Texas Railroad

History - Tower 175 - Etter

A Crossing of the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railway

and the Panhandle & Santa Fe Railway

Left:

The Tower 175 diamond was sitting in the weeds a few yards from its historic

location when this photo was taken c.2001. The silver painted hinge post

adjacent to the Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) tracks marks the location of

the swing gate that protected the diamond after the interlocker was removed. The

BNSF tracks are part of a route between Amarillo (to the right) and Las Animas,

Colorado (to the left). The crossing tracks were of Rock Island heritage but

came under Texas Northwestern (TXNW) ownership in 1982 when the last seventeen

miles of the line west of the crossing was

abandoned. The diamond and a short segment of track to the west was retained, presumably

to avoid the expense of reinstalling the diamond if nearby land was acquired for

a rail-served industry. The diamond was removed in the late 1990s or early 2000s.

Left:

The Tower 175 diamond was sitting in the weeds a few yards from its historic

location when this photo was taken c.2001. The silver painted hinge post

adjacent to the Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) tracks marks the location of

the swing gate that protected the diamond after the interlocker was removed. The

BNSF tracks are part of a route between Amarillo (to the right) and Las Animas,

Colorado (to the left). The crossing tracks were of Rock Island heritage but

came under Texas Northwestern (TXNW) ownership in 1982 when the last seventeen

miles of the line west of the crossing was

abandoned. The diamond and a short segment of track to the west was retained, presumably

to avoid the expense of reinstalling the diamond if nearby land was acquired for

a rail-served industry. The diamond was removed in the late 1990s or early 2000s.

The TXNW main tracks approach from the east, come under the US 287

overpass (in the distance at left) and continue west another 500 ft. where they split into

southeast and northeast quadrant connectors to reach the BNSF tracks. The TXNW main track

that previously approached the diamond from the east has been removed west of

the connecting track junction. In the photo,

the southeast connector hosts the box cars, and they appear to extend all the way

back to the TXNW main line connection. (Jim King photo)

By 1910, the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific (CRI&P)

Railroad was operating two routes through the Texas Panhandle: the Golden

State Route and the Choctaw Route. Both had been

built primarily for the purpose of making a west coast connection at

Tucumcari, New Mexico, where Southern Pacific (SP) operated a line south to

El

Paso that continued onto their Sunset Route to California. To reach

Tucumcari, the

Golden State Route went from Liberal, Kansas diagonally across the Oklahoma

Panhandle and the northwest corner of the Texas Panhandle, passing through

Stratford and Dalhart,

and entering New Mexico 41 miles southwest of

Dalhart. The Choctaw Route crossed the Texas Panhandle on a due

west heading through Amarillo, providing Oklahoma City

and points east with access to the SP connection at Tucumcari. To comply with

Texas' railroad ownership laws, these lines were officially owned by the

Chicago, Rock Island & Gulf (CRI&G), Rock Island's Texas-based subsidiary.

Rock Island shared the Texas Panhandle

with two other railroads. The Fort Worth and Denver City (FW&DC) had been the

first to lay tracks into this region, building mostly through the western

Panhandle in 1888 to reach the New Mexico border at the

new town of Texline. There, it connected to Colorado & Southern tracks to form a

continuous route between Fort Worth and Denver. The other Panhandle railroad was the

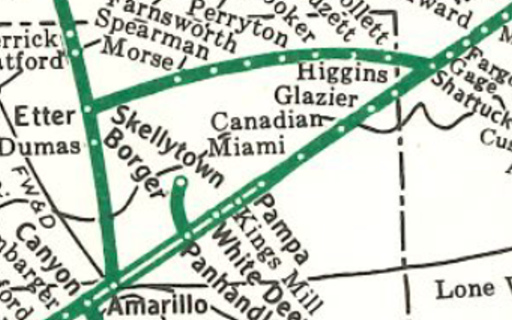

Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe (AT&SF) Railway. By 1902, it was operating a route

from Wichita, Kansas southwest to Clovis, New Mexico via Shattuck, Oklahoma, and

the Texas towns of Canadian,

Pampa, Amarillo, Canyon

and Farwell. Like Rock Island, Santa Fe complied with state law by accomplishing this work

under Texas-based subsidiaries. Its operating subsidiary in the Texas Panhandle

had been known as the Southern Kansas Railway, but it was renamed the Panhandle

& Santa Fe (P&SF) in 1914.

