Texas Railroad History - Tower 48 - Yarnall

A Crossing of the Southern Kansas Railroad and the Chicago,

Rock Island & Gulf Railway

|

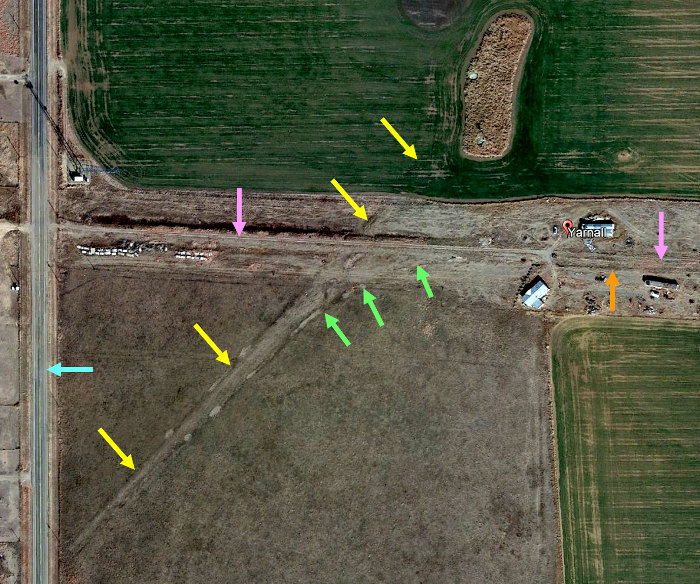

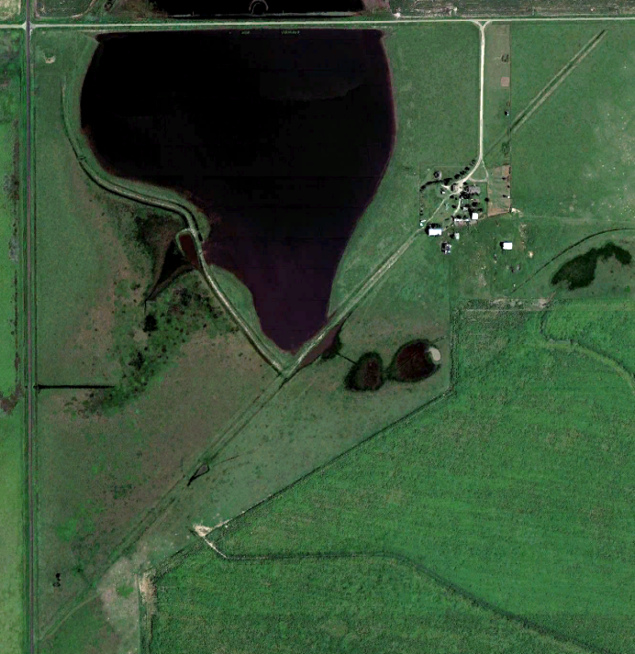

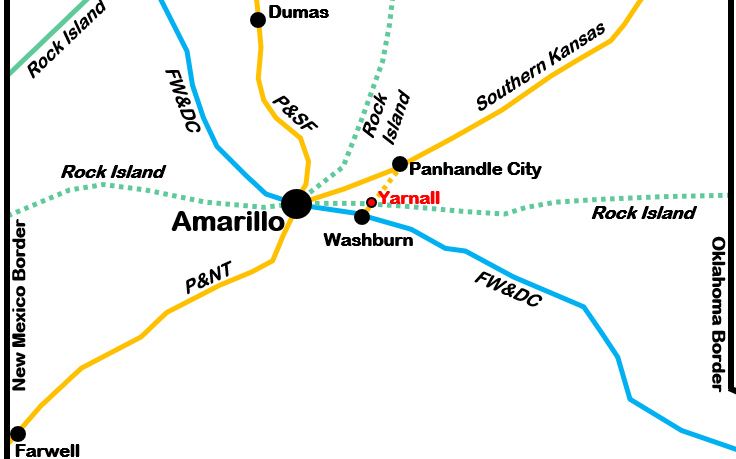

Left:

This 2021 Google Earth satellite view of Yarnall shows the crossing of

the two rail lines (long abandoned) that led to the opening of the Tower

48 interlocker in July, 1904. One of them (yellow arrows) belonged to

the Southern Kansas Railroad (renamed the Panhandle & Santa Fe Railway

in 1914), a subsidiary of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway. The

other set of tracks, owned by the Chicago, Rock Island & Gulf Railway (pink arrows), lasted the longest,

removed in the early 1980s. Tower 48 was operational less than four

years, closing in March, 1908 when the Southern Kansas tracks were

abandoned. There was a connection in the southeast quadrant (green arrows), and the

Rock Island line may also have had a siding at some point (orange

arrow.) Ranch Road 2373 (blue arrow) runs north / south near

Yarnall, and Interstate 40 is off the top of the image, about 0.7 miles

north of the Rock Island grade. Apparently a residence and

scattered outbuildings now occupy Yarnall, which was never an actual

town. There was probably a station there in the early days, but it might

have been simply a repurposed boxcar. By 1908, Yarnall was an unattended

stop on the Rock Island. The source of its name is undetermined, most likely

a landowner's name.

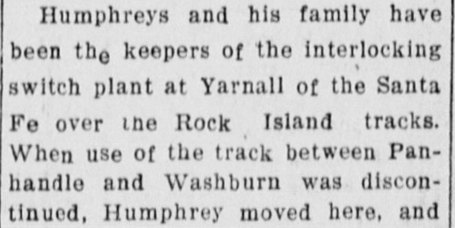

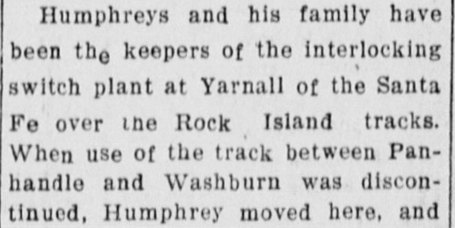

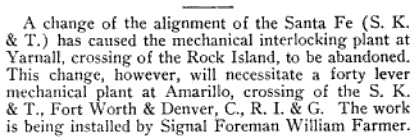

Above: Reporting

on the accidental death at Tangier, Oklahoma of Amarillo resident Mr. P. M.

Humphrey, the Amarillo Weekly Herald

of July 16, 1908 noted that the Humphrey family had been "...keepers

of the interlocking switch plant at Yarnall..." After it

closed, they "took charge" of establishing Tower 75

at Amarillo, commissioned only ten days before the article was published.

From his Tower 75 work and his expected position at Tangier, a Santa Fe

location, the article strongly implies Humphrey was a Santa Fe employee. |

In 1886, the Southern Kansas Railroad, a subsidiary of

the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway, crossed into the northeast Texas

Panhandle from Oklahoma and built southwest into grasslands occupied by large

cattle ranches where bison had once roamed. Construction stopped at a temporary railhead

in Carson County that was initially planned to be known as Carson City. The

railroad decided to change the name to Panhandle City, but a year later, the

name on the new depot was simply "Panhandle", and the name eventually evolved to

drop "City". The community began to

grow; Amarillo had not yet been

founded, and there were no other settlements nearby. The Ft. Worth & Denver City

(FW&DC) Railroad was building from Ft. Worth toward the Panhandle, and many

residents were convinced it would cross the Southern Kansas

at Panhandle City, creating a boom town. The FW&DC had, indeed, verbally agreed

to build through Carson City on its way to the northwest corner of the Panhandle

where it would meet another railroad building south from Denver. The crossing at

Panhandle City failed to materialize as construction issues forced the FW&DC to

bypass the town about fifteen miles to the south.

|

The FW&DC had verbally committed to building to Carson City

(Panhandle City), and there had already been talks of how a connection

could be used to route traffic favorably for both railroads. A group of

related investors chartered the

Panhandle Railway in late 1887 to make the connection by building a line from Washburn,

a stop on the FW&DC, to Panhandle City. A traffic agreement between the two

railroads caused cattle originating on the FW&DC to be routed to

Panhandle City for shipment to the northeast. Drought impacted business,

and the Panhandle Railway was placed in receivership in 1893. For the

next five years, the FW&DC leased it, maintaining service into Panhandle

City and a connection with Santa Fe.

