Texas Railroad History - Tower 130 - Grand Saline

A Crossing of the Texas Short Line Railroad and the Texas & Pacific

Railway

Above Left: This caboose on

static display in Grand Saline is of Union Pacific (UP) heritage, but it is painted

to commemorate the role of the Texas Short Line

(TSL) Railroad in the history of Grand Saline. (Google Street View 2013)

Above Right: The original TSL depot in

Grand Saline featured a two-story bay window. (Grace Museum collection, Abilene)

With a name like Grand Saline, salt must be part of the

story. A salt water marsh in this area of Van Zandt County had long been used by the Caddo and Cherokee

tribes to

create salt by evaporation. By 1845, a commercial salt works had been built by

John Jordon at a site he called Jordan's Saline. Salt was a major trading

commodity because it was the only practical means of preserving meat. Jordan's

land changed hands, and ended up owned by Samuel Richardson prior to the Civil

War. Richardson

donated acreage to the Texas & Pacific (T&P) Railway for a townsite and water

stop as it built west from Marshall toward Dallas in 1872. The T&P's chief

engineer, Grenville M. Dodge, laid out much of the town and named the station

Grand Saline. Jordan's Saline lost its post office and was soon overtaken as

Grand Saline expanded.

Salt production increased at Grand Saline, and it

eventually included direct mining of the rock salt in the enormous salt dome

that sits beneath the area. Transportation provided by the T&P helped to foster

salt commerce which led to investments for improved salt production methods,

further increasing shipments of finished salt. Producing salt required

substantial amounts of energy, so the discovery of lignite deposits near the

community of Alba was a potential boon for the salt industry. Alba was located

on the Missouri, Kansas & Texas (MK&T, "Katy") Railway about nine miles

northeast of Grand Saline. The Katy tracks had been built on a northwest /

southeast alignment between Greenville and

Mineola in 1881, and the line intersected

the T&P at Mineola, thirteen miles east of Grand Saline. Rather than ship coal

from Alba to Mineola and then back west to Grand Saline, J. B. Seeger and others

saw the opportunity for a direct rail line between Alba and Grand Saline. Seeger

owned coal mines at Alba and he envisioned a beneficial flow of commodities in

both directions: coal moving south to Grand Saline to power salt production,

finished salt moving north to Alba for direct shipment to Midwest markets on the

Katy. To effect this

opportunity, the Texas Short Line (TSL) Railway was chartered on February 28,

1901 by Seeger and other investors to build between Alba and Grand Saline.

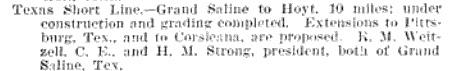

Left:

Railway Age, March 21, 1902. The first 4.5

miles of track north from Grand Saline was completed in 1902, and the remaining

4.9 miles was completed in 1903. The TSL did not build into Alba; instead, the

Katy connection was made a half mile southeast of Alba at Hoyt. Nor did the TSL

connect with the T&P in Grand Saline; there was simply no need, thus its tracks

remained north of the T&P.

Left:

Railway Age, March 21, 1902. The first 4.5

miles of track north from Grand Saline was completed in 1902, and the remaining

4.9 miles was completed in 1903. The TSL did not build into Alba; instead, the

Katy connection was made a half mile southeast of Alba at Hoyt. Nor did the TSL

connect with the T&P in Grand Saline; there was simply no need, thus its tracks

remained north of the T&P.

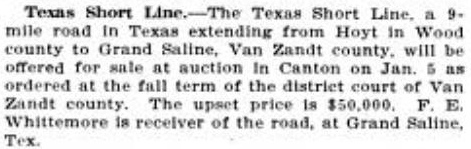

Right:

Railway & Engineering Review, December

26, 1908. Besides salt, coal and occasional carloads of cotton, the TSL carried

passengers via the Katy connection at Hoyt, but little else. Business was

acceptable for a few years, but in 1908, the TSL went into receivership. The

bankruptcy court announced that the TSL would be put up for sale by auction on January 5, 1909 at

Canton, the county seat of Van Zandt County.

