Tower 61 - A Crossing of the Texas & Pacific Railway and the Missouri, Kansas & Texas Railway

Tower 123 - A Crossing of the Texas & Pacific Railway and the Jefferson & Northwestern Railway

|

Left:

This undated photo from Ed Joseph courtesy of the Jefferson Carnegie

Library shows Tower 61 in the west quadrant of the crossing of the

Texas & Pacific Railway and the Missouri, Kansas & Texas Railway in

Jefferson. The photo had previously been annotated with "T.P. Ry"

(left of diamond) and "MK&T" (between the rails

in the shadow of the tower.) Special thanks to the library staff for

locating this photo! Below:

The cabinet housing the automatic interlocker that replaced Tower 61

sits across the diamond from the tower site, beneath an overpass that was under

construction in 1956. (Peg Brown collection) |

Jefferson was founded in the early 1840s as a navigable

river port on Big Cypress Bayou. The bayou benefitted from elevated water levels

in Caddo Lake caused by the Great Raft of the Red River restricting water flow

out of the lake through tributaries that fed the river. By the 1850s, Jefferson

had become one of the largest inland river ports in the U.S. with steamboats

regularly arriving -- 226 in 1872 -- from diverse locations including St. Louis

and New Orleans The trade through Jefferson -- the majority of which was cotton

-- increased its population and made it an attractive location for a railroad.

Prior to the Civil War, the Memphis, El Paso and Pacific Railroad did some

grading in the Jefferson area. After the war, its remaining assets were acquired

by the Texas & Pacific (T&P) Railway which built a line through Jefferson

between Marshall and Texarkana in 1873.

About that same time, the East Line and Red River (EL&RR) Railroad was

chartered as a narrow gauge line by Jefferson business interests. The plan was

to build west to McKinney on the Houston & Texas Central Railroad, a town 42

miles south of Denison where a Red River rail

bridge built by the Missouri, Kansas & Texas (MK&T, "Katy") Railroad had just

opened. Jefferson's

civic leaders were concerned that the rapid, post-war expansion of railroad

construction in Texas would derail trade through its river port, particularly in

the summer months when the water level sometimes dropped low enough to prevent

steamboats from making the trek up from Caddo Lake. The theory

behind the EL&RR was that Midwest commodities southbound across the Red River bridge would

opt for a McKinney to Jefferson routing to be forwarded to New Orleans through Jefferson's

river port. Finances forced the EL&RR to cease construction upon reaching

Greenville in 1880, 32 miles short of McKinney.

| A few months earlier, in December, 1879,

rail baron Jay Gould had been elected President of the Katy, the result of a lengthy plan hatched in 1873 that

succeeded in getting Gould's henchmen into the executive ranks of Katy

management. Gould had little ownership interest in the Katy, he was merely its

President. To ensure his continued control, Gould leased the Katy in December,

1880 to Missouri Pacific (MP), a large Missouri-based railroad that he

controlled and in which he had a large ownership position. As Gould planned an

expansion of the Katy deep into Texas, he intended to use it to move long-haul

traffic to and from MP. As a result of accounting and operating policies tilted

heavily toward MP, its stockholders (mostly Gould) would reap the benefits of

the Katy lease and the Katy stockholders would not.