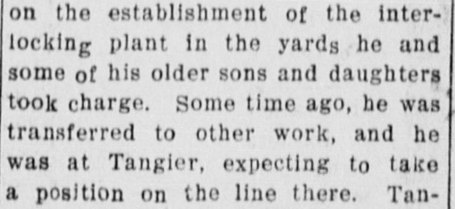

Left: With its new

lease of the Panhandle Railway, the FW&DC wasted no time in promoting

Panhandle City as a new gateway "to the East" for Fort Worth residents (Fort

Worth Gazette, March 24, 1894.) It was a stretch to market

connecting service with Santa Fe at Panhandle City as a route to "All

points in the North and East", but the FW&DC had little else to offer in

those directions since its line out of Fort Worth went northwest to

Denver. It's not clear whether the "close connection" at Washburn

related to schedule or walking distance, but apparently for some trains

"through coaches" were provided. To any of the towns listed,

there could not have been a slower route from Fort Worth than this one.

In April, 1898,

the Southern Kansas took over the Panhandle Railway lease and negotiated

trackage rights on the FW&DC between Washburn and Amarillo. A few months

later in December, the Panhandle Railway was sold by its receivers to a

Southern Kansas employee (its Treasurer) who was acting on behalf of the

railroad to make the purchase. The existing lease was continued until

January 1, 1900, at which point the Panhandle Railway was deeded to the

Southern Kansas. The two-step acquisition process was odd, but

the rationale for leasing (and ultimately owning) the line was

understood by everyone. Eight months earlier, a story in the

El Paso Daily Herald of August 18, 1897

had specifically identified Washburn as the endpoint for a new railroad

to be built out of Roswell, New Mexico by railroad developer James J.

Hagerman. Santa Fe expected to use the Washburn connection as a gateway

to vast agricultural areas well south of Amarillo and into eastern New

Mexico. It's not clear whether the

FW&DC willingly gave up its Panhandle Railway lease, or perhaps it

merely expired, but Santa Fe's

objective was no secret. |

James John Hagerman was an industrialist known best for

developing mines and railroads in Colorado, New Mexico and Texas. [He does not

appear to have been directly related to James Hagerman, the General Solicitor for the Missouri, Kansas & Texas Railroad

who was active in railroading at the same time.] In 1890, Hagerman had built the

Pecos River Railroad from Pecos, Texas to Roswell, New Mexico, and by 1896, he

had begun planning a lengthy extension from Roswell to the Texas Panhandle. The

Pecos River Railroad had mostly been a bust, and Hagerman realized that the

market for the crops grown in the Pecos Valley was to the north. There was also

plenty of cattle to be shipped from ranches in southeastern New Mexico to

stockyards in Kansas City. Hagerman would need a Santa Fe connection to reach

Kansas City, and the obvious connection was at Washburn, although Hagerman

preferred Amarillo, the commercial center of the entire region. The Panhandle

Railway was still in receivership and leased by the FW&DC, so its ultimate fate

was unknown at the time. In January, 1898, Santa Fe agreed to help Hagerman

finance his idea. Santa Fe had already surveyed routes southwest out of Washburn

when they first had looked at building southwest from Washburn in 1891. Hagerman

attempted to renew the plan with landowners in Washburn, requesting half of the

townsite be granted to his railroad in exchange for creating what would

undoubtedly become a major junction with rails in four directions. He also

wanted a $20,000 bonus. Washburn drove a hard bargain, only willing to grant

right-of-way and land for depot facilities. After all, where else could Hagerman

go to reach the Santa Fe?

From a Pecos River crossing immediately north of

Roswell, all the way to Washburn, Hagerman's planned right-of-way ran on a generally straight 55

degree northeast heading, passing barely north of Palo Duro Canyon, and

conveniently serving the towns of Portales, New Mexico and

Canyon, Texas. Where the right-of-way entered Texas

(the future border town of Farwell), the surveyors

had elected to stay north of the Tierra Blanca Creek drainage, and this brought

the line slightly farther north than needed for a direct line into Canyon. Near

Umbarger, the heading was adjusted slightly to the east toward Canyon; a second

adjustment on the outskirts of Canyon sent the right-of-way due east through the

town. The survey presumably returned to a 55 degree northeast heading from Canyon

to Washburn, but the details are lacking because that segment was never built.

