch house.)  |

Below: There's not much to see with satellite

imagery at the former Tower 122 crossing. Portions of the exchange track

in the north quadrant are visible, but the east exchange track

has been obliterated by cultivation. The former T&P tracks remain busy,

now owned by Union Pacific. |

Above Left: On October 1,

1940, John W. Barriger III took this photo of his special RFC inspection train parked adjacent to the WF&S depot in Ranger.

Above Right: the T&P depot in Ranger, photographed on

April 26, 1982 by Don Watson

Below

Left: The RFC inspection trip John W. Barriger III made along

the WF&S on October 1, 1940 stopped in Breckenridge near the WF&S depot as it

headed south. Barriger took this photo, most likely from the rear platform of

his business car, facing north toward Wichita Falls where his trip had

commenced. Below Right:

a similar Google Street View from 2013, with the former depot still standing

The next interlocker to be installed in Eastland County

was for the EWF&G crossing at Eastland. By charter, the EWF&G was to build

between May and Newcastle. May was in Brown County, the next county due south of

Eastland County, and was the northern terminus of the Brownwood North & South

Railway, an 18-mile line from Brownwood completed in 1911. Connecting at May

would create a line to Brownwood, where Santa Fe had a main line and significant

operations. Newcastle, site of a major coal mine, was in Young County, two

counties north of Eastland County, and was the terminus of the WF&S main line

out of Wichita Falls. The EWF&G construction, however, began at neither end,

choosing instead to start in the middle, six miles south of Eastland at the

community of Mangum. Construction materials could be shipped to Mangum by rail

because it was on the TC line south of Cisco.

In 1920, the

EWF&G completed 27 miles of track north from Mangum through Eastland to Breckwalker,

a new town several miles south of Breckenridge,

named for a wealthy local oilman, Breckenridge "Breck" Stevens Walker. Breck

Walker was a member of the EWF&G Board of Directors, but the town was actually

named by the WFR&FW which had built through the area a few months earlier. The

EWF&G terminated into the WFR&FW at a location just over a mile east of Breckwalker,

and had rights on the WFR&FW into Breckwalker. A 1934

Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) valuation report states that the EWF&G had trackage rights on the WFR&FW

between "Ringling Junction" and Breckwalker. RCT's 1939 Annual Report described

the trackage rights as between "Breckwalker Junction" and Breckwalker.

Barriger opted to call it "Ringling Jct." when annotating his photograph

(below.) Shortly after making its connection to the WFR&FW, the EWF&G was leased by the

WFR&FW for a year. When the lease lapsed, the EFW&G returned to independent

operation. It never built any additional tracks and was abandoned in 1944.

|

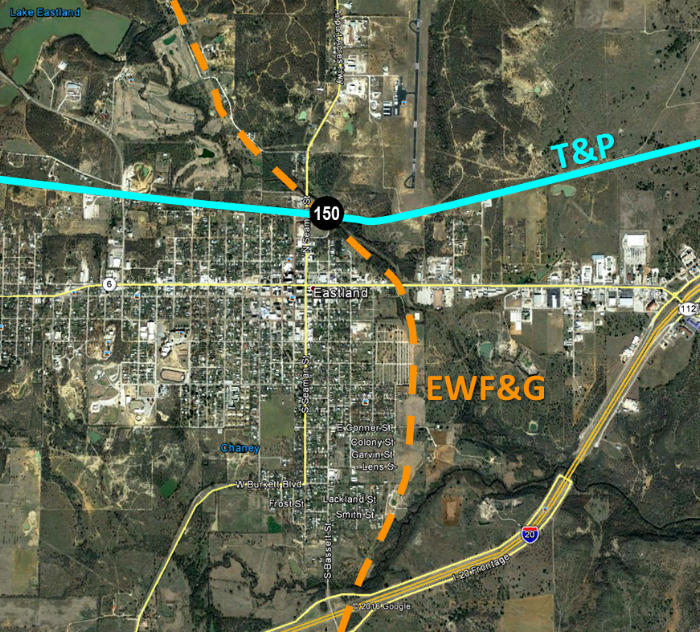

Left: This annotated Google Earth image of Eastland

shows that the EWF&G came up the east side of town and crossed the T&P

north of downtown on a northwest heading. Below:

There's no longer any evidence that the EWF&G ran beside

and southwest of the North Fork Leon River, crossing the T&P just west of T&P's

bridge over the river. (Google Earth 2019)