By 1910, Santa Fe had begun a

significant network expansion south of Amarillo, but north of Amarillo, the main line

comprised Santa Fe's only tracks until 1917 when a branch

from Shattuck, Oklahoma was built into the far northeastern corner of the Panhandle.

In Texas, this branch helped to establish several new towns -- Follett, Darrouzett, Booker

-- and Perryton, the new county seat of Ochiltree

County. The branch terminated 26 miles southwest of Perryton at Spearman,

another town platted in 1917 anticipating the arrival of Santa Fe's tracks (they

finally reached Spearman, the end of the line, in 1919.) Elsewhere, short Santa

Fe branches off the main line to Borger (1926) and Skellytown (1927) were built

close to Amarillo. But as of 1927, a vast area of the

north central Panhandle remained void of railroads. Within the large

triangle formed by Amarillo, Stratford and Spearman, oil and gas development

helped provide the final incentive for

railroad construction.

|

By the late 1920s, oil and gas

development north of Amarillo along with significant wheat production farther north in the Panhandle had begun

to interest Rock Island. To serve these areas, they started

construction of a

line north-northeast from Amarillo toward Liberal in 1927. Construction was slowed by the rugged terrain, particularly

crossing the Canadian River, and the tracks did not reach the Oklahoma border at Hitchland until 1929. In addition to serving

mineral industries and

agriculture, the line provided a means of routing freight between Amarillo

and the Midwest, and it potentially served as an alternate route between

Liberal and Tucumcari should Golden State Route operations become

disrupted.