Right:

Railway & Engineering Review, December

26, 1908. Besides salt, coal and occasional carloads of cotton, the TSL carried

passengers via the Katy connection at Hoyt, but little else. Business was

acceptable for a few years, but in 1908, the TSL went into receivership. The

bankruptcy court announced that the TSL would be put up for sale by auction on January 5, 1909 at

Canton, the county seat of Van Zandt County.

Prior to the

auction, a Grand Saline general store merchant, T. B. Meeks, gathered additional

investors and was able to settle all of the liens against the TSL.

It was

released from receivership without being sold. What was behind this sudden

largesse that was able to keep the TSL solvent?

|

Left:

Sulphur Springs Gazette, January 22, 1909, quoting the

Quitman Democrat

Before the end of January, the receivership was

formally dismissed at Canton and one of the participants at the county

courthouse was "J. W. Smart,

cashier of the First State Bank of Quitman". It seems likely that

a major portion of the new money that Meeks had rounded up to save the TSL came from the town of Quitman, county seat

of Wood County. Alba and Mineola were both in Wood County and both had

rail service, but Quitman did not. Quitman was only ten miles due east

of Hoyt, so the idea of extending the TSL to Quitman was plausible, and

a survey was apparently well underway.

Right: Sulphur

Springs Gazette, February 19, 1909

The TSL made no

secret of their intent to build beyond Alba, but they were less

forthcoming with a precise plan. In response to an inquiry from the

Board of Trade at Cooper, Texas, Meeks penned a letter

stating "We have not fully decided as to where we will build. Whether on

to Quitman, in the direction of Cooper and Paris, or whether we go

direct to Sulphur Springs. It greatly depends on the rights of ways and

donations that we receive from points along the line..."

Ultimately, the TSL was never extended beyond Alba. |

|

Instead of building beyond Alba, the TSL's attention

turned in the other direction. In 1890, direct mining of the rock salt in the

dome beneath Grand Saline had begun, yielding some of the purest salt to be

found anywhere. By 1910, rock salt mining had become a major operation, the

primary source of salt production in Grand Saline. The mine also supported

evaporative production methods wherein water was pumped underground to dissolve

the salt and then pumped back to the surface to be boiled to produce a salt

slurry that was then dried to create finished salt. Unfortunately for the TSL,

the mine was located south of the T&P tracks, hence the TSL did not serve the

mine directly. To rectify this situation, the TSL applied to the Railroad

Commission of Texas (RCT) for permission to build across the T&P tracks in Grand

Saline with a spur track leading into the mine. At least one of the coal mines

near Alba had come under ownership of the salt company, so the ability to ship

coal directly to the mine had gained in importance.

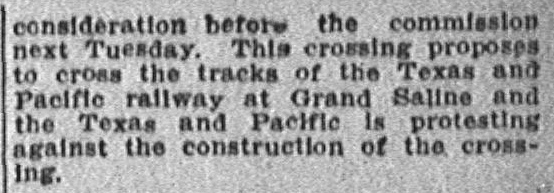

Austin Statesman, April 5, 1910 |

Austin Statesman, May 7, 1910 |

Austin Statesman, May 14, 1910

|

Above: The TSL

appeared before RCT to argue its case for a grade crossing of the T&P at Grand

Saline. The T&P opposed the TSL's application, although the basis of their

opposition is undetermined. The fact that the T&P did not already have a spur to

the mine may have weighed against their case, depending on whether the mine had

sought such service. RCT granted the TSL application and a spur track across the

T&P was built.