Bottom: T&P depot at Eastland (H. D. Conner

photo)  |

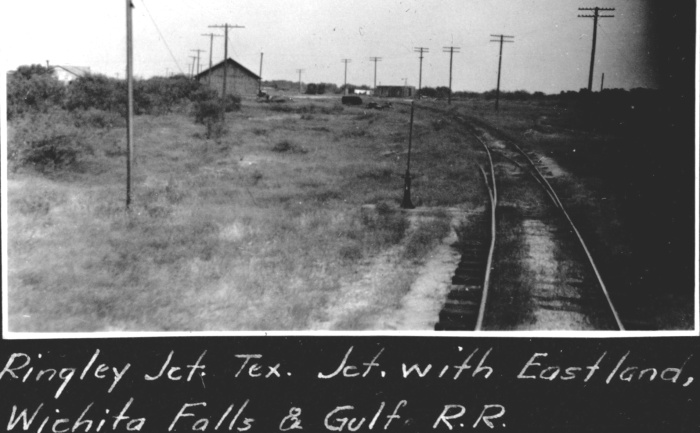

Below Left:

Annotated imagery from 1960 ((c)historicaerials.com), about six years after the WF&S was

abandoned, shows the location of Ringling Jct. at 32 39 52N, 98 49 57W. The

EWF&G had been removed sixteen years earlier. Below Right:

John W. Barriger III snapped this photo at Ringling Jct. on October 1, 1940

during his RFC inspection trip. As shown by the historical imagery below left,

the WF&S tracks were on a tangent line through Ringling Jct. Thus, in Barriger's

photo, the curvature of the track and the divergence of the utility poles to the

right suggest that Barriger is standing beside the tracks of the EWF&G facing northwest

toward its switch onto the WFR&FW (WF&S tracks by this date.) Barriger's train was headed to

Ranger so it's unlikely that it has taken the EFW&G connection.

|

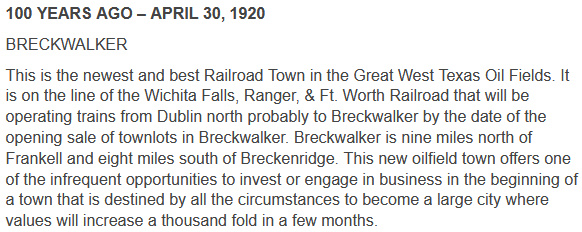

Left:

There wasn't much to see in Breckwalker, but John W. Barriger III photographed

it anyway during his RFC inspection trip on October 1, 1940, shortly before

stopping at Ringling Jct. The view is along

the WF&S tracks (built originally by the WFR&FW) north toward Breckenridge. When the EWF&G tracks

terminated into the WFR&FW at Ringling Jct., the EWF&G obtained trackage rights

for the mile or two into Breckwalker and ended there. The occupied siding served to facilitate railcar exchange as the EWF&G did not have rights into

Breckenridge. Below: On April 30, 2020, the Olney Enterprise reprinted this description of the new town of Breckwalker that had appeared in their newspaper 100 years earlier. That part about "a large city" never quite panned out.  |

The first railroad chartered in reaction to the oil boom in Eastland and Stephens counties was the Cisco & Northeastern (C&N) in early December, 1918. Officially, it was to build from Cisco to Graham in Young County, north of Breckenridge. In reality, construction stopped after the 28 miles from Cisco to Breckenridge were completed in 1920. Although the C&N connected to the T&P with exchange tracks along the north side of the T&P main line, its tracks at Cisco crossed neither the T&P nor the MKT (TC). Thus, it was not directly involved in the interlocker installed at Cisco (although by the time the Cisco crossing was interlocked in 1930, the C&N had already become a T&P subsidiary, in 1927.) The C&N extended its line 37 miles north from Breckenridge in 1928, choosing to go north to Crystal Falls (about a mile west of Jimkurn) and then northwest to Throckmorton, instead of going northeast to Graham. By that time, Graham was already served by two railroads including the WFW&FR/WF&S route that connected at Jimkurn. The C&N ultimately ceased operations in 1942, a victim of pipelines and a reduction in oil-related commerce.

|

Left: Both the C&N and the WFR&FW had tracks into Breckenridge, but they did not connect, creating consternation for many shippers and businesses. Often, distant companies would ship products to Breckenridge that arrived on the wrong railroad, requiring local drayage to move the goods. Businesses asked the ICC to mandate a connection. One example was a gasoline plant on the C&N owned by a company that had a retail gasoline sales facility on the WFR&FW. When a tank car was emptied at the sales facility, it took three days, rather than three hours, to move the tank car back to the gasoline plant. The C&N wanted the connection and offered to pay 63% of the cost. The WFR&FW claimed the connection would cause a 30 to 50% reduction in revenue, hence it refused the request. That claim appears to have been the determining factor in the case. Regional ICC examiners recommended dismissing the complaint, which the ICC did on March 4, 1926. At the time, the WF&S had rights into Breckenridge from Jimkurn and was working to acquire the WFR&FW. The WF&S later built a connection to the C&N tracks in Breckenridge, but it may have been after the C&N's demise in 1942. (ICC archives) |