At some unknown date (and certainly no later than

the summer of 1897), Amarillo civic leaders

got wind of Hagerman's plan and were absolutely

flabbergasted at the possibility of a

major railroad, Santa Fe, bypassing Amarillo a mere fifteen miles to the

east. Though Hagerman was building it, Santa Fe was clearly the heavyweight in

this enterprise, so Amarillo dispatched Squire Madden, a well-known local

attorney, to meet with Santa Fe officials at their Chicago headquarters. The

date of this meeting is undetermined; the

Handbook of Texas asserts that it was sometime in 1896. Madden's

mission was successful as Amarillo agreed to pay $20,000 for the privilege of

having Santa Fe move the connecting point to Amarillo, even though it had no tracks there. Madden was celebrated for his role in furthering Amarillo's

growth, and he subsequently became the "go to" lawyer for railroad

companies in the Texas Panhandle.

Right: This article in the

Fort Collins (Colorado) Courier of

March 24, 1898 narrows the timeframe of when Santa Fe and Hagerman

changed the connecting point to Amarillo (only fifteen miles from

Washburn,

not "thirty-five.") The actual decision was probably a few months

beforehand, time used for revising the right-of-way and securing

easements. Modifying the alignment for a straighter route into Amarillo

would have meant bypassing Canyon, a legitimate population center and

the county seat of Randall County. Thus, the survey was maintained into Canyon as planned and then turned abruptly north

to Amarillo. Unless the railroads had been truly perplexed, the date of

this public announcement suggests that Squire Madden's meeting with

Santa Fe was more recent than 1896. As for the extension between

Amarillo and "the

main line of the connecting road" (at Panhandle City), it was built

"immediately" ... if "immediately" means "ten years from now". |

|

|

Newspapers began describing Hagerman's line as a Santa Fe extension.

On March 19, 1898, Hagerman obtained a Texas charter for the Pecos &

Northern Texas (P&NT) Railroad to own the Texas portion of his new

enterprise in compliance with Texas' railroad ownership laws. Hagerman's construction began at Amarillo and went south; it was much

faster to ship rails and other materials from

Galveston to Amarillo rather than

to Roswell (although some later construction commenced from Roswell.) The

Lampasas Leader of July 29, 1898

carried a story describing business in Amarillo as "quite lively now, owing to the

cattle trade and the great influx of railroad men employed on the

extension of the Pecos Valley & Northeastern railway." The

newspaper predicted

December 15th as the date of the first train, and that date appears to have

been achieved, or nearly so, at least between Amarillo and Portales.

Hagerman sold out to Santa Fe in 1901, an outcome that seems to have

been simply part of the plan all along.

Left: The El Paso

Daily Herald of February 13, 1899, quoting the

Roswell Register, reported that

eighteen miles north of Roswell, James Hagerman's wife would drive a gold spike signifying completion

of the line between Roswell and Amarillo. |

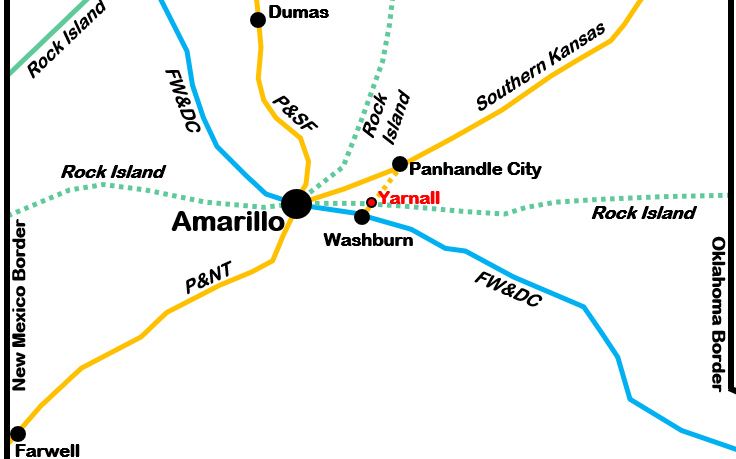

In 1902, the Choctaw, Oklahoma and Gulf Railroad's main line from Memphis to

Oklahoma City, continuing into western Oklahoma, was extended across the Texas

border. The work was performed under a

Texas-chartered subsidiary, the Choctaw, Oklahoma & Texas (CO&T) Railroad,

that planned to build to Amarillo.