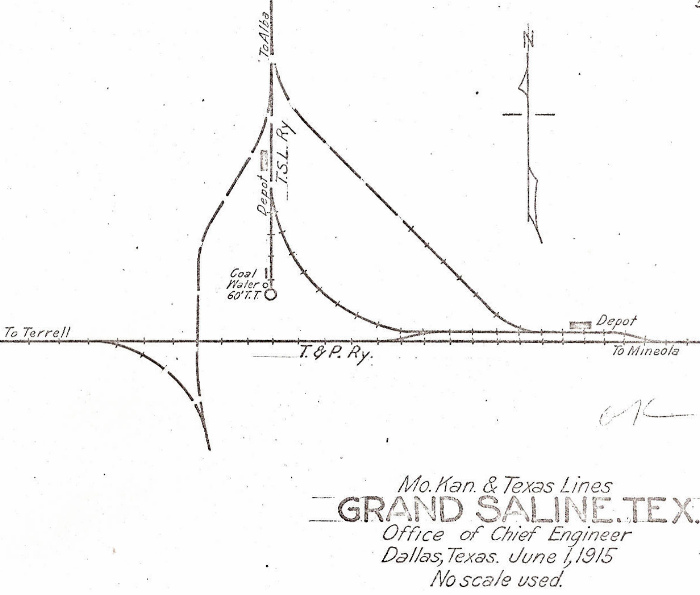

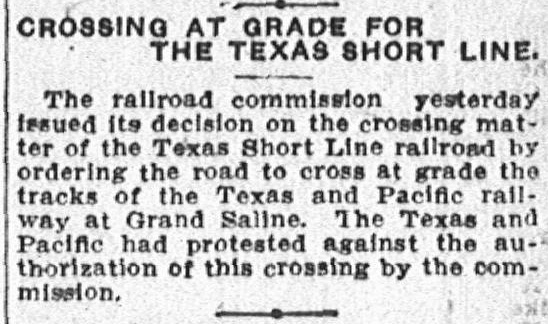

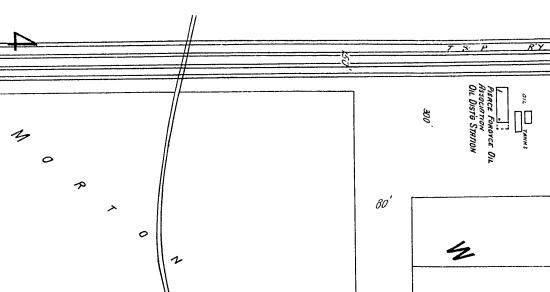

Left:

This 1915 track chart (courtesy Ed Chambers) from the Katy's Office of the Chief

Engineer shows the TSL spur track crossing the T&P main line. The chart does not

show that the track continued south and back to the east to reach the mine which

was (and still is) located about a mile south of the T&P main line.

Left:

This 1915 track chart (courtesy Ed Chambers) from the Katy's Office of the Chief

Engineer shows the TSL spur track crossing the T&P main line. The chart does not

show that the track continued south and back to the east to reach the mine which

was (and still is) located about a mile south of the T&P main line.

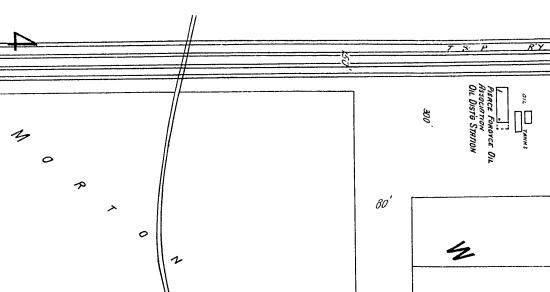

The

track chart also shows the T&P connecting to the mine spur, but that connection

does not appear on the 1923 Sanborn Fire Insurance map of Grand Saline (below).

This was most likely a simple oversight on the part of the cartographer as the T&P would have had no incentive to remove an

existing connection to the mine spur.

