Texas Railroad History - Tower 133 - Lancaster

A Crossing of the Missouri - Kansas - Texas Railroad and

the Houston & Texas Central Railway

The town of Lancaster in southern Dallas County was founded in the 1850s and had a Post Office by 1860. In

1872, it appeared to be

geographically positioned to become a stop on the first railroad into Dallas County,

the Houston & Texas Central (H&TC) Railway, which was building north toward the

Red River. Instead, the rail line passed four miles east through

the tiny community of Prairie Valley (later renamed Wilmer.)

Denison was reached the following year and there, the H&TC connected with the Missouri -

Kansas - Texas (MKT, "Katy") Railroad which had built south through Indian

Territory and bridged the Red River. As traffic began to flow along the H&TC's

line, it was Prairie Valley and, four miles farther north, the new town of Hutchins (named for an early

H&TC investor) that saw trains in southern Dallas

County, not the more established town of Lancaster.

The arrival and

immediate success of "the Central", as the H&TC was known, motivated nearby

towns to begin seeking rail connections to it. On December 27, 1875,

citizens of Lancaster held an organizational meeting to discuss getting access

to the H&TC with a "tap

line", a term frequently used in that era to describe a

rail line

from a town without a railroad to the nearest main line that could be "tapped"

for service. The consensus was that a Lancaster Tap Railroad should be

built to connect Lancaster with the H&TC at either Prairie Valley, only four

miles east, or Hutchins, about five miles northeast. The meeting was reported to the

Dallas Daily Herald in a

Letter to the Editor dated January 15, 1876. The author of the letter self-identified as "J. H. S.", presumably Dr. James H. Swindells who is mentioned in

the letter as the appointed Secretary of the Lancaster committee.

|

Left:

Letter to the Editor, the Dallas Daily Herald, January 21, 1876

edition. The letter

states the committee's conclusion

that the cost of obtaining all of the necessary right-of-way to Hutchins would be unreasonable, in

addition to

the expense for an extra mile of construction. Instead, building a 3.8 mile

line due east using "wooden rails covered with strap iron ... bolted to the wood"

would be feasible for $12,500 and could be accomplished very quickly. The

line could be operated "for two or three years as a tramway." The

tramway never materialized, but the citizens of Lancaster were not

deterred. An article in the Dallas Weekly Herald

of August 13, 1885 (below)

described a recent "session" to discuss the Lancaster Tap. The article

mentions that Lancaster "fully guaranteed" the railroad's up

front demand for $5,000, plus land for a depot and right-of-way in

town. Unfortunately for Lancaster, the H&TC's bankruptcy in 1885 delayed the project for a few years.

Above: Lancaster is

one corner of a triangle of railroad towns in southern Dallas County

along with Wilmer and Hutchins. The construction of the Dallas &

Waco Railway (at the behest of the Katy) through Lancaster in 1888 might

have alleviated Lancaster's need for the "Tap", but it was nonetheless

built in 1889-1890. |

Despite the earnest intentions of the citizens of

Lancaster, neither the tramway to Wilmer nor the tap line to Hutchins

materialized out of the initial meeting in 1875. It was more than a

decade later in 1888 that Lancaster finally obtained rail service, but it was not the

Lancaster Tap. The Dallas & Waco (D&W) Railway built south out of

Dallas,

passing through Lancaster and Waxahachie on its way to reaching

Hillsboro in

1891. The D&W had been sponsored by the Katy and was formally merged into the

Katy in 1891. The line became substantially more valuable in 1907

when the Katy sold trackage rights between Waxahachie and Dallas to the Trinity

& Brazos Valley (T&BV) Railway. This helped to complete the T&BV's line between

Houston and Dallas, a route that remains in active use today by Burlington

Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) Railway.

If the arrival of the Katy in Lancaster

spurred a renewed interest in the idea of the Lancaster Tap, that interest appears to

have been primarily on the part of the H&TC. Perhaps

the H&TC simply wanted to compete with the Katy for traffic at Lancaster. While the

details of the planning and financing have not been uncovered,

it's clear that in late 1890, a railroad named the Lancaster Tap began operating the five miles

between Lancaster and the H&TC main line at Hutchins. The leading authority on

Texas railroad history, S. G. Reed, has little to say about the origins of

the Lancaster Tap Railroad in his authoritative book A

History of the Texas Railroads (St. Clair Publishing Co., 1941.)

During

the years 1889 and 1890 funds had been advanced by the H. & T. C. for the

building of a line 4.75 miles in length from Hutchins, ten miles south of Dallas

to Lancaster which was called the Lancaster Tap. No charter was

ever taken out for this road. It was purchased by the H. & T. C., on September

30, 1905, for the sum of $50,000 payable in ten years.