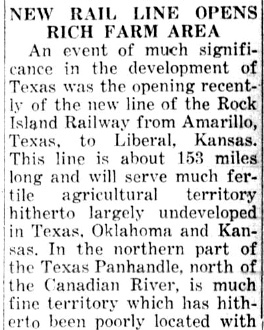

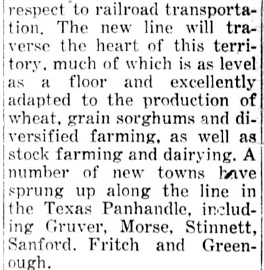

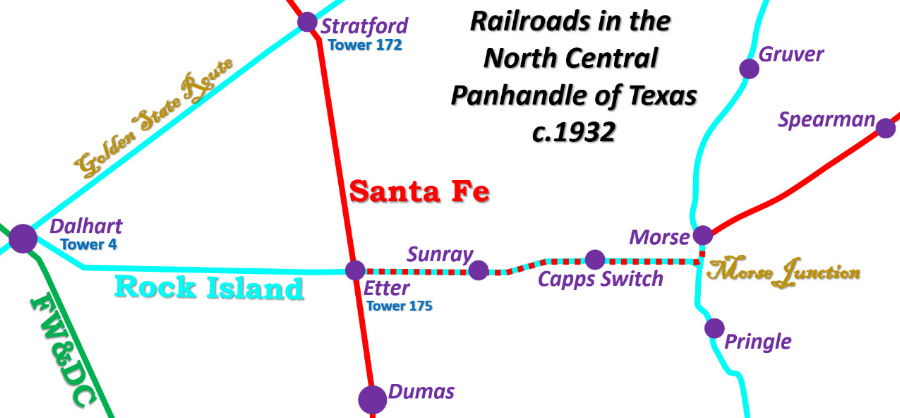

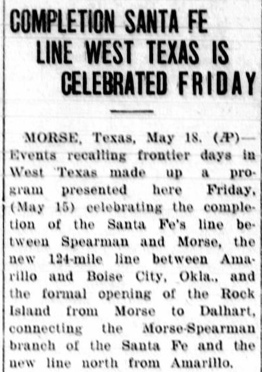

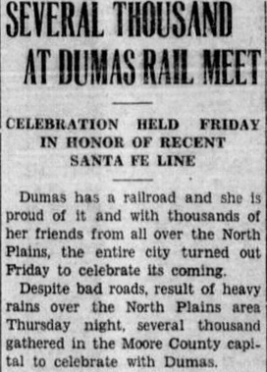

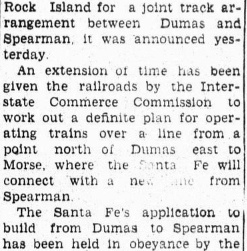

Left and Right:

The Rockdale Reporter of

August 1, 1929 noted that the recent completion of Rock Island's line

between Amarillo and Liberal resulted in the founding of several new

towns in the Texas Panhandle, including Morse. Morse was significant

because it soon became the target crossing point for an extension

proposed by Santa Fe to connect Amarillo with their existing branch line

at Spearman, 18 miles northeast of Morse. |

|

By the fall of 1929, additional railroad development in

the northern Panhandle had become a high priority. Rock Island proposed building a branch line

across the

northern Panhandle between Dalhart, on the Golden State Route, and Morse,

on the newly completed Amarillo - Liberal line, sixty miles apart. This branch

would pass through the oil and gas fields in northern Moore County, twelve miles

north of Dumas, the county seat. The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC)

approved the line, but before Rock Island could start building it, Santa Fe requested ICC approval

of an extensive construction proposal for the northern Panhandle, duplicating to

some extent Rock Island's plan. Santa Fe began with the uncontroversial idea of

connecting its southern main line at Amarillo with its original main line at Las

Animas, Colorado, a north / south route that would go through Dumas, Stratford

and Boise City, Oklahoma. Santa Fe also sought permission to build to Dumas from their

existing branch at Spearman, an extension that would cross Rock Island's

Amarillo - Liberal line at Morse and pass through the heart of the Moore County

oil and gas fields. Rock Island

vigorously opposed this route since it would largely parallel the eastern half

of their ICC-approved line between Dalhart and Morse.

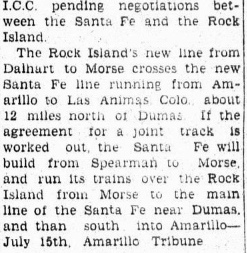

Dalhart and Morse are at the same latitude,

but Rock Island had not proposed to build a due east / west line between them. Instead, the

route went southeast from Dalhart on the abandoned Enid, Ochiltree &

Western (EO&W) right-of-way, a railroad that had been graded from Dalhart to Dumas

but had never become operational. After 5.9 miles on the EO&W, the tracks

turned due east and passed through

farming areas for 33 miles to reach an Apache Refining Co. facility at Altman.

When the Sunray Oil Co. took over the Apache refinery in 1931, the town

name was changed to Sunray (and remains so today.) In 1933, Shamrock Oil and Gas

Co. built its first refinery in Sunray, and soon thereafter, opened its first

gas station there. East of Sunray, the tracks remained on a due east heading

for about three miles and then turned east northeast for approximately three more

miles where they returned to a due east

heading. The reason for this slight jog to the north is undetermined, but it seems

likely to be related to serving particular farming operations. One of these was at Capps Switch, where a siding

was built and where

Skyland Grain now operates

a grain storage facility. About nine miles farther east, the tracks intersected

Rock Island's Amarillo - Liberal line two miles south of Morse, a location that

became known as Morse Junction.