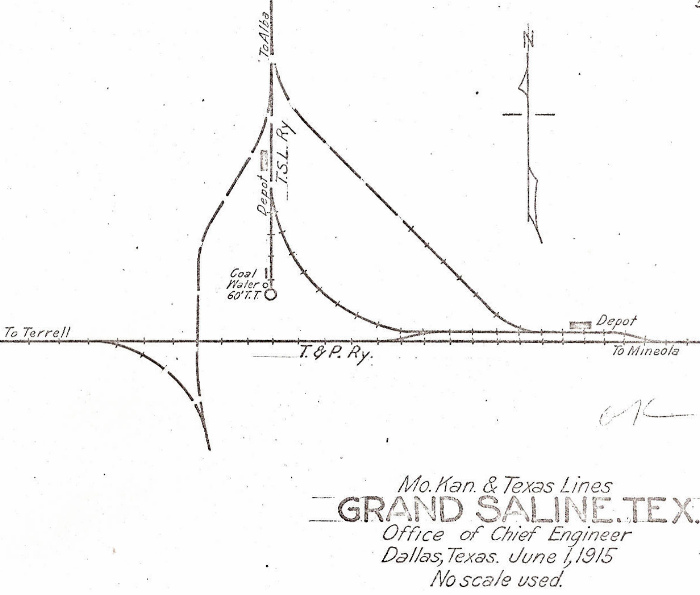

Note that the "Morton" annotation

on the map reads in full "Morton Salt Cos Salt Field". Around 1920, Morton Salt

Co. acquired the salt mine and all of the salt works in Grand Saline, and it

continues to operate the mine today. Lignite was phased out by Morton in

1941 and replaced by natural gas as the principal energy source for the salt

works.

from Sheet 6, Sanborn Fire Insurance map of Grand Saline, April, 1923

RCT construction and abandonment records published by

Charles Zlatkovich in 1980 contain two 1922 entries for abandonments by the TSL.

One is for 1.4 miles between Grand Saline and "Salt Works". The other is for

1.41 miles between Alba and "Coal Mine". The precise circumstances that produced

these records are undetermined. It is not surprising that tracks near the coal

mines would be abandoned; lignite mines depended on relatively inexpensive

surface mining, so mines would close when the easily accessed surface vein had

played out. The abandonment to "Salt Works" is much harder to understand,

especially since the only known spur continues to exist.

RCT had

approved the TSL crossing of the T&P at grade in 1910, but the crossing was

uncontrolled, hence all trains had to stop before passing over the diamond. The

crossing was most likely gated per RCT regulations, and the gate would normally

have been positioned against the TSL. While the presence of a gate did not

eliminate the legal requirement to stop for trains approaching an open gate,

there is evidence that this rule was not enforced for gated crossings located

near a depot, as the Grand Saline crossing was. Trains were generally stopping

at the depot anyway, hence they were already operating at a restricted speed

near the gated crossing.

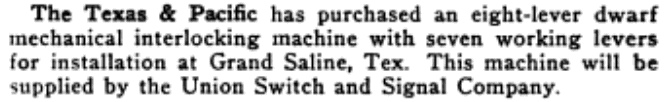

The T&P had by far the most to gain from the

installation of an interlocker to control the crossing, and on February 20, 1926, RCT commissioned an

eleven-function mechanical interlocker housed in a trackside cabin at the Grand

Saline crossing. The interlocker was formally designated Tower 130 by RCT. The

impetus behind the establishment of this interlocker was

most likely a decision by the T&P to improve train speeds through Grand

Saline. By the mid 1920s, T&P trains could travel longer distances without a

water stop, so a regular stop at Grand Saline had become unnecessary for many

trains. Similarly,

express passenger trains would not normally stop at a small town like Grand

Saline.

|

Left:

Railway Signaling, October,

1925 |

Cabin interlockers did not become common in Texas until the mid

1920s. They were used in situations where a heavily used line crossed a lightly

used line, the Grand Saline crossing being a classic example. Such crossings

could not justify the operating expense of a manned tower since the signals were

almost always lined to allow continuous movements on the busier line. There

would literally have been nothing for the operators to do except on the

relatively rare occasions that a train on the lightly used line needed to cross.

For the Tower 130 cabin interlocker, the signals would always have been lined to

allow continuous movements on the T&P. They would be reversed only during the period that

a TSL train was actually

crossing the diamond, and thus, it was a crewmember of the TSL train that

operated the controls in the cabin. Once the crossing was complete,

the signals would be returned to the normal position for continuous movements on

the T&P.