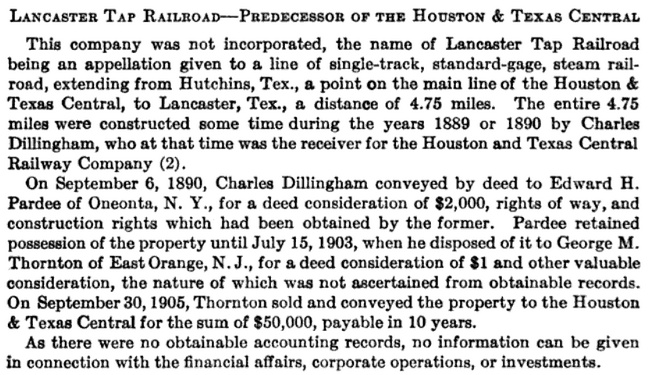

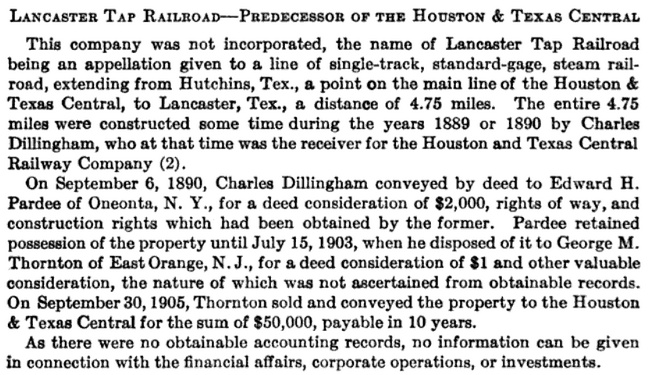

The Lancaster Tap appears in Valuation Reports, Vol. 36 published

by the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) in 1932.

The H&TC was forced into receivership in 1885, even

though it had come under the control of Southern Pacific (SP) two years earlier. Three Receivers were named by the bankruptcy court,

but two of them departed the case at the outset and only Charles Dillingham

remained. From the ICC description, it appears that Dillingham (either on his

own assessment or more likely on recommendation of

railroad management) acquired rights-of-way and construction rights between

Lancaster and Hutchins. This would correspond to Reed's

declaration that "funds had been advanced by the H&TC"

(which also implies that Dillingham was acting in an official capacity as H&TC

Receiver, not on his own as a private investor.) Edward Pardee then paid $2,000 for

these assets on September 6, 1890. Pardee owned the line for

more than a decade before he sold it to George Thornton in 1903 for "$1 and other valuable consideration". In 1905, Thornton sold the

property to the H&TC for "$50,000, payable in ten years."

While details are lacking, the financial arrangements certainly appear unusual. From

the ICC description, and confirmed by newspaper articles at the time, it is clear that when Pardee acquired the

deed and other assets from Dillingham for

$2,000 in September, 1890, construction of the Lancaster Tap had already

been completed. But how did a railroad in bankruptcy acquire the capital to build five

miles of railroad, and why would it then sell the whole thing for $2,000? Most likely (but nonetheless speculation), Pardee (or

perhaps a syndicate

led by him) had provided the cash flow to build the line, and there's evidence that he did so by

using H&TC's

construction forces (essentially hiring the H&TC to build itself!) The transaction with Dillingham was simply the final step,

i.e. Dillingham acquired and held the track easements and construction rights as

security for the line's completion. When the job was finished, Dillingham sold

them to Pardee, almost certainly in exchange for

a period of exclusive rights to operate Pardee's new Lancaster Tap as part of

the H&TC. This would have been a favorable arrangement for Dillingham since,

in receivership, internal funding for capital projects of this nature would have

required approval of the bankruptcy judge. Instead, the H&TC would incur minimal cash

outlay (for construction rights and track easements) for the Lancaster Tap project; funding for labor and materials was

(presumably) provided by Pardee. The low final price paid by Pardee would then

reflect the substantial construction

expense he had already incurred, most likely under a prior agreement with

Dillingham. As owner, Pardee may or may not have received dividends

from the H&TC related to the line's operation, but he certainly expected to sell

the Lancaster Tap to the H&TC in the future at a tidy profit.