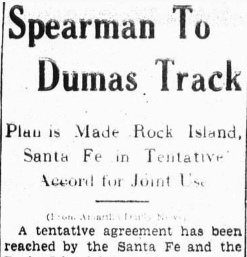

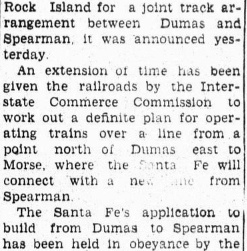

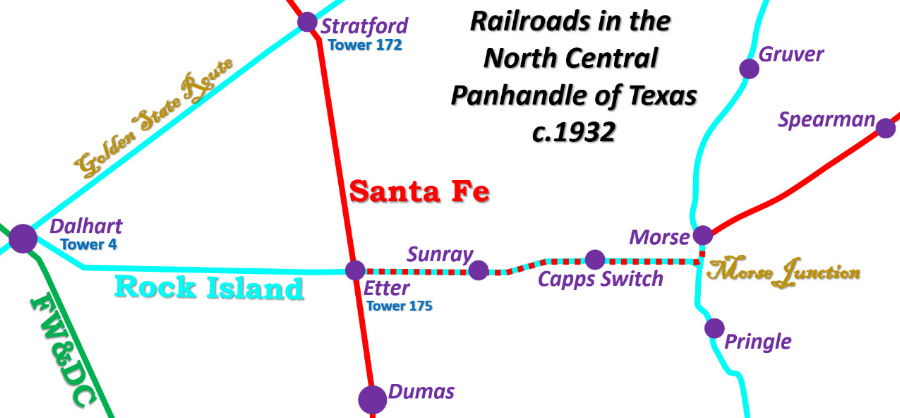

Left:

The Lipscomb Lime Light of July 17,

1930, quoting the Amarillo Tribune,

carried this story about a tentative agreement between Rock Island and Santa Fe

to share the eastern half of Rock Island's new Dalhart - Morse line. Under the plan, Santa Fe would

build from Spearman to Morse and terminate into Rock Island's tracks between

Morse and Morse Junction. From that point, they would have overhead rights on Rock Island's tracks through Morse Junction and westward to the

crossing point of Santa Fe's new line to Las Animas, about twelve miles

north of Dumas. Connecting tracks in the two eastern quadrants would allow Santa Fe trains

from Spearman to access both the original main

line at Las Animas and the southern main line at Amarillo. The tentative

agreement left many details to be determined, and Santa Fe was required to

submit the final plan to the ICC for approval before initiating construction

between Spearman and Morse.

Left:

The Lipscomb Lime Light of July 17,

1930, quoting the Amarillo Tribune,

carried this story about a tentative agreement between Rock Island and Santa Fe

to share the eastern half of Rock Island's new Dalhart - Morse line. Under the plan, Santa Fe would

build from Spearman to Morse and terminate into Rock Island's tracks between

Morse and Morse Junction. From that point, they would have overhead rights on Rock Island's tracks through Morse Junction and westward to the

crossing point of Santa Fe's new line to Las Animas, about twelve miles

north of Dumas. Connecting tracks in the two eastern quadrants would allow Santa Fe trains

from Spearman to access both the original main

line at Las Animas and the southern main line at Amarillo. The tentative

agreement left many details to be determined, and Santa Fe was required to

submit the final plan to the ICC for approval before initiating construction

between Spearman and Morse.

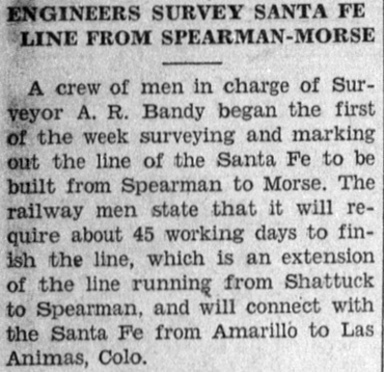

The ICC approved the final agreement in November, and the contract for

sharing the eastern half of Rock Island's Dalhart - Morse tracks was finalized

by the railroads on December 18, 1930. The survey for Santa Fe's extension from Spearman to Morse began

the following week. By the time Santa Fe's construction to Morse was finished,

their line from Amarillo to Las Animas had been completed as far north as Boise

City, Oklahoma where it intersected with other Santa Fe branch lines; the track

from Boise City to Las Animas was finished in 1937. Rock Island's Dalhart -

Morse line had also been completed, hence, new rail service was being celebrated throughout the

northern Panhandle in May, 1931. (Above Left to Right:

Shamrock Texan, December 31, 1930;

Shamrock Texan, May 13, 1931;

Yoakum Daily Herald, May 18, 1931;

Shamrock Texan, May 31, 1931)

As part of ICC's approval of the agreement, on November

13, 1930 they issued "...a certificate of public convenience and necessity to the Santa Fe

railway authorizing the construction of a line of railway from Spearman to a

connection with the Rock Island tracks in Hutchinson County, and also giving

permission to the Santa Fe to enter into a trackage rights agreement with the

Rock Island from the connecting point into Amarillo." (Lipscomb

Lime Light, November 20, 1930, quoting the

Spearman Reporter) [The "connection with the Rock Island tracks in

Hutchinson County" was the location between Morse (Hansford County) and

Morse Junction (Hutchinson County) where Santa Fe's line would terminate, about

3,000 ft. south of the county line.] West of Morse Junction, Santa Fe only

needed trackage rights to the crossing of the Las Animas line, so the language specifying "into Amarillo"

is a bit confusing. The crossing point became known as Etter, named for a Santa

Fe executive, soon to be the site of a Santa Fe water stop and depot. As the

Etter crossing was an important part of the railroads' track sharing agreement,

it seems likely that they also addressed installation of an interlocker.

Regardless of which railroad was the first to actually lay tracks at Etter,

Santa Fe was considered the "second railroad" at the crossing since Rock

Island's permission from the ICC for the Dalhart - Morse line predated Santa

Fe's authorization to build from Amarillo to Las Animas. Under Railroad Commission of

Texas (RCT) regulations, the capital outlay for interlockers at post-1901

crossings belonged

to the "second railroad", hence Santa Fe designed, funded and installed the

signals and interlocker at Etter, and they did so with the intent that the

interlocker be in place by the time both tracks were operational. At the end

of 1931, RCT published a list of

interlocker installations that had occurred during that calendar year. It showed

that a 4-function automatic

interlocking at Etter, identified as Tower 175,

had been commissioned on May 19, 1931, consistent with the celebration dates in

the news articles noted above. The January, 1932 issue of

Railway Signaling reported that the Etter interlocker

was built by Union Switch & Signal Co. and had "8 signals".

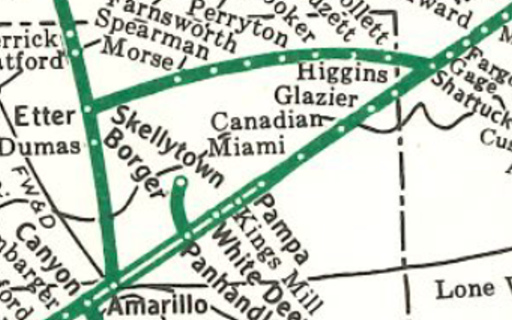

Right:

This 1983 AT&SF System Map shows the Etter - Morse rights (at this point, on

TXNW tracks) treated like any other line in Santa Fe's network, but with no

stops between Etter and Morse (e.g. Sunray, Capps Switch). TXNW inherited Rock

Island's industrial branch running south from Sunray that eventually connected

to a Santa Fe spur (not shown on the map) coming east off the main line north of Dumas

about half way to Etter.

Right:

This 1983 AT&SF System Map shows the Etter - Morse rights (at this point, on

TXNW tracks) treated like any other line in Santa Fe's network, but with no

stops between Etter and Morse (e.g. Sunray, Capps Switch). TXNW inherited Rock

Island's industrial branch running south from Sunray that eventually connected

to a Santa Fe spur (not shown on the map) coming east off the main line north of Dumas

about half way to Etter.