While the crossing at Cisco had existed for fifty

years, nearly thirty of them after the 1901 interlocker law, operations through

Cisco had never motivated the railroads to undertake the expense of installing

and operating an interlocker, nor had RCT mandated one. Whether the T&P and TC

eventually pursued one on their own is unknown, but by 1930, RCT appeared to be

in the midst of a major effort to order interlocker installations at places they

believed should already have one (even if the railroads didn't necessarily

agree.) In 1929 alone, seventeen new interlockers were commissioned. Three more

were commissioned in 1930, including Tower 160 at Cisco on August 13, 1930. Ten

more were under construction at the end of 1930. Overall, thirty interlocker

were

commissioned in 1929 - 1931, about one fifth of all active interlockers. It seems likely this was driven by

RCT, not a random coincidence. Of these thirty, only two, at

Mauriceville and Pierce

Junction, have tower numbers that suggest the applications were considered

by RCT earlier in the decade but their commissioning dates were delayed for

some reason. The remaining 28 probably resulted from an effort by RCT to step up

the pressure and order every crossing controlled in some way. A large majority

of these were cabin interlockers which were substantially less expensive to

install, maintain and operate.

But Tower 160 was not a cabin interlocker.

It is listed in RCT documentation as a 19-function electrical interlocker

operated by the T&P, with the MKT named as the other participating railroad.

Cabin interlockers were strictly mechanical plants (at least, as of 1930), and

the largest cabin interlocker ever approved by RCT only had twelve functions (a

home signal, distant signal and derail in each of four directions.) Nor is there

any evidence that Tower 160 was a typical 2-story manned tower. The staffing

expense alone would be enough to deter such a design for a crossing of two

railroads where one of them, the MKT, probably had at most a couple of trains daily

in each direction. The fact that the interlocker was an electric plant meant

that its controls could be remoted easily into a nearby facility.

Operating an interlocker from a depot was a fairly common solution, e.g.

Tower 15 and many others. The Cisco Union Passenger

Station was near the crossing, and

the interlocker controls were almost certainly located there, operated by staff who

were on duty for other purposes (often the telegraph operator, who was

knowledgeable of the schedule since the job included taking train orders to be

passed to approaching trains.) If the station did not have 24/7 staff, the

signals would be left lined for unrestricted movement on the T&P. Had an

unfortunate Katy train approached the crossing after hours, there would have

been procedures for getting across the diamond

(beginning with contacting the unlucky employee who was "on call".) Although the

C&N was not officially involved with the interlocker (and by 1930, they were

a subsidiary of T&P anyway), their trains sometimes

accessed T&P tracks and they followed interlocker signals and T&P timetable rules when doing so.

A 1954 T&P employee timetable shows that by that date, control of the Cisco

interlocking had been transferred to T&P's dispatching office at Baird. The

timetable also cautioned that because the interlocking was very close to T&P's

siding tracks at Cisco, a dispatcher granting "track and time limits"

authority to a work train for freight car switching had to specify whether or not the grant included access through the

interlocking. If such interlocker access was granted, trains could ignore

interlocker "Stop" signals and could back through the crossing as necessary for switching

purposes.

In 1967, the Katy abandoned the TC line

through Cisco and the Tower 160 crossing was removed.

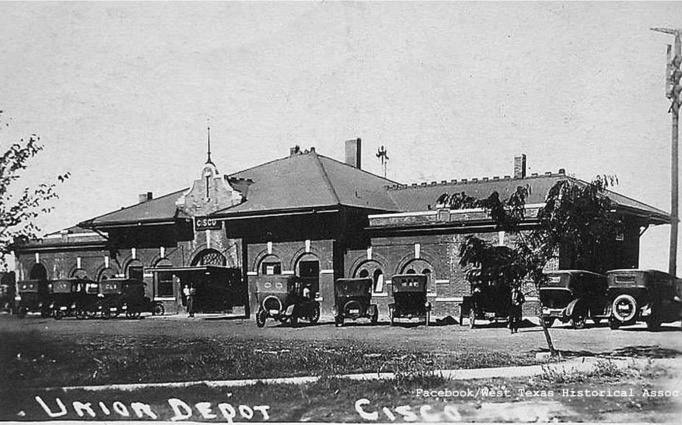

Above Left:

This annotated Google Earth image shows the two rail lines that crossed at Cisco.