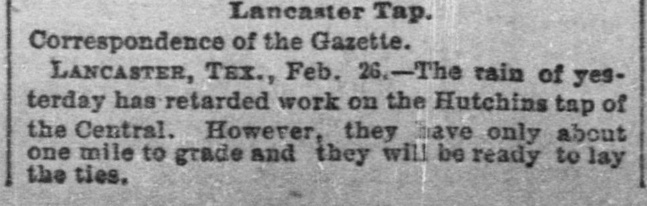

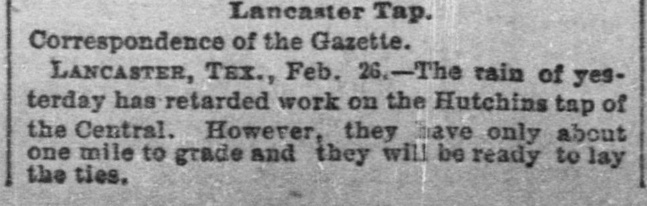

Above Left: The

Fort Worth Weekly Gazette of February 28,

1890 mentions that only a mile of grading remains to be accomplished before tie

laying can commence. Given typical wet winter weather in north Texas,

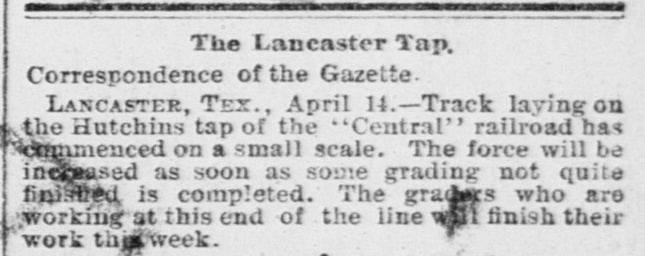

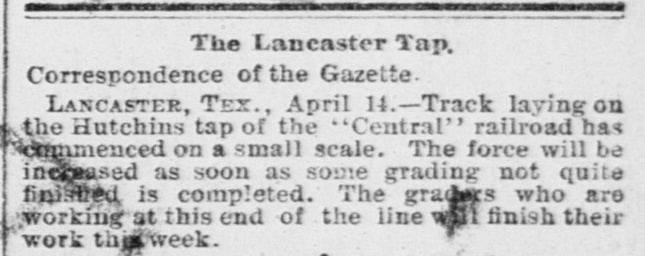

construction must have begun in 1889. Above Right:

The Fort Worth Weekly Gazette of April

17, 1890 states that track laying has begun (implied to be at Hutchins) while

the final grading "at this end of the line" (Lancaster) is expected to be

concluded within the week. Since the grading was "not quite finished" yet there

was only a mile to complete as of late February, the month of March likely saw

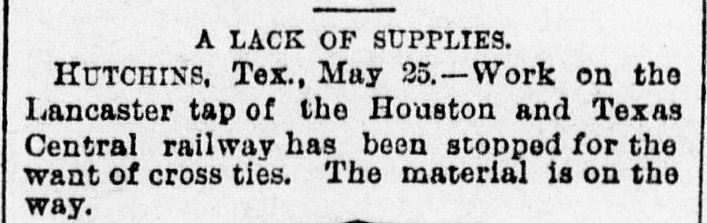

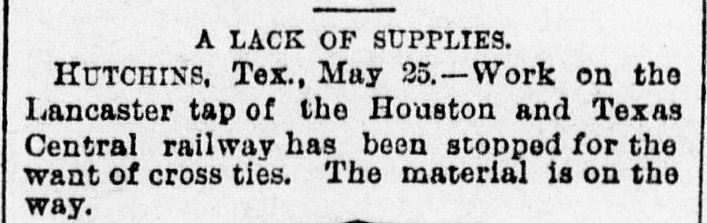

considerable precipitation, delaying progress. Below Left:

The Galveston Daily News of May 26,

1890 reports that a shortage of crossties has temporarily stopped construction

on the Lancaster Tap. Below Right:

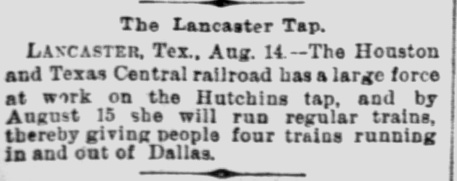

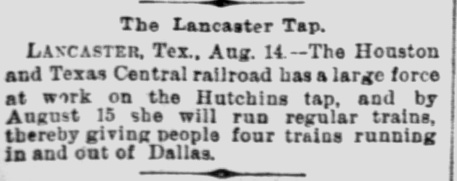

An article in the Galveston Daily News

of August 15, 1890 (but datelined the day before) anticipates that "regular

trains" (i.e. not "construction trains") will begin to serve Lancaster from Hutchins the following day. Perhaps

significantly, the article attributes the "large" construction force directly to

the H&TC.