In 1881, Gould directed the Katy to buy the EL&RR and complete the

remaining 32 miles of narrow gauge track to McKinney as originally

planned. This segment of the EL&RR was converted to standard gauge in

1887; the remainder was converted in 1892. While taking over the Katy, Gould also sought control of the T&P. Having completed its Texarkana - Marshall line through Jefferson, the T&P had begun building west to El Paso. It had reached Ft. Worth, but was unable to build farther west for lack of funds. This gave Gould an idea; he created a construction company and offered to build the T&P line west of Ft. Worth in exchange for a combined $40,000 in T&P stock shares and bonds for each mile completed. A deal was struck, and as construction proceeded west, Gould's ownership and influence over the T&P increased with each mile. In April, 1881, Gould formally took control of the T&P. In 1886, a new Texas Attorney General, James S. Hogg, was elected on a campaign to go after the railroads for various infractions, and he quickly began filing lawsuits. When all of the legal dust settled several years later, Gould was no longer President of the Katy (he'd been fired by its stockholders), the Katy was no longer under lease to MP, and the Katy's ownership of the EL&RR had been declared unlawful by the Texas Supreme Court, a ruling that forced the EL&RR into receivership, with its charter forfeited. State law in 1870 had granted the Katy permission to use its Kansas charter as the basis for crossing into Texas over their planned River River bridge, but under Gould's control, the Katy had proceeded to expand throughout the state. As the Katy lacked both a Texas charter and a Texas headquarters, the court ruled the expansion illegal. A new charter would need to be approved by the Texas Legislature. The new Katy charter was filed on October 28, 1891 and approved by the Legislature establishing the Missouri, Kansas & Texas Railway Co. of Texas, to be headquartered at Denison as a wholly-owned subsidiary of the parent Katy corporation. The Texas subsidiary would own many of the Katy's former Texas rail lines, but not the International & Great Northern (a large Texas railroad which Gould had acquired and transferred to the Katy), and not the EL&RR, which was still in receivership. The Legislature would not allow the Katy to own the I&GN, so they had little choice but to sell it back to Gould. As for the EL&RR, it was sold out of receivership in early 1892 to the newly chartered Sherman, Shreveport & Southern (SS&S) Railway owned by investors based in Greenville and Sherman. The SS&S extended the line 30 miles east from Jefferson to Waskom in 1900. A new state law in 1899 provided for another reorganization of the Katy in Texas. Among the details, the law allowed the Katy to acquire the SS&S, but only after it extended its line from San Marcos to San Antonio. This was accomplished in 1901, and the Katy proceeded to acquire the SS&S, regaining the original EL&RR route it had owned twenty years earlier. The Katy began service to Shreveport using trackage rights from Waskom. |

|

On August 26, 1905, the Railroad Commission of

Texas (RCT) authorized Tower 61 to begin operating at the crossing

of the Katy and the T&P lines on the northwest side of Jefferson. It housed a

19-function mechanical interlocking plant installed by the Katy, and RCT documentation

confirms that it was staffed by the Katy. The

tower structure appears to be the same design as another Katy tower,

Tower 58, which had opened in Alvarado nine months

earlier. Both towers were built with lengthy, vertical wood panels, the short

walls have three upper floor windows, and one of the short walls has

a centered, lower floor window. The roof shows a wide overhang which mostly

eliminated direct sunlight through the windows (and thus made the interior

cooler and the operators' visibility better.) Photographs of Tower 58 reveal an external

staircase and upper story door on the opposite short wall, but that design

cannot be confirmed for Tower 61 from the available evidence. The 1923 Sanborn Fire Insurance map of Jefferson does

not show a staircase on Tower 61, suggesting either an error by the

cartographer, or that the stairs were inside the building.

In 1923, the

Katy's reorganization out of bankruptcy resulted in the former SS&S route from

McKinney through Jefferson to Waskom being sold to a newly chartered,

Texas-based subsidiary of the Louisiana Railway & Navigation Co. (LR&N) called

the Louisiana, Arkansas & Texas (LA&T) Railway. RCT annual reports began listing

"LR&N" instead of "MK&T" as the railroad crossed by the T&P at Tower 61. The

LR&N also became the staffing organization for tower operations. In 1929, the

Louisiana and Arkansas (L&A) Railroad acquired the LA&T. The L&A's controlling

stockholders began acquiring stock in the Kansas City Southern (KCS) Railroad,

and by 1939, owned a controlling interest. They merged the KCS and the L&A, with

the KCS being the surviving corporation, but its new president and majority

stockholders came from the L&A. KCS eventually built a cutoff near Karnack,

Texas to create a more direct route into Shreveport. The remainder of the line to

Waskom was abandoned. KCS continues to operate the line through Jefferson today.

In 1976, the T&P was merged into MP, which had owned a controlling stock

interest in the T&P since 1930. MP was subsequently acquired by Union Pacific (UP)

in 1982. As a

junction of KCS and UP main lines, the Tower 61 crossing continues to see

significant rail traffic on both tracks.