Left:

As of February, 2022, the spur off the BNSF main line has been severed where the

tracks crossed US 287, five miles north of Dumas. Whether the evident road

construction was a factor in the track removal is undetermined. (Google Street

View)

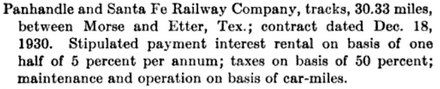

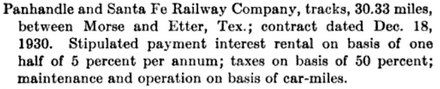

Left: This paragraph from a 1938

ICC Valuation Report discusses Rock Island

property that is "Solely owned, but jointly used with..." the P&SF, providing an

overview of the financial agreement between the two railroads.

Left: This paragraph from a 1938

ICC Valuation Report discusses Rock Island

property that is "Solely owned, but jointly used with..." the P&SF, providing an

overview of the financial agreement between the two railroads.

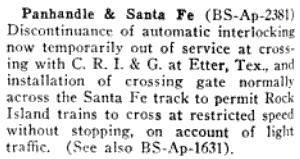

Left:

The February, 1941 issue of Railway Signaling and

Communications reported that the P&SF had filed for permission from the

ICC to make permanent the discontinuance of the automatic interlocking with the

CRI&G at Etter "now temporarily out of service", to be replaced by a

crossing gate "normally across the Santa Fe track to permit Rock Island trains

to cross at restricted speed without stopping, on account of light traffic." The

interlocker was out of service because, as noted the previous year in Volume 21

of The Signalman's Journal, the P&SF

had filed an application with the ICC requesting permission for a "...temporary discontinuance of

automatic interlocking at crossing with C. R. I. & G. Ry at Etter, Tex. on the

Plains Division..." This initial request had been granted, and by early 1941,

Santa Fe was prepared to make it permanent with the installation of a crossing

gate normally lined against their tracks. Santa Fe had insufficient

traffic across the Tower 175 diamond to justify the continued expense of

maintaining an automatic interlocker, even though such expenses were shared with

Rock Island.

Left:

The February, 1941 issue of Railway Signaling and

Communications reported that the P&SF had filed for permission from the

ICC to make permanent the discontinuance of the automatic interlocking with the

CRI&G at Etter "now temporarily out of service", to be replaced by a

crossing gate "normally across the Santa Fe track to permit Rock Island trains

to cross at restricted speed without stopping, on account of light traffic." The

interlocker was out of service because, as noted the previous year in Volume 21

of The Signalman's Journal, the P&SF

had filed an application with the ICC requesting permission for a "...temporary discontinuance of

automatic interlocking at crossing with C. R. I. & G. Ry at Etter, Tex. on the

Plains Division..." This initial request had been granted, and by early 1941,

Santa Fe was prepared to make it permanent with the installation of a crossing

gate normally lined against their tracks. Santa Fe had insufficient

traffic across the Tower 175 diamond to justify the continued expense of

maintaining an automatic interlocker, even though such expenses were shared with

Rock Island.

Below: The

Tower 175 gate was installed and was normally positioned across the P&SF tracks as shown in this photo.

Looking northeast, the P&SF depot is visible (in the distance at left) along

with the P&SF water tower. The Rock Island tracks cross horizontally in the foreground.

The black wiring that snakes up the gate pole connects to the indicator at the

top of the gate to illuminate the gate position for night operation. It was

controlled by the locked metal box near the ground. (Kenneth Moore photo,

date undetermined)

As Santa Fe had funded the

interlocker installation, they also took the lead on requesting permission to

remove it when traffic could no longer justify the maintenance expense.