The theory that Pardee funded the construction while

Dillingham held title to the right-of-way easements and other assets is

compatible with the fact that the Lancaster Tap was never chartered. The H&TC

was in receivership, certainly in no position to pursue a charter from the Legislature,

especially for a line it would not own when completed. Pardee, either out of

ignorance or daring, did not seek a charter, knowing the entire enterprise was

ultimately to be operated as part of the H&TC. Thus, despite the fact that the

Lancaster Tap had no legal right to exist under Texas law, it was providing a

valuable service to Lancaster. The State of Texas had

little impetus to file a lawsuit to shut it down and they did not do so. Had

they filed suit, it

would have been to vindicate state law, but the state was already litigating a

suit under that law claiming that SP's ownership of the Austin & Northwestern

(A&NW) Railroad had never been authorized by the Legislature. A favorable ruling

in that court would suffice to establish the validity of Texas law requiring

charters from the Legislature to authorize routes and consolidations. There was

no need to take action against the Lancaster Tap.

Newspaper articles for

the next decade show the H&TC paying taxes for the Lancaster Tap while operating

it

and incorporating it into reports submitted to the Railroad Commission of Texas

(RCT). The H&TC nonetheless recognized the need for a charter amendment from the Legislature

to allow it to merge the Lancaster Tap and several other railroads. Early in the

new legislative session that convened in January, 1899, a bill amending the

H&TC's charter was passed to allow it to acquire the Lancaster Tap and the other

railroads. Texas Governor Joseph Sayers vetoed the legislation, citing

interference with the on-going court case against SP's ownership of the A&NW. The bill would, in fact,

have ended that lawsuit by legalizing SP's ownership of the A&NW through the H&TC.

Two years later, the H&TC continued to press its case in the Legislature for

approval to acquire the Lancaster Tap and other railroads. The law was

finally enacted and took affect on July 7, 1901.

|

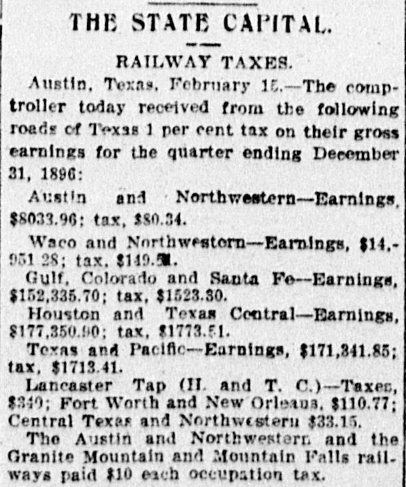

Left Top:

The Galveston Daily News of

Nov. 28, 1895 reported H&TC's quarterly passenger revenue taxes, of

which the Lancaster Tap was listed first among the several railroads the

H&TC was operating.

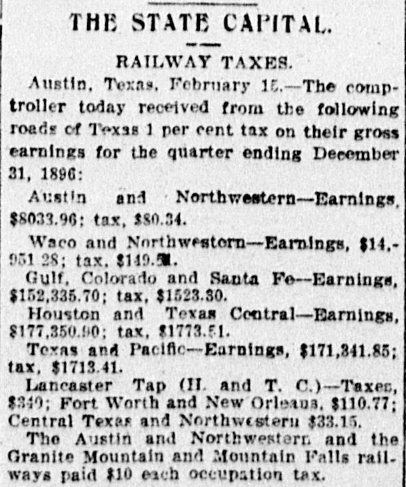

Right: The

Houston Daily Post of February 16, 1897 had an article on

"Railway Taxes" which included the Lancaster Tap and other H&TC

operating accounts.