|

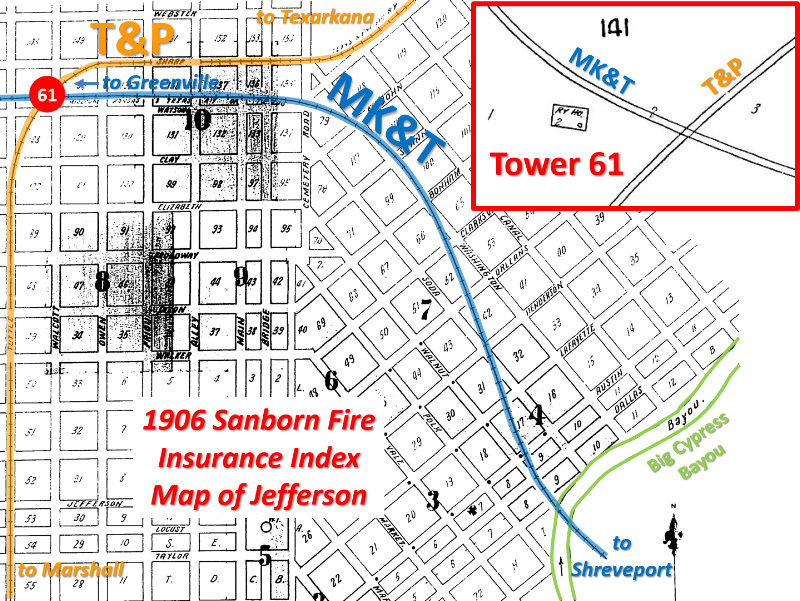

Left: This 1906 Sanborn

Fire Insurance index map shows the T&P entering Jefferson on the

southwest side of town and continuing due north before making a sweeping

curve to the east. The Katy line enters on the northwest side of town,

crosses the T&P at Tower 61 and runs parallel for several blocks before

turning to the southeast. Although Tower 61 existed in 1906, that map

set does not include a detailed map near the crossing. The inset

magnification of the vicinity of Tower 61 is from the 1923 map showing a two-story

"Ry Ho." (railway house.) The circle in the lower right corner of the

building indicates a doorway located on the east end of the south wall,

presumably to enter the lower floor. The photo at top of page shows neither a door nor

staircase, but the south and west walls are not visible. Note that the inset shows the curvature of the Katy tracks

past the tower which matches the view in the photo. The index map, which

shows the Katy as a straight line by the tower, was simply in error. Below: This 2021 Google Earth satellite view of the crossing shows that more than a century later, the Tower 61 diamond is now below the U.S. 59 overpass.  |

Above Left:

Google Street View looks northeast on the UP tracks towards the KCS crossing.

The automated interlocker cabin still sits beneath

US59, adjacent to the crossing. Above

Left: This Google Earth Street View is from the US 59 overpass above the

Tower 61 diamond looking west down the KCS tracks.

Tower 61 was located between the KCS tracks and the equipment cabinet visible at

left.

A third railroad began operating near Jefferson in

1891. It was a tram line to bring logs from nearby pine forests to the Clark & Boice

Lumber Co. mill on Big Cypress Bayou, an enterprise founded by David Boice and

A. D. Clark. The mill site was informally known as North Jefferson, about a mile

northeast of Jefferson's business district. The facility had been built in 1881 directly on the bayou so that

inbound logs could be floated to the mill. In 1891, the mill was upgraded and

rebuilt on the same land, but moved a short distance inland from the bayou as

the lumber company would no longer be floating logs to the mill. Instead, the tram line became the

sole method of moving inbound logs. The T&P tracks ran a quarter mile north of the

mill and became a regular outlet for shipping loads

of finished lumber. The interchange of outbound products with the T&P was done

indirectly since the tram was narrow gauge.

The lumber company's officers

-- A. B. Clark, his son F. I. Clark, and the Secretary C. E. Bancker -- recognized that

they could produce additional revenue by incorporating their tram line

as a separate, common carrier transportation company. The railroad and

the lumber company would be legally separate but owned and operated by the same

management. This would allow

the owners to share in the total revenue the T&P received for carrying outbound lumber

products, a practice known as divisions and allowances. In 1899, the Jefferson & Northwestern (J&NW) Railway was chartered for

this purpose, and it was granted common carrier status by RCT. The salaries of the three officers were split in half to be paid by each company.