The CO&T

proceeded due west from the border, passed through (and helped re-establish) the

community of Shamrock, and continued until it

reached the Southern Kansas tracks between Washburn and Panhandle, 95 miles from

the Oklahoma border. A junction was established at a place called

Yarnall, and

the CO&T negotiated trackage rights with the Southern Kansas and the FW&DC to

route trains from Yarnall into Amarillo via Washburn.

In 1904, the Chicago, Rock

Island & Gulf Railway, a Texas-based subsidiary of the Rock Island system,

acquired the CO&T and extended its tracks eighteen miles west into

Amarillo. This created a crossing of the Southern Kansas tracks at Yarnall and a

corresponding need for an

interlocker. To control this crossing, Tower 48 was commissioned on July 13, 1904

by the Railroad Commission of Texas (RCT) incorporating a

12-function mechanical interlocking plant. This was the minimum interlocker for

a simple crossing of two railroads, consisting of a home signal, a distant signal

and a derail in each of the four directions.

For some period of time,

perhaps Tower 48's entire existence, Santa Fe appears to have employed the Humphrey

family to operate and maintain

(O&M) the tower. Given the

remote location (especially in 1904), it is reasonable to assume that the entire family was living at or

near Yarnall, possibly in a residence supplied by Santa Fe. If so, some or all

of the residential costs might also have been included as a component of the

tower's O&M expenses. Santa Fe being responsible for staffing the tower would typically imply that it

was a "Santa Fe tower", i.e. that Santa Fe had designed it and managed its

construction. But under RCT rules for post-1901 crossings, Rock Island

would have been responsible for the capital outlay for the tower because Rock

Island had

been the second railroad, i.e. the one that created the crossing. (For crossings

that already exited as of 1901, the railroads split the capital costs equally.) Typically, when a single railroad

funded a tower's design and construction, it would also take O&M responsibility.

Apparently, at least one of these "typical" axioms did not apply to Tower 48.

Regardless, the railroads would have shared O&M expenses on equitable basis,

usually the allocated share of

interlocker functions (in this case, each railroad had six of the twelve

functions, 50%.)

|

|

In 1908, Santa Fe opened the Belen Cutoff

across eastern New Mexico, creating an alternate route for a portion of its

transcontinental main line between Kansas City and Los Angeles. The eastern

terminus of the Belen Cutoff was the existing Roswell - Amarillo line at Texico, across the border from Farwell. The new town of Clovis was built nearby

to host a major yard and maintenance facility. As Santa Fe was preparing

for substantial long distance traffic moving through Amarillo, continuing to use the route from Amarillo

to Panhandle City via Washburn no longer

made sense (not that it ever did after the P&NT line opened.) Instead, Santa Fe extended the Southern Kansas tracks from Panhandle

City directly into Amarillo, a distance of 25 miles. The tracks between

Panhandle City and Washburn were immediately abandoned, eliminating the Rock

Island crossing at Yarnall and the need for Tower 48.

|

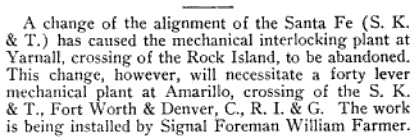

Left:

The abandonment of the tracks between Panhandle City and Washburn

removed the crossing of the Rock Island at Yarnall, resulting in the

closure of Tower 48. This note from the June, 1908 issue of The Signal

Engineer billed the closure as resulting from a "change of

the alignment". That characterization is slightly misleading; it was not

really a track realignment since the endpoint at Washburn was completely

eliminated. One consequence of

the new line into Amarillo was the need for a new interlocker (Tower

75) to control Santa Fe's crossing of the FW&DC and the Rock Island.

The 1909 RCT Annual Report stated that Tower 48 was "abandoned March 28,

1908 and crossing removed". |

Because the Belen Cutoff opened in July, 1908,

about three months after Tower 48 closed, the tower never experienced the

traffic increase that undoubtedly occurred. Whether the tower ever saw much

traffic at all is undetermined, but RCT records show that an average of only

twelve movements per day passed

by Tower 48 in June, 1906. The daily average for the prior

twelve months was ten. Among all active interlockers at that time, Tower 48 was tied with

Tower 46 in Hubbard for the lowest average daily count

of train movements for the twelve months ending June, 1906. Unfortunately, RCT

never published similar statistics again.