Left Bottom: This paragraph is from an article in

the Galveston Tribune of March

16, 1899 discussing various activities in progress at

the current legislative session in Austin, including the governor's

recent veto of the bill authorizing the H&TC to acquire ownership of

several railroads. |

|

|

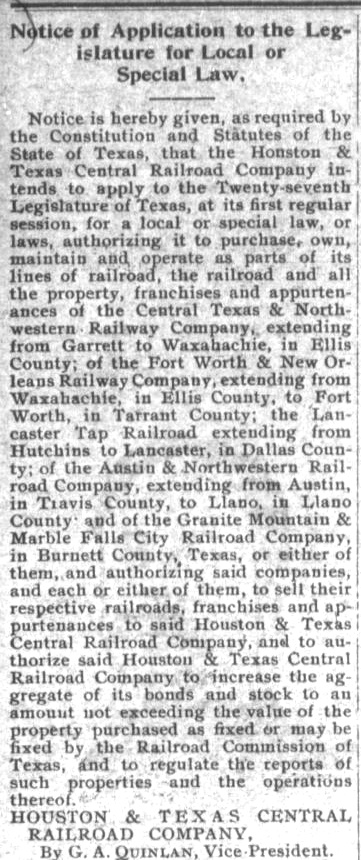

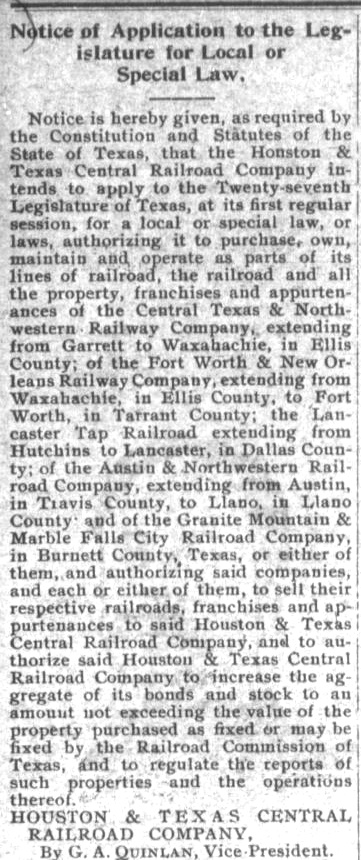

Left:

The La Grange Journal of

January 3, 1901 carried this official announcement by the H&TC that it

was applying to the newly convened 27th Texas Legislature for a "local or

special law" to authorize it to formally acquire several railroads.

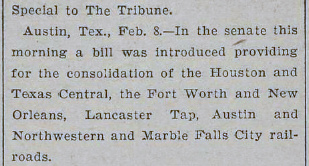

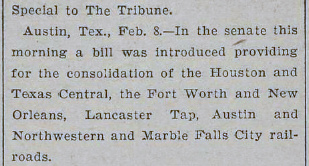

Right Top: The

Galveston Tribune of February 8, 1901 mentioned that a bill had been

introduced in the Texas Senate to allow the H&TC to proceed with its

proposed acquisitions.

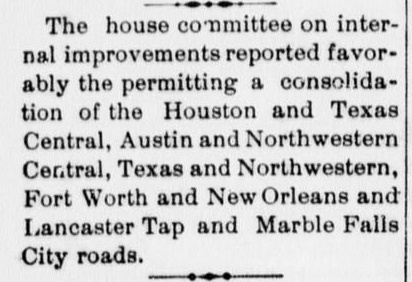

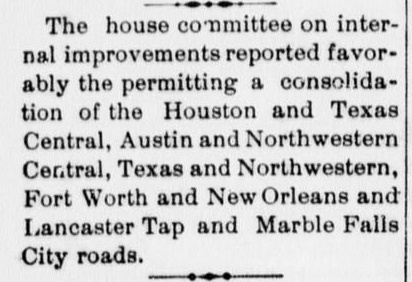

Right Middle: The

Bastrop Advertiser of March 2, 1901

reported that a committee of the Texas House had voted to send the H&TC

consolidation bill to the House floor.

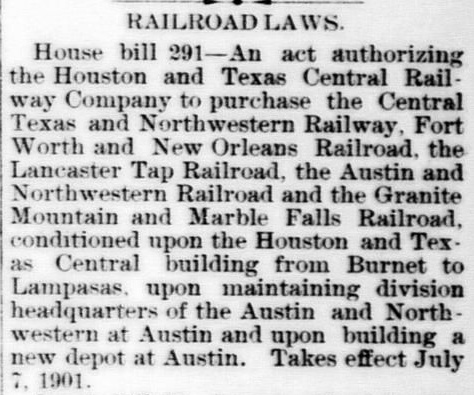

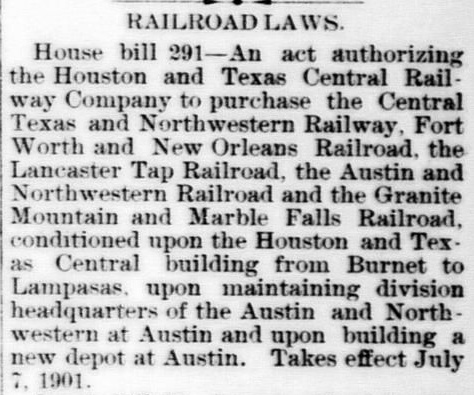

Right Bottom:

The McKinney Democrat

newspaper carried announcements of newly enacted railroad laws. This

one, in the May 2, 1901 issue, covered the law granting the H&TC's request to acquire

several railroads. The summary does not state whether the governor

signed the bill into law. It's possible the governor vetoed the bill and

the veto was

overridden by the Legislature. Gov. Sayers had vetoed essentially the same bill

two years earlier. He remained in office by being reelected in

November, 1900. |

|

By the summer of 1901, the H&TC had the necessary legal

authorization to purchase and consolidate the railroads it was operating, but

its acquisition of the Lancaster Tap did not occur until four years later,

September 30, 1905. Meanwhile, Edward Pardee sold the Tap to George Thornton on

July 15, 1903. The ICC was unable to uncover details of the "valuable

consideration" that Pardee received in making the sale to Thornton for $1.