In A History of the Texas Railroads

(St. Clair Publishing, 1941), the dean of Texas railroad historians S. G. Reed

described the J&NW as "twenty

miles of narrow gauge road leading to nowhere". That characterization is

unsurprising; remote forests from which logs were hauled back to the mill

certainly qualified as nowhere, and that was still

the primary focus of the railroad. Incorporating as a common carrier

converted the tram line into a classic tap line railroad, legally able

to share in the T&P's revenue on any freight transferred by the

J&NW, even wood products that only had to be moved a quarter mile to

the interchange point.

| The Tap Line Cases |

| A tap line was simply a chartered and

incorporated common carrier railroad owned by a lumber company (or its

closely related interests, e.g. management / investors) that moved logs inbound to

the mill and wood products outbound to interchanges with trunk line

railroads, while also serving the population along its routes. Tap lines evolved

west of the Mississippi River (but also in the State of Mississippi)

where the larger and less populated forests made tap lines essential for

basic transportation to remote outposts. In most cases, tap lines

started as tram lines that were converted for the purpose of realizing two major benefits -- they

would no longer be restricted to hauling logs and company supplies;

and they would share in the trunk lines' revenue for all shipments, inbound

and outbound, even if the tap line carry was only a short distance. Tap lines with access to more than one trunk line

could negotiate

higher division rates by favoring the allowances paid by the

higher-paying connection. This was, in essence, an authorized "kickback". Common carriers also

had two significant legal obligations. They had to offer

transportation services to the public without discrimination, and they had to

set public tariffs and charge fares for their services. Logging trams had always hauled logs for free; a tram was just another component of a mill's operations. Tap lines were common carriers; if a tap line was undercharging (or not charging) their mill to move inbound logs, then other nearby mills wanted the same service at the same price, and therein lay the origin of a major dispute heard by the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC). The investigation began in 1909 covering more than one hundred tap lines in Texas, Arkansas, Louisiana and Mississippi. The ICC rulings issued in April and May, 1912 analyzed each tap line and found that thirty of them, including the J&NW, did not qualify as common carriers. The ICC ruling forbid trunk lines from paying allowances to these tap lines. The ICC ruling was appealed to the U. S. Commerce Court, a Federal Court overseeing the ICC. [The Commerce Court was short-lived, created by the Mann-Elkins Act of June, 1910 and abolished by public law in December, 1913.] The Commerce Court ruled that the ICC had committed a legal error in concluding that regardless of evidence to the contrary, tap lines were not common carriers if they had been converted from private logging trams and were still owned by their mills (or management thereof.) The Court pointed out that the Commodities Clause of the Hepburn Act of 1906 had specifically exempted "...timber and the manufactured products thereof..." from the law's general prohibition on railroads transporting commodities in which they had a financial interest (a prohibition aimed at combatting discrimination and monopoly among major east coast railroads transporting coal from mines they owned.) The Commerce Court's ruling was appealed to the U. S. Supreme Court which issued an opinion in May, 1914 fully affirming the Commerce Court's ruling. In July, 1914, the ICC responded by setting maximum division rates based on mileage and ordering trunk lines to resume paying allowances to the thirty identified tap lines. The ICC's rate-setting authority was immediately challenged in court by the New Orleans, Texas & Mexico (NOT&M) Railroad which complained that tap lines with multiple trunk line connections would prefer the most distant trunk line -- greater mileage meant higher allowances -- rather than the "best" connection. The NOT&M viewed this as unlawful discrimination because they were not allowed to negotiate a higher division rate with tap lines that were "too close". The case eventually reached the Supreme Court which ruled against the NOT&M in 1916, leaving it to Congress to address the issue. As Ernest M. Teagarden described it in The History of Federal Regulation of Railroad Joint Rate Divisions (Bowling Green State University, Ohio, June, 1955) "In the final analysis, about all the Commission had accomplished toward a solution of the tap line problem was to have its power defined by the Supreme Court. Commission policy had been shifted from a policy of preventing proprietary divisions to one of regulating them." The ICC continued to scrutinize railroad practices, but tap line complaints mostly disappeared when nationalization of the railroads occurred during World War I. After the war, the ICC gained a much more important role in railroad management with the Transportation Act of 1920. Individual enforcement actions occurred, but the collective tap line issues faded away. |