They both arrived before the town existed, thus the

town grew up around them although the main part of town remained south of the T&P

tracks (perhaps because Red Gap was north of the tracks.)

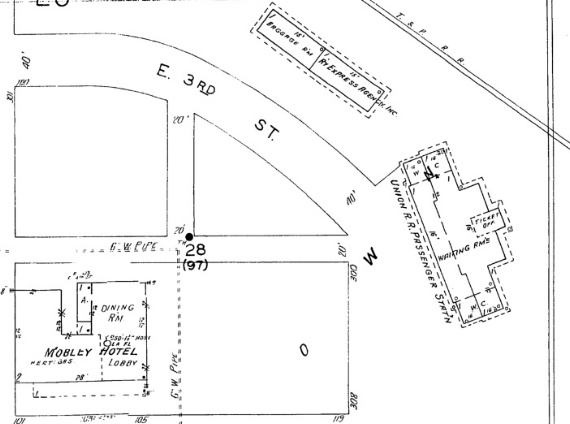

Above Right: The Union

Passenger Station was on the southwest side of the crossing as was the Mobley Hotel. In 1919, a young,

World War I veteran from New Mexico came to Cisco to make his

fortune in the oil boom. Unable to strike a deal to buy a bank, he

bought the Mobley Hotel instead, and thus, Conrad Hilton became famous for

Hilton Hotels instead of Hilton Banks.

Above Left: Cisco Union Depot

in 1922 (West Texas Historical Society)

Above Right: A yellow caboose sits beneath a tree on the former

Katy (TC) ROW angling through Cisco just south of the T&P tracks. The Tower

160 crossing

would have been visible in the top middle of the image. Slab remnants and the outline of the

union depot's foundation are visible in the center of the image. Below:

This Google Street View image shows the caboose with no tree towering over its

north end, located in a fenced town park, the same fence that presumably

outlines the caboose area in the image above. The entire area between the tracks

and 4th St. has been cleared down to the dirt. Unfortunately, Google claims

February, 2013 as the date of the Street View image below and April, 2019 as the

date of the satellite image above. This seems odd since the outline of the depot

foundation and various slab remnants don't appear in the 2013 image but they do

appear in the 2019 image. If the dates are accurate, the clearing activity shown

below must have continued scraping dirt until the slab remnants and foundation

of the depot were uncovered. To add to the confusion, see

this December, 2021 Street View image.

Above: The Katy freight depot

in Cisco cleaned up nicely between 2010 (left,

Doyle Davis photo) and 2017 (right,

Richie Morgan photo.) The depot is beside the TC ROW (in the foreground) about

750 ft. south of the yellow caboose.

|

Left:

This 1915 track chart of Cisco from the Office of Chief Engineer of the Katy

railroad shows that by that date, there were connecting tracks west of the Katy,

both north and south of the T&P. (Ed Chambers collection)

Below: Union Station is

visible in this aerial image of the Tower 160 crossing from 1965, two years

before the Katy tracks were abandoned. ((c)historicaerials.com) |

Below: The C&N connection to the T&P at Cisco was on the

east side of town, adjacent to what is now the U.S. 183 (Harris St.) grade

crossing. To the northeast, U. S. 183 to Breckenridge sits directly atop the C&N

ROW in a few places. At the time the highway was built, it was State Highway 187. State

Highway 6 running northwest out of Eastland intersected Highway 187 about 9 miles

northeast of

Cisco, and the two highways shared 19 miles of roadway north into Breckenridge. At

Breckenridge, Highway 6 continued north to Throckmorton. In early 1952, highway engineers determined that

the locals preferred to

travel between Cisco and Throckmorton via Breckenridge using Highways 187 and 6,

which

had better surfaces and fewer curves than U. S. 183, which routed between Cisco and

Throckmorton via Albany (sharing the U. S. 283 roadway north of Albany.) In May,

the Highway Commission directed that the designations of Highway 187 and

the segment of Highway 6 into Throckmorton be

eliminated and renamed U. S. Highway 183. So that Highway 6 could resume its

northward route out of Throckmorton, it was redefined to go due west out of

Eastland to Cisco (sharing the U. S. 80 roadway) and then north

to Albany and Throckmorton via the former Highway 183 route. The section of Highway 6

that had run between

Eastland and its junction with the former Highway 187 was re-designated as a

farm-to-market road, but it has since been changed to State Highway 112.