Building southwest from Hutchins, the H&TC tracks at Lancaster crossed the

Katy roughly a quarter mile north of the H&TC depot, which was located only

a hundred feet or so west of the Katy tracks. Whether the depot was built on the land

promised by the Lancaster committee in 1885 is unknown but seems likely since

the H&TC could have acquired land for a depot east of the Katy and avoided

the need for a

crossing altogether. Whatever the case, the diamond was installed and the crossing was

uncontrolled for nearly thirty years. This meant that all trains on both lines had to come to

a complete stop before proceeding to cross.

The Lancaster Tap was never a

major branch for the H&TC, but the line carried sufficient traffic to pay its operating and

maintenance expenses into the 1920s. By 1923 and probably much earlier, the H&TC

was operating only one mixed train daily (but no trains on Sunday) from Hutchins to Lancaster

and back to Hutchins each morning. A mechanical cabin interlocker with eleven

functions designated Tower

133 was authorized for operation by RCT on February 8, 1928 to guard the

H&TC/Katy crossing at Lancaster. The interlocker

improved efficiency for Katy and T&BV trains; they no longer had to stop at

Lancaster before crossing the H&TC unless the diamond was actually occupied.

A cabin interlocker was typically a small hut (usually adjacent to the tracks

but sometimes in another nearby structure, e.g. a depot) that

housed

the interlocking plant and its controls for the signals that managed access to

the crossing. The signals would normally be set to give a "Proceed" indication

on the busier route, in this case the Katy tracks, so that Katy and T&BV trains

would not need to stop for the crossing. When an H&TC train needed to cross, it

would stop short of the diamond and a member of the train crew would enter the

hut. He would set the controls to give his train the "Proceed" signal while giving a "Stop" indication on the Katy tracks. Once the train had crossed, the crewmember would return the

controls to the normal position, allowing unrestricted movement on the Katy

tracks.

The minimum standard interlocker for a crossing of two railroads

had twelve functions: four home signals, four distant signals and four

derails, one of each in all four directions. The derails physically prevented a

locomotive from approaching the diamond without a "Proceed" signal. The distant signals gave an indication

for approaching trains to know whether they needed to begin slowing to stop short of the crossing.

The signals near the crossing, the home

signals, gave the same indication, used by trains that were stopped waiting for

the "Proceed" signal. The Tower 133 interlocker had only eleven functions; a distant signal was not needed for

northbound movements on the H&TC tracks. As the crossing was close to the

H&TC station and there were no H&TC tracks south of it, northbound H&TC trains

were simply parked there, waiting for the "Proceed" indication on the home

signal.

The precise location

of the crossing and its interlocker cabin has not been determined. RCT records held at DeGolyer

Library, Southern Methodist University, state only that the crossing was midway

between Katy mileposts 781 and 782. An H&TC employee timetable from 1923 lists

the Katy crossing and the H&TC station as having "Distance from Hutchins" of

4.44 and 4.74 miles, respectively, making the crossing 0.3 miles north of the

station. Ironically, the same timetable lists their "Distance from Houston" as

258.76 and 258.96 miles, respectively, making the crossing 0.2 miles north of

the station. None of the Sanborn Fire Insurance maps of Lancaster include

details of the vicinity of the crossing.