Since the swing gate was to be normally lined against Santa Fe, it is unlikely that

Rock Island objected; their trains could still cross "at restricted speed

without stopping" and they would no longer have any shared expense for

maintaining the interlocker and signals. The fact that the gate was to be lined against Santa Fe suggests that its north / south trains were

mostly stopping anyway, perhaps for passengers or to handle a cut of freight cars. Thus, the added delay of stopping to

swing the gate was not significant overall, and Santa Fe trains taking either of

the Tower 175 connecting tracks would not have crossed the diamond anyway.

A small settlement

grew up around Etter and in 1940, the census reported 150 people

there. In 1942, the U.S. Government built the Cactus Ordnance

Works immediately north of Etter to manufacture ammonium nitrate for use in explosives

for World War II munitions. The town of Cactus was established, and a few

thousand people worked at the plant during peak years. The railroads benefited

from the freight and passenger traffic generated by the plant and from the families

housed on site. During the war, the plant was modified and partially shut down

as no longer needed, but then it was reactivated to produce components for

fertilizer being shipped to Europe to help restart agriculture in the aftermath

of the war. At various times over many years, the plant produced a diverse array

of commodities including ammonia, nitric acid and additives for aviation fuel.

The plant was closed in the 1980s, but the town now hosts a large meatpacking

plant. With a population over 3,000 residents, Cactus is quite a bit more than

the "wide place in the road" it once

was.

Left:

Overtaken by Cactus, the Etter name is kept alive by at least one business.

The red truck is about to cross the northeast quadrant connecting tracks. Farther

west, the

crossing signals along the highway in the distance mark BNSF's line. (Google

Street View, Jan. 2022)

Left:

Overtaken by Cactus, the Etter name is kept alive by at least one business.

The red truck is about to cross the northeast quadrant connecting tracks. Farther

west, the

crossing signals along the highway in the distance mark BNSF's line. (Google

Street View, Jan. 2022)

In 1960, Rock Island abandoned the first dozen miles of

the Morse branch out of Dalhart, stopping at Wilco, a farming operation about 17

miles west of Etter. This was the first impact

in the Texas Panhandle of Rock Island's attempt to save money by pruning its route

network. By 1964, it was

clear that Rock Island could only survive long term by seeking a merger partner.

The much larger Union Pacific (UP) Railroad agreed to be that merger partner, but the

potential deal was

complicated. Rock Island's financial picture worsened as ICC regulators held

hearings for ten years to take testimony from other railroads opposed to the

merger and to consider UP and Rock Island

counterarguments. With the merger pending, Rock Island continued pruning routes

by abandoning the south end of the Amarillo - Liberal line in 1972, retaining

the tracks north of Stinnett. The merger was approved in 1974, but the

enormity of the plan indicated how radically it would have altered western

railroading. Various terms and conditions specified by the ICC's

administrative law judge were considered onerous by UP, and they chose not to proceed with

the merger. Rock Island went into bankruptcy in 1975; attempts were made, but no

viable recovery plan was ultimately forthcoming. The assets

were liquidated, sold mostly to other railroads; the Golden State Route

was sold to SP in 1979.

On April 8, 1980, the ICC amended a Directed Service

Order they had issued in the wake of Rock Island's suspension of operations wherein individual

railroads had been authorized to serve shippers on an interim basis on specified

Rock Island routes. The amendment authorized Santa Fe to begin serving shippers

on the Etter - Morse line, including the industrial branch line out of Sunray.

(The tracks west of Etter to Wilco were not mentioned, suggesting that the Wilco

shipper may not have been active.)

Santa Fe was also authorized to serve shippers on Rock Island's line between Morse

and Liberal. The tracks from Morse south to Stinnett were not mentioned; again,

there may not have been any active shippers on that track segment. Finally, in 1982, a new railroad, the Texas Northwestern (TXNW), was

founded to acquire Rock Island's branch between Wilco and Morse, plus its

industrial tracks south of Sunray and the remainder of the Stinnett - Liberal

line north to Hardesty, Oklahoma. At this point, Santa Fe's interim service

authorization expired, but they still had their original trackage rights between

Morse and Etter.

|

Left:

This 1982 Santa Fe track chart is oriented with north to

the left, showing tracks adjacent to the Tower 175 crossing.