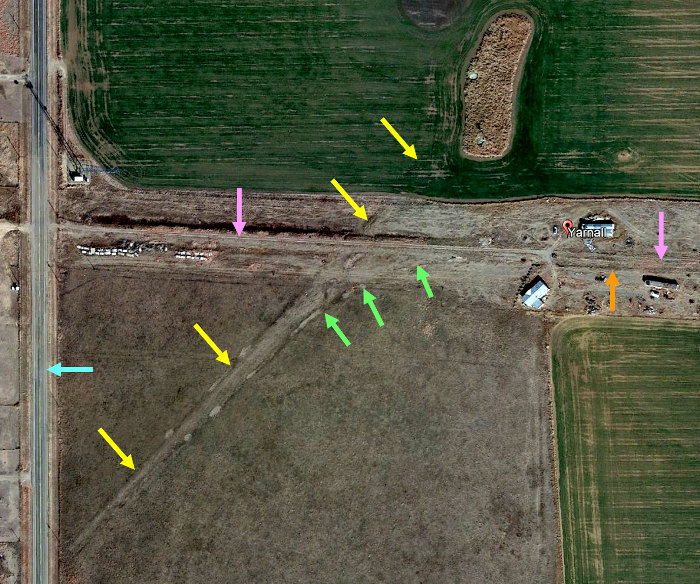

Above: Looking east from Ranch Rd. 2373, Google Street

View captured this May, 2021 image of the former Rock Island grade at Yarnall.

The Southern Kansas crossing was about halfway to the residence. Tower 48,

whatever it was, would have been visible from this view during the three years

and eight months of its existence. Was Tower 48 a typical manned, two-story

tower similar to other Santa Fe towers built in the same era, e.g.

Cameron, which opened a week later? It seems

doubtful that a two-story structure was necessary; there was only one connecting

track and certainly nothing to inhibit visibility in any direction. But even if

it was a single story structure, it seems likely that Tower 48 was manned by an

operator. Cabin interlockers were single-story unmanned huts, but none are known

to have been established earlier than 1915. The newspaper article states that

Humphrey and his family were the "keepers" of

the tower at Yarnall (and it was definitely a family affair; the article

mentions that Humphrey's "older sons and daughters" also helped him with the

Amarillo interlocker.) The family aspect, along with the word "keepers", tends

to imply they were all living together at or near Yarnall, presumably because

they operated the tower in addition to maintaining it. Performing maintenance

duties alone would not take a

family, nor would it necessarily require residing at or near the tower.