|

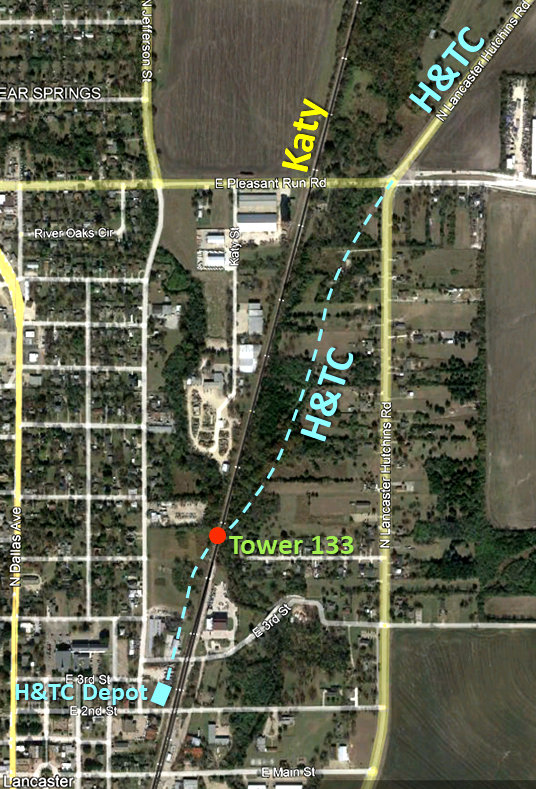

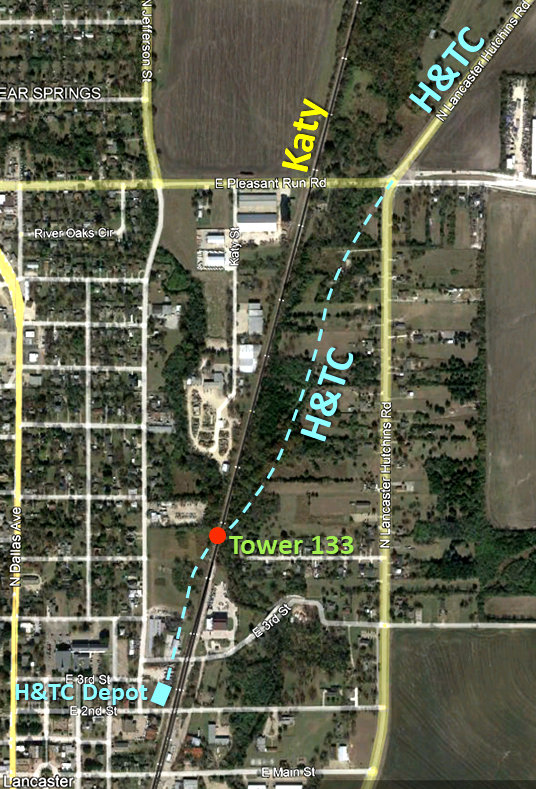

Left:

This Google Earth image is annotated with the best guess for the path of

the H&TC right-of-way and the Tower

133 crossing. South of Hutchins, the H&TC right-of-way sits beneath

Lancaster Hutchins Rd. until it reaches the intersection of Pleasant Run

Rd. The road turns south but the railroad went more or less straight

ahead and then curved to cross the Katy tracks in the vicinity (and

likely north) of where Pierson St. (the unmarked street beneath "Tower

133") would project to cross the Katy tracks. Pierson St. aligns with

5th St. to the west, which appears on a 1928 Sanborn detail map showing

the H&TC and Katy tracks remaining parallel that far north. This

suggests the crossing was north of Pierson St., still within the

boundaries of Katy mileposts 781 and 782 and within 0.2 to 0.3 miles of

the H&TC station. The dashed line is simply a guess as to the route, and it's possible the crossing aligned with the next street

north, 6th St., 0.3 miles from the H&TC station. Wherever it

was, the diamond had a very acute angle.

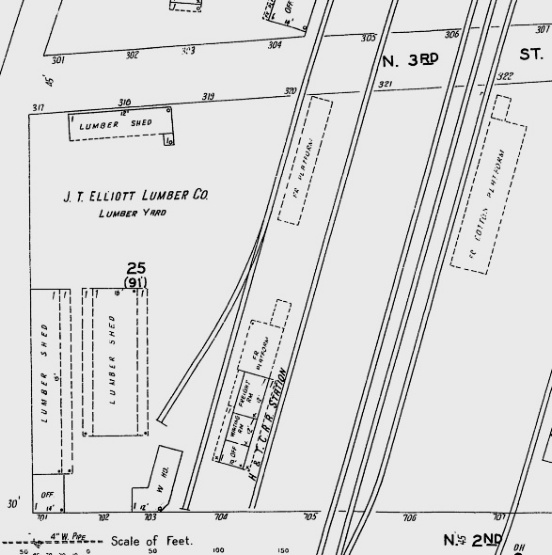

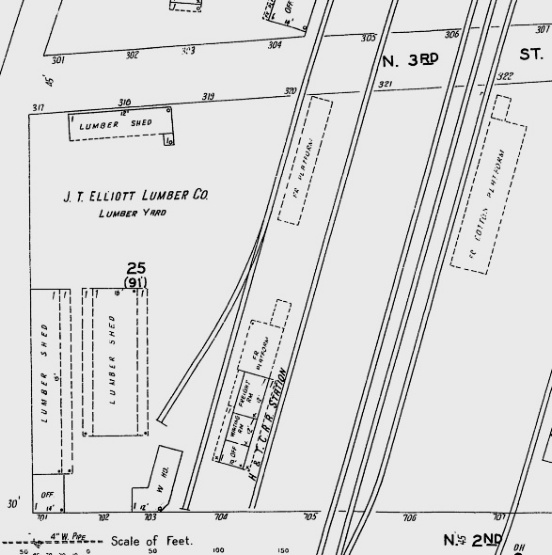

Below: 1928 Sanborn map showing the H&TC station

on N. 2nd St. near its crossing of the Katy triple tracks

|

|

Left:

This photo looks south along the Katy tracks showing the block signal at

milepost 781.3. The

equipment cabinet visible beyond the block signal houses electronics for

the signal and the associated siding switch, and is labeled

"West Lancaster". The cabinet is about where Pierson St. would

intersect the Katy tracks and is 0.2 miles north of the site of the H&TC

depot. The hypothesized location of Tower 133 was a small distance north

of that projected intersection, but not more than 0.1 miles in order to

remain within the 0.3 mile limit from the H&TC depot. Thus, the crossing could have been within this view, or it

could have been as much as 400 ft. behind the camera. (Jim King photo,

2005)

Below:

This is a north-facing view of the cabinet and the block signal from the

grade crossing of N. 3rd. St., milepost 781.45 on the Katy tracks. The

crossing was probably north of the current cabinet site but within 0.1

miles of

it. (Google Street View, October 2019)

|

SP's operating company for its Texas and Louisiana

railroads was the Texas & New Orleans (T&NO) Railroad. SP leased the H&TC to the

T&NO in 1927 and then merged it into the T&NO in 1934. T&NO abandoned the

Lancaster branch that same year and the abandoned right-of-way was used for the

construction of Lancaster Hutchins Road. H&TC's dead-end branch to Lancaster was

simply too short to continue to provide value to T&NO given that the station at Hutchins

was less than five miles away offering a larger assortment of scheduled trains.

Also, the Katy and H&TC tracks at Lancaster were close and parallel, hence

businesses there probably had (or could obtain) better service from the Katy

with its busier line. By this time, Lancaster was also served by an interurban

railroad which reduced the ability of the steam railroads to capture passenger

traffic for short trips to Dallas or Waxahachie.

The

Katy tracks through Lancaster managed to survive to the present simply because they were part

of an important and lengthy north/south rail line. In 1931, a critical event

that affected Lancaster rail traffic was the end of the T&BV's receivership.

This resulted in the creation of the Burlington - Rock Island (B-RI) to own and

operate the T&BV's routes. It was effectively a paper railroad, owned equally by

Burlington Northern (BN) and the Rock Island. B-RI inherited T&BV's trackage

rights on the Katy from Waxahachie through Lancaster to Dallas and was able to

sustain a viable business on this lengthy route to Houston.

After the Rock Island's demise in 1980, the B-RI was merged into BN which continued to operate

substantial traffic between Dallas and Houston.

In 1988, the Katy was merged into Missouri Pacific (MP) which

was already a subsidiary of Union Pacific (UP). In 1990, MP abandoned a ten-mile

stretch of the Katy tracks north of Italy, leaving

a short stretch of main track south of Waxahachie to serve a business. Effectively, Waxahachie

became the

southern terminus of the former Katy line. BN was

providing the bulk of the traffic through Waxahachie on the former B-RI,

connecting to the Katy for the tracks to Dallas. In 1996, BN merged with the Atchison,

Topeka & Santa Fe (AT&SF) Railway to form BNSF. That same year, UP acquired SP

(which also had tracks through Waxahachie on a route from Ft. Worth to the SP main

line near Ennis; these tracks had become SP property by being included in the "special law"

in 1901 that allowed the H&TC's acquisition of the Lancaster Tap.) The UP/SP and BN/AT&SF mergers required legal

agreements to gain Federal approval, and one of the agreed provisions was that

UP would sell the line between Waxahachie and Dallas to BNSF. Hence, BNSF now

owns the former Katy tracks through Lancaster.

Above: This building appears

to be either a relic of the final H&TC depot in Lancaster or more likely, an

adjacent freight house. Either way, it's probably been heavily modified.

Historic aerial imagery shows the building at this

location, very close to (and perhaps "on") the site of the H&TC depot, at least as early as 1956, only 22

years after the Lancaster branch was abandoned. North 2nd St. is barely visible at far right, and the utility pole in

the distance is adjacent to the BNSF (ex-Katy) tracks. Whether the building's

structural heritage dates to the H&TC era, and if so, the extent of the

modifications, is unknown. The building was razed or removed not long after this photo was taken. (Jim King,

2005)

Below: The Katy

depot still stands trackside in Lancaster on the northwest corner of Pecan St.,

but it is located about 400 ft. farther south than it originally was. The

Lancaster Historical Society conducts meetings in the depot and appears to have

some responsibility for managing it. (Google Street View 2021)

Below: Around 1912, the Southern Traction interurban

railway built south from Dallas through Lancaster on its way to Waxahachie and

beyond. In 1916, it merged with other interurban railways in the Dallas area to

create the Texas Electric Railway. The former interurban right-of-way through

Lancaster is now Dallas Ave., and its former Lancaster station remains standing

on the northwest corner of Dallas Ave. and Main St. (Google Street View 2021)