Right: In 1991, Charles Napp took this photo

facing west toward the Tower 175 crossing. The switch for the single-track northeast connector

is in the foreground. In the distance, the swing gate existed but is not

readily visible. Presumably, its normal position had been changed to be

against the TXNW tracks; to the west, the former Rock Island line to Dalhart was

abandoned although the diamond and gate remained intact. |

|

In 1987, TXNW abandoned the tracks from Morse north to

Hardesty, and from Pringle south to Stinnett, leaving the tracks between Morse

and Pringle as the only remnant of the Amarillo - Liberal line in Texas. In

1990, Santa Fe relinquished its trackage rights between Morse and Etter, and

sold its branch from Shattuck to Morse to the Southwestern Railroad Co. (SWRR) [not to be confused

with the former Southwestern Railway Co at Henrietta.]

SWRR immediately abandoned the tracks between Spearman and Morse.

In 2004, TXNW abandoned the tracks from Capps Switch to Morse Junction, and from

Pringle to Morse, eliminating the last remaining tracks into Morse. In 2007, SWRR

abandoned its tracks from Spearman to Shattuck, Oklahoma, a distance of 85

miles.

Although pipelines now carry most of the oil, gas and refined products in the

vicinity of Etter and Sunray, petrochemical production continues to be a major

contributor to local commerce in northern Moore County. BNSF and TXNW cooperate

to serve the Valero McKee Refinery five miles southwest of Sunray, along with

numerous other industrial and meatpacking facilities in the area.

Above Left: Compare this

November, 2021 view of the site of the Tower 175 diamond with the photo at the

top of the page. (Google Street View)

Above Right: TXNW operates a

huge facility between Etter and Sunray, reportedly the largest private railcar

storage yard in the US, plus cleaning and repair services. (Google

Earth, 2019)

Below Left: This August, 2022 view from the US 287

overpass looks west toward the former Tower 175 crossing. Compare this with the

view from 1991 above. The track arrangement

is indicative of the significant movement of cars on both quadrant connecting

tracks, reflecting the growth of industrial facilities in the Cactus / Etter /

Sunray area. (Google Street View) Below Right:

This August, 2022 image looking east from the US 287 overpass toward Sunray provides another

view of the significant local rail

infrastructure. (Google Street View)

Left:

The Tower 175 diamond was sitting in the weeds a few yards from its historic

location when this photo was taken c.2001. The silver painted hinge post

adjacent to the Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) tracks marks the location of

the swing gate that protected the diamond after the interlocker was removed. The

BNSF tracks are part of a route between Amarillo (to the right) and Las Animas,

Colorado (to the left). The crossing tracks were of Rock Island heritage but

came under Texas Northwestern (TXNW) ownership in 1982 when the last seventeen

miles of the line west of the crossing was

abandoned. The diamond and a short segment of track to the west was retained, presumably

to avoid the expense of reinstalling the diamond if nearby land was acquired for

a rail-served industry. The diamond was removed in the late 1990s or early 2000s.

Left:

The Tower 175 diamond was sitting in the weeds a few yards from its historic

location when this photo was taken c.2001. The silver painted hinge post

adjacent to the Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) tracks marks the location of

the swing gate that protected the diamond after the interlocker was removed. The

BNSF tracks are part of a route between Amarillo (to the right) and Las Animas,

Colorado (to the left). The crossing tracks were of Rock Island heritage but

came under Texas Northwestern (TXNW) ownership in 1982 when the last seventeen

miles of the line west of the crossing was

abandoned. The diamond and a short segment of track to the west was retained, presumably

to avoid the expense of reinstalling the diamond if nearby land was acquired for

a rail-served industry. The diamond was removed in the late 1990s or early 2000s.