From a maintenance perspective, cabin interlockers were

unique in that the railroad that actually operated the controls was from the

lightly used line, whereas the railroad that maintained the interlocker was

typically the one with the busier line. The busier railroad had the stronger

incentive to ensure that the signals, controls and diamond were maintained in

excellent condition. Their higher train volume would cause them to experience a more significant

negative impact if the

crossing became uncontrolled for any period of time due to maintenance issues.

|

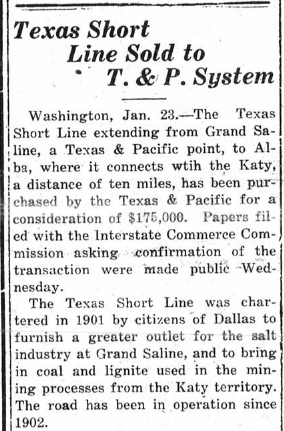

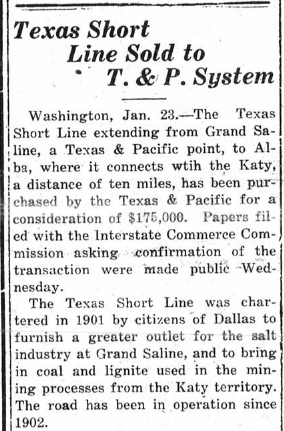

Left: Mount Pleasant

Daily Times, January 24, 1929

In early 1929, the T&P purchased the TSL

but continued to operate it as a separate subsidiary. It seems highly

likely that the purchase was a defensive move related to efforts that occurred throughout the 1920s to consolidate

railroads into more efficient "systems." In the Transportation Act of

1920, Congress directed the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to

promote and plan consolidation of U.S. railroads into a limited number

of "systems". The ICC responded by hiring economist William Z. Ripley to

develop a plan. The so-called "Ripley Plan" announced several such

systems, but there was push-back by the railroads which did not

necessarily agree with the allocations made by Ripley. By 1926, Leonor

F. Loree, a long time rail executive and head of the Delaware & Hudson

Railroad, had gained control of the Katy, the St. Louis Southwestern

("Cotton Belt") and the Kansas City Southern (KCS), all of which

operated throughout the southwest, each having a significant presence in

east Texas. Loree proposed a Southwest System that would consolidate the

Katy, KCS and Cotton Belt into one major railroad system operating in

the southwest.

Right:

Grand Saline Sun, January 31,

1929

Meeks appeared before the ICC to testify against the

Loree plan, asking that the TSL either be included within it or granted

better division rates for traffic exchanged at Alba. The American

Short Line Association was lobbying the ICC to require major system

consolidations to account for the interests of the short line railroads.

The T&P's purchase was simply to ensure that no

other major railroad system gained a foothold at Grand Saline by

acquiring the TSL. |

|

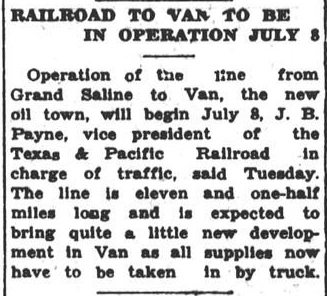

Later in 1929, oil was

discovered near Van, a community located eleven miles southeast of Grand Saline.

The T&P tracks at Grand Saline were reasonably close to Van, but the

International & Great Northern line between Mineola and Lindale was a similar

distance northeast of Van. To get there first, the T&P funded the TSL to build 11.5

miles of tracks south from Grand Saline to Van.

Later in 1929, oil was

discovered near Van, a community located eleven miles southeast of Grand Saline.

The T&P tracks at Grand Saline were reasonably close to Van, but the

International & Great Northern line between Mineola and Lindale was a similar

distance northeast of Van. To get there first, the T&P funded the TSL to build 11.5

miles of tracks south from Grand Saline to Van.

Right:

The Van News (published at Wills Point),

July 4, 1930

By the spring of 1930, the Van oil field was producing

twenty thousand barrels of oil per day. Shipping the oil by rail became an

option when the TSL line was completed in early July. But before the end of the

year, two pipelines had reached Van and oil shipments by rail declined. While

the T&P undoubtedly benefited from the movement of people, supplies and

equipment to and from Van, the prompt introduction of pipelines prevented the huge

bonanza for the T&P that otherwise might have occurred.

The Van oil field

peaked in 1932 with more than seventeen million barrels of oil produced.