|

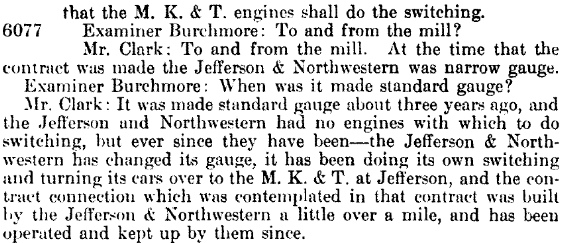

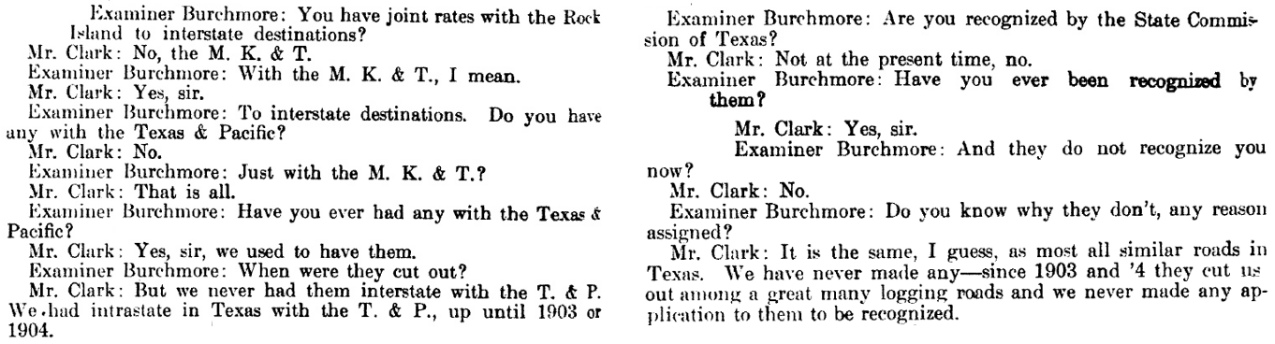

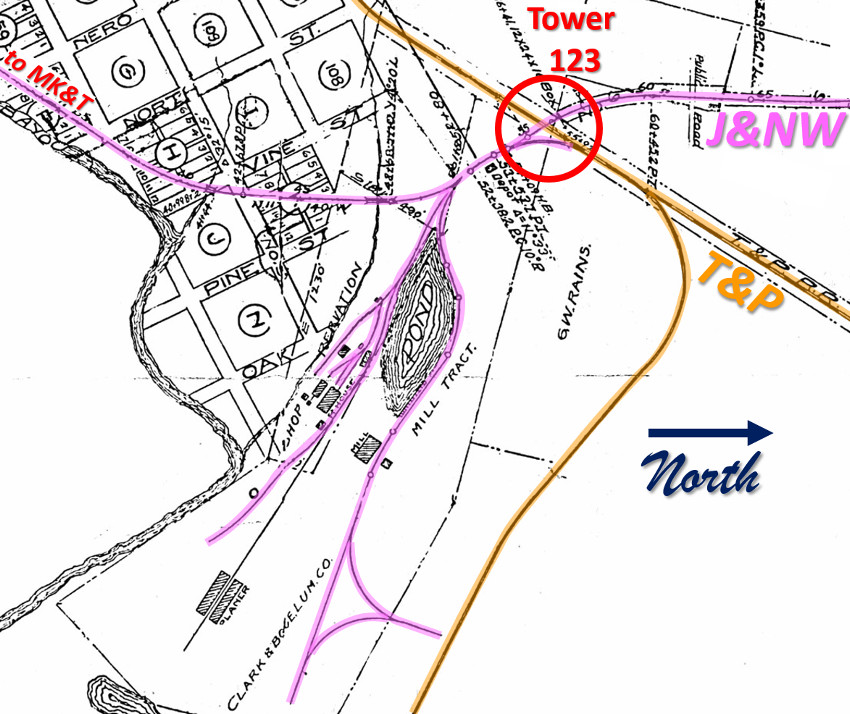

Right: The J&NW's 1906 spur into Jefferson has

been added to this 1901 Sanborn Fire Insurance index map. The future site of Tower 123

is where the "forest tram" portion of the J&NW crossed the T&P main

line. Note that many of the streets on this plat of Jefferson never

existed, especially in the vicinity of the mill. South of the mill, the

T&P spur (at far right) served the Jefferson Iron Co. Below: On January 27, 1911, F. I. Clark, Vice President of the J&NW, was called before the ICC at a hearing in St. Louis to give testimony about the operations of the J&NW (read Clark's entire testimony here.) The ICC was gathering evidence in the Tap Line investigation and the J&NW's examination was one of several conducted on that day. Clark was answering questions from ICC Examiner Burchmore and had begun to explain that the J&NW's 1906 contract with the MK&T stated...  "Transcript of Stenographer's Notes of Hearings Held at St. Louis, Missouri, January, 1911, in Proceeding Before Interstate Commerce Commission" (Harvard Law Library, a Gift of Oliver Wendell Holmes made on January 20, 1923) |