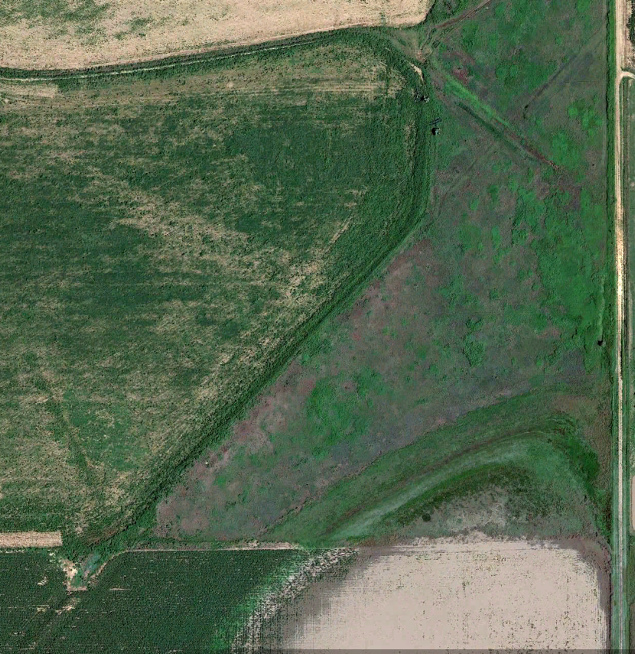

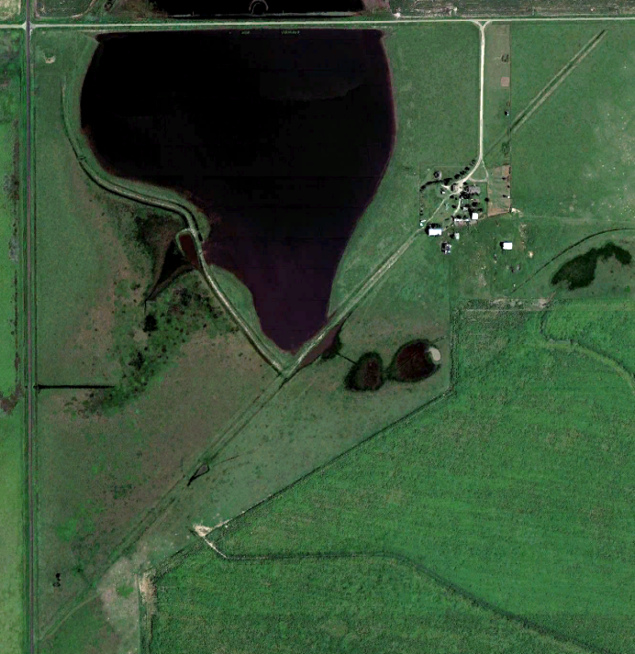

Above: This 2018 satellite

imagery shows what has been identified as the grade of the Panhandle Railway

between Washburn and Panhandle City using geographic cross-references from 1953 historic aerial imagery.

The 1953 imagery reveals the grade to have run in a straight line on a ~ 43

degree heading for the entire distance between the

two endpoints. The most obvious section still visible is at left,

centered at 35 14 47 North, 101 29 57 West. The grade runs

diagonally across the image from lower left to upper right on its northeast heading, passing through what appears to be a ranch headquarters. Another location

is at right centered at 35 16 08 North, 101 28 25

West showing the grade following the same heading. Through the middle

of the image, it appears to form a portion of a pasture boundary.

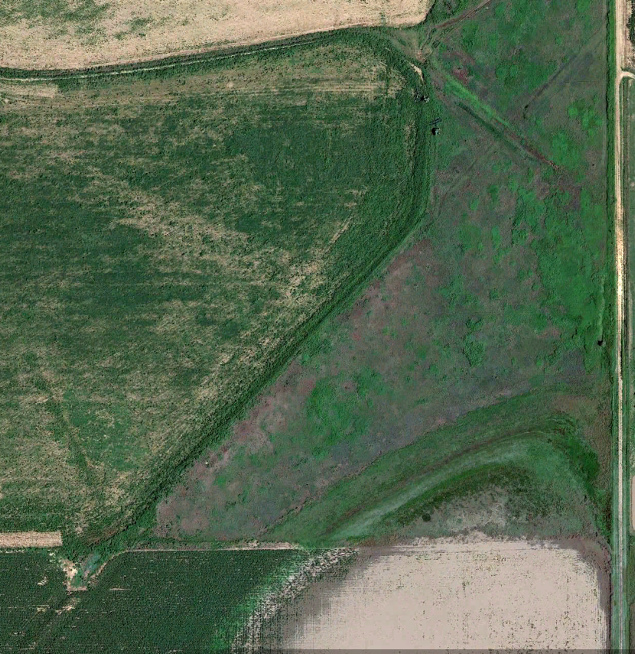

Below Left: This 1953 image

((c)historicaerials.com) has been annotated to highlight the original connection

of the Panhandle Railway into the FW&DC at Washburn. Abandoned 45 years earlier,

the grade (blue arrows) branches into a wye with east (pink) and west (yellow)

legs. The wye (at 35 10 44 North, 101 34 36 West) likely connected into a siding

rather than to the main line; evidence of that siding might still have been

visible (red) in 1953. A siding or spur (orange) comes off the FW&DC

main line (green.) The roadway is U.S. Highway 287.

Below Right: Disturbed earth (yellow arrows) on the

southwest side of Panhandle (formerly Panhandle City) on this 2016 Google Earth

satellite image shows the Panhandle Railway grade approaching what is now a

Burlington Northern Santa Fe

double track main line (across the highway) on the original right-of-way of the

Southern Kansas. The grade is located at 35 19 37

North, 101 24 24 West.