Production declined into the 1940s, then ramped back up to over ten million

barrels per year during World War II. The final decline began in the early

1950s, and production in the Van field ended in 1959. The TSL tracks to Van were

abandoned in 1962. Successful secondary production methods revitalized the field

in the 1970s, and the Van field continues to produce oil and natural gas at

modest levels today. The abandonment of the tracks to Van ended the life of the TSL. The

tracks from Grand Saline to Alba had been abandoned in 1959, so there was

literally nothing left.

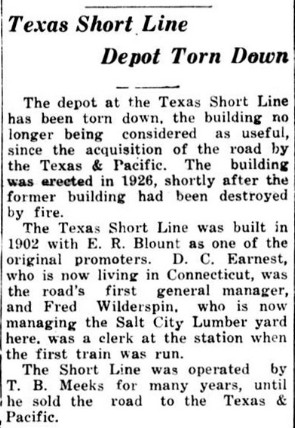

Far

Left: TSL depot, 1902 (Chino Chapa coll.)

Far

Left: TSL depot, 1902 (Chino Chapa coll.)

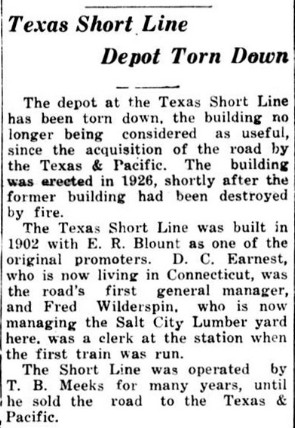

Near

Left: Grand Saline Sun,

February 27, 1936

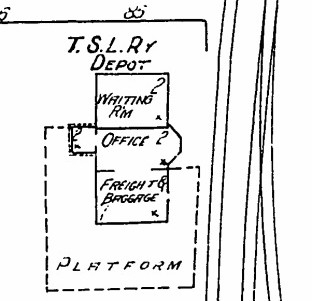

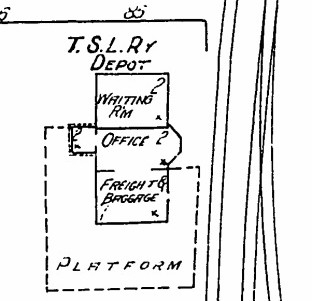

Below:

Sanborn Fire Insurance map, Aug. 1909

By 1930, Missouri Pacific (MP) owned 75% of the T&P's

stock but did not exercise management control. The two companies worked

cooperatively for many years as MP gradually increased its ownership of the T&P,

reaching more than 96% by the end of 1974. In 1976, the T&P was fully merged

into MP. In 1982, MP was acquired by UP, but it continued to operate under the

MP name until it was fully merged in 1997.