|

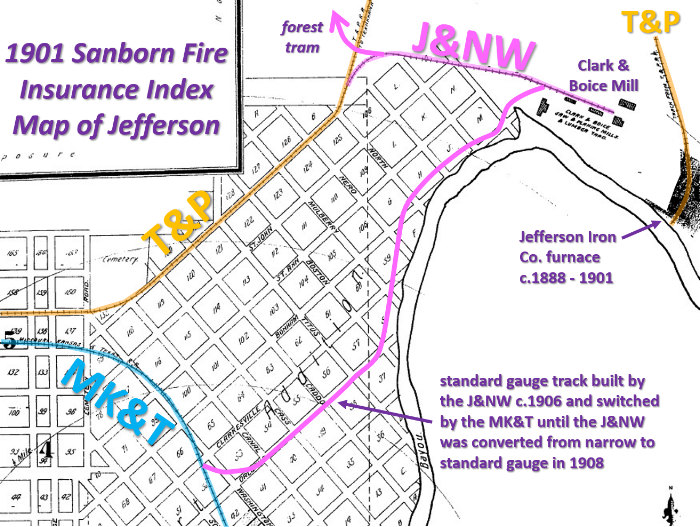

Clark's phrase "contemplated in that contract"

suggests that the J&NW's agreement to build a standard gauge connection to the

Katy in Jefferson was among the terms and conditions of the 1906 contract. It is unlikely they would

have built the spur without the contract also requiring the Katy to switch it since the J&NW was

narrow gauge at the time (and thus, the Katy was also supplying the

railcars.) The J&NW had apparently planned to convert to standard gauge and

they wanted to build and own the track into town so they could eventually serve other

businesses along the spur.

Around 1903, RCT began to revoke common carrier

status for many of the tap line railroads -- including the J&NW -- which it

believed did not meet the qualifications. The J&NW ceased receiving

intrastate

allowances from the T&P around 1903 or 1904, but began negotiating

with the Katy for interstate divisions which were

outside of the jurisdiction of RCT, leading to the 1906 contract.

"Transcript of Stenographer's Notes of Hearings Held at St. Louis,

Missouri, January, 1911, in Proceeding Before Interstate Commerce

Commission" (Harvard Law Library, January 20, 1923)

As the timber was cut out, trams were periodically extended farther into the forest. No longer a private tram, the J&NW still followed this script by extending northward into areas in which Clark and Boice held timber leases. The rails were widened to standard gauge in 1908 and a branch was built to Linden, where a major celebration was conducted for the first J&NW train on November 1, 1911. This created a new revenue opportunity -- movement of freight or people to or from Linden (seat of Cass County) that could be connected to the Katy or T&P at Jefferson. At some point, the Katy spur was modified to connect directly to the J&NW depot near the T&P crossing, and it seems likely that this new track was built in conjunction with the opening of the line to Linden. Otherwise, Linden freight involving the Katy would require the railcars to go into the mill to be redirected to or from the Katy connection via the original spur. To be able to receive intrastate allowances (and surely motivated by the ICC hearings in early 1911), the J&NW re-applied to RCT for common carrier status on November 27, 1911, about four weeks after the first J&NW train pulled into Linden. RCT granted the application in RCT Circular No. 4044 issued on April 10, 1912.

|

Left: (Railway & Engineering Review, May 23, 1925) In the spring of 1925, the T&P ordered a four-lever mechanical interlocking plant to be installed at the J&NW crossing at Jefferson. On October 13, 1925, Tower 123 was commissioned by RCT as an 8-function mechanical cabin interlocker. A file in the RCT archives at DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University states that the interlocker was "4,770 ft. north of T&P passenger station at Jefferson". The interlocker was inspected by RCT on February 1, 1926 and was described as "normal clear for T&P" and "operated entirely by train service or other employee of J&NW". The crossing had existed since the initial tram line construction c.1891 and had been uncontrolled since then, although a gate may have been installed. In the January 2, 1943 edition of Railway Age, Tower 123 appears in a table labeled "Manual control using miniature levers or push buttons with no mechanical locking but with circuit interlocking" for 1942. This might have been a conversion to pushbutton controls in a locked compartment on a post mounted outside the cabin so that the cabin was no longer necessary. This approach became the predominant control arrangement for cabin interlockers in Texas, and is still in use at Tower 103. |

|

Left:

This west-facing 1918 ICC Valuation Map of the J&NW highlights the rail

lines near Tower 123, which was still to be implemented seven years in

the future. The J&NW spur had been rebuilt to go directly to the depot

near Tower 123 and merge into the line to Linden. The spur track

directly to the mill was no longer in place (hat tip, Texas

Transportation Archive) Below: This 1958 image ((c)historicaerials.com) shows the J&NW right-of-way sixteen years after the tracks were abandoned. The Tower 123 crossing was located at 32 46 22N, 94 20 23W, but satellite imagery shows no evidence of it today. The location of the cabin relative to the diamond is unknown.  |

|

Left: The J&NW's construction north out of Jefferson had gone through Lanier,

bypassing Linden, the seat of Cass

County. A five-mile branch line was proposed, and the J&NW

began the survey work for it in the spring of 1911. (Jefferson

Jimplecute, April 28, 1911, quoting the

Cass County Sun, the newspaper of

Linden) Right: The J&NW branch to Linden was completed in late October, 1911, and a "first train" picnic celebration was held at Linden on November 1, 1911. (Jefferson Jimplecute, October 27, 1911) |

|

|

|

Right: About 1900, the Clark & Boice Lumber

Co. acquired the Kildare Lumber Co. and its common carrier tram, the

Kildare & Linden Railroad. The Kildare Lumber Co. had taken over the

Jefferson Lumber Co. in 1892, including its tram, the Atlanta & Mt.

Pleasant Railroad. Both trams ceased operating as common carriers, but

they continued to haul logs to their respective mills at Kildare and Bancker. RCT records list 1912 as the year the J&NW built 31 miles of track from Jefferson to Camp, but that was merely an initial "catch up" report. In F. I. Clark's testimony before the ICC in January, 1911, he stated that the J&NW had "...32 miles of main line and about 3 miles of spur track." The main track to Camp accounts for 31 miles. The 5-mile branch to Linden opened in November, 1911. Also, the Texas Forestry Museum Tram Database notes that an article in American Lumberman in 1906 stated that the J&NW had 25 miles of track. That would place the end of the line at Carterville. For construction through 1906, the Texas Transportation Archive lists J&NW track mileage increments of 12 (1901), 6.5 (1902), 4 (1903), -4.5 (1904) and 7 (1906.) In his testimony to the ICC, Clark explained to Examiner Burchmore that it would take "four or five years" to finish cutting the currently accessible timber, after which the mill at Jefferson would be closed. Burchmore: "What about the railroads?" Clark: "The railroads will continue to operate. I will say that we are constructing and building road right along. We are now -- the end of the road is now within about twelve miles of the Cotton Belt. We are down in that neighborhood and we are working as fast as we can today to get that line up." Burchmore: "Do you run through any more timber?" Clark: "No, there is no more timber." Burchmore: "What is the purpose of making that connection?" Clark: "Simply to have a railroad." Burchmore: "Might it be suggested that you are building across to the Cotton Belt in order to sell the line you have now, to save it?" Clark: "That is our idea exactly. We have considered it a valuable property and expect to get more than it has cost us out of it in some way, either by the sale of the property or by the operation of the road." The Cotton Belt connection was at Naples but the J&NW would not reach it until 1926, with an intermediate termination at Marietta in 1917. |

|

The connection to the St. Louis Southwestern ("Cotton Belt") Railroad at Naples did not save the J&NW. It struggled financially and it ultimately decided to abandon 29 miles of track from Givens (Linden Junction) to Naples in 1933. It was then sold in foreclosure in 1934 to a newly organized "Jefferson and Northwestern Railroad" (replacing Railway.) The new J&NW continued to battle financial problems for another eight years. In 1942, all remaining tracks of the J&NW were abandoned.

Above: This 2021 Google Earth

image has been annotated to show the narrow gauge tracks (pink arrows) of the

Historic

Jefferson Railway, a tourist train that runs from downtown Jefferson to

the Boice and Clark mill site and back. Some of the trackage is on the original

right-of-way of the J&NW spur. The blue circle is the best guess for the site of

the J&NW switch for the revised spur (blue arrow) that led directly to the depot

and Tower 123. The train completes its run by circling a loop near the mill site

and rejoining the main line (orange arrow) for the return trip to town. The mill

site is now a private park for camping and recreational vehicles.

Below: The private railcar

Atalanta once owned by Jay Gould is on display in Jefferson.