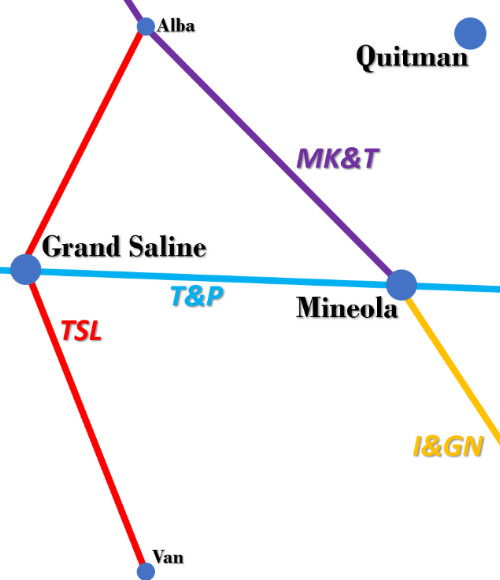

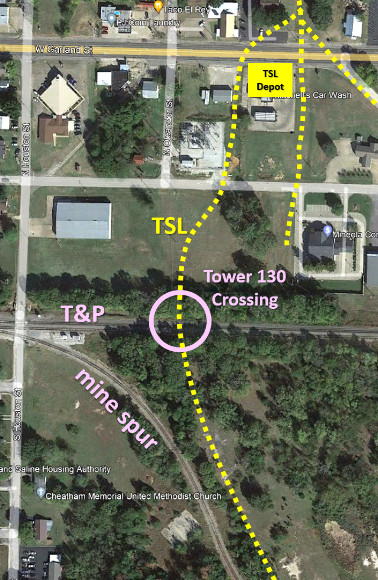

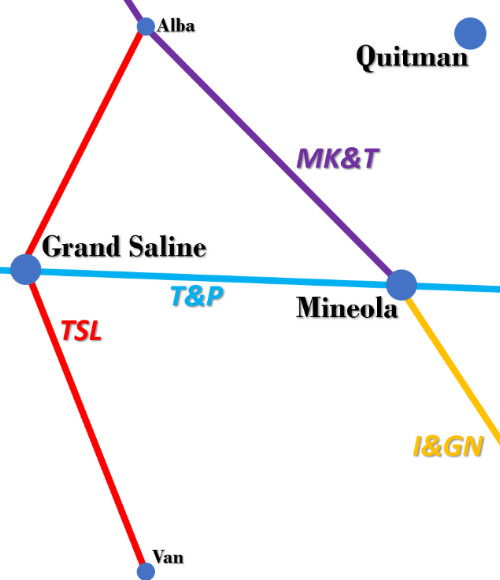

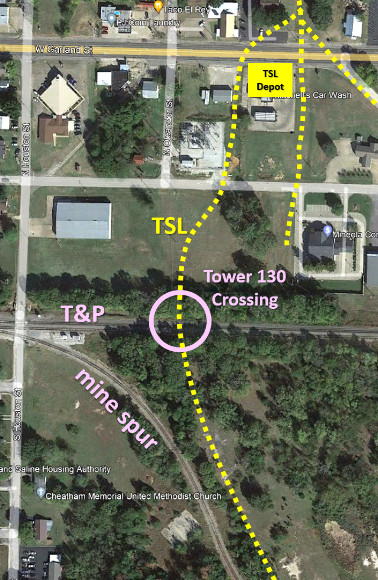

Above Left: This map shows the

railroads near Grand Saline. Among all of these tracks, only the T&P tracks have

fully survived. Above Center:

The TSL depot was located on the west side of the tracks immediately south of

the Garland St. grade crossing. The TSL tracks merged into the existing mine

spur just off the bottom of the map, which is also where the line to Van

continued to the south. Above Right:

The mine spur terminates at the Morton Salt mine located about a mile south of

the UP main line on the east side of Grand Saline. The white landscape is the

vast salt beds that have reached the surface.

Above: These two 2022 Google Street Views from Garland

St. look north (left) and

south (right) where the TSL

tracks from Alba entered Grand Saline. The water tower sits in the swale of the

TSL line to Alba which narrowed from multiple yard tracks into a single track

going north. South of Garland St., the TSL depot sat where the car wash is

currently located to the right. The

mine spur lead passed along the west side of the depot while yard tracks were

located on the east side. Behind the sign to the left and stretching all

the way back to the buildings in the far distance was a rectangular salt

warehouse that sat at an angle served by both the TSL and the T&P. This had

originally been an evaporation plant of the B. W. Carrington salt works.

Above Left: T&P depot at Grand

Saline in 1912 (Grand Saline library collection) This was presumably the station

built to replace the initial 1872 depot. Above

Right: This is the "final" T&P depot at Grand Saline.

In the 1980s, the depot was repurposed to house the

Grand Saline Public Library. (Richie

Morgan photo, 2016)

Later in 1929, oil was

discovered near Van, a community located eleven miles southeast of Grand Saline.

The T&P tracks at Grand Saline were reasonably close to Van, but the

International & Great Northern line between Mineola and Lindale was a similar

distance northeast of Van. To get there first, the T&P funded the TSL to build 11.5

miles of tracks south from Grand Saline to Van.

Later in 1929, oil was

discovered near Van, a community located eleven miles southeast of Grand Saline.

The T&P tracks at Grand Saline were reasonably close to Van, but the

International & Great Northern line between Mineola and Lindale was a similar

distance northeast of Van. To get there first, the T&P funded the TSL to build 11.5

miles of tracks south from Grand Saline to Van.